Abstract

Background

Cumulative anticholinergic exposure (anticholinergic burden) has been linked to a number of adverse outcomes. To conduct research in this area, an agreed approach to describing anticholinergic burden is needed.

Objective

This review set out to identify anticholinergic burden scales, to describe their rationale, the settings in which they have been used and the outcomes associated with them.

Methods

A search was performed using the Healthcare Databases Advanced Search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, CINAHL and PsycINFO from inception to October 2016 to identify systematic reviews describing anticholinergic burden scales or tools. Abstracts and titles were reviewed to determine eligibility for review with eligible articles read in full. The final selection of reviews was critically appraised using the ROBIS tool and pre-defined data were extracted; the primary data of interest were the anticholinergic burden scales or tools used.

Results

Five reviews were identified for analysis containing a total of 62 original articles. Eighteen anticholinergic burden scales or tools were identified with variation in their derivation, content and how they quantified the anticholinergic activity of medications. The Drug Burden Index was the most commonly used scale or tool in community and database studies, while the Anticholinergic Risk Scale was used more frequently in care homes and hospital settings. The association between anticholinergic burden and clinical outcomes varied by index and study. Falls and hospitalisation were consistently found to be associated with anticholinergic burden. Mortality, delirium, physical function and cognition were not consistently associated.

Conclusions

Anticholinergic burden scales vary in their rationale, use and association with outcomes. This review showed that the concept of anticholinergic burden has been variably defined and inconsistently described using a number of indices with different content and scoring. The association between adverse outcomes and anticholinergic burden varies between scores and has not been conclusively established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There are multiple available methods to quantify anticholinergic burden. |

The available methods vary in their derivation and association with outcomes. |

An agreed method of quantifying anticholinergic burden is needed to aid future potential research in this field. |

1 Introduction

1.1 Rationale

Medications with anticholinergic properties are widely used for a variety of indications. Such products may not be used primarily for their anticholinergic effect and may not be routinely identified as having anticholinergic activity by practicing clinicians [1]. However, the cumulative effect of multiple medications with anticholinergic effects, known as anticholinergic burden, is potentially significant and is an area of specific concern in the literature [2]. Anticholinergic burden scales are designed to quantify the cumulative exposure to anticholinergic activity [3]. A number of scales have been developed and have been used in a number of clinical settings including inpatients, [4] community dwellers [5] and institutional care [6]. They are referred to by a number of terms, but for simplicity throughout the article ‘anticholinergic burden scale’ will be used.

Older people, with a higher rate of multimorbidity and subsequent polypharmacy, are at higher risk of experiencing anticholinergic burden compared with younger people and with age-related changes to pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are at higher risk of anticholinergic side effects for a given anticholinergic burden [7]. This applies all the more in the frailest groups such as care home residents and people with dementia, where the risk of multimorbidity and polypharmacy is high [8].

Previous reviews have identified that all anticholinergic burden scales in use show an association between anticholinergic burden and at least one adverse outcome [2] and researchers have therefore called for interventions to reduce anticholinergic burden [9]. Clearly, a starting point for such interventions is a clear and consistent understanding of how to quantify and measure anticholinergic burden. Preliminary reading of the published reviews, however, showed variation in the type and number of scales/tools identified, with Salahudeen et al. [1] identifying seven and Mayer et al. [10] identifying 12. In addition there was variation in the authors’ views on the appropriateness of the different scales/tools, with Cardwell et al. [2] advocating the use of the Drug Burden Index while Salahudeen et al. [1] identified the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale as the most frequently validated scale. To help clarify this divergence of view, a review of reviews was proposed to comprehensively identify anticholinergic burden scales and tools.

1.2 Objectives

The primary objective of this systematic review of reviews was to identify scales/tools that have been used to quantify anticholinergic burden. The secondary objectives of this review were (1) to describe the rationale of the identified scales; (2) to describe the settings in which the identified scales have been used; and (3) to describe any associations between anticholinergic burden, as quantified by the identified anticholinergic burden scales, and adverse outcomes.

2 Methods

2.1 Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

Systematic reviews describing the use of scales or tools to quantify anticholinergic burden were deemed eligible. For the purposes of this review, articles that stated that they were planned and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [11] were deemed to be systematic. No publication date or age of participant restrictions were imposed but the search was limited to reviews and English language articles. Reviews marked as narrative or clinical were excluded as were reviews that sought to test the association between prespecified anticholinergic burden scales and outcomes.

2.2 Information Sources and Study Selection

An electronic literature search was performed using a Healthcare Databases Advanced Search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, CINAHL and PsycINFO from inception to October 2016 for relevant articles. The last full search was run on 24 October, 2016.

2.3 Search

The following terms, a mixture of MeSH and free text, were used:

Anticholinergics OR cholinergic receptor blocking agents OR cholinergic antagonist OR antimuscarinics OR muscarinic receptor blocking agents OR muscarinic antagonist AND risk OR risk measure OR risk scale OR rating scale OR risk tool OR load OR drug burden index. An example search (MEDLINE) is given in Appendix S1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). The reference lists of included reviews were searched for additional relevant studies (snowballing).

2.4 Study Selection

The titles and abstracts of the identified articles were screened to see whether they met the inclusion criteria. Where there was uncertainty, full-length articles were evaluated before a final decision on inclusion was made. A list of excluded studies is included in Table S1 of the ESM.

2.5 Data Collection

Full-text copies of included articles were reviewed and data were extracted and entered into a structured Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA) database. For each article, the following variables were populated: (1) the anticholinergic burden scales used; (2) information on the scales’ rationale; (3) the number of participants evaluated using the different scales; (4) the use of the scales in different settings [hospital, community, care home (including nursing homes, long-term care facilities and homes for the aged), database studies and in people with dementia]; and (5) (where available) adverse events associated with anticholinergic burden as defined by different anticholinergic burden scales.

2.6 Assessment of Risk of Bias

The ROBIS tool was used to assess the risk of bias for each systematic review [12]. The ROBIS tool is a method to assess bias in systematic reviews that is completed in three phases: (1) assessing relevance; (2) identifying concerns with the review process; and (3) judging risk of bias in the review. Phase two involves assessing the review across four domains: (1) study eligibility criteria, (2) identification and selection of studies, (3) data collection and study appraisal; and (4) synthesis and findings. In phase three, the findings of phase two and signalling questions are used to evaluate the overall risk of bias. Table 1 summarises the risk of bias for each review.

3 Results

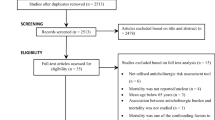

The search identified 4656 articles. After limiting the search to review articles in English, 906 citations remained. The abstracts of these remaining articles were screened and 14 full-text papers were identified and subsequently reviewed for inclusion. From this group, a final total of five were included after a detailed review revealed that nine articles did not meet the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses literature search and study selection flowchart [11]

3.1 Characteristics of Included Reviews

Four of the review articles aimed to identify anticholinergic burden scales and to test their association with clinical outcomes [1, 2, 7, 10]. Two produced an anticholinergic burden scale by combining pre-existing scales, [1, 3] and one aimed to identify the most useful scale for longitudinal research [2].

The five reviews cited a combined total of 62 original research articles. They included variable numbers of primary studies: Cardwell [2] 13 studies, Durán et al. [3] 7 studies, Mayer [10] 55 studies, Salahudeen [1] 38 studies and Villalba-Moreno [7] 25 studies. All reported on an association with adverse outcomes. The characteristics of the cited studies are summarised in Table 2. Sixty of the articles reported on observational studies, while the remaining two reported on randomised controlled trials. Of the 60 observational studies, 30 were cross-sectional and 30 longitudinal (including 4 database studies using primary care data). In total, 699,792 people were studied in the 62 articles, with 22,555 people recruited from the community, 6172 from a hospital (inpatients), 4253 from outpatients and 5316 from care homes or equivalents. Database studies reported data from 661,496 participants across a variety of settings. The findings of each study are summarised in Table 2.

3.2 Synthesis of Reviews

3.2.1 Anticholinergic Burden Scales

Eighteen different anticholinergic burden scales were identified between the five reviews. No single review identified all 18 anticholinergic burden scales. Nine were developed by teams in USA [30, 38, 51, 53, 67, 73, 75, 76], eight were produced by teams based in the UK [74], Israel [13], Norway [14], France [5], Italy [50], Ecuador [3] and New Zealand, [1] while one scale aimed to be international in outlook [70]. The evidence used to develop the scales varied between in vitro receptor binding testing to expert opinion and is summarised in Table 3.

3.2.2 Agreement between Scales

Salahudeen et al. [1] compared the drugs included in the Anticholinergic Drug Scale, Anticholinergic Burden Classification, Clinician-Rated Anticholinergic Score, Anticholinergic Risk Scale, Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale, Anticholinergic Activity Scale and Anticholinergic Loading Scale. Out of 195 medications, 34 (17%) were scored differently in different scales and 12 (6%) were scored as having low anticholinergic effect in at least one scale but having high anticholinergic activity in another.

3.2.3 Population Sizes

The Drug Burden Index was used to quantify the anticholinergic burden in the largest number of participants, followed by the Anticholinergic Risk Scale, Anticholinergic Drug Scale and Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale while the Anticholinergic Activity Scale was applied in the smallest population. Table S2 of the ESM summarises the numbers of participants assessed using the different scales.

3.2.4 Population Settings

The reviews identified studies conducted in a number of different settings; with some conducted in multiple settings. These included the community [8, 14, 16, 18,19,20,21,22, 24, 29, 33, 34, 37, 52, 53, 58, 66, 67, 69, 74, 79] (21), hospital [4, 13, 17, 23, 25, 27, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 45, 46, 56, 57, 68, 70] (19), outpatients [18, 26, 28, 48, 49, 73] (6), care homes (or equivalents) [5, 6, 15, 18, 19, 30,31,32, 38, 39, 42, 43, 47, 55, 59, 63,64,65, 72] (19) and databases [37, 44, 62, 71] (4).

The Drug Burden Index was the most commonly used scale in the community and in database studies, while the Anticholinergic Risk Scale dominated in care homes and hospital settings. Table S3 of the ESM summarises the numbers of participants assessed using the different scales.

3.2.5 Dementia

Eight out of the 62 studies involved populations where all participants had dementia. The Drug Burden Index was the most commonly used scale followed by the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale. Table 4 shows a further breakdown.

3.2.6 Association with Adverse Outcomes

Of the studies reporting outcomes related to falls and hospitalisation, all reported an association with anticholinergic burden. Of the studies reporting mortality, delirium and physical function outcomes, the majority found an association with anticholinergic burden. Of the studies reporting on cognitive function, the majority showed no association with anticholinergic burden. Table 5 shows further details.

4 Discussion

This review of reviews has demonstrated that multiple different scales have been developed to quantify anticholinergic burden. These have been developed variously based on expert opinion, clinical anticholinergic effects and in vitro testing. They have been applied to outpatients, inpatients, community dwellers and care home residents and in database studies. The Drug Burden Index was the most frequently used scale/tool as reported by these studies. More studies reported an association between increasing anticholinergic burden and falls, hospitalisation, mortality and physical function than those that did not. Although more studies reported an association with cognitive function than those that did not, the studies reporting no association involved more participants.

This review identified studies using 18 different anticholinergic burden scales, more than any of the individual reviews, [1,2,3, 7, 10] suggesting that this approach has been more comprehensive. The individual studies identified as part of this review occurred in a number of different settings and included a number of large scale database/population studies. Findings drawn from these data are therefore likely to be applicable in a number of different settings.

The chief limitation of the approach taken in this review is the potential for bias introduced by including only previous reviews, rather than seeking out newer empirical studies published in the interim. Some potentially pertinent studies may have been missed by this method and since the completion of this review we have become aware of one such example [80]. However, this potential has been mitigated to a degree by the number of reviews included and their recent publication dates. In addition, the primary focus of this review was to identify existent scales rather than to assess the association between anticholinergic burden and outcomes. We have chosen to present data on the association with outcomes where it has been reported in the included reviews. However, reviews whose principal aim was to examine this association were not included and this does potentially introduce bias. This is mitigated to a degree by the large number of included studies. Finally, the use of only a single reviewer was not ideal and this may have increased the risk of missing relevant studies. However, the fact that this review identified more anticholinergic burden scales than any of the individual reviews suggests this is unlikely to have been a significant problem.

Anticholinergic burden in older people has been studied extensively; [1, 3] however, the variation in anticholinergic burden scales used, the metrics used to assess outcomes and the outcomes themselves make it challenging to synthesise the data. The reviews all concluded that there is a lack of a universal approach to assessing anticholinergic burden, which handicaps the interpretation of any findings. The different scales include different drugs and attribute markedly different anticholinergic activity to the same drugs [3]. Salahudeen et al. [1] and Durán et al. [3] both propose new scales derived from synthesis of the existing scales but at the time of this review of reviews these had not been tested.

A larger population had been assessed using the Drug Burden Index than any other anticholinergic burden scale because of its use in database studies and it has been shown to be associated with a number of outcomes of interest [71]. However, the approach is more time consuming than other anticholinergic burden scales and copyright restrictions on the use of the ‘Drug Burden Index Calculator’, which limits its use to registered Australian healthcare practitioners, [81] inevitably curbs its potential widespread application. Discounting the Drug Burden Index, the Anticholinergic Risk Scale was the most frequently used scale in care home and inpatient studies, while the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale was the most frequently used in community dwellers and in people with dementia. Both the Anticholinergic Risk Scale and Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale were associated with outcomes of interest, although within the studies examining people with dementia, the association between anticholinergic burden and outcomes was variable and inconsistent. The lack of a clear association between anticholinergic burden and cognitive outcomes was surprising and is an area that warrants closer investigation.

5 Conclusion

There are at least 18 anticholinergic burden scales. These scales vary in their derivation, content and rating of the anticholinergic activity of the same medications. Although the Drug Burden Index has been most extensively used, there are practical considerations that limit its implementation. Of the remaining scales, the Anticholinergic Risk Scale and Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden scale have the most experience in rating anticholinergic burden in care home residents and people with dementia, respectively. The Anticholinergic Risk Scale shows an association with relevant clinical outcomes while the data for the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden scale in people with dementia are mixed.

Although the approach has been hampered by methodological issues, this review has suggested that the evidence of an association between anticholinergic burden and adverse outcomes is not as clear cut as some authors have suggested. Two avenues of enquiry will need to be pursued to help clarify the association between anticholinergic burden and outcomes. First, a formal systematic review of the use of anticholinergic burden scales as reported in original research articles with particular focus placed on the quality of the evidence is needed. Second, additional empirical research testing the use of the most evidence-based scales in their appropriate clinical context is needed to better understand whether the differences in classification and weighting of anticholinergic effects in different scales are justified. By combining these two approaches, greater clarity on the association between anticholinergic burden, as reported by anticholinergic burden scales, and outcomes will be achieved.

References

Salahudeen MS, Duffull SB, Nishtala PS. Anticholinergic burden quantified by anticholinergic risk scales and adverse outcomes in older people: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:31.

Cardwell K, Hughes CM, Ryan C. The association between anticholinergic medication burden and health related outcomes in the ‘oldest old’: a systematic review of the literature. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(10):835–48.

Durán CE, Azermai M, Vander Stichele RH. Systematic review of anticholinergic risk scales in older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(7):1485–96.

Zimmerman KM, Salow M, Skarf LM, et al. Increasing anticholinergic burden and delirium in palliative care inpatients. Palliat Med. 2014;28(4):335–41.

Ancelin ML, Artero S, Portet F, et al. Non-degenerative mild cognitive impairment in elderly people and use of anticholinergic drugs: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2006;332(7539):455–9.

Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The relationship of an anticholinergic rating scale with serum anticholinergic activity in elderly nursing home residents. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36(4):14–9.

Villalba-Moreno AM, Alfaro-Lara ER, Pérez-Guerrero MC, et al. Systematic review on the use of anticholinergic scales in poly pathological patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;62:1–8.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):989–95.

Campbell NL, Perkins AJ, Bradt P, et al. Association of anticholinergic burden with cognitive impairment and health care utilization among a diverse ambulatory older adult population. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(11):1123–31.

Mayer T, Haefeli WE, Seidling HM. Different methods, different results–how do available methods link a patient’s anticholinergic load with adverse outcomes? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(11):1299–314.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, et al. ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–34.

Aizenberg D, Sigler M, Weizman A, et al. Anticholinergic burden and the risk of falls among elderly psychiatric inpatients: a 4-year case-control study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(3):307–10.

Ehrt U, Broich K, Larsen JP, et al. Use of drugs with anticholinergic effect and impact on cognition in Parkinson’s disease: a cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(2):160–5.

Kolanowski A, Fick DM, Campbell J, et al. A preliminary study of anticholinergic burden and relationship to a quality of life indicator, engagement in activities, in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(4):252–7.

Campbell NL, Boustani MA, Lane KA, et al. Use of anticholinergics and the risk of cognitive impairment in an African American population. Neurology. 2010;75(2):152–9.

Campbell NL, Khan BA, Farber M, et al. Improving delirium care in the intensive care unit: the design of a pragmatic study. Trials. 2011;12:139.

Fox C, Livingston G, Maidment ID, et al. The impact of anticholinergic burden in Alzheimer’s dementia-the LASER-AD study. Age Ageing. 2011;40(6):730–5.

Fox C, Richardson K, Maidment ID, et al. Anticholinergic medication use and cognitive impairment in the older population: the medical research council cognitive function and ageing study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1477–83.

Cai X, Campbell N, Khan BC, et al. Long-term anticholinergic use and the aging brain. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(4):377–85.

Koyama A, Steinman M, Ensrud K, et al. Long-term cognitive and functional effects of potentially inappropriate medications in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(4):423–9.

Koyama A, Steinman M, Ensrud K, et al. Ten-year trajectory of potentially inappropriate medications in very old women: importance of cognitive status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):258–63.

Pasina L, Djade CD, Lucca U, et al. Association of anticholinergic burden with cognitive and functional status in a cohort of hospitalized elderly: comparison of the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale and anticholinergic risk scale: results from the REPOSI study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(2):103–12.

Shah RC, Janos AL, Kline JE, et al. Cognitive decline in older persons initiating anticholinergic medications. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64111.

Kidd AC, Musonda P, Soiza RL, et al. The relationship between total anticholinergic burden (ACB) and early in-patient hospital mortality and length of stay in the oldest old aged 90 years and over admitted with an acute illness. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(1):155–61.

Kashyap M, Belleville S, Mulsant BH, et al. Methodological challenges in determining longitudinal associations between anticholinergic drug use and incident cognitive decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(2):336–41.

Mangoni AA, van Munster BC, Woodman RJ, et al. Measures of anticholinergic drug exposure, serum anticholinergic activity, and all-cause postdischarge mortality in older hospitalized patients with hip fractures. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(8):785–93.

Lanctôt KL, O’Regan J, Schwartz Y, et al. Assessing cognitive effects of anticholinergic medications in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(1):61–8.

Sittironnarit G, Ames D, Bush AI, et al. Effects of anticholinergic drugs on cognitive function in older Australians: results from the AIBL study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;31(3):173–8.

Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(12):1481–6.

Kersten H, Molden E, Tolo IK, et al. Cognitive effects of reducing anticholinergic drug burden in a frail elderly population: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):271–8.

Kersten H, Molden E, Willumsen T, et al. Higher anticholinergic drug scale (ADS) scores are associated with peripheral but not cognitive markers of cholinergic blockade: cross sectional data from 21 Norwegian nursing homes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(3):842–9.

Lampela P, Lavikainen P, Garcia-Horsman JA, et al. Anticholinergic drug use, serum anticholinergic activity, and adverse drug events among older people: a population-based study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(5):321–30.

Low LF, Anstey KJ, Sachdev P. Use of medications with anticholinergic properties and cognitive function in a young-old community sample. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(6):578–84.

Juliebø V, Bjøro K, Krogseth M, et al. Risk factors for preoperative and postoperative delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1354–61.

Drag L, Wright S, Bieliauskas L. Prescribing practices of anticholinergic medications and their association with cognition in an extended care setting. J Appl Gerontol. 2012;31(2):239–59.

Kalisch Ellett LM, Pratt NL, Ramsay EN, et al. Multiple anticholinergic medication use and risk of hospital admission for confusion or dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(10):1916–22.

Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, et al. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(5):508–13.

Kumpula EK, Bell JS, Soini H, et al. Anticholinergic drug use and mortality among residents of long-term care facilities: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51(2):256–63.

Lowry E, Woodman RJ, Soiza RL, et al. Associations between the anticholinergic risk scale score and physical function: potential implications for adverse outcomes in older hospitalized patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(8):565–72.

Lowry E, Woodman RJ, Soiza RL, et al. Clinical and demographic factors associated with antimuscarinic medication use in older hospitalized patients. Hosp Pract. 2011;39(1):30–6.

Koshoedo S, Soiza RL, Purkayastha R, et al. Anticholinergic drugs and functional outcomes in older patients undergoing orthopaedic rehabilitation. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(4):251–7.

Landi F, Dell’Aquila G, Collamati A, et al. Anticholinergic drug use and negative outcomes among the frail elderly population living in a nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(11):825–9.

Huang K, Chan F, Shih H, et al. Relationship between potentially inappropriate anticholinergic drugs (PIADs) and adverse outcomes among elderly patients in Taiwan. J Food Drug Anal. 2012;20(4):930–7.

Bostock CV, Soiza RL, Mangoni AA. Associations between different measures of anticholinergic drug exposure and Barthel Index in older hospitalized patients. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013;4(6):235–45.

Dispennette R, Elliott D, Nguyen L, et al. Drug Burden Index score and anticholinergic risk scale as predictors of readmission to the hospital. Consult Pharm. 2014;29(3):158–68.

Teramura-Grönblad M, Muurinen S, Soini H, et al. Use of anticholinergic drugs and cholinesterase inhibitors and their association with psychological well-being among frail older adults in residential care facilities. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(5):596–602.

Walter PJ, Dieter AA, Siddiqui NY, et al. Perioperative anticholinergic medications and risk of catheterization after urogynecologic surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):163–7.

Cancelli I, Valentinis L, Merlino G, et al. Drugs with anticholinergic properties as a risk factor for psychosis in patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(1):63–8.

Cancelli I, Gigli GL, Piani A, et al. Drugs with anticholinergic properties as a risk factor for cognitive impairment in elderly people: a population-based study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(6):654–9.

Chew ML, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, et al. Anticholinergic activity of 107 medications commonly used by older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1333–41.

Jessen F, Kaduszkiewicz H, Daerr M, et al. Anticholinergic drug use and risk for dementia: target for dementia prevention. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260(Suppl. 2):S111–5.

Han L, Agostini JV, Allore HG. Cumulative anticholinergic exposure is associated with poor memory and executive function in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2203–10.

Agar M, Currow D, Plummer J, et al. Changes in anticholinergic load from regular prescribed medications in palliative care as death approaches. Palliat Med. 2009;23(3):257–65.

Yeh YC, Liu CL, Peng LN, et al. Potential benefits of reducing medication-related anticholinergic burden for demented older adults: a prospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13(3):694–700.

Han L, McCusker J, Cole M, et al. Use of medications with anticholinergic effect predicts clinical severity of delirium symptoms in older medical inpatients. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(8):1099–105.

Best O, Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, et al. Investigating polypharmacy and drug burden index in hospitalised older people. Intern Med J. 2013;43(8):912–8.

Gnjidic D, Cumming RG, Le Couteur DG, et al. Drug Burden Index and physical function in older Australian men. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(1):97–105.

Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Abernethy DR, et al. Drug burden index and Beers criteria: impact on functional outcomes in older people living in self-care retirement villages. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(2):258–65.

Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Naganathan V, et al. Effects of drug burden index on cognitive function in older men. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(2):273–7.

Gnjidic D, Bell JS, Hilmer SN, et al. Drug Burden Index associated with function in community-dwelling older people in Finland: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med. 2012;44(5):458–67.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Hartikainen S, et al. Impact of high risk drug use on hospitalization and mortality in older people with and without Alzheimer’s disease: a national population cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e83224.

Wilson NM, Hilmer SN, March LM, et al. Associations between drug burden index and physical function in older people in residential aged care facilities. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):503–7.

Wilson NM, Hilmer SN, March LM, et al. Associations between drug burden index and falls in older people in residential aged care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(5):875–80.

Wilson NM, Hilmer SN, March LM, et al. Associations between drug burden index and mortality in older people in residential aged care facilities. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(2):157–65.

Cao YJ, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. Physical and cognitive performance and burden of anticholinergics, sedatives, and ACE inhibitors in older women. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(3):422–9.

Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):781–7.

Lowry E, Woodman RJ, Soiza RL, et al. Drug burden index, physical function, and adverse outcomes in older hospitalized patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(10):1584–91.

Lönnroos E, Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, et al. Drug Burden Index and hospitalization among community-dwelling older people. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(5):395–404.

Dauphinot V, Faure R, Omrani S, et al. Exposure to anticholinergic and sedative drugs, risk of falls, and mortality: an elderly inpatient, multicenter cohort. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34(5):565–70.

Nishtala PS, Narayan SW, Wang T, et al. Associations of drug burden index with falls, general practitioner visits, and mortality in older people. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(7):753–8.

Bosboom PR, Alfonso H, Almeida OP, et al. Use of potentially harmful medications and health-related quality of life among people with dementia living in residential aged care facilities. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2012;2(1):361–71.

Minzenberg MJ, Poole JH, Benton C, et al. Association of anticholinergic load with impairment of complex attention and memory in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(1):116–24.

Whalley LJ, Sharma S, Fox HC, et al. Anticholinergic drugs in late life: adverse effects on cognition but not on progress to dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30(2):253–61.

Boustani M, Campbell N, Munger S, et al. Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: a review and practical application. Aging Health. 2008;4(3):311–20.

Summers WK. A clinical method of estimating risk of drug induced delirium. Life Sci. 1978;22(17):1511–6.

Mosby. Mosby’s drug consult for health professions. C.V. Mosby Publishing Co, Missouri; 2004.

Physicians’ desk reference. 58th ed. Montvale (NJ): Thomson PDR; 2016.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. High-risk prescribing and incidence of frailty among older community-dwelling men. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(3):521–8.

Klamer TT, Wauters M, Azermai M, et al. A novel scale linking potency and dosage to estimate anticholinergic exposure in older adults: the Muscarinic Acetylcholinergic Receptor Antagonist Exposure Scale. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;120(6):582–90.

Kouladjian L, Gnjidic D, Chen T, et al. DBI Calculator©. The Drug Burden Index Calculator 2016 [cited 2016 08 Nov 2016]; 1:[The Drug Burden Index Calculator]. Available from: https://drugburdenindex.com/Account/Login?ReturnUrl=%2f.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Conflict of Interest

Tomas Welsh, Veronika Van der Wardt, Grace Ojo, Adam Gordon and John Gladman have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this review.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Welsh, T.J., van der Wardt, V., Ojo, G. et al. Anticholinergic Drug Burden Tools/Scales and Adverse Outcomes in Different Clinical Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Drugs Aging 35, 523–538 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-018-0549-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-018-0549-z