Abstract

This study examines historical trends in poverty using an anchored version of the U.S. Census Bureau’s recently developed Research Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) estimated back to 1967. Although the SPM is estimated each year using a quasi-relative poverty threshold that varies over time with changes in families’ expenditures on a core basket of goods and services, this study explores trends in poverty using an absolute, or anchored, SPM threshold. We believe the anchored measure offers two advantages. First, setting the threshold at the SPM’s 2012 levels and estimating it back to 1967, adjusted only for changes in prices, is more directly comparable to the approach taken in official poverty statistics. Second, it allows for a better accounting of the roles that social policy, the labor market, and changing demographics play in trends in poverty rates over time, given that changes in the threshold are held constant. Results indicate that unlike official statistics that have shown poverty rates to be fairly flat since the 1960s, poverty rates have dropped by 40 % when measured using a historical anchored SPM over the same period. Results obtained from comparing poverty rates using a pretax/pretransfer measure of resources versus a post-tax/post-transfer measure of resources further show that government policies, not market incomes, are driving the declines observed over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Poverty measures set a poverty line or threshold and then evaluate resources against that threshold. The United States’ official poverty measure (OPM) is widely viewed as flawed on both counts: it uses thresholds that are outdated and are not adjusted appropriately for the needs of different types of individuals and households, and it uses an incomplete measure of resources that fails to take into account the full range of income and expenses of individuals and households. Because of these (and other) failings, statistics using the OPM do not provide an accurate picture of income poverty or the role of government policies in combating income poverty.Footnote 1

To address these limitations, the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) recently implemented a Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which applies a set of thresholds based on contemporary expenditures and a more comprehensive measure of resources. The Census Bureau has released SPM statistics for 2009–2014 (Short 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015). From these reports, we know that using the SPM results in a higher overall threshold and more income (e.g., by including the value of in-kind transfers and subsidies in resources), but it also subtracts more expenses (e.g., childcare, medical expenses) from resources.

In recent work, researchers have produced historical SPM estimates for the period 1967–2012, using data on incomes from the 1968–2013 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to the Current Population Survey (March CPS) and data on expenditures from the 1961, 1972/1973, and 1980–2012 Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) (see Fox et al. 2015). Those estimates showed that government policies have played a more important role in reducing poverty, particularly in recent years, than suggested by the OPM.

The Census Bureau and BLS SPM methodology uses five years of CE data to calculate moving average thresholds for each year (see Garner 2010). These thresholds are quasi-relative, in that the SPM methodology applies the same metric—the 30th to 36th percentile of expenditures on food, clothing, shelter, and utilities, plus 20 % more to cover other essentials—to define the poverty line over time.Footnote 2 For a discussion of trends in poverty using a quasi-relative measure, see Fox et al. (2015).

However, because the SPM measure is quasi-relative, historical changes in poverty could be at least partly due to changes in thresholds. In this respect, an anchored or absolute measure can provide a cleaner estimate of the role of resources in affecting trends in poverty. Thus, although a relative or quasi-relative measure may be more appropriate for assessing the level of need in any given year, we argue that an anchored measure is more useful for establishing how families’ resources have changed against a fixed benchmark because an anchored poverty threshold takes changes in living standards out of the equation when assessing changes in poverty over time. In this sense, an anchored SPM provides a middle ground between the OPM (which is flawed on both the resource and the threshold side) and the SPM (which corrects issues on both sides but, in doing so, introduces a quasi-relative threshold, making the disentangling of processes more difficult). The anchored SPM offers an intermediate measure: it updates the threshold to modern consumption norms, but instead of adjusting this on a quasi-relative basis over time, it adjusts only for inflation, as the official measure does. This approach reveals what poverty trends would be if resources were measured comprehensively against a contemporary threshold but without moving to a quasi-relative concept.Footnote 3

In this research note, we therefore report results using an alternative poverty measure that uses today’s threshold and carries it back historically by adjusting it for inflation. Because this alternative measure is anchored with today’s SPM threshold, we refer to as an “anchored supplemental poverty measure” (anchored SPM). We see this as a particularly appropriate measure with which to estimate progress on poverty because it uses a comprehensive measure of income and expenses, evaluated against a fixed contemporary threshold.

In our key results, we distinguish between trends in poverty rates, where poverty is calculated using pretax/pretransfer resources versus post-tax/post-transfer resources. The former will be driven by changes in market income over time (reflecting changes in family characteristics and family structure as well as changes in employment and earnings of various groups), while the latter will present trends after social policy responses to underlying demographic and labor market realities are taken into account. Splitting the data this way allows us to more cleanly tease apart the effects of changes in market incomes from the effects of social policies in accounting for changes in poverty rates over time.

Data and Methods

We construct our anchored SPM using data from the 2008–2012 CE and the 1968–2013 ASEC to the CPS to derive the poverty unit, the poverty threshold, and the poverty unit’s resources in each year. A full description of the methods can be found in Fox et al. (2015).

Poverty Unit

The poverty unit for the anchored SPM is the same as in the SPM. Although the poverty unit under the official definition is based on families, under the SPM, the concept of the poverty unit is broadened to include unmarried partners (and their children/family members), unrelated children under age 15, and foster children under age 22 (when identifiable). All resources and nondiscretionary expenses are pooled across members of the poverty unit to determine poverty status.

Anchored SPM Thresholds

To set the anchored SPM thresholds, we first set thresholds for 2012. Specifically, following the Census Bureau and BLS methodology, we construct poverty thresholds using a five-year moving average of 2008–2012 CE data on out-of-pocket expenditures on food, clothing, shelter, and utilities (FCSU) by consumer units with exactly two children. All expenditures are adjusted by a three-parameter equivalence scale (Betson and Michael 1993) and then ranked into percentiles. The average FCSU for the 30th to 36th percentile of FCSU expenditures is then multiplied by 1.2 to account for additional basic needs. We then use equivalence scales to set thresholds for all family configurations. Following the Census Bureau and BLS methodology, we produce thresholds for three housing-status groups: owners with a mortgage, owners without a mortgage, and renters. The SU (shelter, utilities) portion of the FCSU is estimated separately for each housing-status group. After we establish the thresholds for 2012, we then carry them back historically by adjusting for inflation using the Consumer Price Index Research Series (CPI-U-RS), the Census Bureau’s preferred series for overall changes in inflation over time.Footnote 4

Resources

Anchored SPM resources include after-tax income plus a variety of in-kind benefits—the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the National School Lunch Program; the Women, Infants, and Children program (WIC); Housing Assistance; and the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)—minus medical out-of-pocket expenditures and work-related expenses, including childcare expenses. Because taxes, in-kind benefits, and expenses have become available in the March CPS only at various points in time since 1967, we impute values for years when they are unavailable.Footnote 5

Results

Anchored SPM Versus OPM Poverty Rates

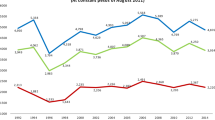

Figure 1 presents trends in poverty for the total population using the anchored SPM versus official statistics. The OPM line displays the familiar pattern, with poverty at 14 % in 1967 and 15 % in 2012. The anchored SPM line, however, tells a very different story, with poverty falling from nearly 26 % in 1967 to 16 % in 2012—a drop of approximately 40 %. We also show, for illustrative purposes, the same trend using a poverty threshold anchored in 1967 living standards.Footnote 6 This trend line shows a very similar drop in poverty rates over time, albeit from a lower starting level. Although living standards, as measured by consumer expenditures, have increased over time, income poverty rates have fallen substantially when measured against a fixed threshold, no matter whether that threshold is set in 1960s or contemporary times.

Figures 2, 3, and 4 present anchored SPM versus OPM poverty rates for children, working-age adults, and the elderly, respectively. The overall trends for the total population are mirrored in the trend for the largest group: working-age adults (Fig. 3). However, the story is different for children and the elderly. As shown in Fig. 2, child poverty is higher with the anchored SPM than the OPM for most of the period, yet with a crossover in the late 2000s, a period when important elements of the safety net not counted in OPM were expanded (as we discuss further shortly).

By contrast, as shown in Fig. 4, poverty among the elderly is consistently higher with the anchored SPM than with the OPM. This finding reflects the fact that most resources reaching the elderly are counted in both measures, but only the SPM subtracts medical expenses—a particularly important item for this group.

The Role of Government Programs

In this section, we use the anchored SPM to calculate a set of counterfactual estimates of what poverty rates would look like if we did not take taxes and government transfers into account.Footnote 7 We provide estimates for the total population and for children, given that many of the transfer programs are aimed at children.

We begin, in Fig. 5, by showing poverty rates for the total population with and without taxes and government transfers. “Taxes” include taxes that reduce income (payroll taxes, federal and state income taxes) as well as tax programs that increase income (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and other tax credits). Government transfers include food and nutrition programs (SNAP/food stamps, school lunch, WIC); other means-tested transfers (Supplemental Security Income (SSI), cash welfare (i.e., Temporary Assistance for Needy Families/Aid to Families with Dependent Children (TANF/AFDC)), housing subsidies, LIHEAP); and social insurance programs (Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, Workers Compensation, Veterans Compensation, and government pensions). The dash-dotted line in the Fig. 5 shows the anchored SPM poverty rate when taking into account all these taxes and transfers; the solid line shows what poverty rates would be if taxes and transfers were not taken into account. The dashed line shows the percentage point difference between these two rates.

Figure 5 shows the substantial and growing role of taxes and transfer payments. Using the pretax/pretransfer measure, we find that poverty would have actually increased slightly over the period, from 27 % to nearly 29 %. After accounting for taxes and transfers, however, poverty would have fallen by approximately 40 %, from 26 % to 16 %. The figure also shows the growing role of taxes and transfers in reducing poverty, from only about 1 percentage point in 1967 to nearly 13 percentage points in 2012. To look separately at the role of taxes versus transfers, we can estimate poverty rates first absent all taxes and then absent all other transfers. For simplicity, we focus on 1967 and 2012, the beginning and end points of our time series. Absent taxes, the poverty rate in 1967 would be estimated at 22.4 % instead of 25.6 %. In 2012, it would be 17.3 % instead of 16.0 %. Thus, in 1967, the tax system raised poverty rates; in 2012, though, the net result was to lower poverty rates, suggesting a growing role of the tax system in generating poverty reduction. If we instead calculate poverty rates absent government transfers (i.e., cash and noncash transfers, excluding those that come through the tax system), we find that poverty would have been 30.7 % in 1967 (instead of 25.6 %) and 28.5 % in 2012 (instead of 16 %). This suggests a growing role of transfers in reducing poverty rates over time. We find that noncash benefits reduce poverty rates by 2.4 percentage points in 2012 in the overall population (and 4.5 percentage points among children). Thus, we find that both taxes and transfers are important contributors to the decline over time.Footnote 8

Figure 6 presents similar estimates but for deep poverty (i.e., the share of the total population with incomes below 50 % of the SPM poverty line). This figure illustrates the important role that taxes and transfers play in reducing rates of deep poverty, particularly during economic downturns. Deep poverty rates hover around 5 % for most of the period (except in the first several years), but the counterfactual line shows that without taxes and transfers, deep poverty rates would instead range from 15 % to 20 %.

Figures 7 and 8 present similar estimates but for poverty and deep poverty, respectively, among children. Here, the growing role of taxes and transfers—and particularly newly counted SPM taxes and transfers—is particularly striking. By 2012, estimates that did not count the resources from noncash transfers and the tax system would find child poverty at 30 % and deep child poverty at 17 %, rather than 19 % and 5 %, respectively.

Conclusion

Having accurate data on trends in poverty is crucial to assessing progress on poverty reduction. Although both the Census Bureau’s SPM and historical SPM measures use a quasi-relative poverty threshold to examine changes in poverty rates, an anchored threshold provides more direct evidence on the competing roles of demographic and labor market changes versus social policy responses in accounting for changes in poverty over time resulting from resources alone. Our anchored SPM measure clearly documents the role that government policies and programs have played in shaping poverty trends over time: changes on this measure stem primarily from changes in underlying resources available to families rather than changes in living standards or needs as embodied by the poverty thresholds.

Our estimates using an anchored SPM—which holds SPM thresholds constant over time—show that historical trends in poverty have been more favorable (and that government programs have played a larger role) than the estimates using the official poverty measure suggest. The OPM shows the overall poverty rates to be nearly the same in 1967 and 2012—at 14 % and 15 %, respectively. However, our counterfactual estimates using an anchored SPM show that without government tax and transfer programs, poverty would have been roughly flat at 27 % to 29 %; but with government programs, poverty has fallen from 26 % to 16 %—a 40 % reduction. Government programs today are cutting poverty nearly in half (from 29 % to 16 %), but in 1967, government programs lowered poverty by only about 1 percentage point. These effects might be somewhat overstated if pretax/pretransfer poverty rates were lower than we estimate in the absence of government policies and programs—that is, if behavior changed in response to the absence of programs. However, as noted earlier, we believe that such effects are likely small in the aggregate.

Results are particularly striking for child poverty and deep child poverty. In 2012, government programs reduced both child poverty and deep child poverty by 11 percentage points. By contrast, in 1967, government programs (through the tax system) actually slightly increased child poverty rates and reduced deep child poverty rates by only 4.5 percentage points. Estimates with the OPM would miss much of this poverty reduction, particularly in the modern period because after-tax and in-kind benefits have grown in importance. Our anchored SPM thus shows the importance of accounting for a comprehensive array of government programs when estimating trends in poverty and in gauging the role of government programs in making progress on poverty.

In contrast to some estimates in the literature (e.g., Meyer and Sullivan 2012c), we find that both taxes and transfers have been important in driving long-term declines in estimated poverty rates. In particular, we find a larger role of noncash benefits—particularly food stamps and housing—in the modern period, reducing poverty rates by 2.4 percentage points in 2012 in the overall population and 4.5 percentage points among children. Further exploring the role of noncash benefits is a topic worthy of future research.

Note that even the results presented here do not fully account for the total effect of taxes and transfers on estimated poverty rates. First, the trends presented here do not correct for the growing underreporting of government benefits over time (Meyer et al. 2009). Correcting for such underreporting would likely make the declines in poverty, associated with social policies and programs, documented here even more dramatic. Second, the estimates provided here do not explicitly account for the role of government health insurance programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid, or for the role of childcare subsidies. Both medical and childcare expenses are accounted for in the SPM only implicitly, through the reduction in resources after expenditures are subtracted from income. The total effect of taxes and transfers on poverty rates would likely be even greater if the effects of these programs were explicitly taken into account. Correcting for underreporting of public benefits and accounting for medical and childcare policies remain important areas for future research documenting trends in poverty over time.

Notes

See Blank and Greenberg (2008), Citro and Michael (1995), and Hutto et al. (2011) for discussions of the adequacy of the official poverty measure and improved income-poverty measures. Some scholars prefer a consumption-based to an income-based measure of poverty, arguing that consumption provides a better measure of overall economic well-being than income (Meyer and Sullivan 2012a, b, c). We do not take up that debate here, but note that trends using consumption and income poverty, when properly measured, line up fairly well (Bavier 2008; Council of Economic Advisers 2014).

Official poverty thresholds are based on an entirely different concept and were based on food costs as a percentage of total family budgets in the 1950s and 1960s.

Contemporary SPM thresholds will include food spending derived from SNAP benefits. One might prefer a threshold that doesn’t include such spending if one wanted a fully complete accounting of the total effect of the role of government policies and programs in reducing the poverty rate.

Official poverty thresholds are updated annually using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) and historically were updated first using changes in food prices and then using the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) (Fisher 1998). The CPI-U-RS is thought by many economists to be superior to the CPI-U in that it corrects for many known biases in early years. Some economists, however, have argued that even the CPI-U-RS does not go far enough to correct such biases (for a discussion, see Meyer and Sullivan 2012b). Note that the shelter component of the CPI-U-RS is based on rental equivalence of housing rather than shelter spending per se: an inflation index based on spending alone might be preferable for consistency’s sake. However, despite these limitations, we believe the CPI-U-RS to be the best measure for consistently adjusting prices over the period.

Details on the imputation procedures and sensitivity thereof can be found in Fox et al. (2015: technical appendix). Among those items imputed, medical out-of-pocket (MOOP) expenses lead to the biggest difference in poverty rates in any given year and must be imputed for the entire time series. (Actual MOOP expenses are available in the CPS starting in 2010 for calendar year 2009, but we use our imputation procedure for the entire time series for consistency’s sake.) However, findings are robust to whether MOOP is considered at all. For other programs, such as SNAP and WIC, we impute only in the early years of our study period, when these programs were still fairly small. Mean imputed benefits constituted approximately 9 % of total estimated government benefits in our sample in years prior to 1979.

See Fox et al. (2015) for the derivation of the 1967 threshold. This threshold is then adjusted annually for inflation using the CPI-U-RS.

These counterfactual estimates indicate, in an accounting sense, how much taking government taxes and transfers into account alters our estimates of poverty. Because we do not model potential behavioral responses to the programs, these estimates cannot reveal what actual poverty rates would be in the absence of the programs. However, because research suggests that these behavioral effects are small, the estimates are useful first approximations (Ben-Shalom et al. 2011).

Detailed results are available upon request. Meyer and Sullivan (2012c) conducted a similar analysis for taxes and noncash benefits, finding a large effect of the tax system but a small role for noncash transfers. One source of difference is that we study the effect of all transfers—cash and noncash—whereas Meyer and Sullivan compared poverty estimates based on money income, which would include cash transfers, with poverty estimates based on money income plus taxes and in-kind transfers. Meyer and Sullivan also adjusted for the fungible value of Medicare and Medicaid, employer health benefits, and the net return on housing equity. We do not make these adjustments. Our results for the decline in poverty over time are substantively similar if we make all other changes except for the exclusion of MOOP from resources. Ignoring MOOP, we would find that poverty (measured against 2012 anchored thresholds) declined from 22.8 % to 12.5 %, or about a 45 % decline.

References

Bavier, R. (2008). Reconciliation of income and consumption data in poverty measurement. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27, 40–62.

Ben-Shalom, Y., Moffitt, R., & Scholz, J. K. (2011). An assessment of the effectiveness of anti-poverty programs in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.npc.umich.edu/publications/working_papers/

Betson, D., & Michael, R. (1993) A recommendation for the construction of equivalence scales (Unpublished memorandum prepared for the Panel on Poverty and Family Assistance, Committee on National Statistics, National Research Council). South Department of Economics, University of Notre Dame, South Bend, IN.

Blank, R. M., & Greenberg, M. H. (2008). Improving the measurement of poverty (The Hamilton Project Discussion Paper No. 2008-17). Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Citro, C. F., & Michael, R. T. (Eds.). (1995). Measuring poverty: A new approach. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Council of Economic Advisers. (2014). The war on poverty 50 years later (Progress report). Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President of the United States.

Fisher, G. M. (1998). Setting American standards of poverty: A look back. Focus, 19, 47–52.

Fox, L., Wimer, C., Garfinkel, I., Kaushal, N., & Waldfogel, J. (2015). Waging war on poverty: Poverty trends using a historical supplemental poverty measure. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 34, 567–592.

Garner, T. (2010). Supplemental poverty measure thresholds: Laying the foundation (BLS report). Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Hutto, N., Waldfogel, J., Kaushal, N., & Garfinkel, I. (2011). Improving the measurement of poverty. Social Service Review, 85, 39–74.

Meyer, B. D., Mok, W. K. C., & Sullivan, J. X. (2009). The under-reporting of transfers in household surveys: Its nature and consequences (NBER Working Paper No. 15181). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Meyer, B. D., & Sullivan, J. X. (2012a). Identifying the disadvantaged: Official poverty, consumption poverty, and the new supplemental poverty measure. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 111–136.

Meyer, B. D., & Sullivan, J. X. (2012b). Consumption and income poverty in the United States. In P. N. Jefferson (Ed.), Oxford handbook of the economics of poverty (pp. 49–74). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Meyer, B. D., & Sullivan, J. X. (2012c). Winning the war: Poverty from the Great Society to the Great Recession. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 45(2), 133–200.

Short, K. (2011). The research supplemental poverty measure: 2010 (Current Population Reports P60-241). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Short, K. (2012). The research supplemental poverty measure: 2011 (Current Population Reports P60-244). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Short, K. (2013). The research supplemental poverty measure: 2012 (Current Population Reports P60-247). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Short, K. (2014). The research supplemental poverty measure: 2013 (Current Population Reports P60-251). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Short, K. (2015). The research supplemental poverty measure: 2014 (Current Population Reports P60-254). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for funding support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation and from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through grant R24 HD058486-03 to the Columbia Population Research Center (CPRC). We benefited from research assistance from Madeleine Gelblum, Nathan Hutto, JaeHyun Nam, and Ethan Raker. We are also grateful to seminar participants at CPRC and Russell Sage Foundation, as well as many colleagues who provided helpful insights and advice, in particular, Jodie Allen, Ajay Chaudry, Sheldon Danziger, Daniel Feenberg, Gordon Fisher, Jason Furman, Thesia Garner, Charles Hokayem, David Johnson, Mark Levitan, Jordan Matsudaira, Laryssa Mykyta, Trudi Renwick, Kathy Short, Tim Smeeding, and Betsy Stevenson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wimer, C., Fox, L., Garfinkel, I. et al. Progress on Poverty? New Estimates of Historical Trends Using an Anchored Supplemental Poverty Measure. Demography 53, 1207–1218 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0485-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0485-7