Abstract

Conservation agriculture (CA)—the simultaneous application of minimum soil disturbance, crop residue retention, and crop diversification—is a key approach to address declining soil fertility and the adverse effects of climate change in southern Africa. Applying the three defining principles of CA alone, however, is often not enough, and complementary practices and enablers are required to make CA systems more functional for smallholder farmers in the short and longer term. Here, we review 11 complementary practices and enablers grouped under six topical areas to highlight their critical need for functional CA systems, namely: (1) appropriate nutrient management to increase productivity and biomass; (2) improved stress-tolerant varieties to overcome biotic and abiotic stresses; (3) judicious use of crop chemicals to surmount pest, diseases, and weed pressure; (4) enhanced groundcover with alternative organic resources or diversification with green manures and agroforestry; (5) increased efficiency of planting and mechanization to reduce labor, facilitate timely planting, and to provide farm power for seeding; and (6) an enabling political environment and more harmonized and innovative extension approaches to streamline and foster CA promotional efforts. We found that (1) all 11 complementary practices and enablers substantially enhance the functioning of CA systems and some (e.g., appropriate nutrient management) are critically needed to close yield gaps; (2) practices and enablers must be tailored to the local farmer contexts; and (3) CA systems should either be implemented in a sequential approach, or initially at a small scale and grow from there, in order to increase feasibility for smallholder farmers. This review provides a comprehensive overview of practices and enablers that are required to improve the productivity, profitability, and feasibility of CA systems. Addressing these in southern Africa is expected to stimulate the adoption of CA by smallholders, with positive outcomes for soil health and resilience to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Contents

-

1. Introduction

-

2. Supporting complementary practices

-

2.1.1 Mineral fertilizer

-

2.3 Crop chemicals

-

2.4.2 Agroforestry

-

2.5.1 Timely operations

-

2.5.2 Tools and machinery

-

2.6 An enabling institutional, social, and economic environment

-

3. Conclusion

-

Acknowledgments

-

References

1 Introduction

1.1 Food security in southern Africa

Global food production needs to increase (Ray et al. 2013) to keep pace with the ever-growing population (Godfray et al. 2010) and to counter increased impact of climate change (Wheeler and von Braun 2013). Agricultural productivity of two major food crops (maize and wheat) will be highly affected by biotic and abiotic stresses (Lobell et al. 2008) if no improved and adaptive measures are implemented, thereby highlighting the need for sustainable and productive agricultural systems (Fig. 1).

Average maize and wheat yield and expected worldwide demand for both crops. Yield-limiting and yield-reducing factors as projected are diseases, water/nutrient/energy scarcity, and climate change. Agronomy and breeding, on the other hand, will increase the average yield through better management. Source: CIMMYT using data from FAOSTAT (2013)

Social wellbeing and economic growth in southern Africa largely depend on agriculture (Blein and Bwalya 2013). The majority of farming systems in Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique are cereal-based mixed crop/livestock systems applied by smallholders with maize (Zea mays L.) as the dominant crop (Dowswell et al. 1996; Kassie et al. 2012; Dixon et al. 2001). Rainfall regimes in these areas vary from 500 to 1600 mm per annum. Other countries of southern Africa (e.g., Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa) are either too dry to sustainably grow maize or produce mainly in large-scale commercial farms. Livestock is an important component of the farming systems and consists mainly of cattle and goats, as well as chicken (Rufino et al. 2011; Rusinamhodzi et al. 2013). In large areas of southern Zimbabwe and Zambia, where crop production is marginal, cattle rearing is dominant, often in free-grazing arrangements (Zingore et al. 2007). The majority of farmers in southern Africa are smallholders who cultivate less than 5 ha. In Malawi for example, the average landholding size ranges between 0.2 and 3 ha (Ellis et al. 2003) while it is larger in Zambia and Zimbabwe, where cropping is more extensive (Gambiza and Nyama 2006; Aregheore 2009).

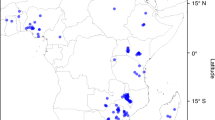

Multiple threats to productivity and sustainability are common throughout smallholder agricultural systems in southern Africa. The soils are often derived from granitic parent material and are thus sandy in texture (e.g., in Zimbabwe and Zambia) (Twomlow et al. 2006b). Most soils are low in inherent soil fertility and organic carbon (Fig. 2). They are acidic in some regions, leading to nutrient deficiencies (e.g., in northern Zambia). Many soils in southern Africa are also prone to erosion and other forms of degradation (Sanchez 2002; Sanginga and Woomer 2009).

The importance of timely planting, fertilization and weed control in conservation agriculture systems (left) and integration of agroforestry species (Faidherbia albida (Delile) A. Chev.) into conservation agriculture fields (right) to increase diversification, making use of leaf fall and gradually improving soil fertility, eastern Zambia

Cropping is only practiced during a single cropping season, which lasts from November to April, while the rest of the year is dry with very low and variable rainfalls (Whitbread et al. 2004). The unimodal rainfall season of short duration has consequences on and implications for the ability of smallholder farmers to grow crops and produce sufficient biomass for groundcover and feed (Mupangwa and Thierfelder 2014). Where livestock rearing is common, cropping systems are confronted with intensive crop/livestock interactions and major tradeoffs (Valbuena et al. 2012; Baudron et al. 2015a; Romney et al. 2003).

Southern Africa is heavily affected by climate variability and change (Masih et al. 2014), and projections suggest that the impact of climate change will be even more severe in the next decades (Cairns et al. 2013; Lobell et al. 2008). The most influential consequence of climate change will be: (a) the increase in temperature, leading to increased heat stress for crops; (b) change in rainfall patterns, resulting in more erratic rainfall events of high intensity, leading to floods in some areas and more frequent dry spells; (c) delayed onset of the rainy season; and (d) earlier tailing off of the cropping season (Cairns et al. 2012).

1.2 Rationale of conservation agriculture

The advent of the moldboard plow in Zambia and Zimbabwe in the 1920s, and the ridge-tillage systems in Malawi from the 1930s onwards, have progressively reduced the productivity and resilience of farming systems (Kumwenda et al. 1998), especially if ridges were established against the contour.

Conservation agriculture (CA) systems were identified in the 1980s and proposed as an alternative to tillage-based agriculture, first on commercial farms in Zimbabwe (Vowles 1989) and later on smallholder farmers’ fields (Wall et al. 2014; Oldrieve 1993). Conservation agriculture is based on three principles: (a) minimum soil disturbance, (b) crop residue retention through living or dead plant material, and (c) diversification through crop rotations and associations (Kassam et al. 2009; Hobbs 2007). In addition to these three core principles, there is a range of good agricultural practices and approaches needed to support short- and longer-term productivity and profitability of the system. There is general agreement that these good agriculture practices are essential for CA to function in the longer term (Vanlauwe et al. 2014; Sommer et al. 2014).

The performance of CA practices on agronomic productivity and economic profitability in southern Africa has been the focus of a series of studies in recent years and has been summarized by various scholars (Thierfelder et al. 2016a; Wall et al. 2014; Nyamangara et al. 2014b; Mafongoya et al. 2016; Brouder and Gomez-Macpherson 2014). The benefits of CA on soil moisture and infiltration have been investigated in long-term trials in Zambia and Zimbabwe (Thierfelder and Wall 2009). Effects of CA on soil biological activity were reported by Thierfelder and Wall (2010a), and changes in weed dynamics were highlighted by Muoni et al. (2014) and Mhlanga et al. (2015a). Contradicting results were found on carbon sequestration (Rusinamhodzi et al. 2011; Cheesman et al. 2016; Powlson et al. 2016). The three studies found that effects on soil carbon are dependent on the quality of CA implementation, such as the type of seeding system, the level of diversification, the type of rotation systems used, the amount of biomass that could be retained, and the inclusion of tree-based elements. Different CA systems often had site-specific responses, making it difficult to draw general conclusions (Nyamangara et al. 2013, 2014a; Thierfelder et al. 2016a; Mupangwa et al. 2016a; Thierfelder et al. 2015a, b; Baudron et al. 2012b). Most studies agree there are yield benefits in the medium to long term which are more pronounced in lower rainfall environments (Pittelkow et al. 2015; Thierfelder et al. 2014; Steward et al. 2018).

Variable results were also found on profitability of different CA cropping systems (Mazvimavi 2011; Mazvimavi and Twomlow 2009; Thierfelder et al. 2016a, b; Mupangwa et al. 2016a; Mafongoya et al. 2016; Baudron et al. 2015c). The economic performance of conservation agriculture systems is significantly affected by mechanization level (e.g., manual, animal traction, or tractor-drawn), the type of rotation or intercropping, the practices used as controls in the comparison, and other factors. Generally, it is difficult to assess the profitability of a farming system in cash-constrained environments where the opportunity cost for labor is low (unless it is in peak season, or farmers engage in growing high value crops such as tobacco). In southern Africa, farmers generally use family labor, which is often not costed, instead of hiring labor for land preparation or weed control (Andersson and D’Souza 2014; Baudron et al. 2012a). This makes an objective assessment of the economic performance of CA systems under smallholder farming situations difficult (Corbeels et al. 2014; Andersson and D’Souza 2014).

While there are several reported benefits of CA systems, a range of challenges and barriers to adoption have been discovered and summarized in recent reviews (Thierfelder et al. 2016b; Giller et al. 2015; Andersson and D’Souza 2014; Dougill et al. 2016; Glover et al. 2016). Among them are (a) limited knowledge and capacity of farmers to implement CA systems at a certain standard; (b) lack of sufficient biomass (e.g., crop residues) to retain on the soil surface in intensive crop/livestock systems (Valbuena et al. 2012); (c) lack of profitable rotation systems; (d) lack of access to critical CA inputs (e.g., specialized machinery, seed, fertilizer, and herbicides); (e) high costs of inputs (e.g., for specific seed, fertilizer, and herbicides); (f) cash constraints and lack of access to credit for initial investments; (g) lack of functional output markets for rotational crops; and (h) tradition and different prioritization by farmers. Many of these barriers are not unique to CA systems and are general constraints to smallholder farming in southern Africa.

Baudron et al. (2015c) proposed that, depending on site and farmer situation, the entry points for CA adoption in southern Africa would be in situations where: (a) there is limited availability of power for crop establishment and/or it is costly (this includes labor and draft power); (b) a delay in planting will lead to significant yield decline; (c) soil moisture limits or co-limits crop productivity; and/or (d) severe erosion and other forms of degradation affect short-term yields. Supported by better targeting to different farm typologies and the evidence from an ex-ante impact assessment, the adoptability and potential future adoption of CA could be enhanced.

1.3 Objectives of this study

While the three principles of CA have wide applicability on different rainfall and soil moisture regimes, soil types, and crops (Wall et al. 2014; Wall 2007), there is little understanding on how good agricultural practices and supporting enablers can improve the performance of CA systems under different circumstances. The objectives of this study are therefore to determine what the important enabling factors that improve the benefits of CA for smallholder farmers in southern Africa are and how do these enabling factors enhance the feasibility of CA implementation for such farmers?

The paper leaves out other practices that are either embedded in the CA system itself (e.g., legume rotation or intercropping) or are not practiced in southern Africa (e.g., the use of perennial cereals, flaming or solarization of weeds, etc.). We will describe commonly known supporting agricultural practices used in southern African agriculture and enabling factors, highlight their role and importance in various agro-ecologies and socio-economic environments, and discuss some of the challenges in the implementation of CA systems.

2 Supporting complementary practices

Good agricultural practices are not unique to CA cropping systems and improvements in agricultural practices have been sought throughout history. This review focuses on how these good agricultural practices enhance the functioning of CA systems specifically and what contributions they make to overcome limitations in the system.

Genetic gains in maize varieties adapted for southern Africa have been steady, with current potential maize grain yields (i.e., grown in unlimited water and nutrient situations with no loss due to weeds, pests, and diseases) above 10 tons ha−1 (Setimela et al. 2017; Masuka et al. 2016). However, yields obtained by smallholder farmers in the region are only a fraction of this and range between 0.5 and 2.5 t ha−1, with no increasing trend, for example, in Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Malawi (Ngwira et al. 2013; FAOSTAT 2017).

The difference between potential (expected under optimal conditions) and actual (reported by the farmer in field conditions) yields is referred to as the “yield gap” (Lobell et al. 2009; van Ittersum et al. 2013). Yield gaps are attributed to a combination of untimely and/or poor crop establishment; water, soil, and nutrient limitations; and other losses due to weeds, pests, and diseases (Tittonell and Giller 2013; Van Ittersum and Rabbinge 1997). The attainable yield refers to the maximum yield a farmer can achieve under rainfed conditions and is important to understand yield gaps.

The principles of CA and good agricultural practices may impact potential, attainable, and actual yields (Fig. 3) through synergistic effects. The figure illustrates how agricultural practices presented in this paper may complement CA principles in closing the yield gap (e.g., through improved seeds, soil, and water conservation) and/or support CA principles (e.g., through agroforestry species, fodder crops, and cover crops providing alternative biomass for residue cover) to obtain more ground cover, achieve greater carbon sequestration, or improve soil fertility.

The importance and contribution of good agriculture practices to the functioning of conservation agriculture, as displayed in a web of interactions with good agriculture practices. The green arrows show generally positive effects on the processes while red dotted arrows show negative effects. Black arrows show yield-limiting and yield-reducing factors. The overall effects are directed towards actual, attainable, and potential yields based on Van Ittersum and Rabbinge (1997)

Two approaches have been proposed in the past as to how CA systems could effectively be integrated into farming systems and how good agricultural practices could support this integration. One approach follows the logic of the so-called ladder approach (Sommer et al. 2013), originally developed by researchers working on integrated soil fertility management (ISFM). This theory assumes that different good agricultural practices are adopted by farmers in a sequential manner depending on their level of development and resource endowment (Vanlauwe et al. 2010, 2011; Sanginga and Woomer 2009). Indeed, sustainable intensification often hinges on farmers’ (physical and financial) access to inputs (fertilizers, herbicides, improved varieties), and their willingness to adopt these at a pace that they feel comfortable with in their own environment. Conservation agriculture principles and practices, including mechanization, could potentially feature at the higher end of this ladder and would be added one by one depending on the farmer’s ability to integrate those principles. Basic good agricultural practices, e.g., improved varieties, good fertilization (mineral and organic), and local adaptation would, therefore, have to be implemented first, gradually followed by the principles of CA (Sommer et al. 2013). The advantage of this approach would be that CA principles could be implemented in stages depending on the farmer’s ability. The disadvantage would be that incomplete CA systems (e.g., adoption of minimum tillage only) can lead to more negative effects (e.g., soil crusting or sealing) than gains (Giller et al. 2015; Baudron et al. 2012b), potentially discouraging farmers in the adoption process.

Other CA practitioners agree that basic good agricultural practices are necessary for the successful implementation of CA but propose an integration of all CA principles at once, starting from a small and manageable land area in the farm (e.g., 10% of the farm) where the CA systems can be expanded from (Thierfelder et al. 2013c; Wall 2007). The advantage of this strategy would be that the full benefits of CA could be reaped quickly, although the increased knowledge requirements to master the full CA system at once could hamper faster adoption (Giller et al. 2009). In addition, farmers may not be able to expand beyond plot level for some time using this approach.

This paper therefore aims at understanding how adequately supportive agricultural practices complement CA systems in their biophysical functioning and why they are needed under the conditions of southern Africa. We start with fertilizers and manures, followed by seed and plant population, before highlighting the importance of crop chemicals, alternative sources of mulch and diversification strategies, tools and machinery, and the importance of timely planting. We end the paper with a summary of enabling factors—both political and institutional—that are required to scale CA systems more effectively.

2.1 Appropriate nutrient management

2.1.1 Mineral fertilizer

The use of mineral fertilizers is a major component of modern agriculture and has been promoted since the theoretical background was provided by Justus Liebig and Carl Sprengel in the nineteenth century (van der Ploeg et al. 1999). In fact, there is widespread consensus that good and balanced nutrient supply is of vital importance to sustain any agricultural system. Adequate crop nutrition can be provided by mineral fertilizers, compost, or manure. Under nutrient-limited conditions in southern Africa, good fertilization, especially with nitrogen (Vanlauwe et al. 2011), is essential for CA systems to produce sufficient crop residues for surface mulching.

Crop residues that are commonly retained as soil cover in CA systems are mostly cereal derived, and thus have, unlike leguminous residues, a wide C/N ratio (Sakala et al. 2000; Gentile et al. 2009). A wider C/N ratio means that the organic resource contains a higher level of carbon units as compared with nitrogen units, which generally defines a lower-quality resource. A wider C/N ratio may lead to nitrogen immobilization (also called N lock-up) in the short term (Gentile et al. 2011), which calls for a different fertilization strategy under CA. This strategy may require a larger N dose or better fertilizer placement during crop establishment while less would be required at a later stage. The effect of N immobilization in maize has been tested with a Minolta Chlorophyll meter in southern Zimbabwe and shows that CA systems have an initially lower chlorophyll content (i.e., insufficient available N for the plant), which is later reverted, providing sufficient N for the plant (Baudron et al. 2015c).

Mineral fertilization in Africa has been promoted for decades, and although its benefits are widely known and acknowledged by farmers, its use has remained low (Fig. 4) (Morris 2007; Sommer et al. 2013), like many other technical innovations in Africa. In 2012, the average smallholder in Africa used only 17 kg ha−1 of mineral NPK fertilizer, the lowest rate on all continents, despite it being hailed as one of the most effective yield-enhancing technologies.

However, where CA systems performed well around the globe (e.g., in the Americas and Australia), it has often been associated with the need for high mechanization and good access to and use of mineral fertilizer (Bolliger et al. 2006; Kassam et al. 2009). This led to calls for building in a fourth principle, “appropriate use of fertilizer,” to improve the feasibility and functioning of CA systems (Vanlauwe et al. 2014), although others disagreed (Sommer et al. 2014).

The challenge for widespread mineral fertilizer use in CA systems in Africa is that smallholders are cash-constrained and struggle to acquire the necessary inputs at the onset of the planting season. Yet, this is only valid for farmers who are not recipients of a fertilizer support or subsidy program, such as the ones in Zambia or Malawi (Mhango and Dick 2011; Dorward and Chirwa 2011). Legumes in the rotation in CA systems are traditionally not fertilized, despite showing great response to phosphorous fertilization (Zingore et al. 2007; Waddington et al. 2007). Improving the access to phosphorous-based fertilizers could therefore help farmers reap additional benefits from legume rotations which could be measured through higher maize yields in cereal-legume rotations (Thierfelder and Wall 2010b).

Conservation agriculture systems may overcome the sole dependency on mineral fertilizers over time as diversification and residue retention will gradually improve soil nutrient stocks and crop productivity, allowing for a reduction in mineral fertilizer use in the long term. In summary, the use of sufficient nutrient supply is critical to generate enough biomass in CA systems and to overcome nutrient deficiencies.

2.1.2 Organic manures and compost

Organic manures and composts are traditional amendments (Ouédraogo et al. 2001) often used in combination with mineral fertilizers in smallholder farming systems, including CA (Ito et al. 2007; Rusinamhodzi et al. 2013). Because many smallholder farms in southern Africa are mixed crop-livestock systems (Murwira 1995; Valbuena et al. 2012), manure from cattle or other livestock that accumulates in the fields or in enclosures (locally called kraals: the South African word for fenced enclosure), provides an important source of organic fertilizer (Rusinamhodzi et al. 2013). For African smallholders, manure is a supplement to mineral fertilizer and an important source of nutrients (Bekunda et al. 2010), despite being variable in its quality (Lekasi et al. 2003; Harris 2002).

However, limited biomass regrowth and a long dry season set the limits for widespread use of manure in CA systems as cattle do not “produce” fertilizer but reallocate nutrients in the landscape. Approximately 1 ton (dry weight) of manure is produced every year by a fully grown head of cattle, which needs to be raised and fed with at least 1.8 t of biomass dry weight year−1 (Baudron et al. 2015b). Unless smallholder farmers have access to extensive grazing land, crop residues are not enough to feed such high amounts of biomass to cattle, even using the most efficient management.

Challenges with manure use in CA systems are that: (a) it is not plowed in with a moldboard plow as in conventional systems—it has to be applied either in basins or rip-lines and/or needs to be applied after direct seeding as basins and rip-lines do not incorporate the manure, which may lead to partial inefficiencies in the mobilization, access, uptake, and cycling of nutrients from manure (Powell et al. 2004; Rufino et al. 2006); (b) large quantities of nitrogen are excreted through urine and are lost through volatilization unless livestock are kept in kraals, which increases pH and P availability (Powell et al. 2004); (c) the N/P ratio of livestock manure is often different from the N/P requirement of plants leading to shortfalls in N and surplus in P (Powell et al. 2004). Manure handling and prevention of N loss are, therefore, important and often neglected interventions to improve the quality of manure and increase the efficiency of its use (Rufino et al. 2006).

Another organic resource available for use under CA and accessible for smallholders is compost, which is frequently produced by smallholders on a small scale and used for horticultural crops. However, with few exceptions, the amounts of nutrient-rich biomass with a narrow C/N ratio (e.g., from legumes) available for composting are usually small. This often limits the use of compost for field crops on a large scale, as compost making is very labor intensive. The most abundant organic materials available are cereal residues with a wide C/N ratio and low nitrogen content (Gentile et al. 2011), which often leads to minimal response by the crops if not enriched by animal manure, nitrogen, or leguminous residues.

In summary, organic manures and compost are a viable alternative to mineral fertilizer but availability and variability in their quality are major constraints to their widespread adoption by smallholder farmers in southern Africa.

2.2 Improved stress-tolerant varieties and plant population

2.2.1 Stress-tolerant varieties

Seed is a crucial agricultural input whose genetic potential determines the upper yield limit in crop performance and productivity (Cromwell 1990). Genetics determine the ability of varieties to resist both biotic and abiotic stresses (Almekinders and Louwaars 1999). Varieties with resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses are particularly relevant for CA systems. Through crop residue retention (which leads to a more humid micro-climate at the soil surface) a range of foliar diseases, enhanced by fungi and bacteria, become an important factor potentially affecting crop yields. The use of tolerant or resistant varieties provides the most effective and economical ways of controlling diseases, which can help control foliar diseases in CA systems (Thierfelder et al. 2015c). Resistant varieties are more durable, reduce crop losses and require limited use of chemicals (pesticides) that could negatively affect human health and the environment (Nelson et al. 2011).

Other stresses that affect crop production in southern Africa, where CA can make a positive impact, are abiotic stresses, which include drought, salinity, and poor soil fertility. For example, the 2015/2016 El Niño-induced drought was the most severe on record in eastern and southern Africa. The El Niño left many farmers food insecure as their major staple crop was affected by drought and the late onset of rains. This also severely affected the price of grain (FAO 2016; OCHA 2017). Improved stress-tolerant seed, when used in combination with CA, can mitigate yield loss and improve the resilience of agriculture systems (Arslan et al. 2014). In a study across 13 communities in Mozambique (Table 1), the response of different varieties (e.g., local variety without fertilizer, local variety with fertilizer, improved open pollinated varieties, and hybrids with fertilizer) was tested under two different cropping systems (conventional agriculture and CA). Variety response showed significant yield benefits to growing each type of variety under the different cropping systems. Yield gains of 330% or 3527 kg ha−1 were recorded between the local variety without fertilizer under conventional agriculture and the improved hybrid with fertilizer under CA.

Beside stress tolerance, breeders have also developed varieties that are more efficient in using nitrogen. These varieties can capture more N from the soil and utilize the absorbed N more efficiently (Good et al. 2004), thereby reducing the cost and application of N fertilizers (Rengel 2002). More N-efficient varieties can be beneficial in CA systems in which early season N-uptake is an issue.

In summary, the availability of stress-tolerant seed with various traits is essential for achieving high crop productivity and will help farmers in a wide range of environments and CA cropping systems to increase productivity, reduce risks of crop failure caused by pests and drought, and increase overall farm income. The combined use of drought-tolerant varieties with more “climate-smart” CA systems can lead to greater benefits under a changing climate than practicing each technology in isolation.

2.2.2 Plant stand and population

Plant stand and population are critical components in successful crop establishment and final yields of a crop. When CA systems are seeded with animal traction or tractor-powered seeding systems, the placement of the seed through mulch is critical and shows how effective and well-adapted a seeding system is to a specific CA system with crop residues, stubbles or living mulch in the field. The desired plant population is largely dependent on agro-ecology (e.g., rainfall, soil type) and the cropping systems used. Traditionally, farmers in Mozambique have been planting in crop spacings of 1 m × 1 m and planting bushels of five to eight seeds per hill (Diaz 2012, personal communication). The rationale is that farmers find it easier to weed in such fields with greater spacing at the expense of lower crop yields. One of the interventions by Sasakawa Global 2000 in Malawi and Mozambique was the introduction of row planting with a high population density of 75 cm between rows and 25 cm within row (Ito et al. 2007; Valencia et al. 2002). This intervention, implemented in combination with CA, was later referred to as the “Sasakawa spacing” which led to an increase in yield, especially in Malawi, and is now the dominant plant spacing countrywide (Ngwira et al. 2013). The use of improved plant spacing for any crop is, therefore, a key step towards enhancing yields for any given agro-ecology.

Planting spacing under CA can also be more advantageous for legume crops, such as in the example from Malawi, where farmers traditionally grow crops on annually dug ridges (Thierfelder et al. 2013b) with a fixed row spacing of 75 to 90 cm. Several leguminous crops (e.g., groundnuts and soybeans), however, achieve greater productivity under higher plant population. Under CA, crops are not planted in annual ridges but on the flat, allowing for more flexible row spacing. For groundnuts, the recommended row spacing has therefore been reduced to 37.5 cm, doubling the plant population (Bunderson et al. 2017). This increased yield (Table 2), reduced rosette disease, which is more common in conventionally ridged groundnuts, and gave more groundcover, thereby conserving more soil moisture and reducing erosion (Bunderson et al. 2017).

Increasing plant population also plays a significant role in controlling weeds using crop competition as a management practice (Mhlanga et al. 2016a). The use of a denser plant spacing encourages faster canopy cover and hence controls weeds more effectively (Teasdale 1995). This may also stimulate maize productivity, lead to greater yields (Anderson 2000), and is particularly important under CA, where initial weed control is critical as the soil is not plowed (Mhlanga et al. 2016a). In summary, adjustments to plant spacing are an efficient way to increase crop yields and offer additional benefits under CA when legume crops can be planted under more optimal plant spacings.

2.3 Crop chemicals

2.3.1 Pest and disease control under CA

The use of agricultural chemicals in crop production (e.g., foliar chemicals) and for crop protection (e.g., insecticides and fungicides) is sometimes inevitable to support CA systems. Their judicious use forms part of an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy (Ehler 2006). Crop chemicals may be needed in CA systems to control carry-over of pests in the residues, to manage specific pests attracted to no-tillage conditions, and to reduce foliar diseases.

Most cropping systems in the tropics and subtropics are invaded by phytophagous insects and disease-causing fungi and bacteria, and these need to be controlled if they exceed an economic threshold. Positive and negative (Knogge 1996) shifts in incidences of pest and disease attack, damage and effects on crop yields have been reported under CA (Howard et al. 2003; Gourdji et al. 2013). Hobbs et al. (2008), among other scholars, mentioned an increase in beneficial insects in south Asia such as large and predatory beetles, spiders, ants, wasps and earwigs under CA due to ground cover and reduced tillage, as the micro- and meso-environment can harbor those beneficial insects.

Decreased disease incidences due to breaking of disease cycles through rotations and antagonistic effect of a diverse microbial community on soil pathogens have also been reported by Hobbs et al. (2008) and Mupangwa (2009). However, as mentioned above, studies also reported the increase in foliar diseases in cereals under reduced or no-tillage and residue retention (Bailey 1996) as well as emergence of new pathogens (Howard et al. 2003).

This suggests that the implementation of CA principles alone is not sufficient for the control of pests and diseases, and this calls for an IPM approach, which includes the combined use of resistant varieties, judicious use of agrochemicals, biological control methods, and agronomic practices (Ehler 2006; Owenya et al. 2011).

Increasing environmental concerns and bans on some of the chemical products have facilitated research on biological control of pest through intercropping, hedgerows, and push-pull systems (Hassanali et al. 2008; Cook et al. 2007), which are very compatible with CA systems and often cheaper than chemicals. By nature, CA systems foster biodiversity that may lead to increases in pests but also the proliferation of natural enemies of pests (Jaipal et al. 2002) that potentially lead to increased biocontrol (Chenu et al. 2011). However, there are also risks that pupae of specific pests can multiply more rapidly in soils that are not tilled (Jobbágy and Jackson 2000) or are attracted by abundant decaying organic material, such as in the case of the white grub (larvae of Phyllophaga ssp. and Heteronychus spp.), which has been highlighted as a potential pest under CA (Thierfelder et al. 2015c). Biological control is slow, and depends largely on the populations of both predators and the pests, which may be too imbalanced to suppress pest populations (Howard et al. 2003). In crisis situations, the use of crop chemicals is often inevitable to control pests and diseases.

In seasons of excessive rainfall, some soils under CA are prone to waterlogging (Thierfelder and Wall 2009). Due to excessive moisture, the proliferation of diseases increases (Linn and Doran 1984). In such conditions, most legumes that are integrated in CA systems for diversification of plant associations suffer fungal attacks, thus requiring the use of fungicides to control disease. Furthermore, legumes (e.g., cowpeas) are more frequently attacked by leaf eaters and aphids; hence, it may be important to spray insecticides to control them (Jackai and Adalla 1997).

In summary, and in the absence of alternative ecological control measures practiced in more holistic farming systems, crop chemicals form a necessary part of crop protection in all farming systems, including CA. However, these have to be used with great caution as misuse may result in harm to crops, livestock, humans, and other untargeted faunal species (Bussière and Cellier 1994). Attention needs to be placed on the correct timing and dosage, as well as the mode of action for effective pest control and spraying of chemicals, which requires significant training and support by the extension services available to farmers.

2.3.2 Weed management and their control

Weed management is an essential agronomic practice as weeds can lead to crop yield reductions of up to 90% (Nair et al. 2009). Shifting to CA is associated with changes in the microenvironment, which in turn affects the spectrum of weeds that will emerge (Grant et al. 1989). Weed biomass and spectrum are mostly affected by soil fertility and fertilization, although mulching under CA can also suppress weeds (Mtambanengwe et al. 2015). However, providing a range of organic amendments of different qualities may also reduce the competition between crops and weeds through “niche differentiation” (Radosevich et al. 1997). The uncertainties associated with weed dynamics in CA systems highlights the need for more research on weed control in southern Africa (Lee and Thierfelder 2017).

In southern Africa, weed management is mainly based on the use of the hand hoe (Vogel 1994), and, although widely used, it is labor intensive (Muoni et al. 2013), places greater burdens on women and youth, and is often untimely implemented (Thierfelder et al. 2015c). Alternatively, the integration of green manure cover crops (GMCCs) either as rotational or relay crops has been reported to be effective in weed control, although an understanding of the mechanisms by which they suppress weeds is necessary (Mhlanga et al. 2016b, a). In southern Africa, the use of GMCCs in weed control is limited by land holding size, availability of GMCC seeds and their markets, and available soil moisture to grow the crops, among other reasons (Thierfelder et al. 2013a).

An integrated weed management program under CA can be effective and the use of herbicides is viewed as an important component of it, despite the efforts by many organizations to reduce their use (Swanton and Murphy 1996). When used properly, herbicides are the most effective way of controlling weeds as compared with other methods (Chhokar et al. 2007; Muoni et al. 2013, 2014). Herbicides have different modes of action in controlling weeds (e.g., contact, systemic, soil sterilizing) and may be either selective or non-selective. An understanding of herbicides is essential for their successful application to ultimately lead to a reduction in weed populations under CA. For example, the application of a contact herbicide is not as effective when controlling weeds that propagate through rhizomes with a stoloniferous growth habit, such as couch grass (Cynodon dactylon L), since contact between herbicide and underground rhizomes is limited (Varshney et al. 2012).

Herbicide use in CA systems of southern Africa has become more frequent (Ito et al. 2007), although access to herbicides and information on how to use them remains a challenge (Muoni et al. 2013). If farmers use herbicides in southern Africa, they often apply glyphosate [N-(phosphono-methyl) glycine] as a weed post-emergent application to kill off all weeds at the beginning of the season (Ngwira et al. 2013). This practice is effective but there are suggestions that this should be coupled with the use of selective herbicides as post-emergent applications to achieve an all-season weed-free environment. Muoni et al. (2013) have shown that simultaneous mixing of several herbicides in a knapsack sprayer with different modes of action and selectivity is more effective and economic in controlling weeds as compared to using individual herbicides and hand hoe weeding alone.

In Malawi, the use of herbicides was an important entry point for farmers to adopt CA (Ngwira et al. 2013, b; Thierfelder et al. 2013b). However, herbicides only address a critical need to reduce farm labor by women and children and are not a prerequisite for successful application of CA on smallholder farmers’ fields. Studies in Malawi, for example, showed that herbicide-assisted weed control had equally high yields than plots without herbicides as long as the manual weed control was done in a timely manner (Nyagumbo et al. 2016). Other observations from Malawi showed a reduction in the parasitic weed striga (Striga asiatica (L.) Kuntze) on CA fields, which was partially due to an increase in soil fertility and complete control by herbicides. The decrease in weed pressure has been shown on trials in Zimbabwe where weed pressure was reduced over a period of four cropping seasons (Muoni et al. 2014).

In summary, judicious use of herbicides can support farmers in the initial stages of conversion from conventional systems to CA. However, it is important that farmers receive adequate training on safe use and handling of these products. Once weed pressure decreases, the use of herbicides can be scaled down (Mhlanga et al. 2015a; Skora Neto 1993).

2.4 Increased groundcover and diversification

2.4.1 Groundcover with alternative material

Soil cover is critical for CA (Thierfelder and Wall 2009) although the amount of biomass that farmers can retain is often limiting. No-tillage without soil cover can be more detrimental in some circumstances than the traditional practice as this may lead to soil crusting and sealing; the more the soil can be covered, the better the performance of CA will be in the longer term (Govaerts et al. 2005). Cereal residues, left on the field after harvesting or applied at the beginning of the cropping season after temporary removal, are the predominant source of soil cover for CA systems practiced in southern Africa (Thierfelder et al. 2015b). However, challenges of free grazing during the dry season, low biomass production in the cropping systems, and the multi-purpose use of crop residues on smallholder farms, lead to the scarcity of residues in southern Africa for all desired uses with significant trade-offs involved (Duncan et al. 2013; Mupangwa and Thierfelder 2014; Valbuena et al. 2012).

Alternative mulching strategies are critical for the future of smallholder CA systems in order to derive the full benefits of the three pillars of CA. However, intensifying livestock production and closing the maize yield gap, as suggested by Baudron et al. (2014), can also reduce the amount of fodder needed and increase the overall available biomass, thus enabling more retention of generally lower-quality cereal residues on the soil surface. Residues of other plant species found in the forests, on contour strips or rangeland around smallholder farms can also be utilized as soil cover, although the labor burden to import residues makes it an unattractive option to some farmers. Smallholders in southern Africa apply residues of different grass species, litter (mixture of leaves and twigs) from the indigenous trees, and litter from fruit trees planted around homesteads (Nyamangara et al. 2009; Nyathi and Campbell 1993; Mtambanengwe and Kirchmann 1995; Musvoto et al. 2000). Litter derived from Uapaca kirkiana (Benth), Brachystegia spiciformis (Benth), and Julbernardia globiflora (Benth) trees, and thatching grass (Hyparrhenia filipendula (Hochst (Stapf)) are commonly used by smallholders for soil fertility restoration and mulching in southern Africa (Nyathi and Campbell 1993; Mupangwa et al. 2016b). Fully mature thatching grass is often not completely grazed by livestock because of its high lignin content, making it available for other purposes, including construction and mulching on the farm. Residues can also be availed from leguminous species, such as pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.), sunnhemp (Crotalaria juncea L.), common rattlepod (Crotalaria grahamiana L.), and fish bean (Tephrosia vogelii L.), whose stover can be slashed and left on the soil surface after they have senesced (Sakala et al. 2000; Nyamangara and Nyagumbo 2010; Mupangwa et al. 2016b).

Alternatively, living mulches derived from herbaceous and non-herbaceous cover crop species, relay intercropped into cereal-dominated cropping systems, are a promising solution for CA systems in southern Africa (Mupangwa and Thierfelder 2014; Mhlanga et al. 2016b). Common herbaceous cover crop species adapted to southern Africa include velvet bean (Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC.), lablab (Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet) and jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC.), all of which provide soil cover during the cropping period and beyond (Waddington 2003; Mhlanga et al. 2015b; Odhiambo et al. 2010).

2.4.2 Agroforestry

Conservation agriculture cropping systems benefit from the addition of tree-based elements, which support the system’s functioning, diversification, and resilience (Garrity et al. 2010; Mutua et al. 2014). Residue retention, one of the key principles of CA, can be improved by trees and shrubs which provide additional biomass for surface retention. In addition, the nutrient status of field crops can be enhanced through trees in the landscape (Baudron et al. 2017). The same applies for the principle of crop diversification as trees provide a more variable and diverse habitat. A range of tree species have been shown to integrate well into CA farming systems (ICRAF 2009). These systems have been promoted under the umbrella of evergreen agriculture as well as a system labeled as “CA with trees” (Lahmar et al. 2012; Garrity et al. 2010; ICRAF 2009). Here, the supporting elements are leaves, shade and additional groundcover from tree prunings that can overcome the shortcomings of CA systems based on maize residue retention alone.

Two species have been tried extensively by various organizations. The integration of the winterthorn tree (Faidherbia albida Delile A. Chev.) is seen as a successful example on how both crops and trees can coexist. Faidherbia trees have a reverse phenology and shed their leaves during the cropping season while they have their full canopy during the dry winter season. Systematic integration of Faidherbia into CA farming systems shows that cereal yields can be enhanced while mineral fertilizer rates can be reduced (Bunderson et al. 2002; Garrity et al. 2010). The deep rooting trees start to benefit the soils after 9–10 years and recycle nutrients from deeper layers to the soil surface. However, the reverse phenology only happens when trees have access to groundwater and when they are not pruned excessively. This may lead to competition between trees and crops for some years. An investment into planting trees requires secure land-use rights and tenure systems as otherwise, this investment will not be attractive to farmers.

Another good example of integration of agroforestry species is the use of Gliricidia (Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp.) in CA systems in eastern Zambia (Lewis et al. 2011). There Gliricidia is planted in rows 5 m apart with a close in-row spacing (about 1 m), and the trees are pruned every year to make use of the nutrients in the leaves (Lewis et al. 2011). This provides the necessary soil fertility, ground cover and supports cattle feeding. Like Faidherbia, Gliricidia is a leguminous tree and its leaves are rich in N content (Mafongoya et al. 2011). Maize or groundnuts that can be planted in the 5 m inter-row space and will benefit from the pruned leaves to an extent that NPK fertilizer can be reduced.

In the last decade, there has been renewed interest in southern Africa to invest in these greener technologies given the high price of mineral fertilizer and/or lack of access to it. However, critical lessons have to be learned from West Africa where alley cropping was promoted for more than 40 years (Kang et al. 1990; Sanchez 1995) with documented increases in productivity and profitability (Buresh and Tian 1997; Ehui et al. 1990) but disappointingly low adoption rates of the technology (Adesina 1999). Constraints identified were insecure property rights (over land and trees), increased labor demands, a long lag time between the establishment and the accrual of benefits, competition for production resources (light, water, and nutrients) above- and below ground, and difficulties to adapt some of the species (trees and shrubs) with food crops (Atta-Krah and Sumberg 1988; Carter 1995; Sanchez and Hailu 1996).

In summary, CA systems can significantly benefit from the biomass contributions of tree-based components. Yet, agroforestry systems are more likely to be adopted in situations of high soil fertility decline, with erosion problems, and where fuelwood and fodder are scarce and in high demand (Adesina 1999).

2.5 Increased efficiency of planting and mechanization

2.5.1 Timely operations

The use of modern CA seeding systems and technologies often allows for timely planting as the land does not have to be plowed beforehand. In addition, the weak condition of draft animals at the onset of the cropping season after a long dry season with inadequate feeding results in more difficult and time-consuming primary land preparation with a moldboard plow until the soil has been softened by the rains and/or the animals have gained some strength. The limited availability of draft animals also means that non-draft power owners have to wait to rent oxen from their neighbors. This results in farmers delaying planting until the draft animal owners have finished their own fields.

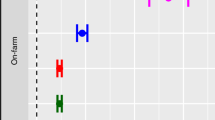

Yield losses in maize of circa 5% week−1 of delayed planting have been reported from Zimbabwe (Elliott 1989). In other studies at Mangwende Communal Lands of Zimbabwe, delayed planting for more than 21 days reduced maize grain yields by 32% (Shumba et al. 1989). Ox-drawn ripping systems combined with herbicides were found to be more effective in enabling timely planting in Mangwende, which resulted in increased grain yields on 13 out of 18 sites compared with the conventional farmer practices (Shumba et al. 1992). It is clear from the aforementioned results that the time of planting makes a significant contribution to ultimate yields under rainfed conditions. Similar results were also reported from a semi-arid region of Zimbabwe (Fig. 5), where simulated maize yields showed the highest yield reductions due to delayed planting in fertilized maize treatments (Mugabe and Banga 2001).

Simulated maize grain yields (using the CERES crop simulation model) under different fertilizer regimes in response to delays in planting date, Romwe, Zimbabwe, Nov 1995–Feb 1996. Adapted from Mugabe and Banga (2001)

A more recent analysis of planting dates, based on available household labor data, shows that animal traction-based CA and winter-prepared CA basins enabled farmers to plant earlier (Nyagumbo et al. 2017). CA is therefore a very useful intervention for farmers whose farm power is constrained for land preparation. The reduced labor needed for seeding with a ripper or direct seeder helps these farmers to be more labor efficient during seeding and effectively make use of the narrow planting window. In addition, for those farmers who do not own cattle, it is also more beneficial to prepare basins during the dry winter season and reap the full benefits of a complete cropping season once the first effective rains occur.

The aim in CA systems is therefore to: (a) disaggregate labor peaks for planting from the onset of the rain or (b) to use implements that allow for fast seeding after the first rains. The planting basins system as recommended in Zimbabwe by Oldrieve (ZCATF 2009) and in Zambia (Aagaard 2011) follows this logic as they enable planting with the first rains, thereby making full use of the cropping season. The second strategy is planting with direct seeding or rip-line seeding systems that require less labor at the onset of the rainy season, which allows for faster crop establishment (Nyagumbo et al. 2017). However, basin-based CA systems have had major setbacks in both countries as the adoption has been considered more “labor intensive” by smallholders while animal traction CA systems have started to increase (Arslan et al. 2014; Grabowski et al. 2014a, b; Umar 2014). In summary, timely planting is critical for successful implementation of CA cropping systems as yields are directly affected by delays in planting.

2.5.2 Tools and machinery

Manual CA systems—using a planting stick (dibble stick) or planting hoes (Sims et al. 2012)—have been adopted by many smallholders in Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, but often on small areas due to labor constraints (Mazvimavi et al. 2009; Ngwira et al. 2014a). As a result, there has been a major push to introduce new tools on smallholder farms to increase productivity and reduce farm labor throughout the last two decades, (Sims et al. 2012). This started with the introduction of hand planter systems such as jab planters, but increasingly with animal traction planting and seeding equipment such as the Magoye ripper, the Palabana subsoiler, and animal traction direct seeders (Sims et al. 2012). With these interventions, the primary interest was to modify existing tools at minimal cost to plant under no-tillage conditions, increasing labor productivity while reducing soil disturbance. Increased maize productivity has been measured with animal traction CA equipment and documented in Zimbabwe and Zambia (Mupangwa et al. 2016a; Thierfelder et al. 2015b). This is particularly evident with the ripper tine attachments that can easily be fitted onto a traditional plow beam while requiring only a moderate investment of approximately US$25 per attachment. Ripper attachments can also be made out of scrap metal by a local artisan making its access more feasible. Other animal traction direct seeders from Brazil have been successfully tested by researchers in the region (Thierfelder et al. 2015b), but their widespread uptake has been limited by low demand of smallholders, lack of local manufacturing and credit, and economic crises that periodically hit southern African economies.

Draft animals to pull animal traction equipment, tend to be concentrated in few areas, e.g., where cattle diseases are rare (Sims and Kienzle 2006) and animals find enough fodder to survive the winter season. In many parts of southern Africa, diseases such as trypanosomiasis and tick-borne diseases (e.g., Theileriosis East Cost Fever) limit the number of draft animals. Even in areas where draught animals are common, their numbers are in decline because of increased feed shortages, especially during the dry winter season and droughts, and/or due to emerging diseases (Mrema et al. 2008). Thus, many farmers require additional available power sources.

Throughout the last 5–10 years, a quiet revolution on smallholder mechanization has started to emerge in southern Africa (Baudron et al. 2015b). Unlike interventions of the 1950s and 1960s, where large tractor schemes with unviable business models and undesirable consequences on farm labor and the environment were run by African governments, the drive has gone towards more “appropriate-scale” mechanization. Based on the precondition that great impediments to practice CA are lack of farm power, labor constraints, and water limited situations (Baudron et al. 2015c), the introduction of small two-wheel tractors with associated equipment has started to happen (Baudron et al. 2015b). In summary, more efficient seeding systems powered by two-wheel tractors will allow farmers to practice CA on a larger scale without being limited by manual labor or animal traction. Labor saving technologies, as offered by animal traction seeding systems and/or two-wheel tractors can address labor shortages and critical draft power needs in farming communities.

2.6 An enabling institutional, social, and economic environment

Unlike Latin America, where no-tillage planting systems were developed by farmers and extended through farmer organizations (Bolliger et al. 2006), CA promotion in southern Africa was mostly driven by research and development organizations and farmers’ unions (Twomlow et al. 2006a; Mashingaidze et al. 2006; ZIMCAN 2012). A positive and enabling institutional environment has played a key role in southern Africa to mainstream CA in the political development agenda although it should be highlighted that the implementation of favorable policies has been limited due to weaknesses and financial constraints in local governments, thereby hampering the process. Zambia, for example, issued a supporting policy in 1999 (Haggblade and Tembo 2003; Baudron et al. 2007). Zimbabwe formed the first CA task force in 2003 and developed an investment framework in 2011/2012 (AMID 2012) which developed CA guidelines (ZIMCAN 2012; ZCATF 2009). Many countries in southern Africa followed with their own formation of national CA task forces (e.g., Mozambique, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, and Tanzania, among others). Malawi officially released CA as an “approved technology” in 2013 (Ligowe et al. 2013) and consequently, the development of comprehensive guidelines for CA implementation followed (NCATF 2016). All these have supported the wider discussion about CA systems and its diffusion, although its strong political backing has also been looked at more critically in recent years as they did not translate into widespread uptake (Dougill et al. 2016; Whitfield et al. 2015).

Lack of functional input and output markets for various crops and machinery has been highlighted as an impediment to the widespread adoption of rotational crops, increased diversification and mechanization (Thierfelder et al. 2013a). However, this is not unique to CA and requires a more holistic approach to sustainable agricultural intensification at the government level, which has recently been formulated for Zambia (Arslan et al. 2017). Furthermore, the lack of directives against “free hand-outs” by different institutions and their often untimely distribution have been found to contribute to poor productivity in rainfed systems in Zimbabwe (Nyagumbo and Rurinda 2012).

Uncoordinated extension with contradicting extension messages could be one of the reasons why CA uptake in the region has been (s)low (Bunderson et al. 2017). Indeed, the drive for change and enthusiasm by an extension officer plays a critical role in behavior change among smallholder farmers. This requires strong capacity building of existing extension services to promote the principles and practices of CA. Furthermore, it has become clear in the promotion of more complex technologies, such as CA, that there is need for a different extension approach as compared with the linear extension of a component technology, such as fertilizer or seed (Thierfelder and Wall 2011; Ekboir 2002). In addition, CA systems require a change in the way crops are seeded, knowledge about residue retention, weed control, different crop varieties, machinery, and harvesting procedures. These are critical for the success of CA cropping systems and need to be acquired by the farmer, which often requires a different and more participatory way of extension to enable widespread adoption.

New ways of extension have been explored in innovation systems or platforms (Misiko 2017) where multiple players jointly work on adapting CA systems to the needs and environmental circumstances of the smallholder farmer. Innovation systems are therefore recommended as one way to achieve more sustained and widespread adoption of CA (Thierfelder and Wall 2011). Experience from Latin America and Southeast Asia have confirmed that the participatory interaction of players in the innovation process are critical to achieve buy-in and adaptation (Spielman et al. 2009; Ekboir 2002; Erenstein et al. 2012). Another successful extension approach is the lead-farmer extension model, which has also been tried and tested and led to significant adoption of CA systems in Zambia and Malawi (Bunderson et al. 2017; Corbeels et al. 2014). Scaling through mother and baby trials, market led approaches, contract farming arrangements, farmer field schools, farmer to farmer exchange, and demonstration and field day approaches have recently been tried by various organizations to boost adoption with variable success (Sustainet 2010; Lewis et al. 2011; Mafongoya et al. 2016). However, overall adoption of CA is still much lower in southern Africa than in other regions of the world (Kassam et al. 2015) which will require more research on selecting the best diffusion mechanism and scaling approaches.

Better targeting, recommendation domains and ex ante analysis are important new tools and assessments to match CA technologies with the needs of smallholders in southern Africa (best-fit), which operate in diverse and complex environments (Tittonell et al. 2012). This also supports previous conclusions that CA systems have to be tailored to farmers’ sites and circumstances (Knowler and Bradshaw 2007; Thierfelder et al. 2016a).

3 Conclusion

CA systems in southern Africa have been researched extensively during the last three decades, and a considerable body of knowledge has been summarized in recent years. The three general principles are considered not sufficient to have functional CA systems under the prevailing conditions of southern Africa, as other supporting and complementary practices and enabling factors are required. This study sought to identify important enabling factors that improve the benefit of CA for smallholder farmers in southern Africa and to define how these enabling factors enhance the feasibility of CA systems for such farmers. We studied these factors and summarized their beneficial effects and challenges (Table 3).

We find that CA systems require adequate fertilization which can be achieved through mineral fertilizer, integration of legumes, manure, or compost. However, while CA demonstration and trial plots have often received adequate nutrient supply, smallholder farmers often lack the capacity to buy sufficient amounts of mineral fertilizers and are therefore more dependent on alternative resources and diversification strategies.

Improved stress-tolerant varieties can support farmers practicing CA to address major crop diseases, pests, low N, and drought, while offereing high yields. Combinations of improved varieties with CA and other supporting practices lead to incremental benefits. Row spacings under CA and new opportunities to plant crops on flat fields allow farmers to optimize crop yields and address specific plant population needs by leguminous crops.

Despite environmental concerns, successful implementation of CA systems may require the use of some crop chemicals to counter pests and diseases as part of an IPM approach. However, judicious use of pesticides should be stressed to avoid negative side effects on the environment. As plowing for weed control is abandoned under CA, there is an additional need for an integrated weed control strategy. Weed control under CA can be achieved through various cultural practices (e.g., manual weeding, rotation/intercropping with competitive species, and residue retention, among others). Chemical solutions with herbicides could potentially be another option for labor-constrained smallholders, although their use requires access, additional cash, and information on how to use different products.

Residue retention and sufficient groundcover are required to reap the full benefits of CA systems over time. In cereal-based mixed crop livestock systems, this can be a great challenge as residues and other organic resources are in short supply. Alternatives, such as leaf litter from trees, grass, green manure cover crops, and even cuttings from agroforestry species, can be used to enhance the level of biomass. Yet, all resources used from other places require additional labor and may lead to undesirable nutrient flows within the landscape, which may cause increased degradation in some areas.

CA in southern Africa has mostly been promoted on a small scale, leading to adoption of this system on only parts of the farms. The introduction of appropriately scaled mechanization through animal traction equipment as well as small motorized options can overcome this bottleneck while addressing the urgently-needed increase in farm power. Disaggregation of labor peaks through early preparation of basins or rip-lines or faster establishment of crops through animal traction and motorized solutions may support timely operations and allow for utilization of a longer cropping season, which leads to greater yields.

An enabling political environment, appropriate extension, and innovation in CA systems are essential for providing support in the promotion, dissemination of primary sources of information, and adaptation of this relatively new cropping system to southern African conditions. A more coordinated extension program and updated trainings of extension services may, however, be required in the future.

There is yet no clarity if a sequential implementation of CA systems via a “ladder approach” would be more feasible to farmers or an “all in one” approach, starting from a small scale and growing from there to larger scales. Both approaches seem to have their merits and limitations and should be more carefully explored.

In summary, supporting good agricultural practices and enablers are critical for making CA cropping systems more feasible to smallholders in southern Africa. The integration of supportive agricultural practices with CA cropping systems should lead to narrowing the yield gap, which would define how successful the application is. However, each of those supportive agricultural practices has its own benefits and challenges when farmers start applying them (Table 3; Fig. 3). As CA is a very flexible system spanning from manual planting with a stick to tractor-drawn direct seeding, from maize intercropping to very sophisticated rotation systems, it is a mandatory requirement that CA systems are adapted to the site and farmer conditions.

References

Aagaard P (2011) The practice of conventional and conservation agriculture in east and southern Africa, vol 1. Conservation Farming Unit Zambia, Lusaka

Adesina A (1999) Policy shifts and adoption of alley farming in West and central Africa. IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria

Almekinders CJ, Louwaars NP (1999) Farmers’ seed production: new approaches and practices. Intermediate Technology, London

AMID (2012) Conservation agriculture framework for Zimbabwe Printaid, Harare, Zimbabwe

Anderson RL (2000) Cultural systems to aid weed management in semiarid corn (Zea mays). Weed Technol 14(3):630–634. https://doi.org/10.1614/0890-037X(2000)014[0630:CSTAWM]2.0.CO;2

Andersson JA, D’Souza S (2014) From adoption claims to understanding farmers and contexts: a literature review of conservation agriculture (CA) adoption among smallholder farmers in southern Africa. Agric Ecosyst Environ 187:116–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.08.008

Aregheore EM (2009) Country pasture/forage resource profiles: Zambia. FAO, Rome, Italy

Arslan A, Cavatassi R, Alfani F, Mccarthy N, Lipper L, Kokwe M (2017) Diversification under climate variability as part of a CSA strategy in rural Zambia. J Dev Stud:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1293813

Arslan A, McCarthy N, Lipper L, Asfaw S, Cattaneo A (2014) Adoption and intensity of adoption of conservation farming practices in Zambia. Agric Ecosyst Environ 187:72–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.08.017

Atta-Krah A, Sumberg J (1988) Studies with Gliricidia sepium for crop/livestock production systems in West Africa. Agrofor Syst 6(1–3):97–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02220111

Bailey K (1996) Diseases under conservation tillage systems. Can J Plant Sci 76(4):635–639. https://doi.org/10.4141/cjps96-113

Baudron F, Andersson JA, Corbeels M, Giller KE (2012a) Failing to yield? Ploughs, conservation agriculture and the problem of agricultural intensification: an example from the Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe. J Dev Stud 48(3):383–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2011.587509

Baudron F, Delmotte S, Corbeels M, Herrera JM, Tittonell P (2015a) Multi-scale trade-off analysis of cereal residue use for livestock feeding vs. soil mulching in the Mid-Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe. Agric Syst 134:97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2014.03.002

Baudron F, Duriaux Chavarría J-Y, Remans R, Yang K, Sunderland T (2017) Indirect contributions of forests to dietary diversity in Southern Ethiopia. Ecol Soc 22(2):28. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09267-220228

Baudron F, Jaleta M, Okitoi O, Tegegn A (2014) Conservation agriculture in African mixed crop-livestock systems: expanding the niche. Agric Ecosyst Environ 187:171–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.08.020

Baudron F, Mwanza H, Triomphe B, Bwalya M (2007) Conservation agriculture in Zambia: a case study of southern province. Conservation Agriculture in Africa Series. African Conservation Tillage Network, Centre de Coopération Internationale de Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Nairobi, Montpellier, Rome

Baudron F, Sims B, Justice S, Kahan DG, Rose R, Mkomwa S, Kaumbutho P, Sariah J, Nazare R, Moges G (2015b) Re-examining appropriate mechanization in Eastern and Southern Africa: two-wheel tractors, conservation agriculture, and private sector involvement. Food Security 7(4):889–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0476-3

Baudron F, Thierfelder C, Nyagumbo I, Gérard B (2015c) Where to target conservation agriculture for African smallholders? How to overcome challenges associated with its implementation? Experience from eastern and southern Africa. Environment 2(3):338–357. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments2030338

Baudron F, Tittonell P, Corbeels M, Letourmy P, Giller KE (2012b) Comparative performance of conservation agriculture and current smallholder farming practices in semi-arid Zimbabwe. Field Crop Res 132:117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2011.09.008

Bekunda M, Sanginga N, Woomer PL (2010) Chapter four—restoring soil fertility in sub-Sahara Africa. In: Donald LS (ed) Advances in agronomy, vol 108. Academic Press, pp 183–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2113(10)08004-1

Blein R, Bwalya M (2013) Agriculture in Africa: transformation and outlook. NEPAD Transforming Africa, pp. 14–15

Bolliger A, Magid J, Amado TJC, Scora Neto F, Dos Santos Ribeiro MDF, Calegari A, Ralisch R, De Neergaard A (2006) Taking stock of the Brazilian “zero-till revolution”: a review of landmark research an farmers' practice. Adv Agron 91:47–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(06)91002-5

Brouder SM, Gomez-Macpherson H (2014) The impact of conservation agriculture on smallholder agricultural yields: a scoping review of the evidence. Agric Ecosyst Environ 187:11–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.08.010

Bunderson WT, Jere ZD, Hayes IM, Phombeya HSK (2002) Land care practices in Malawi. Malawi Agroforestry Extension Project Publication No. 42. Total LandCare, Lilongwe, Malawi

Bunderson WT, Jere ZD, Thierfelder C, Gama M, Mwale BM, Ng’oma SWD, Museka R, Paul JM, Mbale B, Mkandawire O, Tembo P (2017) Implementing the principles of conservation agriculture in Malawi: crop yields and factors affecting adoption. In: Kassam A, Mkomwa S, Friedrich T (eds) Conservation agriculture for Africa: building resilient farming systems in a changing climate. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK

Buresh R, Tian G (1997) Soil improvement by trees in sub-Saharan Africa. Agrofor Syst 38(1-3):51–76. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005948326499

Bussière F, Cellier P (1994) Modification of the soil temperature and water content regimes by a crop residue mulch: experiment and modelling. Agric For Meteorol 68(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1923(94)90066-3

Cairns JE, Hellin J, Sonder K, Araus JL, MacRobert JF, Thierfelder C, Prasanna BM (2013) Adapting maize production to climate change in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Security 5(3):345–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-013-0256-x

Cairns JE, Sonder K, Zaidi PH, Verhulst N, Mahuku G, Babu R, Nair SK, Das B, Govaerts B, Vinayan MT, Rashid Z, Noor JJ, Devi P, San Vicente F, Prasanna BM (2012) Maize production in a changing climate: impacts, adaptation, and mitigation strategies. In: Sparks D (ed) Advances in agronomy, vol 114. Academic Press, Burlington, pp 1–58

Carter J (1995) Alley farming: have resource-poor farmers benefited? Overseas Development Institute

Cheesman S, Thierfelder C, Eash NS, Kassie GT, Frossard E (2016) Soil carbon stocks in conservation agriculture systems of Southern Africa. Soil Tillage Res 156:99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2015.09.018

Chenu K, Cooper M, Hammer G, Mathews K, Dreccer M, Chapman S (2011) Environment characterization as an aid to wheat improvement: interpreting genotype–environment interactions by modelling water-deficit patterns in North-Eastern Australia. J Exp Bot 62(6):1743–1755. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erq459

Chhokar R, Sharma R, Jat G, Pundir A, Gathala M (2007) Effect of tillage and herbicides on weeds and productivity of wheat under rice–wheat growing system. Crop Prot 26(11):1689–1696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2007.01.010

Cook SM, Khan ZR, Pickett JA (2007) The use of push-pull strategies in integrated pest management. Annu Rev Entomol 52

Corbeels M, de Graaff J, Ndah TH, Penot E, Baudron F, Naudin K, Andrieu N, Chirat G, Schuler J, Nyagumbo I (2014) Understanding the impact and adoption of conservation agriculture in Africa: a multi-scale analysis. Agric Ecosyst Environ 187:155–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.10.011

Cromwell E (1990) Seed diffusion mechanisms in small farmer communities. lessons from Asia, Africa and Latin America. Network Paper-Agricultural Administration (Research and Extension) Network (United Kingdom)

Dixon J, Gulliver A, Gibbon D (2001) Global farming systems study: challenges and priorities. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy

Dorward A, Chirwa E (2011) The Malawi Agricultural Input Subsidy Programme: 2005-06 to 2008-09. Int J Agric Sustain 9:232–247. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2010.0567

Dougill AJ, Whitfield S, Stringer LC, Vincent K, Wood BT, Chinseu EL, Steward P, Mkwambisi DD (2016) Mainstreaming conservation agriculture in Malawi: knowledge gaps and institutional barriers. J Environ Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.076

Dowswell CR, Paliwal RL, Cantrell RP (1996) Maize in the third world. Westview Press, Colorado, USA

Duncan A, Tarawali S, Thorne P, Valbuena D, Descheemaeker K, Tui SH-K (2013) Integrated crop-livestock systems—a key to sustainable intensification in Africa. Tropical Grasslands-Forrajes Tropicales 1(2):202–206 doi:www.tropicalgrassland.info

Ehler LE (2006) Integrated pest management (IPM): definition, historical development and implementation, and the other IPM. Pest Manag Sci 62(9):787–789. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.1247

Ehui SK, Kang BT, Spencer DSC (1990) Economic analysis of soil erosion effects in alley cropping, no-till and bush fallow systems in South Western Nigeria. Agric Syst 34(4):349–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-521x(90)90013-g

Ekboir J (2002) CIMMYT 2000-2001 world wheat overview and outlook: developing no-till packages for small-scale farmers. CIMMYT Mexico, DF

Elliott J (1989) Soil erosion and conservation in Zimbabwe: political economy and the environment. PhD thesis, Loughborough University

Ellis F, Kutengule M, Nyasulu A (2003) Livelihoods and rural poverty reduction in Malawi. World Dev 31:1495–1510. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00111-6

Erenstein O, Sayre K, Wall P, Hellin J, Dixon J (2012) Conservation agriculture in maize- and wheat-based systems in the (sub)tropics: lessons from adaptation initiatives in South Asia, Mexico, and Southern Africa. J Sustain Agric 36(2):180–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2011.620230

FAO (2016) Special alert: delayed onset of seasonal rains in parts of Southern Africa raises serious concern for crop and live-stock production in 2016. Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS), Harare, Zimbabwe

FAOSTAT (2013) Agriculture production data 1960-2012. www.fao.org/faostat/en/

FAOSTAT (2017) http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/. Accessed 1st April 2017.

Gambiza J, Nyama C (2006) Country pasture/forage resource profiles Zimbabwe. FAO, Rome, Italy

Garrity D, Akinnifesi F, Ajayi O, Sileshi GW, Mowo JG, Kalinganire A, Larwanou M, Bayala J (2010) Evergreen Agriculture: a robust approach to sustainable food security in Africa. Food Security 2(3):197–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-010-0070-7

Gentile R, Vanlauwe B, Chivenge P, Six J (2011) Trade-offs between the short-and long-term effects of residue quality on soil C and N dynamics. Plant Soil 338(1-2):159–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-010-0360-z

Gentile R, Vanlauwe B, Van Kessel C, Six J (2009) Managing N availability and losses by combining fertilizer-N with different quality residues in Kenya. Agric Ecosyst Environ 131(3):308–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2009.02.003

Giller KE, Andersson JA, Corbeels M, Kirkegaard J, Mortensen D, Erenstein O, Vanlauwe B (2015) Beyond conservation agriculture. Front Plant Sci 6(870). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00870

Giller KE, Witter E, Corbeels M, Tittonell P (2009) Conservation agriculture and smallholder farming in Africa: the heretic’s view. Field Crop Res 114:23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2009.06.017

Glover D, Sumberg J, Andersson JA (2016) The adoption problem; or why we still understand so little about technological change in African agriculture. Outlook on Agriculture 45(1):3–6. https://doi.org/10.5367/oa.2016.0235

Godfray HCJ, Beddington JR, Crute IR, Haddad L, Lawrence D, Muir JF, Pretty J, Robinson S, Thomas SM, Toulmin C (2010) Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327(5967):812–818. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185383

Good AG, Shrawat AK, Muench DG (2004) Can less yield more? Is reducing nutrient input into the environment compatible with maintaining crop production? Trends Plant Sci 9(12):597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2004.10.008

Gourdji SM, Sibley AM, Lobell DB (2013) Global crop exposure to critical high temperatures in the reproductive period: historical trends and future projections. Environ Res Lett 8(2):024041. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024041