Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between slower walking and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients.

Methods

We used North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis data to conduct a study of participants completing both the regular semiannual and supplemental spring 2010 surveys. Question 10 of the 12-item Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (“How much has your MS slowed down your walking?”) was used to assess patient-perceived impact of walking speed on HRQoL. HRQoL assessments included the Short Form-12 (SF-12), EuroQoL-5 Dimension (EQ-5D), Short Form-6 Dimension (SF-6D), and a visual analog scale (VAS).

Results

A total of 3,670 registrants completed both surveys and were included. Unadjusted analyses showed that compared with those classifying the impact of MS on walking speed as “not at all” (n = 661), participants stating MS impacted their walking speed “a little” (n = 722), “moderately” (n = 486), “quite a bit” (n = 714), and “extremely” (n = 1,087) reported poorer SF-12 physical component scale (PCS) (r = −0.69, p < 0.001), mental component scale (MCS) (r = −0.16, p < 0.001), and health status index scores (r = −0.50 to −0.51 for the EQ-VAS, EQ-5D and SF-6D, p < 0.001 for all). After adjustment for demographics and additional MS-related disability and symptoms, the impact of walking speed remained significant, although less profound for the PCS (reductions of 3.59–12.31 across walking speed classifications) and index scores (reductions ranging from 1.98 to 14.06, 0.04 to 0.13, and 0.02 to 0.07 for the EQ-VAS, EQ-5D, and SF-6D). Reduction in walking speed was no longer associated with a worse MCS (p > 0.05 all classifications of walking speed).

Conclusion

Incremental decrements in HRQoL were observed as patients perceived greater levels of reduction in their walking speed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

• The impact of walking speed on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed in a large multiple sclerosis (MS) population.

• Among respondents in this survey, incremental decrements in HRQoL, particularly that due to physical functioning, were observed as patients perceived greater levels of reduction in their walking speed.

1 Introduction

Impairment of mobility and walking are highly prevalent in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) [1–4]; however, it is important to note that they are not synonymous disabilities [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) draws a distinction between the two terms in their International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [1]. Walking is defined as foot-propelled locomotion, while mobility, a broader function, is defined as changes in body position or location. Walking is listed as a sub-classification of mobility.

Numerous studies have evaluated the effect of mobility impairment, as measured by the Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS), or general walking impairment on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with MS [1–4]. Studies have also looked at the association between walking speed and HRQoL in patients with MS, mainly using the Timed 25-foot Walk (T25FW) test as an objective, quantitative, functional measure of speed [6–11]. However, the impact of walking speed on HRQoL in patients with MS, as measured with a patient-reported outcome measure (PRO; defined as a measurement based on a report that comes directly from the patient about the status of a patient’s health condition, without interpretation by a clinician or anyone else) [12] is not known. Therefore, the objective of this analysis was to evaluate the association between walking speed assessed using a single 5-point Likert scale question included in the 12-Item Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (MSWS-12) [13] and HRQoL in a large population of North American MS patients.

2 Methods

We used de-identified data from the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) registry to conduct this study. NARCOMS gathers self-reported patient data on demographic factors (age, gender, annual household income), disease history (disease duration, occurrence of a relapse within the previous 6 months, use of a disease-modifying drug in the past 6 months), employment, MS-related symptoms and functional outcome measures (bladder/bowel, hand, vision, cognitive, sensory, spasticity, pain, fatigue, and mobility impairment) and quality of life through an extensive, regularly scheduled semiannual health survey of registrants. In 2010, NARCOMS, in conjunction with Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., began sending a semiannual supplemental questionnaire to NARCOMS regular survey respondents reporting a PDDS ≤7 to collect additional data on patient perceptions of walking, using the MSWS-12, and HRQoL, using the EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D), three-level descriptive system and visual analog scale (VAS) and the Short Form-12 (SF-12). Registrants who completed both the regular and supplemental semiannual surveys (the latter sent about 1 month after the close of the regularly scheduled survey) in spring 2010 were eligible for inclusion into this study.

The collection and research use of NARCOMS data is approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. A separate approval was obtained from the same IRB for the acquisition of the additional data via the supplemental semiannual questionnaire. The secondary analyses reported here were reviewed and approved by the IRB at Hartford Hospital and conducted with de-identified datasets.

The MSWS-12 is a validated PRO designed to evaluate patients’ perceived impact of MS on walking, using 12 different but related questions that patients respond to on a scale of 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”) [13]. Question 10 of the MSWS-12 was used in this study to assess the self-perceived impact of MS on the participants’ walking speed: “How much has your MS slowed down your walking?” Since the objective of this analysis is to focus on the effect of perceived walking speed, only this question of the MSWS-12 scale was used.

The SF-12 health survey was used to describe the health profile and calculate scores relative to that of the US population [mean = 50, standard deviation (SD) = 10] [14]. The SF-12 consists of eight individual domains (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health) that are each scored from 0 (worst health) to 100 (best health). The physical component scale (PCS) and mental component scale (MCS) scores were calculated from the appropriate individual domains.

Health status index scores were estimated using three generic instruments. The EQ-5D assesses five domains of HRQoL (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), scored on three levels (no problems, some problems, extreme problems), and is used to derive preference-weighted index scores [15]. The EQ-VAS consists of a vertical 20-cm VAS from 0 to 100, which is designed to evaluate an individual’s current HRQoL state. The Short Form-6 Dimension (SF-6D), which uses an algorithm to derive a single index value describing health status based on questions from the SF-12, was also utilized [16].

2.1 Data Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as means and SDs, while proportions were calculated for categorical variables. Correlations between MSWS-12 question 10 responses and HRQoL measures were assessed using Pearson’s rho statistics, with a coefficient <0.35 representing a weak, 0.36–0.67 a moderate, and 0.68–1.0 a strong correlation [17]. Comparisons across categories were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. General linear modeling was conducted to assess the impact of walking speed on the PCS, MCS, and each health status index score (each as the dependent variable) after adjusting for confounders including patient demographics and the severity of additional MS-related dysfunction and symptoms as measured by the NARCOMS Performance Scales [18] (bladder/bowel, hand, vision, cognitive, sensory, spasticity, pain and fatigue, but excluding mobility because of concerns of multicollinearity). All demographics including age, gender, employment status, use of physical therapy, disease duration, occurrence of a relapse within the previous 6 months, annual household income, and the use of a disease-modifying drug in the past 6 months, as well as additional MS-related disability and symptoms, were treated as fixed effects in the model. A p value of <0.05 was deemed statistically significant in all cases. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made. Analyses were performed using SPSS (version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3 Results

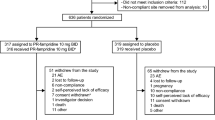

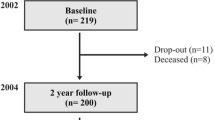

There were 9,899 respondents to the spring 2010 regular NARCOMS survey. Of these, 3,728 respondents with a PDDS ≤7 responded to the supplemental survey, and 3,670 (98.4 %) provided sufficiently complete data to be included in this analysis. Characteristics of these participants are reported in Table 1. The majority of participants were women over the age of 40 years with a diagnosis of MS for more than a decade. Approximately one-third of participants were not working or attending school. Only a fifth of participants experienced an MS relapse in the past 6 months and about two-thirds were receiving a disease-modifying drug at the time of query. While fewer than one out of five respondents (18.0 %) reported perceiving no effect on walking speed, almost half (49.1 %) reported that MS slowed their walking speed either “quite a bit” or “extremely.” Most patients experienced, to at least some degree, additional disability or symptoms related to MS.

Unadjusted analyses showed that reductions in norm-based SF-12 scores were consistently reported for all eight domains, as patients perceived an increased effect of MS on their walking speed (Table 2). Of these domains, the effect of walking speed on the physical functioning and role physical SF-12 domains was most profound (−0.73 and −0.64, respectively, p < 0.001 for both). Scores at each level of impact or MSWS-12 categorization were significantly lower relative to “not at all” for all SF-12 domains (p < 0.001 for all comparisons with the referent). SF-12-derived PCS and MCS scores at each level of impact or MSWS-12 question 10 categorization were significantly lower relative to “not at all” (p < 0.001 for both correlations). Significantly lower health index scores were also reported in respondents who perceived that their walking speed was more severely affected relative to “not at all,” when measured using EQ-VAS, EQ-5D, and SF-6D.

After adjustment for demographics and additional MS-related disability and symptoms, the impact of walking speed remained significant, although less profound for the PCS (reductions of 3.59–12.31 across walking speed classifications) and individual index scores (reductions ranging from 1.98 to 14.06, 0.04 to 0.13, and 0.02 to 0.07 for the EQ-VAS, EQ-5D, and SF-6D, respectively) (Table 3). Reduction in walking speed was no longer associated with a worse MCS (p > 0.05 all classifications of walking speed).

4 Discussion

Our analysis of data from the NARCOMS registry showed that reductions in general HRQoL and health index scores were seen with progressively worsening patient-perceived walking speed, even after adjustment for demographic factors and additional MS-related disability and symptoms. Similarly, reductions in health status index scores were seen with worsening walking speed across a number of accepted tools, including the ED-5D, EQ-VAS, and SF-6D.

Previous studies have evaluated the impact of motor dysfunction on HRQoL in patients with MS. To do so, these studies [1–3] utilized the clinician-rated EDSS or its close relative, the patient-rated PDDS; both disability assessments are heavily weighted towards walking ability in the middle portion of these ordinal scales. These studies have frequently demonstrated a statistically significant association between rising EDSS and PDDS scores (greater disability) and poorer HRQoL as measured by various health profile and health status index measures. However, it is important to note that mobility and walking impairment are not synonymous disabilities, as emphasized by the WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [5]. To this end, additional studies have more specifically evaluated the impact of walking disability [4], walking endurance [19], and walking speed on HRQoL as measured by the SF-12 or -36 [6–11, 19], the latter exclusively using the T25FW or 10-Meter Timed Walk (10MTW) test as objective measures of walking speed. While not consistently demonstrated throughout all these studies, a small but statistically significant (r < 0.50 for all) association was often observed between walking speed and HRQoL, suggesting that greater walking disability and slower walking speeds are associated with poorer HRQoL. To our knowledge, the present study is the first analysis to assess the relationship between patient-perceived walking speed and HRQoL using a PRO, and also the first to assess the relationship between walking speed and a health status index measure [19]. Our finding of statistically significant relationships between item 10 of the MSWS-12 and the various measures of HRQoL both supports and expands upon the findings of previous studies. One potential explanation for the larger magnitude of HRQoL decrement seen with worsening walking speed in our unadjusted analyses (moderate-to-large sized r values between −0.50 and −0.72 for the SF-12 PCS, physical functioning and role physical domains, as well as the EQ-5D index and VAS) as compared with previous studies, may be the result of using a PRO versus an objective functional measure like the T25FW or 10MTW. Unfortunately, since NARCOMS does not collect objective walking speed data, we are unable to further test this hypothesis.

There are some additional limitations of our analysis that require discussion. First, the NARCOMS registry served as the only source of data for this analysis. While NARCOMS is a large database, which allowed analysis of data from a larger patient population than the study mentioned above, this population may not be representative of all MS patients, particularly those living outside of North America. Moreover, NARCOMS data comes from semiannual surveys, and therefore, responses may be subject to reporting or recall bias and respondent burden may have been an issue as evidenced by the reduced number of respondents completing the supplemental questionnaire. Additionally, we used only one question from the validated MSWS-12 tool. While the use of this question allowed us to conduct a novel analysis assessing walking speed as a PRO, this question alone has not been formally evaluated for this purpose. Finally, our study could not address the paucity of medical literature assessing the relationship between walking speed or disability and MS-specific HRQoL measures identified by a recent systematic review of the literature [19].

5 Conclusions

Among MS respondents in this survey, decremental changes in HRQoL were observed as patients perceived greater levels of reduction in their walking speed.

References

Kobelt G, Berg J, Atherly D, et al. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study in the United States. Neurology. 2006;66:1696–702.

Fisk JD, Brown MG, Sketris IS, et al. A comparison of health utility measures for the evaluation of multiple sclerosis treatments. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:58–63.

Miller DM, Rudick RA, Cutter G, et al. Clinical significance of the multiple sclerosis functional composite: relationship to patient-reported quality of life. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1319–24.

Wu N, Minden SL, Hoaglin DC, et al. Quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis: data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2007;30:233–67.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) online English version; 2010. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/ (Accessed 16 Sep 2012).

Jeffery D, Kirzinger S, Halper J, et al. Health-related quality of life, EDSS and Timed 25-Foot Walk in a multiple sclerosis population of a real-world observational outcomes study: baseline data from ROBUST. Value Health. 2009;12:A372.

Robinson D Jr, Zhao N, Gathany T, et al. Health perceptions and clinical characteristics of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: baseline data from an international clinical trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:1121–30.

Hoogervorst EL, Zwemmer JN, Jelles B, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): relation to established measures of impairment and disability. Mult Scler. 2004;10(5):569–74.

Jongen PJ, Lehnick D, Sanders E, et al. Health-related quality of life in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis patients during treatment with glatiramer acetate: a prospective, observational, international, multi-centre study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:133.

Miller DM, Cohen JA, Kooijmans M, et al. Change in clinician-assessed measures of multiple sclerosis and subject-reported quality of life: results from the IMPACT study. Mult Scler. 2006;12:180–6.

O’Connor P, Lee L, Ng PT, et al. Determinants of overall quality of life in secondary progressive MS: a longitudinal study. Neurology. 2001;57:889–91.

U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services/Food and Drug Admin. Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims; 2009. http://www.ispor.org/workpaper/FDA%20PRO%20Guidance.pdf (Accessed Sep 16 2012).

Hobart JC, Riaza A, Lamping DL, et al. Measuring the impact of MS on walking ability: the 12-item MS Walking Scale (MSWS-12). Neurology. 2003;60:31–6.

Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al. How to score version 2 of the SF-12® Health Survey (with a supplement documenting version 1). Lincoln: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2002.

The EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004;42:851–9.

Taylor R. Interpretation of the correlation coefficient: a basic review. JDMS. 1990;1:35–9.

Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validity of performance scales for disability assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:1176–82.

Kieseier BC, Pozzilli C. Assessing walking disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18:914–24.

Acknowledgments

All authors have contributed substantially to the study and/or authoring the manuscript.

The following details the contribution of each author:

Dr. Coleman had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kohn, Baker, Sidovar, Coleman.

Acquisition of data: Sidovar, Coleman.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kohn, Baker, Sidovar, Coleman.

Drafting of the manuscript: Kohn, Baker, Sidovar, Coleman.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kohn, Baker, Sidovar, Coleman.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Sidovar, Coleman.

Study supervision: Coleman.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Coleman has received grant funding from Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. Mr. Sidovar is a paid employee of Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. and holds stock in the company. Drs. Kohn and Baker have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This research was funded by Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., Ardsely, NY. NARCOMS is supported by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers and its Foundation. The authors of this report take full responsibility for the integrity, accuracy, and contents of the report. The funding source reviewed the final manuscript. The authors approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kohn, C.G., Baker, W.L., Sidovar, M.F. et al. Walking Speed and Health‐Related Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis. Patient 7, 55–61 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-013-0028-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-013-0028-x