Abstract

It is commonly believed that the doctorate prepares students for academic careers. While there is wide ranging literature about the development of doctoral students as researchers, preparation for the other aspects of academic careers, e.g. teaching, is mostly absent from the discussion. This qualitative longitudinal study investigated the shift from doctoral identities to academic identities using narrative inquiry. It examined the narratives of 15 doctoral students from two large Australian universities, who were approaching thesis submission and who aspired to academic employment. Two contrasting stories illuminated in-depth accounts of how academic identities were developed and experienced. Students defined their identities and assessed their academic development in relation to their perceived ‘market value’ in academia. To increase their employability, they engaged in university teaching and focused on strategic networking. Students regarded researcher development as the main focus of the doctorate as being insufficient for an academic career. This paper argues that doctoral education needs to facilitate student agency, encourage synergies between teaching and research, and support non-academic work experiences to strengthen researcher identity development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is commonly believed that the doctorate prepares students for academic careers, and, in fact, many still do want an academic career despite dire job prospects (Bexley et al. 2012). However, evidence shows that the doctorate is not as well designed for this purpose as is widely assumed (Brew et al. 2011; Greer et al. 2016). This paper investigated doctoral students’ shifts from doctoral to academic identities and their perceptions of their academic identities as they approached thesis submission and aspired to academic employment. In Australia, the doctoral research degree takes on average 3–4 years and culminates in a written thesis of about 100,000 words. Most Australian universities do not mandate an oral examination or coursework although some have adopted one or both of these practices. However, higher degree research workshops and seminars may be offered to students. This paper finds that students actively seek academic work experience and strive to develop more than research skills to improve their employability in academia. Bluntly put, the doctorate is not enough to secure an academic job. This paper reveals teaching practice as being one critical factor to students’ ability to imagine possible academic selves although teaching practice is not well integrated nor adequately supported in Australian doctoral programs. The findings contribute to a nuanced understanding of what facilitates academic identity formation in the doctorate and questions whether the current doctorate adequately prepares students if they wish to pursue academic careers. It aims to inform higher degree research support and to stimulate a reconsideration of the ways that research degrees develop future academics. While this paper is based on Australian students the significance of the findings reach beyond Australia and apply to any similar doctoral and academic system.

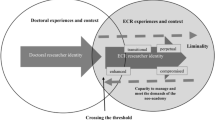

The section below presents a visual diagram of the literature and theoretical conceptualisations that inform this research. The section that follows describes the participant sample and the methodology employed in identifying two contrasting stories of identity development in the doctoral experience. These two cameos combined with experiences of the other participants are discussed in light of other research to illustrate the argument of this paper. It concludes with implications for practice.

Literature review

This paper is situated within the literature about the researcher development of doctoral students. Specifically, it discusses how the nature of academic practice, changing academic roles, and the current academic employment context contribute to the understanding of how doctoral students increasingly and gradually assume academic identities. Figure 1 presents an overview that helps to locate this paper in this current research. The different strands of literature are positioned to visualise the argument of the paper. The discussion of doctoral identities (on the left) positions students as being and becoming researchers, while the right-hand side sees students in the enactment (doing) of future academic identities. This is a necessarily abstracted and even idealised representation of complex processes in the identity development of doctoral students. Doctoral students are commonly expected to gradually move from left to right, taking into account personal circumstances and professional aspirations. However, this movement may not be as smooth or as uniform as this simplified overview of the literature makes us believe, or may not occur at all. Narrative inquiry is used as a methodology to create a dialogue between the bodies of literature, and hence, it is illustrated as a background circle that connects both sides of the figure.

Doctoral student identities

The doctoral experience is commonly known to be a challenging and simultaneously exhilarating journey. Doctoral student identities are a patchwork “enacted ‘in the gaps’ of everyday life” (Barnacle and Mewburn 2010, p. 437). Students reconcile various identities on a daily basis (e.g. care responsibilities, academia or industry employment) while finding their place in academia. Their life experiences and career aspirations significantly impact their development. This is broadly described as identity-trajectory by McAlpine (2012).

Doctoral identity development is generally conceptualised as a sociocultural learning process of becoming an independent researcher. Theoretical constructs, such as community of practice (Lave and Wenger 2002), community of learning (Pearson and Brew 2002), developmental networks (Baker and Lattuca 2010), and learning networks (Barnacle and Mewburn 2010), help explain the socialisation processes of doctoral students. They describe how doctoral students move from novice to expert via various social and community settings embedded in departmental and institutional structures (Boud and Lee 2005).

Recent research provides insights into how researcher identities are formed during the doctorate as well as highlights significant events, activities and structures that enable students to identify as emerging researchers (Mantai 2017; McAlpine et al. 2009; Sinclair et al. 2013; Sweitzer 2009; Turner and McAlpine 2011). This literature highlights how an institutional focus on research outputs (Rond and Miller 2005) dominates the doctoral experience. It primarily positions the student as a research student and, while recognising students’ involvement in other (often paid) activities alongside their study, largely neglects emerging academic identities. Recent literature raises concerns about doctoral students’ readiness for professional employment, and proposes reshaping doctoral training to include more generic skill development to suit diverse employment settings (Walker et al. 2009).

Academic identities of doctoral students

Although doctoral graduates increasingly choose work outside academia, many graduates aspire to academic work (Edwards et al. 2011) and imagine what Markus and Nurius (1986) describe as possible selves. Possible selves are basically images of oneself in the future. These can be positive (those to aim for) and negative (those to avoid). Markus and Nurius (1986) postulate that individuals’ motivations and actions today accord to how they imagine themselves in the future. The concept of academic possible selves has been previously operationalised by Thiry et al. (2015) as knowledge about career options, beliefs about possible careers, and career preparation among doctoral students. Today’s academic employment market is highly casualised, with few continuing positions (Bexley et al. 2012). Besides, academic roles are changing, becoming increasingly diverse and now encompass research, tertiary teaching, project management, curriculum design, community engagement, entrepreneurship, and more (Boud and Brew 2013). An academic role involves roughly 40–60% of activities related to teaching; this is higher for casuals (Golde and Dore 2001; McInnis 2000). This can add up to over 30 h per week of wide-ranging activities related to teaching (Pitt and Mewburn 2016). Yet, teaching development is rarely integrated in the doctorate and academic development, including teaching, is rarely taken up post-doctorate (Brew et al. 2011).

In contrast to the research-focused Researcher Skill Development framework (Willison and O’Regan 2013), the Statement on Skills Development for Research Students by the Council of Australian Deans and Directors of Graduate Studies (in Gilbert et al. 2004) includes generic skills for doctoral students. The last point is professional development including tertiary teaching and developing employment and career opportunities. However, research shows that the doctorate inadequately prepares for academic (Brew et al. 2011) and industry employment (Walker et al. 2009).

In sum, research on the lived doctoral experience discusses issues pertaining to research and researcher development (lack of support, problematic supervision, imposter syndrome, writing difficulties), but less so students’ engagement in or disengagement from academic practices (learning and teaching, career planning, organisational work, service and committee work, supervising and mentoring students, and so on). This paper identifies teaching and supervising students as academic practices that can transcend doctoral identities from research student to academic and create positive academic selves.

Identity-trajectories and possible selves

The concept of identity-trajectory (McAlpine 2012) helps to explain doctoral student identity development towards academic identities as embedded in personal lives and experiences. The concept of identity is a “vexed question” (Clegg 2008, p. 329) with multiple definitions. This paper uses identity in relation to doctoral doing, i.e. the more one engages in academic work, the more strongly one identifies with being an academic (McAlpine et al. 2009). Academic identities are informed by roles and responsibilities, which include research activities (shaping researcher identities) alongside non-research practices, teaching and administration (Vitae, 2010).

Positioning the student as an active agent in the development of academic identity, this paper applies the notion of identity-trajectory, which highlights the role of personal circumstances in directing career opportunities over time and space (McAlpine 2012; McAlpine et al. 2014). Narrative research presents widely accepted methodology to investigate the concept of identity, as stories of identities make the abstract graspable (Connelly and Clandinin 1990). This paper utilises narrative inquiry based on the belief that people’s identities are of discursive nature, constantly evolving, and expressed through stories of their experiences (Connelly and Clandinin 1990; Sfard and Prusak 2005).

Students’ stories of activities undertaken during the doctorate, in order to develop professional identities and increase employability, relate to concepts of opportunity structures and horizons for action (Hodkinson and Sparkes 1997). Opportunity structures, a key construct of identity-trajectory, explain students’ perceived future career possibilities. Horizons for action define viable career options given personal circumstances and degrees of freedom in acting towards such opportunities. These constructs closely relate to possible selves. The latter adds the social context as a critical factor that shapes and influences possible selves. If a possible self and strategies to achieve it feel well aligned with one’s social identities (e.g. ethnicity, gender, class) one is more motivated to work towards this possible self. Misalignment leads to perceived conflict with one’s identities (Oyserman et al. 2006). In bringing these concepts together, this paper examines how students view, develop and articulate their professional, specifically academic, identities during their doctorate. Students’ narratives and perceptions serve to understand the shift from being a doctoral student to an academic.

Participants

Appropriate ethics approval was obtained for this research (Reference: 5201300597). The Call for Participants was circulated to doctoral students at both universities through research support staff and departmental administrators. Interested candidates could register their willingness to participate in interviews and indicate their availability via an online survey. Participation incentives were offered in the form of a $20 gift card for each interview. Fifteen doctoral students from two research-intensive universities in Australia were interviewed in year one or two of their doctorate, and again one and a half years later. As the doctoral experience is marked by ups and downs, it was important to capture not only students’ initial enthusiasm at the start of their doctorate but also students’ lived experience close to submission, often the most challenging stage of the doctorate (Grover 2006). The same open interview questions were asked each time inviting participants to share their doctoral experience with a focus on their researcher development. The group reflected the diversity of the Australian doctoral student population but I do not claim this sample to be representative (see Table 1). All but one participant expressed a desire for academic employment post-doctorate but were open to outside opportunities given the difficult academic job market. All names in this paper are pseudonyms for the purpose of de-identification.

Data analysis

Narrative inquiry as utilised in sociocultural research on learning reveals stories as constructions of identity, “individually told […] products of a collective storytelling” (Sfard and Prusak 2005, p. 14). As McCormack (2004) states, stories are both a mirror revealing ourselves and a window revealing others. This paper embraces the idea of a narrative-defined identity and locates identity-building in stories of lived experience (Connelly and Clandinin 1990). It views identity-making as a communicational practice, a discursive as opposed to a fixed construct, and as stories of our future possible selves. As such, identity is ever-changing, never complete, and subject to social and cultural influences (Sfard and Prusak 2005). To capture this complexity, two types of thematic analysis, adapted from Saldaña (2015), were conducted: (a) thematic coding and (b) mapping of events to students.

Thematic coding

Applying the six-phase thematic analysis approach by Braun and Clarke (2006), several themes pertaining to doctoral identities emerged (Mantai 2017). A key theme of this research is that doctoral students do not only identify as researchers but increasingly see themselves as academics in the course of the doctorate. For this paper, all coded text relating to the theme identity development was revisited. In line with narrative inquiry the purpose is to preserve participants’ voices to convey an authentic account of how doctoral students discuss their development as academics, so lengthy quotes are used to keep narratives intact.

Mapping of events to students

Building on Thiry et al.’s work (2015), this paper operationalises possible selves through events and stories reported by doctoral students. Narratives have two foci: events and experience (Andrews et al. 2013). Students report stories of critical events that enable positive or negative possible selves. Positive events, for instance, include social support, skill development opportunities, publications, and helpful supervision, while negative events include juggling research and paid work, time pressures, financial troubles, administrative, and technical issues. In this paper, such events are intensifiers (Winchester-Seeto et al. 2014) that magnify difficult or reveal uncomplicated doctoral experiences. In order to identify representative portraits, all events reported by doctoral students (events that had occurred during the doctorate and which were perceived to have impacted their doctoral experience and possible selves positively or negatively) were mapped to students in a researcher-constructed matrix (Table 2 shows a simplified version). While re-reading interview transcripts reported events were listed on the left (bold print) as they emerged, categorised either in the positive or negative experience category, with an X indicator linking experiences to participants.

This approach retained students’ individual contexts and highlighted personal life circumstances while structuring the data for analytical purposes. The matrix proved to be a useful exercise as it enabled comparison of doctoral experiences. Where students reported a higher proportion of negative events, they expressed dissatisfaction with their doctorate and struggled to view or imagine themselves as academics. Where events showed support and reassurance, students articulated overall satisfaction, personal and professional confidence. This data analysis approach identified two contrasting doctoral experiences that represent the range of participants’ academic identity development experiences. Below are the stories of full-time students Ann and Jacob, presented as researcher-constructed cameos (McAlpine et al. 2014). While this approach sidelines the stories of other research participants, the decision to highlight two contrasting voices is necessary to clearly illustrate the point that for some students gaining academic work experience, alongside doctoral research, benefits their researcher development and helps imagine academic possible selves.

Findings

Ann’s story

Ann’s doctorate in Humanities is marked by struggles and tensions between her social and academic needs. She starts off working at home but soon feels lonely and craves social interaction, so she takes up an office space on campus. She says her supervisors were often unavailable and cancel meetings, do not respond to emails, or are away on long service leave. Ann lacks direction and is frustrated. After signing up for a lunchtime reading and discussion group, her support network grows. In her third year, her department is disestablished unexpectedly. This causes major disruption to her progress and confidence:

It felt like we were a bit stranded. And we were in a way, because we did not have [reading group] sessions any more. The academics seemed quite palpably stressed and no one really knew what was going on, or no one told the PhD students what was really going on, so we’re all just floating around trying to work on our own projects without any sense of being a part of any thing.

With reluctance Ann changes university and supervisor, resulting in multiple losses: time, energy, social networks, top-up scholarship. She also has to give up a teaching opportunity. She struggles to settle in as the new department follows a different interpretation of the discipline, which challenges the views she has previously adopted. This puts enormous pressure on her progress. She is concerned about being behind on writing, not yet having publications, with no teaching experience. Now somewhat settled at the new university, she feels ‘rushed’ through the doctorate and does not have time to invest in friendships or professional networks. She admits this is detrimental to her future job opportunities. With resignation she explains: ‘I do not have the time to be a new student’. Ann mourns the loss of an immediate support network that she had in her old office. She describes her new office as isolating, ‘hostile’, ‘unwelcome’, making her feel ‘like a stranger’. She looks forward to Fridays when she meets her peers from the previous institution for Shut Up and Write at a local café that is ‘quite homely’. This writing group is her main support group and she values it dearly. These events have not only impacted progress but also development: ‘my confidence has been knocked around quite a bit’. With noticeable sadness she shares a lesson learned: ‘You’re the only one who really has your project’s best interest at heart, and you really have to be your own resource, you have to make your own opportunities’.

Jacob’s story

Jacob’s doctorate is marked by optimism and tells a story of support, enjoyment, passion for teaching, as well as personal and professional development. He is in Science but identifies as a ‘human researcher’ and does not work in a lab group setting. Despite initial setbacks, including a relationship break-up and health issues, Jacob starts his doctoral journey with close friends from undergraduate studies. He prides himself on being a ‘people’ person and a confident speaker. He wins a 3 Minute Thesis competition in his faculty. Rather than participate in doctoral seminars or workshops, Jacob prefers to hang out with his friends. His support network consists of a group of close friends supervised by the same academic who study and live together. Jacob explains how they all like to compete, but also celebrate each other’s successes. Jacob repeatedly states ‘teaching is my favourite part of the doctorate’, saying he learns best through teaching others. ‘I feel like my teaching is also an incredibly important part of my academic development’. After being invited to speak on a panel and presenting at an international conference, he feels academics in his department ‘treat him differently’, with more respect. Jacob is helping two Honours students with fieldwork, research participant recruitment and writing. Supervising students is a professional development opportunity for Jacob. He explains his colleagues ‘see me as an academic now’ and that makes him feel ‘more academic’, ‘more professional’ and like he has ‘earned that’. He also feels like a stronger researcher after mastering statistical analysis. As he describes it, he plays by the rules of academia by focusing on ‘publishing and conferencing’, and is strategic in his interactions and activities. Hoping to build a ground for job opportunities post-doctorate he makes himself ‘available to help superior people in the event that I need someone in the future’. Jacob is the only participant who speaks with confidence about positioning himself successfully for a post-doctoral fellowship. Overall he feels ‘very content, cautiously optimistic’ about his doctorate, looking forward to ‘where the next portion of my life will be’.

Developing an academic identity: Ann versus Jacob

In their second year, Ann and Jacob tell a similar story of how they think they will become researchers: through publishing. A track record of publications and successful conference presentations provide evidence of acceptance and recognition as a peer by the research community. Achieving this is their primary goal. Ann views collaboration and networking as an opportunity for external validation but also to build supportive relationships. She comments:

It’s really important for you to build networks and establish yourself as a researcher. It’s an actual skill that you learn as a researcher, how to network with people, how to collaborate with people. You learn how to present in front of an audience, you learn how to be a researcher.

In the first interview, Ann adds that participation in research groups is expected in her department because “you’ll be part of the research community”. In regard to future employment, Jacob and Ann hope to become more independent, more autonomous, and more professional in the process. Both hope to find work in academia post-doctorate, but realise the scarcity of positions and hence, make alternate plans: Ann in industry, and Jacob in further study.

Both students report growing in confidence as researchers as they capitalise on external recognition over a 1-year period. In his second interview, Jacob attributes his confidence to his growing publication track record:

I’ve got a publication coming out and I’m working on two others, so that is establishing myself in the future to pursue a post-doctoral fellowship. Having two other Honours students; the one from last year is about to publish, so that’s another one for me. I’ve gone into a number of quite prestigious conferences, too. I guess all this is to establish myself, make it likely, that I will be able, to achieve a post-doctoral fellowship.

Although Jacob seems naturally more confident than Ann, praising his “people and communication skills”, both show initial insecurity that is typical of people learning new skills. Ann says: “I feel like it’s an apprenticeship and I’m an apprentice researcher. What does a doctoral student have to offer, at this stage anyway? I still feel quite junior”. Her research proposal approval and speaking with colleagues on a panel at her first international conference were a “formal demarcation”:

[It is a] formal acknowledgement that you’re on the right track. For me at least, it gave me that boost to be like ‘okay, I’m not just floundering around here’. I have some purpose and I know what I’m researching. All of those more formal parts of academics where you’re contributing to writing papers and giving papers. That does impact and shape the way that you view yourself.

At the conference she gains recognition as a peer researcher due to “a different environment”, she says, “the hierarchies might not have been as set, everything was a bit new for everyone”.

Jacob describes himself as a strong communicator, but admits being very anxious about his first conference presentation. Its success gives him a confidence boost and he describes himself as “a stronger researcher” a year later, despite struggling with writing difficulties.

Teaching (including tutoring) and helping students learn is a reoccurring theme in participants’ stories. Jacob comments on his love for teaching in the first interview, saying “there’s no better feeling than seeing a person’s face light up when they learn something. I love that feeling, that elation when they’ve learnt”. A year later he attributes significant value to his teaching experience, describing it as academic development of himself, and resents that it is undervalued:

What gets drilled into me by academics is ‘publish or perish’. And you hear it everywhere: you need to go talk, you need to write, blah, blah. But the teaching I love… I feel like my teaching is also an incredibly important part of my academic development. I know that I’ve learnt far more through teaching than I ever did in undergrad. So I do think while publication and conferencing is super-duper important, your research and learning how to do statistics, whilst also teaching, I think, is just as important.

On the topic of supervising Honours students in their research, he adds:

I had an academic in the last year who was really struggling with one of their students, so they asked, because I was working for them as a teacher, as one of the demonstrators, ‘Oh could you just see how they’re going?’ And we worked out what the issue was and the student ended up getting first class Honours. It was a nice feeling and then I got an extra class to teach … I went out of my way to help, and they made sure I had an opportunity to develop as a teacher. I appreciated that.

Ann, in contrast, laments not getting another opportunity to gain teaching experience:

I felt like it [teaching] would be really important if I wanted to get a job in academia, you need to have that experience. And for your own work [research] it’s really good to teach because it really solidifies your knowledge, if you have to clarify what you know and teach undergraduates who are new to the field. It’s really helpful for your own work but I already feel quite set back, I just can’t see that I’d be able to take on teaching.

Echoing the need for external recognition in developing a professional identity, Jacob aptly describes the importance of being seen as an academic by other colleagues. He talks about how they view and treat him differently in his third year:

I’m certainly feeling a lot more confident, and in the least big-headed way I’m feeling more like an academic now. Actual academics go, ‘Oh could you help me out with this?’ And of course I’ll come and help, or a last-minute tutorial … that wouldn’t have been dumped in my lap a year ago, because the superior people wouldn’t have thought I was up to it. So that is a nice feeling, I feel like I’ve earned that.

Ann and Jacob talk about feeling like an academic, a researcher as well as a professional. While both feel a stronger identification as researchers due to research practice gained over the year, the way they perceive and define their possible academic selves and identities differs. Ann’s perception of herself as an academic is threatened by disruptions during her doctorate and a lack of teaching experience. She regards herself as a researcher in relation to her small research community. As it falls apart her sense of academic identity is challenged, which is expressed in her insecurity and frustration about completion and career options. She feels rushed towards completion, not feeling ready to call herself an academic. In contrast, Jacob’s identification as a researcher is fueled by his experience and ability to present and publish his research. More importantly, his teaching experience earns him confidence and recognition as an academic. As opportunities increase so does his perceived development as an academic.

What facilitates the shift from doctoral to academic identities?

Ann and Jacob define academic identity in terms of their own employability. They develop possible academic selves by increasing their “market value” through engaging in academic practices such as teaching and supervising Honours students. The two stories highlight two approaches to feeling more employable, in Jacob’s words “more academic”: capitalising on various academic work experiences, professional relationships and networks. Table 3 below provides a summary of both students’ experiences relating to these aspects.

How do these findings relate to the larger participant sample? Research participants suggest their learning, and hence, their personal and professional development, is closely linked to teaching or mentoring others for two reasons. Firstly, the ability to explain complex concepts to others helps cement one’s own learning. Doctoral students claim that teaching develops their confidence and is often a source of satisfaction. Secondly, helping others is payback for help received as Honours students. The relationship between teaching and learning is widely acknowledged in education but is overlooked in doctoral education as a site of researcher and academic development. Students express disappointment with the extent of learning about research and other academic tasks achieved before submission, as they assess their employability:

The sad thing is that I’ve realised that I will not be able to do a PhD that is my best work, and I will not be able to learn all of the stuff that I was really hoping to learn. I will need to cut back to a more realistic level. And that’s a bit disappointing. (Ellen)

The second theme is the context of today’s academic job market. Students assess their employability in comparison with fellow doctoral students (mainly comparing their publication track record) and against expectations of academic roles mandated by institutions and media. Some students consider avenues to increase their market value, often focusing on honing their teaching skills. Others talk about turning to industry or private education providers. Students seek developmental activities or not, depending on how they view their readiness for an academic career.

My supervisor said, ‘Look, to be completely honest, there’s not a lot of work in academia. And you have to take into account your age’. He didn’t say that, but he said, ‘You have to take into account a lot of factors. Perhaps you need to think outside the box.’ (Annabelle)

Once you get to the end of your PhD, you have your thesis but you don’t necessarily have something to go on to. I may get a job. I may stay in academia. I don’t know what I’m going to do. (Nicole)

I saw PhD students who are sacrificing their [current industry] jobs because they have committed to this unproductive journey [PhD]. They’re definitely losing money; they’re losing prospects in their earlier job [in their home country], so after they finish the PhD they have to start a new thing. (Mitch)

Students’ agency and motivation to engage in strategies that align with their identity have previously been identified as critical factors in enabling academic possible selves and increasing personal influences on future intentions (horizons for action) with similar cohorts (e.g. McAlpine et al. 2014; Turner and McAlpine 2011). Finally, participation in research groups and active engagement with local and international research communities is articulated as being critical to academic learning. Sweitzer (2009) described this phenomenon as developmental networks based on a longitudinal study of 12 doctoral students. Such professional connections and relations are highly valued when seeking employment:

The worst thing that you can do as a PhD student is shoot yourself in the foot. Science is obviously massive about communication; that’s externally as well as internally. So you need to be able to form collaborations externally, in your lab, and be a people person. My supervisor would look out for me; if I was needing [a job], he would sort me out; he would get me involved. I think everyone else likes me and knows I work hard, and obviously they know I fit into the daily workings of the lab. They would probably rather have me than someone they have a CV from. But, obviously, it’s a really competitive lab. (Karl)

In summary, doctoral students engage in various developmental and networking opportunities not related to doctoral research to gain a competitive advantage when it comes to post-doctoral employment. As all but one participant preferred an academic career, such opportunities are sought in their immediate environment, their universities. They value not only the additional work experience that they can add to their CVs but also the networks and relationships that they form. Collectively, these create academic possible selves and help doctoral students to move from students to researchers and academics. Interestingly, teaching experience surfaces as a very effective way of achieving this upgrade in status, as perceived by students themselves and by their colleagues.

Discussion and Conclusion

The desire to learn drives personal and professional development in the doctorate. Daily activities (lab work, reading, writing), formal activities (presenting and publishing) and relationships with others are prominent aspects of becoming and feeling like a researcher (Mantai 2017; McAlpine et al. 2009). This paper has presented an account where teaching practice is adding immediate and perceived future value for doctoral students and their researcher identity development. Teaching here emerges as an important but neglected site of academic work and identity formation (Golde and Dore 2001; Greer et al. 2016; Jepsen et al. 2012). Although doctoral graduates are expected to develop skills in tertiary teaching, development opportunities are not formally offered or facilitated in Australian research education. Teaching creates new opportunity structures and enables possible academic selves through providing academic work experience and extending academic networks and relationships. In line with identity-trajectory (McAlpine 2012), doctoral students in this study reported actively seeking teaching opportunities, through colleagues or supervisors, to increase their academic market value. Capitalising on professional relationships is how students extend their horizons for action (Hodkinson and Sparkes 1997; McAlpine 2012; McAlpine and Emmioğlu 2015). The research—teaching nexus is notoriously difficult to measure and substantiate; however, the findings in this paper showed a very real connection and valuable synergies between teaching and researcher identities for doctoral students’ academic identity development.

However, students should carefully consider if teaching is indeed beneficial and worthwhile in their particular contexts, and explore the various ways of engaging with academic practice and community. Given that the Australian doctorate is research-focused, students need to be proactive in seeking teaching opportunities and in balancing research with teaching. Some students teach to increase their employability, but the investment can increase stress and anxiety (Greer et al. 2016; National Union of Students 2013), especially if the students feel exploited as (cheap) labour (National Union of Students 2013).

The narratives presented here echoed discussions of gender related differences in academic identity construction (Huang 2012; Peterson 2014). Female students are reported to undermine their capabilities, more often experience the imposter syndrome (Clance and Imes 1978) and experience lower levels of satisfaction (Gardner 2008). As in other research (e.g. Oyserman and Fryberg 2006), gender, age, nationality and access to role models and opportunities, and any combinations of these, emerge as limiting or conflicting factors to possible selves. Doctoral students are active agents in their own academic practice development (Mantai 2017); however, agency is constrained by disciplinary, institutional structures and social status, as are possible selves (Markus and Nurius 1986). If Ann had not actively engaged in creating her personal social structures, her doctorate may well have been a story of attrition. Agency deserves more recognition and targeted support for academic identities to be effectively developed during the doctorate.

Finally, the paper has highlighted the importance of feeling like an academic during doctoral study in order to promote academic possible selves and readiness to face the challenges and pressures in doctoral and academic systems similar to Australia. In the context of a highly uncertain and casualised academic job market, students perceived the doctorate as being insufficient to develop their academic and professional identities. In the light of this research, apart from supporting positive learning experiences during the doctorate, doctoral support needs to incorporate opportunities to learn and to experience academic and general professional practice (whether teaching or other academic practice), mobilise student agency in actively mapping and co-designing their developmental journeys and more vigorously connect students with academic and non-academic mentors and role models.

References

Andrews, M., Squire, C., & Tamboukou, M. (2013). Doing narrative research. London: Sage.

Baker, V. L., & Lattuca, L. R. (2010). Developmental networks and learning: Toward an interdisciplinary perspective on identity development during doctoral study. Studies in Higher Education,35(7), 807–827.

Barnacle, R., & Mewburn, I. (2010). Learning networks and the journey of “becoming doctor”. Studies in Higher Education,35(4), 433–444.

Bexley, E., Arkoudis, S., & James, R. (2012). The motivations, values and future plans of Australian academics. Higher Education,65(3), 385–400.

Boud, D., & Brew, A. (2013). Reconceptualising academic work as professional practice: Implications for academic development. International Journal for Academic Development,18(3), 208–221.

Boud, D., & Lee, A. (2005). “Peer learning” as pedagogic discourse for research education. Studies in Higher Education,30(5), 501–516.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology,3(2), 77–101.

Brew, A., Boud, D., & Un Namgung, S. (2011). Influences on the formation of academics: The role of the doctorate and structured development opportunities. Studies in Continuing Education,33(1), 51–66.

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice,15(3), 241–247.

Clegg, S. (2008). Academic identities under threat? British Educational Research Journal,34(3), 329–345.

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher,19(5), 2–14.

Edwards, D., Bexley, E., & Richardson, S. (2011). Regenerating the academic workforce: The careers, intentions and motivations of higher degree research students in Australia: Findings of the National Research Student Survey (NRSS). Higher Education Research.

Gardner, S. K. (2008). Fitting the mold of graduate school: A qualitative study of socialization in doctoral education. Innovative Higher Education,33(2), 125–138.

Gilbert, R., Balatti, J., Turner, P., & Whitehouse, H. (2004). The generic skills debate in research higher degrees. Higher Education Research & Development,23(3), 375–388.

Golde, C. M., & Dore, T. M. (2001). At cross purposes: What the experiences of today’s doctoral students reveal about doctoral education. Philadelphia: Pew Charitable Trusts.

Greer, D. A., Cathcart, A., & Neale, L. (2016). Helping doctoral students teach: Transitioning to early career academia through cognitive apprenticeship. Higher Education Research & Development,35(4), 712–726.

Grover, V. (2006). How am I doing? Checklist for doctoral students at various stages of their program. Decision Line,37(2), 24–27.

Hodkinson, P., & Sparkes, A. C. (1997). Careership: A sociological theory of career decision making. British Journal of Sociology of Education,18(1), 29–44.

Huang, C. (2012). Gender differences in academic self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education,28(1), 1–35.

Jepsen, D. M., Varhegyi, M. M., & Edwards, D. (2012). Academics’ attitudes towards PhD students’ teaching: Preparing research higher degree students for an academic career. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,34(6), 629–645.

Kiley, M., & Wisker, G. (2010). Learning to be a researcher: The concepts and crossings. Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (2002). Legitimate peripheral participation’ in Communities of Practice. In R. Harrison (Ed.), Supporting lifelong learning: Volume 1—Perspectives on learning (pp. 111–126). London & New York: Routledge Falmer.

Mantai, L. (2017). Feeling like a researcher: experiences of early doctoral students in Australia. Studies in Higher Education, 42(4), 636–650.

Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist,41(9), 954.

McAlpine, L. (2012). Identity-trajectories: Doctoral journeys from past to present to future. Australian Universities’ Review,54(1), 38–46.

McAlpine, L., & Åkerlind, G. (2010). Becoming an academic. Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=de&lr=&id=9ZhiAQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=becoming+an+academic&ots=T0gQ_WCoGe&sig=npzj91ewUqcgn6WKH8cg202Db5E.

McAlpine, L., Amundsen, C., & Turner, G. (2014). Identity-trajectory: Reframing early career academic experience. British Educational Research Journal,40(6), 952–969.

McAlpine, L., & Emmioğlu, E. (2015). Navigating careers: Perceptions of sciences doctoral students, post-PhD researchers and pre-tenure academics. Studies in Higher Education,40(10), 1770–1785.

McAlpine, L., Jazvac-Martek, M., & Hopwood, N. (2009). Doctoral student experience in education: Activities and difficulties influencing identity development. International Journal for Researcher Development,1(1), 97–109.

McCormack, C. (2004). Storying stories: a narrative approach to in-depth interview conversations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology,7(3), 219–236.

McInnis, C. (2000). Changing academic work roles: The everyday realities challenging quality in teaching. Quality in Higher Education,6(2), 143–152.

National Union of Students. (2013). Postgraduates Who teach. Retrieved from https://www.nus.org.uk/PageFiles/12238/1654-NUS_PostgradTeachingSurvey_v3.pdf.

Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., & Terry, K. (2006). Possible selves and academic outcomes: How and when possible selves impel action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,91(1), 188.

Oyserman, D., & Fryberg, S. (2006). The possible selves of diverse adolescents: Content and function across gender, race and national origin. Possible selves: Theory, research, and applications,2(4), 17–39.

Pearson, M., & Brew, A. (2002). Research training and supervision development. Studies in Higher Education,27(2), 135–150.

Peterson, E. B. (2014). Re-signifying subjectivity? A narrative exploration of ‘non-traditional’ doctoral students’ lived experience of subject formation through two Australian cases. Studies in Higher Education,39(5), 823–834.

Pitt, R., & Mewburn, I. (2016). Academic superheroes? A critical analysis of academic job descriptions. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,38(1), 88–101.

Rond, M. D., & Miller, A. N. (2005). Publish or perish bane or boon of academic life? Journal of Management Inquiry,14(4), 321–329.

Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Sfard, A., & Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities: In search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educational Researcher,34(4), 14–22.

Sinclair, J., Barnacle, R., & Cuthbert, D. (2013). How the doctorate contributes to the formation of active researchers: What the research tells us. Studies in Higher Education,39(10), 1972–1986.

Sweitzer, V. B. (2009). Towards a theory of doctoral student professional identity development: A developmental networks approach. The Journal of Higher Education,80(1), 1–33.

Thiry, H., Laursen, S. L., & Loshbaugh, H. G. (2015). “How do i get from here to there?” An examination of Ph. D. science students’ career preparation and decision making. International Journal of Doctoral Studies,10(1), 237–256.

Turner, G., & McAlpine, L. (2011). Doctoral experience as researcher preparation: Activities, passion, status. International Journal for Researcher Development,2(1), 46–60.

Vitae. (2010). Vitae Researcher Development Statement (RDS), Careers Research and Advisory Centre (CRAC) Limited.

Walker, G. E., Golde, C. M., Jones, L., Bueschel, A. C., & Hutchings, P. (2009). The formation of scholars: Rethinking doctoral education for the twenty-first century. New York: Wiley.

Willison, J., & O’Regan, K. (2013). Researcher skill development framework. Retrieved from https://www.adelaide.edu.au/rsd/.

Winchester-Seeto, T., Homewood, J., Thogersen, J., Jacenyik-Trawoger, C., Manathunga, C., Reid, A., et al. (2014). Doctoral supervision in a cross-cultural context: Issues affecting supervisors and candidates. Higher Education Research and Development,33(3), 610–626.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Macquarie University Research Excellence Scholarship. My supervisors Dr Agnes Bosanquet, Prof Robyn Dowling and Dr Theresa Winchester-Seeto deserve special thanks. Agnes, in particular, provided generous feedback on the earlier drafts. I am also grateful to my research participants and the anonymous reviewers who provided valuable comments in the writing process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mantai, L. “Feeling more academic now”: Doctoral stories of becoming an academic. Aust. Educ. Res. 46, 137–153 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0283-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0283-x