Abstract

Patient-oriented research is a process whereby patients or caregivers are included as research partners so that research focusses on topics that are priorities and lead to findings that translate into practice. Using a case study of preferences for stem cell transplant in scleroderma, we report on a patient-oriented research approach to developing a discrete choice experiment. Our patient-oriented research application followed the four guiding principles in Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research: inclusiveness, support, mutual respect and co-build. In this case study, patient partners were involved at different levels of engagement to match individual availability, skillset and roles in the team. They advised, to different degrees, on all aspects of the study from design to analyses. Using a patient-oriented research approach led to the inclusion of attributes that would likely have been excluded (e.g. support from a multidisciplinary team), and realistic framing of patient-relevant and sometimes sensitive attributes (e.g. mortality and cost). Meeting locations and times were adjusted to accommodate all-team circumstances. Institutional constraints on the reimbursement for patient partners influenced the timing and extent of involvement. We found that adopting a patient-oriented research approach to discrete choice experiment design injected unique knowledge and expertise into the team, improved the representativeness of the sample recruited, minimised researcher biases, and ensured appropriate attribute selection and descriptions. The patient-oriented research approach highlighted some constraints of discrete choice experiment designs and, while not a solution, might ensure the methodological trade-offs remain patient relevant. Institutional challenges must be addressed to progress patient-oriented health economics research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Using a patient-oriented approach to develop a discrete choice experience might contribute to greater transparency, acceptability and appropriateness of the methods, and increase participation in research. |

Researchers looking to integrate patient partners in their research team need to consider that patients often join teams while keeping their full-time jobs, responsibilities and social commitments; accommodations must be made that allow inclusiveness and avoid burnout. |

Institutional challenges need to be confronted to enhance how patient partners can contribute to research projects at their full potential. Involving patient partners can help to identify and highlight methodological shortcomings of research designs. |

1 Introduction

Patient-oriented research (POR) is “a continuum of research that engages patients as partners, focusses on patient-identified priorities and improves patient outcomes” [1]. In the last decade, POR became the gold standard in clinical research and permeated adjacent fields, including health economics. The approach moves away from the traditional paradigms where the patient is the object of the research, to a model in which the patient’s experience is seen as valuable to the co-creation of knowledge. Patient partnership in research is therefore distinct from patient participation in research. Through POR, patients are involved as team members to contribute to the study’s design, not as research participants who provide data used to answer a research question. Patient-oriented research constitutes a significant paradigm change motivated by a recognition that moving away from paternalistic research models is ethically, politically and socially sound, particularly in publicly funded research [2]. Patient-oriented research can lead to better alignment between research designs and patient preferences, which can increase research participation, uptake and impact [1].

Using POR might also contribute to reduced waste in research. Recent estimates suggest that 85% of research funding is wasted as a result of poor reporting of results, inefficient prioritisation of research funding, poor design, conduct, and analysis, and lack of knowledge translation [3,4,5]. For example, studies that used discrete choice experiments (DCEs) to predict uptake of new rheumatoid arthritis preventative treatments suggest that few drugs being studied would be acceptable [6, 7]. These studies were conducted after the trials were completed, and large investments made. If a POR approach is used prior to clinical trials, research funds might be channelled to studying treatments that are most likely to be preferred by the people they are intended for, which would in turn lead to improved outcomes.

Discrete choice experiments are a type of survey that allows researchers to elicit stated preferences for goods or services [8]. In healthcare, DCEs are particularly useful to create hypothetical markets of health technologies that are not yet available, allowing understanding of peoples’ preferences and the trade-offs they are willing to make when considering, for example, a new treatment. One of the main challenges of stated preferences methods is the potential disconnect between stated and revealed (actual) preferences, known as hypothetical bias [9]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of DCEs concluded that DCEs generate reasonable predictions of health-related behaviors [10].

Following methodological guidelines for DCE development can help minimise hypothetical bias [11]. Development of DCEs requires thorough understanding of the decision problem being simulated, achieved through literature reviews, stakeholder consultation and qualitative research [8, 12]. Poor design and complexity can result in inexplicable choices, hindering the analysis or interpretation of the results [13]. It is recommended that researchers pay careful attention to and adequately report the many stages of survey development, including choosing the alternatives, identifying attributes and levels, and deciding on how each component is described and worded [14]. This process offers many early opportunities for patient involvement, which can lead to higher levels of engagement throughout the remainder of the study.

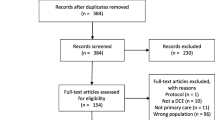

In Canada, POR is now a requirement for obtaining health research funding, and it is therefore likely that more researchers, including health economists, will seek to engage patients more in their projects. This article contributes to increased transparency and harmonisation in POR by reporting on its application to the development of a DCE using a case study where we elicited the preferences of people with scleroderma for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (AHSCT) [Box 1].

3 Approach

Based on the four guiding principles for integrating patient engagement into research—inclusiveness, support, mutual respect and co-build—established by The Patient Engagement Framework [1], we report on how we applied a POR approach to develop a DCE.

3.1 Inclusiveness

“Patient engagement in research integrates a diversity of patient perspectives and research is reflective of their contribution – i.e., patients are bringing their lives into this.” [1]

We recruited two patient partners, TB and JB, to our team that also included clinical experts, health economists, health systems researchers and knowledge translation specialists. Patient partners’ roles in the team were discussed and defined according to their availability to commit, experience, interest in being part of a research study and health. TB and JB contributed lived experienced with scleroderma, knowledge of the patient community, and clinical environment in British Columbia, and experience in participating in discussion groups with stakeholders, including patients. The research team met regularly to make decisions as the project progressed, including decisions about planning of research activities such as recruitment, informational materials, survey development, survey administration, data collection, interpretation and knowledge translation.

3.2 Support

“Adequate support and flexibility are provided to patient participants to ensure that they can contribute fully to discussions and decisions. This implies creating safe environments that promote honest interactions, cultural competence, training, and education. Support also implies financial compensation for their involvement.” [1]

Initial meetings with the patient partners covered the environment the project was set in, and what sort of accommodations could be made to help the patient partners feel integrated. Patient partners were asked to record the number of hours they dedicated to the study and were reimbursed for their time. Time was dedicated to communicate methodological concepts and share materials so that equal participation in methodological decisions could be achieved. Opportunities were identified for patients to participate in talks and conferences.

3.3 Mutual Respect

“Researchers, practitioners and patients acknowledge and value each other’s expertise and experiential knowledge.” [1]

The study was developed by a multidisciplinary team in recognition that each party would bring valuable skills and knowledge to the project. Early meetings were set up for the members to familiarise with each other’s background, skills and experiences. An open dialogue about needs and expectations was kept throughout the project. A practical example of mutual respect was the effort to, whenever possible, send materials to the patient partners and allowing time to review and contribute to consequent decisions, even if this meant readjusting timelines. Decisions were made as a team, and methodological choices discussed and negotiated. It was suggested that the patient partners kept a log about their experience for separate reporting in conferences, journals and policy communications; a patient partner reflection was submitted as a commentary to this issue [15].

3.4 Co-build

“Patients, researchers and practitioners work together from the beginning to identify problems and gaps, set priorities for research and work together to produce and implement solutions.” [1]

The idea for this project was conceived by TB (patient partner) and MHa (health economist) through a conversation at a meeting on AHSCT in Montreal 2018. A research proposal was jointly prepared and subsequently funded by the Health Economics and Decision Modelling cluster of the British Columbia Support Unit [16]. The patient partners were involved in methodological decisions, data collection, interpretation, attribute selection and survey design. Following existing classification for the level of engagement [17] we aimed, in the least, to engage the patient partners at the ‘Collaborate’ level.

4 Application

A summary of how the POR approach was implemented in the different stages of the research project is presented in Table 1.

4.1 Inclusiveness

We achieved different levels of engagement with each patient partner and at different stages of the project (Table 1). TB was involved at a collaborative level and JB at a consultative level. We worked with our patient partners to achieve a manageable level of engagement that they felt comfortable with. Flexibility to accept the level of engagement each party could offer was important.

4.2 Support

In recognition of the patient partners’ commitments (full-time jobs, volunteering work and managing their health), the team sought to accommodate their schedules and minimise travelling. Team meetings were held outside working hours and off-campus, with the option to join in via a phone call, especially as JB was not local to the team. Patient partners were supported to independently communicate their experience in this project. TB presented her experience at the International Shared Decision Making conference (2019), participated in local events such as the Health Economics and Simulation Modelling academic half-day and contributed with a commentary on her experience of working with us on this project to accompany this paper in the special issue [15]. Reimbursement for time spent at these events was offered, in recognition that participation at conferences required use of vacation time, as well as usual expenses.

4.3 Mutual Respect

Mutual respect was a goal throughout the project and resulted in recognition of the value of each team member’s perspective. Patient partners’ views were considered in decisions and incorporated whenever possible. Mutual respect was fundamental for decisions where compromises had to be made to assure methodological feasibility. For example, patient partners felt that chemotherapy was an important attribute in itself and should be separated from the description of other possible complications. Such input was considered and several iterations of the attribute list were proposed until patients agreed with the final set. Complications of AHSCT were ultimately described using two attributes, one for short-term complications including death from the treatment and the other for long-term complications including cancer. These trade-offs between methodological limitations and patient preferences were discussed to ensure that they were not seen as a devaluation of the patients’ contribution.

4.4 Co-build

TB was involved in the research project from the beginning, including the pre-funding stages of formulating the research question and writing the grant proposal. TB was also involved in preparing the focus groups material, facilitating the focus group, data interpretation and identification of attributes. From the beginning, TB highlighted the value of recruiting a second patient partner with a different lived experience, and supported the team in establishing contact with JB, our second patient partner. JB joined in time to participate in the focus group via a conference call, as an observer, and provided consulting on focus groups materials, data interpretation, identification of attributes and levels, survey design and piloting.

Patient partner involvement with the design of the formative qualitative data collection stage was decisive to the direction the project took (Table 1). They recognised that our design for focus groups, to be conducted in person in Vancouver, would exclude the perspectives of those living in rural and remote areas. Furthermore, these participants would likely have different perspectives and factors influencing their decision making. We therefore enabled participants living outside the metro Vancouver area to participate via a conference call. TB took the role of a co-facilitator in the focus group, which aimed to ease power dynamics, build trust, and assist in translating concepts between the researchers and focus group participants. JB’s participation as an observer in the focus group proved helpful for debriefing and interpretation of the results.

The patient partners had a central role in attribute selection and on how attributes should be worded and the choices framed (Table 1). For example, they were helpful in wording sensitive attributes for patients, such as mortality and chemotherapy-associated risks, which researchers were uncomfortable with. Patient partners stressed the importance of including non-clinical attributes, such as ‘support from multidisciplinary team’ and the ‘distance of the treatment from your home’, which were also ranked as important by focus groups participants. Following the patient partners’ interest in using the survey to share evidence-based information about AHSCT, we added a set of pre-DCE questions providing information about this novel treatment and testing the respondents’ knowledge about the information given. This was a way to share evidence, provide context for the attributes and levels, and test respondents’ understanding of those attributes before they started the DCE.

5 Discussion

In this article, we report on the application of a POR approach to developing a DCE following the patient engagement framework [1]. Overall, we found that this approach brought value to the research project. In line with suggestions for POR initiatives, we were able to formulate a research question that aligned with patients’ priorities and conducted the work in recognition of the patients’ values, which resulted in a rewarding experience for the team. Having patients as members of the research team increased the perceived trustworthiness of the project to participants, which helped with recruitment and dissemination, as reported elsewhere [19]. A POR approach also created a more reflective and critical atmosphere regarding research, knowledge and power within the study team, which likely would not have been the case without the inclusion of patient partners.

The patient partners were engaged at two different levels: collaboration (TB) and consultation (JB). It seems important that those involved in POR, including researchers, supporters and funding agencies, accept that more engagement is not necessarily better [20] and not to preclude potential patient partners from getting involved solely to achieve the highest level of engagement. As tools to evaluate POR and its impact become available [21, 22], consideration must be given to the expected impact of different engagement levels.

This team corroborates other researchers’ experiences that POR can be time and resource intensive [23, 24]. Inclusiveness meant recognising that patient partners are active members of society with ongoing commitments including full-time jobs, volunteer work, caring responsibilities and their health condition. Project planning and budget estimations must accommodate these, as well as patient partners’ training, support for travelling, flexibility in scheduling meetings and other activities.

We also found that POR approaches might collide with principles of research governance. Engagement with patient partners ideally starts as early as possible, before funding applications are submitted, to allow, for example, for the co-formulation of the research questions and study design. This means that patients are asked to contribute long before the project is funded and approved by an ethics committee board, i.e. they are involved for a longer period than that of the project’s timeline. During this time, researchers might not have a way of compensating patients for their time and expertise. Given that not all projects are successful in funding competitions, patient partners are at risk of becoming professionally, financially and emotionally invested in projects that might not be taken forward.

There were some challenges in articulating a POR approach within a DCE study. For example, patient partners would have preferred that more attributes were included while also voicing concerns that the survey itself was too long [12 choice sets in total, and completion time of around 30 min]. The patient partners were also concerned that the hypothetical treatment options might be misinterpreted as actual options. Many of these issues are known methodological challenges for DCEs. For instance, Coast et al. describe tensions in developing DCEs, particularly in narrowing down rich qualitative data into a finite manageable number of attributes [12]. The number of attributes to include in a DCE is contended, with recommendations to limit attributes to assure cognitive feasibility and statistical efficiency, but including all relevant attributes to limit omitted attribute bias [8, 25, 26]. Though research in this latter area exists, an ideal number has never been suggested. Thus, researchers tend to deal with this issue on a case-by-case basis. Explaining and justifying the methods to the patient partners was a critical step because it built trust and a common ground of understanding to promote everyone’s participation in such methodological decisions. While we were not able to accommodate some of the patients’ preferences, taking a POR approach ensured the omitted attributes were accounted for in the scenario descriptions, the chances of misinterpretation of the scenarios were minimised and the included attributes were the most relevant to patients.

Patient-oriented research can be met with resistance within the research community. One of the reasons might be that it can be wrongly perceived as a type of qualitative research, and its value measured using the same rigorous standards expected from qualitative research methods. Whilst qualitative research collects data to answer a research question following rigorous theoretical frameworks [27], POR aims to draw on patients’ expertise to guide key decisions about aspects of the research project. This explains why in a POR approach, it is neither possible nor the aim to guarantee representativeness and inclusion of diverse views. Another reason for resistance to POR might be that patients’ contributions to the direction of a project might be interpreted externally as advocacy. In Canada, training is available for patient partners that covers research governance, ethics and research methods. It needs to be recognised that in POR, patients should have the same status that any member of a multidisciplinary team would have. Therefore, the patients’ contrasting viewpoints, goals or opinions should not be viewed any differently than those of the health economist, the clinician or the statistician in the team.

Power imbalances are an inherent issue in POR and one that can reduce the level of patient involvement to a minimum if preventive measures are not in place [28]. Yet, academia is built on rooted power structures, notably power of knowledge, that conflict with POR’s endeavour to empower patients to influence research [29]. Patient partners often occupy a more vulnerable position than other team members. Strategies to involve patients in the research process and mitigate power imbalances rely on the researchers’ skills to dialogue, convene and communicate, as well as the creation of a safe environment [30]. Currently, the patient partner integration and compensation in Canada amounts to that of a volunteer position. With the requirement by many funding agencies to incorporate POR into project proposals, the opportunity and space for tokenism is inevitably created. Patient-oriented research guidelines and best practices are needed to ensure that POR is incorporated into research projects in ways that mitigate some of the issues we highlighted and to prevent POR from becoming another possible source of waste of valuable resources in the research process.

6 Conclusions and Future Directions

Patient-oriented research might be a way to overcome challenges that, for many years, researchers have struggled with: ensuring transparency, accountability, acceptability and appropriateness of the methods, increasing participation in research, taking diverse perspectives into account and reducing waste by increasing the uptake of research findings into practice. Applying a POR approach to the DCE design can embed a unique knowledge and expertise that may affect methodological choices and enhance the scope and meaningfulness of health economics research. In addition to evaluating the impact of POR on research outcomes, institutional challenges and some methodological shortcomings of DCE need to be confronted to move such a rewarding research paradigm forward.

References

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Strategy for patient‐oriented research: patient engagement framework. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2014.

Aubin D, Hebert M, Eurich D. The importance of measuring the impact of patient-oriented research. CMAJ. 2019;191(31):E860–E864864.

Virginia Minogue BW. Reducing waste in the NHS: an overview of the literature and challenges for the nursing profession. 2015. https://www.journals.rcni.com/nursing-management/reducing-waste-in-the-nhs-an-overview-of-the-literature-and-challenges-for-the-nursing-profession-nm.2016.e1515. Accessed 30 Jan 2020.

Minogue V, Wells B. Managing resources and reducing waste in healthcare settings. Nurs Stand. 2016;30(38):52–60.

Minogue V, Cooke M, Donskoy A-L, Vicary P, Wells B. Patient and public involvement in reducing health and care research waste. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;12(4):5.

Harrison M, Spooner L, Bansback N, Milbers K, Koehn C, Shojania K, et al. Preventing rheumatoid arthritis: preferences for and predicted uptake of preventive treatments among high risk individuals. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0216075.

Harrison M, Bansback N, Aguiar M, Koehn C, Shojania K, Finckh A, et al. Preferences for treatments to prevent rheumatoid arthritis in Canada and the influence of shared decision-making. Clin Rheumatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05072-w.

Reed Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Mühlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13.

Beck MJ, Fifer S, Rose JM. Can you ever be certain? Reducing hypothetical bias in stated choice experiments via respondent reported choice certainty. Transp Res Part B Methodol. 2016;89:149–67.

Quaife M, Terris-Prestholt F, Di Tanna GL, Vickerman P. How well do discrete choice experiments predict health choices? A systematic review and meta-analysis of external validity. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(8):1053–66.

Bridges J, Onukwugha E, Johnson F, Hauber A. Patient preference methods: a patient centered evaluation paradigm. ISPOR Connect. 2007;13(6):4–7.

Coast J, Al-Janabi H, Sutton EJ, Horrocks SA, Vosper AJ, Swancutt DR, et al. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012;21(6):730–41.

Vass C, Rigby D, Payne K. The role of qualitative research methods in discrete choice experiments. Med Decis Making. 2017;37(3):298–313.

Hollin IL, Craig BM, Coast J, Beusterien K, Vass C, DiSantostefano R, et al. Reporting formative qualitative research to support the development of quantitative preference study protocols and corresponding survey instruments: guidelines for authors and reviewers. Patient. 2020;13(1):121–36.

Burch T. Patient commentary: added value and validity to research outcomes through thoughtful multifaceted patient-oriented research. Patient. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00432-9.

BC SUPPORT Unit. Health economics and simulation modelling (HESM) methods cluster. https://bcsupportunit.ca/health-economics-simulation-modelling/. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

International Association for Public Participation. IAP2 spectrum of public participation. Toowong, Queensland: International Association of Public Participation Australasia; 2007.

Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health: a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Hannigan A. Public and patient involvement in quantitative health research: a statistical perspective. Health Expect. 2018;21(6):939–43.

Hahn DL, Hoffmann AE, Felzien M, LeMaster JW, Xu J, Fagnan LJ. Tokenism in patient engagement. Fam Pract. 2017;34(3):290–5.

Boivin A, Richards T, Forsythe L, Grégoire A, L’Espérance A, Abelson J, et al. Evaluating patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2018;6(363):k5147.

Boivin A, L’Espérance A, Gauvin F-P, Dumez V, Macaulay AC, Lehoux P, et al. Patient and public engagement in research and health system decision making: a systematic review of evaluation tools. Health Expect. 2018;21(6):1075–84.

Blackburn S, McLachlan S, Jowett S, Kinghorn P, Gill P, Higginbottom A, et al. The extent, quality and impact of patient and public involvement in primary care research: a mixed methods study. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4(1):16.

Kendall C, Fitzgerald M, Kang RS, Wong ST, Katz A, Fortin M, et al. “Still learning and evolving in our approaches”: patient and stakeholder engagement among Canadian community-based primary health care researchers. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;3(4):47.

Marshall D, Bridges JFP, Hauber B, Cameron R, Donnalley L, Fyie K, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health: how are studies being designed and reported? Patient. 2010;3(4):249–56.

Kløjgaard ME, Bech M, Søgaard R. Designing a stated choice experiment: the value of a qualitative process. J Choice Model. 2012;5(2):1–18.

Doria N, Condran B, Boulos L, Maillet DGC, Dowling L, Levy A. Sharpening the focus: differentiating between focus groups for patient engagement vs qualitative research. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4(1):19.

O’Shea A, Boaz AL, Chambers M. A hierarchy of power: the place of patient and public involvement in healthcare service development. Front Sociol. 2019;4. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00038/full. Accessed 26 Jan 2020.

Mourad RP. Social control and free inquiry: consequences of Foucault for the pursuit of knowledge in higher education. Br J Educ Stud. 2018;66(3):321–40.

Stern R, Green J. A seat at the table? A study of community participation in two Healthy Cities Projects. Crit Public Health. 2008;18(3):391–403.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the substantial contributions of Jennifer Beckett (referred to as JB throughout the manuscript) to the design and plan for acquisition of data, advice, and interpretation of pilot data through her role as patient partner on this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH, TB and TL conceived the idea for this study. NB was involved in further refinement of the research plan and provided guidance on using patient-oriented research to discrete choice experiments. SM provided expertise on patient-oriented research approaches to qualitative research and knowledge translation. MA and MH led the process of conducting all research activities. All co-authors supported the research activities’ design and implementation. MA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All co-authors reviewed, provided critical revisions for and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The preparation of this article was possible through the financial support from the BC SUPPORT Unit Health Economics and Simulation Modelling Methods Cluster, which is part of British Columbia’s Academic Health Science Network (Award number: HESM-001). The BC SUPPORT Unit receives funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Conflict of interest

Magda Aguiar is supported by a CIHR’s Health System Impact Postdoctoral Fellowship. Mark Harrison is supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award 2017 (#16813) and a Young Investigator Salary Award 2016 (until 2019) from The Arthritis Society (YIS-16-104). Mark Harrison held the UBC Professorship in Sustainable Health Care, which between 2014 and 2017 was funded by Amgen Canada, AstraZeneca Canada, Eli Lilly Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Canada, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada, Pfizer Canada, Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada), Hoffman-La Roche, LifeScan Canada and Lundbeck Canada. Sarah Munro is supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award in partnership with the Centre for Health Evaluation and Outcome Sciences 2019 (#18270). Tiasha Burch and Julia Kaal have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. Marie Hudson is funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé. Nick Bansback is co-lead of the Health Economics and Simulation Modelling Methods cluster, part of the BC SUPPORT Unit that commissioned this work as part of their mandate to explore and develop new methods for patient-oriented research. Tracey-Lea Laba is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Postdoctoral fellowship (APP1110230).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aguiar, M., Harrison, M., Munro, S. et al. Designing Discrete Choice Experiments Using a Patient-Oriented Approach. Patient 14, 389–397 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00431-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00431-w