Abstract

Background

In India, more than two-thirds of the total health expenditure is incurred through out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) by households. Morbidity events thus impose excessive financial risk on households. The Sustainable Development Goals Target 3.8 specifies financial risk protection for achieving universal health coverage (UHC) in developing countries. This study aimed to estimate the impact of OOPE on catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) and impoverishment effects by types of morbidity in India.

Methods

Data came from the 75th round of the National Sample Survey (NSS) on the theme ‘Social consumption in India: Health’, which was conducted during the period from July 2017 to June 2018. For the present study, 56,722 households for hospitalisation, 29,580 households for outpatient department (OPD) care and 6285 households for both (OPD care and hospitalisation) were analysed. Indices, namely health care burden, CHE, poverty head count ratio and poverty gap ratio using standard definitions were analysed.

Results

Households with members who underwent treatment for cancers, cardiovascular diseases, psychiatric conditions, injuries, musculoskeletal and genitourinary conditions spent a relatively high amount of their income on health care. Overall, 41.4% of the households spent > 10% of the total household consumption expenditure (HCE) and 24.6% of households spent > 20% of HCE for hospitalisation. A total of 20.4% and 10.0% of households faced CHE for hospitalisation based on the average per capita and average two capita consumption expenditure, respectively. Health care burden, CHE and impoverishment was higher in households who sought treatment in private health facilities than in public health facilities.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that there is an urgent need for political players and policymakers to design health system financing policies and strict implementation that will provide financial risk protection to households in India.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Findings from this study show that the out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) in health care has exposed households with morbidity conditions to catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) and impoverishment. |

Along with access to health insurance, there is greater need for price regulations for treatment in private health facilities in order to reduce the financial risk among poorer populations. |

Policy makers need to design and strictly implement suitable health system financing policies that will provide financial risk protection to households. |

1 Introduction

India is currently experiencing a triple burden of disease, that is, rising non-communicable diseases (NCDs), the unfinished agenda of infectious and communicable disease control and diseases arising due to climate change [1, 2]. Approximately 4.7 million deaths (49% of all-cause mortality) occurred in India in 2017 due to NCDs [3]. Communicable diseases contribute to 27.5% of all the deaths as per the Global Burden of Disease Study [1]. Climate change is expected to affect human health in India through factors such as infectious diseases (malaria, chikungunya etc.) and water-borne illnesses. In India, for the year 2016–17 as per the National Health Accounts, the government health expenditure (GHE) including capital expenditure was 1.2% of GDP, household out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) on health represents 63.2% of the total health expenditure (THE), and health insurance expenditure is only around 7.6% of current health expenditure [4]. The overall burden of these diseases coupled with low public health spending, high OOPE and lack of protection against catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) could lead to devastating effects on human lives in India [5, 6]. An estimated 32–39 million people are pushed into poverty due to health care expenditure in India each year [7,8,9].

The impact of the financial burden across various disease categories in India is poorly researched. One of the main gaps is the impoverishment impact of OOPE on households due to utilisation of outpatient care, hospitalisation or both, across various disease categories. A few studies have studied disease-specific OOPE on hospitalisation [5]. Other studies have focused on CHE and impoverishment effects of OOPE. However, these studies are either focused on maternal health [10], or specific disease categories such as NCDs [11, 12], cancer [13], disability [14], or for a specific state [15]. One study did look into all morbidities (NCDs and infectious diseases) but used data from a previous round of National Sample Survey (NSS) 2004 and did not report financial burden on households for outpatients and hospitalised cases separately [6].

This study aimed to estimate the impact of OOPE on CHE and impoverishment effects by various disease types in India. This information would be helpful in formulating social protection strategies to increase financial risk protection for households affected by various disease ailments in India.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

The current study uses national representative cross-sectional survey household data from the 75th round of the NSS on the theme ‘Social consumption in India: Health’, which was conducted during the period July 2017–June 2018 [16]. NSS 75th round covered 14,258 village/urban blocks (8077 rural villages, 6181 urban blocks), 113,823 households (64,552 rural, 49,271 urban) and 555,115 individuals (325,883 rural; 229,232 urban). This study utilised data from all of the 56,722 households whose family members sought treatment from a hospital (any member hospitalised in the last 365 days), the 29,580 households receiving outpatient department (OPD) care (any member treated in an OPD in the last 15 days) and the 6285 households that reported both (i.e. reported treatment of disease conditions from OPDs and hospitals). The NSS adopted a stratified multi-stage sampling design. In rural areas, sample villages and in the urban areas urban blocks were chosen with Probability Proportional to Size with Replacement (PPSWR) as the first stage. The sample households were chosen by Systematic Random Sampling without Replacement (SRSWOR) as the second stage. The details of the survey methodology are described in the NSS report [16]. Box 1 provides the disease conditions identified using self-reporting in the study samples [16].

2.2 Measuring Out-of-Pocket Expenditure (OOPE) for Health Care

The NSS collected data on expenditure on medicine, consultation fees, hospital stay charges, other medical expenses such as physiotherapy, blood, oxygen, attendant charges and other non-direct costs included transport for patients and other accompanying persons, food-related expenses, lodging charges and others. In this study, OOPE for health expenditure was calculated by deducting any reimbursement amount from total health expenditure (direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs and other indirect costs for health care expenditure), a method used by many previous studies [4, 9, 10]. The NSS captures OPD care for the last 15 days and hospitalisation expenditure for last 365 days preceding the survey period. This was converted to monthly OOPE by multiplying OPD care OOPE by a factor of 2 and by dividing hospitalisation OOPE by 12. Respective sample weights were then applied in the calculation of the results.

2.3 Share of OOPE on Household Consumption Expenditure

The cost of treatments for households as a share of total consumption expenditure of households was calculated, as indicated by many of the previous studies [13, 14]. The expenses incurred for treatment at OPDs, hospitals and both were used for analysis using the following formula:

2.4 Measuring Catastrophic Health Expenditure (CHE)

A household was considered to be exposed to CHE if OOPE on health care exceed α% threshold of households’ income [17]. In existing literature, there is no consensus on the threshold of α% threshold [18, 19]. Most studies have defined CHE as OOPE on health expenditure exceeding 40% of a household’s total non-food consumption expenditure or health expenditure exceeding 10% of a household’s total consumption expenditure [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

We used the ratio method for estimating CHE. In this method a household faced CHE if the net OOPE exceeded 10% or 20% of the total household consumption expenditure (HCE).

2.4.1 First Approach

When OOPE exceeded 10% and 20% of an HCE, it was considered CHE, which is a standard benchmark used in literature [27, 28].

2.4.2 Second Approach

The second approach uses average HCE per person and per two persons of the household. We found this approach relevant since household sizes may vary although HCE may remain the same. Thus, a household with more members may face higher CHE than a household with fewer members, although the HCE is the same [29].

where α is the average household consumption expenditure per person and β is the average household consumption expenditure for two members of the household [29].

2.5 Measuring Impoverishment Impact of OOPE on Health Care

Households with net total expenditure on OOPE less than the poverty line (PL) are measured using poverty head count. To calculate the poverty line, we used per capita household monthly expenditure at 972 Indian Rupees (INR) in rural areas and INR 1407 in urban areas as per recommendation by the Rangarajan committee [30]. The following formula was used for the ith household:

The poverty head count ratio (PHCR) is the percentage of households who fall below the poverty line due to OOPE [25,26,27].

(N = number of households)

The percentage deficit from the poverty line of those households that have become poor due to OOPE is quantified using the poverty gap, and the poverty gap ratio measures the percentage deficit from the poverty line of households that have become poor due to OOPE as a proportion of all the households in the population [19, 26,27,28].

(N = number of households)

All the expenditures were converted to December 2019 prices with inflation adjustments using the consumer price index including poverty line thresholds [31, 32].

2.6 Statistical and Econometric Model

Descriptive statistics, bivariate estimates and multivariate models were performed on expenditure data. In the first part of the analysis, descriptive analysis was carried out to describe morbidity distribution in households. In the second step, bivariate analyses were carried out to discover the impact of OOPE, health care burden (share of OOPE on total HCE), CHE and impoverishment effect by type of morbidity and health facilities (public and private). In the third step of the analysis, logistic regression analysis was carried out to estimate the effect of different morbidity conditions on CHE and the impoverishment impact. In order to take into account the survey design (i.e. sampling weights with clustering and strata), while estimating bivariate and multivariable statistics, the SVY command was used in STATA 13.1. All expenditures are reported in Indian Rupees (INR). The NSS captured the monthly consumption expenditure (MCE) based on the components of household consumption expenditure including food, beverages, durable, semi durable and non-durable household goods and other frequently purchased goods and services. For this study we have converted the MCE into an adult equivalent household consumption expenditure. This study used the adult equivalent scale that has been used in many previous studies [17, 33, 34] (Table 1).

3 Results

3.1 Distribution of Households by Type of Morbidity

Table 2 reports the percentage distribution of households whose family members sought treatment from hospitalisation care, OPD care and both by type of morbidity. Nearly 31% of households sought hospitalisation care, 35% consulted for OPD care and 20% of the households had undergone both due to various morbidities. The proportion of households with members with injuries (12.4%) was the second highest cause for hospitalisation care after infections (31.4%), followed by gastro-intestinal conditions (10.4%) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (8.4%). For OPD, households with endocrine disorders (15.3%) were the second most common reason for seeking treatment after infections (33.2%), followed by CVDs (11.6%) and musculoskeletal conditions (10.1%). CVD (18.4%) was the second highest cause after infections (20.3%) for households who sought treatment from both, followed by endocrine (10.4%) and psychiatric disorders (9.7%).

3.2 OOPE on Health Care by Type of Morbidity

Table 3 reports the average monthly OOPE of households from hospitalisation, OPD care and both by type of morbidity. Overall, only 9.15%, 0.64% and 5.57% of the total OOPE were reimbursed for hospitalisation, OPD care and both, respectively. Cancer was the highest cause of OOPE for health care across hospitalisation, OPD care and both, followed by CVDs for hospitalisation, genitourinary conditions for OPD care and gastro-intestinal issues for both.

3.3 Share of OOPE on Households’ Consumption Expenditure

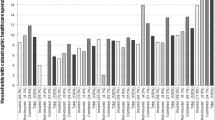

The proportion of OOPE on health care of total household consumption expenditure and the estimated health care burden by type of morbidity is reported in Table 3. The highest health care burden was reported by households with any member suffering from cancer across hospitalisation, OPD care and both. For hospitalisation, psychiatric (25.8%) and musculoskeletal (25.8%) conditions were the second highest causes for health care burden followed by CVDs (24.9%) and injuries (23.7%). Genitourinary issues (44.0%), obstetrics (42.9%), injuries (34.6%) and blood disorders (38.0%) were the top conditions after cancer contributing to health care burden in households for OPD. Households where one or more members received treatment in both (hospitalisation care and OPD care) were highest for cancer (123.8%), followed by gastro-intestinal conditions (98.8%), obstetrics (90.8%), injuries (81.8%) and musculoskeletal complaints (68.4%). Health care burden was higher in the households that sought treatment in private hospitals compared with public hospitals (Fig. 1). Health care burden was about five times higher for hospitalisation care, two times higher for OPD care and more than two times higher for both (hospitalisation and OPD care) among those households whose family members sought treatment in private hospitals compared with public hospitals (Supplementary Appendix Tables 1, 2 and 3, see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]).

3.4 Exposure to CHE

Table 4 provides analysis of CHE by type of morbidity using 10% and 20% thresholds as well as the average household consumption expenditure per person and the average household consumption expenditure per two members of the household. Results show that 41.4% and 24.6% of the households incurred CHE due to hospitalisation based on 10% and 20% thresholds, respectively. For OPD care, 22.5% of the households’ OOPE exceeded the PHCE of one household member, and in 9.8% of households, of two household members. Eighty-one percent of households at the 10% threshold and 64.6% of households based on a 20% threshold were exposed to CHE due to both hospitalisation and OPD care. OOPE exceeded PHCE of one or two household members in 58.5% and 38.7% of households, respectively. Households containing members with cancer reported the highest exposure to CHE, while those with infections reported the lowest. CHE was about seven times higher for hospitalisation care and two times higher for OPD care and both for family members who sought treatment in private health facilities compared with those who visited public health facilities (Supplementary Appendix Tables 1, 2 and 3, see ESM).

3.5 Odds of Households Incurring CHE Due to OOPE in Health Care

The odds of incurring CHE for cancer was significantly higher for hospitalisation care (odds ratio [OR] 11.49; 95% confidence interval [CI] 9.21–14.25) and both (hospitalisation and OPD care) (OR 9.16; 95% CI 4.74–17.7) when compared with infections (reference value) (Table 5). The likelihood of CHE due to CVDs was three times higher for hospitalisation care (OR 2.96; 95% CI 2.55–3.44). Further, odds of incurring CHE were significantly higher among households where any member received treatment for injury from hospitalisation care (OR 3.98; 95% CI 2.61–6.05), OPD care (OR 3.24; 95% CI 1.94–5.41) and both (OR 1.68; 95% CI 0.98–3.25) in comparison with communicable diseases.

3.6 Impoverishing Effects of OOPE in Health Care

About 14.1%, 16.4% and 39.1% of the households fell below the poverty line due to health care expenditure for hospitalisation care, OPD care and both, respectively (Table 6). The highest PHCR was seen among cancer patients across all types of treatment. The percentage of households falling below the poverty line was higher among those households where any member had one of the following conditions: cancers (31.4%), other (19.6%), psychiatric (22.9%), CVD (19.2%) and injuries (20.3%) for hospitalisation care while the percentage of households falling below the poverty line was higher among those with cancers (15.5%), obstetrics (49.0%), genitourinary (32.8%), blood disorders (32.4%), other conditions (24.3%) and injuries (19.9%) for OPD care. PHCR was highest among households with members treated for cancers (235.5%), genitourinary (71.9%), blood disorders (70.2%), gastro-intestinal (155.7%), injuries (96.2%) and psychiatric conditions (53.1%) for both hospitalisation care and OPD care. The poverty gap ratio is significantly higher in cancers, injuries, gastro-intestinal, obstetrics and genitourinary conditions irrespective of mode of treatment. PHCR and the poverty gap ratio were found to be high among households whose sought treatment in private health care facilities in comparison with those utilising public health facilities (Supplementary Appendix Tables 1, 2 and 3, see ESM).

3.7 Odds of Falling Below the Poverty Line Due to OOPE in Health Care

Table 7 presents the results of logistic regression for predicting the effect of different morbidity conditions on impoverishment due to OOPE on health care. The odds of falling below the poverty line due to health care expenditure for cancer were significantly higher for hospitalisation care (OR 7.670; 95% CI 5.878–10.008), OPD care (OR 1.348; 95% CI 1.014–1.791) and both (OR 6.359; 95% CI 3.754–10.774) compared with infections. Odds of falling below the poverty line were significantly higher for households with members receiving treatment for gastro-intestinal, blood disorders, psychiatric, injurious-skeletal, genitourinary, obstetrics and other disease conditions for hospitalisation care, OPD care and both (hospitalisation care and OPD care) compared with infections.

4 Discussion

Overall, 41.4% and 24.6% of the households faced CHE for hospitalisation care at the 10% threshold and 20% threshold, respectively, while 20.4% and 10.0% of the households had a catastrophic impact based on the modified approach of average per capita and average two capita monthly consumption expenditure, respectively. Our study results relating to financial catastrophe are similar to those of a previous study by Joe and Rajpal [29], which used similar methods to those reported in this paper. Their study indicated that 49.8% and 30.6% of the households faced CHE for hospitalisation at 10% and 20% thresholds, and 29.0% and 14.1% of the households faced CHE based on the average per capita and average two capita household consumption approach [29].

Our study results reveal that NCDs such as CVDs, cancers, injuries etc. have a higher catastrophic burden and resultant impoverishment in India. Catastrophic expenditure was found to be highest for cancer at 10% thresholds (70.0%) and at 20% thresholds (54.1%) for hospitalisation care. A similar finding was observed in a previous study where CHE was found to be higher (79%) due to cancer at 10% thresholds [13]. Households where one or more member received treatment for any type of morbidity, especially for cancers, CVDs, injuries and psychiatric, musculoskeletal and genitourinary conditions, spent an extensive amount of their income with comparable results shown in various previous studies [35,36,37]. The level of catastrophic expenditure varied across morbidity conditions and types of treatment by health care provider. In households with cancer and infectious patients, the catastrophic impact due to OOPE on health care was found to be higher for OPD care compared with hospitalisation.

Our study indicates that the health care burden, CHE and impoverishment effect was higher for patients seeking treatment in private health facilities than in public health facilities, as shown in various studies from India [5, 27], and the share was higher if patients were treated for cancers in India and Vietnam [4, 35]. Our analysis indicates that health care burden was almost five times higher for hospitalisation care and two times higher for OPD care if patients sought treatment in private health facilities rather than public health facilities. The impoverishment effect among the cancer patients irrespective of type of treatment was significantly higher if patients sought the treatment in a private health facility rather than a public health facility, which is consistent with findings from previous studies [6].

It is important to highlight the fact that even after the introduction of government social health insurance schemes, there is high prevalence of catastrophic expenditure due to hospitalisation in the public sector as per our study findings. There is therefore a need for customised disease-specific insurance packages designed for patients attending public health facilities.

Apart from cancer, care for injury leads to higher OOPE, catastrophic expenditure and impoverishment in households. Other studies have also reported higher OOPE for injuries compared with other diseases and ailments [11]. In view of the high burden of health care expenditure by households on injuries, there is need for effective implementation of preventive interventions such as regulations for vehicle and road safety, installation of speed bumps, breath testing and drowning prevention programmes, thus leading to significant cost savings through establishing preventive strategies [37].

The strength of our study derived from its use of national representative cross-sectional data from NSS 75th round. The NSS followed the standardised study design, and in particular, this survey focussed on health surveys based on the theme ‘Social consumption in India: Health’. The sample was very large, covering all the states and union territories of India, which offers generalisability to the study results. We have used monthly household consumption expenditure as a proxy variable for household income, as has been used in many previous studies [5, 6, 27, 29], which is a preferred measure because it is less prone to variation with less probability of being underreported or overreported when compared with income [35]. Besides the ratio approach of CHE, we also used the per capita household consumption expenditure approach, which is more likely to offer an improved estimate of household well-being [38].

While this study has several strengths, there are some limitations as well. First, since our study was based on household consumption expenditure, it could not measure the impact of indirect costs such as wage loss due to illness and wage loss of caregivers. Second, the NSS is a cross-sectional survey design and cross-examined expenditure data for 365 days preceding the survey time for hospitalisation care, hence recall bias could be a major limitation for expenditure data [39].

5 Conclusions and Future Research

Our study used the recent NSS survey for the year 2018 using household data, and reports OOPE, CHE and impoverishment effects for outpatient care, hospitalisation and both across all morbidities. We observed significant variation across morbidity conditions in health care burden, catastrophic expenditure and impoverishment effects due to out-of-pocket payments including those utilising private and public health facilities in India. Further research is needed to identify the unmet needs and coping strategies of people with various morbidity conditions due to financial limitations to seeking health care in India.

References

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Collaboration. Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990–2016 in the Global Burden of Disease study. Lancet. 2017;390(10111):2437–60.

Dhara VR, Schramm PJ, Luber G. Climate change and infectious diseases in India: implications for healthcare providers. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138(6):847–52.

Menon GRM, Singh L, Sharma P, Yadav P, Sharma S, Kalaskar S, et al. National burden estimates of healthy lives lost in India, 2017: an analysis using direct mortality data and indirect disability data. Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(12):E1675–84.

National Health Systems Resource Centre. National Health Accounts Estimates for India (2016–17). New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2019.

Kastor A, Mohanty SK. Disease-specific out-of-pocket and catastrophic health expenditure on hospitalization in India: do Indian households face distress health financing? PloS One. 2018;13(5):e0196106.

Sangar S, Dutt V, Thakur R. Comparative assessment of economic burden of disease in relation to out of pocket expenditure. Front Public Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00009.

Bonu S, Bhushan I, Rani M, Anderson I. Incidence and correlates of “catastrophic” maternal health care expenditure in India. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:445–56.

Garg CC, Karan AK. Reducing out-of-pocket expenditures to reduce poverty: a disaggregated analysis at rural-urban and state level in India. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:116–28.

Berman P, Ahuja R, Bhandari L. The impoverishing effect of healthcare payments in India: new methodology and findings. Econ Political Wkly. 2010;45:65–71.

Mohanty SK, Kastor A. Out-of-pocket expenditure and catastrophic health spending on maternal care in public and private health centres in India: a comparative study of pre and post national health mission period. Health Econ Rev. 2017;31(7):1–15.

Tripathy JP, Prasad BM, Shewade HD, Kumar AMV, Zachariah R, Chadha S, et al. Cost of hospitalisation for non-communicable diseases in India: are we pro-poor? Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21:1019–28.

Karan A, Engelgau M, Mahal A. The economic implications of non-communicable disease for India: Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) discussion paper. Washington: World Bank; 2010.

Rajpal S, Kumar A, Joe W. Economic burden of cancer in India: evidence from cross-sectional nationally representative household survey, 2014. PloS One. 2018;13(2):e0193320.

Mitra S, Findley PA, Rd EF, Hall D. Healthcare expenditures of living with a disability: total expenditures, out of pocket expenses and burden, 1996–2004. In: Discussion Paper No: 2008–18 September 2008. Fordham University, New York

Sahoo AK, Madheswaran S. Socio-economic disparities in health care seeking behaviour, health expenditure and its source of financing in Orissa. J Health Manag. 2014;16:397–414.

Government of India. Key indicators of social consumption in India: Health. New Delhi: National Sample Survey Organisation; 2019.

Kwesiga B, Zikusooka CM, Ataguba JE. Assessing catastrophic and impoverishing effects of health care payments in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:30.

Aregbeshola BS, Khan SM. Out-of-pocket payments, catastrophic health expenditure and poverty among households in Nigeria 2010. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7:798–806.

O’Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington: The World Bank; 2007.

Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362(9378):111–7.

Wagstaff A, Flores G, Smitz MF, Hsu J, Chepynoga K, Eozenou P. Progress on impoverishing health spending in 122 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6:e180–92.

Berki SE. A look at catastrophic medical expenses and the poor. Health Aff. 1986;5:138–45.

Russell S. The economic burden of illness for households in developing countries: a review of studies focusing on malaria, tuberculosis, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Tropic Med Hygiene. 2004;71(2_suppl):147–155.

Mataria A, Raad F, Abu-Zaineh M, Donaldson C. Catastrophic healthcare payments and impoverishment in the occupied palestinian territory. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2010;8:393–405.

Somkotra T, Lagrada LP. Which households are at risk of catastrophic health spending: experience in Thailand after universal coverage: exploring the reasons why some households still incur high levels of spending—even under universal coverage—can help policymakers devise solutions. Health Affairs. 2009;28(Suppl1):w467–78.

Van Doorslaer E, O’Donnell O, Rannan-Eliya RP, Somanathan A, Adhikari SR, Garg CC, et al. Catastrophic payments for health care in Asia. Health Econ. 2007;16:1159–84.

Kumar K, Singh A, Kumar S, Ram F, Singh A, Ram U, et al. Socio-economic differentials in impoverishment effects of out-of-pocket health expenditure in China and India: evidence from WHO SAGE. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0135051.

Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: with applications to Vietnam 1993–1998. Health Econ. 2003;12:921–33.

Joe W, Rajpal S. Unravelling the socioeconomic gradient in the incidence of catastrophic health care expenditure: a comment. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33:699–701.

Ravendran G. A review of Rangarajan committee report on poverty estimation. Indian J Hum Dev. 2016;10(1):85–96.

State Level Consumer Price Index (Rural/Urban) upto August 2018. Open Government Data (OGD) Platform India 2020, Apr 29. https://data.gov.in/resources/state-level-consumer-price-index-ruralurban-upto-august-2018. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Bajwala VR, John D, Rajasekar TD, Murhekar MV. Severity and costs associated with hospitalization for dengue in public and private hospitals of Surat city, Gujarat, India, 2017–2018. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2019;113:661–9.

Appleton S, Emwanu T, Kagugube J, Muwonge J. Changes in poverty in Uganda, 1992–1997: No. 1999–22. Oxford: Centre for the Study of African Economies; 1999.

Levine S. Exploring differences in national and international poverty estimates: is Uganda on track to halve poverty by 2015? Soc Indic Res. 2012;107(2):331–49.

Van Minh H, Xuan TB. Assessing the household financial burden associated with the chronic non-communicable diseases in a rural district of Vietnam. Global Health Act. 2012;5:1–7.

Deaton A, Zaidi S. Directrices para construir agregados de consumo para analizar el bienestar. Washington: Banco Mundial; 2002.

World Health Organization. Impact of out-of-pocket payments for treatment of non-communicable diseases in developing countries: a review of literature. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

Wesson HKH, Boikhutso N, Bachani AM, Hofman KJ, Hyder AA. The cost of injury and trauma care in low- and middle-income countries: review of economic evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:795–808.

Joe W. Distressed financing of household out-of-pocket health care payments in India: incidence and correlates. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30:728–34.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

The present study utilised household-level data from current NSS 75th round survey on the theme ‘Social consumption in India: Health’. The NSS is a countrywide large-scale population-based survey organisation under the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), Government of India. The NSS obtained ethical consensus from the review committee of the project while in the second stage, consent was taken from the respondents and duly undersigned, and only once he/she had agreed to participate in the study was any data collected. This study utilised secondary data that is accessible in the public domain and this dataset does not include any personal information of respondents.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Consent

The study results presented here do not involve human subject research, hence consent was not required.

Funding

Our study did not use any funding for conducting data acquisition and analysis.

Data availability statement

Our study utilised the NSS 75th round survey data, which is publicly accessible to individuals both countrywide and worldwide on http://www.mospi.gov.in/.

Author Contributions

JY conceived the idea for the study and developed the analysis plan. JY led the analysis and organised the first draft of manuscript. JY, DJ and GRM conducted data interpretation and manuscript writing. GRM, DJ and JY read and approved the preliminary manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the National Sample Survey Organisation (SSSO), MOSPI, India, for data collection and providing data for analysis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yadav, J., Menon, G.R. & John, D. Disease-Specific Out-of-Pocket Payments, Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Impoverishment Effects in India: An Analysis of National Health Survey Data. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 19, 769–782 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-021-00641-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-021-00641-9