Abstract

Background

This study aimed to understand how respondents from three Asian countries interpret and perceive the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS).

Method

Data were from a project that aimed to examine the cultural appropriateness of EQ-5D in Asia. Members of the general public from China, Japan, and Singapore were interviewed one-to-one in their preferred languages. Open-ended questions (e.g. What does “best imaginable health” mean to you?) were used to elicit participants’ interpretation of the labels of EQ-VAS. How the scale could be improved was also probed. Thematic and content analyses were performed separately for each country before pooling for comparison.

Results

Sixty Chinese, 24 Japanese, and 60 Singaporeans were interviewed. Interpretations of the label “Best Imaginable Health” varied among the participants. Interestingly, some participants indicated that “Best Imaginable Health” is unachievable. Interpretations for “Worst Imaginable Health” also varied, with participants referring primarily to one of three themes, namely, “death,” “disease,” and “disability.” There were different opinions as to what changes in health would correspond to a 5- to 10-point change on the EQ-VAS. While participants opined that EQ-VAS is easy to understand, some criticized it for being too granular and that scale labels are open to interpretation. Findings from the three countries were similar.

Conclusion

It appears that interpretations of the EQ-VAS vary across Asian respondents. Future studies should investigate whether the variations are associated with any respondent characteristics and whether the EQ-VAS could be modified to achieve better respondent acceptance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Asian respondents appear to understand the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS), but interpret it quite differently. |

The inter-respondent variations in interpretation of the EQ-VAS warrant further investigations. |

The EQ-VAS might be easier to use if it is less granular. |

1 Introduction

Though originally developed for use in Europe, the EQ-5D questionnaire [1] is currently used worldwide not only to describe and value health, but also to inform important policy decisions based on economic evaluations. EQ-5D is a generic, self-complete questionnaire comprising two parts. The first part is the EQ-5D descriptive system (DS), which asks respondents to describe their health in five dimensions (Mobility, Self-Care, Usual Activities, Pain/Discomfort, and Anxiety/Depression) using either three or five problem levels (EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L, respectively). A utility/index score can be generated using the responses to the DS to indicate the value of the described health state [1]. The second part of the EQ-5D questionnaire is the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS), a 20-cm long vertical visual analog scale. The EQ-VAS contains a five-line instruction for respondents to rate their health on the day of the survey using a vertical, thermometer-like scale marked from “0” to “100,” with “100” labeled as “Best Imaginable Health” and “0” labeled as “Worst Imaginable Health.”

The EQ-VAS is conceptually different from the EQ-5D DS, which measures health using a common set of dimensions and which allows for the calculation of an index score based on the general public’s health preferences. The EQ-VAS, on the other hand, seeks the respondent’s overall rating of their current health. The EuroQol Group recommends that both parts of the questionnaire should be administered [2].

The EQ-VAS was originally developed for use in Europe by a group of European researchers, and its suitability for use in other cultures has not been widely assessed. A recent systematic review found mixed evidence on the validity of EQ-VAS in five of ten Asian countries [3]. However, no study to date has investigated how Asian respondents interpret the EQ-VAS, how they use it to rate their own health, or whether they consider it an appropriate method for such assessment. The current study, which is part of a larger project aimed to examine the cultural appropriateness of the EQ-5D questionnaire in Asia, aimed to address this knowledge gap. Qualitative methods were employed to answer the following research questions: How do Asians use the EQ-VAS scale? How do they interpret the scale elements of EQ-VAS? How do they perceive a change in scores on the EQ-VAS? Are there differences in interpretations and use of the VAS across Asian populations?

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

The interviews were first conducted in Singapore, then simultaneously in China and Japan. All participants had to (1) be a native who has lived in the country for the past 5 years, (2) be able to converse in the local language, (3) not be a family member of a recruited participant, and (4) be willing to take part in the study and be audio recorded. A common set of quotas were set to ensure a heterogeneous sample in terms of gender, educational level, and experience with illness. Depending on the demographics in each country, additional quotas were applied. For example, in China, where there is a huge distinction between rural and urban areas, an additional quota was applied based on residence location. In Singapore, which is a very multi-ethnic country, an additional quota for ethnicity was applied.

In China, participants over 18 years old were recruited via convenience sampling from six different cities, namely, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Jinan, Harbin, and Guiyang. In Japan, participants between 20 and 69 years of age from Tokyo, Chiba, Saitama, and Kanagawa Prefecture were invited to take part in the study. These participants were members of a panel maintained by a commercial survey company. In Singapore, Chinese, Malay, and Indian participants over 40 years old were recruited from the general public using convenience sampling methods.

The interviews were first conducted in Singapore, followed by China and Japan. The original age criterion was set at 40 because the study team believed that, compared to this group of participants, younger participants might not have had as much experience with poor health or as much opportunity to reflect upon the concept of health. For that reason, the older age group was thought more likely to make a richer contribution when discussing the concept of health. However, after data collection in Singapore, the team members decided to lower the age limit for China and Japan in order to achieve a more heterogeneous sample. Based on the age of legal adulthood, the lower age limit for China and Japan samples was reduced to 18 and 20 years, respectively. Due to the high cost of performing face-to-face interviews in Japan, the sample size was strictly determined by data saturation. Data saturation was deemed achieved when no new themes and information emerged from the last five transcripts. Given the geographical and ethnic diversity in China and Singapore, respectively, the sample sizes for those countries were based on quotas as well as data saturation.

2.2 Data Collection

Consenting participants were interviewed face-to-face and one-on-one by a trained interviewer in quiet areas such as participants’ homes or a meeting room. All interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder. Participants’ demographic characteristics were also collected.

A standard semi-structured interview guide was designed by the investigators to elicit participants’ understanding and conceptualization of health in general before exploring their perceptions of the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. The interview consisted of three main sections: (1) broad, open-ended questions were used to elicit the health concepts important to the participants; (2) participants were tasked to complete the EQ-5D DS, provide their opinions on the adequacy of the DS, and suggest how it could be improved to make it more relevant and adequate for them; and (3) participants were asked to complete the EQ-VAS independently and were then questioned on how they used the scale (Did you consider choosing a number that was not a multiple of 5?) and their interpretations of the labels and numbers on the EQ-VAS scale (What does “100” or “the best health you can imagine” mean to you? Do you think you can achieve “100” in the future? Did you achieve “100” in the past? What does “0” or “the worst imaginable health” mean to you?). Participants were also invited to share how they valued a change in health score of 5–10 points (What would a 5- to 10-point increase from 80 points represent? What type of change in health status would lead to a 5- to 10-point drop in score?). Suggestions for how the EQ-VAS can be improved were also probed for. “Anything else?” and “Why?” were used to prompt respondents. This paper presents the results from the third section of the interview.

2.3 Data Analysis

Data for interpreting the labels “Best Imaginable Health” and “Worst Imaginable Health” were analyzed using thematic analysis [4, 5]. Thematic analysis allows for the derivation of the dimensions and domains participants used to interpret the labels [4, 5]. All coders coded the transcript line by line. Focused coding was then conducted, where the common initial codes were grouped together into themes. After which, axial coding was used to organize the themes into domains. To ensure consistency between the coders, a codebook was developed for each country. The codebook comprised five fields (code, title, definition, example, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and relationship to other codes). The definitions of the labels used were based on participants’ interpretation. Content analysis [4] was used to analyze the remaining data. The main difference between thematic and content analysis is that the latter allows for quantification of the data [4]. Data from the three countries were analyzed separately before being pooled for comparison.

All interviews from China were transcribed and analyzed in the native language (Mandarin) by two research assistants from China before being translated to English. In the case where the two coders could not reach consensus, the principal investigator (NL) was consulted.

All interviews from Japan were transcribed in the native language (Japanese). The external survey company which conducted the interviews in Japan completed the open coding process. After the open codes were generated, the codes were translated into English. AI oversaw the translation process and made sure that no information was lost during translation. After which, the translated open codes were analyzed by a research assistant from Singapore.

Interviews in Singapore were either conducted in Mandarin or English. Interviews in Mandarin were transcribed and translated to English before analysis. The analysis was conducted by two research assistants from Singapore. In the case where the two coders could not reconcile differences, the principal investigator (NL) was consulted. One research assistant from Singapore pooled the data across the countries, following closely to the codebooks developed for each country for comparison.

Excerpts were used to support the analysis: prefixes C, J, and S were used to indicate participant’s country of origin (China, Japan, and Singapore). Where necessary, minor modifications were made to the excerpts for easy understanding, such as when colloquial language was used or when a sentence was incomplete.

3 Results

3.1 Demographics

Sixty native Chinese were interviewed. Among those, 29 were male. The mean age was 48.2 (range 20–80) years. A majority of participants had either directly recieved or provided care (66.7%), were married (80%), and had at least a university degree (50%) (Table 1). A majority of participants lived in an urban location in China (75%) (data not shown).

Twenty-four native Japanese were recruited and interviewed, of which 12 were male. The mean age was 46.3 (range 27–68) years. A majority of participants did not have experience with receiving or giving care (79.2%). Most participants had completed secondary education (66.7%), and were married (70.8%) (Table 1).

Sixty native Singaporeans, comprising 20 Chinese, 20 Malays, and 20 Indians, were recruited and interviewed. Of the 60 participants, 28 were male, and the mean age was 58.9 (range 40–88) years. Most of the participants had either received or provided care for others (73.3%) (see Table 1). A total of six interviews were conducted in Mandarin, and the remainder were conducted in English. Since the initial analysis suggested insufficient differences between the three ethnicities to warrant being presented separately, they have been combined for presentation in this paper.

3.2 Using the EQ-VAS Scale

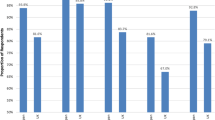

All participants from Japan (n = 24) and almost all participants from China (n = 56) and Singapore (n = 58) chose a VAS score that was a multiple of 5 to rate their health on the day of the interview. Reasons given were that it was cognitively too challenging to express health to the degree of precision represented by the hash marks on the VAS, which signify a difference of one point; that there is no difference between scores with a difference of less than 5 points; and that participants chose points on the scale that had a number printed next to them. Table 2 shows the reasons participants gave for choosing multiples of 5 to rate their health, with the corresponding example quotes.

3.3 Interpretation of the Label “Best Imaginable Health” or “100”

Participants’ interpretations of “100” were classified into five themes, namely, physical health, mental well-being, social relationships, medical conditions and treatment, and health promotion knowledge and behaviors. Table 3 shows the domains and themes used by participants to interpret “100,” with corresponding example quotes. Except for social relationships, all themes were mentioned by participants from all three countries. The Japanese participants were the only ones not to describe “100” in terms of social relationships. Participants most frequently described “100” as a combination of different themes, and differences in the combinations were apparent between and within countries. Table 4 shows the top 5 combinations of themes participants used to interpret “Best Imaginable Health,” with supporting quotes.

3.4 Achievability of “Best Imaginable Health” or “100” on EQ-VAS

All Japanese and almost all Chinese (91.6%) and Singaporeans (91.6%) did not rate themselves at “100” on the VAS. Reasons given included feeling fatigued, a lack of sleep, feelings of stress or pain and discomfort, and having an existing medical condition (Table 5). A majority of Chinese (63.3%), Japanese (54.2%), and Singaporean (56.7%) participants considered that they would have assigned themselves a score of “100” in the past, for example, because they were younger, able to do more things, not diagnosed with any medical condition, and were experiencing less stress (Table 5). A majority of Chinese (66.7%), Japanese (54.2%), and Singaporean (68.3%) participants believed that they would not rate themselves at “100” in the future, for example, because of physical deterioration due to aging and the increased likelihood of being diagnosed with a medical condition. A minority of participants in each country (15% in China, 4.2% in Japan, and 23.3% in Singapore) believed that “100” is impossible to attain for a human being. Supporting quotes can be found in Table 5.

3.5 Interpretation of the Label “Worst Imaginable Health” or “0”

The interpretation for “Worst Imaginable Health” was also diverse. Responses from participants can be grouped into three themes. Table 6 summarizes the themes used by participants when interpreting “0,” with corresponding participant quotes. Firstly, the concept of death. It is related to states such as “near-death,” “being dead,” or “the stage when they felt dying rather than living.” The second theme, disease, marked the presence of a serious illness or advanced chronic diseases, such as advanced cancer or an advanced stage of dementia. The third theme concerned various degrees of disability, whereby participants reported that being unable to walk, being wheelchair-bound, or being paralyzed or bedridden would represent being at “0” on the EQ-VAS.

3.6 Change in Health State Corresponding to a 5- to 10-Point Change on the EQ-VAS

Opinions varied as to what change in health would correspond to a 5- to 10-point change on the EQ-VAS. Responses from participants could be grouped into five domains, namely, physical health, mental well-being, social relationship, medical conditions and treatment, and health promotion knowledge and behaviors. Table 7 shows the summary of health domains participants mentioned, if affected, would correspond to a 5- to 10-point change on the EQ-VAS, together with supporting participant quotes.

Notably, some participants from Japan and Singapore felt that a 5-point change on the VAS would not be particularly significant. Supporting quotes can be found in Table 7.

3.7 Comments and Suggestions to Improve the EQ-VAS

Participants who considered EQ-VAS to be a good scale indicated that they found the VAS easy to understand. EQ-VAS was also thought to be a tool for getting people to reflect on their health. A few participants also mentioned having a scale high in granularity as a positive aspect. Corresponding quotes can be found in Table 8.

The most frequent negative comments about EQ-VAS across the three countries were that the scale is too granular and that the scale labels and number points were vague and open to interpretation. To address these negative aspects, participants suggested using a shorter scale and introducing explanatory word labels or examples to the scale number points. Other negative comments included that it is difficult to summarize a complex concept such as health into one number, and that the instructions on the EQ-VAS are too long. One Singaporean and one Chinese participant were not able to complete the EQ-VAS. Corresponding quotes can be found in Table 8.

One participant from Japan commented that it would be easier to read the scale if it was oriented horizontally (Table 8).

4 Discussion

As part of the EQ-5D questionnaire, the EQ-VAS has been widely used in Asian populations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate respondent perceptions of the scale in depth in Asia. Generally, there are similarities across the countries in how respondents interpret and use the EQ-VAS. Interestingly, there were considerable inter-respondent variations in the way participants interpreted labels and scores on the VAS. Furthermore, some respondents believed that “100” is never attainable, while some respondents believed that “0” corresponds to being dead, suggesting that the two anchor scores will never be utilized by them. The study also revealed individual differences within each country in terms of the achievability of “100” over time.

Varied or mistaken interpretations of VAS labels were also observed in previous studies [6,7,8]. For example, an early study revealed that there were differences in interpretation as to what “Best Imaginable Health” and “Worst Imaginable health” meant to different researchers [7]; another study revealed that some college students misinterpreted “Best Imaginable” as how easily the health state could be imagined [8]. Inter-respondent differences in interpretations could invalidate the comparability of the EQ-VAS scores across groups of respondents if the differences are associated with certain respondent characteristics. Different scores could be chosen by respondents in identical health status if their interpretations of “Best Imaginable Health” are different. For example, if a lot more Singaporeans than Japanese think “Best Imaginable Health” is not achievable, one would expect the EQ-VAS scores of Singaporeans to be lower than those of Japanese when other things are equal. Hence, systematic difference in scale interpretation might be responsible for the mixed evidence on the known-groups construct validity of EQ-VAS in Asia [3]. For example, EQ-VAS scores did not differ as expected between different severity groups of diabetic patients in Singapore [9] and Brunei [10]. Therefore, future studies should investigate whether interpretations of the EQ-VAS are associated with any respondent characteristics in Asian populations.

It should be noted that this variability is unlikely to affect the intra-rater reliability (e.g., test-retest reliability) or responsiveness of the EQ-VAS. This is because, as long as an individual has his or her own way of interpreting the EQ-VAS, the interpretation is unlikely to change over a short period of time. This might explain why the EQ-VAS is found to have good reliability and responsiveness in Asia [3]. Those two measurement properties were assessed in terms of the within-individual change in the EQ-VAS scores. This means that, although the construct measured by EQ-VAS may differ across respondents, this difference does not affect the ability of the scale to capture change in the measured health construct that occurs to respondents or groups of respondents.

In this study, we found that the 1-point increment on the EQ-VAS scale was not particularly significant to respondents. While a few respondents also saw the 5-point increment on the EQ-VAS as trivial, most respondents were able to explain a change in health state that corresponds to a 5- to 10-point change on the EQ-VAS. This is consistent with existing literature that found the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) [11] of EQ-VAS to be around 8 [12,13,14].

Although the majority of the studied respondents had a positive opinion of the VAS and found it relatively easy to understand and respond to, some potential issues surfaced. For example, respondents tended to only use values that are multiples of 5 on the VAS to rate their health, which may limit the instrument’s precision. Some respondents also considered that EQ-VAS was not easy to respond to, though only two respondents failed to complete it. The two respondents who failed to complete the EQ-VAS had difficulty summarizing health into a single number. This suggests that the EQ-VAS might represent a cognitive challenge to some respondents, a finding which echoes results from an earlier UK study [15].

One suggestion from our respondents might be useful for improving the design of EQ-VAS, should there be such a need in the future. Based on our findings, the hash-mark lines that represent an increment of 1-point could be removed to simplify the task for respondents. Should such a modification be made, research will need to be done to verify if the benefits of doing so outweigh any inconvenience to respondents who prefer to use the hash-marks to pinpoint their scores. More research is also warranted to verify if the benefits of such changes will also apply to respondents from other countries.

There are a few limitations to this study. Firstly, unlike the sample from China and Japan, the Singaporean sample only included participants who were aged 40 years old and above. Since the younger generation might have different views, the data reflected in this study might not be comprehensive. However, an argument in favor of this older sample is that, compared to the younger generation, the older generation has a higher likelihood of experiencing poor health, and is, therefore, able to contribute more during the cognitive interview. Secondly, the analysis of the Japanese data was conducted by two Singaporeans. Therefore, there might be a possibility of losing nuances during translation. However, this is highly unlikely as AI ensured coding quality.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides new information on how respondents from China, Japan, and Singapore interpret and perceive the EQ-VAS. Given the variation in interpretations among respondents, future studies should investigate whether the variations could be a threat to the comparability of the EQ-VAS scores in group comparisons. Results of this study might be used to tweak the EQ-VAS in order to improve its respondent acceptance.

References

Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol group: past, present and future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127–37.

EQ-5D-5L User Guide. 2019. https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/. Accessed 29 May 2020.

Qian X. Tan RL-Y, Chuang L-H, Luo N. Measurement properties of commonly used generic preference-based measures in East and South-East Asia: a systematic review. PharmacoEconomics. 2020;38:159–70.

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Torrance GW, Feeny D, Furlong W. Visual analog scales: do they have a role in the measurement of preferences for health states?. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Sage CA; 2001.

Fox-Rushby J, Selai C. What concepts does the EQ-5D measure? Intentions and interpretations. In: Brooks R, editor. The measurement and valuation of health status using EQ-5D: a European perspective. Dordrecht: Springer; 2003. p. 167–82.

Busschbach J, Hessing D, de Charro F. Observations on one hundred students filling in the EuroQol questionnaire. In: Kind P, editor. EQ-5D concepts and methods: a developmental history. Dordrecht: Springer; 2005. p. 81–90.

Luo N, Cang S-Q, Quah H-MJ, How C-H, Tay EG. The discriminative power of the EuroQol visual analog scale is sensitive to survey language in Singapore. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):32.

Koh D, Bin Abdullah AMK, Wang P, Lin N, Luo N. Validation of Brunei’s Malay EQ-5D questionnaire in patients with type 2 diabetes. PloS One. 2016;11(11):e0165555.

Jaeschke R, Guyatt G, Keller J, Singer J. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the meaning of a change in quality-of-life questionnaire score. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:407–15.

Luo N, Chew L-H, Fong K-Y, Koh D-R, Ng S-C, Yoon K-H, et al. Do English and Chinese EQ-5D versions demonstrate measurement equivalence? An exploratory study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):7.

Chen P, Lin K-C, Liing R-J, Wu C-Y, Chen C-L, Chang K-C. Validity, responsiveness, and minimal clinically important difference of EQ-5D-5L in stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(6):1585–96.

Zanini A, Aiello M, Adamo D, Casale S, Cherubino F, Della Patrona S, et al. Estimation of minimal clinically important difference in EQ-5D visual analog scale score after pulmonary rehabilitation in subjects with COPD. Respir Care. 2015;60(1):88–95.

Devlin NJ, Hansen P, Selai C. Understanding health state valuations: a qualitative analysis of respondents' comments. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(7):1265–77.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the EuroQol Group (EQ Project 2016290) and the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) Seed Fund from the National University of Singapore (1/2019).

Conflict of interest

Nan Luo, Michael Herdman, Zhihao Yang and Ataru Igarshi are members of the Euroqol Group. Rachel Lee-Yin Tan declare no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (NUS-IRB Ref No.: S-19-129E and B-16-252) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies.

Consent for publication

As part of informed consent for the study, participants gave consent for publication of the data derived from their participation in the research study.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

NA.

Author contributions

NL and MH contributed to the study conception and design. AI and ZY collected the data in Japan and China respectively. RL-YT consolidated and analyzed the data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RL-YT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, R.LY., Yang, Z., Igarashi, A. et al. How Do Respondents Interpret and View the EQ-VAS? A Qualitative Study of Three Asian Populations. Patient 14, 283–293 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00452-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00452-5