Abstract

Epidemiological studies have investigated the association between MDM2 promoter SNP 309 (T/G) and endometrial cancer susceptibility. However, the results are still controversial. To obtain a more precise estimate of the relationship, we conducted a meta-analysis of 1,001 cases and 1,889 controls from 6 published case–control studies (one of five articles contains two studies) to estimate the effect of SNP309 on endometrial cancer risk. The strength of association between MDM2 SNP309 and endometrial cancer susceptibility was assessed by calculating pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When all the eligible studies were pooled in the meta-analysis, we found that elevated endometrial cancer risk was significantly associated with GG variant genotype, however, heterozygous genotype TG seemed to be only a minor modifier on endometrial cancer risk (for GG vs. TT, OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.21–1.95, P = 0.0004; for TG vs. TT, OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.81–1.14, P = 0.66; for dominant model, OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.93–1.29, P = 0.29; for recessive model, OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.33–2.04, P < 0.00001). Overall, the meta-analysis suggested that the GG genotype of MDM2 SNP309 was significantly associated with the increased endometrial cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is one of the most common malignancies of the female genital tract worldwide and will occur in 2.6% of women in the United States [1]. As with all solid tumors, it is a heterogeneous disease with complex etiology, owing to genetic and environmental effects as causes or risk modifiers. It has been demonstrated that some variants in genes lead to dysfunctional DNA mismatch repair (MMR) and are therefore important in the etiology of endometrial cancer [2–4].

One important gene that has been studied is mouse double-minute 2 homolog (MDM2), a key negative regulator of p53. Amplification and/or overexpression of MDM2 have/has been found in several human cancers [5–7]. A common polymorphism of the MDM2 gene has been identified at nucleotide 309 (rs2279744, a T to G change at nucleotide 309 in the first intron). This polymorphism, which involves the second MDM2 promoter-enhancer region, increases the affinity of the promoter for the transcription activator Sp1 and results in higher levels of MDM2 mRNA and MDM2 protein. This has an oncogenic effect by reduction of P53 levels, with a consequent decrease of the TP53 apoptotic response and accumulation of genetic errors, leading to faster, and a higher frequency of, tumor formation [8–14]. Previous studies have pointed out the possible relationship between MDM2-SNP309 and the timing of cancer onset [15, 16]. Several reports have provided evidence that the G-allele of SNP309 is correlated with an increased risk of tumorigenesis [17–19].

Among women homozygous for the SNP309 variant (GG), those with estrogen-sensitive breast cancers were diagnosed 7 years earlier than those with estrogen-insensitive tumors [11]. As we know, the endometrium is estrogen-related, so, logically, SNP309 may be a candidate indicator of susceptibility to endometrial cancer.

Some genotyping studies have investigated the association between MDM2 SNP 309 and endometrial cancer risk; the correlation has not been extensively studied, however, previous experimental results remain controversial [20–24]. Results of single, relatively small studies are sometimes difficult to interpret and often conflict, and meta-analysis is useful for assessing all the evidence from such studies. Therefore, we present an updated meta-analysis conducted to give a more precise estimate of the association between MDM2 SNP309 and susceptibility to developing endometrial cancer.

Methods

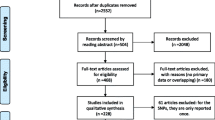

Search and selection process

We conducted a computerized search of Pubmed, the Cochrane Library, reviews, and reference lists of relevant papers using the search terms: “MDM2”, “SNP309” or “rs2279744” and “endometrial cancer”. All the indexed studies were retrieved, and the search strategy was supplemented by manually reviewing reference lists and by querying investigators working in this field. For republished and overlapping studies, only the study with the largest samples or the first published was included.

Included studies met 4 criteria:

-

1.

evaluated the association between MDM2 SNP309 and endometrial cancer risk;

-

2.

with sufficient published data to enable estimation of an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI);

-

3.

prospective or respective cohort case–control studies;

-

4.

executing Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the control group (P < 0.01).

Two reviewers (LY and HJ), unaware of the study authors and the journals in which the studies were published, independently determined whether the studies met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by joint review and consensus.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (LY and HJ), independently extracted data from published sources: the first author’s name, year of publication available online, countries of origin, ethnicity, total number of cases and controls, the numbers of cases, and controls with the MDM2 SNP309. The minimum number of patients for a study to be included was not defined. Disagreements were resolved by joint review and consensus.

Statistical analysis

Pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate the strength of association between the MDM2 SNP309 and endometrial cancer susceptibility [25]. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant; all tests and CIs were 2-sided. We first estimated the risks of the variant genotype GG and TG, compared with the wild-type TT homozygote, and then evaluated the risks of (GG + TG) versus TT and GG versus (TG + TT), assuming dominant and recessive effects of the variant G allele, respectively. The appropriateness of pooling the results from individual studies was assessed using the I 2 test for heterogeneity. The I 2 value describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance, and we considered I 2 more than 50% to indicate significant heterogeneity between the studies [26]. All analysis was initially conducted using a fixed-effects model (the Mantel–Haenszel method), and if heterogeneity across studies was observed, the analysis were repeated using a random-effects model, which includes measurement of variance in calculations using pooled results [27]. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot of effect size against standard error [28]. The analysis was carried out by using Review Manager statistical software (RevMan version 5.0.17.0; The Nordic Cochrane Center, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

Study characteristics

The main characteristics of the 6 studies included are shown in Table 1. All these studies were published in English. A total of 1,001 cases and 1,889 controls were studied. There were three studies of Caucasians, two of Asians, and one of a mixed population. All of the cases were pathologically validated. Controls were primarily healthy women that were matched for age.

Quantitative data synthesis and analysis

Data relating to the outcomes of GG versus TT, TG versus TT, dominant model (GG + TG vs. TT), and recessive model (GG vs. TG + TT) are documented in Table 2.

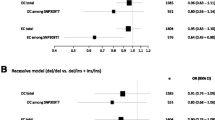

Our meta-analysis showed women with a homozygous variant genotype GG were at a greater risk of developing endometrial cancer than those with a wild-type TT genotype for the MDM2 SNP 309 (OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.21–1.95, P = 0.0004) (Fig. 1).

However, there was no significant statistical difference in the incidence of endometrial cancer between women with TG genotype and women with TT genotype (OR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.81–1.14, P = 0.66) (Fig. 2).

The meta-analysis of the dominant model showed no significant relationship between GG + TG genotype and an increased risk of the development of endometrial cancer compared with the TT genotype (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.93–1.29, P = 0.29) (Fig. 3).

Significantly elevated endometrial cancer risk was also associated with GG variant genotype in the recessive model when all the eligible studies were pooled in the meta-analysis (OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.33–2.04, P < 0.00001) (Fig. 4).

Because the between-study heterogeneity of each analysis in our meta-analysis was not statistically significant, all pooled ORs were derived from fixed-effects models.

Publication bias

This was assessed by use of 4 funnel plots (Fig. 5). The funnel plots for GG versus TT, TG versus TT, dominant model (GG + TG vs. TT), and recessive model (GG vs. TG + TT) seemed to be symmetric, suggesting the absence of publication bias.

Discussion

With the completion of the Human Genome Project, we have reached a new genomic era in science. A large number of polymorphisms have been identified and several of these have been analyzed for association with changes in cell-cycle control [29]. Investigation of SNPs in genes and pathways known to probably affect carcinogenesis are good candidates for study.

MDM2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, suppresses the activity of p53 transcription and targeting p53 protein for ubiquitin-mediated degradation [30–32]. It directly binds to p53 and acts as a crucial negative regulator for maintaining function of p53 by modulating its activity, location, and stability [33]. Thus, increased MDM2 levels and a consequent functional decrease in p53 activity could enable cells with DNA damage to escape growth regulation, resulting in faster, and a higher frequency of, carcinogenesis. Besides this crucial function, MDM2 is also capable of mediating p53-independent tumorigenicity; this is not yet well understood [34].

The study by Bond et al. [9] revealed a twofold increase of the MDM2 protein in cell lines with the heterozygous (TG) genotype and a fourfold increase in cell lines with the homozygous variant (GG) genotype, compared with cell lines with the homozygous wild (TT) genotype. Previous studies also showed a functional effect of MDM2 SNP309 on cell lines [9, 35, 36]. It has been shown that women with variant genotypes (GG + GT) had a greater likelihood of having a higher-grade (grade 2 or 3) endometrial cancer than those with wild-type genotype (TT) [20]. On the basis of the results of our meta-analysis, we might speculate a higher-grade endometrial cancer is significantly more associated with GG variant genotype. Furthermore, during investigation of the effect of the 309G allele on the age of tumor onset a gender-specific effect was observed—the age of cancer diagnosis is younger in women but not in men affected by STS, B cell lymphoma [11], and breast cancer [37]. Also, a number of studies have revealed a possible gender difference in colorectal and non-small cell lung cancer susceptibility with regard to this genetic polymorphism [12, 17]. Several reports have shown that higher MDM2 levels were expressed in ER-positive tumors or cell lines rather than in ER-negative ones [38–41]. Because SNP309 is located in the promoter region where ER binds and leads to MDM2 gene transcription, MDM2 expression levels could be affected by estrogen signaling through an interaction of estrogen receptor (ER) with a region of the promoter. The G-allele of SNP309 accelerates tumor formation more strongly in women because it increases affinity for Sp1, a co-transcriptional activator of the estrogen receptor known to participate in estrogen-mediated gene transcription [42, 43]. The results discussed above suggest a pathway in which MDM2 SNP309 might cooperate with estrogen-signaling to increase MDM2 levels, with consequent increased susceptibility to endometrial cancer. Moreover, because type I endometrial cancer is related to hyperestrogenism whereas type II cancer is unrelated to estrogen, type I endometrial cancer is significantly more associated with the GG genotype.

Several studies have found a significant association between MDM2 SNP309 and endometrial cancer risk [21–24], whereas others have found no such association [20, 21]. In order to resolve this controversy, we performed this meta-analysis of 6 studies, including 1,001 cases and 1,889 controls, for better evaluation of the association.

This is the first meta-analysis to demonstrate the association between risk of endometrial cancer and MDM2 SNP309 using eligible studies. On the basis of 6 case–control studies focused on MDM2 SNP309 and endometrial cancer risk, our meta-analysis provided evidence that women with a homozygous variant genotype were at greater risk of endometrial cancer whereas the increased risk in those with a heterozygous genotype TG was less significant. The dominant model showed no significant relationship between GG + TG genotype and an increased risk of development of endometrial cancer compared with the TT genotype, but the GG genotype was significantly associated with an increased risk of development of endometrial cancer compared with the TG + TT genotype.

However, attention should be drawn to some limitations of the study. First, the controls in the studies included were not uniformly defined. Second, data were not stratified by other factors. Therefore, further precise analysis should be performed if more detailed individual data become available, for example grade of endometrial cancer, age of endometrial cancer onset or diagnosis, basal metabolic index, menopausal status, use of contraceptives, use of postmenopausal hormones, smoking and drinking status, and environmental factors.

On the basis of this analysis, women with MDM2 SNP309 GG genotypes have an approximate 65% increased risk of development endometrial cancer, a result which is statistically significant (OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.33–2.04). The result of our meta-analysis suggests SNP309 could be a marker warning of endometrial cancer occurrence. Further studies on the functions of MDM2-SNP309 genotypes and their cooperation with the estrogen-signaling pathway, biological correlation with genetic backgrounds, chemo-sensitivity, cell cycle regulation, and apoptosis would definitely aid better understanding of the pathogenesis and clinical management of endometrial cancer.

References

Bakkum-Gamez JN, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Laack NN, Mariani A, Dowdy SC. Current issues in the management of endometrial cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(1):97–112.

Olson SH, Bandera EV, Orlow I. Variants in estrogen biosynthesis genes, sex steroid hormone levels, and endometrial cancer: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(3):235–45.

Ghasemi N, Karimi-Zarchi M, Mortazavi-Zadeh MR, Atash-Afza A. Evaluation of the frequency of TP53 gene codon 72 polymorphisms in Iranian patients with endometrial cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;196(2):167–70.

Goodfellow PJ, Buttin BM, Herzog TJ, Rader JS, Gibb RK, Swisher E, et al. Prevalence of defective DNA mismatch repair and MSH6 mutation in an unselected series of endometrial cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(10):5908–13.

Oliner JD, Kinzler KW, Meltzer PS, George DL, Vogelstein B. Amplification of a gene encoding a p53-associated protein in human sarcomas. Nature. 1992;358(6381):80–3.

Rayburn E, Zhang R, He J, Wang H. MDM2 and human malignancies: expression, clinical pathology, prognostic markers, and implications for chemotherapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5(1):27–41.

Momand J, Jung D, Wilczynski S, Niland J. The MDM2 gene amplification database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(15):3453–9.

Michael D, Oren M. The p53 and Mdm2 families in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12(1):53–9.

Bond GL, Hu W, Bond EE, Robins H, Lutzker SG, Arva NC, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 promoter attenuates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and accelerates tumor formation in humans. Cell. 2004;119(5):591–602.

Bond GL, Hu W, Levine A. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 gene: from a molecular and cellular explanation to clinical effect. Cancer Res. 2005;65(13):5481–4.

Bond GL, Hirshfield KM, Kirchhoff T, Alexe G, Bond EE, Robins H, et al. MDM2 SNP309 accelerates tumor formation in a gender-specific and hormone-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2006;66(10):5104–10.

Lind H, Zienolddiny S, Ekstrom PO, Skaug V, Haugen A. Association of a functional polymorphism in the promoter of the MDM2 gene with risk of nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(3):718–21.

Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Kirchoff T, Erill N, Offit K, Bochner BH, et al. A polymorphism in HDM2 (SNP309) associates with early onset in superficial tumors, TP53 mutations, and poor outcome in invasive bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(11):3215–20.

Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387(6630):296–9.

Menin C, Scaini MC, De Salvo GL, Biscuola M, Quaggio M, Esposito G, et al. Association between MDM2-SNP309 and age at colorectal cancer diagnosis according to p53 mutation status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(4):285–8.

Lum SS, Chua HW, Li H, Li WF, Rao N, Wei J, et al. MDM2 SNP309 G allele increases risk but the T allele is associated with earlier onset age of sporadic breast cancers in the Chinese population. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(4):754–61.

Alhopuro P, Ylisaukko-Oja SK, Koskinen WJ, Bono P, Arola J, Jarvinen HJ, et al. The MDM2 promoter polymorphism SNP309T–>G and the risk of uterine leiomyosarcoma, colorectal cancer, and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Med Genet. 2005;42(9):694–8.

Bougeard G, Baert-Desurmont S, Tournier I, Vasseur S, Martin C, Brugieres L, et al. Impact of the MDM2 SNP309 and p53 Arg72Pro polymorphism on age of tumour onset in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43(6):531–3.

Hong Y, Miao X, Zhang X, Ding F, Luo A, Guo Y, et al. The role of P53 and MDM2 polymorphisms in the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9582–7.

Ashton KA, Proietto A, Otton G, Symonds I, McEvoy M, Attia J, et al. Polymorphisms in TP53 and MDM2 combined are associated with high grade endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113(1):109–14.

Terry K, McGrath M, Lee IM, Buring J, De Vivo I. MDM2 SNP309 is associated with endometrial cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(4):983–6.

Nunobiki O, Ueda M, Yamamoto M, Toji E, Sato N, Izuma S, et al. Polymorphisms of p53 codon 72 and MDM2 promoter 309 and the risk of endometrial cancer. Hum Cell. 2009;22(4):101–6.

Ueda M, Yamamoto M, Nunobiki O, Toji E, Sato N, Izuma S, et al. Murine double-minute 2 homolog single nucleotide polymorphism 309 and the risk of gynecologic cancer. Hum Cell. 2009;22(2):49–54.

Walsh CS, Miller CW, Karlan BY, Koeffler HP. Association between a functional single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 gene and sporadic endometrial cancer risk. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104(3):660–4.

Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–48.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291(5507):1304–51.

Chen J, Wu X, Lin J, Levine AJ. mdm-2 inhibits the G1 arrest and apoptosis functions of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(5):2445–52.

Cheah PL, Looi LM. p53: an overview of over two decades of study. Malays J Path. 2001;23(1):9–16.

Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387(6630):299–303.

Harris SL, Levine AJ. The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene. 2005;24(17):2899–908.

Bouska A, Eischen CM. Mdm2 affects genome stability independent of p53. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):1697–701.

Arva NC, Gopen TR, Talbott KE, Campbell LE, Chicas A, White DE, et al. A chromatin-associated and transcriptionally inactive p53-Mdm2 complex occurs in mdm2 SNP309 homozygous cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):26776–87.

Harris SL, Gil G, Robins H, Hu W, Hirshfield K, Bond E, et al. Detection of functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms that affect apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(45):16297–302.

Schmidt MK, Reincke S, Broeks A, Braaf LM, Hogervorst FB, Tollenaar RA, et al. Do MDM2 SNP309 and TP53 R72P interact in breast cancer susceptibility? A large pooled series from the breast cancer association consortium. Cancer Res. 2007;67(19):9584–90.

Gudas JM, Nguyen H, Klein RC, Katayose D, Seth P, Cowan KH. Differential expression of multiple MDM2 messenger RNAs and proteins in normal and tumorigenic breast epithelial cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1(1):71–80.

Phelps M, Darley M, Primrose JN, Blaydes JP. p53-independent activation of the hdm2-P2 promoter through multiple transcription factor response elements results in elevated hdm2 expression in estrogen receptor alpha-positive breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63(10):2616–23.

Bueso-Ramos CE, Manshouri T, Haidar MA, Yang Y, McCown P, Ordonez N, et al. Abnormal expression of MDM-2 in breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;37(2):179–88.

Okumura N, Saji S, Eguchi H, Nakashima S, Saji S, Hayashi S. Distinct promoter usage of mdm2 gene in human breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2002;9(3):557–63.

Schultz JR, Petz LN, Nardulli AM. Cell- and ligand-specific regulation of promoters containing activator protein-1 and Sp1 sites by estrogen receptors alpha and beta. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(1):347–54.

Safe S. Transcriptional activation of genes by 17 beta-estradiol through estrogen receptor-Sp1 interactions. Vitam Horm. 2001;62:231–52.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this study declare there are no applicable conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Y. Li and H. Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhao, H., Sun, L. et al. MDM2 SNP309 is associated with endometrial cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Human Cell 24, 57–64 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13577-011-0013-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13577-011-0013-4