Abstract

Background

Deprescribing has been shown to reduce potentially inappropriate or unnecessary medications; however, whether these benefits translate into improved quality of life (QOL) is uncertain.

Objective

The objective of this study was to isolate the impact of deprescribing on patient or designated representative reported QOL; satisfaction with care (SWC) and emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations were also investigated to further explore this question.

Methods

This systematic review searched the Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), MEDLINE, and EMBASE from database inception until November 2017. Randomized controlled trials and non-randomized prospective studies of older adults (> 65 years or older) and older persons with life-limiting conditions were included. Two reviewers independently assessed the search results and performed risk of bias assessments. Data on QOL, SWC, and ED visits and hospitalizations were extracted from all identified studies. Risk of bias of individual studies was assessed using measures recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.

Results

Screening of 6543 eligible records identified 12 studies within 13 articles. In ten studies investigating the reduction of at least one medication deprescribed, compared with usual care, all but two found no difference in QOL. To date there has only been one study examining the impact of deprescribing on SWC, which was found to be not statistically significant. Four studies exploring the impact of deprescribing on ED visits and hospitalizations also found no significant difference. However, many studies were found to have a higher performance, detection, or other bias. We found considerable heterogeneity in patient populations, targeted medications for deprescribing, and QOL measurements used in these studies.

Conclusion

Based on a limited number of studies with varying methodological rigor, deprescribing may not significantly improve QOL or SWC; however, it may not contribute to additional ED visits and hospitalizations. Future controlled studies are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Studies isolating the impact of deprescribing on patient or designated representative reported quality of life (QOL) have included various patient populations, targeted medications for deprescribing, and measurements. |

Current literature suggests that while deprescribing may not significantly improve QOL or satisfaction with care, it also may not contribute to additional emergency department visits and hospitalizations. |

Future controlled studies are needed. |

1 Introduction

Older adults often carry a significant medication burden. In a sample of Medicare beneficiaries discharged from an acute hospitalization to a skilled nursing facility, older adults were prescribed an average of 14 medications [1]. Unfortunately, many of these medications are potentially inappropriate or unnecessary. A 2016 systematic review of inappropriate medication use found almost 50% of older nursing home residents are exposed to such medications, and a 2018 systematic review of older hospital inpatients reported an even higher prevalence of up to 97% [2, 3].

Exposure to potentially inappropriate or unnecessary medications may decrease an individual’s quality of life (QOL). A cross-sectional analysis of 541 older adults from 17 nursing homes found there was a significant association between potentially inappropriate medications and lower QOL scores [4]. Use of these medications increases the complexity of the regimen and may lead to a higher symptom burden (via therapeutic failures, medication non-adherence, adverse drug events, medication adverse effects, and drug–drug interactions) [5, 6]. Higher symptom burden, in turn, has also been shown to lower QOL [7, 8].

Deprescribing is a recommended intervention to reverse the potential iatrogenic harms of these medications. According to Scott and colleagues [9], deprescribing is defined as the “systematic process of identifying and discontinuing medications in instances in which existing or potential harms outweigh existing or potential benefits within the context of an individual patient’s care goals, current level of functioning, life expectancy, values, and preferences”. Deprescribing interventions have been shown to decrease potentially inappropriate or unnecessary medications, thus reducing drug-related issues such as adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and falls, without a decline in neuropsychiatric symptoms or cognitive function [10,11,12]. However, whether these benefits translate into improved QOL as a result of deprescribing is uncertain.

In contrast, deprescribing may also induce negative consequences for patients that may compete with potential QOL benefits. A systematic review by Reeve and colleagues [13] noted “fear of cessation” as one of the largest patient barriers to deprescribing. This fear includes “psychological issues related to cessation” and “fear of return to [the] previous condition” [13]. Patients’ concerns regarding cessation may include experiencing a sense of futility from previous efforts with compliance, a further confirmation of mortality, and feelings of abandonment by medical professionals [14]. These concerns could translate to a decrease in a patient’s satisfaction with the healthcare system.

Concerns related to “returning to the previous condition” could include unplanned healthcare visits such as emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations. These are often prompted by ADRs or, in the case of deprescribing, adverse drug withdrawal events (ADWEs), which present as symptoms or syndromes. A 2012 retrospective cohort of 678 randomly selected unplanned hospitalizations of older veterans found polypharmacy (defined as nine or more medications) was associated with a greater risk of ADR-related hospitalizations (adjusted odds ratio = 3.90, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.43–10.61) [15]. These visits rob patients of meaningful time with family and friends, can reduce functional abilities temporarily or permanently, and can result in unforeseen costs. Further, ED visits and hospitalizations also often infer the additional prescribing of medications—once again adding to the regimen’s complexity.

There have been few studies directly exploring the impact of deprescribing on QOL, as well as satisfaction with care (SWC) and ED visits or hospitalizations. The largest, to date, is a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis by Page and colleagues [16]. The authors found deprescribing was not associated with changes in QOL, but they did not explore the impact of deprescribing on SWC, ED visits, or hospitalizations. To be included in the review, the authors did not require interventions to include only the explicit act of deprescribing; i.e., some interventions consisted of education to healthcare providers regarding the appropriateness of medications, or the performance of medication reviews by healthcare providers. Thus, this systematic review may have included interventions that did not result in the deprescribing of any medications and may have also resulted in the initiation of medications. In addition, some included studies assessed QOL by researcher rating, as opposed to patient or designated representative rating, which could have resulted in significant measurement error and/or bias [17].

A second systematic review and meta-analysis published by Thillainadesan and colleagues [10] examined the impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalized patients [10]. QOL and hospitalizations were two of the secondary outcomes, and it included five studies (one which explored both outcomes) [18,19,20,21,22]. The authors noted the impact of deprescribing on QOL was mixed, and the impact on hospitalizations was no different when compared with usual care. Again, the explicit act of deprescribing was not required; the five included studies all comprised a pharmacist-led intervention.

Given the potential for both positive and negative QOL impacts as a result of deprescribing, and limitations of past reviews on this topic, our objective was to conduct a systematic review isolating the effect of deprescribing interventions on patient- or designated representative-reported QOL. We also sought to explore the impact of deprescribing on SWC and ED visits and hospitalizations as secondary outcomes to further investigate this question.

2 Methods

2.1 Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Institute of Medicine guidelines, reported in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and listed on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; protocol: CRD42017078534) [23, 24].

This systematic review included published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized prospective studies. Inclusion criteria included studies of older adults (≥ 65 years) and studies of older persons with life-limiting conditions, in which at least one medication was deprescribed versus usual care. Life-limiting conditions included dementia (all subtypes), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic heart failure, chronic kidney disease (any stage), cancer (any stage), and any life-limiting neurological or hematological disease such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cystic fibrosis, multiple sclerosis, or sickle cell anemia. It also included any participants receiving palliative and/or hospice care services per study design. Targeted medications for deprescribing could include any prescription or over-the-counter medication. Only studies in the English language were included.

We excluded studies involving people < 65 years of age and studies in which the explicit act of deprescribing was not required. Many deprescribing-focused studies include educational sessions or a pharmacist or other healthcare provider medication review as the sole intervention; we chose to exclude these studies due to heterogeneity. Finally, studies where QOL or SWC were determined by researcher rating were also excluded.

2.2 Search Strategy and Study Selection

We performed a comprehensive review of the literature, supplemented by additional targeted and focused searches. The Cochrane Library (Wiley), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), MEDLINE via PubMed, and EMBASE were searched from database inception until November 2017. Search strategies utilized terminology beyond the recently added controlled vocabulary term for “deprescriptions”. Related vocabulary and keywords were combined with palliative care, nursing home, aged, drug and outcome (including QOL) terms using Boolean logic. The draft final strategy was piloted and sent to the team for review. After approval, the final strategy (Electronic Supplementary Material Online Resource 1) was translated into each database’s vocabulary, command language, and syntax. Retrievals were limited to English and downloaded into EndNote software (Clarivate Analytics, Boston, MA, USA) where duplicates were removed. References of included systematic reviews were also screened for additional studies.

2.3 Data Extraction and Assessment of Risk of Bias

Two reviewers (JAP and SS) independently reviewed each title and abstract to determine eligibility for study inclusion. A full article review was conducted if any uncertainty was present regarding eligibility during the title and abstract review and was completed for all studies included. The following data were collected from each included study: author, year, study design, patient population, sample size, intervention and control, QOL measure, SWC measure, and ED visits and hospitalization measure. Outcome variables were extracted at all timepoints available in an attempt to determine possible relationships. All studies (randomized and non-randomized) were evaluated for risk of bias using measures recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration [25, 26]. In the case of disagreement between the two reviewers, the article was discussed at length and if necessary a third reviewer (CTT) was asked to make a final decision. Search results and risk of bias assessments were recorded via DistillerSR, an online systematic review software (http://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software/).

2.4 Data Analysis

Meta-analyses were not performed due to the heterogeneity in study populations, outcome measures, and methodological rigor of included studies.

3 Results

3.1 Description of Studies

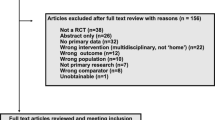

A total of 6543 citations were screened for eligibility, with 13 meeting the criteria (Fig. 1, Tables 1, 2, 3) [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Two citations included separate outcomes from the same study [33, 37]. Ten of the included studies addressed the primary outcome (QOL), one study addressed SWC, and four addressed ED visits and hospitalizations [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. A total of 2195 enrolled participants from ten different countries were included, with mean ages ranging from 70 to 86 years [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Nine studies had a patient population with > 50% females [27,28,29, 31,32,33,34, 36,37,38]. Studies focused on a variety of life-limiting conditions: for example, Bergh et al. [28] targeted patients with dementia and Kutner et al. [30] included 48% of patients with a malignant tumor. Two studies assessed successful versus unsuccessful discontinuation [29, 31]. The intervention setting varied greatly; four studies were conducted in community-dwelling adults, four studies were conducted in nursing homes, one study was conducted in hospitalized patients, and three studies included alternative facilities such as residency care facilities or palliative care settings [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Five studies targeted ‘unnecessary or non-beneficial medications’ per the study protocol (various, including antianginals, antihypertensives, laxatives, vitamins, and lipid drugs), while seven studies targeted specific medication classes, including antihypertensives (e.g., β-blockers [β-adrenergic antagonists], statins [HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors], selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or benzodiazepines) [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Only one study utilized a placebo capsule for the discontinued medication instead of reducing pill burden [28]. A majority of the studies utilized a tapering procedure to reduce the dose and eventually discontinue the medication [27,28,29, 31,32,33,34, 37, 38]. Follow-up after intervention ranged from 4 weeks to 24 months [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

3.1.1 Quality of Life

Ten studies compared patient- or designated representative-reported QOL in those who deprescribed at least one medication versus usual care. Most studies found no difference in QOL [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Only one randomized, multicentered, pragmatic study of older adults with serious illness, who received a statin for 3 months or longer for both primary or secondary prevention found total QOL to be significantly higher for patients in the statin discontinuation group (n = 381; mean McGill QOL score 7.11 vs. 6.85; p = 0.04) [30]. A non-randomized, pseudo-experimental study of long-term (> 6 months) benzodiazepine users observed an improvement of QOL in those who discontinued and maintained abstinence from benzodiazepines at 24 months (n = 51; mean Short Form Health Survey, 12 item [SF-12] score 49.27 vs. 40.72; p = 0.02) [31]. Lastly, a prospective, multicenter RCT investigating the effect of withdrawal of fall risk-increasing drugs (FRIDs) (e.g., cardiovascular drugs, psychotropics, anticholinergics, antispasmodics, α-blockers, corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-gout medications, hydroquinine, respiratory adrenergics, cough suppressants, and antihistamines) versus usual care on QOL found the control group had a greater decline during the 12-month follow-up than the intervention group using one measure, but noted scores did not differ significantly between groups (n = 612; EuroQoL Visual Analogue Scale [EQ-5D] score changes from baseline 0.01 vs. − 0.04 [p = 0.02]; SF-12 physical component summary (PCS) scores at 12-month follow-up 43 vs. 42.2 [p = 0.08]) [33]. The EQ-5D was the most utilized QOL scale (n = 5), followed by the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOLAD) scale (n = 2) and the SF-12 or Short Form Health Survey, 36 item (SF-36) (n = 3). Other QOL measures included the McGill QOL questionnaire, Cantril Ladder, and the Health Index. More information about these tools are presented in Table 4 [40,41,42,43,44,45].

3.1.2 Satisfaction with Care (SWC)

We found only one study explored the impact of deprescribing on patient- or designated representative-reported SWC, and it found no significant difference in those who were deprescribed statins versus usual care at 20 weeks (total n = 381; 4.63 vs. 4.55, area under the curve difference [95% CI] 0.08 [− 0.05 to 0.20]; p = 0.22) [30]. The population included those with limited life expectancy, as indicated by the surprise question (i.e., stating “would not be surprised if the patient died in the next year”) and recent deterioration in functional status. Approximately 48% had cancer. This study assessed satisfaction (“likelihood of recommending the current health care to others”) on a 5-item Likert scale (1, very unlikely to 5, very likely); both arms reported high satisfaction with their current healthcare. Satisfaction with deprescribing was not assessed specifically.

3.1.3 Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations

Four studies explored the impact of deprescribing on ED visits and hospitalizations; again, most found no difference [34, 37,38,39]. A total of 1066 enrolled participants were included in this outcome. All four studies occurred in different settings: hospital, community, a residential care facility, and nursing homes. Patient populations were high risk (including decompensated heart failure, frail, and previous fallers) [34, 37,38,39]. These four studies varied greatly in the medications targeted for deprescribing: including ‘non-beneficial’ medications (various), FRIDs, and β-blockers [34, 37,38,39]. Three of the four studies evaluated re-hospitalizations at 12 months and one assessed re-hospitalizations at 3 months after discontinuation. One non-randomized study of a single geriatric medical center found the patients’ annual referral rate to acute care facilities was 30% in the control group and 11.8% in the β-blocker deprescribed group (p < 0.002) at 12 months [38]; the remaining three studies found no difference in the rate of ED visits or hospitalizations.

3.2 Risk of Bias

Eight of the 12 included studies were RCTs [27, 28, 30, 32,33,34, 36, 37, 39]. Many RCTs (n = 8) were found to have a higher performance, detection, or other bias (Table 5). The four non-randomized trials included three feasibility studies and one non-randomized design divided based on physician assessment [29, 31, 35, 38]. These studies were found to have a higher bias due to confounding and classification of interventions (Table 6).

4 Discussion

In this systematic review, we sought to isolate the impact of deprescribing in older adults and older persons with life-limiting conditions on patient- or designated representative-reported QOL; SWC and ED visits and hospitalizations were also explored. We found that deprescribing was associated with a significant improvement in QOL in just two of ten studies, with the remaining eight studies finding no significant change between groups. Regarding patient- or designated representative-reported SWC and ED visits and hospitalizations, we also observed largely null effects in a much smaller group of studies.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review isolating the effect of deprescribing on QOL and these secondary outcomes in this patient group; however, similar results have been seen in other populations. A prior review by Dills et al. [46] evaluated the impact of deprescribing for chronic medical and mental health conditions managed in primary care in non-terminally ill patients aged 18 years and older and also found no improvement in QOL or negative events such as hospital admissions and falls. We focused our review on older adults and older persons with life-limiting conditions because they may have the greatest potential to benefit from deprescribing given a higher pill burden, higher risk of drug–drug interactions and adverse drug events, and greater use of medications with questionable benefit [47, 48].

There are several possible explanations for the heterogenous yet largely null effect of deprescribing on QOL we observed across studies. First, the impact of deprescribing on QOL may depend on the specific combination of medication(s) and patient population (inferred via clinical setting) targeted for deprescribing. Within this review, included studies deprescribed a diverse collection of medications, all with different potential risks and benefits. These studies also deprescribed within a variety of clinical settings. The only studies showing a positive effect of deprescribing on QOL included a large RCT of statin deprescribing in patients with less than 1 year of life expectancy and a small, non-randomized study of benzodiazepine deprescribing [30, 31]. It is possible these studies targeted appropriate medication and patient population combinations. For example, the study by Kutner and colleagues [30] excluded ambulatory patients receiving a statin for less than 3 months [30]. If this study had been conducted in the hospital, we may have seen different results. Previous literature suggests discontinuing statins within 3 months of a cerebrovascular event can negatively impact outcomes [49]. Patients who experience cerebrovascular events are often admitted to hospital for evaluation.

Secondly, patient preference may play an important role in the impact of deprescribing on QOL as well as SWC. In the two studies found to statistically improve QOL, patients were required to agree to withdrawing their statin or benzodiazepine in order to be included in the study [30, 31]. While a recent 2018 population-based survey study of US Medicare beneficiaries found 92% of participants are willing to stop taking one or more medications if their physician said it was possible, more research is needed to focus on which specific medication(s) patients would be willing to deprescribe [50]. To highlight this, a 2018 qualitative interview study inferred older adults are less likely to deprescribe their non-benzodiazepine medications, especially without another effective option to manage insomnia [51]. In this review patient preference was explored via SWC. Unfortunately, the only study assessing SWC found no difference between treatment groups. The study authors asked participants about the likelihood of recommending their current healthcare to others on a 5-point Likert scale, and found most had high satisfaction with their healthcare. Therefore, the lack of difference may have been due to the study’s supportive infrastructure overall. The study authors also chose a unique SWC measurement not specifically related to the deprescribing intervention itself [30].

Next, deprescribing is not without risk of ADWEs and it is possible that ADWEs may offset any positive effect of deprescribing due to reduced pill burden. For instance, Potter et al. [34] noted that 28 (8%, n = 348) of the deprescribed medications (which included a wide range of targeted agents) needed to be restarted after withdrawal was attempted due to an ADWE. Although subanalyses were not performed in this group, overall this study found no significant difference in QOL [34]. The presence of ADWEs may also explain the lack of difference found in ED visits and hospitalizations, as well as decreases in QOL scores from baseline found in three of the included studies [28, 33, 34].

These results also infer the timing of QOL measurement may be important. It is unclear if a patient’s QOL would improve shortly after a medication is removed, or if a longer duration of time is necessary to recognize the benefit of no longer being on that agent. The timing of a possible QOL benefit may also be medication or class specific, and may not be seen until after patients survive an initial period in which ADWEs are commonly experienced for a given drug. For example, expert opinion is to gradually taper benzodiazepines over 8–12 weeks as during this time there is a higher risk of ADWEs and withdrawal symptoms may persist for much longer in some patients [52]. In the study by Lopez-Peig et al. [31], the improvement in QOL after deprescribing benzodiazepines was seen at 24 months, but not earlier at 12 months. Accordingly, it is possible this study measured QOL at the appropriate time for benzodiazepine deprescribing.

In addition, it is unknown whether the heterogeneity in measurement tools used to assess QOL affected results. The most appropriate QOL instrument to measure the impact of deprescribing has not yet been identified or consistently utilized—the included studies utilized six different QOL instruments. To date, these tools have not been compared head-to-head in terms of sensitivity to change in response to deprescribing, and overall more data are needed to determine clinically significant and meaningful changes in scores [53, 54]. It may be important to measure the impact of deprescribing via a medication-focused QOL instrument such as the Medication-Related Quality of Life Scale (MRQoLS) rather than a general measure [55]. The MRQoLS was likely not included as it was validated and published in 2016 after many of the included studies were conducted.

Lastly, it is important to note a null effect may still be valuable in clinical practice. That is, if no change in outcomes (e.g., QOL or ED visits or hospitalizations) following deprescribing occurs, this could still be viewed as a positive outcome given a potential reduction in pill burden and costs [56]. Therefore, older adults’ health providers should continue to consider deprescribing potentially inappropriate or unnecessary medications in specific patient populations.

Findings from this review indicate a successful QOL-focused deprescribing intervention should include the following: an appropriate medication and patient population combination, preferably when the medication has reached its time until benefit and the patient is agreeable to deprescribing; the targeted medication is either tapered or a comprehensive monitoring plan is put into place to reduce the risk of ADWEs; QOL is measured via a validated, generally acceptable, feasible, and reliable medication-focused instrument and only when enough time has passed that the patient is able to recognize the benefit of no longer being on that agent; and, lastly, reasonable expectations are set with the patient (i.e., no change in QOL may also be beneficial and valuable).

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

We consider our exclusion criteria a major strength as we were able to isolate the effect of deprescribing on patient- or designated representative-reported QOL; to be included in this review the explicit act of deprescribing was required. We searched a number of databases from their inception to include all possible studies. We also implemented an evidence-based approach to assessing bias as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. While many included studies were found to have a higher performance or detection bias, this was also viewed as a strength; it may be important for patients to be aware a medication was deprescribed. Literature has suggested QOL benefits operate through awareness of reduced regimen complexity and pill burden [56]. The study by Bergh et al. [28], which utilized a placebo capsule for the discontinued medication instead of reducing pill burden, did not find a difference in QOL at 25 weeks.

This study was not without several limitations. Meta-analyses were not performed due to heterogeneity in study population, outcome measures, and methodological rigor of included studies. This heterogeneity prevented us from examining differential effects and underscores the need for additional studies examining deprescribing. Only published RCTs and non-randomized prospective studies were included to isolate the effect of deprescribing; retrospective analyses were excluded to reduce bias. QOL was a secondary outcome for many of included studies, suggesting they may not have been adequately powered to detect modest changes in QOL. Future studies should consider investigating the impact of deprescribing on functional status. This review did not focus on this outcome as we defined deprescribing as the systematic process of identifying and discontinuing medications within the context of an individual patient’s current level of functioning [9]. Previous conceptual models, however, have identified physical functioning as well as physical burden as important indicators for measuring medication-related QOL [57]. Lastly, although our comprehensive search included multiple strategies, three excluded studies involved languages other than English, therefore raising the possibility of language bias in our results.

5 Conclusion

Based on a limited number of studies with varying methodological rigor, patient populations, and medications targeted, deprescribing may not significantly improve patient- or designated representative-reported QOL or SWC; however, it also may not contribute to additional ED visits and hospitalizations. Future controlled studies are needed.

References

Saraf AA, Petersen AW, Simmons SF, et al. Medications associated with geriatric syndromes and their prevalence in older hospitalized adults discharged to skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:694–700.

Morin L, Laroche ML, Texier G, Johnell K. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults living in nursing homes: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(862):e1–9.

Redston MR, Hilmer SN, McLachlan AJ, Clough AJ, Gnjidic D. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older inpatients with and without cognitive impairment: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:1639–52.

Harrison SL, O’Donnell LK, et al. Associations between the Drug Burden Index, potentially inappropriate medications and quality of life in residential aged care. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:83–91.

Marcum ZA, Gellad WF. Medication adherence to multidrug regimens. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:287–300.

Pérez-Jover V, Mira JJ, Carratala-Munuera C, et al. Inappropriate use of medication by elderly, polymedicated, or multipathological patients with chronic diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):E310.

Eckerblad J, Theander K, Ekdahl A, et al. Symptom burden in community-dwelling older people with multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:1.

Deshields TL, Potter P, Olsen S, Liu J. The persistence of symptom burden: symptom experience and quality of life of cancer patients across one year. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1089–96.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:827–34.

Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, Hilmer SN. Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:303–19.

Pruskowski J, Handler SM. The DE-PHARM Project: a pharmacist-driven deprescribing initiative in a nursing facility. Consult Pharm. 2017;32:468–78.

Wouters H, Scheper J, Koning H, et al. Discontinuing inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:609–17.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793–807.

Stevenson J, Abernethy AP, Miller C, Currow DC. Managing comorbidities in patients at the end of life. BMJ. 2004;329:909–12.

Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, et al. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:34–41.

Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:583–623.

Bandayrel K, Johnston BC. Recent advances in patient and proxy-reported quality of life research. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:110.

Bladh L, Ottosson E, Karlsson J, Klintberg L, Wallerstedt SM. Effects of a clinical pharmacist service on health-related quality of life and prescribing of drugs: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:738–46.

Gallagher PF, O’Connor MN, O’Mahony D. Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:845–54.

Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, et al. Effects of pharmacists’ interventions on appropriateness of prescribing and evaluation of the instruments’ (MAI, STOPP and STARTs’) ability to predict hospitalization—analyses from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62401.

Spinewine A, Swine C, Dhillon S, et al. Effect of a collaborative approach on the quality of prescribing for geriatric inpatients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:658–65.

Van der Linden L, Decoutere L, Walgraeve K, et al. Combined use of the Rationalization of home medication by an Adjusted STOPP in older Patients (RASP) list and a pharmacist-led medication review in very old inpatients: impact on quality of prescribing and clinical outcome. Drugs Aging. 2017;34:123–33.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research; Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, et al., editors. Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011. https://doi.org/10.17226/13059. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209518/. Accessed 23 Sept 2019.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–94.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

Beer C, Loh PK, Peng YG, Potter K, Millar A. A pilot randomized controlled trial of deprescribing. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2:37–43.

Bergh S, Selbæk G, Engedal K. Discontinuation of antidepressants in people with dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms (DESEP study): double blind, randomised, parallel group, placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e1566.

Bourgeois J, Elseviers MM, Van Bortel L, Petrovic M, Vander Stichele RH. Feasibility of discontinuing chronic benzodiazepine use in nursing home residents: a pilot study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(10):1251–60.

Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH Jr, et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:691–700.

Lopez-Peig C, Mundet X, Casabella B, del Val JL, Lacasta D, Diogene E. Analysis of benzodiazepine withdrawal program managed by primary care nurses in Spain. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:684.

Moonen JE, Foster-Dingley JC, de Ruijter W, et al. Effect of discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment in elderly people on cognitive functioning—the DANTE Study Leiden: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1622–30.

Polinder S, Boyé ND, Mattace-Raso FU, et al. Cost-utility of medication withdrawal in older fallers: results from the Improving Medication Prescribing to reduce Risk Of FALLs (IMPROveFALL) trial. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:179.

Potter K, Flicker L, Page A, Etherton-Beer C. Deprescribing in frail older people: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149984.

Sakakibara M, Igarashi A, Takase Y, Kamei H, Nabeshima T. Effects of prescription drug reduction on quality of life in community-dwelling patients with dementia. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18:705–12.

Ulfvarson J, Adami J, Wredling R, Kjellman B, Reilly M, von Bahr C. Controlled withdrawal of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor drugs in elderly patients in nursing homes with no indication of depression. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:735–40.

Boyé ND, van der Velde N, de Vries OJ, et al. Effectiveness of medication withdrawal in older fallers: results from the Improving Medication Prescribing to reduce Risk Of FALLs (IMPROveFALL) trial. Age Ageing. 2017;46:142–6.

Garfinkel D, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9:430–4.

Jondeau G, Neuder Y, Eicher JC, et al. B-CONVINCED: beta-blocker CONtinuation vs. INterruption in patients with Congestive heart failure hospitalizED for a decompensation episode. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2186–92.

Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1965.

Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33:337–43.

Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995;9:207–19.

Torisson G, Stavenow L, Minthon L, Londos E. Reliability, validity and clinical correlates of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s disease (QoL-AD) scale in medical inpatients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:90.

Hagell P, Westergren A, Årestedt K. Beware of the origin of numbers: standard scoring of the SF-12 and SF-36 summary measures distorts measurement and score interpretations. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40:378–86.

Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312116671725. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312116671725.

Dills H, Shah K, Messinger-Rapport B, Bradford K, Syed Q. Deprescribing medications for chronic diseases management in primary care settings: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(923–935):e2.

Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in the elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57–65.

Bain KT, Holmes HM, Beers MH, Maio V, Handler SM, Pauker SG. Discontinuing medications: a novel approach for revising the prescribing stage of the medication-use process. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1946–52.

Lee M, Saver JL, Wu YL, et al. Utilization of statins beyond the initial period after stroke and 1-year risk of recurrent stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005658.

Reeve E, Wolff JL, Skehan M, Bayliss EA, Hilmer SN, Boyd CM. Assessment of attitudes towards deprescribing in older Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1673–80.

Kuntz J, Kouch L, Christian D, Peterson PL, Gruss I. Barriers and facilitators to the deprescribing of nonbenzodiazepine sedative medications among older adults. Perm J. 2018;22:17–157.

Dou C, Rebane J, Bardal S. Intervention to improve benzodiazepine tapering success in the elderly: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2018;16:1–6.

Payakachat N, Ali MM, Tilford JM. Can the EQ-5D detect meaningful change? A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:1137–54.

Glasziou P, Alexander J, Beller E, Clarke P. Which health-related quality of life score? A comparison of alternative utility measures in patients with type 2 diabetes in the ADVANCE trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:21.

Tseng HM, Lee CH, Chen YJ, Hsu HH, Huang LY, Huang JL. Developing a measure of medication-related quality of life for people with polypharmacy. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1295–302.

Thompson W, Reeve E, Moriarty F, et al. Deprescribing: future directions for research. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15:801–5.

Mohammed MA, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Pharmaceutical care and health related quality of life outcomes over the past 25 years: have we measured dimensions that really matter? Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:3–14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jennifer A. Pruskowski, Carolyn T. Thorpe, Michele Klein-Fedyshin, and Steven M. Handler declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Sydney Springer’s work on this project was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affairs Fellowship in Medicare Safety & Pharmacy Outcomes. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding

The authors received no funding support for this work or to assist in the preparation of this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pruskowski, J.A., Springer, S., Thorpe, C.T. et al. Does Deprescribing Improve Quality of Life? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Drugs Aging 36, 1097–1110 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00717-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00717-1