Abstract

The rise of cohabitation in family process among American young adults and declining rates of marriage among cohabitors are considered by some scholars as evidence for the importance of society-wide ideational shifts propelling recent changes in family. With data on two cohabiting cohorts from the NSFG 1995 and 2006–2010, the current study finds that marriage rates among cohabitors have declined steeply among those with no college degree, resulting in growing educational disparities over time. Moreover, there are no differences in marital intentions by education (or race/ethnicity) among recent cohabitors. We discuss how findings of this study speak to the changes in the dynamics of social stratification system in the United States and suggest that institutional and material constraints are at least as important as ideational accounts in understanding family change and family behavior of contemporary young adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The rise of cohabitation in the courtship process has made it the modal pathway to marriage. About two-fifths of women in the United States who married in the early 1980s cohabited first, but recent data show that two-thirds of first marriages are preceded by cohabitation (Kennedy and Bumpass 2011; Manning 2010). Even as cohabitation has increasingly become a part of the marriage process, a declining proportion of cohabitations transition into marriage, and an increasing proportion dissolve within three years of initiation (Guzzo 2014; Kennedy and Bumpass 2008). Some researchers have suggested that these trends represent a broader process of deinstitutionalization of marriage at least partly due to ideational change that emphasizes individual autonomy and gender equality (Cherlin 2004; Lesthaeghe 1995; Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa 1986).

Yet, trends in marriage and marital stability indicate that the consequences of these society-wide shifts in expectations about marriage are realized differently across the socioeconomic spectrum (Ellwood and Jencks 2004; McLanahan 2004). The proportion of women who will ever marry is declining across all socioeconomic groups, but these declines are projected to be much more pronounced for women without a college degree and African Americans than for college-educated whites (Goldstein and Kenney 2001; Martin et al. 2014). Similarly, education has long been negatively associated with divorce, but this difference is growing (Martin 2006; Raley and Bumpass 2003). In fact, the proportion projected to marry by age 40 has declined little for college-educated women and men (Martin et al. 2014), and marital stability appears to have increased for this group as well (Martin 2006). Thus, in the context of society-wide shifts in gender norms and marriage expectations, recent divergence in marriage and divorce may be strongly linked to inequalities in the opportunity structure.

The goal of this research is to investigate whether trends in cohabitation outcomes are similarly diverging and, if so, whether socioeconomic differences in these outcomes are related to lower expectations for marriage among disadvantaged cohabitors. The rise in cohabitation has been a signature theme of the second demographic transition and deinstitutionalization of marriage arguments, and the weakening link between cohabitation and marriage supports the predictions of these accounts of family change. However, past research has also indicated that economic constraints are a key factor in cohabitors’ decisions to marry (Manning and Smock 1995, 2005; Oppenheimer 2003; Smock et al. 2005). As widespread social changes have made marriage optional, the standards for marriage have risen so that it is a capstone rather than cornerstone of economic security (Cherlin 2004). This may be an additional contributor to recent declines in marriage among cohabitors. To achieve our research goal, we use data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) 1995 and 2006–2010.

Background

Two perspectives on recent changes in family behavior lay the foundation for developing expectations about trends in union transitions among cohabitors and how these trends diverge across racial/ethnic and educational groups. One perspective is the second demographic transition (SDT) model, discussed in the following section (Lesthaeghe 1995; Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa 1986; van de Kaa 1987). The other perspective is the diverging destinies thesis, which emphasizes the fact that family change is not uniform for all Americans but instead reflects a growing social divide in family formation behavior between the socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged (McLanahan 2004).

Model of Second Demographic Transition

Developed by Lesthaeghe and van de Kaa to differentiate recent trends in family formation and fertility from patterns described in the first demographic transition, the SDT is characterized by changes in a wide array of family behavior that began in 1960s in Nordic countries, including the rise of cohabitation (see Lesthaeghe and Neidert 2006). The SDT perspective suggests that the trends in different aspects of family behavior, such as the rise of cohabitation, increasing postponement of marriage, and increase in nonmarital childbearing, are all due to the growing emphasis on individualism, fueled by such social changes as modernization and women’s growing economic independence (Lesthaeghe 1995).

Based on the experiences in Sweden and other Nordic countries, the SDT model outlines a developmental course for cohabitation, suggesting that cohabitation may first emerge as a deviant status; however, as it becomes more prevalent, it moves to a prelude to marriage, and then ultimately cohabitation becomes a union setting equivalent to marriage. Cohabitation has been established as a normal (even normative) stage in the marriage process for at least 20 years, with more than one-half of marriages initiated in the early 1990s having been preceded by cohabitation (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008). Since the 1990s, a declining proportion of unions transition into marriage (Guzzo 2014), a fact consistent with the predictions of the SDT that serves as evidence for the continued deinstitutionalization of marriage (Cherlin 2004).

The Diverging Destinies Perspective

Building on the SDT perspective, which emphasizes the role of ideas in contributing to social change, the diverging destinies thesis (McLanahan 2004) contends that economic and other institutional forces condition the influence of ideational change. Over the past century, our social understandings of marriage increasingly emphasize the importance of romantic love, emotional satisfaction, personal compatibility, self-development, and gender equality instead of procreation and interdependence (Cherlin 2004; Goldscheider and Waite 1991). Achieving these new standards takes resources. For example, successfully negotiating household tasks might benefit from flexible jobs (Gerstel and Clawson 2014). Moreover, finding a compatible partner likely benefits from wide, supportive social networks, which is associated with higher levels of education and majority white racial status (Kao and Joyner 2004; McPherson et al. 2006). Whereas the socially and economically advantaged have the resources to meet these new demands of marriage, the less-educated and minorities may not. Consequently, under the SDT, the socioeconomically disadvantaged experience sharper declines in marriage as well as greater increases in divorce and nonmarital fertility. Building on prior studies showing declines in marriage among cohabitors, this study examines educational and racial/ethnic differences in these declines, focusing on the relationship outcomes of first premarital cohabiting unions. In sum, the SDT theory leads us to expect to see an overall decline in the odds of marriage among more recent cohabiting cohorts, and the diverging destinies perspective predicts that the decline is accompanied by growing differences among cohabitors of different racial/ethnic and educational backgrounds.

Marital Intentions

The SDT and deinstitutionalization of marriage arguments suggest that decreases in the desire to marry are an important contributor to declines in marriage. Consistent with such explanations, a declining proportion of cohabitors intend to marry their partners (Vespa 2014). Minority women and those with lower levels of education are more likely to have experienced single-parent families while growing up (McLanahan and Percheski 2008). Such experiences might reinforce broader ideational changes that lead to weaker attachments to marriage. Even disadvantaged women who have not themselves experienced single-parent families have grown up in contexts with fewer examples of healthy marriage. Consequently, greater declines in marriage among less-educated and minority cohabitors might arise because of their weaker attachment to the institution. If so, we expect that these cohabitors have lower intentions to marry and that this could explain any difference in marriage rates we might observe.

The diverging destinies argument notes that material constraints condition the influence of ideas. Marriage in the United States hinges on couples’ ability to establish an independent household above some culturally acceptable level, which involves stable employment, persistent sources of income, and the ability to ensure long-term financial stability (Gibson-Davis et al. 2005; Smock et al. 2005). Thus, differences in marriage might not be due to lower attachment to marriage but rather to differences in their ability to achieve the material and social requirements of acceptable marriage. Less-educated women might have similar intentions to marry their cohabiting partner as more highly educated women.

Prior studies on marital intentions or marital expectations—a proxy of marital intentions but with a weaker link to marital behavior than intentions (Manning and Smock 2002)—have predominantly focused on racial/ethnic differences rather than educational differences, likely because of the more substantial decline in marriage among African Americans. These studies, however, have produced inconsistent findings. Manning and Smock (2002) found that African American female cohabitors are less likely to expect to marry their cohabiting partners compared with their non-Hispanic white counterparts, whereas Guzzo (2009) suggested that African American female as well as male cohabitors are more likely to report being engaged or having a definite plan for marriage at the start of union than their non-Hispanic white counterparts. Brown (2000) found no racial/ethnic differences among cohabitors in reporting having marriage plans (also see Brown and Booth 1996; Bumpass et al. 1991).

Additionally, some scholars have speculated that racial differences with respect to marital intentions might lie in non-Hispanic white cohabitors’ greater ability to carry out their plans for marriage when compared with African American and other racial/ethnic groups. Findings from previous studies are also mixed. Specifically, although Brown (2000) showed that African American cohabitors with marital plans had 85 % lower odds of marrying their partners than non-Hispanic white cohabitors with a marriage plan, Guzzo (2009) found that the effect of marital intention on the odds of transitioning to marriage does not differ between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites.

The inconsistencies in these past findings likely originate from differences in the measurement (i.e., engagement, marriage plan, marriage expectation), analytic samples (i.e., all cohabitations, first premarital cohabitations), the timing at which marital intentions or expectations were measured (i.e., at the start of union or at the moment of interviewing), and birth cohorts of cohabitors. In our analysis of marital intention, we focus only on the first premarital cohabitations that were initiated in recent years between 2005 and 2010 and operationalize marriage intentions as (retrospectively reported) engagement status at the start of cohabiting unions.

Altogether, our analyses address two research questions. First, are racial/ethnic and educational differences in the outcomes of cohabiting unions growing? Second, are differences in cohabitation outcomes explained by lower intentions to marry among the disadvantaged? If we find evidence of educational and/or racial/ethnic divergence, and differences cannot be explained by marriage intentions, this suggests that ideational accounts of changes in cohabitation miss an important source of family change.

Data and Methods

Data for the analysis are from the National Study of Family Growth 1995 (NSFG Cycle 5) and 2006–2010 (NSFG 2006–2010). Interviewing for the NSFG Cycle 5 was conducted in January through October of 1995. In-person interviews were conducted with a nationally representative sample of 10,847 women 15–44 years of age, of all marital statuses. Interviewing for the 2006–2010 NSFG was conducted from June 2006 through June 2010. In-person interviews were conducted with a nationally representative sample of 12,279 women 15–44 years of age and a nationally representative sample of 10,403 men 15–44 years of age, of all marital status.

Although the NSFG 2006–2010 collected information from both men and women, because the NSFG 1995 provides information on only women, in this study we only use female respondents’ information from both surveys. We also limit our samples to those first premarital cohabitations that were initiated no more than five years prior to the interviews. We observe relationship outcomes of first premarital cohabitations that were initiated in two periods: between 1990 and 1995, and between 2005 and 2010. We restrict the sample to first premarital cohabitations. This restriction likely produces conservative estimates of educational and racial/ethnic differences in cohabitation outcomes: disadvantaged individuals are more likely to have second- and higher-order cohabitations, and these unions tend to be less stable and less likely to result in marriage than first cohabitations (Lichter and Qian 2008). We also exclude 30 premarital cohabitations that last for less than one month from the analytic sample because such a short coresidential arrangement is more ambiguous in its status as a union. Our samples comprise 929 premarital cohabitations initiated between 1990 and 1995, and 1,142 initiated between 2005 and 2010.

Samples

Table 1 displays descriptive information for the analytic samples of cohabiting relationships, from the NSFG 1995 and NSFG 2006–2010, respectively, in comparison with the original full samples from which they are extracted. The two analytic samples are rather similar to the original NSFG samples from which they are drawn with respect to racial/ethnic and educational compositions. The analytic samples of first-time, never-married cohabitors have a median age of 23 at the time of interview, which is younger than the full NSFG samples. The median age at cohabitation is 21 years for both analytic samples. In the analytic sample of first premarital cohabitations initiated between 1990 and 1995, 340 marriages occurred, 347 cohabiting couples broke up, and 242 stayed together at the time of interview; the corresponding figures in the sample of cohabitations initiated between 2005 and 2010 are 194, 504, and 444.

Measures

We construct educational groups as those with less than high school diploma, a high school diploma, some college, and college or more. Racial/ethnic groups in the analysis include non-Hispanic whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and other non-Hispanic racial/ethnic groups. We construct measures that indicate the relationship outcome of the union as the dependent variable with three mutually exclusive categories (marriage, separation, and stay intact).

We measure marital intention with a dichotomous variable based on female cohabiting respondents’ answer to the question: “At the time you began living together, were you and your partner engaged to be married or have definite plans to get married?” from the NSFG 2006–2010 data set. This measure is based on respondents’ retrospective reports and may not be completely accurate. We return to this concern in the discussion. In the analysis, we control for information on duration of union and cohabitor’s age at union initiation (and its squared term) because these two factors are associated with cohabitors’ union outcomes (Brown 2003; Cohen and Manning 2010; King and Scott 2005; Stanley et al. 2006) and may vary by race/ethnicity and education (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008; Manning et al. 2014).

Empirical Strategy

First, we convert data into person-month data sets, with the first month indicating the month when cohabitation started and the last month signaling the month when cohabitation was ended either by marriage or separation or the month when the interview was conducted for those whose first premarital cohabitation remained intact at the time of interview (i.e., censoring). Then, we estimate multivariate discrete-time event history models with multinomial logistic regression to investigate how educational disparities in the odds of transitioning to marriage and the odds of separation, as opposed to staying cohabiting, differ between the two cohabiting cohorts. Second, focusing on recent female cohabitors, we demonstrate whether and how marital intentions vary across racial/ethnic and educational groups. Then, employing multivariate multinomial logistic models, we investigate whether controlling for marital intentions attenuates the racial/ethnic and educational differences in cohabitors’ union transition behavior.

Results

Trends of Educational and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Union Transitions

Multidecrement life table estimates (available upon request) show that among cohabitations initiated between 1990 and 1995, 41 % of cohabiting unions transitioned to marriage, and 35 % separated by the end of the third year following union formation; among the 2005–2010 cohabiting cohort, only 24 % transitioned to marriage, but 41 % dissolved within three years. The results are consistent with findings from prior studies indicating a decline in the probabilities of transitioning to marriage among more recent cohabiting cohorts (e.g., Guzzo 2014; Kennedy and Bumpass 2008, 2011; Manning 2010).

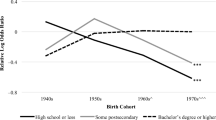

Table 2 displays the results from multinomial logistic regression analysis to statistically test the significance of changes in racial/ethnic and educational disparities. Model 1 includes interactions between education and period, and thus the main education coefficients represent differences in 1990–1995. These education coefficients are not significant, indicating no educational differences in the likelihood of marriage versus remaining cohabiting in the earlier period. The significant coefficients for the interaction between education and period indicate that educational differences increased significantly.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the growing educational disparities. This figure presents the average estimated probability of transitioning to marriage in a given year for each educational group from 1990–1995 and 2005–2010 cohabiting cohorts. For college-educated cohabitors from the 1990–1995 cohort, the average probability of transitioning into marriage in any given year is about 27 percentage points; for the college-educated cohabitors from the 2005–2010 cohort, it is 24 percentage points—an insignificant decline. Additionally, the overlapping confidence intervals of all educational groups in the 1990–1995 cohort indicate that there are no significant educational disparities in transitioning to marriage in this early period. However, educational disparities in the probabilities of transitioning to marriage have become statistically significant among the 2005–2010 cohabiting cohort due to drastic drops in the probabilities of transitioning to marriage among all non-college-educated cohabitors in the recent cohabiting cohort. The average annual probabilities of transitioning to marriage for the 2005–2010 non-college-educated cohabitors are less than one-half of those for their similarly educated counterparts in the early cohort.

In Table 2, Model 2 shows the results for the interaction between race/ethnicity and period. The main effects of race/ethnicity show the results for the 1990–1995 cohabiting cohort. African Americans who initiated the unions in 1990–1995, compared with their non-Hispanic white counterparts, have lower odds of transitioning to marriage but have higher odds of breaking up. The product terms between race/ethnicity and period indicate that differences in union outcomes between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites did not significantly change over time. In fact, the direction of the coefficient suggests that differences between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites might have declined slightly for the recent cohort. An analysis using data from only the more recent period shows no significant racial/ethnic differences in cohabitation outcomes.

Marital Intention and Differences in Union Transitions

Our study suggests that union transition pattern among cohabitors in the recent cohabiting cohort is significantly contingent on cohabitors’ educational attainment. Does accounting for marital intention help attenuate the educational disparities in union transitions among cohabitors from the 2005–2010 cohabiting cohort? Results displayed in Table 3 show that college-educated cohabitors are no more likely than their less-educated peers to enter cohabiting unions engaged or with a definite plan for marriage despite the fact that they were, on average, older than their lower-educated peers at the start of union. That is, cohabitors with less than a high school diploma entered their unions at an average age as young as 19, yet 42 % of them were engaged at the start of union, which is no smaller than that for the college-educated cohabitors (43 %), although the latter entered the union at an average age of 25. Also, there are no significant differences in marital intentions by cohabitors’ race/ethnicity. Specifically, 45 % of African American and non-Hispanic cohabitors reported being engaged at the start of union.

The estimates of the average marginal effects (AME) on union transitions from the multivariate multinomial logistic regression models also show that although marital intention is positively associated with the probability of transitioning to marriage and negatively associated with the probability of relationship dissolution, controlling for marital intention does not attenuate the educational (or racial/ethnic) differences in union transition patterns of recent cohabitors (results not shown, available upon request). Figure 2 displays the predicted probability of transitioning into marriage for educational and racial/ethnic groups, with marital intention controlled. Figure 2 shows that, on average, compared with their similarly educated counterparts (or peers from the same racial/ethnic background) without marital intentions, cohabitors with marital intentions have higher probabilities of transitioning to marriage. Yet, with marital intention controlled, the predicted probability of transitioning into marriage for college-educated women is still significantly higher than that for less-educated women.

95% confidence intervals of predicted average probability of transitioning to marriage in a given month for 2005–2010 cohabiting cohort by education (or race/ethnicity) and marital intention status (weighted results). Racial/ethnic differences in the probability of transitioning into marriage for 2005–2010 cohabiting cohort are not statistically significant before taking into account marital intention (results from multinomial logistic models are available upon request)

Conclusions

Focusing on union transition experience of first premarital cohabitations in two periods, 1990–1995 and 2005–2010, we first examined whether trends in educational and racial/ethnic disparities in cohabitation outcomes—transitioning into marriage (or breaking up)—have become larger over time. Our findings conform to predictions from the SDT perspective as well as the diverging destinies thesis. In line with the SDT perspective and findings from previous studies (e.g., Kennedy and Bumpass 2008), the results of current analysis suggest that cohabitors have increasingly become less likely to progress to marriage. Following the diverging destinies prediction, the current analysis shows that educational disparities in the odds of transitioning into marriage have become larger over time, primarily the result of sharp declines in marriage among cohabitors with some college or a high school diploma in the recent period. Moreover, casting doubt on a purely ideational explanation for these trends, we find no educational (or racial) differences in the marriage intentions of cohabitors.

Americans without a college degree have experienced real declines in earnings and rises in unemployment since the 1970s, when the U.S. economy began to move toward globalization in product, capital, and labor markets (Cherlin 2014; Kalleberg 2011; Levy 1998; Marshall and Tucker 1992; Reich 2002; Sweet and Meiksins 2008). The massive reduction of manufacturing jobs in the American economy largely eliminated an important means for those who do not have college degrees to maintain stable employment and consistently earn wages sufficient to support a family securely above the poverty line (also see Kalleberg 2011; Sweet and Meiksins 2008). As career success and the ability to provide for the family have become greatly dependent on the attainment of a college or graduate degree, many scholars (e.g., Cherlin 2014; McLanahan 2004; Oppenheimer 2003) have linked contemporary variation in family behavior to employment, earnings, and other resources that are stratified by educational attainment. The findings of the current analysis add to the body of research indicating that contemporary family changes are, at least in the short term, considerably related to economic opportunity. Notably, it is possible that the growing educational variation we observed could be due to educational differences in, for example, family-related values and attitudes that undermine trust between men and women and the attachment to marriage. Future research should further investigate educational differences in a broader spectrum of family-related attitudes among cohabitors. Our analyses were unable to detect educational variation in the one attitudinal measure we were able to evaluate with the NSFG.

Admittedly, our retrospective measure of marriage intentions is likely flawed. Cohabitors whose unions dissolve may remember their marriage intentions as lower than they really were at the start of their cohabiting union, and cohabitors who marry may tend to remember their marriage intentions as higher. The cohabiting unions of African Americans and the less-educated are more likely to dissolve than those of non-Hispanic whites and the college-educated. Thus, we believe that retrospective reports of marriage intentions are downwardly biased for African Americans and the less-educated relative to whites and the college-educated. Yet, despite this bias, we found that there are no educational or racial/ethnic differences in marital intentions at the start of union, thus supporting the idea that the lower rates of transition into marriage among disadvantaged cohabitors are not due to a weaker attachment to marriage.

Even though the current analysis shows that racial/ethnic disparities in union outcomes did not change significantly, it would be reckless to conclude that the significance of race in family behavior has declined. Rather, it may be that disadvantaged African Americans are unable even to form cohabiting unions today due to mass imprisonment and other factors that reduce the number of available men. Recent research shows that while nearly two-thirds of white nonmarital births occur to cohabiting women, only 37 % of African American nonmarital births occur to mothers living with the father (Lichter et al. 2014). Future research should examine racial/ethnic variation in patterns of union formation, especially among the most disadvantaged.

Overall, the results of this study indicate that SDT accounts of family change are incomplete. We argue that declines in marriage (at least recently) are the result of rising standards for marriage in the context of substantial economic and social inequality. We observed no decline in the likelihood that college-educated women’s cohabiting union transitioned into marriage. Moreover, the changes in outcomes of cohabiting unions of less-educated women are not obviously linked to declines in marriage intentions. By stressing the importance of structural barriers in preventing some people from securing resources for stable family life, the diverging destinies thesis provides valuable insights into declines in marriage among cohabitors. As the marriage has become optional and the standards for marriage have risen, those on the lower half of the socioeconomic spectrum are finding it difficult to meet these standards.

References

Brown, S. L. (2000). Union transitions among cohabitors: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 833–846.

Brown, S. L. (2003). Relationship quality dynamics of cohabiting unions. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 583–601.

Brown, S. L., & Booth, A. (1996). Cohabitation versus marriage: A comparison of relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 668–678.

Bumpass, L. L., Sweet, J. A., & Cherlin, A. J. (1991). The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 913–927.

Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861.

Cherlin, A. J. (2014). Labor’s love lost: The rise and fall of the working-class family in America. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cohen, J., & Manning, W. (2010). The relationship context of premarital serial cohabitation. Social Science Research, 39, 766–776.

Ellwood, D. T., & Jencks, C. (2004). The spread of single-parent families in the United States since 1960 (Faculty Research Working Papers Series No. RWP04-008). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Gerstel, N., & Clawson, D. (2014). Class advantage and the gender divide: Flexibility on the job and at home. American Journal of Sociology, 120, 395–431.

Gibson-Davis, C. M., Edin, K., & McLanahan, S. (2005). High hopes but even higher expectations: The retreat from marriage among low-income couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1301–1312.

Goldscheider, F. K., & Waite, L. J. (1991). New families, no families? The transformation of the American home. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goldstein, J. R., & Kenney, C. T. (2001). Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review, 66, 506–519.

Guzzo, K. B. (2009). Marital intentions and the stability of first cohabitations. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 179–205.

Guzzo, K. B. (2014). Trends in cohabitation outcomes: Compositional changes and engagement among never-married young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 826–842.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2011). Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s–2000s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kao, G., & Joyner, K. (2004). Do race and ethnicity matter among friends? Sociological Quarterly, 45, 557–573.

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. L. (2008). Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19(article 47), 1663–1692. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.47

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. L. (2011, March–April). Cohabitation and trends in the structure and stability of children’s family lives. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Washington, DC.

King, V., & Scott, M. E. (2005). A comparison of cohabiting relationships among older and younger adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 271–285.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1995). The second demographic transition in Western countries: An interpretation. In K. O. Mason & A.-M. Jenson (Eds.), Gender and family change in industrialized countries (pp. 17–62). New York, NY: Oxford University Press Inc.

Lesthaeghe, R. J., & Neidert, L. (2006). The second demographic transition in the United States: Exception or textbook example? Population and Development Review, 32, 669–698.

Lesthaeghe, R. J., & van de Kaa, D. (1986). Twee demografische transities? [Two demographic transitions?] In R. J. Lesthaeghe & D. van de Kaa (Eds.), Bevolking: Groei en krimp [Population: Growth and shrinkage] (pp. 9–24). Deventer, The Netherlands: Van Loghum Slaterus.

Levy, F. (1998). The new dollars and dreams: American incomes in the late 1990s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lichter, D. T., & Qian, Z. (2008). Serial cohabitation and the marital life course. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 861–878.

Lichter, D. T., Sassler, S., & Turner, R. N. (2014). Cohabitation, post-conception unions, and the rise in nonmarital fertility. Social Science Research, 47, 134–147.

Manning, W. D. (2010). Trends in cohabitation: Twenty years of change, 1987–2008 (NCFMR Family Profiles report). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University.

Manning, W. D., Brown, S. L., & Payne, K. K. (2014). Two decades of stability and change in age at first union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 247–260.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (1995). Why marry? Race and the transition to marriage among cohabitors. Demography, 32, 509–520.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2002). First comes cohabitation and then comes marriage? A research note. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 1065–1087.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2005). Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 989–1002.

Marshall, R., & Tucker, M. (1992). Thinking for a living: Work, skills, and the future of the American economy. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Martin, S. P. (2006). Trends in marital dissolution by women’s education in the United States. Demographic Research, 15(article 20), 537–560. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.20

Martin, S. P., Astone, N. M., & Peters, H. E. (2014). Fewer marriages, more divergence: Marriage projections for millennials to age 40 (Urban Institute research report). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Brashears, M. E. (2006). Social isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades. American Sociological Review, 71, 353–375.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (2003). Cohabiting and marriage during young men’s career-development process. Demography, 40, 127–149.

Raley, R. K., & Bumpass, L. L. (2003). The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research, 8(article 8), 245–260. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2003.8.8

Reich, R. B. (2002). The future of success: Working and living in the new economy. New York, NY: Vintage.

Smock, P. J., Manning, W. D., & Porter, M. (2005). “Everything’s there except money”: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 680–696.

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Markman, H. J. (2006). Sliding versus deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations, 55, 499–509.

Sweet, S., & Meiksins, P. (2008). Changing contours of work: Jobs and opportunities in the new economy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, Sage Publications.

van de Kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42(1), 1–59.

Vespa, J. (2014). Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 207–217.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this research was previously presented at the 2014 meeting of the Population Association of America. We are grateful for helpful comments and suggestions by participants in the PAA session. This research was supported by grant, 5 R24HD042849, Population Research Center, and 5 T32HD007081, Training Program in Population Studies, awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Opinions reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuo, J.CL., Raley, R.K. Diverging Patterns of Union Transition Among Cohabitors by Race/Ethnicity and Education: Trends and Marital Intentions in the United States. Demography 53, 921–935 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0483-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0483-9