Abstract

Background

Older patients are regularly exposed to multiple medication changes during a hospital stay and are more likely to experience problems understanding these changes. Medication counselling is often proposed as an important component of seamless care to ensure appropriate medication use after hospital discharge.

Objectives

The purpose of this systematic review was to describe the components of medication counselling in older patients (aged ≥ 65 years) prior to hospital discharge and to review the effectiveness of such counselling on reported clinical outcomes.

Methods

Using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology (PROSPERO CRD42019116036), a systematic search of MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL was conducted. The QualSyst Assessment Tool was used to assess bias. The impact of medication counselling on different outcomes was described and stratified by intervention content.

Results

Twenty-nine studies were included. Fifteen different components of medication counselling were identified. Discussing the dose and dosage of patients’ medications (19/29; 65.5%), providing a paper-based medication list (19/29; 65.5%) and explaining the indications of the prescribed medications (17/29; 58.6%) were the most frequently encountered components during the counselling session. Twelve different clinical outcomes were investigated in the 29 studies. A positive effect of medication counselling on medication adherence and medication knowledge was found more frequently, compared to its impact on hard outcomes such as hospital readmissions and mortality. Yet, evidence remains inconclusive regarding clinical benefit, owing to study design heterogeneity and different intervention components. Statistically significant results were more frequently observed when counselling was provided as part of a comprehensive intervention before discharge.

Conclusions

Substantial heterogeneity between the included studies was found for the components of medication counselling and the reported outcomes. Study findings suggest that medication counselling should be part of multifaceted interventions, but the evidence concerning clinical outcomes remains inconclusive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Medication counselling in older patients was conducted by various methods resulting in the identification of 15 different components addressed during counselling sessions. |

The impact of medication counselling on clinical outcomes remains unclear as studies had variable methodological quality and heterogeneous study design. |

Statistically significant results were more frequently observed when counselling was provided as part of a comprehensive intervention before discharge. This may suggest that medication counselling should preferably be integrated into a holistic approach to ensure appropriate medication use in older patients after hospital discharge. |

High-quality trials with a proper description of the counselling intervention and long-term follow-up are needed to provide definitive evidence for the effect of medication counselling in this population. |

1 Introduction

Older patients are regularly exposed to a multitude of medication changes during a hospital stay, mostly owing to newly diagnosed conditions or drug therapy optimisation [1,2,3,4,5]. However, such drug regimen changes and resulting polypharmacy might put patients at risk of drug-related problems during and after hospital discharge [6,7,8]. Forster et al. demonstrated that approximately one in five patients experienced an adverse event after hospital discharge, of which more than two-thirds were drug related and the majority was considered to be preventable and/or ameliorable [7].

Importantly, instructions regarding drug therapy are not always communicated explicitly and adequately to patients or their caregivers upon discharge [9,10,11]. The lack of discharge instructions, together with the insufficient transfer of information to other healthcare providers, might further contribute to suboptimal therapy compliance in patients after discharge and could lead to avoidable harm [12,13,14]. Therefore, seamless care is required to ensure patient safety at care transitions [15].

Medication counselling prior to hospital discharge is often proposed as an important component of seamless care. Currently, a number of terms are used (e.g. medication counselling, medication education, medication consultation) to define the provision of medication information to the patients or their caregivers to ensure appropriate medication use. A systematic review conducted by Bonetti et al. which included patients of all ages, concluded however that components of discharge counselling varied greatly and that evidence of its impact on hospital readmissions and emergency department (ED) visits was lacking [16, 17].

Several additional issues add to the difficulty of providing direct counselling in old and very old patients. First, multimorbidity and polypharmacy are prevalent in older age [18], often leading to complex and difficult to comprehend medication regimens. Second, owing to age-related cognitive impairments, older patients face additional obstacles in understanding medical information. Third, older patients might have decreased physical abilities to use their medications appropriately [19]. Fourth, older people are more frequently hospitalised and experience more drug regimen changes [3, 20]. Consequently, they are more prone to experience problems understanding their medication regimens. This means that data from the younger or general population cannot be extrapolated as such to older patients [21].

Therefore, we aimed to provide an overview of reported components of medication counselling in older patients (aged ≥ 65 years) prior to hospital discharge. We also reviewed the effectiveness on the reported clinical outcomes such as hospital readmissions, medication adherence, medication knowledge and ED visits.

2 Methods

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [22]. The protocol of this systematic review was published in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42019116036.

2.1 Search Strategy

The following electronic databases were searched from inception until 12 December, 2018: MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL. Database alerts were defined, which provided the reviewers with updates to ensure new eligible publications were identified, until September 2019. The search strategy included terms to describe: (1) older patients, (2) medication counselling and (3) a hospital discharge setting. To identify relevant search terms for all concepts, we sought the expertise of content experts, explored Thesaurus, used pearl-growing, used text mining tools and tested multiple search filters. The Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were used, alongside phrase, proximity and truncation operators to increase sensitivity. The search syntax was adapted based on the individual databases and controlled vocabulary terms were used where available. All search strategies are outlined in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

2.2 Study Selection

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) more than half of the study population was aged older than 65 years; (2) counselling was medication related; (3) medication counselling was (the main part of) the intervention; (4) medication counselling was conducted in a hospital setting; (5) medication counselling was conducted prior to discharge; and (6) there was a sufficient description of the intervention. Citations not reported in English and/or not reporting primary data were excluded. There was no restriction for study design or outcomes studied as a small number of studies eligible for inclusion were expected.

All records retrieved using the search strategy were exported into the reference manager EndNote X9.1 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). After duplicate removal, the records were imported into Rayyan© QCRI to perform the study selection [23]. All references were scanned based on titles and/or abstracts by one reviewer (AC). A duplicate review was conducted independently by different reviewers (AS, MP, KF, LVDL, KW, JH, AS, ALS) to ensure that each reference was reviewed by at least two independent reviewers. Next, all full texts of the provisionally included records were reviewed by the same independent authors against the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion if necessary.

2.3 Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A pre-agreed standardised data extraction form was used to collect data of the included studies. The following items were extracted from the published articles: study items (author(s), year of publication, country, study design, setting); participants’ characteristics (sample size, age, sex); intervention description (provider of the intervention, complementary interventions in adjunct to medication counselling); and outcome(s) studied (follow-up time, outcome measures, results).

To assess the risk of bias for the included studies, the QualSyst Assessment Tool for quantitative research was used from the “Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields” [24]. This validated tool was used because it is not restricted to one study design and can be applied to all studies included. It is a 14-item checklist in which each item was scored as “yes” = 2, “partial” = 1 or “no” = 0, depending on the degree to which the specific criteria were met or reported, creating a maximum score of 28. For non-randomised studies, the item about random allocation was not applicable. Because of the nature of the intervention, which made blinding of personnel and participants impossible, the two items of blinding were not applicable for any of the included studies and were hence excluded from the calculation of the summary score. A percentage was calculated for each paper by dividing the total sum score obtained across rated items by the total possible score [i.e. 28 − (number of not applicable items × 2)] and ranged between 0 and 100%. A score of < 50% or ≥ 80% was defined as a low or a high methodological quality, respectively. The quality of the included articles was assessed by three independent reviewers (AC, AS, MP).

2.4 Data Synthesis

As the high heterogeneity of included studies precluded a quantitative analysis (i.e. meta-analysis), a descriptive approach was followed. The impact of medication counselling on different outcomes was described and stratified by intervention content (studies with medication counselling as a sole intervention vs studies with complementary interventions in adjunct to medication counselling) and by methodological quality (low vs moderate to high methodological quality). Hence, the association between type of intervention, methodological quality and outcome could be investigated.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative variables were described using the mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range = Q1–Q3) depending on whether they followed a normal distribution, which was assessed descriptively (skewness, kurtosis), graphically (Q–Q plot and boxplot) and with tests of normality (Shapiro–Wilk).

3 Results

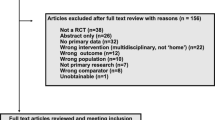

The literature search resulted in 4358 abstracts. After screening titles and abstracts, 129 records were assessed for full-text analysis of which 29 were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. The article selection process with reasons for exclusion can be found in Fig. 1.

3.1 Characteristics of Included Studies

Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. In total, 7574 patients were included, with a median number of 162 patients (interquartile range = 85–345) per study. Articles were published between 1977 and 2018. The majority of the studies was conducted in Europe (16/29; 55.2%) [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], followed by studies conducted in the USA (8/29; 27.6%) [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Three studies were conducted in Australia [49,50,51], one in Brazil [52] and one in Israel [53]. Sixteen studies (55.2%) had a randomised controlled study design [25,26,27, 30, 31, 35,36,37,38,39,40, 42,43,44, 47, 52], the other studies (13/29; 44.8%) were non-randomised [28, 29, 32,33,34, 41, 45, 46, 48,49,50,51, 53]. The studies were mainly conducted at an internal medicine ward (9/29; 31.0%) [26, 30, 32, 33, 38, 39, 44, 50, 53], a geriatric ward (6/29; 20.7%) [25, 29, 34, 36, 47, 51] or a medical admission unit (4/29; 13.8%) [27, 28, 31, 37]. In seven studies (7/29; 24.1%), the counselling intervention was conducted on all wards in the hospital [35, 40,41,42,43, 45, 48]. The majority of studies excluded patients who were not discharged to their homes (21/29; 72.4%) and/or were cognitively impaired (18/29; 62.1%).

3.2 Quality Assessment

The included studies showed a variable quality score ranging from 31.8 to 95.8% (Table 1). The mean methodological quality score of the studies was 66.2% ± 18.3%. Six out of 29 studies had low methodological quality (< 50%) [28, 29, 34, 41, 48, 49] and eight studies had high methodological quality (≥ 80%) [26, 30, 31, 35,36,37, 43, 52].

3.3 Components of Counselling Interventions

In a majority of studies (23/29; 79.3%), pharmacists were involved in performing medication counselling at hospital discharge. In some studies, nurses (6/29; 20.7%) or physicians (2/29; 6.9%) were also involved. Counselling components varied widely between studies (Fig. 2). The most frequently encountered components during counselling sessions were “discussing the dose and dosage of patients’ medications” (19/29; 65.5%) and “providing a paper-based medication list” (19/29; 65.5%), followed by “explanation of the indications of the prescribed medications” (17/29; 58.6%). Furthermore, in 12 studies (12/29; 41.4%), potential adverse drug reactions that patients might experience during therapy were addressed. Information about medications stopped, newly started drugs and drugs that were changed (e.g. altered dose or frequency) were part of the counselling process in eight studies (8/29; 27.6%). In six studies (6/29; 20.7%), the importance of medication adherence was stressed during the session. Other components of medication counselling were information about the storage of medications, instructions on how to deal with missed doses, dietary and lifestyle education, information about the benefits of therapy, the cost of therapy and explanation of therapeutic goals. Five studies (5/29; 17.2%) used the teach-back method to ensure patients understood the instructions provided.

Upon hospital discharge, complementary interventions, in adjunct to medication counselling, were performed in 16 studies (16/29; 55.2%) (Table 2). Medication review (10/29; 34.5%), medication reconciliation (6/29; 20.7%) and telephone follow-up of patients post-discharge (6/29; 20.7%) were most frequently reported. In addition, three studies already conducted inpatient medication counselling during hospitalisation. Home-based patient visits (3/29; 10.3%) and the use of a medication telephone helpline (2/29; 6.9%) were also reported in addition to medication counselling.

3.4 Outcome Measures for Discharge Medication Counselling

The impact of discharge medication counselling was measured on 12 different outcomes, with the following being most common: hospital readmissions (14/29; 48.3%), medication adherence (12/29; 41.4%), medication knowledge (8/29; 27.6%), ED visits (6/29; 20.7%) and mortality (3/29; 10.3%) (Table 3).

Overall, in 20 studies (20/29; 69.0%), statistically significant findings on at least one of the measured outcome indicators were found. A significant result was found more frequently in studies that evaluated the impact on medication knowledge and medication adherence with seven out of eight studies and 9 out of 12 studies, respectively. One-third of studies demonstrated a significant impact of the intervention on hospital readmissions (5/14; 35.7%) and ED visits (2/6; 33.3%). A reduction in mortality was not reported. Taking into account the reported sample sizes, a higher proportion of statistically significant findings was observed in studies with a higher number of enrolled participants. Additionally, studies where medication counselling was combined with other interventions and studies with a moderate to high methodological quality found more frequently statistically significant results (Table 3).

4 Discussion

This systematic review identified 29 studies that assessed the impact of medication counselling in older patients prior to hospital discharge. Medication counselling was most commonly performed by pharmacists and conducted in various methods with 15 different components identified. Medication lists, medication dosages and the indications of the prescribed medications were most commonly discussed during counselling sessions. However, although older patients experience a multitude of medication changes during a hospital stay, remarkably little emphasis was placed on that topic during the counselling sessions. We observed that less than one-third of the studies discussed such therapy changes during the counselling process. However, this does not necessarily imply that medication changes were not identified. Indeed, medication reconciliation was often combined with the counselling intervention, and this includes highlighting and communicating treatment changes.

Across the 29 included studies, we identified 12 different outcomes with hospital readmissions, medication adherence, medication knowledge and ED visits having been most frequently investigated. Briefly, the impact of medication counselling on clinical outcomes remains inconclusive. Studies that evaluated associations between counselling and medication adherence or medication knowledge reported statically significant findings more frequently compared with studies with hard outcomes such as hospital readmissions, ED visits and mortality.

Mainly, the impact of medication counselling on clinical outcomes remains unclear as studies were heterogeneous in design and components of the intervention. Furthermore, a large variety in methodological quality was detected and for most studies the duration of follow-up was short with only eight studies following patients for longer than 3 months. Therefore, the lack of positive results of medication counselling may be attributable in part to the methodological quality, insufficient sample sizes and short follow-up period.

Previously, it has been shown that it is complex to prove the impact of pharmaceutical care interventions on healthcare utilisation (such as hospital readmissions and ED visits) and mortality [54,55,56]. Because of the complex nature of pharmaceutical care interventions, it has been suggested to rather evaluate the impact on endpoints that are more patient related such as quality of life, the prevalence of drug-related problems, knowledge, adherence and patient satisfaction [57].

In more than half of the included studies, medication counselling was accompanied by other interventions such as medication reconciliation, medication review and telephone follow-up of patients post-discharge. These studies found statistically significant findings more frequently compared with studies where medication counselling was conducted as the sole intervention. This finding may suggest that medication counselling should hence preferably be integrated into a holistic approach to ensure appropriate medication use in older patients after hospital discharge. This approach, with positive findings on hospital readmissions, consists of a patient-centred medication review, medication reconciliation and motivational counselling at discharge, as well as contact with the primary caregivers and follow-up after discharge [37]. It was also acknowledged in the systematic review of Burke et al. that such multifaceted interventions are necessary to substantially improve the transition of care [54]. Other studies have also shown that a single pharmaceutical care intervention has no clear effect on itself [58,59,60].

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

The present systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement [22] and the protocol of the review was published on PROSPERO. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to evaluate the impact of medication counselling prior to hospital discharge, specifically in older patients. Additionally, we described the different components of medication counselling. However, this study also has several limitations. First, because of the high heterogeneity of the included studies, a meta-analysis could not be performed and the results were discussed only descriptively. In addition, it was not possible to identify which components were associated with improved clinical outcomes and should subsequently be provided as part of successful medication counselling. Second, other interventions should also be taken into account when evaluating the impact of medication counselling, such as a medication review during hospitalisation and a medication reconciliation at admission and discharge, as it is likely that this will have impacted the individual study findings. However, it was not always clearly stated in the included studies if other interventions were performed and what comprised those interventions. In addition, it is unfeasible to clearly determine the degree that each part contributed to possible demonstrated effects. Third, as data were only extracted from the published articles and we did not contact the authors to confirm or receive additional or more detailed information, this could have resulted in an inadequate reporting of the counselling intervention. Fourth, only published studies were included and we did not consider the grey literature such as conference papers or unpublished initiatives, which could have led to publication bias. Finally, we included only articles published in English and may, therefore, have missed some relevant studies.

4.2 Future Perspectives

Almost three-quarters of studies excluded patients who were not discharged to their homes and more than 60% excluded patients with cognitive impairments. Importantly, older patients are often discharged from the hospital to healthcare facilities and frequently experience cognitive impairments and are therefore underrepresented in the studies. This may limit the external validity of the study findings to complex older patients who might require long-term institutional care. Moreover, it remains unclear how medication counselling should be performed and adapted to this specific population. Future studies should therefore consider these aspects to provide the important information that is currently lacking.

As discussed above, clinical pharmacy services, such as medication counselling, are often insufficiently described with inconsistent definitions of the components of the interventions. Consequently, there is a need for high-quality well-designed trials with a proper description of the counselling intervention and a long-term follow-up to provide definitive evidence for the effect of medication counselling [61]. Therefore, reporting guidelines such as the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) and the Reporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collect health Date (RECORD) statements should be used. Furthermore, core outcome sets should be defined to standardise several outcomes [62]. This will allow comparisons between studies and may enable identification of the true effect of the interventions. In this manner, we believe high-level evidence will be provided to identify effective strategies that will guide us to optimal medication use in older patients. Potentially, the ongoing MedBridge trial in Sweden might provide more robust information with high external validity. This trial studies the effects of a comprehensive intervention with an active follow-up on older patient’s healthcare utilisation and is sufficiently powered to detect the impact of the intervention [63]. Last, it might be essential to investigate which conditions should be available and fulfilled to provide a model for a multifaceted approach including medication counselling. We would like to translate this multifaceted approach to a practical guideline that can be used by geriatricians, clinical pharmacists and geriatric nurses in real-life clinical practice.

5 Conclusions

This systematic review evaluated the impact of medication counselling in older patients prior to hospital discharge. Substantial heterogeneity between the included studies was found for the components of medication counselling, the reported outcomes as well as the methodological quality. Study findings suggest that medication counselling should be part of multifaceted interventions, but the evidence with regard to clinical outcomes remains inconclusive.

References

Mansur N, Weiss A, Beloosesky Y. Relationship of in-hospital medication modifications of elderly patients to postdischarge medications, adherence, and mortality. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(6):783–9. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1L070.

Beers MH, Dang J, Hasegawa J, Tamai IY. Influence of hospitalization on drug therapy in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(8):679–83.

Harris CM, Sridharan A, Landis R, Howell E, Wright S. What happens to the medication regimens of older adults during and after an acute hospitalization? J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):150–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0b013e318286f87d.

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Eek AK, Davies MN, Moger TA, Reikvam A. How are drug regimen changes during hospitalisation handled after discharge: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001461. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001461.

Grimmsmann T, Schwabe U, Himmel W. The influence of hospitalisation on drug prescription in primary care: a large-scale follow-up study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(8):783–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-007-0325-1.

Paulino EI, Bouvy ML, Gastelurrutia MA, Guerreiro M, Buurma H. Drug related problems identified by European community pharmacists in patients discharged from hospital. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26(6):353–60.

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–7.

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(4):317–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30390.x.

Knight DA, Thompson D, Mathie E, Dickinson A. ‘Seamless care? Just a list would have helped!’ Older people and their carer’s experiences of support with medication on discharge home from hospital. Health Expect. 2013;16(3):277–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00714.x.

Daliri S, Bekker CL, Buurman BM, Scholte Op Reimer WJM, van den Bemt BJF, Karapinar-Carkit F. Barriers and facilitators with medication use during the transition from hospital to home: a qualitative study among patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):204. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4028-y.

Cua YM, Kripalani S. Medication use in the transition from hospital to home. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(2):136–46.

Uitvlugt EB, Siegert CE, Janssen MJ, Nijpels G, Karapinar-Carkit F. Completeness of medication-related information in discharge letters and post-discharge general practitioner overviews. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(6):1206–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0187-z.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.8.831.

Kattel S, Manning DM, Erwin PJ, Wood H, Kashiwagi DT, Murad MH. Information transfer at hospital discharge: a systematic review. J Patient Saf. 2016;16(1):e25–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/pts.0000000000000248.

Tomlinson J, Cheong VL, Fylan B, Silcock J, Smith H, Karban K, et al. Successful care transitions for older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of interventions that support medication continuity. Age Ageing. 2020 afaa002. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa002.

Bonetti AF, Reis WC, Lombardi NF, Mendes AM, Netto HP, Rotta I, et al. Pharmacist-led discharge medication counselling: a scoping review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(3):570–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12933.

Bonetti AF, Reis WC, Mendes AM, Rotta I, Tonin FS, Fernandez-Llimos F, et al. Impact of pharmacist-led discharge counseling on hospital readmission and emergency department visits: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):52–9. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3182.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60240-2.

Kessels RP. Patients’ memory for medical information. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(5):219–22. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.96.5.219.

Bagge M, Norris P, Heydon S, Tordoff J. Older people’s experiences of medicine changes on leaving hospital. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2014;10(5):791–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.10.005.

Tan ECK, Sluggett JK, Johnell K, Onder G, Elseviers M, Morin L, et al. Research priorities for optimizing geriatric pharmacotherapy: an international consensus. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(3):193–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.002.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Kmet L, Lee R, Cook, L. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. 2004. Available from: https://www.ihe.ca/advanced-search/standard-quality-assessment-criteria-for-evaluating-primary-research-papers-from-a-variety-of-fields. Accessed 20 Feb 2020.

Al-Rashed SA, Wright DJ, Roebuck N, Sunter W, Chrystyn H. The value of inpatient pharmaceutical counselling to elderly patients prior to discharge. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(6):657–64. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01707.x.

Bladh L, Ottosson E, Karlsson J, Klintberg L, Wallerstedt SM. Effects of a clinical pharmacist service on health-related quality of life and prescribing of drugs: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(9):738–46. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2009.039693.

Bolas H, Brookes K, Scott M, McElnay J. Evaluation of a hospital-based community liaison pharmacy service in Northern Ireland. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26(2):114–20. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PHAR.0000018601.11248.89.

Brookes K, Scott MG, McConnell JB. The benefits of a hospital based community services liaison pharmacist. Pharm World Sci. 2000;22(2):33–8. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008713304892.

Drenth-van Maanen AC, Wilting I, Jansen PAF, Marum RJ, Egberts TCG. Effect of a discharge medication intervention on the incidence and nature of medication discrepancies in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):456–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12117.

Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D, Garmo H, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Toss H, et al. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(9):894–900. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.71.

Graabaek T, Hedegaard U, Christensen MB, Clemmensen MH, Knudsen T, Aagaard L. Effect of a medicines management model on medication-related readmissions in older patients admitted to a medical acute admission unit: a randomized controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019 Feb;25(1):88–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13013.

Greissing C, Buchal P, Kabitz HJ, Schuchmann M, Zantl N, Schiek S, et al. Medication and treatment adherence following hospital discharge. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(44):749–56. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2016.0749.

Leguelinel-Blache G, Dubois F, Bouvet S, Roux-Marson C, Arnaud F, Castelli C, et al. Improving patient’s primary medication adherence: the value of pharmaceutical counseling. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1805. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000001805.

MacDonald ET, MacDonald JB, Phoenix M. Improving drug compliance after hospital discharge. Br Med J. 1977;2(6087):618–21.

Marusic S, Gojo-Tomic N, Erdeljic V, Bacic-Vrca V, Franic M, Kirin M, et al. The effect of pharmacotherapeutic counseling on readmissions and emergency department visits. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(1):37–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-012-9700-9.

Nazareth I, Burton A, Shulman S, Smith P, Haines A, Timberal H. A pharmacy discharge plan for hospitalized elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2001;30(1):33–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/30.1.33.

Ravn-Nielsen LV, Duckert ML, Lund ML, Henriksen JP, Nielsen ML, Eriksen CS, et al. Effect of an in-hospital multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on the risk of readmission: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):375–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8274.

Raynor DK, Booth TG, Blenkinsopp A. Effects of computer generated reminder charts on patients’ compliance with drug regimens. BMJ. 1993;306(6886):1158–61.

Scullin C, Scott MG, Hogg A, McElnay JC. An innovative approach to integrated medicines management. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(5):781–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00753.x.

Smith L, McGowan L, Moss-Barclay C, Wheater J, Knass D, Chrystyn H. An investigation of hospital generated pharmaceutical care when patients are discharged home from hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44(2):163–5.

Donihi AC, Yang E, Mark SM, Sirio CA, Weber RJ. Scheduling of pharmacist-provided medication education for hospitalized patients. Hosp Pharm. 2008;43(2):121–6.

Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L, Cohen BA, Prengler ID, Cheng D, et al. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):211–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.427.

Lipton HL, Bird JA. The impact of clinical pharmacists’ consultations on geriatric patients’ compliance and medical care use: a randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist. 1994;34(3):307–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/34.3.307.

Manning DM, O’Meara JG, Williams AR, Rahman A, Myhre D, Tammel KJ, et al. 3D: a tool for medication discharge education. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):71–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2006.018564.

Moye PM, Chu PS, Pounds T, Thurston MM. Impact of a pharmacy team-led intervention program on the readmission rate of elderly patients with heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(4):183–90. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp170256.

Szkiladz A, Carey K, Ackerbauer K, Heelon M, Friderici J, Kopcza K. Impact of pharmacy student and resident-led discharge counseling on heart failure patients. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(6):574–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190013491768.

Vinluan CM, Wittman D, Morisky D. Effect of pharmacist discharge counselling on medication adherence in elderly heart failure patients: a pilot study. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2015;6(2):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphs.12093.

Wolfe SC, Schirm V. Medication counseling for the elderly: effects on knowledge and compliance after hospital discharge. Geriatr Nurs. 1992;13(3):134–8.

Hawe P, Higgins G. Can medication education improve the drug compliance of the elderly? Evaluation of an in hospital program. Patient Educ Couns. 1990;16(2):151–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-3991(90)90090-8.

Leung CH, Chong C, Lim WK. Medical student-led patient education prior to hospital discharge improves 1-month adherence rates. Intern Med J. 2017;47(3):328–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.13365.

Shen Q, Karr M, Ko A, Chan DKY, Khan R, Duvall D. Evaluation of a medication education program for elderly hospital in-patients. Geriatr Nurs. 2006;27(3):184–92.

Bonetti AF, Bagatim BQ, Mendes AM, Rotta I, Reis RC, Favero MLD, et al. Impact of discharge medication counseling in the cardiology unit of a tertiary hospital in Brazil: a randomized controlled trial. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e325. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2018/e325.

Bisharat B, Hafi L, Baron-Epel O, Armaly Z, Bowirrat A. Pharmacist counseling to cardiac patients in Israel prior to discharge from hospital contribute to increasing patient’s medication adherence closing gaps and improving outcomes. J Transl Med. 2012;10(1):34.

Burke RE, Guo R, Prochazka AV, Misky GJ. Identifying keys to success in reducing readmissions using the ideal transitions in care framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:423. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-423.

Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–8. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008.

Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2(2):CD008986. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.

Kjeldsen LJ, Nielsen TR, Olesen C. The challenges of outcome research. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):705–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0293-6.

Holland R, Desborough J, Goodyer L, Hall S, Wright D, Loke YK. Does pharmacist-led medication review help to reduce hospital admissions and deaths in older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65(3):303–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03071.x.

Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD000011. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd000011.pub4.

Kwan JL, Lo L, Sampson M, Shojania KG. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 Pt 2):397–403. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00006.

Ensing HT, Stuijt CC, van den Bemt BJ, van Dooren AA, Karapinar-Carkit F, Koster ES, et al. Identifying the optimal role for pharmacists in care transitions: a systematic review. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(8):614–36. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.8.614.

Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR, King-Jones S, Ishaque S, Bhaloo Z, et al. Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative: protocol for an international Delphi study to achieve consensus on how to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a ‘core outcome set’. Trials. 2014;15:247. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-247.

Kempen TGH, Bertilsson M, Lindner KJ, Sulku J, Nielsen EI, Hogberg A, et al. Medication Reviews Bridging Healthcare (MedBridge): study protocol for a pragmatic cluster-randomised crossover trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;61:126–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2017.07.019.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the executive board of the Belgian Society for Gerontology and Geriatrics (BSGG), which includes the following members: Jean-Pierre Baeyens, Ivan Bautmans, Nicolas Berg, Katrien Cobbaert, Isabelle de Brauwer, Sandra de Breucker, Anne Marie de Cock, Marie de Saint Hubert, Johan Flamaing, Sophie Gillain, Tony Mets, Nele Van Den Noortgate.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: AC, AS and MP designed the study; AC developed the search strategy and performed the literature search; all authors conducted the review; AC, AS and MP performed the data extraction and quality assessment; AC wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors revised the manuscript, approved the final version and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the Belgian Society for Gerontology and Geriatrics (BSGG).

Conflict of interest

Andreas Capiau, Katrien Foubert, Lorenz Van der Linden, Karolien Walgraeve, Julie Hias, Anne Spinewine, Anne-Laure Sennesael, Mirko Petrovic and Annemie Somers have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capiau, A., Foubert, K., Van der Linden, L. et al. Medication Counselling in Older Patients Prior to Hospital Discharge: A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging 37, 635–655 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-020-00780-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-020-00780-z