Abstract

Tacrolimus is a pivotal immunosuppressant agent used in solid-organ transplantation. It was originally formulated for oral administration as Prograf®, a twice-daily immediate-release capsule. In an attempt to improve patient adherence, retain manufacturer market share and/or reduce health care costs, newer once-daily prolonged-release formulations of tacrolimus (Advagraf® and Envarsus® XR) and various generic versions of Prograf® are becoming available. Tacrolimus has a narrow therapeutic index. Small variations in drug exposure due to formulation differences can have a significant impact on patient outcomes. The aim of this review is to critically analyse the published data on the clinical pharmacokinetics of once-daily tacrolimus in solid-organ transplant patients. Forty-three traditional (non-compartmental) and five population pharmacokinetic studies were identified and evaluated. On the basis of the stricter criteria for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs, Prograf®, Advagraf® and Envarsus® XR are not bioequivalent [in terms of the area under the concentration–time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) or the minimum concentration (C min)]. Patients may require a daily dosage increase if converted from Prograf® to Advagraf®, while a daily dosage reduction appears necessary for conversion from Prograf® to Envarsus® XR. Prograf® itself, or generic immediate-release tacrolimus, can be administered in a once-daily regimen with a lower than double daily dose being reported to give 24-h exposure equivalent to that of a twice-daily regimen. Intense clinical and concentration monitoring is prudent in the first few months after any conversion to once-daily tacrolimus dosing; however, there is no guarantee that therapeutic drug monitoring strategies applicable to one formulation (or twice-daily dosing) will be equally applicable to another. The correlation between the tacrolimus AUC0–24 and C min is variable and not strong for all three formulations, indicating that trough measurements may not always give a good indication of overall drug exposure. Further investigation is required into whether the prolonged-release formulations have reduced within-subject pharmacokinetic variability, which would be a distinct advantage. Whether the effects of factors that influence tacrolimus absorption and pre-systemic metabolism (patient genotype status; gastrointestinal disease and disorders) and drug interactions differ across the formulations needs to be further elucidated. Most pharmacokinetic comparison studies to date have involved relatively stable patients, and many have been sponsored by the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing the new formulations. Larger randomized, controlled trials are needed in different transplant populations to determine whether there are differences in efficacy and toxicity across the formulations and whether formulation conversion is worthwhile in the longer term. While it has been suggested that once-daily administration of tacrolimus may improve patient compliance, further studies are required to demonstrate this. Mistakenly interchanging different tacrolimus formulations can lead to serious patient harm. Once-daily tacrolimus is now available as an alternative to twice-daily tacrolimus and can be used de novo in solid-organ transplant recipients or as a different formulation for existing patients, with appropriate dosage modifications. Clinicians need to be fully aware of pharmacokinetic and possible outcome differences across the different formulations of tacrolimus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Tacrolimus is a key immunosuppressant for solid-organ transplant recipients, with two new once-daily dosage formulations now developed. |

On the basis of the criteria for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs, Prograf® (twice-daily tacrolimus), Advagraf® and Envarsus® XR (both once-daily tacrolimus formulations) are not bioequivalent, and inadvertent formulation changes can lead to serious patient harm. |

The correlation between the tacrolimus area under the concentration–time curve from 0 to 24 h and the minimum concentration is variable and is not strong for all three formulations; trough measurements may not always give a good indication of overall drug exposure, and patients changing formulations require close pharmacokinetic and clinical monitoring. |

1 Introduction

Tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, was introduced in the early 1990s as an alternative to cyclosporine for preventing rejection after solid-organ transplantation. It is now widely used, with over 90 % of newly transplanted kidney recipients and liver transplant recipients being reported to receive tacrolimus as one of their immunosuppressant medications. According to US Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network data, in 2012, 91.1 % of adult kidney and adult liver transplant recipients were prescribed tacrolimus at the time of transplantation [1].

Tacrolimus was original formulated as Prograf® (Astellas Pharma), an immediate-release hard gelatine capsule available in strengths of 0.5, 1 and 5 mg. At least six companies in the USA now manufacture generic versions of this capsule (Accord Healthcare, Dr. Reddy Labs, Panacea Biotec, Sandoz, Strides Pharma and Mylan) [2]. Tacrolimus in the Prograf® formulation (and associated generic versions) has been associated with low and variable bioavailability [3, 4]. Prograf® capsules are usually administered twice daily, every 12 h (although for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, once-daily administration is advised). Significant between- and within-subject variability in absorption and between-subject variability in metabolism (the main mechanism for clearance) of tacrolimus has been reported [3]. Trough blood concentrations are measured in clinical transplantation practice, and subsequent tacrolimus doses are adjusted to maintain transplant recipients within defined therapeutic concentration ranges. These ranges vary according to the transplant type and the time after transplantation [3]. Concomitant medication can also influence blood concentrations of tacrolimus, so any changes in medication regimens need to be accompanied by increased monitoring [3]. Concentrations 12 h after the night-time dose of the immediate-release formulation are generally measured, and these morning trough concentrations have been used to develop the target concentration ranges for tacrolimus. There is diurnal variation in the concentration–time profile of tacrolimus, with peaks after the evening dose being lower and more prolonged [5, 6].

Coinciding with the patent expiry for tacrolimus in the originator formulation of Prograf® in the USA in 2008 (2009 in Europe; 2010 in Japan), a once-daily prolonged-release dosing formulation of tacrolimus was developed [7]. The same pharmaceutical company that manufactures Prograf®, Astellas Pharma, developed a range of formulations showing modified release of tacrolimus, and MR-4 was chosen for further development into the once-daily product (Advagraf® is the brand name used in the UK, Canada and Europe). Tacrolimus formulated as Advagraf® is available in a prolonged-release hard gelatine capsule in strengths of 0.5, 1, 3 and 5 mg. In the Advagraf® capsule, tacrolimus is mixed with ethylcellulose, hypromellose and lactose to form intermediate-sustained-release granules. The sustained-release character of the granules is imparted by the ethylcellulose, which controls the rate of permeation of water into the granules [8]. Advagraf® was reported by its manufacturer to give a prolonged time to maximum concentration (T max), with an area under the blood concentration–time curve (AUC) from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) similar to that of twice-daily immediate-release tacrolimus [8–10]. This product (using a number of brand names) received regulatory approval in various jurisdictions from 2008 onwards. Other brand names used by Astellas Pharma for this same formulation of tacrolimus include Prograf-XL® (in Australia), Graceptor® (in Japan) and Astagraf XL® (in the USA). Generic versions of Advagraf® are also starting to be developed [11]. When patients are switched from Prograf® (or its various generic versions) to Advagraf®, a milligram-per-milligram daily dose change is currently recommended by the manufacturer.

Presently, a second once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus formulation is going through the regulatory approval process. Veloxis Pharmaceuticals has developed Envarsus® XR, also referred to as LCP-Tacro. Envarsus® XR is being manufactured as 0.75, 1 and 4 mg prolonged-release tablets. Envarsus® XR is designed to be administered once daily and uses MeltDose® technology to achieve its modified release [12]. During manufacturing, the particle size of tacrolimus is reduced to a molecular level by heating it to create a ‘melt’ solution. A patented nozzle is then used to spray the atomized drug onto an inert particulate carrier, which, on solidification, becomes a granulate. Granulates are then compressed into tablets, which are designed to enable more controlled, steady drug dissolution [13]. This formulation is stated to have higher bioavailability than Prograf®, and the manufacturer does not claim bioequivalence between the two formulations. Presently, when patients are changing from conventional twice-daily tacrolimus capsules (Prograf® or generic manufacturer competitors), only 70 % of the dose (milligram per milligram) is recommended.

Tacrolimus has a narrow therapeutic index. Small variations in drug exposure due to formulation differences can have a significant impact on patient outcomes [4]. The aim of this review is to critically analyse the published data on the clinical pharmacokinetics of once-daily tacrolimus in solid-organ transplant patients, discussing clinical implications and areas where further research is required.

2 Methods

Literature searches were conducted in Science Citation Index (ISI Web of Knowledge) and PubMed Medline (last search: 30 March 2015) with the keywords ‘tacrolimus’, ‘pharmacokinetics’ and ‘once’, searching the years 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007 and 2006. All article titles thus retrieved were then searched; any relevant to the aim of this review were compiled into an Endnote Library, and electronic copies of the full papers were obtained. Bibliographies of relevant papers were reviewed manually to identify additional potentially relevant studies. Data were extracted from these papers and compiled into tables. These data were then critiqued.

As there are now a number of oral formulations of tacrolimus, to distinguish between them, they are referred to by brand name if specified in the original study. References retrieved from bibliographies were included if relevant to once-daily dosing of any formulation of tacrolimus, even if prior to the development of the modified-release (MR) formulations (e.g. see Hardinger et al. [5]).

A previous review compiled the data around the bioequivalence of Advagraf® versus Prograf® until mid-2011, but information is presented in a somewhat different way in the present review, not repeating the same data syntheses [14].

3 Results

Eighty-seven unique references were found in the searches, with a further nine found by searches of bibliographies, and full copies of all relevant publications were retrieved. Summaries of the relevant retrieved pharmacokinetic studies, those publications including original data, were compiled into tables and critiqued.

3.1 Traditional Pharmacokinetic Studies

Forty-three traditional (non-compartmental) studies investigating tacrolimus pharmacokinetics following once-daily dosing of the prolonged-release formulations were identified. Key methodological features and results from these studies are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. Studies that compared once- and twice-daily formulations in different patient cohorts have not been included in the tables if they did not report AUC0–24 values.

Correlations between tacrolimus AUC0–24 and minimum concentrations (C min) are displayed in Table 3, and between- and within-subject variability estimates associated with these parameters are summarized in Table 4. Most studies compared tacrolimus AUC0–24, maximum concentration (C max) and/or C min across the formulations; some also looked at dosage adjusted AUC0–24, C max and/or C min, and how tacrolimus dosing changed following conversion. Some studies looked at the correlation between tacrolimus AUC0–24 and C min and graphically compared once-daily- and twice-daily-based pharmacokinetic profiles. A few studies reported whether within- and between-subject variability were different across the formulations and investigated whether there were any differences in the influence of cytochrome P450 3A5 (CYP3A5) genotype status (rs number: 776746) on tacrolimus pharmacokinetics when patients were converted between the formulations.

In terms of their design, most studies were either (1) an open-label conversion study (the study compared the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in the same patients converted from a twice-daily formulation to a once-daily formulation); or (2) a randomized comparator study (the study compared the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in two separate patient groups, one group receiving the twice-daily formulation and the other group receiving the once-daily formulation). The conversion studies were generally conducted in the later post-transplantation period, while many of the comparator studies were performed immediately post-transplantation. Some studies involved tacrolimus trough concentration measurement only, while others performed rich pharmacokinetic profiling, taking multiple blood samples over one dosing interval.

In studies where it was clear that Prograf® and Advagraf® were being compared, conversion from Prograf® to Advagraf® on a milligram-per-milligram daily dose basis often resulted in reduced tacrolimus exposure and increased dosage requirements, with this being notable in some of the patients. A 10–30 % decrease in exposure in this situation appeared to be common. In most, but not all, studies, the mean steady-state ratios of Advagraf® to Prograf® for AUC0–24 and C min had 90 % confidence intervals (CIs) within the 80–125 % range that typically defines bioequivalence, but often outside the tighter 90–111.11 % reference range for AUC0–24 that is now recommended for tacrolimus by the European Medicines Agency [59]. One study reported that the increase in tacrolimus dosage requirements following conversion from Prograf® to Advagraf® may be more pronounced in patients switched within 3 months of transplantation than in patients switched more than 1 year after surgery [17]; however, the retrospective design of that study was somewhat limiting. In two studies where it was clear that patients had been converted from Prograf® to LCP-Tacro (Envarsus® XR), an approximately 30 % lower dose of LCP-Tacro resulted in exposure similar to that seen with twice-daily tacrolimus capsules [12, 39].

Several studies looked at the correlation between tacrolimus AUC0–24 and C min following use of the once-daily extended-release formulations (Table 3). Reported correlations (r 2) ranged from 0.24 to 0.94. There was not always a strong indication of association (with sometimes only 60 % of variability explained). In one study involving 26 stable renal transplant recipients, tacrolimus trough measurements taken from 26 to 32 h after Advagraf® dosing were found to have a correlation with tacrolimus AUC0–24 similar to that of a measurement taken 24 h after dosing [58]. The authors suggested that in patients in whom it was impractical to get a 24-h trough measurement because of an afternoon outpatient clinic appointment, a later ‘delayed’ trough value may still be useful, although the trough target range would need to be lowered accordingly.

Some studies graphically compared mean pharmacokinetic profiles across the formulations. Typical profiles of Prograf® versus Advagraf® and Prograf® versus LCP-Tacro (Envarsus® XR) are displayed in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. In comparison of concentration–time plots between Prograf® and Advagraf® (e.g. see Refs. [19, 27–29, 37, 38, 47–49]), Advagraf® therapy generally appeared to be associated with a slightly longer T max and a lower C min (following 1:1 daily dose conversion). Advagraf® had a flatter profile than Prograf®, with a similar or lower C max. In comparison of concentration–time plots between Prograf® and Envarsus® XR profiles (in two studies only, both supported by Veloxis Pharmaceuticals) [12, 39], Envarsus® XR had a flatter pharmacokinetic profile characterized by lower peak–trough fluctuations, compared with Prograf®. C max, C max/C min ratio, percentage fluctuation and percentage swing were found to be significantly lower and T max significantly longer (following 1:0.7 daily dose conversion).

Top panel whole-blood tacrolimus concentration–time curves in renal transplant patients taking tacrolimus (Tac) twice daily (BID), shown by white circles (n = 47), and once daily (QD), shown by black circles (n = 25). Each data point and bar represent the mean ± standard deviation (reproduced from Niioka et al. [27], with permission). Bottom panel mean pharmacokinetic profiles of Tac BID and Tac QD (reproduced from Stifft et al. [28], with permission)

Mean whole-blood tacrolimus concentrations versus time in patients on days 7, 14 and 21 (reproduced from Gaber et al. [12], with permission)

Interestingly, one study compared Prograf® administered in the usual twice-daily dosage with the same Prograf® formulation administered once daily (reproduced in Fig. 3) [5]. Eighteen stable renal transplant recipients were given Prograf® once daily in the morning at 67, 85 and 100 % of their normal twice-daily dose. Prograf® given once daily at 85 % of the twice-daily dose was found to achieve a pharmacokinetic profile reasonably comparable to that of twice-daily dosing, with a similar C min but higher C max, compared with those observed with twice-daily Prograf® [5].

Tacrolimus blood concentration–time profile of a representative subject from each dosing regimen. In the 67 % group (top panel), the area under the blood concentration–time curve (AUC) ratio between twice-daily (BD) and once-daily (QD) dosing was 0.680. In the 100 % group (bottom panel), the AUC ratio between BD and QD dosing was 1.227. In the 85 % group (middle panel), the mean AUC ratio between BD and QD exposure was 1.025, thus predicting the best conversion ratio between QD and BD dosing. Conc concentration (reproduced from Hardinger et al. [5], with permission)

A few studies examined whether between- and/or within-subject variability in pharmacokinetics was different across the formulations. Three studies reported that within-subject variability [percentage coefficient of variation (% CV)] in AUC0–24 or C min decreased significantly following conversion from Prograf® to Advagraf® [28, 35, 43], while two studies could find no significant difference [31, 45]. Conversion from Prograf® to Advagraf® resulted in a significant reduction in within-subject variability in tacrolimus AUC0–24 from 14.1 to 10.9 % (but no reduction in C min) in a study involving 40 stable kidney transplant recipients, assessed using five AUC values for each dosing regimen [28], and a reduction in tacrolimus C min from 14.0 to 8.5 % in a study involving 129 stable kidney transplant recipients [35]. Two studies reported significantly less within-subject variation in exposure after conversion to MR tacrolimus but provided no actual numerical data [43, 60]. Another study reported similar within- and between-subject variability between Prograf® and Advagraf® formulations [31]. No study to date has looked at within-patient variability in exposure to Envarsus® XR.

Factors in these traditional design studies reported to influence the pharmacokinetics of prolonged-release tacrolimus included patient CYP3A5 genotype status [17, 19, 27, 28, 32, 36, 38, 61], age [51], race [57] and time after transplantation [17]. These same factors were also reported to be influential when immediate-release tacrolimus was administered twice daily [3].

Four studies reported that the decrease in tacrolimus exposure observed after conversion from Prograf® to Advagraf® appeared more marked in patients with the CYP3A5*1/*3 genotype (i.e. CYP3A5 expressers) than in those with the CYP3A5*1/*1 genotype (CYP3A5 non-expressers) [19, 27, 36, 61]. In contrast, two studies reported the opposite, that patients with the CYP3A5*3/*3 genotype (CYP3A5 non-expressers) were the ones who experienced the largest decrease in AUC0–24 and/or C min following milligram-per-milligram-based conversion [32, 38]. One study, which reported that conversion from Prograf® to Advagraf® resulted in a significant decrease in within-subject variability in AUC0–24, found that this decrease was numerically greatest in patients with the CYP3A5*1 genotype (% CV down from 18.2 to 12.8 % on conversion in CYP3A5 expressers versus a decrease from 12.6 to 10.2 % on conversion in CYP3A5 non-expressers) [28].

One study involving 97 adult renal transplant recipients compared oral administration of Prograf® and Graceptor® (Advagraf®) with intravenous administration [61]. Forty-seven patients received Prograf® capsules twice daily, starting 2 days prior to surgery, and 50 patients received Graceptor® capsules once daily, starting 2 days prior to surgery. This was followed by a 24-h continuous intravenous infusion of tacrolimus for the first 3 days after surgery in all patients. Tacrolimus bioavailability was calculated on the basis of AUC0–24 values after intravenous and oral administration in the same recipients (with correction for dosage). The median relative bioavailability of tacrolimus for recipients with the CYP3A5*1 or CYP3A5*3/*3 alleles was significantly lower for patients on Graceptor® (median 9.1 and 15.4 %, respectively) than for patients on Prograf® (median 12.6 and 19.3 %, respectively) [61]. These data suggest that between-subject variability in pharmacokinetics is due to CYP3A5 polymorphism, as well as the dosage form, with tacrolimus absolute bioavailability being lowest in those expressing CYP3A5*1 and receiving Graceptor® [61].

Data from healthy volunteer studies that are available for Advagraf® have been summarized and tabulated previously [14]. These studies (single- and multiple-dose) showed that, in comparison with the Prograf® formulation, C max was lower, T max was mostly longer and AUC [extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞)] was lower by about 10–20 % [14]. An early review of the pharmacokinetics of MR tacrolimus revealed that the formulation, known then as MR-4, was one of four developed and tested by Astellas Pharma, also citing ‘data on file’ with the pharmaceutical company [10]. Healthy volunteer data were stated to reveal a lower C max but a similar AUC0–24 with the MR-4 formulation compared with Prograf® [10].

3.2 Population Pharmacokinetic Studies

Five population studies investigating tacrolimus pharmacokinetics following once-daily dosing of the prolonged-release formulations were identified. Key methodological features and results from these studies are displayed in Tables 5 and 6.

All population pharmacokinetic studies to date have involved the Advagraf® formulation. Four of these studies were conducted in adult kidney transplant recipients, and one was conducted in paediatric kidney transplant recipients. All studies involved rich pharmacokinetic profiling, taking multiple blood samples over one dosing interval. Some were conducted in de novo patients in the immediate post-transplantation period, and others were conducted in stable patients who had been converted to the once-daily prolonged-release formulation. None included more than 50 patients receiving Advagraf®, and in all but two studies, the final model was not evaluated in a separate patient group.

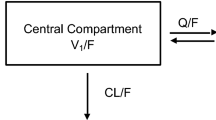

To describe the complex drug release and absorption characteristics of Advagraf®, an Erlang model [with three transit compartments connected by the same transfer rate constant (k tr)] or a double-gamma absorption model has been most commonly used. Both one- and two-compartment models were employed to describe tacrolimus disposition, with elimination always modelled as a first-order process. Between-subject variability in apparent clearance [clearance divided by bioavailability (CL/F)] ranged from 28 to 35 % (based on three studies), and between-subject variability in the absorption transfer rate constant (k tr) in the Erlang models ranged from 24 to 52 % (based on two studies).

One study simultaneously modelled pharmacokinetic data from Prograf® and Advagraf® formulations [63]. Differences between the formulations were mostly observed in the absorption phase. In this study, the average absorption of Advagraf® was found to be slower and more variable than that of Prograf®. Within-subject variability in CL/F and k tr (based on combined data from both formulations) was estimated to be 31 and 33 %, respectively 63].

Factors in these population pharmacokinetic studies that were reported to influence the pharmacokinetics of once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus included patient CYP3A5 genotype status, haematocrit, the assay used for drug measurement and patient weight. These same factors have also been reported to be influential when tacrolimus is administered twice daily [3].

Interestingly, a further population pharmacokinetic study has been conducted on the basis of Prograf® administered in either a once-daily regimen (n = 16) or a twice-daily regimen (n = 15) [67]. A higher absorption rate and a larger volume of distribution were observed for the once-daily dosing group. The authors provided no explanation for this but did suggest that on the basis of the pharmacokinetic data that were obtained, once-daily dosing could also be an option with Prograf® therapy.

3.3 Efficacy and Safety Studies

Data on the clinical utility of once-daily tacrolimus were recently evaluated in a comprehensive review [68]. The authors of that review examined 17 efficacy and safety studies of once-daily tacrolimus (six in de novo kidney transplant recipients, five in stable kidney transplant recipients, one in both de novo and stable kidney transplant recipients, and five in liver transplant recipients). These studies ranged in design from prospective, double-blind, multicentre, randomized, controlled trials to retrospective, observational studies and involved from 33 to 976 subjects. The vast majority of studies compared Advagraf® and Prograf® treatment. The authors of that review concluded that efficacy studies indicate that once-daily tacrolimus is non-inferior to twice-daily tacrolimus, with a concentration-dependent rejection risk [68]. The biopsy-proven acute rejection rates, though often higher with once-daily tacrolimus, were not statistically higher than those with twice-daily tacrolimus. Graft and patient survival were considered comparable between the formulations examined.

Some smaller studies included in that review suggested that once-daily tacrolimus may have favourable effects on blood pressure, the lipid profile and glucose tolerance [68]. For the most part, studies that showed improvement in glucose metabolism with once-daily tacrolimus attributed this to lower C max values achieved with the once-daily formulation [68]. Few studies examined in that review had drug safety as a primary end point. A recent retrospective study involving 129 liver transplant recipients also suggested a potential benefit to renal function following conversion, and it was speculated that this could possibly be due to improved patient adherence [60].

A very recent retrospective analysis of the European Liver Transplant Register (not included in the aforementioned review paper) suggested that there may be significant improvements in long-term graft and patient survival in patients treated with Advagraf® compared with Prograf® in primary liver transplant recipients over 3 years of treatment [69]. The study involved 4367 patients in total (528 in the Advagraf® treatment group and 3839 in the Prograf® treatment group, respectively). Prograf® treatment was significantly associated with an inferior graft risk (risk ratio 1.81, P = 0.001) and patient survival (risk ratio 1.72, P = 0.004) in multivariate analysis [69]. This was a retrospective registry evaluation with a number of limitations. Patients in the two treatment groups sometimes received different concurrent immunosuppressant agents; were enrolled in other clinical trials (which may have introduced bias in terms of patient selection); and were stratified to their treatment group on the basis of the tacrolimus formulation they received in the first month post-transplantation, and remained in this allocated group regardless of any change in immunosuppression during the 3-year follow-up period [69].

Another very recent multicentre, 24-week, randomized trial (the DIAMOND study) compared the effects of different Advagraf® dosing regimens on renal function in adult de novo liver transplant recipients [70]. Patients were randomized to one of three treatment arms. Patients in arm 1 received Advagraf® at an initial dose of 0.2 mg/kg/day; patients in arm 2 received Advagraf® at an initial dose of 0.15–0.175 mg/kg/day plus basiliximab induction therapy; and patients in arm 3 received Advagraf® at an initial dose of 0.2 mg/kg/day, delayed to day 5, plus basiliximab. All patients received mycophenolate mofetil, and maintenance steroids were not used. A total of 615 patients completed the study [70]. Patients in arms 2 and 3 (with lower or delayed tacrolimus exposure initially) had a significantly higher estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at week 24, compared with patients in arm 1 (eGFR values: 67.4 mL/min in arm 1, 76.4 mL/min in arm 2, 73.3 mL/min in arm 3) [70]. Interestingly, patients in arm 2 (who had lower tacrolimus exposure initially) also had significantly less biopsy-confirmed acute rejection (BCAR) at week 24 when compared with the other arms (BCAR values: 17.8 % in arm 1, 12.1 % in arm 2, 16.8 % in arm 3). Adverse events were comparable between all treatment regimens [70]. The authors of this study suggested that ensuring that tacrolimus exposure with Advagraf® therapy in the immediate post-transplantation period is not too high may be critical in maintaining renal function in the longer term.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

Prescribing of the immunosuppressant agent tacrolimus is becoming more complex. To improve adherence, retain market share and reduce costs, newer once-daily prolonged-release formulations and various generic versions of the market leader product are becoming available. With narrow-therapeutic-index drugs such as tacrolimus, small variations in drug exposure due to formulation differences can have significant impacts on clinical outcomes [4]. Prograf®, Advagraf® and Envarsus® XR have different drug release characteristics and are not directly interchangeable on a milligram-per-milligram daily dosing basis in all individuals.

4.1 Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic studies in the literature of once-daily tacrolimus dosing have focussed on the new formulations of tacrolimus developed to give a modified release rather than administering standard-release tacrolimus (Prograf® or generics) once daily to transplant recipients. This latter strategy deserves more attention as a viable alternative.

In this review, 43 traditional and five population pharmacokinetic studies were identified that evaluated the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in prolonged-release formulations. It should be noted that morning rather than afternoon or evening administration of the once-daily prolonged-release formulations was examined in these studies. Unfortunately, these studies did not always describe how the relevant pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g. AUC) were calculated (presumably, the linear trapezoidal method was used in most of the traditional studies to estimate AUC). In the traditional studies, C max and C min reported from available observations were dependent on the time points actually chosen for collection (e.g. the true C max may have been missed). C min could have been at 0 h post-dose (C 0) or at 12 h post-dose (C 12) (with twice-daily dosing), or at 24 h post-dose (C 24) (with once-daily dosing). Various assays were used for tacrolimus drug measurement, with many studies using the optimal, specific and sensitive liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) techniques, but a significant number of studies used the relatively less specific but technologically simpler immunoassays [71, 72]. Thus, actual reported concentrations and exposures measured using these immunoassays would appear higher than those from studies using LC–MS/MS assays. Some of the pharmacokinetic studies failed to specify which prolonged-release formulation of tacrolimus was used, with the assumption being that most would have been Advagraf®. In some studies, it was not entirely clear which formulation was assessed—for example, in a 2005 publication, an MR tacrolimus formulation was used, then manufactured by Fujisawa, but it is not clear whether this is identical to the currently marketed Advagraf® [15]. In the traditional pharmacokinetic studies, essentially all comparisons of the once-daily formulations were specified as being against the twice-daily formulation market leader (Prograf®), but there are now also generic formations of twice-daily tacrolimus, and it was not clear whether some of the later studies could perhaps have used one of these as a comparator. Population pharmacokinetic models of Advagraf® have been based on relatively small subject numbers and have generally not been externally validated. To date, there has been no direct pharmacokinetic comparison of the two once-daily prolonged-release formulations Advagraf® and Envarsus® XR, and no population pharmacokinetic model has yet been developed for Envarsus® XR.

Conversion from Prograf® to Advagraf® on a milligram-per-milligram daily dosing basis, as recommended, is unlikely to be as straightforward as suggested by the manufacturer [8]. Patients may require a dosage increase if converted from Prograf® to Advagraf®, while a dosage reduction appears necessary if conversion from Prograf® to Envarsus® XR is undertaken. Studies have reported lower or equivalent AUC0–24 and C min values with the Advagraf® formulation compared with the Prograf® formulations, with up to one quarter to one half of transplant recipients in some studies requiring dosage adjustment (mostly an increased dose with Advagraf®) after conversion to achieve equivalent exposure. This could have important clinical implications, possibly leading to rejection, morbidity and mortality, if lower exposure is not noted and dosage adjustment implemented. Only two studies to date have looked at conversion from Prograf® to Envarsus® XR in transplant recipients; both involved ‘stable’ adult patients and were funded by the manufacturer. In both of these studies, a mean conversion ratio of 0.71 gave similar AUC0–24 and C min values compared with Prograf®, with lower C max values. It should be noted that the margins for bioequivalence have been reduced for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs [59]. Under the new criteria, neither Prograf® (and its generic variations) and Advagraf®, nor Prograf® and Envarsus® XR, would be considered bioequivalent [14, 73].

Close monitoring of tacrolimus concentrations is vital following conversion between formulations, as a substantial number of patients require a dosage adjustment to achieve similar tacrolimus trough concentrations, assuming that these troughs are still relevant to total tacrolimus exposure. There is no guarantee that a therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) strategy that is applicable to one formulation will be equally applicable to another. The correlation between tacrolimus AUC0–24 and C min is variable and is not always strong for all three formulations, indicating that trough measurements may not always give a good indication of overall drug exposure. AUC, rather than trough concentration measurement, is likely to better characterize patient exposure to tacrolimus [74], but it has not been clinically proven that a better patient outcome could be obtained with AUC-based TDM than with C min-based TDM for the once- or twice-daily formulations, as no dedicated randomized clinical trials have been performed with this aim [62]. Limited sampling strategies developed for one formulation to predict tacrolimus AUC are unlikely to be applicable to another.

Interestingly, one traditional and one population pharmacokinetic study have investigated giving Prograf® once daily rather than twice daily [5, 67], with both reporting that once-daily dosing could also be an option with Prograf® therapy [5, 67]. The rationale for the earlier of these studies, as given by the authors, was that tacrolimus exhibits time-dependent kinetics, with a lower C max after evening doses due to a circadian variation or due to food intake, and that a higher C max has not been reported to be associated with a higher risk of adverse events [5, 75]. Similar circadian variations in tacrolimus pharmacokinetics have also been reported in liver transplant recipients [75]. Some of the comparison studies (following conversion from twice-daily to once-daily dosing) have also shown the diurnal variation typical after the immediate-release formulation [6, 27, 28]. This diurnal variation, and the results from administration of Prograf® once daily, must raise questions about any benefit of giving a tacrolimus prolonged-release dosage form and whether a very similar pharmacokinetic profile could be achieved simply by administration of a larger immediate-release dose once daily each morning. This approach deserves further study, as Prograf® (and its generic equivalents) are now widely available, cheaper than prolonged-release formulations and already registered in many jurisdictions.

When using a prolonged-release formulation, as opposed to an immediate-release formulation, more of the drug is likely to be released in the distal regions of the gastrointestinal tract. Tacrolimus was shown to be able to be absorbed from the duodenum to the colon in six healthy white male subjects [76]. A change in the primary site of release of tacrolimus could potentially cause differences in the impact of gastrointestinal metabolic enzymes and gastrointestinal motility (affected by conditions such as diarrhoea or diabetes) on tacrolimus pharmacokinetics with the different formulations.

CYP3A4 and 3A5 isoenzymes are largely responsible for tacrolimus metabolism in both the liver and the gastrointestinal tract. CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 are not uniformly distributed in the gastrointestinal tract, with greater expression in the small intestine than in the colon [77–79]. Genetic polymorphisms in proteins involved in tacrolimus processing can influence a patient’s exposure to this drug [80–82]. It is not clear whether there is any difference in the influence of genetic polymorphism in CYP3A5 on the pharmacokinetics of Advagraf® compared with Prograf® [3, 19, 83, 84]. No study to date has looked at the confounding influence of other genetic factors [CYP3A4, ABCB1 and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)–CYP oxidoreductase (POR) polymorphisms], or the possible influence of CYP3A5 genotype status on patient dosage requirements for Prograf® versus Envarsus® XR.

Solid-organ transplant recipients invariably receive multiple immunosuppressants. Patients on tacrolimus are likely to be prescribed concomitant mycophenolate (or, less commonly, azathioprine), prednisone/prednisolone and perhaps other immunosuppressant classes (e.g. if rejection occurs), as well as antihypertensive agents, anti-infective drugs, cholesterol-lowering medications, drugs to treat osteoporosis and drugs for gastrointestinal intolerance. Drug interactions associated with usage of twice-daily oral formulations of tacrolimus are also likely to be significant during usage of once-daily prolonged-release formulations [3]. It is not known whether there are any additional pharmacokinetic differences across the formulations during administration of interacting drugs—for example, associated with absorption, gastrointestinal transportation or pre-systemic metabolism of tacrolimus. One small study, involving 20 stable renal transplant recipients, examined mycophenolic acid exposure following standard twice-daily tacrolimus usage versus once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus usage, and concluded that although this mycophenolate AUC difference was 10 % greater with the twice-daily formulation, it did not achieve statistical significance [85].

There is growing evidence that increased within-subject variability in tacrolimus pharmacokinetics is associated with poorer clinical outcomes, including graft failure and late rejection [4, 86–88]. Further investigation is required into whether the prolonged-release formulations have reduced within-subject pharmacokinetic variability. There have been claims that 24-h trough concentrations are more ‘stable’ with once-daily dosing than with twice-daily dosing and are able to be maintained with few dosage adjustments for up to 1 year following liver transplantation or 2 years following renal transplantation. However, critiques of the studies from which these conclusions were drawn have identified a number of problems. For example, one study in liver transplant recipients found that there was a significant decline in trough tacrolimus concentrations (implying increased CL/F with the once-daily formulations—either increased clearance or a decreased fraction of dose absorbed) when patients were switched from twice-daily to once-daily dosing with Advagraf® [41]. This necessitated dosage increases, with nearly one third of the recipients requiring dosage increases at week 2 (with two people needing >100 % dosage increases) [41]. One study in de novo, older renal transplant recipients, directly comparing the twice-daily formulation (n = 12) with a once daily formulation (n = 14) in a randomized design, found that similar daily doses of tacrolimus were required to achieve target trough concentrations [16]. One retrospective chart review of 26 renal transplant recipients receiving Advagraf® after transplantation found they needed up to 50 % higher tacrolimus doses (in milligrams per kilogram of body weight) to maintain target trough tacrolimus concentrations equivalent to those in a group of 26 historical controls who received twice-daily Prograf® after their renal transplantation [89]. However, this study design was not strong, as randomization was not used to assign dosage forms and there could have been systematic differences between the historical controls and the patients chosen to receive once-daily tacrolimus [89]. A further retrospective review of 284 renal allograft recipients who had changed from twice-daily tacrolimus to the once-daily Advagraf® formulation found that in over 50 % of patients, daily doses needed to be increased after conversion [17]. In more than one third of patients who switched, trough tacrolimus concentrations decreased by more than 20 % [17]. Despite these dosage increases, the average trough concentrations remained almost 10 % lower after conversion to once-daily dosing [17]. Another study involving 82 stable kidney transplant recipients found that only five patients needed a later dose adjustment after converting from Prograf® to Advagraf®; however, that study also found that in the 61 patients with no dosage adjustment, trough concentrations decreased significantly (by about 15 %) in the first week after the switch [18]. It is not clear why these recipients did not have their dosages increased to adjust to the same target trough tacrolimus concentrations as previously. None of these studies support the contention that fewer dosage adjustments are required for once-daily as compared with twice-daily dosing of tacrolimus, so care needs to be taken to critique the studies that claim specific advantages for the MR tacrolimus formulations.

Differences between peak and trough concentrations do appear to be lessened by prolonged-release formulations, but whether this is an advantage for a calcineurin inhibitor or not is unclear. For the Envarsus® XR formulation in renal transplant recipients, the percentage fluctuation [100 × (C max − C min)/C av] (where C av is the average concentration) and percentage swing [100 × (C max − C min)/C min) were both reported to be significantly lower than after the Prograf® formulation [12]. However, whether a 100–110 % swing is clinically different from a 175 % swing is not clear, especially as no effect of formulation on adverse events was observed in that study [12].

It should also be noted that many of the pharmacokinetic studies to date have involved ‘healthy’, stable transplant recipients, with many exclusions for more complex individuals (e.g. heart transplant recipients, all with stable trough tacrolimus concentrations of 5–15 ng/mL; none with a history of adverse events, acute rejection in the last 3 months or any liver function test abnormalities [50]; similar exclusions applied for a study on liver transplant recipients [39]). Selection bias may result because of these strict criteria. Interestingly, one study needed 16 centres in Europe, Canada and the USA to recruit 45 completed patients [50]; another needed 12 centres to recruit 59 liver transplant recipients [39]. Many patients were excluded in some studies because they did not provide full evaluable data sets (e.g. from 85 down to 45 evaluable patients [50]).

One study did look at elderly renal transplant recipients receiving grafts from extended-criteria deceased donors, and they were randomized prior to transplantation to receive either the once-daily or twice-daily tacrolimus formulations. Similar AUCs were found after 3 and 21 days in both groups, and similar doses were required to achieve the target trough concentrations up to 6 months after transplantation [16]. However, the small numbers in this study could mean that the true differences between the groups were missed because of the known large between- and within-subject variability in the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus [16].

Other pharmacokinetics-related questions not yet answered may arise in clinical practice. For example, diarrhoea is reported to dramatically increase patients’ exposure to tacrolimus given in the Prograf® formulation [90], but its influence on drug absorption during use of the prolonged-release formulations is unknown. Clinicians have been known to open Prograf® capsules and give their contents via the nasogastric tube; it is not known whether this is possible with Advagraf®, and it is likely that Envarsus® XR is not crushable.

4.2 Pharmacodynamics

The vast majority of efficacy and safety studies examining once-daily tacrolimus regimens to date have not looked at long-term transplantation outcomes, have not involved paediatric patients or transplant groups other than kidney and liver recipients, and have involved Advagraf® rather than the Envarsus® XR formulation. Non-Caucasians and recipients with elevated immunological risk have been under-represented in studies to date. As once-daily tacrolimus becomes more frequently utilized in clinical practice, more studies on efficacy and drug safety with long-term use need to be conducted in order to better understand drug effects and refine drug administration among transplant patients [68].

No severe adverse effects have been reported following 1:1 conversion of Prograf® to Advagraf®, although the long-term outcomes associated with possible decreased trough concentrations are unknown. Lack of a difference in acute rejection rates does not preclude the possibility of differences in subclinical graft damage that could compromise lifelong survival [73]. Alternatively, lower tacrolimus C max values associated with the once-daily prolonged-release formulations might help to decrease the incidence of hyperglycaemia, hyperlipidaemia and nephrotoxicity [68, 73]. More data and longer follow-up are needed to unambiguously establish the clinical equivalence or not of the various formulations.

4.3 Other Issues: Evidence Around Adherence, Pharmaceutical Company-Sponsored Studies, Problems with Dosage Form Mix-Ups

While there is some evidence that once-daily administration of tacrolimus may improve patient compliance [39, 41, 91]—and in one study, patients stated a preference for once-daily tacrolimus dosing [41]—further studies are required to demonstrate this conclusively. This could be difficult to ascertain with a large number of medications used in transplant recipients (in addition to immunosuppression), including treatment of, and prophylaxis against, adverse events. A recent study used a questionnaire (with 312 responses) in people living with a renal transplant and found that 85 % of those questioned had twice-daily dose times (with two thirds of the group receiving over seven individual drugs) [91]. The rationale and focus just on tacrolimus as an isolated immunosuppressant has been called into question—for example, other immunosuppressants (such as mycophenolate) are dosed at least twice daily; therefore, the total number of daily dosing times for organ transplant recipients is not reduced. Also, any missed doses have a bigger implication for a once-daily medication (equivalent to missing two doses of a twice-daily medication) [73]. It has been pointed out that in the course of a week, if four tacrolimus doses are missed (as an example), this would have the effect of decreasing the intake to less than 45 % (4/7) of the required weekly intake if once-daily dosing was being used, whereas four missed doses of the immediate-release formulation would only decrease the weekly intake by less than a third (4/14) [73]. The authors concluded that ‘the assumption of improved adherence remains to be thoroughly investigated and validated in patients already on a high pill burden’ [73]. In two studies, sponsored by the pharmaceutical company Astellas Pharma, increased treatment satisfaction was reported with regard to the convenience of once-daily dosing of tacrolimus, and adherence was reported as being improved after randomization to once-daily dosing with Advagraf® [92]. One study also performed a cost analysis of switching, showing benefits of changing to a once-daily MR formulation of tacrolimus; however, that study was also sponsored by the pharmaceutical company [87, 93].

In approximately half of the studies examined in this review, the study itself—or at least one of the authors involved—was stated to be supported by the manufacturers of Advagraf® or Envarsus® XR. This proportion may be higher, as full disclosure of potential or apparent conflicts of interest has become necessary only in recent years. Criticisms have been levelled about the introduction of Advagraf® as a once-daily dose form of tacrolimus, just when competition from generic manufacturers was on the horizon for the regular twice-daily formulation [73, 94]. A previous commentary clearly critiqued the early studies purporting to show an easy 1:1 dose swap between formulations (as advocated by the company developing the formulation [95]). Publication delays can also be a problem for ‘familiarization’ studies sponsored by pharmaceutical companies—for example, one study conducted from April 2003 to January 2004 was published only in 2011 [50]. This study formed part of a regulatory dossier and was sponsored and the manuscript ‘approved’ by the company marketing the once-daily formulation [50]. Another study performed in 2003 was published only in 2011 [40], and a further study was a conference presentation in 2008 but reached full publication only in 2014 [39].

A final consideration is the potential for unintended mix-ups between the various tacrolimus formulations, which could cause serious patient harm [96]. The Institute for Safe Medicines Practice Canada reviewed 33 international medication incidents involving a Prograf®/Advagraf® mix-up; in most of these incidents, the mistake occurred during prescribing and/or dispensing. Various suffixes and other descriptors on packaging have been recommended to avoid mix-ups in dosing between the twice-daily and once-daily formulations to try and enhance patient safety [96].

In conclusion, once-daily tacrolimus administration is now available as an alternative to twice-daily administration and can be used de novo in solid-organ transplant recipients, or as a different formulation for existing patients, with appropriate dosage modifications. Clinicians need to be fully aware of pharmacokinetic and possible outcome differences across the different formulations of tacrolimus and need to recognize that they are not directly interchangeable. In all groups of transplant recipients, paediatric and adult, it would seem prudent to increase tacrolimus concentration monitoring during a changeover period between once-daily and twice-daily administration.

References

US Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Scientific registry of transplant recipients. 2012. http://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annual_reports/2012/

US Food and Drug Administration. Approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence equations (orange book). Washington, DC: US Food & Drug Administration; 2014.

Staatz C, Tett S. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(10):623–53.

Johnston A. Equivalence and interchangeability of narrow therapeutic index drugs in organ transplantation. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract. 2013;20(5):302–7. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2012-000258.

Hardinger K, Park J, Schnitzler M, Koch M, Miller B, Brennan D. Pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in kidney transplant recipients: twice daily versus once daily dosing. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(4):621–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00383.x.

Heffron T, Pescovitz M, Florman S, Kalayoglu M, Emre S, Smallwood G, et al. Once-daily tacrolimus extended-release formulation: 1-year post-conversion in stable pediatric liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(6):1609–15. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01803.x.

Reuters. Analysis—Astellas loses patent on key drug, outlook unclear. 2008. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2008/04/08/sppage015-t145114-oishe-idUKT14511420080408. Accessed 1 Apr 2015.

Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian public assessment report for Prograf-XL. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra, Australia. 2010. http://www.tga.gov.au/file/1465/download. Accessed 14 Jan 2015.

Wente MN, Sauer P, Mehrabi A, Weitz J, Büchler MW, Schmidt J, et al. Review of the clinical experience with a modified release form of tacrolimus [FK506E (MR4)] in transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2006;20(Suppl 17):80–4. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00605.x.

Chisholm M, Middleton M. Modified-release tacrolimus. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(2):270–5. doi:10.1345/aph.1E657.

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative. Generics applications under review—April 2014. 2014. http://www.gabionline.net/Generics/General/Generics-applications-under-review-by-EMA-April-2014. Accessed 1 Apr 2015.

Gaber A, Alloway R, Bodziak K, Kaplan B, Bunnapradist S. Conversion from twice-daily tacrolimus capsules to once-daily extended-release tacrolimus (LCPT): a phase 2 trial of stable renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2013;96(2):191–7.

Grinyó JM, Petruzzelli S. Once-daily LCP-Tacro MeltDose tacrolimus for the prophylaxis of organ rejection in kidney and liver transplantations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10(12):1567–79. doi:10.1586/1744666X.2014.983903.

Barraclough K, Isbel N, Johnson D, Campbell S, Staatz C. Once- versus twice-daily tacrolimus: are the formulations truly equivalent? Drugs. 2011;71(12):1561–77.

Alloway R, Steinberg S, Khalil K, Gourishankar S, Miller J, Norman D, et al. Conversion of stable kidney transplant recipients from a twice daily Prograf-based regimen to a once daily modified release tacrolimus-based regimen. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(2):867–70. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.222.

Cabello M, García P, González-Molina M, Díez de los Rios MJ, García-Sáiz M, Gutiérrez C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once- versus twice-daily tacrolimus formulations in kidney transplant patients receiving expanded criteria deceased donor organs: a single-center, randomized study. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(8):3038–40. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.08.008.

de Jonge H, Kuypers D, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y. Reduced C-0 concentrations and increased dose requirements in renal allograft recipients converted to the novel once-daily tacrolimus formulation. Transplantation. 2010;90(5):523–9. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e9feda.

Diez Ojea B, Alonso Alvarez M, Aguado Fernández S, Baños Gallardo M, García Melendreras S, Gómez Huertas E. Three-month experience with tacrolimus once-daily regimen in stable renal allografts. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(6):2323–5. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.048.

Glowacki F, Lionet A, Hammelin J, Labalette M, Provot F, Hazzan M, et al. Influence of cytochrome P450 3A5 (CYP3A5) genetic polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics of the prolonged-release, once-daily formulation of tacrolimus in stable renal transplant recipients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(7):451–9.

Hatakeyama S, Fujita T, Yoneyama T, Koie T, Hashimoto Y, Saitoh H, et al. A switch from conventional twice-daily tacrolimus to once-daily extended-release tacrolimus in stable kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(1):121–3. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.11.022.

Hougardy JM, Broeders N, Kianda M, Massart A, Madhoun P, Le Moine A, et al. Conversion from Prograf to Advagraf among kidney transplant recipients results in sustained decrease in tacrolimus exposure. Transplantation. 2011;91(5):566–9. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3182098ff0.

Iaria G, Sforza D, Angelico R, Toti L, de Luca L, Manuelli M, et al. Switch from twice-daily tacrolimus (Prograf) to once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus (Advagraf) in kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(4):1028–9. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.01.130.

Ma M, Kwan L, Mok M, Yap D, Tang C, Chan T. Significant reduction of tacrolimus trough level after conversion from twice daily Prograf to once daily Advagraf in Chinese renal transplant recipients with or without concomitant diltiazem treatment. Renal Fail. 2013;35(7):942–5. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2013.808134.

Meçule A, Poli L, Nofroni I, Bachetoni A, Tinti F, Umbro I, et al. Once daily tacrolimus formulation: monitoring of plasma levels, graft function, and cardiovascular risk factors. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(4):1317–9. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.03.123.

Midtvedt K, Jenssen T, Hartmann A, Vethe NT, Bergan S, Havnes K, et al. No change in insulin sensitivity in renal transplant recipients converted from standard to once-daily prolonged release tacrolimus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(11):3767–72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfr153.

Nakamura Y, Hama K, Katayama H, Soga A, Toraishi T, Yokoyama T, et al. Safety and efficacy of conversion from twice-daily tacrolimus (Prograf) to once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus (Graceptor) in stable kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(1):124–7. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.11.051.

Niioka T, Satoh S, Kagaya H, Numakura K, Inoue T, Saito M, et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of once- and twice-daily tacrolimus in the early stage after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;94(10):1013–9. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e31826bc400.

Stifft F, Stolk LM, Undre N, van Hooff JP, Christiaans MH. Lower variability in 24-hour exposure during once-daily compared to twice-daily tacrolimus formulation in kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;97(7):775–80. doi:10.1097/01.TP.0000437561.31212.0e.

Tsuchiya T, Ishida H, Tanabe T, Shimizu T, Honda K, Omoto K, et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetics and pathology for low-dose tacrolimus once-daily and twice-daily in living kidney transplantation: prospective trial in once-daily versus twice-daily tacrolimus. Transplantation. 2013;96(2):198–204. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e318296c9d5.

Uchida J, Kuwabara N, Machida Y, Iwai T, Naganuma T, Kumada N, et al. Conversion of stable kidney transplant recipients from a twice-daily Prograf to a once-daily tacrolimus formulation: a short-term study on its effects on glucose metabolism. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(1):128–33. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.11.005.

van Hooff J, Van der Walt I, Kallmeyer J, Miller D, Dawood S, Moosa M, et al. Pharmacokinetics in stable kidney transplant recipients after conversion from twice-daily to once-daily tacrolimus formulations. Ther Drug Monitor. 2012;34(1):46–52. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e318244a7fd.

Wehland M, Bauer S, Brakemeier S, Burgwinkel P, Glander P, Kreutz R, et al. Differential impact of the CYP3A5*1 and CYP3A5*3 alleles on pre-dose concentrations of two tacrolimus formulations. Pharmacogenet Genom. 2011;21(4):179–84. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833ea085.

Wlodarczyk Z, Squifflet JP, Ostrowski M, Rigotti P, Stefoni S, Citterio F, et al. Pharmacokinetics for once- versus twice-daily tacrolimus formulations in de novo kidney transplantation: a randomized, open-label trial. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(11):2505–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02794.x.

Wlodarczyk Z, Ostrowski M, Mourad M, Kramer B, Abramowicz D, Oppenheimer F, et al. Tacrolimus pharmacokinetics of once- versus twice-daily formulations in de novo kidney transplantation: a substudy of a randomized phase III trial. Ther Drug Monitor. 2012;34(2):143–7. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31824d1620.

Wu M, Cheng C, Chen C, Wu W, Cheng C, Yu D, et al. Lower variability of tacrolimus trough concentration after conversion from Prograf to Advagraf in stable kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2011;92(6):648–52. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3182292426.

Satoh S, Niioka T, Kagaya H, Numakura K, Inoue T, Saito M, et al. Pharmacokinetic and CYP3A5 pharmacogenetic differences between once- and twice-daily tacrolimus from the first dosing day to 1 year after renal transplantation. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15(11):1495–506. doi:10.2217/pgs.14.98.

Carcas-Sansuan A, Espinosa-Roman L, Almeida-Paulo G, Alonso-Melgar A, Garcia-Meseguer C, Fernandez-Camblor C, et al. Conversion from Prograf to Advagraf in stable paediatric renal transplant patients and 1-year follow-up. Ped Nephrol. 2014;29(1):117–23. doi:10.1007/s00467-013-2564-y.

Min S, Ha J, Kang H, Ahn S, Park T, Park D, et al. Conversion of twice-daily tacrolimus to once-daily tacrolimus formulation in stable pediatric kidney transplant recipients: pharmacokinetics and efficacy. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(8):2191–7. doi:10.1111/ajt.12274.

Alloway R, Eckhoff D, Washburn W, Teperman L. Conversion from twice daily tacrolimus capsules to once daily extended-release tacrolimus (LCP-Tacro): phase 2 trial of stable liver transplant recipients. Liver Transplant. 2014;20(5):564–75. doi:10.1002/lt.23844.

Fischer L, Trunecka P, Gridelli B, Roy A, Vitale A, Valdivieso A, et al. Pharmacokinetics for once-daily versus twice-daily tacrolimus formulations in de novo liver transplantation: a randomized, open-label trial. Liver Transplant. 2011;17(2):167–77. doi:10.1002/lt.22211.

Beckebaum S, Iacob S, Sweid D, Sotiropoulos G, Saner F, Kaiser G, et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunosuppressant adherence in stable liver transplant patients converted from a twice-daily tacrolimus-based regimen to once-daily tacrolimus extended-release formulation. Transpl Int. 2011;24(7):666–75. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01254.x.

Comuzzi C, Lorenzin D, Rossetto A, Faraci MG, Nicolini D, Garelli P, et al. Safety of conversion from twice-daily tacrolimus (Prograf) to once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus (Advagraf) in stable liver transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(4):1320–1. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.03.106.

Florman S, Alloway R, Kalayoglu M, Lake K, Bak T, Klein A, et al. Conversion of stable liver transplant recipients from a twice-daily Prograf-based regimen to a once-daily modified release tacrolimus-based regimen. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(2):1211–3. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.11.086.

Marin-Gomez LM, Gomez-Bravo MA, Alamo-Martinez JA, Barrera-Pulido L, Bernal Bellido C, Suárez Artacho G, et al. Evaluation of clinical safety of conversion to Advagraf therapy in liver transplant recipients: observational study. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(6):2184–6. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.085.

Sańko-Resmer J, Boillot O, Wolf P, Thorburn D. Renal function, efficacy and safety postconversion from twice- to once-daily tacrolimus in stable liver recipients: an open-label multicenter study. Transpl Int. 2012;25(3):283–93. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01412.x.

Sugawara Y, Miyata Y, Kaneko J, Tamura S, Aoki T, Sakamoto Y, et al. Once-daily tacrolimus in living donor liver transplant recipients. Biosci Trends. 2011;5(4):156–8.

Zhang Y, Chen X, Dai X, Leng X, Zhong D. Pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus converted from twice-daily formulation to once-daily formulation in Chinese stable liver transplant recipients. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32(11):1419–23. doi:10.1038/aps.2011.125.

Carcas-Sansuan A, Hierro L, Almeida-Paulo G, Frauca E, Tong H, Diaz C, et al. Conversion from Prograf to Advagraf in adolescents with stable liver transplants: comparative pharmacokinetics and 1-year follow-up. Liver Transplant. 2013;19(10):1151–8. doi:10.1002/lt.23711.

Mendez A, Berastegui C, Lopez-Meseguer M, Monforte V, Bravo C, Blanco A, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of conversion from tacrolimus twice-daily to tacrolimus once-daily in stable lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;97(3):358–62. doi:10.1097/01.TP.0000435699.69266.66.

Alloway R, Vanhaecke J, Yonan N, White M, Haddad H, Rabago G, et al. Pharmacokinetics in stable head transplant recipients after conversion from twice-daily to once-daily tacrolimus formulations. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30(9):1003–10. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2011.02.008.

Andrés A, Delgado-Arranz M, Morales E, Dipalma T, Polanco N, Gutierrez-Solis E, et al. Extended-release tacrolimus therapy in de novo kidney transplant recipients: single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(8):3034–7. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.07.044.

Bunnapradist S, Ciechanowski K, West-Thielke P, Mulgaonkar S, Rostaing L, Vasudev B, et al. Conversion from twice-daily tacrolimus to once-daily extended release tacrolimus (LCPT): the phase III randomized MELT trial. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(3):760–9. doi:10.1111/ajt.12035.

Crespo M, Mir M, Marin M, Hurtado S, Estadella C, Guri X, et al. De novo kidney transplant recipients need higher doses of Advagraf compared with Prograf to get therapeutic levels. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(6):2115–7. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.05.014.

Ishida K, Ito S, Tsuchiya T, Imanishi Y, Deguchi T. Clinical experience with once-daily tacrolimus in de novo kidney transplant recipients from living donors in Japan: 1-year follow up. Cent Eur J Urol. 2013;66(3):344–9. doi:10.5173/ceju.2013.03.art26.

Jelassi ML, Lefeuvre S, Karras A, Moulonguet L, Billaud EM. Therapeutic drug monitoring in de novo kidney transplant receiving the modified-release once-daily tacrolimus. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(2):491–4. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.01.043.

Kitada H, Okabe Y, Nishiki T, Miura Y, Kurihara K, Terasaka S, et al. One-year follow-up of treatment with once-daily tacrolimus in de novo renal transplant. Exp Clin Transplant. 2012;10(6):561–7. doi:10.6002/ect.2012.0087.

Silva HT, Yang HC, Abouljoud M, Kuo PC, Wisemandle K, Bhattacharya P, et al. One-year results with extended-release tacrolimus/MMF, tacrolimus/MMF and cyclosporine/MMF in de novo kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(3):595–608. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01661.x.

van Boekel GA, Aarnoutse RE, Hoogtanders KE, Havenith TR, Hilbrands LB. Delayed trough level measurement with the use of prolonged-release tacrolimus. Transpl Int. 2015;28(3):314–8. doi:10.1111/tri.12499.

European Medicines Agency. Questions and answers: positions on specific questions addressed to the Pharmacokinetics Working Party. London: European Medicines Agency, 2014 Contract No.: EMA/618604/2008 Rev.10.

Considine A, Tredger JM, Heneghan M, Agarwal K, Samyn M, Heaton ND, et al. Performance of modified-release tacrolimus after conversion in liver transplant patients indicates potentially favorable outcomes in selected cohorts. Liver Transpl. 2015;21(1):29–37. doi:10.1002/lt.24022.

Niioka T, Kagaya H, Miura M, Numakura K, Saito M, Inoue T, et al. Pharmaceutical and genetic determinants for interindividual differences of tacrolimus bioavailability in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Clinic Pharmacol. 2013;69(9):1659–65. doi:10.1007/s00228-013-1514-8.

Benkali K, Rostaing L, Premaud A, Woillard J, Saint-Marcoux F, Urien S, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and Bayesian estimation of tacrolimus exposure in renal transplant recipients on a new once-daily formulation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(10):683–92.

Woillard J, de Winter B, Kamar N, Marquet P, Rostaing L, Rousseau A. Population pharmacokinetic model and Bayesian estimator for two tacrolimus formulations—twice daily Prograf® and once daily Advagraf®. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(3):391–402. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03837.x.

Saint-Marcoux F, Debord J, Undre N, Rousseau A, Marquet P. Pharmacokinetic modeling and development of Bayesian estimators in kidney transplant patients receiving the tacrolimus once-daily formulation. Ther Drug Monit. 2010;32(2):129–35. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181cc70db.

Saint-Marcoux F, Debord J, Parant F, Labalette M, Kamar N, Rostaing L, et al. Development and evaluation of a simulation procedure to take into account various assays for the Bayesian dose adjustment of tacrolimus. Ther Drug Monit. 2011;33(2):171–7. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31820d6ef7.

Zhao W, Fakhoury M, Baudouin V, Storme T, Maisin A, Deschenes G, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of once daily prolonged-release formulation of tacrolimus in pediatric and adolescent kidney transplant recipients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(2):189–95. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1330-6.

Press R, Ploeger B, den Hartigh J, van der Straaten T, van Pelt J, Danhof M, et al. Explaining variability in tacrolimus pharmacokinetics to optimize early exposure in adult kidney transplant recipients. Ther Drug Monit. 2009;31(2):187–97.

Posadas Salas MA, Srinivas TR. Update on the clinical utility of once-daily tacrolimus in the management of transplantation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:1183–94. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S55458.

Adam R, Karam V, Delvart V, Trunecka P, Samuel D. Improved survival in liver transplant recipients receiving prolonged-release tacrolimus in the European Liver Transplant Registry. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(5):1267–82.

Trunecka P, Klempnauer J, Beckstein WO, Pirenne J, Friman S. Renal function in de novo liver transplant receipients receiving different prolonged-release tacrolimus regimens—the DIAMOND study. Am J Transplant. 2015. doi:10.1111/ajt.13182 (Epub 2015 Feb 23).

Tszyrsznic W, Borowiec A, Pawlowska E, Jazwiec R, Zochowska D, Bartlomiejczyk I, et al. Two rapid ultra performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC/MS/MS) methods with common sample pretreatment for therapeutic drug monitoring of immunosuppressants compared to immunoassay. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;928:9–15. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.03.014.

Hétu PO, Robitaille R, Vinet B. Successful and cost-efficient replacement of immunoassays by tandem mass spectrometry for the quantification of immunosuppressants in the clinical laboratory. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2012;883–884:95–101. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.10.034.

Hougardy J, de Jonge H, Kuypers D, Abramowicz D. The once-daily formulation of tacrolimus: a step forward in kidney transplantation? Transplantation. 2012;93(3):241–3. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e31823aa56e.

Wallemacq P, Armstrong VW, Brunet M, Haufroid V, Holt DW, Johnston A, et al. Opportunities to optimize tacrolimus therapy in solid organ transplantation: report of the European consensus conference. Ther Drug Monit. 2009;31(2):139–52. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e318198d092.

Min DI, Chen HY, Lee MK, Ashton K, Martin MF. Time-dependent disposition of tacrolimus and its effect on endothelin-1 in liver allograft recipients. Pharmacother. 1997;17(3):457–63.

Tsunashima D, Kawamura A, Murakami M, Sawamoto T, Undre N, Brown M, et al. Assessment of tacrolimus absorption from the human intestinal tract: open-label, randomized, 4-way crossover study. Clin Ther. 2014;36(5):748–59. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.02.021.

Thörn M, Finnström N, Lundgren S, Rane A, Lööf L. Cytochromes P450 and MDR1 mRNA expression along the human gastrointestinal tract. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60(1):54–60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02389.x.

Paine MF, Khalighi M, Fisher JM, Shen DD, Kunze KL, Marsh CL, et al. Characterization of interintestinal and intraintestinal variations in human CYP3A-dependent metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283(3):1552–62.

McKinnon RA, Burgess WM, Hall PM, Roberts-Thomson SJ, Gonzalez FJ, McManus ME. Characterisation of CYP3A gene subfamily expression in human gastrointestinal tissues. Gut. 1995;36(2):259–67.

Hesselink D, Bouamar R, Elens L, van Schaik R, van Gelder T. The role of pharmacogenetics in the disposition of and response to tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(2):123–39. doi:10.1007/s40262-013-0120-3.

Kramer B. Tacrolimus prolonged release in kidney transplantation. Exp Rev Clin Immunol. 2009;5(2):127–33. doi:10.1586/1744666X.5.2.127.

Trunečka P, Boillot O, Seehofer D, Pinna AD, Fischer L, Ericzon BG, et al. Once-daily prolonged-release tacrolimus (Advagraf) versus twice-daily tacrolimus (Prograf) in liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(10):2313–23. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03255.x.

Staatz C, Goodman L, Tett S. Effect of CYP3A and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of calcineurin inhibitors: part I. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(3):141–75.

Staatz C, Goodman L, Tett S. Effect of CYP3A and ABCB1 Single nucleotide polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of calcineurin inhibitors: part II. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(4):207–21.

Filler G, Vinks A, Huang S, Jevnikar A, Muirhead N. Similar MPA exposure on modified release and regular tacrolimus. Ther Drug Monit. 2014;36(3):353–7. doi:10.1097/FTD.0000000000000021.

Borra LCP, Roodnat JI, Kal JA, Mathot RAA, Weimar W, van Gelder T. High within-patient variability in the clearance of tacrolimus is a risk factor for poor long-term outcome after kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(8):2757–63. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq096.

Muduma G, Odeyemi I, Pollock RF. A UK analysis of the cost of switching renal transplant patients from an immediate-release to a prolonged-release formulation of tacrolimus based on differences in trough concentration variability. J Med Econ. 2014;17(7):520–6. doi:10.3111/13696998.2014.916713.

Pollock-Barziv SM, Finkelstein Y, Manlhiot C, Dipchand AI, Hebert D, Ng VL, et al. Variability in tacrolimus blood levels increases the risk of late rejection and graft loss after solid organ transplantation in older children. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14(8):968–75. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01409.x.

Crespo M, Mir M, Marin M, Hurtado S, Estadella C, Gurí X, et al. De novo kidney transplant recipients need higher doses of Advagraf compared with Prograf to get therapeutic levels. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(6):2115–7. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.05.014.

Hochleitner BW, Bösmüller C, Nehoda H, Frühwirt M, Simma B, Ellemunter H, et al. Increased tacrolimus levels during diarrhea. Transpl Int. 2001;14(4):230–3. doi:10.1007/s0014710140230.

Obi Y, Ichimaru N, Kato T, Kaimori J, Okumi M, Yazawa K, et al. A single daily dose enhances the adherence to immunosuppressive treatment in kidney transplant recipients: a cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17(2):310–5. doi:10.1007/s10157-012-0713-4.

Kuypers D, Peeters P, Sennesael J, Kianda M, Vrijens B, Kristanto P, et al. Improved adherence to tacrolimus once-daily formulation in renal recipients: a randomized controlled trial using electronic monitoring. Transplantation. 2013;95(2):333–40. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3182725532.

Muduma G, Odeyemi I, Smith-Palmer J, Pollock R. Budget impact of switching from an immediate-release to a prolonged-release formulation of tacrolimus in renal transplant recipients in the UK based on differences in adherence. Pat Pref Adher. 2014;8:391–9. doi:10.2147/PPA.S60213.

Gaudry K. Evergreening: a common practice to protect new drugs. Nature Biotechnol. 2011;29(10):876–9. doi:10.1038/nbt.1993.

First MR. First clinical experience with the new once-daily formulation of tacrolimus. Ther Drug Monit. 2008;30(2):159–66. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e318167909a.

Prograf and Advagraf mix-up. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(5):417–8.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

No funding was received for the preparation of this review.

Christine Staatz and Susan Tett have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Staatz, C.E., Tett, S.E. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Once-Daily Tacrolimus in Solid-Organ Transplant Patients. Clin Pharmacokinet 54, 993–1025 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-015-0282-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-015-0282-2