Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the role of the Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination test (ACE-R) in the evaluation of cognitive status in migraineurs interictally. A total of 44 adolescent patients and 44 healthy controls, matched by age and gender, have undergone ACE-R testing. Migraineurs were additionally questioned about migraine aura features and presence of higher cortical dysfunctions (HCD) during an aura. According to the questionnaire results, patients were subsequently divided into HCD and Non-HCD group. ACE-R scores of migraine patients were significantly lower than in healthy controls (93.68 ± 3.64 vs 96.91 ± 2.49; t = 4.852, p < 0.001). Also, subscores of memory and verbal fluency were significantly higher in the control population. There was no correlation of HCD occurrence with cognitive examination score, although Non-HCD subgroup achieved better score (93.13 ± 3.91 vs 94.29 ± 3.30; t = 1.053, p = 0.298). Findings have shown that migraineurs get lower ACE-R test scores, with a tendency to have a poorer outcome in more complex aura. Also, our study has revealed that the ACE-R test is an easily administered test for brief assessment of cognitive status in migraineurs. Future perspectives could be further evaluation of ACE-R test in larger sample size and the impact of migraine with aura on cognitive function in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 (GBD2013), migraine is the sixth most common cause of adult disability worldwide [1]. Although the burden of migraine in adolescents is not easily assessed, it is considered to be substantial [2]. Taking into consideration the fact that the prevalence of migraine in adolescents around the world was 7–11 % [3], whereas 25 % of patients with migraine experienced an aura [4], disability among adolescent migraineurs is to be thoroughly investigated.

Long duration and frequent migraines can result in the absence from school and can cause problems within the family, as well as disturbance in social interactions [5]. While an impact of ictal migraine period on everyday life could be easily understood, the effect of migraine on interictal period is rather difficult to estimate [6]. Although it is proved that migraineurs develop impairment in certain cognitive functions [7–9], especially the decline in verbal performance and attention [10, 11], the association between the complexity of migraine attacks and interictal cognitive impairment is yet to be investigated. Moreover, the complexity of migraine aura showing great variety of cortical dysfunctions (such as speech difficulties, amnesia, dysgnosia and dyspraxia) is supposed to imply involvement and possible disorder of cortical regions other than occipital lobe [12, 13]. Therefore, the impact on cognition of these patients during the migraine-free days could be quite significant.

However, impaired cognitive performance in migraineurs with aura has not been reported in all the studies [14–16]. These discrepancies might be due to various reasons, e.g., insufficient sensitivity and specificity of the neuropsychological tests conducted or a selective investigation of only highly specific cognitive functions [11, 15].

The main problem with studies concerning the cognitive impairment in migraineurs is the fact that batteries, which assess multiple neuropsychological functions, are time consuming. In this study, the potential role of Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination test—ACE-R [17] (version validated for Serbian language) was considered for the above mentioned purpose. We chose this type of test because it broadly and briefly examines cognitive functions, which is suitable for comparing test results with impaired cognitive functions during complex migraine aura. A further advantage of the ACE-R is that it provides normative data for five subscales, enabling accurate analysis of the cognitive impairment patterns. Although it is known that ACE-R was developed for the diagnosis of dementia [17], its implementation can be also quite useful for mild cognitive impairment. Since ACE-R is an easily conducted test, there should be no obstacles in using it among adolescent population.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the cognitive profiles of adolescents affected by migraine with aura, and particularly to compare the results of the cognitive test of those who reported symptoms of higher cortical dysfunctions (HCD) during an aura and those who had no such symptoms.

Methods

Population

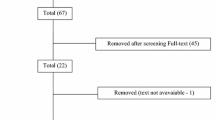

A total of 74 adolescents (aged 13–19 years at the moment of the randomization) having migraine with aura, who were admitted at the tertiary Clinic of Neurology and Psychiatry for Children and Youth, from the beginning of 2008 till the end of 2014 (7 years), were invited to take part in this study. The diagnosis was based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria (2004) [18]. All participants were neurologically and psychiatrically examined. Excluding criteria were: the occurrence of multiple types of headache, previous or current prophylactic therapy for migraine, motor aura symptoms, chronic migraine, concomitant neurological or psychiatric disorders, metabolic disease, changes in neuroradiological results and patients who did not respond to the call. Forty-four patients who had met the above mentioned inclusion criteria were enrolled in this study. A specially designed questionnaire [12] was used to collect the data on migraine aura features and HCD (e.g., language and memory impairment) during an aura (Table 1). The patients were interviewed by a doctor (I.P. or V.P.), experienced in headache research. According to the questionnaire results, patients were subsequently divided into HCD group (patients who reported at least one HCD symptom occurring twice or more in their migraine auras) and Non-HCD group (patients who reported only visual and somatosensory symptoms) for additional more profound analysis. All the participants and their parents gave their written informed consent. Afterwards, elementary and secondary school patients were selected. Then, 44 healthy controls were randomly selected and matched with migraineurs in terms of gender and age. Neurological and psychiatric diseases were excluded from healthy controls. Healthy controls were used as negative control for mild cognitive impairment testing. The Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination—revised test (ACE-R), was carried out at the clinic by physicians and consents obtained from participants and school authorities. Research protocol of this study was approved by the review board at the clinic where the research was conducted.

Cognitive evaluation

ACE-R test was administered to all the participants. The ACE-R is a comprehensive and easily administered pen and paper test of cognition which has been used in a number of neurodegenerative diseases [19]. The test takes between 14 and 20 min to perform and assesses five cognitive domains: attention/orientation (18 points), memory (26 points), verbal fluency (14 points), language (26 points) and visuospatial abilities (16 points), giving a total score of 100 points. ACE-R scores, subscores of memory and subscores of verbal fluency were compared among migraineurs and healthy controls. Subsequently, an influence of age at migraine onset, frequency of auras per year, aura duration, and HCD symptoms on ACE-R scores and subscores were analyzed. Migraineurs did not have migraine attack 7 days before nor 7 days after testing.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as arithmetic mean ± SD or as min–max values. The differences between ACE-R scores and subscores were tested for significance by the independent t test. Pearson correlation was used for comparing the patients’ age, aura duration, and aura frequence with ACE-R score and subscores. The significance level for the analysis was set beforehand at 5 % (p < 0.05).

Results

The study included 23 females and 21 males, aged 16.09 ± 2.05 (range 13–19) years, who all experienced migraine with aura. Average aura duration was 28.75 ± 16.25 min (range 5–75). Aura frequencies per year were highly diverse with average value of 6.68 ± 6.05 (2–27 migraine with aura attack). HCD symptoms during an aura were reported by 23 migraineurs. We also included 44 healthy controls, matched with migraineurs in terms of gender and age. ACE-R scores of migraine patients were significantly lower than in healthy controls (93.68 ± 3.64 vs 96.91 ± 2.49; t = 4.852, p < 0.001). Also, subscores of attention/orientation (17.2 ± 1.2 vs 17.9 ± 0.3; t = 3.889, p < 0.001), memory (24.8 ± 2.07 vs 25.59 ± 1.17; t = 2.216, p = 0.030) and verbal fluency (10.52 ± 1.55 vs 11.93 ± 1.63; t = 4.153, p < 0.001) were significantly higher in the control population. Subscores of language (25.5 ± 0.8 vs 25.6 ± 0.7; t = 0.585, p = 0.560) and visuospatial abilities (15.7 ± 0.8 vs 15.9 ± 0.5; t = 1.557, p = 0.124) did not significantly differ between those groups. There was neither correlation of patients’ age, HCD occurrence, aura duration and aura frequency with ACE-R score, nor with subscores of attention/orientation, memory, verbal fluency and language (Table 2). Also, there was no correlation of patients’ age, HCD occurrence and aura frequency with subscore of visuospatial abilities, but we found positive correlation of aura duration and subscore of visuospatial abilities,

Patients who reported HCD symptoms (labeled as HCD subgroup) did not differ significantly from migraineurs without the reported HCD symptoms (labeled as Non-HCD subgroup), although Non-HCD subgroup did achieve better score (93.13 ± 3.91 vs 94.29 ± 3.30; t = 1.053, p = 0.298). Subscores of attention/orientation, memory, verbal fluency, language and visuospatial abilities did not differ significantly between HCD and Non-HCD subgroups (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study was conducted among adolescent migraineurs with aura, who were treated at a dedicated neurology clinic for children and youth of a tertiary medical center. The interictal performance of migraineurs with aura on the cognitive test was studied. The findings showed that migraineurs got lower scores on ACE-R test. Moreover, with more complex aura there was a tendency toward a worse outcome on ACE-R test, but due to heterogeneity of aura characteristics it was difficult to establish a solid interpretation.

Despite continuous endeavoring for understanding the pathophysiological features of migraine and migraine aura, the knowledge of migraine aura effects on daily life are still not entirely understood, particularly with regard to the developmental age. In an Italian cross-sectional study, Parisi et al. suggested that the verbal skills of school-aged children with headache were supposed to be less developed compared to those having no headache [9]. Also, a longitudinal study conducted on migraineurs, aged from 3 to 26 years, has reported impaired verbal skills in migraineurs, in comparison with the control healthy group [11]. This subtle verbal deficits exhibited by migraineurs have a tendency to affect both high school grades and examination scores in the future [11], but not having any significant influence on general intellectual functioning [8]. It is also shown that during a headache-free period migraineurs with aura were slower than controls in performing tasks requiring selective attention [20]. Contrary to these findings, some study results [8, 11, 21–23] imply no statistically significant impact of headache on patients’ school work or working memory. In the present study, we did not have access to school activities, although it was shown that patients with migraine with aura got lower results on the cognitive test. Our finding is in line with the results reported by Dzoljic et al. who surveyed 245 migraineurs among 1943 female university-aged (18–28 years) individuals making a conclusion that having a migraine makes an adolescent more susceptible to worse outcome on cognitive test [24]. However, this study is not directly comparable to ours because of the differences in the characteristics of the population: older age, less severe migraine and exclusivity of a female gender.

Past studies showed inconsistent test results of immediate and delayed memory at baseline in migraineurs [14, 16, 25]. Our results show significantly lower ACE-R scores of migraineur patients compared to healthy controls, with the accent on impaired memory, attention and verbal fluency capabilities. The fact that there was no correlation between ACE-R score, on the one side, and patients’ age, HCD occurrence, aura duration and aura frequence, on the other side, could be explained by heterogeneity of migraine features, requiring further investigations for better understanding.

Our data also show that non-visual neurological symptoms, including HCD, during the aura in adolescent’s migraine, seem to be notable. Moreover, we previously clearly demonstrated the variability and complexity of aura symptoms [12]. Although the results do suggest certain sort of weak connection between complexity of the aura and interictal cognitive performance in migraineurs, further investigations are needed for comprehension of this relationship.

Cognitive performance decreases during migraine attacks, particularly the reading and processing speed, verbal memory and learning [26]. It is important to note that we only tested migraineurs who did not have migraine attack 1 week before or after testing. Therefore, our data cannot be inferred to episodic pain, although there is some evidence for interictal brain changes in migraineurs [27].

The main limitation of this study is that ACE-R test is not previously validated in adolescent population, but we find no reason that this fact should compromise the research, especially because ACE-R test, as a high-quality cognitive screening tool, fits our demands and is easily administered to the teenage population. For that reason, further similar studies are needed to corroborate our findings. The scarce sample size and the use of tertiary clinic patients could be possible limitations of this study.

Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination showed that migraineurs with aura got lower scores; moreover, patients with more complex aura showed a tendency toward worse outcome on ACE-R test. This study showed potential importance (role) of ACE-R test in brief clinical assessment of adolescents with migraine with aura in detecting mild interictal subclinical cognitive impairment. Also, ACE-R test could be beneficial for selecting the migraineurs with aura, who need a more thorough testing using batteries for assessing multiple neuropsychological functions. Future perspectives could be further evaluation of ACE-R test in larger sample size and the impact of migraine with aura on cognitive function in adolescents.

References

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (2013) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 386:743–800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4

Kernick D, Reinhold D, Campbell JL (2009) Impact of headache on young people in a school population. Br J Gen Pract 59:678–681. doi:10.3399/bjgp09X454142

Wöber-Bingöl C (2013) Epidemiology of migraine and headache in children and adolescents. Curr Pain Headache Rep 17:341. doi:10.1007/s11916-013-0341-z

Rasmussen BK, Olesen J (1992) Migraine with aura and migraine without aura: an epidemiological study. Cephalalgia 12:221–228

Hershey AD, Powers SW, Coffey CS, Eklund DD, Chamberlin LA, Korbee LL, CHAMP Study Group (2013) Childhood and Adolescent Migraine Prevention (CHAMP) study: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, comparative effectiveness study of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo in the prevention of childhood adolescent migraine. Headache 53:799–816. doi:10.1111/head.12105

Lampl C, Thomas H, Stovner LJ, Tassorelli C, Katsarava Z, Laínez JM, Lantéri-Minet M, Rastenyte D, Ruiz de la Torre E, Andrée C, Steiner TJ (2016) Interictal burden attributable to episodic headache: findings from the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 17:9. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0599-8

Moutran AR, Villa TR, Diaz LA, Noffs MH, Pinto MM, Gabbai AA, Carvalho Dde S (2011) Migraine and cognition in children: a controlled study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 69:192–195

Zgorzalewicz M, Mojs E (2006) Assessment of chosen cognitive functions in children and adolescents with primary headaches. Przegl Lek 63:24–28

Parisi P, Verrotti A, Paolino MC, Urbano A, Bernabucci M, Castaldo R, Villa MP (2010) Headache and cognitive profile in children: a cross-sectional controlled study. J Headache Pain 11:45–51. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0165-8

Riva D, Usilla A, Aggio F, Vago C, Treccani C, Bulgheroni S (2012) Attention in children and adolescents with headache. Headache 52:374–384. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.02033.x

Waldie KE, Hausmann M, Milne BJ, Poulton R (2002) Migraine and cognitive function. A life-course study. Neurology 59:904–908

Petrusic I, Pavlovski V, Vucinic D, Jancic J (2014) Features of migraine aura in teenagers. J Headache Pain 15:87. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-87

Schipper S, Riederer F, Sándor PS, Gantenbein AR (2012) Acute confusional migraine: our knowledge to date. Expert Rev Neurother 12:307–314. doi:10.1586/ern.12.4

Le Pira F, Zappalà G, Giuffrida S, Lo Bartolo ML, Reggio E, Morana R, Lanaia F (2000) Memory disturbances in migraine with and without aura: a strategy problem? Cephalalgia 20:475–478

Riva D, Aggio F, Vago C, Nichelli F, Andreucci E, Paruta N, D’Arrigo S, Pantaleoni C, Bulgheroni S (2006) Cognitive and behavioural effects of migraine in childhood and adolescence. Cephalalgia 26:596–603

Suhr J, Seng EK (2012) Neuropsychological functioning in migraine: clinical and research implications. Cephalalgia 32:39–54. doi:10.1177/0333102411430265

Mioshi E, Dawson K, Mitchell J, Arnold R, Hodges JR (2006) The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 21:1078–1085

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (2004) The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia 24:1–160

Bharti TT, Sandeep S, Lakhan K (2013) Cognitive function in schizophrenia and its association with socio-demographics factors. Ind Psychiatry J 22:47–53. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.123619

Mulder EJ, Linssen WH, Passchier J, Orlebeke JF, de Geus EJ (1999) Interictal and postictal cognitive changes in migraine. Cephalalgia 19:557–565

Wöber-Bingöl Ç, Wöber C, Uluduz D, Uygunoğlu U, Aslan TS, Kernmayer M, Zesch HE, Gerges NT, Wagner G, Siva A, Steiner TJ (2014) The global burden of headache in children and adolescents—developing a questionnaire and methodology for a global study. J Headache Pain 15:86. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-86

Koppen H, Palm-Meinders I, Kruit M, Lim V, Nugroho A, Westhof I, Terwindt G, van Buchem M, Ferrari M, Hommel B (2011) The impact of a migraine attack and its after-effects on perceptual organization, attention, and working memory. Cephalalgia 31:1419–1427. doi:10.1177/0333102411417900

Gaist D, Pedersen L, Madsen C, Tsiropoulos I, Bak S, Sindrup S, McGue M, Rasmussen BK, Christensen K (2005) Long-term effects of migraine on cognitive function: a population-based study of Danish twins. Neurology 64:600–607

Dzoljic E, Vlajinac H, Sipetic S, Marinkovic J, Grbatinic I, Kostic V (2014) A survey of female students with migraine: what is the influence of family history and lifestyle? Int J Neurosci 124:82–87. doi:10.3109/00207454.2013.823961

Rist PM, Kang JH, Buring JE, Glymour MM, Grodstein F, Kurth T (2012) Migraine and cognitive decline among women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 345:e5027. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5027

Gil-Gouveia R, Oliveira AG, Martins IP (2015) Cognitive dysfunction during migraine attacks: a study on migraine without aura. Cephalalgia 35:662–674. doi:10.1177/0333102414553823

May A (2009) Morphing voxels: the hype around structural imaging of headache patients. Brain 132:1419–1425. doi:10.1093/brain/awp116

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of Serbia (Project No. 41020 and No. 175015). Professor J. Jancic has received research Grant support from the Ministry of Education and Science, Republic of Serbia (Project No. 175031).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the child included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Petrusic, I., Pavlovski, V., Savkovic, Z. et al. Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination test for brief cognitive assessment of adolescents suffering from migraine with aura. Acta Neurol Belg 117, 97–102 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-016-0655-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-016-0655-9