Abstract

Approximately 40 % of patients with bipolar disorder experience mixed episodes, defined as a manic state with depressive features, or manic symptoms in a patient with bipolar depression. Compared with bipolar patients without mixed features, patients with bipolar mixed states generally have more severe symptomatology, more lifetime episodes of illness, worse clinical outcomes and higher rates of comorbidities, and thus present a significant clinical challenge. Most clinical trials have investigated second-generation neuroleptic monotherapy, monotherapy with anticonvulsants or lithium, combination therapy, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Neuroleptic drugs are often used alone or in combination with anticonvulsants or lithium for preventive treatment, and ECT is an effective treatment for mixed manic episodes in situations where medication fails or cannot be used. Common antidepressants have been shown to worsen mania symptoms during mixed episodes without necessarily improving depressive symptoms; thus, they are not recommended during mixed episodes. A greater understanding of pathophysiological processes in bipolar disorder is now required to provide a more accurate diagnosis and new personalised treatment approaches. Targeted, specific treatments developed through a greater understanding of bipolar disorder pathophysiology, capable of affecting the underlying disease processes, could well prove to be more effective, faster acting, and better tolerated than existing therapies, therefore providing better outcomes for individuals affected by bipolar disorder. Until such time as targeted agents are available, second-generation neuroleptics are emerging as the treatment of choice in the management of mixed states in bipolar disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mixed states in bipolar disorder are difficult to diagnose and treat, with patients having a more severe symptomatology than those without mixed features. |

Neuroleptic therapy with or without mood stabilisers is the cornerstone of treatment for mixed states in bipolar disorder, with second-generation neuroleptics emerging as particularly effective in these patients. |

A greater understanding of the underlying mechanisms of mixed states in bipolar disorder will lead to more effective therapies and improved outcomes. |

1 Introduction

In bipolar disorder, the simultaneous occurrence of both manic and depressive symptoms in an individual is termed ‘mixed states’ [1]. Typically, these take the form of a manic state with depressive features, or manic symptoms in a patient with depression [2].

Mixed states can be highly heterogeneous. Evidence suggests that mixed states in bipolar disorder were recognised as early as the 1800s, but achieving a consensus on the appropriate definitions and classifications for these states has been challenging [1]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria (now superseded by DSM, Fifth Edition [DSM-5]) were quite stringent, in that patients had to meet criteria for both manic and depressive episodes nearly every day for ≥1 week [3]. Various other definitions have also been used over the past number of years, including definitions requiring a certain number of depressive symptoms [4], although these have generally not gained traction. The pivotal BRIDGE (Bipolar Disorders: Improving Diagnosis, Guidance and Education) study suggested that bipolar disorder exists on a continuum [5], and the new DSM-5 criteria for mixed states are less constraining than DSM-IV-TR, and also acknowledge the presentation of mixed states in the context of bipolar II disorder and major depressive disorder [6]. Like the BRIDGE study, DSM-5 introduced specifiers that can be applied to the manic or depressive poles (three or more items required for each pole); in the manic pole, mixed specifiers include dysphoria or depressed mood, psychomotor retardation, loss of interest and pleasure, fatigue or anergia, worthlessness, and thoughts of death, while in the depression pole, mixed specifiers include elevated mood, decreased need for sleep, grandiosity, increased goal-directed activities, increased engagement in potentially risky endeavours, pressure of speech, and flight of ideas. In addition, DSM-5 includes an acknowledgement that manic symptoms can coexist within a major depressive episode, via the inclusion of the ‘with mixed features’ specifier for major depressive disorder [6].

Although the DSM-5 criteria improved on those of DSM-IV-TR, the results of the BRIDGE-II study suggest that use of alternative criteria such as the Research-Based Diagnostic Criteria can identify as many as 29.1 % of patients with depressive mixed states versus 15.4 % when DSM-5 criteria are used [7]. However, there are data indicating an increase in the prevalence of mixed states in bipolar disorder following replacement of DSM-IV-TR criteria with DSM-5 criteria [8]; a retrospective chart review of Korean patients diagnosed with bipolar I, bipolar II or bipolar not otherwise specified according to DSM-IV-TR criteria showed that reclassification of patients according to DSM-V criteria increased the prevalence of bipolar with mixed features from 6.0 to 19.6 % (p < 0.001) [8]. Overall, the literature suggests that a significant proportion (~40 %) of patients with bipolar I disorder experience mixed episodes [9–12].

This review aims to present an overview of the issues associated with the diagnosis and treatment of patients with mixed-states bipolar disorder, summarise the clinical trial data on the treatment of mixed states with pharmacological agents and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and provide some practical guidance for physicians managing these patients in their clinic.

1.1 Literature Search

As this was a narrative review, the search was not conducted systematically. Papers were obtained using a PubMed search (not limited by date) and a variety of keywords, including ‘bipolar disorder’ and ‘mixed states’, as well as section-specific keywords of relevance (e.g. substance abuse). The reference lists of recent papers obtained in the search were analysed, and relevant papers from those bibliographies included. Additional papers were also included at the authors’ discretion, based on their clinical experience.

2 Challenges in Diagnosing Mixed Bipolar States

Even when using the DSM-5 mixed-episode specifiers, the diagnosis of mixed bipolar states can be difficult, with the large number of symptom combinations potentially signifying a mixed state complicating diagnosis even when the DSM-5 specifiers are used [13]. Compared with non-mixed episodes, mixed manic episodes are characterised by greater mood lability and irritability, and lesser grandiosity, euphoria, need for sleep and pressured speech [14, 15]. The manic symptoms associated with mixed episodes appear to vary in severity, having been reported as less severe, more severe and similar to non-mixed manic episodes [14]. Depressive symptoms associated with mixed manic episodes include dysphoric mood, anxiety, excessive guilt and suicidality [15]. Depression and anxiety in mixed manic episodes are similar in severity to agitated depressive episodes without other manic symptoms (defined as a major depressive episode with at least two of the following: pacing; hand-wringing; inability to sit still; pulling/rubbing skin, clothes, hair or other objects; outbursts of complaining/shouting; talkativeness), but severe agitation, irritability and cognitive impairment are increased [16].

Depressive and manic states are also associated with non-mood symptoms such as anxiety, agitation or psychosis; generally, these are likely to be basic features of mixed states [14]. Some studies have suggested that distractibility and psychomotor agitation are hallmarks of mixed states in bipolar disorder [17], while others suggest that anxiety may be a core symptom of manic mixed states [18]; results from the Investigating Manic Phases And Current Trends (IMPACT) survey suggest that patients with depressive symptoms during mania can be distinguished from those with pure mania by the presence of anxiety together with irritability/agitation [19]. Anxiety in mixed manic episodes is similar to non-manic agitated depression in terms of severity, and is associated with increased intensity of affect and tension [16, 20]. Anxiety is a prominent feature in depressive states, both mixed and non-mixed [14, 16]. Both agitation and psychosis are present in mixed and non-mixed states [14]. With regard to depressive states, features of agitated depression as defined above are similar to those of depressive mixed states (depression with manic symptoms such as irritability, psychomotor agitation, talkativeness, racing/crowded thoughts, psychic agitation), and both states have high levels of suicide ideation [21–25].

A key problem with the literature on mixed bipolar states is the lack of uniform ways of measuring symptoms, and attempts have been made to develop scales. Cavanagh et al. developed an 18-item scale specifically to measure mixed states, which may have clinical utility because it is brief [26]. Items included in the scale are physical and verbal activity, thought processes, voice level, mood, self-esteem, contact, sleep, sexual interest, eating habits, weight change, meaning, anxiety, feelings of pressure, passage of time, future plans, pain sensitivity and work. Henry et al. developed a scale that may be useful in distinguishing bipolar depressed patients with manic symptoms from those without such symptoms [27]. This scale classifies episodes using a continuum from inhibition to activation, and includes emotional reactivity, which is thought to be key to differentiating major depressive episodes with and without manic episodes.

3 Challenges in Treating Patients with Bipolar Mixed States

Compared with bipolar patients without mixed features, patients with bipolar mixed states generally have more severe symptomatology, more lifetime episodes of illness, worse clinical outcomes and higher rates of comorbidities [8, 14, 28–30]. In particular, significant comorbidity is very common in patients with bipolar disorder, with substance abuse being particularly present in the population with mixed states (reviewed by Fagiolini et al. [31] and Castle [1]). Patients with bipolar disorder frequently have high rates of alcohol and cannabis use, and data suggest that bipolar disorder occurs at a higher rate (five- to eightfold) in individuals with substance abuse disorders [31]; comorbid mood disorders occur twice as frequently in patients with substance abuse disorders than the general population. While the reasons why patients with bipolar mixed states are prone to substance abuse have not been fully elucidated [1], some data suggest that a history of substance abuse disorder can lead to greater mood instability in patients with bipolar disorder experiencing depressive episodes, which may result in an increased risk of mixed episodes [14]. Borderline personality disorder is also commonly seen in patients with mixed-states bipolar disorder, with significant overlap of the symptoms between the depressive and hypomanic mixed states of bipolar II and borderline personality disorder [31]. Patients with bipolar disorders often have residual symptoms, and borderline personality disorder can have an unstable and partly remitting disease course, and as many as one in five patients with borderline personality disorder meet the criteria for bipolar disorder; these factors can mean substantial difficulty in obtaining a correct diagnosis [31]. Some studies have suggested that although the fronto-limbic network is dysfunctional in both bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder, the regulation of emotional processes are different, and this may provide a mechanism for distinguishing the two [32].

Patients with bipolar mixed states report that these episodes have a significant impact on their quality of life [13]. Patients who experience mixed episodes generally have an earlier age at onset than those without mixed features [8, 28–30], as well as a delayed diagnosis [19]. Time to symptom resolution is also longer for mixed episodes than for depressive or manic episodes [8, 28–30], and patients with mixed episodes (mania plus more than three depressive features) tend to have shorter symptom-free periods than those without mixed episodes [19]. Mixed states are difficult to treat with drug therapy; response to lithium and other monotherapies is generally poor [14]. Antidepressants are generally avoided in mixed depressive episodes because of exacerbation of manic symptoms and an increased risk for suicidality [1].

4 Clinical Trials Evaluating Treatment of Mixed Bipolar States

More than 30 randomized controlled studies, post hoc analyses and meta-analyses have investigated the pharmacotherapeutic and related treatment of mixed states in bipolar disorder. Most studies have focused on the acute phase of mixed episodes and evaluated the effects of treatment on both the manic and depressive components, while some trials have evaluated maintenance treatment, including the effects on reducing manic, depressive and mixed relapse [33–38].

Treatments that have been investigated in mixed bipolar states include second-generation neuroleptic monotherapy [36, 37, 39–56], anticonvulsant or lithium therapy [33, 57–64], combination therapy [35, 38, 65–72], and ECT [73–76]. Details of these studies will be discussed below. It should be noted that most studies included patients with mixed-states bipolar as part of a broader bipolar population, and did not report separate results for the mixed-states population.

4.1 Second-Generation Neuroleptic Monotherapy

The second-generation neuroleptics investigated in studies of mixed-states bipolar disorder were aripiprazole, asenapine, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone [36, 37, 39–52, 54–56].

The primary endpoint and safety results are summarised in Table 1; generally, active therapy was more effective than placebo in treating mixed episodes in these studies. Use of second-generation neuroleptics seems to be more effective for the treatment of manic symptoms than depressive symptoms [77], although in the studies included in Table 1, there were only two that had change from baseline in depression scores as a primary endpoint (Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS]) [39, 40]. Most studies of acute therapy were placebo-controlled and included patients experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I (Table 1); the use of aripiprazole, asenapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone resulted in significantly greater changes from baseline in Young Mania Rating Scale (Y-MRS) scores and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores versus placebo. In one study, doses of paliperidone extended-release 12 mg/day also led to significant improvements in the Y-MRS versus placebo (Table 1) [50].

Atypical agents used for maintenance therapy in patients with mixed episodes include asenapine, olanzapine, paliperidone and quetiapine (Table 1). Olanzapine was significantly better than placebo at increasing the time to symptomatic relapse when used as maintenance therapy [36, 37], while paliperidone extended-release and quetiapine resulted in similar improvements in the Y-MRS [56]; asenapine and olanzapine also improved the Y-MRS to a similar degree [34].

The reporting of safety endpoints varied between the studies summarised in Table 1. Generally, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred at a similar or greater rate in patients treated with second-generation neuroleptics than placebo in the acute and maintenance setting. Extrapyramidal symptoms were reported more frequently with active therapy than placebo (Table 1).

4.2 Carbamazepine, Lithium and Valproate Monotherpy

Studies have investigated the efficacy of carbamazepine, lithium and valproate in the treatment of mixed episodes [33, 57–64]. Results for the primary efficacy endpoints and tolerability for these studies are summarised in Table 2.

Acute therapy with carbamazepine extended-release led to significant improvements from baseline in the Y-MRS versus placebo in three studies (Table 2) [59–61]. Response to lithium, but not divalproex, decreased with increasing number of mixed episodes in one acute therapy study [58]. Lithium was slightly more effective than valproate in another study, but both drugs were effective in improving symptoms [63]. Use of divalproex improved both mania and depression scale scores when used for acute treatment (Table 2). Tolerability results showed that generally active treatment led to a higher number of adverse events than placebo in the acute setting (Table 2).

A study by Bowden and colleagues investigated the use of divalproex or lithium versus placebo for maintenance therapy in patients who had recovered from a manic episode in the previous 3 months (Table 2) [33]. In this study, efficacy as maintenance therapy was similar between divalproex and lithium. Patients with bipolar mixed states discontinued therapy more often than patients with pure mania [33].

4.3 Combination Therapy

Combination therapies investigated in mixed-states bipolar disorder were haloperidol plus lithium or valproate [68], olanzapine plus lithium or valproate [65, 66, 69, 70], quetiapine plus lithium or valproate [35, 38], risperidone plus lithium or valproate [68], and olanzapine plus fluoxetine [71, 72].

When used for acute therapy, combination therapy was consistently more effective than the component monotherapies or placebo at improving mania and depression symptoms in patients experiencing acute manic, mixed or depressive episodes (Table 3). In terms of tolerability, patients receiving olanzapine as part of their acute combination therapy generally had significantly more weight gain than those receiving monotherapy [69, 70, 72], but in other studies the rate of adverse events was similar between groups [68].

Two studies investigated the use of quetiapine plus lithium or divalproex versus placebo plus lithium or divalproex for maintenance therapy in patients with bipolar I disorder (including mixed states) [35, 38]. In both studies, the use of combination therapy prolonged the time to recurrence of any mood event versus monotherapy, without increasing the rate of adverse events (Table 3).

4.4 Electroconvulsive Therapy

Several studies have investigated the treatment of mixed episodes with ECT, and the results suggest that ECT is effective in this population [73–76]. In addition, patients with bipolar mixed states resistant to medication can often respond to ECT. In a study of 41 patients with bipolar disorder treated with lithium, eight patients did not respond to treatment and were considered for ECT; all of these eight patients met the criteria for a diagnosis of mixed states [75]. Those treated with ECT (n = 7) demonstrated meaningful reductions in symptom severity, for both manic and depressive symptoms [75]. In another group of patients with mixed states considered non-responders to pharmacotherapy (n = 50), ECT resulted in a global response rate (CGI ≤ 2) of 76.0 % and a global remission rate (CGI ≤ 1) of 34.8 %, which was comparable to patients with bipolar depression treated with ECT in the same study (67.4 % and 41.3 %) [73]. When depressive symptoms were measured, similar response (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HAM-D] ≤50 %) and remission rates (HAM-D ≤ 8) were seen between mixed states and bipolar depression (66.0 vs. 69.6 %, and 30.0 vs. 26.1 %, respectively) [73].

Although the number of ECT sessions required for a response was similar between mixed states and bipolar depression in one study (7.4 vs. 7.4) [73], some studies have shown that patients with mixed states require a greater number of treatments than patients with bipolar depression (9.3 vs. 7.1; p < 0.06) and a longer duration of hospitalisation (30.0 vs. 9.0 days; p < 0.03) [76].

5 Translating Study Results to Clinical Practice

The clinical trials presented above suggest that second-generation neuroleptics are being heavily investigated for the treatment of mixed bipolar states, and the results from these studies suggest they are effective for both acute and long-term therapy.

Guidelines including recommendations for the management of patients with mixed episodes are available, and include such recommendations as regularly questioning the patient about suicide ideation, intent to act on suicide plans, and preparation for suicide [78], as well as emphasising the need for long-term medication [78]. For acute treatment, valproate or neuroleptics are recommended; second-generation neuroleptics are a good option because of their favourable side effect profile [78, 79]. For long-term maintenance therapy, lithium, carbamazepine, or valproate are recommended [78]. Generally, patients with mixed episodes will be better controlled on valproate than lithium [79]. British guidelines recommend that the tolerability profile of the various treatment options as well as patient preference should guide prescribing in order to maximise adherence [78], while Canadian guidelines suggest that combination therapy may be the most appropriate treatment course for patients with mixed episodes, therefore the depressive and manic symptoms are both effectively addressed [79].

5.1 Expert Opinion and Practical Guidance

Current treatments for bipolar disorder are largely directed towards ameliorating symptoms of pure polarities (i.e. pure mania or pure depression) and preventing relapse. However, mixed states are prevalent and often more difficult to control than episodes of pure mania or depression. Indeed, mixed states are associated with high risk and adverse prognostic outcomes, particularly suicide. In one recent interview-based study, patients with bipolar mixed states reported that their disease had a substantial impact on many areas of their life, including identity, work, family life, and social and love life [13]. Clinical practice and recent evidence suggest that pure episodes (i.e. episodes with no symptoms of the opposite polarity) of mania or depression are less frequent than episodes with one or more concomitant opposite polarity symptoms [17, 80].

The definition of mixed states has changed; new research will use the DSM-5 definition. However, there is an absence of primary data, and adequately powered trials in mixed states are urgently required. DSM-5 lowered the threshold for the mixed features specifier, which now requires the presence of at least three depressive DSM-5 criterion symptoms during a manic episode or at least three manic DSM-5 criterion symptoms during a depressive episode [6]. Although the new classification provides a better way to describe patients with mixed features, it does not allow a diagnosis of mixed state in those patients with one or two concomitant symptoms of opposite polarity, where, in our opinion, any patient with concomitant symptoms of opposite polarity should be diagnosed and treated as mixed.

The mainstay of treatment of mixed episodes remains anticonvulsants, lithium and neuroleptics. Although lithium has been used for more than 60 years to treat bipolar disorder, and remains a gold standard treatment for mania, it is thought to be less effective when mania and depression occur simultaneously. In our experience, valproate has a more rapid onset of action and, in some studies, has been shown to be more effective than lithium for the treatment of mixed episodes. Several second-generation neuroleptic drugs are effective and are approved by the US FDA for mixed episodes. These include aripiprazole, asenapine, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone. However, there is a lack of primary data regarding efficacy for the newly established DSM-5 categories of mania with depressive symptoms or depression with manic symptoms.

Secondary analyses offer some guidance in treatment choice. For instance, secondary data point to efficacy of asenapine in patients with mania and depressive symptoms. In fact, post hoc analyses show that asenapine reduced depressive symptoms in bipolar I disorder patients experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes with clinically relevant depressive symptoms at baseline; olanzapine results appeared to be less consistent. Of course, the generalizability of these findings need to be confirmed with controlled studies of asenapine in patients with acute bipolar depression [40].

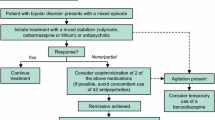

Neuroleptic drugs are often used alone or in combination with anticonvulsants or lithium for preventive treatment. ECT is an effective treatment for mixed manic episodes and can be helpful if medication fails or cannot be used. Common antidepressants have been shown to worsen mania symptoms during mixed episodes without necessarily improving depressive symptoms. We agree with the experts who advise against using antidepressants during mixed episodes. However, it is our practice to consider the use of an antidepressant (always prescribed in concomitance with an antimanic agent, i.e. a neuroleptic or an anticonvulsant or lithium) in those cases when every symptom of ‘activation’ (i.e. anxiety, irritability, agitation, insomnia, active suicidality, etc.) has completely subsided and symptoms of depressed mood, psychomotor retardation, low energy and hypersomnia are present. Despite the fact that bipolar disorder is classified as a mood disorder, we believe that looking at the symptom of depression as the primary informant for treatment choice is often misleading. Instead, it is our practice to look at energy and activation as the first and primary informants; a suggested treatment algorithm is outlined in Fig. 1. When energy and agitation/activation are increased, we prescribe a neuroleptic and/or a classic mood stabilizer (most often valproate) until those symptoms are treated, and we never consider, nor do we advise physicians to consider, the use of an antidepressant. Once energy and activation/agitation are controlled, we usually continue the acute treatment for the longer term. In cases when energy and activation/agitation are profoundly decreased (i.e. the patient experiences psychomotor retardation), if manic symptoms are present and an antimanic treatment is well established at a level that cannot be decreased, the use of an antidepressant may then be considered.

6 Conclusions

Mixed states are relatively common in patients with bipolar disorder. Patients with mixed bipolar states present a clinical challenge since these patients are more frequently resistant to pharmacotherapy, and there may be a possible difference in treatment response for the manic and depressive components of mixed episodes. In general, antidepressants should be avoided in bipolar mixed states, although evidence-based data supporting this are limited. Targeted, specific treatments developed through a greater understanding of bipolar disorder pathophysiology, capable of affecting the underlying disease processes, could well prove to be more effective, faster acting, and better tolerated than existing therapies, therefore providing better outcomes for individuals affected by bipolar disorder. Until such time as targeted agents are available, second-generation neuroleptics are emerging as the treatment of choice in the management of mixed states in bipolar disorder.

References

Castle DJ. Bipolar mixed states: still mixed up? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(1):38–42.

Berk M, Dodd S, Malhi GS. ‘Bipolar missed states’: the diagnosis and clinical salience of bipolar mixed states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(4):215–21.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Benazzi F, Akiskal HS. Delineating bipolar II mixed states in the Ravenna-San Diego collaborative study: the relative prevalence and diagnostic significance of hypomanic features during major depressive episodes. J Affect Disord. 2001;67(1–3):115–22.

Angst J, Azorin JM, Bowden CL, Perugi G, Vieta E, Gamma A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of undiagnosed bipolar disorders in patients with a major depressive episode: the BRIDGE study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):791–8.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Perugi G, Angst J, Azorin JM, Bowden CL, Mosolov S, Reis J, et al. Mixed features in patients with a major depressive episode: the BRIDGE-II-MIX study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):e351–8.

Shim IH, Woo YS, Bahk WM. Prevalence rates and clinical implications of bipolar disorder “with mixed features” as defined by DSM-5. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:120–5.

Dunner DL. Atypical antipsychotics: efficacy across bipolar disorder subpopulations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 3):20–7.

Himmelhoch JM, Mulla D, Neil JF, Detre TP, Kupfer DJ. Incidence and significance of mixed affective states in a bipolar population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33(9):1062–6.

Kessing LV. The prevalence of mixed episodes during the course of illness in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(3):216–24.

Secunda SK, Swann A, Katz MM, Koslow SH, Croughan J, Chang S. Diagnosis and treatment of mixed mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(1):96–8.

Malhi GS. Diagnosis of bipolar disorder: who is in a mixed state? Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1599–600.

Swann AC, Lafer B, Perugi G, Frye MA, Bauer M, Bahk WM, et al. Bipolar mixed states: an international society for bipolar disorders task force report of symptom structure, course of illness, and diagnosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(1):31–42.

Cassidy F, Murry E, Forest K, Carroll BJ. Signs and symptoms of mania in pure and mixed episodes. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2–3):187–201.

Swann AC, Secunda SK, Katz MM, Croughan J, Bowden CL, Koslow SH, et al. Specificity of mixed affective states: clinical comparison of dysphoric mania and agitated depression. J Affect Disord. 1993;28(2):81–9.

Malhi GS, Lampe L, Coulston CM, Tanious M, Bargh DM, Curran G, et al. Mixed state discrimination: a DSM problem that wont go away? J Affect Disord. 2014;158:8–10.

González-Pinto A, Aldama A, Mosquera F, Gómez CG. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of mixed mania. CNS Drugs. 2007;21(8):611–26.

Vieta E, Grunze H, Azorin JM, Fagiolini A. Phenomenology of manic episodes according to the presence or absence of depressive features as defined in DSM-5: results from the IMPACT self-reported online survey. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:206–13.

Henry C, M’Bailara K, Poinsot R, Casteret AA, Sorbara F, Leboyer M, et al. Evidence for two types of bipolar depression using a dimensional approach. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76(6):325–31.

Akiskal HS, Benazzi F, Perugi G, Rihmer Z. Agitated, “unipolar” depression re-conceptualized as a depressive mixed state: implications for the antidepressant-suicide controversy. J Affect Disord. 2005;85(3):245–58.

Benazzi F, Akiskal HS. Psychometric delineation of the most discriminant symptoms of depressive mixed states. Psychiatry Res. 2006;141(1):81–8.

Faedda GL, Marangoni C, Reginaldi D. Depressive mixed states: a reappraisal of Koukopoulos’ criteria. J Affect Disord. 2015;176:18–23.

Sani G, Napoletano F, Vohringer PA, Sullivan M, Simonetti A, Koukopoulos A, et al. Mixed depression: clinical features and predictors of its onset associated with antidepressant use. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(4):213–21.

Koukopoulos A, Sani G. DSM-5 criteria for depression with mixed features: a farewell to mixed depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129(1):4–16.

Cavanagh J, Schwannauer M, Power M, Goodwin GM. A novel scale for measuring mixed states in bipolar disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2009;16(6):497–509.

Henry C, M’Bailara K, Lepine JP, Lajnef M, Leboyer M. Defining bipolar mood states with quantitative measurement of inhibition/activation and emotional reactivity. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1–3):300–4.

Baldessarini RJ, Bolzani L, Cruz N, Jones PB, Lai M, Lepri B, et al. Onset-age of bipolar disorders at six international sites. J Affect Disord. 2010;121(1–2):143–6.

Shim IH, Woo YS, Jun TY, Bahk WM. Mixed-state bipolar I and II depression: time to remission and clinical characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:340–6.

Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ, Valenti M, Pacchiarotti I, Vieta E. Suicidal risk factors in bipolar I and II disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(6):778–82.

Fagiolini A, Forgione R, Maccari M, Cuomo A, Morana B, Dell’Osso MC, et al. Prevalence, chronicity, burden and borders of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(2–3):161–9.

Malhi GS, Tanious M, Fritz K, Coulston CM, Bargh DM, Phan KL, et al. Differential engagement of the fronto-limbic network during emotion processing distinguishes bipolar and borderline personality disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(12):1247–8.

Bowden CL, Collins MA, McElroy SL, Calabrese JR, Swann AC, Weisler RH, et al. Relationship of mania symptomatology to maintenance treatment response with divalproex, lithium, or placebo. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(10):1932–9.

McIntyre RS, Cohen M, Zhao J, Alphs L, Macek TA, Panagides J. Asenapine for long-term treatment of bipolar disorder: a double-blind 40-week extension study. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):358–65.

Suppes T, Vieta E, Liu S, Brecher M, Paulsson B. Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder: results from a North American study of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex (trial 127). Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):476–88.

Tohen M, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, Banov MD, Detke HC, Risser R, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine as maintenance therapy in patients with bipolar I disorder responding to acute treatment with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):247–56.

Tohen M, Sutton VK, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, Bowden CL. Maintenance of response following stabilization of mixed index episodes with olanzapine monotherapy in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of bipolar 1 disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(1–2):43–50.

Vieta E, Suppes T, Eggens I, Persson I, Paulsson B, Brecher M. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in combination with lithium or divalproex for maintenance of patients with bipolar I disorder (international trial 126). J Affect Disord. 2008;109(3):251–63.

Patkar A, Gilmer W, Pae CU, Vohringer PA, Ziffra M, Pirok E, et al. A 6 week randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of ziprasidone for the acute depressive mixed state. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34757.

Szegedi A, Zhao J, van Willigenburg A, Nations KR, Mackle M, Panagides J. Effects of asenapine on depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes: a post hoc analysis of two 3-week clinical trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:101.

Baker RW, Tohen M, Fawcett J, Risser RC, Schuh LM, Brown E, et al. Acute dysphoric mania: treatment response to olanzapine versus placebo. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(2):132–7.

Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J, Wilson M, Calabrese J, Chengappa R, Keck PE Jr, et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in acute mania: treatment responses in subgroups. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(4):370–6.

Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, McElroy SL, Banov MC, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The Olanzapine HGGW Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(9):841–9.

Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KN, Daniel DG, et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Olanzapine HGEH Study Group. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5):702–9.

Shi L, Schuh LM, Trzepacz PT, Huang LX, Namjoshi MA, Tohen M. Improvement of Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale cognitive score associated with olanzapine treatment of acute mania. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(9):1371–6.

Keck PE Jr, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, Ali M, Liebeskind A, Saha A, et al. A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(9):1651–8.

McIntyre RS, Cohen M, Zhao J, Alphs L, Macek TA, Panagides J. A 3-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of asenapine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar mania and mixed states. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(7):673–86.

Sachs G, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R, Carson W, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder: a 3-week placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(4):536–46.

Suppes T, Eudicone J, McQuade R, Pikalov A 3rd, Carlson B. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in subpopulations with acute manic or mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;107(1–3):145–54.

Berwaerts J, Xu H, Nuamah I, Lim P, Hough D. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of paliperidone extended-release in the treatment of acute mania: a randomized, double-blind, dose-response study. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(1–2):e51–60.

Keck PE Jr, Versiani M, Potkin S, West SA, Giller E, Ice K. Ziprasidone in the treatment of acute bipolar mania: a three-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):741–8.

Khanna S, Vieta E, Lyons B, Grossman F, Eerdekens M, Kramer M. Risperidone in the treatment of acute mania: double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:229–34.

McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Faedda GL, Swann AC. Clinical and research implications of the diagnosis of dysphoric or mixed mania or hypomania. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(12):1633–44.

Potkin SG, Keck PE Jr, Segal S, Ice K, English P. Ziprasidone in acute bipolar mania: a 21-day randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled replication trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(4):301–10.

Stahl S, Lombardo I, Loebel A, Mandel FS. Efficacy of ziprasidone in dysphoric mania: pooled analysis of two double-blind studies. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):39–45.

Vieta E, Nuamah IF, Lim P, Yuen EC, Palumbo JM, Hough DW, et al. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled study of paliperidone extended release for the treatment of acute manic and mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(3):230–43.

Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, et al. Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. The Depakote Mania Study Group. JAMA. 1994;271(12):918–24.

Swann AC, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Dilsaver SC, Morris DD. Mania: differential effects of previous depressive and manic episodes on response to treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(6):444–51.

Weisler RH, Hirschfeld R, Cutler AJ, Gazda T, Ketter TA, Keck PE, et al. Extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy in bipolar disorder : pooled results from two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(3):219–31.

Weisler RH, Kalali AH, Ketter TA. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for bipolar disorder patients with manic or mixed episodes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):478–84.

Weisler RH, Keck PE Jr, Swann AC, Cutler AJ, Ketter TA, Kalali AH. Extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for acute mania in bipolar disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(3):323–30.

Bowden CL, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Rubenfaer LM, Wozniak PJ, Collins MA, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of divalproex sodium extended release in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(10):1501–10.

Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, Lesem MD, Swann AC. A double-blind comparison of valproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(1):108–11.

Ghaemi SN, Gilmer WS, Goldberg JF, Zablotsky B, Kemp DE, Kelley ME, et al. Divalproex in the treatment of acute bipolar depression: a preliminary double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(12):1840–4.

Baker RW, Brown E, Akiskal HS, Calabrese JR, Ketter TA, Schuh LM, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine combined with valproate or lithium in the treatment of dysphoric mania. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:472–8.

Houston JP, Ahl J, Meyers AL, Kaiser CJ, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ. Reduced suicidal ideation in bipolar I disorder mixed-episode patients in a placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine combined with lithium or divalproex. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(8):1246–52.

Houston JP, Ketter TA, Case M, Bowden C, Degenhardt EK, Jamal HH, et al. Early symptom change and prediction of subsequent remission with olanzapine augmentation in divalproex-resistant bipolar mixed episodes. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(2):169–73.

Sachs GS, Grossman F, Ghaemi SN, Okamoto A, Bowden CL. Combination of a mood stabilizer with risperidone or haloperidol for treatment of acute mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of efficacy and safety. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(7):1146–54.

Tohen M, Chengappa KN, Suppes T, Zarate CA Jr, Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine in combination with valproate or lithium in the treatment of mania in patients partially nonresponsive to valproate or lithium monotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(1):62–9.

Houston JP, Tohen M, Degenhardt EK, Jamal HH, Liu LL, Ketter TA. Olanzapine-divalproex combination versus divalproex monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar mixed episodes: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(11):1540–7.

Benazzi F, Berk M, Frye MA, Wang W, Barraco A, Tohen M. Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for the treatment of mixed depression in bipolar I disorder: a post hoc analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1424–31.

Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, Ketter TA, Sachs G, Bowden C, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1079–88.

Medda P, Perugi G, Zanello S, Ciuffa M, Rizzato S, Cassano GB. Comparative response to electroconvulsive therapy in medication-resistant bipolar I patients with depression and mixed state. J ECT. 2010;26(2):82–6.

Valenti M, Benabarre A, Garcia-Amador M, Molina O, Bernardo M, Vieta E. Electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of mixed states in bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(1):53–6.

Gruber NP, Dilsaver SC, Shoaib AM, Swann AC. ECT in mixed affective states: a case series. J ECT. 2000;16(2):183–8.

Devanand DP, Polanco P, Cruz R, Shah S, Paykina N, Singh K, et al. The efficacy of ECT in mixed affective states. J ECT. 2000;16(1):32–7.

Fountoulakis KN, Kontis D, Gonda X, Siamouli M, Yatham LN. Treatment of mixed bipolar states. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(7):1015–26.

Goodwin GM. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(4):346–88.

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, Parikh S, MacQueen G, McIntyre R, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: consensus and controversies. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(Suppl 3):5–69.

Goldberg JF, Perlis RH, Bowden CL, Thase ME, Miklowitz DJ, Marangell LB, et al. Manic symptoms during depressive episodes in 1380 patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):173–81.

McIntyre RS, Cohen M, Zhao J, Alphs L, Macek TA, Panagides J. Asenapine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):27–38.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sheridan Henness, PhD, of Springer Healthcare Communications, for medical writing assistance, including drafting of the manuscript, English editing of the ‘Expert Opinion and Practical Guidance’ section, and assistance with post-submission revisions. This assistance was funded by Lundbeck, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Medical writing assistance was funded by Lundbeck, Italy.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare the following conflicts of interest. Andrea Fagiolini received research grants and/or honoraria as a consultant to and/or participant on advisory boards from Angelini, Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Lundbeck, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda and Roche.

Allan H. Young is employed by King’s College London, is an Honorary Consultant to the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM), has received fees for paid lectures and advisory boards for all major pharmaceutical companies with drugs used in affective and related disorders, and has no share holdings in pharmaceutical companies. He is a Lead Investigator for the Embolden Study (Astra-Zeneca), the BCI Neuroplasticity Study and the Aripiprazole Mania Study, and is involved in investigator-initiated studies from Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, and Wyeth. In addition, he has received grant funding (past and present) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, USA), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, Canada), National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD, USA), Stanley Medical Research Institute (USA), Medical Research Council (MRC, UK), Wellcome Trust (UK), Royal College of Physicians (Edinburgh), British Medical Association (BMA, UK), UBC-VGH Foundation (Canada), Western Economic Diversification Canada (WEDC, Canada), CCS Depression Research Fund (Canada), Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR, Canada), and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR, UK).

Giuseppe Maina received grant funding, consulting fees and reimbursements from Lundbeck Italia, Otsuka, Pfizer Italia, Janssen Cilag, and Astra Zeneca.

Anna Coluccia, Alessandro Cuomo, Arianna Goracci, and Rocco N. Forgione declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fagiolini, A., Coluccia, A., Maina, G. et al. Diagnosis, Epidemiology and Management of Mixed States in Bipolar Disorder. CNS Drugs 29, 725–740 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-015-0275-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-015-0275-6