Abstract

Objective

Our objective was to assess the incidence and quality of reporting of published health economic evaluations in mainland China and compare the quality of peer-reviewed articles in Chinese and English.

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted for economic evaluations pertaining to China published from 2006 to 2015 using the PubMed, CBM, CMCC, CNKI, VIP, and Wanfang databases. All studies in English that met the inclusion criteria were included. For studies in Chinese, 200 sampled studies were included according to the random seeds method, and the same number of the most-cited studies in Chinese as those in English were included according to the number of citations and journal grades. Researchers independently assessed the quality of the studies using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist.

Results

After literature search and screening, a total of 310 studies were identified. The majority of these studies were cost-effectiveness studies (82.26%). Scores among different CHEERS items varied greatly. There was a gap between the average quality scores of the studies published in Chinese and those published in English (49.78 ± 9.31 vs. 82.48 ± 17.69) and between the average quality scores of the included most-cited studies in Chinese and English, which was slightly smaller (54.08 ± 10.27 vs. 82.48 ± 17.69). The methods, results, and discussion sections of studies published in Chinese were of low quality.

Conclusion

The quality of reporting of health economic evaluations in mainland China has developed slowly. Most of the included studies were incomplete in the presentation of content, making the results less reliable. It is important to standardize and improve the quality of Chinese health economic research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Although the average scores of the included most-cited studies in Chinese were higher than the sampled studies in Chinese, a large gap persisted between Chinese and English publications. |

The methods, results, and discussion sections of the studies published in Chinese were of low quality. |

Editors of Chinese journals need to consider adopting improved quality standards, evaluate submitted articles according to the more stringent requirements of the CHEERS criteria, and urge authors to provide higher-quality work for publication. |

1 Introduction

In China, resource allocation and cost issues must be considered in policy decisions about health-related population interventions [1]. Utilizing limited health resources to their best effect is one of China's medical and health industry reform and development goals. The problem of “difficult and expensive medical treatment” has not been effectively solved in China. The policy of “targeted poverty alleviation” in China also has higher requirements for allocating health resources. Health economic evaluation research could be important at this crucial time as it provides insights into managing healthcare costs and ensuring optimal use of scarce resources. Generally, health economic evaluations are now cited routinely to assess the quality of related literature in framing policy statements, consensus guidelines, and professional society technical reviews [2].

At present, the well-recognized guidelines for evaluating the quality of health economic evaluations can be divided into two categories. The first are guidelines that focus more on conduct, such as The Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) and The Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC). The second are guidelines that focus more on the reporting, such as the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS). The main purpose of this research was to evaluate the quality of reporting of health economic evaluations in mainland China and help Chinese researchers to understand the problems in their reporting, to report health economics evaluations in a more standardized way, and to better interpret the process and results of health economic evaluations. For these reasons, we chose CHEERS as the tool for this research. CHEERS [3] was published in 2013 and is an evaluation checklist of 24 items mainly used to guide the reporting of health economic evaluations and evaluate the quality of publications in peer review. The types of research evaluated can cover various subjects such as pharmacoeconomics, health intervention measures, vaccines, and medical equipment. CHEERS is well-recognized by most health economists as it reflects the quality of reporting of health economics evaluations satisfactorily.

In addition, we believed that the quality of studies differs between those in Chinese and those in English. As such, we conducted a comparative analysis to help researchers who have no experience in publishing English literature to write higher-quality reports and provide a standard for editors of Chinese journals to improve the quality of their publications.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature Search and Screening

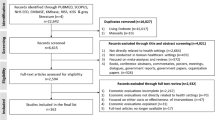

Figure 1 provides an overview of the identification of the included studies as a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram. A targeted literature review was designed using relevant search terms for health interventions in China and economic analyses. The search strategy was developed using medical subject headings related to health interventions and types of cost-analysis studies in China.

A systematic search of the literature was conducted using the PubMed databases (in English) and the CBM, CNKI, VIP, and Wanfang databases (in Chinese) to identify health economic evaluation studies pertaining to China in both Chinese and English from 2006 to 2015. Search terms included the keywords health economic, cost, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-minimization analysis, cost-utility analysis, cost-benefit analysis, economics evaluation, and China, either used alone or combined with a Boolean operator. The search strategy for the PubMed search engine is presented in Supplementary Material, Box 1.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) original studies reporting the findings of health economic evaluations in China; (2) studies were full economic evaluations comparing both costs and consequences and included a comparison of alternatives [1]; (3) studies were conducted in mainland China; (4) the first author was from China, except for Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan; and (5) the manuscript was published in English or Chinese. Studies comparing publications from multiple countries were excluded. Articles were excluded if they were only introductions to health economic evaluations in public health (with no data) or if costs were not a main topic of the study. However, the reference lists of these articles were screened to identify additional relevant articles. Full journal publication was required for a study to be included in this review; thus, meeting abstracts, letters to the editor, treatment guidelines or recommendations, expert opinions, and narrative reviews were excluded.

All studies in English that met the inclusion criteria were included. For the studies in Chinese, two types of studies were included. First, we used the random seed method to select 200 studies from the pool of 6345 studies that met the inclusion criteria. These 200 sampled studies represented the general quality of Chinese studies to a certain extent. Second, we selected the 57 most cited studies published in journals from Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index or the Core Journal of China from the pool. We considered these 57 most-cited studies to represent the quality of high-level Chinese studies.

All literature was screened by two independent reviewers (YZ and MT). Where these reviewers disagreed, four reviewers discussed the literature to reach a conclusion (SCZ, JHC, YZ, and MT). The primary reason for exclusion was recorded during the screening and review process.

2.2 Data Extraction and Evaluation of Studies

A bespoke data extraction table was used to collate extracted data, which mainly included general study characteristics (i.e., year of publication, type of health economic evaluation, type of intervention, affiliation of the first author, and funding source) and study details (i.e., costs, outcomes, valuation methods, discounting rate, and sensitivity analysis).

The CHEERS checklist comprises 24 items to assess the quality of reporting. Our reviewers used an English-language checklist to rate each report. The 24 items were scored using “yes” (reported in full), “part” (partially reported), “no” (not reported), and “NA” (not applicable). To estimate a reporting score, we assigned a score of 1 for complete reporting, 0.5 for partial reporting, and 0 for not reporting. Items marked as NA were not counted in the score. Equal weight was assigned to each item of the checklist. The scoring system can be shown as follows:

where NYes is the number of items marked “yes”, NPart is the number of items marked “part”, NNo is the number of items marked “no”, and NItem is the total number of items except for “NA.” The maximum possible score for an article that completely reported all information was 100.

2.3 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis, including frequency and percentages, was used to describe the characteristics of the included studies. The differences in characteristics between the Chinese and English studies were compared using the chi-squared test.

In addition to language, the scores of articles in different categories were compared according to the type of intervention, first-author affiliation, and funding. Different types of intervention mean that studies belong to different research fields and have different professionalism and writing logic requirements. Different research institutions have different research policies, organizational supervision, and research resources. Authors from universities, hospitals, or Centers for Disease Control (CDCs) also work in differing research fields. Although many articles are jointly completed by authors from different institutions, the contribution of the first author is relatively higher. The availability of research resources affects the quality of scientific research reporting; this can be seen in the conclusions of studies with and without funding. The differences in scores between these different categories were compared using the rank-sum test, and we used Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to test whether the factors were related. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.

3 Results

After screening, 310 studies were included in the review. Of these, 200 were sampled studies in Chinese [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203], 57 were the most-cited studies [6, 16, 33, 133, 264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315,316] in Chinese, and 57 were published in English [204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260]. There were four duplicates between the included sampled studies and the most-cited studies in Chinese. Figure 2 shows the number of included studies published in each year. The number of included most-cited studies in Chinese and studies in English increased significantly after 2012.

Figure 3 shows a comparison of the number and overall score trends between the included health economic evaluation studies in Chinese and English published between 2006 and 2015. The scores of both the included studies in English and the included most-cited studies in Chinese showed a steady growth trend, whereas the scores of the included studies in Chinese did not change significantly over time. The overall quality score of the included studies in English was always higher than that of the Chinese studies.

The study compared the characteristics of the included studies (Table 1). The most common type of analysis was cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA; 82.26%). Regarding the choice of outcome measures, most of the studies in Chinese chose clinical endpoints (sampled studies 96.50%, most-cited studies 70.18%) to measure health outcomes. Nearly half of the sampled studies in English chose quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) (42.11%) as health outcome measurements, followed by index clinical endpoints (38.60%). The time horizon of the included studies in Chinese was most commonly ≤ 1 year (sampled studies 85.50%, most-cited studies 61.40%). Nearly half of the included studies in English also had time horizons of ≤ 1 year (43.86%). The chi-squared test showed that the differences in time horizons of the included studies were statistically significant (χ2 = 92.82 [df = 6, N = 314], p < 0.001), and pairwise comparisons between these three study groups also showed statistically significant differences.

Overall, in terms of types of interventions, the included studies mostly focused on pharmaceuticals (48.64%). However, although most of the included sampled studies in Chinese focused on pharmaceuticals as the intervention (60.50%), most English studies focused on clinical treatments (64.91%) such as surgery and choice of clinical treatment plan. The rank-sum test showed that scores of studies focusing on clinical treatment were higher than those focusing on pharmaceuticals (mean rank 170.56 vs. 136.44, p = 0.010).

In terms of funding, if the article made no mention of funding, we assumed it was not funded. Most included studies in Chinese were not funded (sampled studies 93.50%, most-cited studies 52.63%), whereas only 19.30% of studies in English were not funded (χ2 = 136.79 [df = 2, N = 314], p < 0.001), and pairwise comparison between these three study groups also showed statistically significant differences. The rank-sum test showed that studies with funding scored higher than those without funding (mean rank 207.91 vs. 126.67, p < 0.001). According to the affiliations of each study’s first author, most came from the hospital sector. The first author of the Chinese studies were mostly affiliated with hospitals (sampled studies 92.50%; most-cited studies 68.42%); however, few first authors of English studies were affiliated with hospitals (33.33%, χ2 = 100.56 [df = 4, N = 314], p < 0.001). The rank-sum test showed that studies with the first author from a university scored significantly higher than those with a first author from a hospital (mean rank 218.47 vs. 138.03, p < 0.001). There was a correlation between the first-author affiliation and funding (p < 0.001) and between first-author affiliation and intervention type (p < 0.001).

Table 2 presents an assessment of the quality of the included studies. The average quality score of the included studies was 56.59 ± 16.90. Scores varied greatly among the different CHEERS items. Most of the included studies were of good quality in terms of title (95.32), choice of health outcomes (90.32), model-based estimating resources and costs (83.33), and setting and location (83.50). However, the included studies rated poorly on some items, especially those about the choice of model (18.02), assumptions (18.77), and discount rate (17.90).

There was a distinct gap between the average quality scores of the included sampled studies in Chinese (49.78 ± 9.31) and those in English (82.48 ± 17.69). Similarly, a gap existed between the average quality scores of the included most-cited studies in Chinese (54.08 ± 10.27) and those in English, which was slightly narrower. The average quality score of the included studies in Chinese was lower than that of the English studies for most items. The average quality scores of the included sampled studies in Chinese were only higher than those in English for the following items: title (98.75 vs. 91.23), synthesis-based measurement of effectiveness (83.33 vs. 66.67), and estimating resources and costs (single study-based 61.86 vs. 41.46 and model-based 90.00 vs. 84.78). The included most-cited studies in Chinese did not have synthesis-based estimates. The average quality scores of the included most-cited studies in Chinese were only higher than those in English for the item estimating resources and costs (single study-based 81.52 vs. 41.46).

Figures 4, 5 and 6 show the comparison of the proportion of the included studies in Chinese and English scored as completely adequate, partially, or not at all based on CHEERS items. The most frequent partially or not reported items were “conflicts of interest.” Most of the included sampled studies (0.75) and most-cited studies (1.75) in Chinese did not describe any potential conflicts of interest of study contributors, whereas almost three-quarters of the included studies in English (87.72) did. The discount rate was stated in 5% of the included sampled studies in Chinese, 19.30% of the included most-cited studies in Chinese, and 66.67% of those in English. Although it is common practice to not apply discount rates for economic evaluations with short time horizons (e.g., < 1 year), researchers are encouraged to report this rate as 0% for clarity [261]. Additionally, fewer included sampled studies (5%) and most-cited studies (22.81%) in Chinese used model-based estimating than did studies in English (80.70%). The average quality scores in terms of model-based characterizing heterogeneity were much lower for the included sampled studies (55.00) and most-cited studies (69.32) in Chinese than for those in English (73.08). In addition, when describing the relevant content of the decision-analytic model, the scores of the included sampled and most-cited studies in Chinese were much lower than those in English.

4 Discussion

The quality of reporting of health economic evaluations in mainland China has developed slowly. Although the average scores of the included most-cited studies in Chinese were higher than those of the sampled studies in Chinese, both scores consistently differed widely from those of the included English studies.

The overall quality score of the included studies in Chinese was low. Many of the included studies in Chinese provided only a simple description of the cost and outcome indicators and did not fully describe the design features of the single effectiveness study or the reasons why the single study was a sufficient source of clinical-effectiveness data. As the time horizon of clinical events and healthcare interventions and their consequences are important aspects of health economic evaluations [262], they all affect estimated costs and results [263]. The choice of time horizon and the methods for adjusting estimated unit costs can be challenging for many analysts and policy makers, many of whom may not have strong familiarity with economic concepts. Researchers have different backgrounds and clinical experience and therefore different understanding and ability to apply health economic and model methods. In addition, most of the included studies in Chinese only summarized their key findings in the discussion but did not describe the limitations of the study. As a result, most of the included studies in Chinese scored poorly for the quality of methods, results, and discussions.

The quality of reporting of the included studies was associated with the first-author’s affiliation and the intervention type. The first-author’s affiliation was also related to intervention type. This may be because researchers from hospitals have good knowledge of and experience in clinical medicine and pharmacy and researchers from universities have relatively solid theoretical knowledge. Those working in CDCs and other institutions also have theoretical knowledge and practical experience in epidemiology and public health. Health economic evaluations involve the application of multiple disciplines in the field of health and are closely related to medicine, hygiene, demography, and sociology. Increasing cooperation between personnel in various professional fields as well as multidisciplinary communication would help improve the quality of health economic evaluation research.

Whether the source of funding was indicated was significantly related to the quality of reporting. Health economic research is resource consuming and requires a certain amount of human, financial, and material resources. Financial guarantees could enable research to proceed smoothly. A lower proportion of Chinese studies indicated funding status, which may also be the reason for the lower quality score.

The differences in scores between the included studies in Chinese and English also reflected that editors of Chinese journals need to consider adopting improved quality standards. The CHEERS guidelines have good operability and are freely available for editors and peer reviewers. The quality of studies in Chinese would be improved if editors of and peer reviewers for Chinese journals were familiar with the CHEERS checklist items, evaluated according to the higher requirements of the CHEERS guidelines, and urged authors to complete their studies to a higher quality.

4.1 Study Limitations

This review has some limitations. CHEERS is a qualitative instrument used to measure the quality of reporting rather than a quantitative instrument. We tried a quantitative approach based on CHEERS but it may have potential bias.

The period of the search was from 2006 to 2015. We acknowledge that the quality of health economic evaluations in mainland China may have improved between 2016 and 2021.The year 2015 is the final year of China's Twelfth Five-Year Plan and 2016 is the first year of the Thirteenth Five-Year Plan. The year 2016 was also when medical and health industry reforms began to deepen. In 2016, China carried out inspections and reforms on medical insurance payments, drug prices, and medical service provision. According to the reform plan, China would establish a basic medical and health system covering urban and rural residents by 2020. These events would certainly have had an impact on the quality of reporting of health economic evaluations in mainland China. However, we believe that the gap in the quality of reporting between Chinese and English studies, as well as some other common problems, would still exist after 2015. Therefore, our project is mainly divided into two stages. The first stage was to assess the quality of studies published from 2006 to 2015, which reflects the past situation. We mainly focus on horizontal comparison in this first stage. The second stage will be to assess the quality of studies published from 2016 to 2020, which will reflect the current situation. In this stage, we will mainly focus on the analysis of longitudinal time series.

The number of studies in Chinese that met the inclusion criteria was too large to review each study individually; therefore, the case-matching principle of epidemiological case–control studies was used for reference. That is, the matching ratio can be 1:1 or 1:2 but should not be greater than 1:4. The number of English studies that met the criteria was 57, so we chose 200 as the matching number of Chinese studies. Using the random seed method for sampling, the probability of each study being selected was equal. Therefore, we assumed that the 200 selected studies satisfactorily represented the quality of 6345 studies. We also acknowledge that the result may have been different had the sample size been larger.

5 Conclusions

The number of health economics evaluation studies in China increased steadily over the 10 years from 2006 to 2015. However, many problems with the research designs, presentation of results, and related explanations persisted. Most of the research content was incompletely presented, decreasing the reliability of the results. Therefore, standardizing and improving health economics research is of great significance for China.

References

Batura N, Pulkki-Brannstrom AM, Agrawal P, Bagra A, Haghparast-Bidgoli H, Bozzani F, et al. Collecting and analysing cost data for complex public health trials: reflections on practice. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23257. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23257.

Spiegel BMR, Targownik LE, Kanwal F, Derosa V, Dulai GS, Gralnek IM, et al. The quality of published health economic analyses in digestive diseases: a systematic review and quantitative appraisal. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(2):403–11.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)-explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR health economic evaluation publication guidelines good reporting practices task force. Value Health. 2013;16(2):e1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.010.

Bao DY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three kinds of proton pump inhibitors to eradicate Helicobacter pylori in treating peptic ulcer. Strait Pharm. 2012;24(10):249–51.

Cai JW, Ji LY, Liu XH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three drugs in the treatment of schizophrenia. Strait Pharm. 2008;06:123–5.

Cai YM, Zhang HM, Zhou H, Hong FC, Cheng JQ, Zhang YJ, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of the project to prevent and control mother-to-child transmission of syphilis. Chin Public Health. 2007;09:1062–3.

Lj CAO. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness analysis of two drugs in the treatment of mild to moderate hypertension. Chin Med Guide. 2012;10(35):255–6.

Cao LZ, Liu RS, Ran LL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different chemotherapy regimens for 147 patients with lung cancer. Med Herald. 2006;08:842–3.

Chen B, Li G. Cost-effectiveness analysis of omeprazole and pantoprazole sodium in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori positive peptic ulcer. China Pharm. 2011;20(07):40–1.

Chen CY, Wu QH, Xiao XZ, Ma LY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two methods for treating urinary tract infection. China Med Herald. 2008;21:49–50.

Chen HW. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three drug regimens to eradicate Helicobacter pylori. J Pract Med Technol. 2007;14:1817–8.

Chen JX, Wang D, Li GF, Gao EM, Wang H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two schemes in the treatment of hypertension complicated with hyperlipidemia. Med Forum Mag. 2006;12:102–3.

Chen M, Zhong SM, Li Z. The effect and cost-effectiveness analysis of compound lidocaine cream in erythropoietin injection. Clin J Pract Hosp. 2013;10(05):142–5.

Chen QZ, Cao C, Lin SN. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different hypertension management models. J Chronic Dis. 2015;16(02):163–6.

Chen XF, Xiang ZG, Li KJ, Yang SL, Zheng Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of levofloxacin and clarithromycin in the treatment of peptic ulcer with Helicobacter pylori infection. China Pharm. 2013;22(18):84–6.

Chen XJ, Xia ZH, Chen MZ, Huo JG. Cost-effectiveness study of four chemotherapeutics bladder perfusion to prevent superficial bladder cancer recurrence after transurethral bladder tumor resection. Chin Gen Pract. 2012;15(19):2188–90.

Chen Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three treatments for children with acute viral myocarditis. China Med Frontier. 2012;7(08):70–82.

Chen Z, Chen YQ, Liu H. Cost-benefit analysis of benazepril and captopril in the treatment of chronic congestive heart failure. Jiangsu Med. 2006;04:377–8.

Chen ZG, Dou WQ, Wu DL, Zhang Y, Xu X, Gu QJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of domestic and imported somatostatin in the treatment of acute pancreatitis. China Med Herald. 2012;9(33):123–4.

Cheng T, Zheng JB. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three kinds of drugs in treatment of female acute cystitis. Int Med Health Guid News. 2008;21:84–5.

Dang QF. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three drug regimens in eradicating Helicobacter pylori. Northwest Pharm J. 2009;24(05):405–6.

Deng HY, Pan WJ, Li B, Huang AJ. Analysis of the cost and effect of three treatments for bronchopneumonia in children. Hebei Med. 2009;15(03):310–2.

Deng JH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ligustrazine and ginkgo biloba in the treatment of coronary heart disease and angina pectoris. Med Rev. 2012;18(21):3689–90.

Ding XY, Zhang GY, Feng Q, Li RH, Zhi LJ. Pharmacoeconomics research on antibacterial drugs in treating children’s septic arthritis. China Pharm. 2014;23(21):59–60.

Du SZ, Kan QC. Cost analysis and effect study of three statins in the treatment of hyperlipidemia. Medical Forum Mag. 2010;31(23):25-6+8.

Du SZ, Zhang XJ, Yue XH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens for breast cancer. Chin Pharm. 2011;22(12):1109–10.

Du YL, Wang Z. Cost-effectiveness analysis of intensive treatment of inpatients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes in Xinjiang. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ (Medical Edition). 2015;35(03):437–40.

Du YM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of felodipine combined with losartan or hyzaar to lower blood pressure. Drug Appl Monit China. 2007;02:33–5.

Du YM. Economic analysis of three schemes for treatment of peptic ulcer. Chin New Clin Med. 2009;2(06):614–6.

Duan XM, Wang TR, Chen F, Xiang B, Kong FM. Study on the efficacy and cost of combined blood purification in the treatment of severe organophosphorus pesticide poisoning. Southwest Natl Def Med. 2014;24(10):1060–2.

Fang YH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cephalosporin sequential treatment of bacterial lower respiratory tract infection. J Qiqihar Med Coll. 2008;11:1318–9.

Feng LN, Wu ZC, He P, Jiao L, Su XG. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of three chemotherapy regimens for advanced esophageal cancer. Chin J Hosp Pharm. 2015;35(15):1409–12.

Feng WY, Feng B. Analysis of the economic effects of three clinical medication regimens in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Chongqing Med. 2011;40(09):888–90.

Fu M, Gu YX, Song DL, Leng B, Wang QH, Ying XH. Comparison of the effects and costs of intravascular embolization and surgical clipping for the treatment of ruptured communicating artery aneurysms before or after. Int J Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;04:269–74.

Gan XH, Feng W, Wang Y, Li SZ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for high-risk ovarian cancer patients. Zhongnan Pharm. 2013;11(09):714–7.

Gao ST. Pharmacoeconomics study on the treatment of condyloma acuminatum with 4 topical drugs, including imiquimod and podophyllotoxin. Strait Pharm. 2014;26(07):177–9.

Gao SG. Effect of domestic pantoprazole and imported omeprazole in the treatment of peptic ulcer bleeding-cost analysis. Liaoning Med J. 2013;27(02):91–2.

Geng GM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three combined medication regimens in the treatment of acute cerebral infarction. Chin Pharm. 2012;15(10):1477–9.

Gong JM, Wang CM, Hu SJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of four drug treatments for schizophrenia. China Pract Med. 2008;27:66–8.

Guo H, Li YY, Sun Y, Li WJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of four chemotherapy regimens after invasive breast cancer surgery. Chin Pharm. 2007;11:810–2.

Han XQ, Mi XJ, Wei X, Han YQ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two alternative azithromycin and erythromycin regimens in the treatment of mycoplasma pneumonia in children. Shandong Med. 2007;35:41–2.

He CS, Zhou SC. Cost-effectiveness analysis of saxagliptin on type 2 diabetes with secondary failure of metformin. China Pharm. 2015;24(14):104–5.

He W, Liu H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three schemes for the treatment of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. J Armed Police Logist Coll (Medical Edition). 2012;21(03):182–3.

He Y, Yu XB. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three drugs in the treatment of genital chlamydia infection. China Pharm. 2011;20(01):58–9.

Hu CH, Li C, Xu H. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of two treatment options for acute pancreatitis. Zhejiang Clin Med J. 2015;8:1372–3.

Hu LR, Fan F, Zhao T, Ding XM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of domestic and imported letrozole. Jiangxi Med. 2011;46(04):362–4.

Hu YH, Zhu WZ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of Jilifen and Huierxue in treating malignant tumors with leukopenia after chemotherapy. China Pharm. 2010;19(21):39–40.

Hu ZT, Liang YQ. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of 4 treatment options for essential hypertension. Chin Community Physician (medical major). 2011;20(13):10–1.

Huang C, Zhu LQ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three schemes for the treatment of bronchopneumonia in children. Strait Pharm. 2008;03:121–2.

Huang JB, Ye YH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of rabeprazole, omeprazole and pantoprazole in the treatment of peptic ulcer. Guangxi Med. 2014;36(09):1328–9.

Huang XY, Deng LL, Zhang MA, Deng M, Su XM. Analysis of cost and effect of guiling powder combination in treating irregular menstruation. Chin Med Innov. 2015;12(19):82–4.

Ji B, Liu S. Cost-effectiveness analysis of oral hypoglycemic drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Ration Use. 2009;2(16):27–8.

Jiang Y, Zhou LF. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three drugs in the treatment of bronchial pneumonia in children. Chin Pharm. 2007;11:812–3.

Jiao HL, Zhang BS. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three schemes for treating lower respiratory tract infection. J Ningxia Med Univ. 2011;33(11):1091–3.

Jiao WJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three drug treatments for pneumoconiosis patients with intrapulmonary infection. Prev Med Forum. 2008;14(12):1093–4.

Jin Y, Wan JH. Cost-effectiveness of cefuroxime and ofloxacin in the treatment of lower urinary tract infections. Contemp Med. 2015;21(01):132–3.

Kang Q, Xu DN, Yu Z. Cost-effectiveness analysis of EGFR-TKIs in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. China Drug Eval. 2013;30(06):377–80.

Kuang SH, Chen YQ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of loratadine combined with doxepin in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Chin School Doctor. 2014;28(07):513–5.

Lai HJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 4 kinds of antibacterial drugs for patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Anti Infect Pharm. 2015;12(01):93-5+116.

Lao GQ, Wang JL, Tang ZH. Cost-effectiveness comparison of 4 kinds of prazole drugs in the treatment of peptic ulcer. Med Herald. 2006;02:160–2.

Lei BJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of domestic and imported micronized fenofibrate in the treatment of hyperlipidemia. Intern Med. 2013;8(06):632–3.

Li HZ, Wang X, He M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 4 treatment options for community-acquired pneumonia. J Jiujiang Univ (Natural Science Edition). 2013;28(01):83–7.

Li J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of Xuesaitong injection and Shuxuening injection for angina pectoris. Chongqing Med. 2011;40(17):1747–8.

Li J, Zhu XF, Jin P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of domestic and imported amlodipine in the treatment of essential hypertension. Strait Pharm. 2011;23(11):219–20.

Li L. Cost-effectiveness analysis and clinical significance of treatment programs for grade 1 and 2 hypertension. Contemp Med. 2011;17(29):64–5.

Li SL, Wang PQ, Peng T, Xiao KY, Su M, Shang LM, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of arterial chemoembolization for preventing tumor recurrence after radical resection of liver cancer. Can Res. 2015;42(04):350–5.

Li X. Cost-effectiveness analysis of piperacillin/tazobactam and cefoperazone/sulbactam in the treatment of respiratory tract bacterial infections. Chin Pharm. 2006;05:353–4.

Li XJ, Bi XY, Jiang Y. Observation of curative effect and cost-effect analysis of two kinds of traditional Chinese medicine injection in treating acute upper respiratory tract infection in children. China Pharm. 2011;20(01):64–5.

Li XP, Zhao Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three triple therapies to eradicate Helicobacter pylori. Strait Pharm. 2011;23(06):260–1.

Li XX, Xiong W, Zhang QX. Cost-effectiveness analysis of preventive use of antibacterial drugs during perioperative period of cesarean section. Strait Pharm. 2013;25(10):166–8.

Li YP, Guan L. Cost-effectiveness analysis of imported and domestic glimepiride tablets in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Pract Diabetes. 2009;5(06):48–9.

Li YP, Guo LY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of insulin aspart 30 and oral hypoglycemic drugs in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Chin Pharm. 2010;13(03):413–4.

Liang XL, Ye JK. Cost-effectiveness analysis of tropisetron and palonosetron in preventing gastrointestinal reactions of chemotherapy. Chin Med Innov. 2014;11(02):116–8.

Liang YF, Kong LR, Deng XM. Efficacy of gatifloxacin and levofloxacin in the treatment of urinary system infections-cost analysis. Guangzhou Med. 2007;05:62–4.

Liang YH, Xiao Y. Pharmacoeconomics study of three neurodermatitis treatment options. Eval Anal Drug Use Chin Hosp. 2015;15(07):895–7.

Liang YZ, Zhou XG. Cost-effectiveness analysis of Shenqi Wuweizi Tablets in treating insomnia with deficiency of both heart and spleen. Clin J Chin Med. 2009;21(05):413–5.

Liao GJ, Tan X, Sun XH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three treatment options for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Strait Pharm. 2006;05:173–4.

Liao XL, Lin YD, Qian YH, Dong MH, Gu J, Shi P. Effect and cost-benefit analysis of neonatal hepatitis B vaccination in Wuxi City. China Public Health Manag. 2008;05:534–6.

Lin DD, Zeng XJ, Chen HG, Hong XL, Tao B, Li XF, et al. Cost-effectiveness/benefit analysis of comprehensive management strategy for schistosomiasis in Poyang Lake area, focusing on infection source control. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 2009;27(04):297–302.

Lin GY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of desloratadine and epinastine in the treatment of chronic urticaria. China Contemp Med. 2013;20(13):149–50.

Lin P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 6 programs in the treatment of bronchial pneumonia in children. Strait Pharm. 2015;27(08):232–3.

Lin SY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two treatment options for angina pectoris of coronary heart disease. China Pract Med. 2010;5(34):126–8.

Lin Z, Liang XA. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of sequential treatment of amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium in children with acute lower respiratory tract infection. Western Med. 2011;23 (09):1795-6.

Liu B, Zeng XX. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Chin Med J Peking. 2013;11:841–4.

Liu HB, Li XQ, Hou LF. Safety of aripiprazole and olanzapine in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia with glucose and lipid metabolism and drug cost-effectiveness analysis. Mod J Integr Tradit Chin Western Med. 2015;24(27):2999–3001.

Liu J, Ling L, Zhao LL, Lin P, He Q. Evaluation and decision analysis of methadone maintenance treatment in community in Guangdong Province. China Health Stat. 2007;05:501–4.

Liu JB. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three medication regimens in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Chin Pharm. 2010;21(08):758–9.

Liu JB. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fleroxacin sequential therapy for urinary system infection. Chin J New Drugs Clin Med. 2010;29(06):466–8.

Liu XC. Clinical observation and cost-effectiveness analysis of Xinmaitong capsules for essential hypertension. China Med Guide. 2015;17(12):1222–4.

Liu Y, Deng JY, Li FZ, Huang H, Chen KH, Yuan P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of “chondroitin sulfate” and “celecoxib” in the treatment of adults with Kashin-Beck disease. Chin J Endemic Dis Control. 2009;24(01):38–40.

Liu YH, Zhang FY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of moxifloxacin sequential treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Chin J Misdiagn. 2009;9(21):5073–4.

Lu C. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three antibacterial therapies for children with acute respiratory bacterial infections. Asia Pac Tradit Med. 2009;5(12):129–30.

Lu HM, Zhu SQ, Du FQ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three chemotherapy regimens for non-small cell lung cancer. Strait Pharm. 2009;21(07):180–1.

Lu YG, Ji RX. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two schemes for treating peptic ulcer. China Pract Med. 2011;6(22):17–9.

Luo XJ, Zhu HH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of Xiyanping and Yanhuning in the treatment of viral pneumonia. China Pharm. 2012;21(16):68–9.

Luo XZ, Mo XX. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cefprozil and cefaclor in the treatment of upper respiratory tract infections in children. Chin Pharm Econ. 2014;9(07):9–10.

Luo YL, Cen JJ. The efficacy and economic analysis of domestic and imported irbesartan tablets in the treatment of essential hypertension. Asia Pac Tradit Med. 2012;8(06):180–1.

Luo YL, Zhang MY, Wu WY, Li CB, Yao J, Li QW. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fluoxetine in the treatment of persistent somatic pain disorder. Chin J Psychiatry. 2009;02:71–4.

Ma AX, Li HC, Jin XJ, Zhang XK, Chu YB, Fu YN. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of alfacalcidol and calcitriol in preventing osteoporotic fractures. Chin Med Guide. 2011;9(32):371–7.

Ma YY, Ha N. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two regimens of Chinese and Western medicines in the treatment of chronic heart failure. Chin Pharm. 2011;22(34):3174–6.

Mi YQ, Huang JD. Cost-effectiveness analysis of omeprazole and esomeprazole in the treatment of peptic ulcer. China Pharm. 2010;19(19):51–2.

Pan LZ, Cai RL, Chen YL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two treatment options for irritable bowel syndrome. Strait Pharm. 2010;22(10):207–9.

Pan MY. Efficacy evaluation and pharmacoeconomic analysis of opioid receptor antagonists in the treatment of severe head injury. Strait Pharm. 2013;25(06):272–4.

Pan QC, Lu QY, Yang J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three penicillin antibiotics in the treatment of pediatric bronchopneumonia. Chin Licens Pharm. 2015;12(10):23–6.

Pan YS, Peng XX. Post-marketing pharmacoeconomic evaluation of Bei Fuji in treating second degree burn. Chin Licens Pharm. 2010;7(03):28–32.

Pang JL, Meng GY, Zhang P, Liang H, Wei FH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of insulin detemir and insulin glargine in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Guangxi Med. 2013;35(10):1329-31+50.

Peng S, Chang D, Wang DC, Zhang WY. Hygienic economic evaluation of diarrhea-type irritable bowel syndrome in Guangdong with the method of suppressing the liver and strengthening the spleen. Hunan J Tradit Chin Med. 2015;31(02):11–3.

Qin B. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different treatments for acute cerebral infarction. Chin Folk Med. 2013;22(11):70–2.

Qin PP, Peng LH, Ren L, Min S. Cost comparison between continuous femoral nerve block and patient-controlled intravenous analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Anesthesiol. 2015;31(08):733–6.

Rao YH, Hu H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two programs for treatment of human papillomavirus infection in female reproductive tract. Eval Anal Drug Use Chin Hosp. 2008;05:372–4.

Shen HL, Zhou J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three kinds of Chinese patent medicine treatment schemes for breast hyperplasia. Chin Pharm. 2010;21(40):3818–9.

Shen JK, Wang ZF, Li ZQ. Cost-effective analysis of granulocyte colony stimulating factor in chemotherapy of acute myeloid leukemia in remission. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;04:289–90.

Shi H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two treatments for hypertension. China Contemp Med. 2012;19(02):157–8.

Shi YZ, An HL, Cheng M, Li JL. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of two kinds of ceftazidime in the treatment of lower respiratory infections. Pharm Clin Res. 2014;22(04):371–3.

Song YL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fluoroquinolones commonly used in clinical treatment of lower respiratory tract infections. Eval Anal Drug Use Chin Hosp. 2015;15(06):742–4.

Sun HJ, Sun Y, Chen BQ, Li YH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the preventive application of antibiotics in orthopedic aseptic surgery. J Pharmacoepidemiol. 2007;02:111–2.

Tan JH, Wang HH, Liu LP, Xie J, Hu LL. Health economics evaluation of seldinger PICC catheterization technology under ultrasound guidance. Chin J Mod Nurs. 2012;33:4008–10.

Tan JR, Li H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three treatment options for respiratory infections. Pharm Today. 2008;18(3):87–8.

Tao LP. Cost-benefit analysis of diammonium glycyrrhizinate and compound monoammonium glycyrrhizinate S and sodium chloride in the treatment of drug-induced liver damage. Strait Pharm. 2012;24(10):251–3.

Tao LP, Li X, Chen L, Wu CC, Hu B, Wang CH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and open surgery for choledocholithiasis and benign gallbladder lesions. West China Med. 2014;29(10):1823–6.

Tian W, Xu LZ. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness analysis of omeprazole and lansoprazole in preventing stress ulcer in critically ill patients. Eval Anal Drug Use Chin Hosp. 2014;14(06):506–7.

Wang CG, Xu YG, Wang P, Ren HX, Gao XK, Wei XQ, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of skin and soft tissue infections of vancomycin and linezole using decision tree model. Chin J Hosp Pharm. 2015;35(14):1298–302.

Wang DZ, Liu B, Zhang SY, Li DA, Yang XL. Economic analysis of Bootstrap method on the short-term efficacy of cisplatin-based chemotherapy for advanced esophageal cancer. J Pharmacoepidemiol. 2013;22(02):74–7.

Wang GL, Jing Y, Qiu P, Xu LF, Gong M, Wen P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 4 kinds of drugs in the treatment of severe head injury combined with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Mod J Integr Tradit Chin Western Med. 2011;20(33):4214–5.

Wang GL, Wen JB, Peng L, Wen P, Qiu P, Wang X, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of LAM, LdT, ETV combined with ADV in the treatment of ADV-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Shandong Med. 2013;53(16):39–41.

Wang HC, Xu YY, Zhang XC, Wang CL, Cao JW, He QJ. Efficacy and economic evaluation of Chinese medicine and immunomodulator in adjuvant treatment of retreatment of tuberculosis. Chin Gen Pract. 2014;17(06):706–9.

Wang HX. Cost-effectiveness analysis of five commonly used drugs in the treatment of acute cerebral infarction. Mod Chin Med Appl. 2014;8(04):147–8.

Wang K, Zhang W. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two treatments for ventricular premature contraction. China Pharm. 2008;07:41.

Wang LH, Hu JH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two dosage forms of paclitaxel combined with carboplatin in the first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer. Chin Pharm. 2012;23(24):2268–70.

Wang P, Wang DR, Wan H, Zhu XD, Liu J. Effectiveness and economic evaluation of different Chinese patent medicine injections in adjuvant treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Eval Anal Drug Use Chin Hosp. 2013;13(05):391–5.

Wang Q, Wang GL, Yi F, Qiu P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pantoprazole and omeprazole in preventing cerebral hemorrhage complicated with stress gastrointestinal bleeding. Mod J Integr Tradit Chin Western Med. 2010;19(21):2608–9.

Wang RS, Wei B, Su L, Feng QM, Zeng D, Luo HY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two radiotherapy options for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat. 2011;18(09):707–9.

Wang TL, Huang GZ. Efficacy of L-amlodipine besylate in antihypertensive and pharmacoeconomic evaluation. Chin J Gerontol. 2014;34(22):6299–301.

Wang WH, Lai XH, Wang HQ. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of fleroxacin sequential therapy for urinary system infection. Shenzhen J Integr Tradit Chin Western Med. 2015;25(15):189–90.

Wang WL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 2 kinds of antiviral drugs in the treatment of herpes zoster. Chin Pharm. 2007;08:564–5.

Wang XD. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of sirolimus used in liver transplant recipients. Chin J Emerg Resusc Disaster Med. 2008;3(12):731–3.

Wang XQ, Zhao LH, Zuo H, Song GZ, Xiong NY, Li FX. Cost-effectiveness analysis of azithromycin and three traditional Chinese medicines in the treatment of children with bronchopneumonia. Chin Prim Med. 2010;03:396–7.

Wang XX, Wang SY, Gan ZF, Zhou YZ, Chen QS. Effect and cost analysis of sequential treatment of azithromycin in children with lower respiratory tract infection. Chin Rural Med. 2013;20(05):7–8.

Wang XY, Zhu SZ, Wang ZY, Wu WY, Wu YY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of Danshen cream/ultrasound and Xiubi/ultrasound for preventing hypertrophic scar. Chin Med Sci. 2013;3(19):170–2.

Wang Y, Sheng MY, Tang ZQ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eval Anal Drug Use Chin Hosp. 2007;01:52–4.

Wang YC, Sun HG, Yang B, Liu G. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fluvoxamine and clomipramine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Chin Disabil Med. 2010;18(05):35–7.

Wang ZL, Li XE. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three sulfonylureas for initial treatment of type 2 diabetes. Chin Pharm. 2014;25(22):2019–21.

Wei CH, Wang SC, Yang Y, Ai J, Li RL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of traditional Chinese and western medicine treatment schemes for children with respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia with phlegm-heat obstructed lung. Jiangsu Tradit Chin Med. 2008;40(12):28–30.

Wei WX, Yuan JF, Chen JN, Zhou M, Wang T. Cost and effect analysis of niclosamide suspension on snail control in hilly areas. Shanghai J Prev Med. 2006;10:491–3.

Wu AR, Wang XQ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three antibacterial drugs in the treatment of non-gonococcal cervicitis. Mod Chin Med Appl. 2014;8(18):14–5.

Wu HW, Chen SQ, Xiao P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three traditional Chinese medicines for treating breast lobular hyperplasia. Guangxi Med. 2009;31(04):521–2.

Wu J, Zhang J. Cost-effectiveness comparison of Xuesaitong and Shuxuetong injection in the treatment of acute cerebral infarction. Chin Pharm. 2011;22(11):1037–8.

Wu JW, Zhang YF. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two antibacterial drugs in the treatment of urinary system infections. Chongqing Med. 2013;42(12):1395–7.

Wu PQ, Jing L, Li XM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two chemotherapy regimens for newly treated multiple myeloma. Chin Pharm. 2015;26(23):3169–72.

Wu QH, Wu JY, Chen CY, Yang JM, Ma LY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of joint venture and imported ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe urinary tract infections. China Med Herald. 2007;12:70–1.

Xia HL, Liu HG. Cost-effectiveness comparison of 5 kinds of Chinese patent medicines for treating chronic pharyngitis caused by exogenous wind-heat. Chin Rural Med. 2014;21(05):27–8.

Xia YF, Yan S. Cost-effectiveness analysis of domestic and imported clopidogrel in the treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Chin Pharm. 2012;23(40):3801–3.

Xiao J. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of two proton pump inhibitors in the treatment of active gastric ulcer infected by Helicobacter pylori. Hebei Med. 2014;20(03):413–5.

Xie BS. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 6 antibacterial drugs in the treatment of bacterial pneumonia. Chin Pharm. 2008;05:570–2.

Xie F, Li F. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three oral hepatoprotective drugs in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. China Pharm. 2013;22(20):91–2.

Xie MM, Zhuang J, Sun H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two combined blood pressure reduction programs. Strait Pharm. 2010;22(03):205–6.

Xu HJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different treatment schemes for acute cerebral infarction. Guangxi Med. 2012;34(12):1690–1.

Xu K. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three kinds of angiotensin II receptor antagonists for antihypertensive treatment. Pract J Cardiocereb Pulm Vasc Dis. 2014;22(01):81–2.

Xu XH. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of three medication schemes for gastric ulcer. West China Med. 2006;01:39.

Xu ZR, Ji QH, Xu F, Ye Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of insulin aspart and human insulin during meals in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Chin J New Drugs. 2014;23(18):2174–9.

Yan LH, Yu Q. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of peptic ulcer treatment. China Pharm. 2013;22(16):82–4.

Yang DZ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three treatment options for primary hypertension in community. Chin Med Guide. 2010;8(07):76–7.

Yang JN, Fei XW. The efficacy and pharmacoeconomic analysis of cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam in the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Chin School Doctor. 2014;28(10):794–5.

Yang SG, Zhang JH. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness analysis of moxifloxacin hydrochloride and ceftriaxone sodium combined with azithromycin in the treatment of moderate to severe elderly community-acquired pneumonia. Chin J New Drugs. 2009;18(10):962–4.

Yang SH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment plan for decompensated stage of hepatitis B liver cirrhosis. Chin Pharm Econ. 2014;9(02):9–10.

Yang XM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ligustrazine hydrochloride and ginkgo damol injection in the treatment of angina pectoris. J Clin Ration Use. 2011;4(22):44–5.

Yang XM, Wu QH, Liang D, Xiao XZ, Ma LY, Zheng C. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three programs for treating lower respiratory tract infection. China Med Herald. 2008;27:11–2.

Ying JB, Yang XP, Feng PY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of Marvelon and Daying-35 in the treatment of adolescent functional uterine bleeding. Strait Pharm. 2012;24(04):239–40.

You JF. Cost-effectiveness comparison of irbesartan tablets from different manufacturers in the treatment of essential hypertension. Strait Pharm. 2009;21(05):106–7.

Yu DM, Wu JM, Yu HD. Cost-benefit analysis of sequential treatment of cefuroxime sodium and cefixime in the treatment of pediatric infections. Jilin Med. 2010;31(22):3646–8.

Yuan HY, Ji P, Shi QP, Lin Y, Yi H, Li B. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cefmetazole and cefoperazone in the treatment of lower respiratory tract infections in children. China Pharm. 2010;19(09):44–5.

Yuan Y, Xie YC. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two treatments for community-acquired pneumonia. J North Sichuan Med Coll. 2015;30(03):291–4.

Zeng HS, Deng ZH, Ke YW. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three schemes in the treatment of infant bronchopneumonia with myocardial damage. Pract Clin Med. 2014;15(07):68–70.

Zeng ZQ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of L-amlodipine and losartan potassium in essential hypertension. Chin Foreign Med. 2013;32(16):15–6.

Zhang DF, Wang FS, Yu J. Economic evaluation of three drugs for treating lower respiratory tract infection. China Pharm Aff. 2009;23(08):826–8.

Zhang GY, Liang XM, Wang RM. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness analysis of two kinds of tamsulosin in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. China Pharm. 2012;21(17):40–1.

Zhang HL, Chen JH, Li HX. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three kinds of antibiotics in the treatment of acute cholecystitis. Eval Anal Drug Use Chin Hosp. 2007;06:447–8.

Zhang J, Liu SQ, Zhang J, Ban LY, Zhou T. Efficacy and cost-benefit analysis of different schemes for second-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;17(10):908–11.

Zhang JC, Li WD, Tan FL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of gatifloxacin and levofloxacin hydrochloride in the treatment of urinary system infections. J Pract Med Technol. 2007;04:404–5.

Zhang JF, Wen LY, Zhu MD, Chen JH, Yan XL, Yu LL, et al. Surveillance of imported schistosomiasis condition and cost-effectiveness analysis. Int J Epidemiol Infect Dis. 2007;034(003):163–5.

Zhang JJ, Chen ZQ. Economic comparison of different drugs in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Chin Clin Med. 2014;21(03):349–51.

Zhang LX, Bian L, Zhang JF, Shi XM, Wang YM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sequential treatment of onychomycosis with itraconazole combined with terbinafine. China Pharm. 2015;24(22):151–2.

Zhang QD. Cost-effectiveness analysis of proton pump inhibitor triple therapy to eradicate Helicobacter pylori. China Pharm. 2007;03:48–9.

Zhang XM, Guan XY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 4 kinds of antibacterial drugs in the treatment of lower respiratory tract infections. Chin Med Guide. 2013;11(36):421–3.

Zhang Y, Lin CW, Chen DH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three hypertension treatment programs. Qilu Pharm. 2010;29(12):729–31.

Zhang Y, Wu YQ, Qin XY, Ren T, Tao QS, Wu T, et al. Evaluation of the long-term efficacy and safety of Jiangya No. 0 in the treatment of essential hypertension. Chinese Community Physician (medical major). 2008;13:19–21.

Zhang YE, Jin CF. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two combined medication regimens in the treatment of ischemic cerebral infarction. Chin Pharm. 2008;02:86–8.

Zhang YE, Wei CX. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two drug regimens in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Chin Licens Pharm. 2008;7(05):24–6.

Zhang YT, Li J. Economic evaluation of fleroxacin and ofloxacin in the treatment of urinary tract infections. China Pharm. 2007;07:36–7.

Zhao B, Shi L, Yu QL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three treatments for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heilongjiang Med. 2009;22(03):391–2.

Zhao BK, Jia JH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 4 medication regimens in the treatment of essential hypertension. Chin Pharm. 2008;17:1287–9.

Zhao XH, Li ZH. Economic evaluation of three hypertension treatment programs. China Pharm. 2010;19(21):55–7.

Zhao ZY, Zheng XH, Gao L, Shi GL, Zhang HJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of capecitabine combined with oxaliplatin in the treatment of advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer. Chin Pharm. 2014;25(46):4321–5.

Zheng HQ. Pharmacoeconomics analysis of three kinds of antibiotics in treatment of lower respiratory tract infection. Strait Pharm. 2009;21(06):205–7.

Zheng HZ. Moxifloxacin and levofloxacin in the treatment of urinary tract infections and cost-effectiveness analysis. China Pharm. 2010;19(07):62–3.

Zheng JH, Wang JC, Yang DK. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two antiviral treatments for chronic hepatitis B. Chin J Hosp Pharm. 2011;31(06):513–4.

Zhou AL, Sun JS, He JY. Thoracic catheterization combined with sodium hyaluronate to prevent tuberculous pleurisy and pleural hypertrophy: cost-effectiveness analysis. Chin J Tuberc. 2009;31(08):487–90.

Zhou H. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of preventive application of antibiotics in total abdominal hysterectomy. Eval Anal Drug Use Chin Hosp. 2009;9(12):925–7.

Zhou HQ. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of three different anti-fungal infections: itraconazole, terbinafine and fluconazole. China Contin Med Educ. 2015;7(11):239–40.

Zhou L, Liu JX, Li HG, Zhao LH, Liu LS, Sun JL, et al. Comparative study on the clinical efficacy and cost-benefit of two regimens in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Shanghai J Tradit Chin Med. 2012;46(05):21-3+52.

Zhu BL, Wang Z, Yin WY, Ye Q. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of two kinds of brain protective agents in the treatment of cerebral hemorrhage. Strait Pharm. 2010;22(09):196–7.

Zou R, Deng SJ, Li ZL. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three schemes for treating infant pneumonia. Chin Med Guide. 2011;9(22):284–5.

Zuo ZY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of three kinds of traditional Chinese medicine injections in treating exogenous fever. Mod Med Health. 2008;20:3136–7.

Bai Y, Zhao Y, Wang G, Wang H, Liu K, Zhao W. Cost-effectiveness of a hypertension control intervention in three community health centers in China. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(3):195–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131912470459.

Chen S, Li J, van den Hoek A. Universal screening or prophylactic treatment for Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women seeking induced abortions: which strategy is more cost-effective? Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(4):230–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.olq.0000233739.22747.12.

Chen XZ, Jiang K, Hu JK, Zhang B, Gou HF, Yang K, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(17):2715–22. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.2715.

Chen ZY, Chen LL, Wu LM. Transcatheter amplatzer occlusion and surgical closure of patent ductus arteriosus: comparison of effectiveness and costs in a low-income country. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30(6):781–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-009-9440-3.

Deng J, Gu SY, Shao H, Dong HJ, Zou DJ, Shi LZ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of exenatide twice daily (BID) vs insulin glargine once daily (QD) as add-on therapy in Chinese patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled by oral therapies. J Med Econ. 2015;18(11):974–89. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2015.1067622.

Duan L, Huang M, Yan H, Zhang Y, Gu F. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two therapeutic schemes in the treatment of acromegaly: a retrospective study of 168 cases. J Endocrinol Invest. 2015;38(7):717–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-015-0242-6.

Gu DF, He J, Coxson PG, Rasmussen PW, Huang C, Thanataveerat A, et al. The cost-effectiveness of low-cost essential antihypertensive medicines for hypertension control in china: a modelling study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(8): e1001860. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001860.

Han YF, Xiao HB, Zhou Z, Yuan MQ, Zeng YB, Wu H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of strategies introducing integrated F-18-FDG PET/CT into the mediastinal lymph node staging of non-small-cell lung cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2015;36(3):234–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/Mnm.0000000000000247.

Huang LH, Zhang L, Tobe RYG, Qi FH, Sun L, Teng Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of neonatal hearing screening program in China: should universal screening be prioritized? BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-97.

Huang WD, Liu GX, Zhang X, Fu WQ, Zheng S, Wu QH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening protocols in urban Chinese populations. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10): e109150. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109150.

Jiang K, Chen XZ, Xia Q, Tang WF, Wang L. Cost-effectiveness analysis of early veno-venous hemofiltration for severe acute pancreatitis in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(12):1872–7. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1872.

Li F, Jiang F, Jin XM, Shen XM. Cost-efficiency assessment of 3 different pediatric first-aid training models for caregivers and teachers in Shanghai. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(5):357–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e318216a5f0.

Liu SX, Chen F, Ding XY, Zhao ZZ, Ke W, Yan Y, et al. Comparison of results and economic analysis of surgical and transcatheter closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defect. Eur J Cardio Thorac. 2012;42(6):E157–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezs519.

Liubao P, Xiaomin W, Chongqing T, Karnon J, Gannong C, Jianhe L, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of adjuvant therapy for operable breast cancer from a Chinese perspective: doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide versus docetaxel plus cyclophosphamide. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(10):873–86. https://doi.org/10.2165/11314750-000000000-00000.

Lu Z, Yi X, Feng W, Ding J, Xu H, Zhou X, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic surgery versus laparotomy for patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer: experience from an institute in China. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(7):1011–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01820.x.

Ma YY, Ying XH, Zou HD, Xu XC, Liu HY, Bai L, et al. Cost-utility analysis of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment surgery in Shanghai, China. Ophthal Epidemiol. 2015;22(1):13–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/09286586.2014.884601.

Meng LP, Xu HQ, Liu AL, van Raaij J, Bemelmans W, Hu XQ, et al. The costs and cost-effectiveness of a school-based comprehensive intervention study on childhood obesity in China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10): e77971. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077971.

Pan Y, Wang A, Liu G, Zhao X, Meng X, Zhao K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel-aspirin versus aspirin alone for acute transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3): e000912. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.114.000912.

Pan YS, Chen QD, Zhao XQ, Liao XL, Wang CJ, Du WL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of thrombolysis within 4.5 hours of acute ischemic stroke in China. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e110525. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110525.

Pang Y, Li Q, Ou XC, Sohn H, Zhang ZY, Li JC, et al. Cost-effectiveness comparison of genechip and conventional drug susceptibility test for detecting multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7): e69267. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069267.

Shen FH, Liu HB, Yuan JX, Han B, Cui K, Ding Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis prevention based on its predicted incidence within the Datong Coal Mine Group in China. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6): e0130958. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130958.

Sun DW, Du JW, Wang GZ, Li YC, He CH, Xue RD, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of plasmodium falciparum malaria elimination in Hainan Province, 2002–2012. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(6):1240–8. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0486.

Sun X, Guo LP, Shang HC, Ren M, Wang Y, Huo D, et al. The cost-effectiveness analysis of JinQi Jiangtang tablets for the treatment on prediabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter design. Trials. 2015;16:496. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0990-9.

Tan CQ, Peng LB, Zeng XH, Li JH, Wan XM, Chen GN, et al. Economic evaluation of first-line adjuvant chemotherapies for resectable gastric cancer patients in China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12): e83396. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083396.

Wang JW, Dong MH, Lu Y, Zhao X, Li X, Wen AD. Impact of pharmacist interventions on rational prophylactic antibiotic use and cost saving in elective cesarean section. Int J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;53(8):605–15. https://doi.org/10.5414/Cp202334.

Wang MA, Moran AE, Liu J, Coxson PG, Heidenreich PA, Gu DF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of optimal use of acute myocardial infarction treatments and impact on coronary heart disease mortality in China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual. 2014;7(1):78–85. https://doi.org/10.1161/Circoutcomes.113.000674.

Wang SH, Moss JR, Hiller JE. The cost-effectiveness of HIV voluntary counseling and testing in China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011;23(4):620–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539511412576.

Wang ZH, Gao QY, Fang JY. Repeat colonoscopy every 10 years or single colonoscopy for colorectal neoplasm screening in average-risk Chinese: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(5):1761–6. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.5.1761.

Wen F, Yao K, Du ZD, He XF, Zhang PF, Tang RL, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of colon cancer treatments from MOSIAC and No. 16968 trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(47):17976–84. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17976.

Wu B, Chen H, Shen J, Ye M. Cost-effectiveness of adding rh-endostatin to first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in China. Clin Ther. 2011;33(10):1446–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.09.016.

Wu B, Dong B, Xu Y, Zhang Q, Shen J, Chen H, et al. Economic evaluation of first-line treatments for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis in a health resource-limited setting. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3): e32530. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032530.

Wu B, Li T, Cai J, Xu Y, Zhao G. Cost-effectiveness analysis of adjuvant chemotherapies in patients presenting with gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:984. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-984.

Wu B, Li T, Chen HF, Shen JF. Cost-effectiveness of nucleoside analog therapy for hepatitis B in China: a Markov analysis. Value Health. 2010;13(5):592–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00733.x.

Wu B, Miao Y, Bai Y, Ye M, Xu Y, Chen H, et al. Subgroup economic analysis for glioblastoma in a health resource-limited setting. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4): e34588. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034588.

Wu B, Shen J, Cheng H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different rescue therapies in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B in China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:385. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-385.

Wu B, Song Y, Leng L, Bucala R, Lu LJ. Treatment of moderate rheumatoid arthritis with different strategies in a health resource-limited setting: a cost-effectiveness analysis in the era of biosimilar. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(1):20–6.

Wu B, Wilson A, Wang FF, Wang SL, Wallace DJ, Weisman MH, et al. Cost effectiveness of different treatment strategies in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in china. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10): e47373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047373.

Xia H, Song YY, Zhao B, Kam KM, O’Brien RJ, Zhang ZY, et al. Multicentre evaluation of Ziehl-Neelsen and light-emitting diode fluorescence microscopy in China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(1):107–12. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.12.0184.

Xie Q, Wen F, Wei YQ, Deng HX, Li Q. Cost analysis of adjuvant therapy with XELOX or FOLFOX4 for colon cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(8):958–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12216.

Chen Y, Qian X, Li J, Zhang J, Chu A, Schweitzer SO. Cost-effectiveness analysis of prenatal diagnosis intervention for Down’s syndrome in China. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23:138–45.

Yan HJ, Zhang M, Zhao JK, Huan XP, Ding JP, Wu SS, et al. The increased effectiveness of HIV preventive intervention among men who have sex with men and of follow-up care for people living with HIV after “task-shifting” to community-based organizations: a “cash on service delivery” model in China. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7): e103146. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103146.

Yan X, Hu HT, Liu SZ, Sun YH, Gao X. A pharmacoeconomic assessment of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator therapy for acute ischemic stroke in a tertiary hospital in China. Neurol Res. 2015;37(4):352–8. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743132814y.0000000447.

Yang J, Jit M, Leung KS, Zheng YM, Feng LZ, Wang LP, et al. The economic burden of influenza-associated outpatient visits and hospitalizations in China: a retrospective survey. Infect Dis Poverty. 2015;4:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-015-0077-6.

Yang J, Wei WQ, Niu J, Liu ZC, Yang CX, Qiao YL. Cost-benefit analysis of esophageal cancer endoscopic screening in high-risk areas of China. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(20):2493–501. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i20.2493.

Yang L, Christensen T, Sun F, Chang J. Cost-effectiveness of switching patients with type 2 diabetes from insulin glargine to insulin detemir in Chinese setting: a health economic model based on the PREDICTIVE study. Value Health. 2012;15(1 Suppl):S56–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.018.

Yuan ZW, Jiang WL, Bi J. Cost-effectiveness of two operational models at industrial wastewater treatment plants in China: a case study in Shengze town, Suzhou City. J Environ Manage. 2010;91(10):2038–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.05.016.

Zeng X, Peng LB, Li JH, Chen GN, Tan CQ, Wang SY, et al. Cost-effectiveness of continuation maintenance pemetrexed after cisplatin and pemetrexed chemotherapy for advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: estimates from the perspective of the chinese health care system. Clin Ther. 2013;35(1):54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.12.013.

Zhang C, Ke W, Gao Y, Zhou S, Liu L, Ye X, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of antiviral therapies for hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients in China. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35(3):197–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-015-0273-y.

Zhang J, Shi Q, Wang GZ, Wang F, Jiang N. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy and shock wave lithotripsy in the management of ureteral calculi in eastern China. Urol Int. 2011;86(4):470–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000324479.

Zhang PF, Yang Y, Wen F, He XF, Tang RL, Du ZD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib as a first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroen Hepat. 2015;27(7):853–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/Meg.0000000000000373.

Zhang XG, Zhang ZL, Hu SY, Wang YL. Ultrasound-guided ablative therapy for hepatic malignancies: a comparison of the therapeutic effects of microwave and radiofrequency ablation. Acta Chir Belg. 2014;114(1):40–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015458.2014.11680975.

Zhang Y, Sun J, Pang Z, Gao W, Sintonen H, Kapur A, et al. Evaluation of two screening methods for undiagnosed diabetes in China: an cost-effectiveness study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2013;7(4):275–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2013.08.003.

Zhang Z, Zhai J, Wei Q, Qi J, Guo X, Zhao J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of psychosocial intervention for early stage schizophrenia in China: a randomized, one-year study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0212-0.

Zhou J, Ma X. Cost-benefit analysis of craniocerebral surgical site infection control in tertiary hospitals in China. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9(2):182–9. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.4482.

Zhou L, Situ SJ, Feng ZJ, Atkins CY, Fung ICH, Xu Z, et al. Cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies for annual influenza vaccination among children aged 6 months to 14 years in four provinces in China. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1): e87590. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087590.

Zhu J, Li T, Wang XH, Ye M, Cai J, Xu YJ, et al. Gene-guided gefitinib switch maintenance therapy for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer: an economic analysis. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-39.

Zhuang GH, Pan XJ, Wang XL. A cost-effectiveness analysis of universal childhood hepatitis A vaccination in China. Vaccine. 2008;26(35):4608–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.086.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS)–explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(2):231–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002.

Beck JR, Pauker SG. The Markov process in medical prognosis. Med Decis Mak. 1983;3(4):419–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X8300300403.

O’Mahony JF, Newall AT, van Rosmalen J. Dealing with time in health economic evaluation: methodological issues and recommendations for practice. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(12):1255–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0309-4.

Liang JJ, Zou DJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of combined use of sitagliptin phosphate in type 2 diabetic patients with poorly controlled metformin. Shanghai Med. 2013;36(05):414–7.

Qin XM, Xiang Q, Zhou J, Xu J, Zhang X. Cost-utility analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and traditional open cholecystectomy. Chin Gen Pract. 2014;17(33):3938–43.

Lin XL, Li Z, Xie HY. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two treatments for Helicobacter pylori-related peptic ulcer. Guangdong Med. 2012;33(06):844–6. https://doi.org/10.13820/j.cnki.gdyx.2012.06.021.

An ZP, Wu JL, Zhou YY, He YY, Duan JG. Efficacy and health economic evaluation of stroke unit. Chin J Rehabil Med. 2008;03:225–7.

Liu JY, Ji WY, Wu J. Cost-benefit analysis of vaccination against pneumonia polysaccharides in the elderly in Beijing. Chin Public Health. 2011;27(2):191–3.

Liu CM. Moist healing therapy of pressure ulcers and cost-benefit analysis. Nurs Pract Res. 2008;5(2):19–20.

Liu ZR, Wei WQ, Huang YQ, Qiao YL, Wu M, Dong ZW. Economic evaluation of early diagnosis and early treatment of esophageal cancer. Chin J Cancer. 2006;25(2):200–3.

Zhang X, Wu H, Ran CF, Liu LP, Zhang ZQ, Wang SD, et al. Cost-effectiveness study of rehabilitation treatment of hand trauma Chinese. J Rehabil Med. 2009;24(1):33–6.

Feng H, Song GH, Yang J, Hao CQ, Wang M, Li BY, et al. Health economics evaluation of the appropriate age of endoscopic screening for lifetime one-time endoscopic screening in China’s rural areas with high risk of esophageal cancer. Chin J Oncol. 2015;37(6):476–80.

Ma YX, Huang Y, Zhao HY, Liu JL, Chen LK, Wu HY, et al. The cost-effectiveness analysis of gefitinib or erlotinib in the treatment of advanced EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer patients. Chin J Lung Cancer. 2013;16(4):203–10. https://doi.org/10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2013.04.06.

Gao JY, Wang YH, Yang L, Qi LL, Huang QH, Zhao H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the first choice of sodium valproate or levetiracetam for newly diagnosed children with epilepsy in China. Chin J Pract Pediatr. 2013;28(1):42–7.

Wu W, Zhang QY, Wu YB, Peng JP, Xie YQ, Xia FF, et al. Clinical efficacy and health economic evaluation of ultra-early thrombolytic therapy for acute cerebral infarction. Chin Gen Pract. 2013;16(4):1366–8.

Li XJ, Hu SL, Cheng YN, Zuo YL, Wang YH, Ye L, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of non-drug comprehensive intervention of hypertension in community. China’s Health Econ. 2011;30(2):48–50.

Xu H, Zhao FH, Gao XH, Hu SY, Chen JF, Liu ZH, et al. The health economics evaluation of cervical cancer screening methods and the screening start age. Chin J Epidemiol. 2013;34(4):399–403.

Cui LJ, Hu YS, Shen GG, Zhang AM, Zhang YP, Chen HF, et al. Health economics evaluation of tertiary rehabilitation treatment in community after stroke. Chin J Rehabil Med. 2009;24(12):1087–91.

Wu Y, Zhang XL. Comparative study on the cost-effectiveness of four dosing regimens in the treatment of acute cerebral infarction. Chin J Biochem Pharm. 2010;31(1):57–8.

Yan TS, Sun WP, Liu J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fovir dipivoxil in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Chin J Hosp Pharm. 2014;34(17):1499–501.

Liu YM, Wang WY. Comparative study on the efficacy and pharmacoeconomics of two plans in the treatment of community acquired pneumonia. Chin Gen Pract. 2013;16(11A):3735–7.

He Q, Zhang B, Li YY, Bai YL, Wu Y, Hu YS. Health economics evaluation of different rehabilitation schemes for treatment of hemiplegia patients after stroke. Chin J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;35(4):303–6.

Yuan Y. Evaluation of the screening effect of high-risk groups of gastric cancer in Zhuanghe area of Liaoning Province from 1997 to 2011. Chin J Oncol. 2012;34(7):538–42.

Long TF, Peng XX, Wu MH, Zhang SW, Wang JD, Zhang WY, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cervical cytology and HR_HPV testing in screening cervical lesions. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat. 2012;19(22):1690–5. https://doi.org/10.16073/j.cnki.cjcpt.2012.22.009.