Abstract

Background and Objective

Psychotropic drug use is high in nursing homes in Belgium. A practice improvement initiative (including education, professional support and the transition towards person-centred care) achieved significant reductions in psychotropic drug use. The initiative outline was transcribed into a general intervention template, and consequently implemented in five nursing homes (in mixed locations and with a mixed character) in preparation for a future broader roll-out in Belgium. The impact of the intervention on the use of psychotropic drugs in these five nursing homes is reported in this paper.

Methods

The general intervention template was fitted into the individual nursing home setting. Education for the nursing home personnel on psychotropic drugs and non-pharmacological alternatives, as well as details for a transition to person-centred care was provided. Psychotropic drug use was recorded using a dynamic cohort study design with cross-sectional observations (November 2016–November 2017).

Results

At baseline, participants’ (n = 677) mean age was 85.6 years (range 54–109 years), with 72.6% female. Mean medication intake was 8.5 (range 1–22), predominantly central nervous system drugs (Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical classification N, 88.8%). Long-term (> 3 months) psychotropic drug use (62.0%) and concomitant psychotropic drug use (31.5% taking two or more medications) were high. After 12 months, the prevalence of long-term psychotropic drug use decreased significantly (from 62.0 to 52.9%, p < 0.001), likewise the combined use of psychotropic drugs (from 31.5 to 24.0%, p = 0.001). The decrease in the prevalence of antidepressant and hypnosedative use was significant (respectively, from 32.2 to 23.4%, p < 0.001, and from 35.3 to 28.7%, p = 0.006) in contrast to antipsychotic use (from 17.1 to 15.9%, p = 0.522).

Conclusions

The stand-alone adaptation of the previously reported initiative using a general template was possible. This intervention resulted in a significant decrease in psychotropic drug use (predominantly hypnosedatives and antidepressants) among nursing home residents after 12 months.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The use of psychotropic medications (hypnosedatives, antidepressants and antipsychotics) remains high among nursing home residents in Belgium, despite diverse campaigns to reduce use. |

An earlier initiative proved successful in reducing the use of psychotropic drugs. The main elements in this initiative are education, professional support for nursing home residents, involving every member of the nursing home personnel, and predominantly the transition towards person-centred care. The previous intervention was recorded on a template, and tested for implementation in five nursing homes. |

The implementation of the intervention, and the adaptation to an individual nursing home setting was possible. Overall, the intervention proved again to successfully reduce the prevalence of psychotropic drug use, predominantly for hypnosedatives and antidepressants, but not for antipsychotics. |

1 Introduction

Nursing home residents are amongst those with the highest level of multimorbidity, care dependency and the highest medication intake [1]. A high medication intake often includes high use of psychotropic medications (e.g. hypnosedatives, antidepressants and antipsychotics) [2]. These are often prescribed because of the higher prevalence of sleeping problems and/or mental disorders, in particular dementia and related behavioural and psychological symptoms [3,4,5].

Psychotropic medications are indicated in a limited number of cases, i.e. only when a non-pharmacological approach seems insufficient, and only as a well-tailored, monitored and time-limited therapy [6]. The reality is that these drugs are often prescribed, often mutually combined and often on a long-term basis without reassessment of the appropriateness [7, 8]. Specific for the nursing home setting, the quality of psychotropic drug prescribing is influenced by extreme frailty and care dependency of the residents, a limited physician’s presence on the floor, nurses’ influence on the choice of pharmacotherapy, and limited staff and knowledge of geriatric pharmacotherapy [9].

The prevalence of psychotropic drug use is high in Belgium, and especially high in Belgian nursing homes [2, 10,11,12]. Recently, a practice improvement initiative (“Towards an effective and efficient use of psychotropic drugs”, the Leiehome project) was initiated in a nursing home in Flanders, Belgium aiming to reduce high in-house psychotropic drug use [13]. The initiative started with educational sessions related to respective psychotropic drug classes (i.e. hypnosedatives, antipsychotics and antidepressants), which were offered to the complete nursing home staff (including nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and logistic personnel). Subsequently, the focus was put on the transition to patient-centred care through professional support including offering a variety of meaningful activities to the nursing home residents [14]. For every current prescribed psychotropic drug, the original indication for the prescription was reassessed, as well as exploration of current options for a discontinuation. For every potential new prescription for a psychotropic drug, the indication was cautiously assessed, and the possibility of adding an end date for the treatment was always discussed [13].This resulted in an overall reduction in psychotropic drug use from 72 to 62%, in hypnosedative use by 20% and antidepressant use by 17% over the period of 12 months.

The positive effect of this nursing home initiative led to funding from the Flemish Government for an implementation study with the aim to amend the original intervention to a template for a future roll-out. The aim of this study was to investigate whether the intervention, starting from a general intervention template, could be successfully implemented in separate nursing homes, resulting in a decreased prevalence of psychotropic drug users (hypnosedatives, antidepressants and antipsychotics).

2 Methods

This implementation study was tested in five nursing homes with a mixed character (private to public) over a follow-up period of 12 months.

2.1 Design

For this study, the outlines from the earlier practice improvement initiative “Towards an effective and efficient use of psychotropic drugs” in a nursing home in Flanders, Belgium were used [13]. This initiative has resulted in a significant reduction in the prevalence of long-term psychotropic drug users (predominantly hypnosedatives and antidepressants) [13]. As a result of the significant reductions and positive experiences during this initiative, it was decided to perform an implementation study for a potential future roll-out.

An implementation study was performed using a dynamic, prospective cohort study design, with an observation period over the course of 12 months. The dynamic cohort implies that this study is examining the psychotropic medication intake of the nursing home population as cross-sectional observations. As the initial initiative demonstrated significant improvement, no control group was assigned in this study.

2.2 Eligibility Criteria

The study was conducted in five nursing homes, which reflect the diversity in character (public or private setting), and region (urban, rural) of nursing homes in Flanders. To be eligible, the nursing homes needed the following: (1) at least two-thirds of all general practitioners (GPs) agreeing to participate; (2) assignment of an internal project leader (0.2 full-time equivalent [FTE]); and (3) an electronic system for the organisation of the medication charts.

2.3 Intervention

The protocol of the earlier practice improvement initiative was used, to set the outlines of intervention into a general intervention template [13]. From now on, the wording intervention to describe the translation of the earlier initiative is maintained.

The template was printed out and given to the nursing homes, but was also reviewable online. It provided extensive information on what to perform, for whom, at what stage, and using what materials. It provided supporting material and instructions for each phase in the intervention (e.g. background information on the educational sessions, delineation of non-pharmacological alternatives). Furthermore, all available documents from the first study (e.g. brochures, flyers) were distributed and stored online.

The participating nursing homes could adapt these instructions to best fit their own nursing home setting, to achieve an optimal implementation of the intervention. This was supervised by an internal project leader (0.2 FTE). During the preparation and information phase, a collaborator from the first practice improvement initiative [13] could be contacted for additional information and support by all the nursing homes.

A preparation and information phase (August 2016–October 2016) preceded the intervention period to inform the nursing home director, coordinating physician, treating GPs and pharmacist on the next steps, and to assign team leaders responsible for the implementation of the intervention. The realisation of the intervention (November 2016–November 2017) consisted of a transition to person-centred care, supported by education, medication assessment and judicious deprescribing.

2.3.1 Aspects of the Intervention

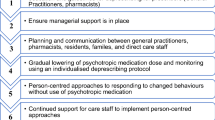

Figure 1 provides the flow of the intervention. An overview of the intervention is given in Box 1.

The first aspect in the template was to hold educational sessions for GPs and the nursing personnel separately. Each session dealt with a particular topic (sleeping problems, depression in old age, challenging behaviour) related to the prescribing of a psychotropic drug. The content of the courses was focused on evidence-based practice, reductions in psychotropic drug use (including specific guidance on how to deprescribe) and non-pharmacological alternatives. The educational sessions were held at different time periods so that most of the nursing home personnel could attend. The educational sessions were recorded and made available online.

The thorough medication assessment for all residents by the GP, driven by the nurse was the next step of the intervention. For all psychotropic drugs (long term and as needed), the nurse investigated the duration of the therapy; the original indication for treatment was assessed and reviewed whether it was still present. Afterwards, the GP was contacted by the nurse to review the psychotropic medication. In agreement with the nursing home resident and/or their relatives, it was reviewed whether discontinuation was possible or whether the dose or duration could be lowered. The main aspect during the whole intervention was the transition towards person-centred care. The individual’s needs, history and values as well as the desired health outcome of a patient were heard and the care was tailored accordingly.

The transition towards person-centred care was considered key in the execution of the intervention. It was facilitated by an awareness campaign for all personnel (healthcare professionals, logistics, cleaning staff) and all nursing home residents. Brochures were given to the patients and their relatives, and flyers were displayed throughout the nursing homes.

Nurses had a leading role in the intervention, owing to their data collection, daily contacts with residents and their contacts with GPs to motivate them for the intervention. However, for all personnel, multidisciplinary meetings were encouraged to ensure a positive working attitude.

Together with the potential deprescribing of psychotropic drugs, it was reviewed how non-pharmacological alternatives could aid the deprescribing process for each individual resident (for instance, music or aroma therapy). Instead of psychotropic drugs, other alternatives (including meaningful activities) were tailored to the resident (e.g. offering a warm glass of milk in the evening instead of a hypnosedative, or placing a ribbon in an open doorway to halt wandering behaviour to other rooms) [14].

Box 1. Overview of the intervention

Educational courses | |

|---|---|

Topic | Explanation |

Sleeping problems | Physiological changes in the sleeping pattern of older adults Causes of insomnia and causal interventions Risks and benefits of hypnosedatives Non-pharmacological interventions: effectiveness, practical application |

Old age depression | Detecting depression and depressive symptoms Interventions (basic, psychotherapy, handling rebound depression) Risks and benefits of antidepressants Non-pharmacological interventions: effectiveness, practical application |

Challenging behaviour | Differentiating BPSD and other challenging behaviour Prevention, watchful waiting or specific interventions? Risks and benefits of anti-psychotics Non-pharmacological interventions: effectiveness, practical application |

Transition to person-centred care | |

|---|---|

Actions | Questions/tasks |

Assessment of psychotropic drug intake by nurses | How many? Which? |

Assessment of indications for prescribing psychotropic drugs | Is the indication still present? |

Beliefs and wishes of patient and family regarding psychotropic drugs | On what ground did the patient want a pharmacological treatment? Is discontinuation an option? |

Evaluation of psychotropic drug intake | Was it effective? Did it affect the resident negatively (worsening BPSD, depressive behaviour …?) Was there a dose reduction in the past? Was it effective? |

Involvement of the patient and his/her family | Education, explaining risks and benefits, understanding beliefs of residents |

Observation and reporting of behavioural changes, and linking back to medication intake | How do the residents cope with discontinuation of psychotropic drugs? Frequent observation of non-verbal signals in the case of patients with dementia Report behaviour in an objective manner |

Organise multidisciplinary meetings | Describe changes in behaviour, hold reflection moments. Repeat the educational sessions. Search as a team for the most suitable non-pharmacological approach for one resident. Interact with volunteers |

2.4 Data Collection and Data Processing

Data were collected for all residents from their medical records and electronic medication administration charts at fixed time points in the observation period. Data included personal characteristics (date of birth, sex) and medication data.

Functional characteristics included cognitive status (scored by the Mini-Mental State Examination, range 0–30 with 0 indicating severe cognitive impairment), activities of daily living (scored by Katz Activities of Daily Living, Activities of Daily Living scale, range 6–24 with 6 indicating complete care independent), and disorientation in time and place (scored by the Katz score, range 0–8 with 8 corresponding with complete disorientation in time and place). The use of the Katz disorientation scale is mandatory in nursing homes in Belgium and is easy for nurses and nursing assistants to complete. It is an index applied by means of an interview and observation, equally valid in assessing disorientation in time and place in patients with and without dementia. High-care dependency was defined as a score above 17 on the Katz Activities of Daily Living, dementia symptoms were defined as scores above 5 on the Katz disorientation scale.

Medication data included all prescribed medications, long term, short term or as needed. The medications were coded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification (World Health Organization ATC/DDD 2013) using a data program based on the official register of medications available on the Belgian market. Focus was on psychotropic medications (ATC pharmacological subgroups N05A, N06A and N05BA-N05CD-N05CF, i.e. antipsychotics, antidepressants and hypnosedatives, respectively). Polypharmacy was defined as the long-term use of five or more medications. Long-term use was defined as use longer than 3 months (i.e. 90 daily defined doses). Combination therapy was defined as the use of two or more psychotropic drugs, or a combined use within therapeutic subgroups.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

We encountered no missing data. Administrative data were collected from the nursing home systems, and medication data could be retrieved from the medication administration chart at any time.

SPSS 23.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. For the descriptive statistics, means, medians or proportions were used. We performed a comparison of continuous data using t tests or non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon and Kruskal–Wallis tests) in the case of skewed data. Analysis of categorical variables was performed using Chi squared tests.

The main endpoint was the prevalence of psychotropic drug users. For this study, only the baseline and final time point were compared within this dynamic cohort. The paired analysis was performed in a closed cohort, including the residents present at both baseline and at the end of the study. All drug use at baseline and at the end of the study for each patient was paired and compared with paired analysis techniques.

2.6 Ethics Approval

The original intervention received funding from the Fund for Addictions (Fonds voor Verslavingen in Dutch) from the Federal Public Service for Health, Food Chain Safety, and Environment. Given the positive results, a new proposal was submitted. Funding was received from the Flemish Agency for Care and Health (Vlaams Agentschap voor Zorg en Gezondheid in Dutch) with the aim to test the potential roll-out of the intervention across nursing homes.

An approval was granted by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Gent University Hospital (B670201420698). Permission was given by the board of directors and the supervising physician of each participating nursing home. All data were codified and anonymised.

3 Results

3.1 Description of the Nursing Homes and their Residents

There were three private and two public nursing homes (designated NH 1–5), two were located in a rural region, one in a suburban region and two in an urban region. The number of beds ranged between 104 and 177. The number of nurses and nursing assistants (expressed in FTE) ranged between 11.0 and 14.9.

In total, 677 residents participated across the five participating nursing homes. Their mean age was 85.6 years (range 54–109 years), with 72.6% female. The populations in the different nursing homes varied; the level of complete care dependency and/or disorientation ranged between 37.4% (NH 4) and 61.6% (NH 1). For a full background and overview of the nursing homes and the residents’ characteristics, see Table 1.

3.2 Description of the Drug Use at Baseline

The mean number of drugs per patient used at baseline was 8.5 drugs (range 1–22), predominantly for long-term use (7.2, range 0–19). There was a mean number of ‘as-needed use’ of 1.1 (range 0–12). The mean number of drugs varied between 6.9 and 9.8 across nursing homes. For a full comparison on the mean total and mean long-term medication intake across the nursing homes, see Fig. 2.

At the main anatomical ATC level, nervous system drugs were predominantly consumed by the patients (89% of patients taking a nervous system drug, e.g. analgesics and psychotropic drugs), followed by alimentary drugs (e.g. vitamins, anti-diabetic medications) and cardiovascular medications (e.g. statins, beta-blockers). For a full overview of the drug use, and all main anatomical ATC classes, see Table 2.

The prevalence of long-term psychotropic drug users at baseline was 62.0%, with a mean psychotropic drug use of 1.4 (range 0–7). Combined use of two or more psychotropic drugs was present in 31.5% of the population. The prevalence of long-term antidepressant users was 35.3% (range 0–3), 32.2% (range 0–4) for long-term hypnosedative users and 17.1% (range 0–3) for long-term antipsychotic users.

3.3 Effect of the Intervention between Baseline and the End of the Study

There was a significant decrease in the mean number of medications used (from 8.5 to 7.2, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.001) at the end of the follow-up period (after 12 months). The mean number of long-term and as-needed medications dropped significantly (respectively from 7.2 to 6.2; p < 0.001 and from 1.1 to 0.9; p = 0.014). The prevalence of residents with polypharmacy (long-term intake of five or more medications) dropped significantly from 76.8% to 67.6% (p < 0.001).

In addition, there was a noticeable shift in the prevalence of older adults with concomitant use of long-term and as-needed psychotropic medications. The prevalence of older adults with multiple medications decreased significantly (from 31.5% to 24.0%, p = 0.001), and the prevalence of older adults with no psychotropic drugs increased significantly. The prevalence of nursing home residents with no psychotropic drugs increased from 38.0% to 47.1% (p > 0.001). For a full overview of the concomitant use of psychotropic drugs, see Fig. 3.

At the end of the follow-up, the overall psychotropic drug user prevalence decreased significantly from 62.0 to 52.9% (p < 0.001). The effect was most noticeable in the prevalence of hypnosedatives and antidepressants. The prevalence of hypnosedative users dropped significantly from 32.2 to 23.4% (p < 0.001) and the prevalence of antidepressant users dropped significantly from 35.3 to 28.7% (p = 0.006). There was no significant decrease in the prevalence of antipsychotic users (from 17.1 to 15.9%, p = 0.522). An overview of the evolution in prevalence of psychotropic drug users can be seen in Fig. 4.

Table 3 provides the results of the paired analyses per nursing home. The overall prevalence of psychotropic drug users decreased significantly in NH 1, NH 3 and NH 4. At the different subclasses, the prevalence of hypnosedative users decreased significantly only in NH 1. The prevalence of antidepressant users decreased significantly in NH 1 and NH 3.

4 Discussion

In this study, we described the implementation of an earlier successful practice improvement initiative in five nursing homes as preparation for a future broader roll-out [13]. The initiative was transcribed into a general intervention template, denoting every aspect so that a participating nursing home could employ the template to best fit its own nursing home setting. Central in the intervention was the transition towards a more person-centred approach (how can we help an individual patient best to discontinue his/her psychotropic drugs?), supported by educational sessions and professional support. The intervention resulted in a significant decrease in psychotropic drug use.

The main findings include an overall and significant decrease of 9.1% in the prevalence of long-term psychotropic drug users over the period of 12 months. The prevalence of patients with combined use of psychotropic drugs decreased as well, the prevalence of nursing home residents with three or more psychotropic drugs dropped by 9.5%. The changes were most noticeable in the prevalence of hypnosedative and antidepressant users with significant decreases by 8.8% and 6.6%, respectively, over the period of 12 months.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

This study provides evidence to add to the growing body of knowledge that suggests a multidisciplinary approach can lead to significant decreases in overall psychotropic drug use, predominantly in the prevalence of hypnosedative and antidepressant users. The gradual but continuous longitudinal change in the positive attitudes of nursing home personnel was key for this intervention. The intervention had a sustained effect over the 1-year study period in a realistic and dynamic sample of nursing home residents. The transcription into a general intervention template ensured a higher transferability, yet we did not conduct a process evaluation for the implementation of the intervention, nor did we perform a qualitative exploration of the experience of nurses, personnel and nursing home residents.

The main limitations of this implementation study were the small number of nursing homes and the lack of a control group. In the present study, a dynamic cohort with repeated cross-sectional observations was used, taking into account newly admitted nursing home residents. The outlines of an earlier practice improvement initiative (which has demonstrated significant results) were used, omitting the need for a control group. Yet, without a control group and without assessing other confounding variables, we are not able to determine if the discontinuation of psychotropic drugs was influenced by factors other than the intervention.

Another limitation was a potential ascertainment bias, meaning that the most eager nursing home might have volunteered to participate. The main outcome of this study was the prevalence of psychotropic drug users. Other patient-reported outcome measures (e.g. quality of life, mortality) were not assessed. The study team was also unable to assess dosage reductions in a standardised manner.

4.2 Relationships to Other Findings

4.2.1 Psychotropic Drug Use Remains High in Belgium

Our study confirmed the high drug use among nursing home residents in Flanders, Belgium [2], predominantly the high use of central nervous system, cardiovascular and alimentary medications [15]. In comparison with findings from the Prescribing in Homes for the Elderly in BElgium (PHEBE, 2006) study, the prevalence of psychotropic drug use has decreased [10]. The prevalence of psychotropic drug use is similar to other recent research in nursing homes in Belgium, albeit there was a higher hypnosedative and antidepressant use and a lower antipsychotic use in the present study [2].

4.2.2 As-needed Psychotropic Drugs are Often Given Long Term

Psychotropic drugs are commonly prescribed, yet often without an appropriate indication [16, 17]. In the PROPER I-study, it is claimed that around 10% of all psychotropic drugs prescribed for nursing home residents with dementia are appropriate (in terms of indication and duration) [18]. However, it is only recently been highlighted that psychotropic drugs are often underestimated in studies owing to the hidden nature of ‘as-needed’ medications [19]. Studies often focus solely on long-term medications, yet psychotropic drugs can also be prescribed as needed only (or pro re nata) but actually given on a regular basis for a long period of time. In this study, a high prevalence of as-needed medication was noted at the start, but a decrease occurred. We carefully controlled changes in the medication prescriptions to review if a transition from long-term use to as needed took place, but no substitution to as-needed medications at the end of the observation period was observed.

4.2.3 Interventions Affect Hypnosedatives and Anti-Depressants, but not Antipsychotics

Nurses and nursing assistants face a high workload in the care of nursing home residents. Neuropsychiatric symptoms common in residents with dementia pose serious challenges to the nursing home staff [20], potentially compromising effective care. Nursing home personnel might have concerns about relapsing or worsening symptoms, and the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms when deprescribing psychotropic drugs [21], but earlier findings suggest that a discontinuation of antipsychotics can be achieved in the majority of patients without major effects on dementia-related behavioural and psychological symptoms. Antipsychotics in patients with severe symptoms at baseline might however be more difficult to withdraw [22,23,24]. However, it must be remembered that the choice between antipsychotics or use of a physical restraint is not easy to make.

The evidence on reducing psychotropic drugs in nursing home residents through various interventions is still limited and not consistent [25]. In a French study, audits and interdisciplinary team meetings did not result in significant changes in the prevalence of benzodiazepine users (n = 3973), potentially owing to external factors affecting the intervention [26].

Both in the present and previous study, we observed that the discontinuation of antipsychotics was not successful. The RedUSe (Reducing Use of Sedatives) trial assessed the impact of a multi-strategic interdisciplinary intervention on antipsychotic and benzodiazepine prescribing in Australian residential aged care facilities. The authors reported a reduction in the prevalence of antipsychotic and benzodiazepine users, and also in dose reductions [27,28,29]. The intervention in RedUSe consisted of an audit and feedback, staff education, an interdisciplinary review and a prominent role for a nurse [27]. The RedUSe trial reported a lower prevalence of hypnosedative users, yet a higher baseline prevalence of antipsychotic users than in our study. The lower prevalence of antipsychotic use in Belgium may have been the result of efforts made since the publication of the PHEBE study in Belgium (2006) [10]. The prevalence of antipsychotic use has decreased by more than 10%.

Discontinuation of antipsychotics can be hampered because of relapsing behavioural or psychological problems. There are often barriers, expressed by family as well as healthcare professionals (e.g. fear of returning aggressive behaviour by family members, fear of higher workload in patients with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia).

The absolute decrease of 9.1% in long-term psychotropic drug use can be considered a success. The decrease could have had a broader effect than measured in this study. For instance, for nursing personnel, it could have provided proof that non-pharmacological methods can be tailored to a patient and that they can be effective. For patients, the intervention could have led to clinically significant changes (e.g. improvements in alertness). From a health-economic perspective, a net saving in pharmacological costs can be expected.

4.2.4 Culture Within a Nursing Home as a Determinant

In our study, the intervention did not yield significant reductions for all classes in the separate nursing homes, potentially owing to the differences in nursing home populations (varying level of care dependency and disorientation) and the number of nursing staff, or possibly because of differences in staff knowledge and motivation. It has been suggested that a high prevalence of psychotropic drug use is not clearly associated with nursing home characteristics, but rather with the ‘culture’ within a nursing home [12, 30, 31]. A transition towards a culture where non-pharmacological alternatives are first considered is not easily implemented, considering existing limitations [32] and considering limited evidence [33, 34]. One of the perceived key points contributing to the success of this intervention was the inclusion of residents [35], their relatives and family [36], as well as all nursing home personnel, logistics staff, cleaning personnel and nursing home board of direction. Future research could focus on the contributing role of nursing home resident characteristics and the characteristics of the nursing home (and employees) towards the success or failure of implementing similar initiatives.

4.2.5 Need for Further Broader Strategies

In a cohort of newly admitted nursing home residents in Flanders, Belgium, high antipsychotic use was noted. In these nursing home residents, signs of deprescribing for hypnosedatives and antidepressants were noticed after 2 years in residents with poor physical and mental health, but not for antipsychotics [2]. The fact that nursing home residents often arrive in the nursing home with several psychotropic drugs already prescribed underlines the need for broader preventive strategies that are not solely embedded within the long-term care setting [17].

The high number of psychotropic drugs might be a consequence of inadequate strategies, either as a result of economic considerations or in-house attitudes towards psychotropic medications [30]. In Belgium, for instance, the cost of psychotropic medications is covered either by the nursing home residents or health insurance, but offering non-pharmacological alternatives is at the expense of the nursing home. More research may be needed to identify potential facilitators and barriers among nursing home personnel and residents when changing to person-centred care.

In this study, the hiring of an internal project leader (0.2 FTE) was made possible by the funding received by the Flemish Government. In a later phase, project leaders need to be trained and assigned to nursing homes to guide the implementation. However, it must be reviewed if training and assigning extra personnel is cost effective, and if the intervention can lead to lowered healthcare usage (fewer falls, fewer GP visits, reduced medication costs).

5 Conclusions

An earlier practice improvement initiative was transcribed into a general intervention template. The intervention was implemented in five nursing homes in Flanders, Belgium. The combination of education, professional support and the transition towards patient-centred care proved successful in the discontinuation of high in-house psychotropic drug use. There was an overall significant reduction in total psychotropic drug use, combined use of psychotropic drugs, and total hypnosedative and antidepressant use, but not in the use of antipsychotics.

References

Schüssler S, Dassen T, Lohrmann C. Care dependency and nursing care problems in nursing home residents with and without dementia: a cross-sectional study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28:973–82.

Ivanova I, Wauters M, Stichele RV, Christiaens T, De Wolf J, Dilles T, et al. Medication use in a cohort of newly admitted nursing home residents (Ageing@NH) in relation to evolving physical and mental health. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;75:202–8.

Mann E, Köpke S, Haastert B, Pitkälä K, Meyer G, Alanen H, et al. Psychotropic medication use among nursing home residents in Austria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:18.

Hollingworth SA, Siskind DJ, Nissen LM, Robinson M, Hall WD. Patterns of antipsychotic medication use in Australia 2002–2007. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44:372–7.

Sterke CS, van Beeck EF, van der Velde N, Ziere G, Petrovic M, Looman CWN, et al. New insights: dose-response relationship between psychotropic drugs and falls: a study in nursing home residents with dementia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:947–55.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2018.

Barnes TRE, Banerjee S, Collins N, Treloar A, McIntyre SM, Paton C. Antipsychotics in dementia: prevalence and quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in UK mental health services. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:221–6.

Selbæk G, Kirkevold Ø, Engedal K. The course of psychiatric and behavioral symptoms and the use of psychotropic medication in patients with dementia in Norwegian nursing homes: a 12-month follow-up study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:528–36.

Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47:533–43.

Azermai M, Elseviers M, Petrovic M, Van Bortel L, Vander Stichele R. Geriatric drug utilisation of psychotropics in Belgian nursing homes. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2011;26:12–20.

Elseviers MM, Vander Stichele RR, Van Bortel L. Quality of prescribing in Belgian nursing homes: an electronic assessment of the medication chart. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:93–9.

Anrys PMS, Strauven GC, Foulon V, Degryse J-M, Henrard S, Spinewine A. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in Belgian nursing homes: prevalence and associated factors. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:884–90.

Azermai M, Wauters M, De Meester D, Renson L, Pauwels D, Peeters L, et al. A quality improvement initiative on the use of psychotropic drugs in nursing homes in Flanders. Acta Clin Belg. 2017;72:163–71.

De Vriendt P, Cornelis E, Vanbosseghem R, Desmet V, Van de Velde D. Enabling meaningful activities and quality of life in long-term care facilities: the stepwise development of a participatory client-centred approach in Flanders. Br J Occup Ther. 2019;82(1):15–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022618775880.

Linjakumpu T, Hartikainen S, Klaukka T, Veijola J, Kivelä S-L, Isoaho R. Use of medications and polypharmacy are increasing among the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:809–17.

Stevenson DG, Decker SL, Dwyer LL, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC, Metzger ED, et al. Antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use among nursing home residents: findings from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:1078–92.

Stock KJ, Amuah JE, Lapane KL, Hogan DB, Maxwell CJ. Prevalence of, and resident and facility characteristics associated with antipsychotic use in assisted living vs. long-term care facilities: a cross-sectional analysis from Alberta, Canada. Drugs Aging. 2017;34:39–53.

van der Spek K, Gerritsen DL, Smalbrugge M, Nelissen-Vrancken MHJMG, Wetzels RB, Smeets CHW, et al. Only 10% of the psychotropic drug use for neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia is fully appropriate: the PROPER I-study. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2016;28:1589–95.

Allers K, Dörks M, Schmiemann G, Hoffmann F. Antipsychotic drug use in nursing home residents with and without dementia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32:213–8.

MacPherson S, Davison TE, Hallford D, Mellor D, Seedy M, Bird M, et al. Behavioral symptoms of dementia that present management difficulties in nursing homes: staff perceptions and their concordance with informant scales. J Gerontol Nurs. 2016;43:34–43.

Tjia J, Lemay CA, Bonner A, Compher C, Paice K, Field T, et al. Informed family member involvement to improve the quality of dementia care in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:59–65.

Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, Vander Stichele R, De Sutter AI, van Driel ML, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD007726.

Van Leeuwen E, Petrovic M, van Driel ML, De Sutter AI, Vander Stichele R, Declercq T, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of long-term antipsychotic drug use for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD007726.

Van Leeuwen E, Petrovic M, van Driel ML, De Sutter AI, Stichele R Vander, Declercq T, et al. Discontinuation of long-term antipsychotic drug use for behavioral and psychological symptoms in older adults aged 65 years and older with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:1009–14.

Gould RL, Coulson MC, Patel N, Highton-Williamson E, Howard RJ. Interventions for reducing benzodiazepine use in older people: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:98–107.

de Souto Barreto P, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Cestac P, Vellas B, Rolland Y. Effects of a geriatric intervention aiming to improve quality care in nursing homes on benzodiazepine use and discontinuation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81:759–67.

Westbury J, Jackson S, Gee P, Peterson G. An effective approach to decrease antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use in nursing homes: the RedUSe project. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:26–36.

Westbury J, Tichelaar L, Peterson G, Gee P, Jackson S. A 12-month follow-up study of “RedUSe”: a trial aimed at reducing antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use in nursing homes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:1260–9.

Westbury JL, Gee P, Ling T, Brown DT, Franks KH, Bindoff I, et al. RedUSe: reducing antipsychotic and benzodiazepine prescribing in residential aged care facilities. Med J Aust. 2018;208:398–403.

Richter T, Mann E, Meyer G, Haastert B, Köpke S. Prevalence of psychotropic medication use among German and Austrian nursing home residents: a comparison of 3 cohorts. J Am Med. Dir Assoc. 2012;13(187):e7–13.

Hughes CM, Lapane K, Watson MC, Davies HTO. Does organisational culture influence prescribing in care homes for older people? A new direction for research. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:81–93.

Leten L, Azermai M, Wauters M, De Lepeleire J. Een kwalitatieve exploratie van het chronisch gebruik van psychofarmaca in woonzorgcentraA qualitative exploration of the chronic use of psychotropic drugs in nursing homes. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;48:177–86.

Cabrera E, Sutcliffe C, Verbeek H, Saks K, Soto-Martin M, Meyer G, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions as a best practice strategy in people with dementia living in nursing homes: a systematic review. Eur Geriatr Med. 2015;6:134–50.

Chen R-C, Liu C-L, Lin M-H, Peng L-N, Chen L-Y, Liu L-K, et al. Non-pharmacological treatment reducing not only behavioral symptoms, but also psychotic symptoms of older adults with dementia: a prospective cohort study in Taiwan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14:440–6.

Martin P, Tannenbaum C, Ahmed S, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:890–8.

Lawrence V, Fossey J, Ballard C, Moniz-Cook E, Murray J. Improving quality of life for people with dementia in care homes: making psychosocial interventions work. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:344–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Funding for the conduct of this study was received from the Flemish Agency for Care and Health (Vlaams Agentschap voor Zorg en Gezondheid).

Conflict of interest

Maarten Wauters, Monique Elseviers, Laurine Peeters, Dirk De Meester, Thierry Christiaens and Mirko Petrovic have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. The authors received no support from any organisation for the submitted work, have no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wauters, M., Elseviers, M., Peeters, L. et al. Reducing Psychotropic Drug Use in Nursing Homes in Belgium: An Implementation Study for the Roll-Out of a Practice Improvement Initiative. Drugs Aging 36, 769–780 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00686-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00686-5