Abstract

A well-qualified, well-paid, stable workforce with high psychological and emotional wellbeing is critical to the provision of quality early childhood education and care, yet workforce shortages and high turnover persist in Australia and internationally. This paper uses ecological theory to conceptualise and make sense of findings from research that has investigated the recruitment, retention and wellbeing of early childhood teachers in Australia. The theoretical framing of early childhood teacher workforce issues proffered in the paper highlights the utility of considering these issues from a holistic ecological perspective. Analysis of Australian early childhood workforce studies draws attention to the need for large-scale, longitudinal research that holistically investigates influences on the attracting, retaining and sustaining of early childhood teachers, and the impact of these influences on teacher quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attracting, retaining and sustaining the early childhood education and care (ECECFootnote 1) workforce have long been issues of national and international significance (OECD 2006, 2019; Productivity Commission 2011; Whitebook et al. 2014; Totenhagen et al. 2016; Pascoe & Brennan 2017; Jackson 2020;). While it is consistently recognised that a well-qualified, well-paid, stable workforce with high psychological and emotional wellbeing is critical to the provision of quality ECEC (OECD 2006; Whitebook et al. 2014; Cumming 2017; Thorpe et al. 2020), workforce shortages and high turnover persist (OECD 2012). Of particular concern is the high turnover and shortage of degree-qualified early childhood teachers (ECTs)Footnote 2, given the established significant contribution they make to high-quality ECEC (Sylva et al. 2004; Tayler 2016; Manning et al. 2019).

In Australia, the ECEC workforce is composed of a mix of degree-qualified ECTs and diploma and certificate-trained educators, and there are workforce shortages across all three groups (Department of Education, Skills & Employment 2019). Attracting early childhood preservice teachers and retaining them following graduation is of particular concern, with the supply of ECTs falling short of current and projected need (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2014; Shah 2015; Future Tracks 2019). Recent figures show that the completion rate for undergraduate initial teacher education programs in Australia, including birth-eight and birth-12 years’ early childhood programs, is only 51% (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL] 2019). Policy analysts have warned that this low completion rate, coupled with government projections that by 2023 a further 29,000 ECTs will be needed to meet regulatory requirements (Department of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business n.d.), will mean a sector shortfall of nearly 18,000 ECTs in 2023, leaving at least one-third of preschoolsFootnote 3 without the ECTs they need (O'Connell 2019). Moreover, the high staff turnover of ECTs and educators more broadly has been deemed to range from 20 to 21% (Irvine et al. 2016; Jones et al. 2017) to 33–37% (metropolitan and remote services, respectively) (Thorpe et al. 2020). A recent ECEC workforce census noted that the average tenure for qualified educatorsFootnote 4 at their current service was only 3.6 years (Social Research Centre 2017), while less than a third of educators (27.8%) have 10 or more years’ sector experience (Social Research Centre 2014).

To address these supply and retention workforce issues in Australia, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) has endorsed national workforce strategies (Standing Council on School Education and Early Childhood [SCSEEC] 2012; Education Council 2019). Four state governments have also implemented ECEC workforce strategies that include initiatives such as campaigns to promote the value of ECEC and attract more students to ECT programs; scholarships for pre-service ECTs; scholarships and pathways to support educators’ upskilling from a diploma to an ECT qualification; employment incentives for graduate ECTs; and opportunities for professional development (Early Childhood Australia [Tasmania] and the Tasmanian Department of Education 2017; NSW Department of Education 2018; Victorian Department of Education and Training 2019; Queensland Department of Education and Training 2020). Collectively, these strategies recognise that without improvements in the supply and retention of ECTs, policy initiatives (Council of Australian Governments [COAG] 2009) and regulatory reforms (Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority [ACECQA], n.d.; Commonwealth of Australia 2010) aimed at improving the quality of the ECEC sector through increased supply of ECTs, are at risk.

Given the significance and complexity of entrenched ECT workforce issues, policy analysts have cautioned that government responses must be coherent, substantive and evidence-based (Press et al. 2015; Pascoe and Brenman 2017; Jackson 2020). In the section that follows we draw on a holistic, ecological systems framework to conceptualise findings from Australian research that has investigated ECT workforce issues. We show that while extant research highlights barriers to attracting, retaining and sustaining ECTs in Australia, a comprehensive research base to inform government policy specific to ECTs is still lacking. Relative to the critical role teachers play in the provision of high-quality ECEC, limited research has focussed on ECT workforce issues. In particular, three shortcomings that we highlight in the present analysis are first, the lack of published studies that have longitudinally tracked the career trajectories of ECTs; second, the typically narrow rather than holistic lens through which recruitment, retention, and wellbeing issues have been investigated; and third, the small rather than large-scale scope of most extant ECEC workforce research.

ECT workforce issues through an ecological lens

As we demonstrate below, research from the Australian context points to multiple factors that impact on the recruitment, retention and wellbeing of ECTs. Extending on studies that have utilised ecological theory to holistically conceptualise workforce issues in ECEC (McKinlay et al. 2018) and school contexts (Zavelevsky and Lishchinsky 2020), and the retention of undergraduate students more broadly (Loh et al. 2020), we draw on Bronfenbrenner’s (1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris 1998; Rosa and Tudge 2013) bioecological model to show that entrenched ECT workforce issues in Australia are attributable to interconnected and bi-directional systemic factors that are proximal and distal to ECTs. Such a systems approach is consistent with calls to examine workforce issues through a holistic frame that gives consideration to the interplay of individual, relational, organisational, sociocultural and political influences (Sumsion 2002; Cumming 2017; Cumming and Wong 2019; Jones et al. 2019).

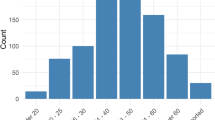

Applying Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model to the ECT workforce ecosystem results in five interconnected subsystems, represented as nested spheres that impact on each other. Accordingly, each subsystem can individually but also collectively impact on the recruitment, retention and wellbeing of ECTs. At the centre of the ecosystem are the individual characteristics and attributes of ECT preservice and graduate teachers, such as age, gender, cultural background, experience in the ECEC context, and levels of job satisfaction, teaching self-efficacy and wellbeing. Impacting on ECTs are four extrinsic teaching contexts. First is the microsystem; comprising higher education institutions where preservice ECTs complete their teaching qualification, and ECEC services that employ ECTs. Second is the mesosystem; the interactions and degree of harmony or dissonance between components of the microsystem, such as relationships with colleagues, families and the service’s governing body. Third is the exosystem; broader sector policies and structural conditions such as regulations, wages, and tertiary institutions’ requirements and provisioning of early childhood initial teacher education programs. Fourth is the macrosystem; societal culture, values and dominant discourses pertaining to care, early learning and the value of ECEC. Operating across these four levels is the chronosystem, reflecting the influence of history and time, such as the development of the ECEC sector in Australia. Figure 1 illustrates this conceptualisation. Situating workforce issues within this ecological systems frame provides a holistic lens through which individual, workplace, relational, socio-political and discursive influences on ECT workforce issues can be coherently examined within and across the different levels.

Factors presented below that contribute to, or conversely, mitigate ECT workforce issues were drawn from empirical research, literature reviews, ECEC workforce censuses and government reports that have included or specifically focussed on ECTs in Australia. To extract peer-reviewed research for analysis, A+ Education, EbscoHost, Proquest Education and PsycInfo databases were utilised, with searches confined to peer-reviewed journal articles from 2000 onwards. The following search terms were used: “early childhood teach*” AND “Australia” AND “workforce”/“turnover”/“retention”/“job satisfaction”/“burnout”/ OR “wellbeing”. Additional relevant research papers were located from the reference lists of the articles retrieved. Relevant workforce censuses and reports were also sourced from the authors’ own professional libraries. In sum, 38 empirical peer-reviewed published studies were analysed (See Appendix 1 for a summary of the aims and methodologies of these papers), and 18 further papers (literature reviews and reports) reviewed.

Individual factors

A range of demographic and individual variables influence preservice and graduate ECT recruitment, retention and wellbeing. A large Australian study of beginning early childhood, primary and secondary preservice teachers showed that intrinsic motivations for becoming an ECT include a passion for teaching and working with young children (Richardson et al. 2011). In the ECEC context, however, these motivations in themselves do not ensure retention (Thorpe et al. 2020). Moral and altruistic motivations—making a difference and supporting children’s rights—draw students and teachers to ECEC (Sumsion 2004; Fenech et al. 2009; Richardson et al. 2011; Thorpe et al. 2011; Ciuciu and Robertson 2019). One study of preservice teacher enrolments in an EC initial teacher education program over a 14-year period showed that male students were significantly more likely than female students to withdraw prior to completion (65.6% vs 47.5% of respective total male and female enrolments) (Kirk 2020). In this study, the male cohort tended not to intrinsically view early childhood teaching as a career choice, and attitudinal barriers together with having few male peers contributed to their withdrawal from the program.

A small-scale qualitative study of seven thriving ECTs found other personal attributes that support ECT retention, namely self-reflexivity; a drive to overcome challenges; a preparedness to invest unpaid hours while maintaining work-life balance; determination and persistence; a commitment to ongoing professional development; and a capacity and willingness to formally or informally exercise leadership (Sumsion 2004). An exploration of professional identities associated with retention of 14 educators and four ECTs from two long day care services included a longstanding desire to become an educator; having significant others who are teachers; deriving esteem and a positive self-image from working with children; and enacting the educator role from a sense of mastery (Cranitch 2017). For some preservice ECTs, a perception that this work will be compatible with family responsibilities provides a personal motivator to enrol in an early childhood ITE program (Richardson et al. 2011; Ciuciu and Robertson 2019).

The values, beliefs and aspirations of preservice teachers, in particular, the perception that working in an ECEC setting is not ‘real teaching’ and an associated aspiration to teach rather than seemingly only care for children, steer those enrolled in a dual (EC and primary) qualification to employment in the school rather than EC sector, to teach primary school-aged children (Liu and Boyd 2018). For those ECTs who do work in ECEC, younger and more qualified educators are more likely to leave their workplace and potentially also the sector if: they are studying to attain a higher ECEC or different qualification (Watson 2006; Irvine et al. 2016; Thorpe et al. 2020); their familial circumstances mean that they cannot afford to live on low wages (Irvine et al. 2016; McKinlay et al. 2018); they experience a disconnect between their motivation/love of children and the lived demands of the ECT role (Irvine et al. 2016); or they are women and leave due to pregnancy and/or to support the career trajectory of their spouse (Productivity Commission 2011; Thorpe et al. 2020). A tendency to put the needs of children, families and other educators before their own, and to underreport workplace issues and injuries, can mean that wellbeing issues in ECEC are not shared or addressed, and may become exacerbated over time (Logan et al. 2020). A diminishing passion for teaching, and the development of burnout, also contribute to ECTs’ attrition (McKinlay et al. 2018), while progression from teaching into managerial roles can support retention (Thorpe et al. 2020).

Microsystem factors

ECTs have direct interaction with three microsystems at different points of their career. First are the early childhood teacher education contexts within which preservice ECTs complete their teaching qualification; second, the ECEC services in which preservice teachers complete professional experience; and third, the ECEC services where ECTs are employed.

Many early childhood teacher education program/programs in Australia are dual early childhood/primary qualifications that span birth-eight or birth-12 years, with variable ECEC-specific content and professional experience (Boyd et al. 2020). Many graduates of these programs choose or aspire to work with primary school-aged children in schools rather than with younger children in ECEC, and in preschools rather than long day care (Farrell et al. 2000; Sumsion 2002; Thorpe et al. 2011; Nolan and Rouse 2013; Harrison and Heinrich-Joerdens 2017; Liu and Boyd 2018; Boyd and Newman 2019; Gibson et al. 2019; Mahony et al. 2020). These consistent findings contrast attempts within early childhood teacher education programs to promote ECEC as early education and not just about care (Gibson et al. 2018). The breadth of these programs has generated concern about how well-prepared graduates are to teach in the early years sector (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2014; Boyd and Newman 2019; Boyd et al. 2020). Similar concern has been raised about how well-prepared graduates of postgraduate EC teaching programs are to meet the demands of the job (Ciuciu and Robertson 2019). “Pedagogical challenges” have also been identified in the delivery of two-year master’s early childhood teacher education programs whose cohorts include mature-age international students unfamiliar with the Australian ECEC context (Fenech et al. 2009, p. 208). Conversely, ECEC employers have expressed a preference for birth-five teacher graduates, who they consider best qualified to teach in the early years sector (Boyd et al. 2020).

The quality of education and care in services within which preservice ECTs undertake professional experience can influence their career choices (Thorpe et al. 2012; Nolan and Rouse 2013). Placement in low-quality services can deter preservice teachers from seeking a teaching position in the ECEC sector (Thorpe et al. 2011; Boyd and Newman 2019). Conversely, placements undertaken in settings characterised by strong leadership can steer students completing a dual early childhood/primary teacher education program to ECEC settings (Thorpe et al. 2012).

Following completion of an early childhood teacher education qualification, the ECEC service as a workplace represents a key systemic influence on workforce issues, through ECTs’ levels of job satisfaction and associated turnover intent (Jones et al. 2017). On the one hand, ECEC services can be sites where ECTs experience high levels of stress and emotional exhaustion (Jovanovic 2013; Irvine et al. 2016), particularly in long day care (Social Research Centre 2014). Intense work environments where ECTs undertake multiple, complex and demanding tasks across the course of a day and at the same time (Harrison et al. 2019), where there is limited time to complete roles and responsibilities (Jovanovic 2013; Cumming 2017; McKinlay et al. 2018), no space for staff to experience physical and mental rest during their breaks (Logan et al. 2020), limited opportunity to work collegially (Sumsion 2002; Jovanovic 2013) or scope to exercise professional autonomy (Cumming 2015) can exacerbate stress and job frustration. In ECEC workplace environments, ECTs can also be regularly exposed to noise levels that exceed national occupational health and safety standards which can lead to psychological stress (Grebennikov and Wiggins 2006). ECTs’ occupational health and safety can be further compromised by hazards in the workplace, the physical and emotional intensity involved in teaching young children, and children’s challenging behaviours (Logan et al. 2020). These issues make ECEC settings one of the most hazardous workplaces in Australia, as reflected in the high number of workers’ compensation claims made in 2016–2017, particularly for physical injuries (Cumming et al. 2020).

Employers who recognise and invest in ECTs “as professionals” (Sumsion 2004, p. 283) do much to support the recruitment, retention and wellbeing of ECTs. This recognition and investment in ECTs can be through the provisioning of material and non-material benefits and affordances. Above award pay and working conditions (e.g. paid study leave; programing time) are material benefits consistently cited in the early childhood workforce literature reviewed (Bretherton 2010a, b; McKinlay et al. 2018; PricewaterhouseCoopers 2014). Services that provide support and financial incentives for diploma-qualified educators to become ECT-qualified (e.g. paid study leave; guaranteed ECT position at course completion) enable educators wanting to upskill to do so (Future Tracks 2019; Boyd et al. 2020).

Non-material benefits or affordances in the ECEC workplace can enhance job satisfaction and in turn, support ECT retention and wellbeing. Such benefits identified in the literature include above minimum standard ratio and staff qualification requirements (Bretherton 2010b; Jones et al. 2017); effective service leadership and management (Jones et al. 2017; Thorpe et al. 2020); scope to exercise professional autonomy and judgement (Sumsion 2004; Cumming 2017; Jones et al. 2017; Jones et al. 2019; Thorpe et al. 2020); the provision of mentoring and professional development opportunities through within-service learning communities and access to conferences and professional courses (Sumsion 2004); flexible work arrangements (McKinlay et al. 2018); and a culture that is family-friendly (Bretherton 2010a; PricewaterhouseCoopers 2014; McKinlay et al. 2018; Jones et al. 2019). A workplace with strong morale, that enables ECTs to have a strong teacher identity, and where job satisfaction and other non-financial rewards are enjoyed (e.g. seeing children develop; opportunities for career progression, creativity, autonomy and leadership) fosters retention in the ECEC sector (Sumsion 2004; Thorpe et al. 2011; McKinlay et al. 2018).

Mesosystem factors

Synergies between microsystem components, most notably between ECTs and colleagues, the centre director, and families, can support workforce retention and wellbeing. The absence of other teachers in long day care settings (Thorpe et al. 2011; Ciuciu and Robertson 2019) and a lack of collegial relationships and teamwork can diminish a commitment to teaching and exacerbate stress, job dissatisfaction and attrition (Sumsion 2002; Cumming 2015; McKinlay et al. 2018). Moreover, working in teaching contexts that are not professionally stimulating (e.g. lacking a culture of critical reflection), where professional development is not valued, or where a shared philosophy among staff is lacking, can be demoralising and trigger attrition (Sumsion 2002; Bretherton 2010b).

Conversely, supportive, collegial relationships where ECTs are valued, mentored, committed to a shared philosophy, and feel a sense of belonging, enhance job commitment, the development of a strong professional identity, resilience to work stressors and wellbeing (Sumsion 2004; Cranitch 2017; Cumming 2017; Jones et al. 2017; Jones et al. 2019; Ciuciu and Robertson 2019). A supportive and competent centre director who identifies and addresses wellbeing issues can mitigate ECTs’ occupational stress and injury (Logan et al. 2020). Employers’ and families’ recognition of ECTs’ professional knowledge and skills also contributes to ECTs thriving in their work (Sumsion 2004). Employers and providers who engage in political advocacy to raise the profile and status of ECTs can affirm ECTs’ own professional identity and inspire hope for improved wages and professional status across the sector (Sumsion 2004).

Exosystem factors

The broader systems’ influences discussed in this section pertain to levers that support or constrain entry into and completion of early childhood teacher education programs; the broader ECEC and education landscape in Australia; and relevant government policy that govern ECEC and the work ECTs do.

For diploma-qualified educators, complex university entry systems, perceived high university fees, inconsistent recognition of prior learning, and low ECT wages can prohibit enrolment in an ECT degree (Social Research Centre 2014; Future Tracks 2019). Moreover, upskilling to an ECT qualification can be difficult (Watson 2006) and does not always translate to an increased supply of ECTs, given that completing an ECT qualification also provides a pathway out of ‘child care’ to employment in the school sector (Nolan and Rouse 2013; Thorpe 2020; Watson 2006). For postgraduate preservice ECTs, a lack of government financial support can exacerbate financial pressures that threaten completion of early childhood teacher education programs (Fenech et al. 2009).

Low wages, low professional status, and lack of pay parity with teachers employed in schools are disincentives for preservice ECTs to work in ECEC, particularly long day care (Bretherton 2010a; Thorpe et al. 2011; Productivity Commission 2014; Irvine et al. 2016; Liu and Boyd 2018; Boyd and Newman 2019). Moreover, ECTs who do work in long day care but then leave, attribute their decision to these exosystem factors (Bretherton 2010a; PricewaterhouseCoopers 2014; Social Research Centre 2014; Irvine et al. 2016). These pay issues are exacerbated by variable industrial awards and enterprise agreements under which ECTs may be employed and which offer substantially different pay and working conditions, such as programing time and annual leave (Ciuciu and Robertson 2019). Rural and remote services experience even greater challenges attracting ECTs (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2014) and retaining educators (Thorpe et al. 2020).

Longstanding regulatory burden (and associated unpaid hours and constraints on professional autonomy) (Fenech et al. 2006; Fenech et al. 2007; Bretherton 2010b; Social Research Centre 2014; Grant et al. 2016; Irvine et al. 2016; Grant et al. 2018;), together with the experience of working long hours, are detrimental to work-life balance, job satisfaction and the retention and wellbeing of ECTs (Ciuciu and Robertson 2019). Conversely, Australia’s Early Years Learning Framework (Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations [DEEWR] 2009) does not prescribe curriculum; thus, its scope for teacher autonomy and professional judgement can enhance job satisfaction and retention (McKinlay et al. 2018).

The marketisation of ECEC in Australia, particularly of long day care, has emerged as an exosystem influence on ECT recruitment, retention and wellbeing in three ways. First, government funding and operation of schools compared to a heavily marketised long day care sector contributes to a perceived professional versus non-professional divide (Mahony et al. 2020) that can steer ECT graduates of birth-eight and birth-12 years’ programs to a school teaching career. Second, ECTs employed in large private services or private long day care chains have higher levels of turnover intent than those employed in stand-alone or large not-for-profit services (Jones et al. 2017). Third, the commercial interests of the for-profit sector (Sumsion 2007) and the historical and continued trend of for-profit services generally not meeting quality standards and advocating against improved regulations (Fenech 2019) may mean that ECTs in these workplaces experience work dissatisfaction, stress and turnover.

Macrosystem factors

ECEC has long been positioned within care and maternalism discourses (Gibson 2013) whereby working with young children is regarded as women’s work and attracts a predominantly female workforce, with low professional status and pay (Kirk 2020). The gender composition of the ECT workforce is compounded by gender stereotypes, a feminised preservice and workforce culture, and societal mistrust of men who want to work in ECEC (Sumsion 2000). It is unclear from the literature reviewed whether these discourses underpin career advisors’ understandings of early childhood teaching, or whether counter discourses such as teaching as intellectual or political work (Sumsion 2003, 2004) are promoted by advisors and tertiary teacher educators.

The prevailing discourse that education begins with formal schooling (Nuttall 2018) can also influence the professional identities of preservice teachers such that they do not consider ECEC a viable option (Gibson 2013). Moreover, entrenched perceptions of long day care as ‘care’ and preschool as ‘education’ contribute to challenges attracting and retaining ECTs in long day care (Irvine et al. 2016). Moves to professionalise the EC workforce through regulatory reform can generate performative discourses of professionalism with associated expectations and practices that impede teacher-professionalism (Cumming 2015; Grant et al. 2016), for example, professional trust and autonomy being eroded by increased emphases to provide documentary evidence to ‘prove’ service quality.

Chronosystem factors

Findings from the literature reviewed paid limited attention to historical and temporal influences on ECT workforce issues. For example, no attention had been paid to the impact of opportunities for career progression, or whether ECTs who continue working in the sector tend to be employed in particular positions, services providing a high standard of quality ECEC, or provider types. What is known, and as noted earlier, is that while students’ life histories mean that they enrol in an EC teacher education program with the intention to teach children, progression through a dual degree program can shift their aspirations from teaching in ECEC to teaching in a school (Farrell et al. 2000). Further, educators over time transition across the sector, from long day care to preschool, seeking better remuneration, status and work conditions (Irvine et al. 2016). This observed shift away from long day care to preschool is indicative of a historical and entrenched perceived differentiation in Australia of long day care being about care and supporting workforce participation, and preschool more about early education (Cheeseman and Torr 2009).

Limitations to current understandings about ECT workforce challenges

Despite a substantive body of research that has informed understandings about ECT workforce issues in Australia, policy analysts have asserted that Australia lacks the evidence base required to sufficiently inform strategic policy responses (Press et al. 2015). Accordingly, policy initiatives aimed at addressing workforce challenges may have limited impact (Cumming et al. 2015). We attribute this perceived limited evidence base to a lack of large-scale research that has systematically and longitudinally investigated how the collective individual, microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem factors play out in ECTs’ career trajectories. To date, other than Sumsion’s (2002) longitudinal phenomenological study of the “becoming, being and unbecoming” (p. 869) of one ECT, no published Australian ECEC workforce study has investigated the recruitment, retention and/or wellbeing of ECTs from preservice to mid-career and beyond. This is a noteworthy omission, given “the dynamism of relationships of people, places, materials and regulation over time [our emphasis], and the necessity of seeing efforts to support wellbeing [and thus workforce issues] as ongoing rather than a one-off [our emphasis]” (Cumming and Wong 2019, p. 276). From an ecological perspective, the lack of attention to the career trajectories of ECTs over time, and within their situated workplace contexts, negates the potential to identify chronosystem influences on ECTs’ workforce challenges, and how other systems factors interact over time to influence the career decisions of preservice and graduate ECTs.

The ecological lens utilised in this paper highlights the utility of government and service ECEC workforce policies being developed from an understanding of what is occurring at the individual and contextual levels, at different points along an ECT’s career pathway. Most studies to date, however, have focussed on specific influences within the individual, microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem or macrosystem of research participants. Collectively, extant research on Australian ECEC workforce issues falls short of a holistic consideration of how these interconnected systems collectively impact ECTs’ career progression.

The sample size of the empirical studies cited in this paper is a further limitation of Australian research that has to date investigated workforce issues in ECEC. Most studies (n = 14) are small-scale qualitative investigations of the perspectives of ten or fewer ECTs (e.g. Cranitch 2017; Cumming 2015; Jones et al. 2019; Sumsion 2000, 2002, 2004). While quantitative studies reviewed for this paper had larger sample sizes, most focussed on preservice ECTs (e.g. Nolan and Rouse 2013; Harrison and Heinrich-Joerdens 2017; Boyd and Newman 2019). There is a need for both large-scale quantitative and small-scale qualitative studies to shed light on the complex nature of ECT’s work (Press et al. 2015). The qualitative studies reported in this paper provide rich descriptions and nuanced understandings about the lived experience of being an ECT, and enable theory building. However, it is only through large-scale and longitudinal studies, such as the continuing ‘FIT-Choice’ (Factors Influencing Teaching Choice; www.fitchoice.org) project of Watt and Richardson which tracks the trajectories of 2007 future teachers from their entry to teacher education until their mid-career teaching (see for retention rates, Lazarides et al. 2020), that we are able to discern how widespread these experiences are, and test the robustness of theories developed.

Notwithstanding the value of the four large-scale studies reviewed in this paper (Richardson and Watt 2006; Irvine et al. 2016; Jones et al. 2017; Thorpe et al. 2020), surprisingly little attention has been focussed on workforce issues specific to ECTs. Irvine et al. and Thorpe et al. in addition to eight smaller-scale studies (Grebennikopv and Wiggins 2006; Brethherton 2010a; Jovanovic, 2013; Cranitch 2017; Harrison et al. 2019; Jones et al. 2019; Cumming et al. 2020; Logan, Cumming and Wong 2020) and reports (e.g. Social Research Centre 2017) conflate findings from ECT and educator (certificate or diploma trained) participants, making it difficult to discern issues that may be specific to ECTs. Further, Richardson and Watt’s (2006) investigation of preservice teachers’ motivations for enrolling in a teacher education degree included early childhood as well as primary and secondary students, yet published findings do not provide disaggregated data for the early childhood cohort.

Exacerbating this silencing of ECTs’ perspectives are issues pertaining to the collection of ECEC workforce data. First, data on workforce issues tend to be extracted from studies and reports that focus more on long day care than preschool, or include ECEC settings such as occasional care and family day care, where ECTs are generally not employed. Second, Australia’s ECEC national workforce census no longer collects data from ECTs employed in preschools (Social Research Centre 2017). Third, the Australian Graduate Survey (now referred to as the Graduate Outcomes Survey) is distributed to graduates approximately four months after graduation, but ECEC teaching contexts are not included in the job categories listed, nor does the ‘point in time’ data capture ECTs’ future career trajectories (Gibson et al. 2019). This collective downplaying and exclusion of ECTs has potential to render the ECT workforce an invisible cohort of teachers in the Australian education landscape, endangering efforts to effectively recruit, retain and sustain them in the ECEC sector.

Conclusion

Responding to the ongoing and intensifying scrutiny of teacher education in Australia and internationally, education policy scholars have maintained that a shift in research focus and methodology is needed to provide “the greatest power to respond” (Rowan et al. 2015, p. 275). With barriers to recruiting, retaining and sustaining ECTs persisting despite the two decades of research and published reports cited in this paper, this call is pertinent to the investigation of ECEC workforce issues in Australia.

While much valuable research has investigated ECEC workforce issues to date, the often small-scale, piecemeal and cross-sectional designs, conflation of ECT and other educator findings, and greater focus on long day care rather than preschool contexts, leaves much scope to extend understandings about the ECT workforce in Australia. Our ecological framing highlights the multiple and persistent barriers evident within each level of the ECT workforce ecosystem, while also pointing to the complex and dynamic interplay across levels. Future large-scale research that adopts such a holistic approach to longitudinally investigate the situated career trajectories of preservice and graduate ECTs has much potential to progress nuanced understandings about these complexities and interrelationships.

Returning to the premise on which this paper began—that the attracting, retaining and wellbeing of high-calibre ECTs is critical to the provision of quality ECEC—each level of the workforce ecosystem, together with the synergy of influences within and across levels, can impact the effectiveness of ECTs, and thus the quality of ECEC they provide. Notably, while there is an established relationship between university-qualified teachers and high-quality ECEC, research has yet to explicitly investigate the influence of ecological systems factors pertaining to workforce issues on teacher quality. For example, how do the multiplicity of complex and dynamic factors that impact on ECT recruitment, retention and wellbeing impact the efficacy of ECTs who are working in the sector? Incorporating this focus into the line of enquiry we propose has scope to strengthen the evidence base to inform ECEC workforce policy in ways that would support regulatory approaches to quality and quality improvement.

Change history

12 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00441-z

Notes

While ECEC is internationally recognised as birth-eight years of age, in this paper our focus is on the early years, that is, birth-five years.

ECTs in this paper refer to graduate teachers with undergraduate or postgraduate degrees that qualify them to work with children in the birth-five years age group. As will be explained later in the paper, early childhood degrees in Australia can be birth-five, birth-eight, or birth-12 years focussed.

In Australia ECTs are generally employed in preschools or long day care centres. Preschools cater for children 3-5 years and typically operate 9am-3pm during school terms. In contrast, long day care services operate for at least 48 weeks of the year, for a minimum 8 hours per day, thus catering for working families. Both services have an education focus, with ECTs required to implement an Early Years Learning Framework (Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) 2009) and meet national quality standards (Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA), 2020).

References

Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2020). Guide to the National Quality Framework. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-01/Guide-to-the-NQF_0.pdf.

Australian Children's Education and Care Quality Authority [ACECQA]. (n.d.). Additional staffing requirement from 1 January 2020. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/qualification-requirements/additional-staffing-requirement-1-january-2020.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL]. (2019). ITE Data Report 2019. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/tools-resources/resource/ite-data-report-2019.

Boyd, W. (2020). Australian early childhood teacher programs: Perspectives and comparisons to Finland, Norway and Sweden. Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Boyd, W., & Newman, L. (2019). Primary + Early Childhood = chalk and cheese? Tensions in undertaking an early childhood/primary education degree. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 44(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119841456.

Boyd, W., Wong, S., Fenech, M., Mahony, L., Warren, J., Lee, I.-F., & Cheeseman, S. (2020). Employers’ perspectives of how well prepared early childhood teacher graduates are to work in early childhood education and care services. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120935997.

Bretherton, T. (2010a). Developing the child care workforce: Understanding ‘fight’ or ‘flight’ amongst workers. https://www.ncver.edu.au/__data/assets/file/0019/2872/2261.pdf.

Bretherton, T. (2010b). Workforce development in early childhood education and care: A research overview. Retrieved from: https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/workforce-development-in-early-childhood-education-and-care-research-overview.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.). Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 993–1023). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Cheeseman, S., & Torr, J. (2009). From Ideology to productivity: Reforming early childhood education and care in Australia. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 3(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/2288-6729-3-1-61.

Ciuciu, J., & Robertson, N. (2019). “That’s what you want to do as a teacher, make a difference, let the child be, have high expectations”: Stories of becoming, being and unbecoming an early childhood teacher. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(11), 79–95.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2010). The Education and Care Services National Law Act 2010, . http://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/Domino/Web_Notes/LDMS/LTObject_Store/LTObjSt5.nsf/DDE300B846EED9C7CA257616000A3571/A36B365963580A90CA25780E0011D8D4/$FILE/10-69aa001%20authorised.pdf. Accessed 17 Feb 2011.

Council of Australian Governments [COAG]. (2009). National Partnership Agreement on the Quality Agenda for Early Childhood Education and Care. http://files.acecqa.gov.au/files/NQF/nap_national_quality_agenda_early_childhood_education_care_signature.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2017.

Cranitch, C. S. (2017). Professional identity: Shaping attraction, retention, and training intentions in early childhood education and care. Master of Business (Research) Queensland University of Technology. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/112813/

Cumming, T. (2015). Early childhood educators' experiences in their work environments: Shaping (im)possible ways of being an educator? Complicity: An International Journal of Complexity and Education, 12(1), 52-66.

Cumming, T. (2017). Early childhood educators’ well-being: An updated review of the literature. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(5), 583–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0818-6.

Cumming, T., Sumsion, J., & Wong, S. (2015). Rethinking early childhood workforce sustainability in the context of Australia’s early childhood education and care reforms. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 9(2).

Cumming, T., & Wong, S. (2019). Towards a holistic conceptualisation of early childhood educators’ work-related well-being. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 20(3), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949118772573.

Cumming, T., Wulff, E., Wong, S., & Logan, H. (2020). Australia’s hidden hazardous workplaces. Bedrock, 25(1), 16–17.

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR). (2009). Belonging, Being & Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. https://docs.education.gov.au/node/2632.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2019). Occupational skill shortages information. https://www.employment.gov.au/occupational-skill-shortages-information.

Department of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business. (n.d.). Early childhood (pre-primary school) teachers. https://joboutlook.gov.au/Occupation?search=Industry&Industry=P&code=2411.

Early Childhood Australia (Tas) and the Tasmanian Department of Education. (2017). The early years & school age care sectors workforce plan for Tasmania 2017-2020. https://employment.eysac.com.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/05/EYSAC-Workforce-Plan_2.pdf.

Education Council. (2019). Education Council Communique 12 December 2019. http://www.educationcouncil.edu.au/site/DefaultSite/filesystem/documents/EC%20Communiques%20and%20media%20releases/Education%20Council%20Communique%20-%2012%20December%202019.pdf.

Farrell, M., Walker, S., Bower, A., & Gahan, D. (2000). Researching early childhood student teachers: Life histories and course experience. International Journal of Early Childhood, 32(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03169021.

Fenech, M. (2019). Pursuing a social justice agenda for early childhood education and care: Interrogating marketisation hegemony in the academy. In K. Freebody, S. Goodwin, & H. Proctor (Eds.), Higher education, pedagogy and social justice: Politics and practice (pp. 81–96). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fenech, M., Sumsion, J., & Goodfellow, J. (2006). The regulatory environment in long day care: A “double-edged sword” for early childhood professional practice. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 31(3), 49–58.

Fenech, M., Robertson, G., Sumsion, J., & Goodfellow, J. (2007). Working by the rules: Early childhood professionals’ perceptions of regulatory environments. Early Child Development and Care, 177(1), 93–106.

Fenech, M., Waniganayake, M., & Fleet, A. (2009). More than a shortage of early childhood teachers: Looking beyond the attractment of university qualified teachers to promote quality early childhood education and care. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 37(2), 199–213.

Future Tracks. (2019). Upskilling in early childhood education: Opportunities for the current workforce. https://www.futuretracks.org.au/images/downloads/UpskillReport.pdf.

Gibson, M. (2013). ‘I want to educate school-age children’: Producing early childhood teacher professional identities. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 14(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2013.14.2.127.

Gibson, M., McFadden, A., Williams, K. E., Zollo, L., Winter, A., & Lunn, J. (2019). Imbalances between workforce policy and employment for early childhood graduate teachers: Complexities and considerations. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 45(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119885308.

Gibson, M., McFadden, A., & Zollo, L. (2018). Discursive considerations of child care professional experience in early childhood teacher education: Contingencies and tensions from teacher educators. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 39(4), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2018.1458259.

Grant, S., Comber, B., Danby, S., Theobald, M., & Thorpe, K. (2018). The quality agenda: Governance and regulation of preschool teachers’ work. Cambridge Journal of Education, 48(4), 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2017.1364699.

Grant, S., Danby, S., Thorpe, K., & Theobald, M. (2016). Early childhood teachers’ work in a time of change. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 41(3), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911604100306.

Grebennikov, L., & Wiggins, M. (2006). Psychological effects of classroom noise on early childhood teachers. Australian Educational Researcher, 33(3), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216841.

Harrison, C., & Heinrich-Joerdens, S. (2017). The combined Bachelor of Education Early Childhood and Primary degree: Student perceptions of value. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.42.1.01.

Harrison, L. J., Wong, S., Press, F., Gibson, M., & Ryan, S. (2019). Understanding the work of Australian early childhood educators using time-use diary methodology. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 33(4), 521–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1644404.

Irvine, S., Thorpe, K., McDonald, P., Lunn, J., & Sumsion, J. (2016). Money, love and identity: Initial findings from the National ECEC Workforce Study. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/101622/1/Brief_report_ECEC_Workforce_Development_Policy_Workshop_final.pdf.

Jackson, J. (2020). Every educator matters: Evidence for a new early childhood workforce strategy for Australia (p. 12). Paper presented at the Early Childhood Workforce Roundtable: Macquarie University, February.

Jones, C., Hadley, F., & Johnstone, M. (2017). Retaining early childhood teachers: What factors contribute to high job satisfaction in early childhood settings in Australia? New Zealand International Research in Early Childhood Education, 20(2), 1–18.

Jones, C., Hadley, F., Waniganayake, M., & Johnstone, M. (2019). Find Your Tribe! Early childhood educators defining and identifying key factors that support their workplace wellbeing. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 44(4), 326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119870906.

Jovanovic, J. (2013). Retaining early chilong day careare educators. Gender, Work & Organization, 20(5), 528–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2012.00602.x.

Kirk, G. (2020). Gender differences in experiences and motivation in a Bachelor of Education (Early Childhood Studies) course: Can these explain higher male attrition rates? The Australian Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00374-8.

Lazarides, R., Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2020). Teachers’ classroom management self-efficacy, perceived classroom management and teaching contexts from beginning until mid-career. Learning and Instruction, 69, 101346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101346.

Liu, Y., & Boyd, W. (2018). Comparing career identities and choices of pre-service early childhood teachers between Australia and China. International Journal of Early Years Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2018.1444585.

Logan, H., Cumming, T., & Wong, S. (2020). Sustaining the work-related wellbeing of early childhood educators: Perspectives from key stakeholders in early childhood organisations. International Journal of Early Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00264-6.

Loh, J. M. I., Robinson, K., & Muller-Townsend, K. (2020). Exploring the motivators and blockers in second year undergraduate students: An ecological system approach. The Australian Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00385-w.

Mahony, L., Disney, L., Griffiths, S., Hazard, H., & Nutton, G. (2020). Straddling the divide: Early years preservice teachers’ experiences working within dual policy contexts. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120918501.

Manning, M., Wong, G. T. W., Fleming, C. M., & Garvis, S. (2019). Is teacher qualification associated with the quality of the early childhood education and care environment? A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 89(3), 370–415. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319837540.

McKinlay, S., Irvine, S., & Farrell, A. (2018). What keeps early childhood teachers working in long day care? Tackling the crisis for Australia’s reform agenda in early childhood education and care. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(2), 32–42.

Nolan, A., & Rouse, E. (2013). Where to from here? Career choices of pre-service teachers undertaking a dual early childhood/primary qualification. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n1.8

NSW Department of Education. (2018). Early childhood education workforce strategy 2018-2022. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/early-childhood-education/working-in-early-childhood-education/media/documents/NSW_WorkforceStrategy-accessible.pdf.

Nuttall, J. (2018). Engaging with ambivalence: The neglect of early childhood teacher education in initial teacher education reform in Australia. Setting directions for new cultures in teacher education. In C. Wyatt-Smith & L. Adie (Eds.), Innovation and accountability in teacher education (pp. 155-169). The Netherlands: Springer.

O'Connell, M. (2019). One-third of all preschool centres could be without a trained teacher in four years, if we do nothing. https://theconversation.com/one-third-of-all-preschool-centres-could-be-without-a-trained-teacher-in-four-years-if-we-do-nothing-120099.

OECD. (2006). Starting strong II: Early childhood education and care. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

OECD. (2012). Starting strong III: A quality toolbox for early childhood education and care. OECD Publishing:. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264123564-en.

OECD. (2019). Good practice for good jobs in early childhood education and care: Eight policy measures from OECD countries. http://www.oecd.org/els/family/Good-Practice-Good-Jobs-ECEC-Booklet_EN.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2019.

Pascoe, S., & Brennan, D. (2017). Lifting our game: Report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools through early childhood interventions. https://www.education.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1159357/Lifting-Our-Game-Final-Report.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2018.

Press, F., Wong, S., & Gibson, M. (2015). Understanding who cares: Creating the evidence to address the long-standing policy problem of staff shortages in early childhood education and care. Journal of Family Studies, 21(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1020990.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2014). 2013 Early childhood education and care workforce review. http://www.educationcouncil.edu.au/site/DefaultSite/filesystem/documents/Reports%20and%20publications/Publications/PwC%20ECEC%20Workforce%20Review,%20FINAL,%2013%20Nov%202014.pdf.

Productivity Commission. (2011). Early childhood development workforce research report. http://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/education-workforce-early-childhood/report/early-childhood-report.pdf.

Productivity Commission. (2014). Chilong day careare and early childhood learning: Productivity Commission inquiry report. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/chilong day careare/report/chilong day careare-overview.pdf.

Queensland Department of Education and Training. (2020). Early childhood education and care: Workforce action plan 2016–2019. https://earlychildhood.qld.gov.au/careersAndTraining/Documents/workforce-action-plan-16-19.pdf.

Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. G. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660500480290.

Richardson, P.W., Fleet, A., Watt, H.M.G. & Waniganayake, M. (2011). What motivates early childhood teachers to undertake a teaching career? Paper presented at the AARE Annual Conference, Hobart, Australia.

Rosa, E. M., & Tudge, J. (2013). Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory of human development: Its evolution from ecology to bioecology. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(4), 243–258.

Rowan, L., Mayer, D., Kline, J., Kostogriz, A., & Walker-Gibbs, B. (2015). Investigating the effectiveness of teacher education for early career teachers in diverse settings: The longitudinal research we have to have. The Australian Educational Researcher, 42(3), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-014-0163-y.

Shah, C. (2015). Demand and supply forecasts for educators in Victorian funded kindergarten services, 2016–2020. Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Education and Training.

Social Research Centre. (2014). 2013 National early childhood education and care workforce census. www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2015/nwc_national_report_final.pdf.

Social Research Centre. (2017). 2016 Early childhood education and care national workforce census. https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/2016_ecec_nwc_national_report_sep_2017_0.pdf.

Standing Council on School Education and Early Childhood [SCSEEC]. (2012). Early years workforce strategy: The early childhood education and care workforce strategy for Australia 2012-2016. https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/early_years_workforce_strategy_0_0_0.pdf.

Sumsion, J. (2000). Rewards, risks and tensions: Perceptions of males enrolled in an early childhood teacher education programme. Asia - Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 28(1), 87–100.

Sumsion, J. (2002). Becoming, being and unbecoming an early childhood educator: A phenomenological case study of teacher attrition. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(7), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00048-3.

Sumsion, J. (2003). Rereading metaphors as cultural texts: A case study of early childhood teacher attrition. The Australian Educational Researcher, 30(3), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216798.

Sumsion, J. (2004). Early childhood teachers’ constructions of their resilience and thriving: A continuing investigation. International Journal of Early Years Education, 12(3), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966976042000268735.

Sumsion, J. (2007). Sustaining the employment of early childhood teachers in long day care: A case for robust hope, critical imagination and critical action. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 35(3), 311–327.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2004). The effective provision of pre-school education (EPPE) project: Findings from pre-school to end of key stage. https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=3155&context=sspapers. Accessed 17 Jan 2018.

Tayler, C. (2016). The E4Kids study: Assessing the effectiveness of Australian early childhood education and care programs. https://education.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2929452/E4Kids-Report-3.0_WEB.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2019.

Thorpe, K., Boyd, W., Ailwood, J., & Brownlee, J. (2011). Who wants to work in child care?: Pre-service early childhood teachers’ consideration of work in the chilong day careare sector. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 36(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911103600114.

Thorpe, K., Jansen, E., Sullivan, V., Irvine, S., McDonald, P., Thorpe, K., & The Early Years Workforce Study. (2020). Identifying predictors of retention and professional wellbeing of the early childhood education workforce in a time of change. Journal of Educational Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09382-3.

Thorpe, K., Millear, P., & Petriwskyj, A. (2012). Can a chilong day careare practicum encourage degree qualified staff to enter the chilong day careare workforce? Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 13(4), 317–327. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2012.13.4.317.

Totenhagen, C. J., Hawkins, S. A., Casper, D. M., Bosch, L. A., Hawkey, K. R., & Borden, L. M. (2016). Retaining early childhood education workers: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(4), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2016.1214652.

Victorian Department of Education and Training. (2019). Early childhood scholarships and incentives program guidelines. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/childhood/professionals/profdev/ECSIP%20guidelines%20August%202019.pdf.

Watson, L. (2006). Pathways to a profession: Education and training in early childhood education and care. Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training.

Whitebook, M., Phillips, D., & Howes, C. (2014). Worthy work, STILL unlivable wages: The early childhood workforce 25 years after the National Child Care Staffing Study. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley.

Zavelevsky, E., & Lishchinsky, O. S. (2020). An ecological perspective of teacher retention: An emergent model. Teaching and Teacher Education. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102965.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In page 11, the sentence “However, it is only through large-scale studies, such as Richardson and Watt (2006) with 1653 participants, that we are able to discern how widespread these experiences are, and test the robustness of theories developed” is updated as “However, it is only through large-scale and longitudinal studies, such as the continuing ‘FIT-Choice’ (Factors Influencing Teaching Choice; www.fitchoice.org) project of Watt and Richardson which tracks the trajectories of 2007 future teachers from their entry to teacher education until their mid-career teaching (see for retention rates, Lazarides, Watt, & Richardson, 2020), that we are able to discern how widespread these experiences are, and test the robustness of theories developed.” and the reference “Lazarides, R., Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P.W. (2020). Teachers’ classroom management self-efficacy, perceived classroom management and teaching contexts from beginning until mid-career. Learning and Instruction, 69, 101346. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101346.” is included. The blind version of the Electronic Supplemetary Material has been updated with the correct version.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fenech, M., Wong, S., Boyd, W. et al. Attracting, retaining and sustaining early childhood teachers: an ecological conceptualisation of workforce issues and future research directions. Aust. Educ. Res. 49, 1–19 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00424-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00424-6