Abstract

We use more than 20 years of data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 to examine wealth trajectories among mothers following a nonmarital first birth. We compare wealth according to union type and union stability, and we distinguish partners by biological parentage of the firstborn child. Net of controls for education, race/ethnicity, and family background, single mothers who enter into stable marriages with either a biological father or stepfather experience significant wealth advantages over time (more than $2,500 per year) relative to those who marry and divorce, cohabit, or remain unpartnered. Sensitivity analyses adjusting for unequal selection into marriage support these findings and demonstrate that race (but not ethnicity) and age at first birth structure mothers’ access to later marriage. We conclude that not all single mothers have equal access to marriage; however, marriage, union stability, and paternity have distinct roles for wealth accumulation following a nonmarital birth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nonmarital births have long been a concern for both policy-makers and scholars because women whose births occur outside of marriage have higher rates of poverty and persistent unemployment (Frech and Damaske 2012; McLanahan and Percheski 2008). As a result, children raised in these households experience poorer outcomes, primarily as a result of their socioeconomic disadvantages relative to children born to married parents (Amato 2005; McLanahan and Percheski 2008; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994). Although much is known about predictors of single motherhood (Upchurch et al. 2002), the relationships between single-parent households and child well-being (Amato 2005; McLanahan and Percheski 2008; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994), and variation in these relationships according to race/ethnicity or child characteristics (see the review by McLanahan and Percheski 2008), far less is known about long-term aspects of financial well-being for mothers following a nonmarital first birth. This study addresses this significant gap in existing knowledge about single mothers as they complete childbearing and age into their prime earning years by studying the wealth trajectories of women with a nonmarital first birth, and by comparing mothers based on their subsequent union formation, union stability, and paternity status of the partner.

Extending scholars’ knowledge of the relationships between union formation, union stability, partner paternity, and wealth attainment among women with a nonmarital first birth is important for three reasons. First, most mothers with a nonmarital first birth do not remain single throughout adulthood (Bzostek et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2011) and their subsequent union formation patterns may shape the magnitude of the negative outcomes typically associated with nonmarital childbearing. For example, women with a nonmarital first birth who later transition into an enduring marriage may be less affected by many of the negative economic, health, and psychological well-being outcomes that are associated with nonmarital childbearing (Johnson and Favreault 2004; Lichter et al. 2003; Williams et al. 2011). Second, although women’s access to economic resources and ability to accumulate them change over the life cycle (see Hao 1996; Wilmoth and Koso 2002), no prior studies have examined long-term change in the wealth of single mothers. If mothers are saving (or conversely, accruing debt), these economic behaviors will not be captured by measures commonly used to measure single mothers’ socioeconomic status, such as income, education, or employment status (see, e.g., McLanahan and Percheski 2008). Finally, few studies have capitalized on panel data that allow for a detailed, longitudinal observation of single mothers from early adulthood into middle age and no study has used more than two decades of panel data. Following single mothers over time, especially into middle age as mothers form and dissolve unions, provides insight into how different configurations of family structure affect long-term financial well-being.

We study wealth accumulation among women with a nonmarital first birth and identify different trajectories of wealth according to women’s later union transitions: whether women marry or cohabit (union formation), whether the relationship lasts (union stability), and whom they marry (paternity). We contribute to existing research on the financial consequences of nonmarital fertility and the links between the union characteristics and economic well-being of single mothers by describing (1) how the wealth of single mothers varies during young adulthood and over time as they enter into middle age, and (2) how wealth attainment varies among women who experienced a nonmarital first birth according to their subsequent union formation, union stability, and paternity status of their partner.

Background

Marriage and Wealth Accumulation Following a Nonmarital Birth

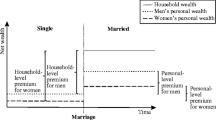

The positive relationship between marriage and wealth accumulation is well established (Hirschl et al. 2003; Painter and Vespa 2012; Ulker 2009; Vespa and Painter 2011; Wilmoth and Koso 2002). The married benefit from economies of scale, wage premiums, financial transfers, and the potential for dual incomes (Cohen 2002; Hao 1996; Ulker 2009; Waite 1995). Married individuals also benefit from expectations of permanence, legal and cultural parameters of the union, and numerous other codified advantages that may contribute to greater trust and commitment, thereby helping couples feel secure in making long-term financial investments together (Cherlin 2004; Heimdal and Houseknecht 2003; Pollak 1985).

Those who marry also differ from those who do not, and many of the characteristics distinguishing the married from the nonmarried are associated with greater wealth-earning capacity. Increasing marital homogamy, particularly among college-educated spouses in dual-earner households, contributes to wealth disparities between the married and nonmarried by concentrating high-skilled earners in the same households (Schwartz and Mare 2005). Single mothers have fewer opportunities to form these financially advantageous unions relative to women who were childless upon marrying. Unmarried mothers are also less educated, on average, than women whose first births occur within marriage (Upchurch et al. 2002), and they face more-restrictive marriage markets in which potential spouses have less education and less-stable employment (Harknett and McLanahan 2004). Thus, not only is marriage less likely for single mothers, but it is also potentially less likely to be a wealth-building union than it is for women who marry without children. Further, single mothers face greater odds of divorce than mothers whose children are born within marriage, and marital disruption is independently associated with financial instability (Cherlin 2010; Lichter et al. 2003; Smock et al. 1999; Williams et al. 2008). Thus, despite the clear wealth benefits of marriage, the unique barriers to good marital prospects faced by single mothers and the greater instability of these marriages lead us to expect that marriage may not offer the same wealth benefits to mothers who have experienced nonmarital fertility (Painter and Shafer 2011; Painter and Vespa 2012; Vespa and Painter 2011). At the same time, given the clear socioeconomic disadvantages associated with nonmarital childbearing, we expect that single mothers who marry will report higher rates of wealth accumulation than those who do not.

Cohabitation and Wealth Accumulation Following a Nonmarital Birth

Women with nonmarital births are more likely to cohabit than to marry (Qian et al. 2005), which may be partly responsible for single mothers’ limited wealth accumulation on average. Compared with marriage, cohabiting unions are less stable, shorter, and less commonly characterized by norms to pool finances, restricting a cohabiting couple’s ability to make long-term shared investments (Qian et al. 2005; Manning and Brown 2006). Cohabiting couples are also, on average, less educated and report lower incomes than the married (Smock 2000), and many couples form cohabiting unions out of financial need rather than as a step toward marriage (Sassler 2004; Sassler and Miller 2011). In addition, although the earnings potential of a new cohabiting partner may be greater than that of the biological father (see Bzostek et al. 2012), single mothers’ new partners are, on average, less educated than partners of women who enter into unions without children (Qian et al. 2005), indicating that a single mother may remain disadvantaged even after forming a cohabiting union. This leads us to expect that cohabiting unions are less conducive to wealth building than marriage following a nonmarital birth, even after adjusting for the shorter duration of these unions and compositional differences between those who marry and those who cohabit.

Cohabiting mothers may, however, report greater rates of wealth accumulation than women who remain continually unpartnered, even if the cohabiting unions do not transition to marriage. Cohabiting mothers have access to financial and nonfinancial resources that may promote savings and wealth accumulation, including financial contributions from the cohabiting partner for household expenses (i.e., economies of scale) and/or childcare assistance from social fathers (Berger et al. 2008). Evidence also indicates that single mothers have high standards for the economic prospects of new coresidential partners (Bzostek et al. 2012); therefore, single mothers may be unlikely to enter cohabiting unions unless their partner can contribute financially to the household. As such, we expect that single mothers who enter cohabiting unions will experience greater rates of wealth accumulation than single mothers who remain unpartnered following a nonmarital first birth, even if these cohabiting unions do not transition to marriage.

Union Stability and Wealth

The negative relationships between union dissolution and financial status—generally measured as risk of poverty and change in household income—are well established and extend across both cohabitation and marriage for women, beginning prior to the union and in some cases extending past a later repartnering (Lichter et al. 2003; Osborne et al. 2007; Smock et al. 1999). Although remarriages are associated with economic benefits (Ozawa and Yoon 2002), remarriage is less likely among single mothers relative to women who were childless upon marrying (Bramlett and Mosher 2002; Graefe and Lichter 1999; Williams et al. 2008). For women with a nonmarital birth, divorce appears to pose a greater financial risk relative to women who were childless prior to marriage (Lichter et al. 2003), suggesting that even if single mothers benefit financially from marriage, they will experience a greater penalty for a subsequent divorce. As such, we propose that women with a nonmarital birth who later form stable marriages will report greater gains in wealth over time than peers who do not form residential unions, but that those who marry but later divorce will experience a diminished wealth benefit relative to those remaining in intact unions, regardless of whether they remarry.

Paternity, Union Status, and Wealth

The paternity status of a partner may also influence wealth accumulation, as biological fathers transfer larger and more frequent sums to their biological children relative to stepchildren (Pezzin and Schone 1999). Additional evidence indicates that the presence of a biological father is associated with reduced material hardship among single mothers relative to the financial benefits provided by a social father (Osborne et al. 2007). As such, we compare unions based not only on whether they are cohabiting or marital unions, but also by the paternity status of the father of the firstborn child. Because they are investing directly in their biological child, we may observe a wealth premium for mothers who are living with or married to the biological father compared to a stepfather or social father.

Yet, when scholars disentangle paternity, coresidence, and union type, it appears that marriage—and not paternity—is the primary determinant of a family’s union and/or income stability (Brown 2004; Hofferth 2006; Hofferth and Anderson 2003; Manning and Brown 2006; Osborne et al. 2007; Smock and Greenland 2010). This leads us to expect that marriage to either the biological father or to a stepfather will be associated with greater wealth accumulation than remaining unpartnered. Cohabiting unions—even with the biological father—are less stable than marriages, less likely to be associated with wealth transfers from the biological father’s family, and less likely to include biological fathers who are employed or have high income relative to married biological-parent households (Brown 2004; Hao 1996; Manning and Brown 2006). Married stepparent families fare better economically than cohabiting biological parent households but are often economically worse off than married biological-parent families (Brown 2004, 2010; Hohmann-Marriott 2011; Manning and Brown 2006). In part, this may be because, unlike biological married fathers, stepfathers do not experience a wage premium upon marrying (Killewald 2013). In sum, although we acknowledge that the presence or involvement of a biological father is beneficial for children’s behavioral and emotional outcomes (Berger et al. 2008; Bzostek 2008), we propose that living with a biological father will be associated with greater rates of wealth accumulation for single mothers who later marry but not for those who cohabit. Further, we expect that stable marriages to a biological father will be associated with greater rates of wealth accumulation than stable marriages to a stepfather.

Union stability also influences the wealth accumulation of a married family over time. Unions involving stepchildren are more likely to dissolve, and stepfathers with children in other households may have to devote financial and nonfinancial resources to nonresidential children (Hofferth 2006; Hofferth and Anderson 2003). In line with our previously outlined expectations, we propose that intact marriages to the biological father will be associated with the greatest wealth accumulation, followed by intact marriages to stepfathers, and then followed by marriages ending in dissolution.

Selection Into Unions

Previous research has established that single mothers are less likely than childless women to ever marry (Bennett et al. 1995; Lichter et al. 2003). Among single mothers, non-Latina black women, economically disadvantaged women, and women with a greater age at first birth are least likely to ever marry (Bennett et al. 1995; Lichter, et al. 2003). These factors are also associated with wealth accumulation: race/ethnicity, poverty, marital and cohabitation history, timing of childbearing, and number of children are each associated with wealth accumulation across adulthood (e.g., Addo and Lichter 2013; Conley 1999; Keister 2000, 2004; Oliver and Shapiro 2006; Painter and Shafer 2011; Painter and Vespa 2012; Vespa and Painter 2011). These and other factors are important to account for in our study. As a final expectation, we propose that, net of selection, marriages—especially stable marriages to a biological father—will be associated with greater wealth at midlife relative to remaining unpartnered.

Method

Data and Sample

To estimate the wealth trajectories of women with a nonmarital first birth, we used the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), a longitudinal study of a nationally representative U.S. cohort born between 1957 and 1964. Respondents were interviewed annually from 1979 until 1994, and biennially thereafter. Mothers provided full fertility and union histories beginning with the baseline interview in 1979. This information was updated with each additional wave (through 2004 for this study, when all mothers turned 40 and children were likely to still be living in the household). Questions assessing wealth attainment were first asked in 1985 when the sample was 20–27 years old; these questions were consistently asked through the most recent round of data collection.

To evaluate the wealth trajectories of women who experienced a nonmarital birth, we include in our sample never-married “single” mothers. These 1,131 women were never-married at the time of their first birth, were not part of the oversamples that were discontinued after 1984, and were not missing information on their union status at or near age 40. This last sample restriction excluded 121 mothers from our sample.Footnote 1 Each woman in our sample contributed data on wealth between 1985 (the first year of wealth data) and 2004 (the round of data when the youngest respondents turned 40), resulting in 16,965 person-years of data on wealth and other time-varying variables.

Outcome Variable

The outcome variable is net worth (value of assets less debts), in thousands.Footnote 2 Assets include the value of financial investments, such as checking and savings accounts, retirement accounts, and stocks, as well as the value of nonfinancial holdings, such as homes, automobiles, and other valuable possessions. We weighed the value of these assets against total debts (credit cards, hospitals bills, student loans, mortgages, and liens).

Explanatory Variables

Union Histories

We identified and compared five configurations of mothers’ unions following a nonmarital birth to examine how union formation, union stability, and partner paternity are related to single mothers’ wealth accumulation. First, to assess the effect of simple union formation, we compared mothers who ever married, ever cohabited, or remained single (reference category) following a nonmarital birth. Second, we assessed cohabitation history with four mutually exclusive categories: women who neither cohabited nor married (reference), women who cohabitated but never married, women who lived with and eventually married their cohabiting partner (spousal cohabitation), and women who married but did not cohabit with their spouse prior to marriage. Third, for union stability, we assessed the intactness of marriage at age 40: intact first marriage, intact second or third marriage, and separated/divorced compared with the continually never-married. Fourth, we incorporated paternity status of the partner, including whether single mothers married or cohabited with the biological father of their child or a stepfather, or remained continually unpartnered (reference).

Last, we assessed union formation, union stability, and paternity status together. Table 1 details the variables for mothers’ union histories between their first births and age 40. This table shows that one-third of this sample never married, including our reference category of single mothers who neither cohabited nor married (17 % of our sample of single mothers; n = 190), never-married women who cohabited with the biological father of their first child (and may have had other cohabiting partners) (11 %; n = 127), and never-married women who cohabited with one or more stepfathers but not the biological father (6 %; n = 67). Two-thirds of the women married, with almost one-quarter (n = 266) of single mothers reporting an intact marriage to the biological father at age 40. Of the remaining women, 13 % (n = 146) married the biological father but divorced by age 40 (these women may have later remarried); 17 % (n = 197) married a different partner and remained married by age 40; and 12 % (n = 138) married a different partner and divorced by age 40 (these women may have later remarried another stepfather). Thus, our sample allowed for sufficient variation and adequate sample size to examine wealth differences across single mothers based on their subsequent union formation and the stability of those unions. Sample size does limit us, however, from further disaggregating categories of women whose marriages end in divorce.

Time

In growth curve analyses, it is important to use a theoretically meaningful variable to measure time. Here, we used women’s age (in years) rather than the NLSY survey year as the unit of time for all analyses. The NLSY sample varied in age from 14 to 22 in 1979, making survey wave an imprecise tool to measure variation in wealth over time across women in the sample. Using age as our time metric, we measured change in wealth over time beginning when mothers were in their 20s and extending through at least age 40. We centered the intercept, or measure of baseline wealth, on age 20, the youngest age for which we had measures of wealth, given that the wealth questions were first asked in 1985.

Union Duration and Age at First Birth

Other explanatory variables included a time-invariant continuous measure for mothers’ age at first birth and two time-invariant continuous measures (in years) of the duration of respondents’ cohabitation and/or marriage spells.

Control Variables

As shown in Table 5 in the appendix, we controlled for respondent and parental background characteristics, including dichotomous variables for race/ethnicity (non-Latina black, Latina, and non-Latina white (reference category)) and a set of dichotomous variables for respondent’s educational attainment, measured at baseline in 1985 (no high school diploma (reference category), high school diploma, some college, or a bachelor’s degree or higher). We also accounted for the respondent’s financial resources, including a time-varying measure of family income (logged in the analyses), the receipt of any inheritance (1 = yes), and the time-varying amount of that inheritance (logged in the analyses). We included a time-varying variable for number of children currently living in the household. We also controlled for several characteristics of respondents’ parents: parental education (highest level among both parents, coded similarly to respondents’ education), employment status (1 = at least one parent worked full-time), and family income (logged in the analyses).

Analytical Strategy

We modeled wealth accumulation using multilevel growth curves (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002; Singer and Willett 2003). Growth curves use a hierarchical specification and nest time (age) within respondents. This method allowed us to estimate associations between time-varying (age) and time-constant (union history) variables and wealth trajectories. Our multilevel growth curves estimated associations between (1) union histories and wealth at the beginning of our observation period in 1985, when wealth was first measured and women were aged 20–28 (other covariates controlled), and (2) union histories and wealth over time as women entered their 40s (other covariates controlled). To correct for heteroskedastic and correlated measurement errors across time, we used robust standard errors and assumed a first-order autoregressive structure. We imputed missing data using the multiple imputation, then deletion (MID) procedure (von Hippel 2007).Footnote 3

We specify five models (Table 3) that followed from our expectations regarding single mothers’ union formation, union stability, and paternity of their partner. Model 1 (simple union formation) compares women who ever married or ever cohabited with those who did not form residential partnerships (marriage and cohabitation categories are not mutually exclusive). Model 2 (cohabitation history) compares mothers who cohabited but did not marry, mothers who cohabited and later married their cohabiting partner (i.e., spousal cohabiters), and mothers who married but did not cohabit with that partner prior to marriage. Model 3 (union stability) compares mothers based on the formation and stability of marital unions following a nonmarital birth. Model 4 (paternity) estimates relationships between wealth and women’s cohabitation and marital histories and adds paternity status, describing whether mothers formed cohabiting or marital unions and whether these unions were with a biological father or stepfather. Model 5 disaggregates women by union formation (cohabitation and marriage), union stability (intact marriage versus divorce), and paternity status (biological father versus stepfather).

In the findings that follow, we report baseline wealth values across single mothers (centered on age 20) but focus our interpretations primarily on differences among single mothers in their change in wealth over time. Changes over time are more clearly indicative of an effect of the characteristics of the union, but the baseline differences may conflate causal order. To aid in making comparisons across groups, we test for equality of coefficients within the same model (Clogg et al. 1995; see also Paternoster et al. 1998) and identify significant differences between explanatory variables both in the text and in Table 3.

We supplement our growth curve analyses with multinomial treatment models to examine whether selection into union configurations at midlife influences wealth attainment (Deb and Trivedi 2006). These models, similar to a Heckman correction, adjust for the unequal selection of some women into marriage and cohabitation following a nonmarital first birth by employing a two-stage strategy that first predicts selection into a union and then, net of selection into a union, estimates associations between union status and wealth. Because multinomial treatment models cannot be applied to a time-varying dependent variable, we used two modified wealth outcomes: total wealth at age 40 (the youngest age for respondents in 2004) and the difference in wealth between age 40 and age 28 (the age of the oldest respondents in 1985, the first year data on wealth are collected). Predicting wealth at age 40 allows us to observe absolute wealth differences across women’s union categories as they enter their prime earning years and complete childbearing. Predicting change in wealth between ages 28 and 40 gives us a within-person measure of change in wealth according to women’s different union configurations that reduces the bias that would be associated with women’s differing baseline levels of wealth.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 contains descriptive statistics for the outcome and explanatory variables (descriptive statistics for the control variables are displayed in Table 5 in the appendix). We return to the means for net worth later. Several variables warrant closer examination. First, because time is central to our analysis of wealth trajectories, we present means and standard deviations for women’s age in 1985 (the beginning of our data) and their age over time. Second, women’s age at first birth varies relatively widely across the union histories. Among women with a nonmarital birth, the oldest women at first birth are those who never married but cohabited with the biological father (23 years), and the youngest are women who married the biological father of their child following a nonmarital birth and later divorced (18.5 years). Third, the average durations of cohabiting unions and marriage for single mothers are relatively short. Single mothers who cohabited with the biological father resided in these unions the longest; women remaining in intact marriages to the biological father cohabited, on average, for the shortest duration.

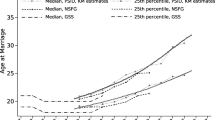

Figure 1 presents means for net worth at both the beginning of our data and over time by union history (Table 1 reports the exact amounts) for women with a nonmarital birth. We note in the figure where either baseline or over-time wealth values are significantly different from the reference category of single mothers who neither cohabited nor married. At baseline, women who later entered an intact marriage with the biological father had the highest baseline wealth ($7,257), followed by women who later married and divorced the biological father ($6,958). Both of these initial values were significantly different from single mothers who never partnered. In contrast, we found no significant difference in baseline wealth between women who cohabited or women who married a stepfather (regardless of the intactness of that relationship) compared with the reference category. Over time, paternity continued to be associated with wealth accumulation: women who married the biological father (regardless of a later divorce) reported the greatest wealth accumulation over time. Following these two groups were women who married a stepfather (regardless of a later divorce) or cohabited with the biological father. The lowest amounts of wealth accumulation over time were observed among women who neither cohabited nor married and women who cohabited with a stepfather, and these wealth values were statistically equivalent; the other categories of union history had higher average wealth over time than women who never partnered. In sum, Fig. 1 provides evidence that the union histories are associated with differential patterns of wealth accumulation and points to both marriage and paternity as important factors in the wealth attainment of single mothers.

Union status differences in baseline wealth and wealth trajectories (in thousands) for women with a nonmarital birth (N = 1,131), NLSY79. An * indicates that the net worth value is significantly different (at p < .05 or better) from either the baseline or over-time value for the reference group of single mothers who never partnered

Regression Results

Results from the growth curve parameter estimates of union histories on wealth accumulation are shown in Table 3. Model 1 presents differences in initial wealth (centered on age 20) and the rate of wealth accumulation over time for single mothers’ simple union formation.Footnote 4 In this model, women who eventually married had a significantly different pattern of wealth accumulation over time than the reference category of women who never cohabited and never married. Baseline wealth values did not significantly differ by either marital or cohabitation experience; however, women who eventually married reported an increase of $2,463 (= $963 + $1,500) in wealth accumulation per year of age, whereas women who neither cohabited nor married had an increase of only $963 in wealth per year of age. In contrast, the pattern of wealth attainment for women who cohabited but did not marry was not statistically different from the reference category. This model provides support for our expectation that marriage—but not cohabitation—is a wealth-enhancing institution because marriage increased the slope of wealth accumulation over time.

Model 2 examines single mothers’ cohabitation histories. At baseline, women who cohabited with their future spouse (i.e., spousal cohabiters) and women who married without spousal cohabitation reported less wealth than those who remained unpartnered. Compared with women who neither cohabited nor married, spousal cohabiters had $9,258 less wealth at baseline, whereas those who married without spousal cohabitation had $5,940 less net worth.Footnote 5 These initial wealth disadvantages eroded over time, however, revealing a marital wealth premium. Women who neither cohabited nor married accumulated wealth at a rate of $1,075 per year of age, but women who eventually married—regardless of spousal cohabitation experience—had a rate of wealth accumulation of $2,523 (= $1,075 + $1,448) (marriage without spousal cohabitation) or $2,820 (= $1,075 + $1,745) (marriage and spousal cohabitation) per year of age.Footnote 6 Women who cohabited and never married had similar wealth at baseline and accumulated wealth over time at a comparable rate as the reference group. In sum, our results showed mixed support for our expectations. We found support for our expectation that cohabitation without marriage would not be associated with greater wealth accumulation relative to remaining unpartnered. Contrary to our expectations, we did not find evidence of a wealth premium for spousal cohabiters: women who lived with a partner prior to marrying that same individual increased their wealth at the same rate over time as women who married without spousal cohabitation.

Model 3 tests the relationship between union stability and wealth accumulation. Compared with the reference group of women who did not marry or cohabit, only women with an intact first marriage reported less wealth ($10,999) at baseline. Over time, continually married ($3,138 = $1,413 + $1,725) and remarried ($3,081 = $1,413 + $1,668) women accumulated wealth at a greater rate than women who never married ($1,413).Footnote 7 It is notable that the model predicts that remarried women have a wealth advantage over time, but does not predict a significant initial wealth disadvantage at baseline. Divorced women who did not remarry had a rate of wealth accumulation similar to that of continually unpartnered women. Overall, these results were contrary to our expectations. We found no evidence of a wealth penalty for remarried women relative to women in an intact first marriage. Divorced women who did not remarry gained wealth at a rate that was indistinguishable from that of never-married women.

Model 4 adds paternity status to our Model 1 test of the relationships between union formation and wealth accumulation. Women who married the biological father ($7,806) or who later married a stepfather ($6,669) had less baseline wealth than their counterparts who remained unpartnered.Footnote 8 Over time, each of these groups reported significantly higher rates of wealth accumulation than unpartnered single mothers. These rates per year of age, in order, were $3,177 (= $635 + $2,542) for women who married the biological father, $2,282 (= $635 + $1,647) for women who married a stepfather, $2,264 (= $635 + $1,629) for women who cohabited with the biological father, and $635 for women who neither cohabited nor married. Equality-of-coefficients tests show that the slopes for these groups are all equivalent. Women who cohabited with a stepfather had baseline wealth and rates of wealth accumulation that were not statistically different from those of the reference category. Together, these findings lend strong support to our expectations that marriage and paternity offer distinct benefits for wealth accumulation.

Finally, Model 5 examines wealth among women with a nonmarital birth, as well as adjusted wealth trajectories according to union formation, union stability, and paternity status of the partner. Two groups had lower wealth at baseline than continually unpartnered single mothers: women with intact marriages to the biological father ($14,030) or to a stepfather ($10,916).Footnote 9 In contrast, five groups differed in their rate of change in wealth over time relative to continually unpartnered women. Notably, consistent with our expectations for marital union stability and paternity, wealth accumulation was highest for women with intact marriages to the biological father ($3,608 = $612 + $2,996); however, the rate of wealth attainment for this group was statistically equivalent to that of single mothers with an intact marriage to the stepfather ($2,665 = $612 + $2,053). Thus, our results suggest that an intact marriage is most conducive to wealth accumulation, regardless of the paternity status of the male partner. With one exception, the other groups had significantly lower rates of wealth accumulation than these two groups but significantly higher rates of wealth accumulation than mothers who never married or cohabited.Footnote 10 Women who cohabited with a stepfather did not accumulate wealth at a significantly higher rate than mothers who never married or cohabited.

Figure 2 graphs predicted values for baseline wealth and wealth accumulation over time between the reference group of single mothers who never cohabited or married and the union histories that display significantly different patterns of wealth attainment (see Model 5, Table 3).Footnote 11 All of the groups displayed in Fig. 2 demonstrate steeper rates of wealth accumulation than the reference group, despite some groups having an initial wealth disadvantage at baseline. One group in particular—women with intact marriages to a biological father—has the greatest wealth accumulation over time, at a rate that pushes their wealth attainment past both the reference category and the other categories of single mothers. Thus, although union formation and union stability are important for wealth accumulation, paternity matters as well.

Selection Into Marriage

Because single mothers who later marry likely share other traits that are associated with wealth accumulation—including cumulative advantages related to race/ethnicity, history of poverty, family of origin characteristics, and timing of first birth—it is important to evaluate the relationships between union status and wealth accumulation following a nonmarital first birth, adjusting for unequal selection into later unions. Table 4 includes estimates from multinomial treatment models of total wealth at age 40 (column A) and the difference in wealth over time (assets at age 40 minus assets at age 28; column B), adjusting for selection into unions and other baseline covariates. Race/ethnicity, age at first birth, respondents’ education and socioeconomic resources, and the respondents’ parental education and socioeconomic resources are included in Panel I, which estimates selection models predicting union status by age 40; these same variables are also included in the second-stage equation (shown in Table 4, Panel II) predicting net worth at age 40 and change in wealth, adjusting for selection into unions.

Panel I of Table 4 displays estimates of the relationships between union status and wealth at age 40 (column A) and the difference between wealth at age 40 and wealth at age 28 (column B), net of baseline covariates associated with selection into unions. Values in columns A and B in Panel I, which estimates selection into unions for each of our outcomes, can be interpreted as multinomial regressions. Positive, significant coefficients indicate a greater likelihood of entering into a given union category relative to remaining continually unpartnered; negative coefficients indicate a reduced likelihood of entering into that union category relative to remaining continually unpartnered. The first-stage models in Panel I predicting union status as a function of baseline characteristics show that, consistent with previous research, non-Latina black women and women with later ages at first birth were less likely to marry following a nonmarital birth. Other variables, such as education and income of the mother and her family of origin, were less consistently associated with union formation and stability.

Columns A and B of Panel II predict wealth at age 40 and the difference in wealth across ages 28–40, adjusting for Panel I estimates of unequal selection into unions following a nonmarital first birth. Net of selection, the coefficient in column A for wealth at age 40 shows that women in stable marriages to either a biological father or a stepfather reported greater wealth than women who remained continually unpartnered. Column B of Panel II shows that the difference in wealth was also greater (i.e., these women accrued more wealth between ages 28 and 40) when they were able to form stable marriages to a biological father or stepfather relative to remaining continually single, net of selection. Other union configurations—including cohabitation and marriages that end in divorce to either a biological father or to a stepfather—were not associated with greater wealth at midlife or change in wealth relative to remaining continually unpartnered, after adjusting for baseline characteristics that select women into these unions. In sum, although the growth curve estimates in Table 3 suggest that all marital unions (to a biological father or stepfather, regardless of later dissolution) provided wealth premiums to single mothers when compared with remaining unpartnered, after we accounted for selection, only enduring marriages to a biological father or a stepfather appear to have provided long-term wealth benefits.

Discussion

Efforts to understand the economic disadvantages associated with nonmarital fertility have often treated single mothers as a homogeneous group—one that is created with a nonmarital birth and experiences continual economic disadvantage regardless of later union transitions. Partly as a result of this assumption, single mothers and their children are often thought to be economically impoverished throughout their lives and lacking in stable social ties relative to married mothers (Amato 2005; McLanahan and Percheski 2008; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994). Our study challenges this assumption by assessing how wealth trajectories among women who had a nonmarital birth vary over a period of nearly 20 years as a function of their diverse marital and cohabiting experiences.

We found evidence of substantial heterogeneity in both union configurations and trajectories of wealth accumulation through age 40. Most women build wealth following a nonmarital birth, but the amount varies widely based on the types of unions they later form, the stability of these unions, and the paternity status of the partner. Indeed, union formation, union stability, and paternity of the partner each carry distinct wealth premiums. Both our growth curve (Table 3) and multinomial treatment models (Table 4) found that, compared with remaining continually unpartnered, later marriages were associated with greater rates of wealth accumulation following a nonmarital birth. However, our selection models showed that for women who formed marriages that later ended in divorce, including marriages to a biological father, wealth accumulation did not statistically differ from that of women who never formed residential partnerships. These results indicate that for single mothers who are able to form lasting unions, these unions are associated with improved wealth accumulation, even after adjustment for the unequal selection of more-advantaged women into marriage.

Understanding the patterns of wealth accumulation associated with nonmarital fertility is important for several reasons. Previous studies documented single mothers’ disadvantages primarily as they related to marriage markets and “marriageable” spouses, receipt of public assistance, educational attainment, and labor force attachment and wages (e.g., Bzostek et al. 2012; Harknett and McLanahan 2004; Lichter et al. 2003; McLanahan and Percheski 2008). We advance these studies by focusing on change in wealth over time and revealing that single mothers are, on average, able to save versus accrue debt as they age, regardless of whether they marry (and whom they marry) and whether the marriages last. Indeed, our central finding is that even mothers who neither cohabited nor married over the course of our study showed modest gains in wealth with age. This finding complicates what is often an oversimplified picture of single mothers as more impoverished and less educated than women with a marital first birth. Although women with nonmarital first births have, on average, higher rates of poverty and are less educated than married peers, we emphasize what previous studies have overlooked: even women who do not later partner gain assets over time. Further, our study shows that single mothers are a diverse group of women, many of whom (at least in our cohort of Baby Boomers) later marry a biological father or stepfather. Thus, although single mothers who never marry remain significantly economically disadvantaged relative to peers with stable marriages, these women enjoy some financial security and are, in fact, statistically indistinguishable from their peers who cohabited, particularly those who cohabited with a stepfather but never married; these findings provide additional evidence that stable partnering is important for wealth accumulation (Hao 1996; Hirschl et al. 2003; Painter and Vespa 2012; Ulker 2009; Vespa and Painter 2011; Wilmoth and Koso 2002).

We found that women who married following a nonmarital birth reported greater wealth accumulation than those who remain never-married or cohabited, but paternity, union stability, and unequal selection into marriage were important limiting factors. Partnering with a biological father, particularly in an enduring marriage, was associated with the greatest gains in wealth in our growth curve models. This finding is consistent with previous research finding that paternity and union type offer distinct resources for mothers (see Hofferth 2006; Hofferth and Anderson 2003). Yet, it adds to previous research by demonstrating that early-life and ascribed characteristics—notably, race and age at first birth—restricted single mothers’ access to marriage and further wealth accumulation (shown in Table 4). It is important, then, to keep in mind that even if stable marriages to a biological father are associated with the greatest wealth accumulation, not all women have equal access to the wealth benefits of stable marriages.

Consistent with prior research on women’s mental and physical well-being following nonmarital births (Williams et al. 2011), our selection results (see Table 4) found that single mothers benefited most from intact marriages to a biological father or stepfather. Indeed, women who married but later divorced—whether the marriage was to a biological father or not—reported wealth that was statistically comparable to that of women who never partnered. Marrying did not guarantee that women in our sample would be on better financial footing than women who never partnered, adding to a larger body of literature that challenges the assertion that marriage will improve women’s well-being following a nonmarital birth (see also Lichter et al. 2003; Williams et al. 2011).

Lasting marriages between a single mother and the biological father of her child are increasingly rare, particularly among the disadvantaged. Although 24 % of the women with nonmarital births in our sample entered an enduring marriage to the biological father (see Table 1), only 16 % of low-income unwed mothers in the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study were married to the child’s biological father five years after the child’s birth (McLanahan 2009). Even more importantly, women who later form stable marriages with biological fathers are likely a select group. For example, as shown in Table 2, they are substantially advantaged in terms of their baseline levels of wealth.Footnote 12 As a result, our findings should not be viewed as evidence that promoting stable marriages among low-income single mothers will produce lasting improvements in their economic well-being. The wealth trajectories we observe among the relatively advantaged women who enter such marriages may be more positive than what would be observed among disadvantaged single mothers who are most often the focus of public attention and family policy.

It is important to emphasize that the extent to which our results can be generalized to more-recent cohorts of single mothers is unclear. The 1996 welfare reform legislation, for example, sharply curtailed the safety net available to single mothers while resulting in higher rates of employment owing to mandatory time limits for receiving cash assistance. However, because recent evidence suggests that never-married mothers have received only modest income returns to higher rates of employment (McKeever and Wolfinger 2011), this may portend more-negative consequences for their wealth attainment in future years. On the other hand, although nonmarital childbearing has become increasingly more normative in the past three decades, it has also become much less concentrated among teen mothers (Martin et al. 2012). Given lower high school graduation rates and postsecondary educational achievements of teen mothers compared with their older counterparts (Hoffman 2008), we might expect wealth trajectories of more-recent cohorts of single mothers—who are, on average, report a later age at first birth—to be more positive than those we observe.

Alongside the contributions of this study, we note three limitations. First, we were unable to compare mothers’ wealth prior to 1985, the first year for which wealth data were collected. For women who had already given birth by 1985, baseline levels of wealth were measured several years following the transition to first birth; thus, the wealth trajectories experienced by mothers may not be similarly experienced by the children in the household. Because children in this sample were born between 1977 and the mid-1990s, we may be over- or underestimating the economic impact of union formation and wealth accumulation on children’s lives for some in the sample. However, these estimates remain reliable for understanding economic disparities across mothers in the sample as they form and, in some cases, dissolve unions between the first birth and age 40. Second, single mothers who cohabit or marry likely differ from women who never partner. Although we included an extensive set of controls associated with women’s likelihood of forming partnerships (e.g., educational attainment, financial resources, and parental background), there may be unobserved differences among single mothers that are associated with both their partnering and wealth attainment and that influence the results we present here. In particular, we lack data on the characteristics of respondents’ partners because the NLSY provides data only on marital partners. Third, we did not take into account the number of cohabiting unions that a small number of women may experience. Although serial cohabitation in this cohort of women is relatively uncommon (Lichter and Qian 2008; Qian et al. 2005), single mothers are more likely to experience serial cohabitation than mothers whose first birth occurs within marriage. Thus, our models may not account for the economic instability experienced by mothers who repeatedly enter and exit cohabiting unions and for the role this may play in wealth accumulation.

Despite these limitations, our study remains the first to use wealth to consider how mothers fare economically following a nonmarital first birth, an increasingly common event in the lives of women. Although less common in the 1970s and 1980s, when our data were collected, fully 40 % of all births in 2010 were to nonmarried mothers, making it important to understand the long-term relationships between single parenthood and economic well-being for an older cohort of women who have had the opportunity to form unions, enter and exit from work, and complete childbearing as they enter into their 40s and 50s. Future studies should expand our focus on women with a nonmarital first birth to understand the wealth trajectories of married or divorced mothers who later form stable or unstable unions that may have different consequences for the financial status of their families.

Notes

In supplementary analyses, we used t tests to compare differences in means for the 121 women who were missing data on union status at or near age 40 with our sample using the means of time-invariant variables measured in 1985 (our baseline year) as well as net worth in 1985. We found only two differences: single mothers in our sample had a statistically significant lower mean for attaining a bachelor’s degree or higher; however, they had a higher mean for parental income. Importantly, we found no statistical difference in net worth between our sample and those omitted because of missing data on union status.

We adjust for inflation to 2004 dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

Five data sets were imputed for each model using SAS Proc MI and SAS Proc Mixed. Final results were obtained using SAS Proc MIAnalyze. In supplemental analysis, we compared results generated both with and without multiple imputation and found similar results.

The coefficients for these two groups were statistically equivalent.

Wealth accumulation per year of age was statistically equivalent between these two groups.

The rate of wealth accumulation for a first or second marriage was statistically indistinguishable.

Baseline wealth disadvantages of women who married the biological father versus a stepfather were statistically equivalent.

Baseline wealth was statistically equivalent for these two groups.

Equality-of-coefficients tests show that these slopes were all equivalent.

For ease of presentation, we exclude the category for women who cohabited with and never married a stepfather because the baseline and over-time wealth coefficients were statistically equivalent to the reference group.

Their greater baseline wealth is likely a result of their broader advantages in a range of sociodemographic background factors, including education and income (see Table 5). When these and other control variables are entered in the multivariate models in Table 3, this baseline wealth difference reverses direction.

References

Addo, F., & Lichter, D. T. (2013). Marriage, marital history, and black-white wealth differentials among older women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 342–362.

Amato, P. R. (2005). The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional well-being of the next generation. Future of Children, 15(2), 75–96.

Bennett, N. G., Bloom, D. E., & Miller, C. K. (1995). The influence of nonmarital childbearing on the formation of first marriages. Demography, 32, 47–62.

Berger, L. M., Carlson, M. J., Bzostek, S. H., & Osborne, C. (2008). Parenting practices of resident fathers: The role of marital and biological ties. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 625–639.

Bramlett, M. D., & Mosher, W. D. (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. (Vital and Health Statistics 23(22)) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Brown, S. L. (2004). Family structure and child well-being: The significance of parental cohabitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 351–367.

Brown, S. L. (2010). Marriage and child well‐being: Research and policy perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 1059–1077.

Bzostek, S. H., McLanahan, S. S., & Carlson, M. J. (2012). Mothers’ repartnering after a nonmarital birth. Social Forces, 90, 817–841.

Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861.

Cherlin, A. J. (2010). Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 403–419.

Clogg, C., Petkova, E., & Haritou, A. (1995). Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. American Journal of Sociology, 100, 1261–1293.

Cohen, P. N. (2002). Cohabitation and the declining marriage premium for men. Work and Occupations, 29, 346–363.

Conley, D. (1999). Being black, living in the red. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Deb, P., & Trivedi, P. K. (2006). Maximum simulated likelihood estimation of a negative binomial regression model with multinomial endogenous treatment. Stata Journal, 6, 246–255.

Frech, A., & Damaske, S. (2012). The relationships between mothers’ work pathways and physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 396–412.

Graefe, D., & Lichter, D. (1999). Life course transitions of American children: Parental cohabitation, marriage, and single motherhood. Demography, 36, 205–217.

Hao, L. (1996). Family structure, private transfers, and the economic well-being of families with children. Social Forces, 75, 269–292.

Harknett, K., & McLanahan, S. (2004). Explaining racial and ethnic differences in marriage among new, unwed parents. American Sociological Review, 69, 790–811.

Heimdal, K. R., & Houseknecht, S. K. (2003). Cohabiting and married couples’ income organization: Approaches in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 525–538.

Hirschl, T. A., Altobelli, J., & Rank, M. R. (2003). Does marriage increase the odds of affluence? Exploring the life course probabilities. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 927–938.

Hofferth, S. L. (2006). Residential father family type and child well-being: Investment versus selection. Demography, 43, 53–77.

Hofferth, S. L., & Anderson, K. G. (2003). Are all dads equal? Biology versus marriage as a basis for paternal investment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 213–232.

Hoffman, S. D. (2008). Updated estimates of the consequences of teen childbearing for mothers. In S. D. Hoffman & R. D. Maynard (Eds.), Kids having kids: Economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy (2nd ed., pp. 74–118). Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Hohmann-Marriott, B. (2011). Coparenting and father involvement in married and unmarried coresident couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 296–309.

Johnson, R. W., & Favreault, M. M. (2004). Economic status in later life among women who raised children outside of marriage. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59, S315–S323.

Keister, L. A. (2000). Race and wealth inequality: The impact of racial differences in asset ownership on the distribution of household wealth. Social Science Research, 29, 477–502.

Keister, L. A. (2004). Race, family structure, and wealth: The effect of childhood family on adult asset ownership. Sociological Perspectives, 47, 161–187.

Killewald, A. (2013). A reconsideration of the fatherhood premium marriage, coresidence, biology, and fathers’ wages. American Sociological Review, 78, 96–116.

Lichter, D. T., Graefe, D. R., & Brown, J. B. (2003). Is marriage a panacea? Union formation among economically disadvantaged unwed mothers. Social Problems, 50, 60–86.

Lichter, D. T., & Qian, Z. (2008). Serial cohabitation and the marital life course. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 861–878.

Manning, W. D., & Brown, S. (2006). Children’s economic well-being in married and cohabiting parent families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 345–362.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Ventura, S. J., Osterman, M. J. K., Wilson, E. C., & Mathews, T. J. (2012). Births: Final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 61, 1–72.

McKeever, M., & Wolfinger, N. (2011). Thanks for nothing: Income and labor force participation for never-married mothers since 1982. Social Science Research, 40, 63–76.

McLanahan, S. (2009). Fragile families and the reproduction of poverty. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621, 111–131.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

McLanahan, S., & Sandefur, G. (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Oliver, M. L., & Shapiro, T. M. (2006). Black wealth, white wealth: A new perspective on racial inequality. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Osborne, C., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2007). Married and cohabiting parents’ relationship stability: A focus on race and ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1345–1366.

Ozawa, M. N., & Yoon, H.-S. (2002). The economic benefit of remarriage. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 36(3–4), 21–39.

Painter, M. A., & Shafer, K. (2011). Race/ethnicity, children, and household wealth accumulation. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41, 661–691.

Painter, M., & Vespa, J. (2012). The role of cohabitation in asset and debt accumulation during marriage. Journal of Family and Economic Issues: 1–16.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36, 859–866.

Pezzin, L. E., & Schone, B. S. (1999). Parental marital disruption and intergenerational transfers: An analysis of lone elderly parents and their children. Demography, 36, 287–297.

Pollak, R. A. (1985). A transaction cost approach to families and households. Journal of Economic Literature, 23, 581–608.

Qian, Z., Lichter, D. T., & Mellott, L. M. (2005). Out-of-wedlock childbearing, marital prospects and mate selection. Social Forces, 84, 473–491.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Sassler, S. (2004). The process of entering into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 491–505.

Sassler, S., & Miller, A. J. (2011). Class differences in cohabitation processes. Family Relations, 60, 163–177.

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42, 621–646.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Smock, P. J. (2000). Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 1–20.

Smock, P. J., & Greenland, F. R. (2010). Diversity in pathways to parenthood: Patterns, implications, and emerging research directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 576–593.

Smock, P. J., Manning, W. D., & Gupta, S. (1999). The effect of marriage and divorce on women’s economic well-being. American Sociological Review, 64, 794–812.

Ulker, A. (2009). Wealth holdings and portfolio allocation of the elderly: The role of marital history. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30, 90–108.

Upchurch, D., Lillard, L., & Panis, C. (2002). Nonmarital childbearing: Influences of education, marriage, and fertility. Demography, 39, 311–329.

Vespa, J., & Painter, M. (2011). Cohabitation history, marriage, and wealth accumulation. Demography, 48, 983–1004.

Von Hippel, P. T. (2007). Regression with missing Y’s: An improved strategy for analyzing multiply imputed data.” Sociological Methodology, 37, 83–117.

Waite, L. J. (1995). Does marriage matter? Demography, 32, 483–507.

Williams, K., Sassler, S., Frech, A., Addo, F., & Cooksey, E. (2011). Nonmarital childbearing, union history, and women’s health at midlife. American Sociological Review, 76, 465–486.

Williams, K., Sassler, S., & Nicholson, L. (2008). For better or for worse? The consequences of marriage and cohabitation for single mothers. Social Forces, 86, 1481–1511.

Wilmoth, J., & Koso, G. (2002). Does marital history matter? Marital status and wealth outcomes among preretirement adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 254–268.

Acknowledgments

The first two authors contributed equally. The authors would like to thank Jonathan Vespa for comments on a previous draft. This research was supported in part by Grant Number R01HD054866 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (PI: Kristi Williams). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Table 5

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Painter, M., Frech, A. & Williams, K. Nonmarital Fertility, Union History, and Women’s Wealth. Demography 52, 153–182 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0367-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0367-9