Abstracts

Schools and school education systems within nations are vying to increase international student enrolments in secondary schools. This analysis of the change over a decade in the enrolment of international secondary students in Victoria, Australia, indicates how the processes of internationalisation and commercialisation of education have affected both public and private school sectors. Four factors have impacted on international senior student enrolments over a decade: global economic fluctuations; the growth of international schools globally targeting home country students; the emergence of overseas campuses for elite private schools and policies encouraging internationalisation. We propose that these forces, among others, are working in concert to reshape the nature of international student populations and international schooling in both home and host countries. These factors, together with an overarching instrumentalist policy approach underpinning the engagement of Australian schools with the international education market, provide new opportunities for less socio-economically advantaged schools to enter the international education market. It argues that the common idea of international students attending only elite schools no longer captures the phenomenon and raises questions as to how we understand what it means to be an ‘international’ school or student.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Transnational education, when ‘formal education takes place outside of local or national education systems, whether that is delivered ‘at home’ or overseas’ (Waters and Brooks 2011, p. 159), is a ‘new social phenomenon’ (Resnik 2012, p. 292). It arises in the context of the processes of globalisation in the form of increasing flows of people (international students, academics, teachers, policymakers), goods (curriculum, texts, technologies), ideas (policies, research) and money (fees, licences) (Appadurai 2004). The number of international fee-paying secondary students is predicted to double in the next decade, from 4.5 to 8 million, with the greatest increase being those from the rapidly growing middle classes in Asia (Farrugia 2014). China, India and Korea take up 53% of international students being educated in OECD countries, particularly US, UK, Germany and now Australia (OECD 2013; UNESCO-UIS 2011). Host country schools, while catering primarily for domestic students, now enrol international fee-paying students who seek to study a Western curriculum with the specific purpose of earning a national credential in the host country (Farrugia 2014; Parker 2011; Resnik 2012; Tate 2013). One motivation for both the individual student and the host country is that enrolment in a Western school pipelines into higher or vocational education institutions and thus increases a student’s capacity to gain employability skills and potentially employment in the global labour market, if not permanent residence in the host country (Leung et al. 2013; Farrugia 2014; Brown et al. 2008) and the host country employers have the capacity to recruit ‘enculturated’ international students (Blackmore et al. 2015). While the flow of international students into higher education is well researched, as yet there is less research to indicate the extent of transitioning between education sectors and into employment.

As a consequence, an intensely competitive global market in transnational school education has developed, with different school sectors and nations vying to increase their market share—as a source of additional revenue, to internationalise their curriculum and school appropriate for a globalised society, as well as to create a pathway for international secondary school graduates into their tertiary education sector (Farrugia 2014; Koh and Kenway 2012; Resnik 2012). This phenomenon of international secondary student mobility and the factors that shape where they go and why has been less the focus of either policy or research compared to the extent, nature and effects of them in university or vocational education sectors. Understanding the scope and scale as well as the patterns of secondary student mobility within the transnational education market provides a background to further research on the processes of internationalisation generally but also the aspirations, experiences and outcomes for international students specifically (Farrugia 2014; Resnik 2012).

To date, research on international secondary students has identified that attendance at a host country school enhances the possibility to acquire the language skills and international credentials that provide ‘positional advantage’ in the intense competition to enter the best local or overseas universities (Brown and Hesketh 2004; Choi 2004; Waters 2015). The OECD report (2013, p. 1) states:

Among the benefits perceived by an increasing number of students are the cultural enrichment and improved language skills, high-status qualifications, and a competitive edge to access better jobs. Studying abroad helps students to expand their knowledge of other societies, languages, cultures and business methods, and to leverage their labour market prospects (OECD 2004). Moreover, declines in the costs of international travel and communications also make it easier for students to study abroad.

Gaining the linguistic, educational and social capital over time also maximises employment options in a global economic markets after university graduation (Park and Bae 2009; Arber and Rahimi 2015; Gribble et al. 2017). While the international secondary student literature focuses on transnational educational mobility, it emphasises individual and familial agency over local and global forces (David et al. 2010). In contrast, our analysis discusses contextual factors that are simultaneously reshaping international school education for individuals and families both locally and globally and the nature of national education systems, factors such as fluctuating economic conditions, historical patterns of local provision and policy regimes (e.g. migration). We also take into account transnational schooling as the provocation for the growth of international schooling within countries which in turn impacts on the number of secondary students travelling overseas.

The first section of the paper argues, by analysing a longitudinal time-series analysis (2004–2013) of international student enrolment, that there is a positive relationship between international secondary student enrolments and the concurrence of particular economic conditions such as the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), changes in currency exchange rate and the cost of a public versus private school education. In response to Farrugia’s (2014) suggestion for the need for more localised state-level analyses of the economy/school relationship, we focus on Victoria, Australia. Victoria as a major Anglophile provider of transnational education, has the largest number of international students enrolled in secondary schools in Australia (see Table 1) and, with other Australian states, is the world’s largest provider of secondary schooling to the growing numbers of students from Asia after the United States of America (US). In the second section, we examine the impact of these factors on the international student ‘market share’ of Victorian public and private school sectors and the socio-economic profile of provider schools. As outlined in the third section, other factors play an equally important role in shaping transnational secondary student mobility including the global increase in the transnational delivery of Western high school certification programs for students, the establishment of overseas campuses by elite schools, and the proliferation of domestic schools in the source countries catering for local and international students by offering an international curriculum (e.g. International Baccalaureate) (Doherty et al. 2012). Finally, we refer to the recent development of Australian state and national policies in international education to address how this phenomenon is transforming all education sectors (Productivity Commission 2015). Together these developments are radically reshaping the character and possibilities of international secondary schooling through the processes of internationalisation in terms of curriculum, global outlook and domestic as well as international student mobility.

Conceptual framework and methodology

This analysis is framed by the interlinked phenomena of economic globalisation and the expansion of international schooling in the context of education becoming a multinational industry (Au and Ferrare 2015; Ball 2012). Economic globalisation is a multidimensional process; on the one hand, de-spatialising by breaking down borders; and, on the other hand, consolidating networks as well as forming new links (Tetzlaff 1998). The processes of globalisation, depicted as the transnational movement of capital, goods, knowledge and people (Appadurai 2004; Thrift 2005) are unifying in that they create and feed global labour markets in particular fields such as education, and differentiating as different markets produce new forms of distinction through rankings of schools and countries (elite versus local public) (Koh and Kenway 2012).

Stier (2004) offers a typology for the internationalisation of higher education from a Western perspective, identifying three main ideologies evident in discourses about international education: idealism, educationalism and instrumentalism. Higher education systems and institutions with an idealist ideology (for example, Swedish systems) put the focus of their internationalisation policies on the moral world by taking strategies that seek to enhance global knowledge, facilitate insights and stimulate empathy and compassion. Those with an educationalist ideology (for example, German higher education institutions) implement internationalisation programs while focusing on the individual’s learning processes via stimulating self-awareness and self-reflection, as well as training in intercultural competence (Stier 2004). The third ideology is that of instrumentalism. Australian, Canadian and the US universities/sectors, Stier argues, are typed as being driven by economic imperatives and putting the global market at the focal point of their internationalising policies: ‘Wealthy nations attempt to attract academic staff and fee-paying students from the ‘poor’ world, not only for short-term financial gains, but with an intent to keep their competence in the country, thus risking to ‘brain drain’ their home countries’ (Stier 2004, p. 91). Arguably this scenario has shifted over the past decades, but certainly the three ideologies are embedded in the discourses and policies about international schooling.

These conflicting ideologies are indicative of the array of motivations underpinning international student enrolments in Victorian schools and their offshore campuses. Recent policies and statements by federal and state governments illustrate how education is considered to be an international business to be encouraged and expanded, indicating the instrumentalist ideology as a primary driver in the Australian school sector’s competitiveness within the global education market. Stier (2004) argues that internationalisation strategies must be driven by more balanced ideologies instead of economic incentives only, and that internationalisation of higher education must be a means of reducing global disparity and exploitation. For effective strategies, there is also a need for closer cooperation between all stakeholders including policymakers, educational administrators, teaching staff and domestic and international students (Stier 2004; Stier and Börjesson 2010). A similar case, we argue, could be made for Australian secondary schools.

Our analysis draws on extant data as to the scope and scale of international secondary student mobility, with particular reference to Victoria, Australia. Because no single dataset provides a comprehensive picture of international secondary student enrolments in Australia, the statistics presented in Part 1 were extracted from multiple datasets:- (i) ‘International Student Commencements’ from the International Student Data compiled by Australian Education International (AEI) (AEI 2013); (ii) annual data on ‘Domestic Student Enrolments’ collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS); (iii) extraction of international secondary students from the annual award of 571 visas (full fee-paying, international student) from the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) and iv) statistics on the ‘Enrolment of International Students in the Victorian Certificate of Education’ (VCE)Footnote 1 provided by the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (VCAA). Additional data about the types of schools enrolling international students were extracted from the websites of the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) and the Independent Schools Association, Victoria. Information about changes in the value of the Australian dollar against the US dollar was sourced from Bloomberg and Westpac Economics.

Analyses involved combining these data and manual data matching using Excel and SPSS to cross-link the data and identify relevant relationships. Raw data on national commencements (sourced from the AEI datasets) were re-tabulated and calculated to explicitly show the proportion of international students at junior and senior secondary levels by State and Territory. Data on national enrolments were manually extracted from the ABS datasets, sorted and tabulated with the data manually extracted from the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (VCAA) datasets (see Table 2; Fig. 4). National data on international student commencement and the VCE enrolment data by school sector were separately time-matched with the currency rate trend data. A retrospective, time-series analysis of trend data on international students’ commencements, visas and enrolments at senior secondary level was conducted, in combination with institutional profile data on the enrolling secondary schools in Victoria, to identify changes over time and the impact of key factors on changes in the targeted population. Time-series data are seen as an important source of information to explore the changes over time and the impact of some key factors on the changes in a targeted population (Batini 2006; Christen 2012; Lee and Lee 2006).

In the second section, the data provided by the VCAA were combined with the geographic and socio-economic records from school profiles data that were manually sourced from the ACARA online data and converted to an SPSS data file format to create scatter plots for analysis. Information for the next section was extracted from the VCAA website, school/college websites and the related research literature. As is an issue with using extant data, there were limits that hindered us to develop a robust forecasting statistical model on the future growth pattern of international secondary education in Victoria and Australia. These limits were related to the shortage of detailed data, variations in the structure of the datasets and different time-lengths of consistent records of the data in the used datasets.

The analysis is completed by a critical policy analysis—one that asks what is the problem here, why now and with what effect—of the global and local policies informed by and informing the flows of secondary students. Rizvi and Lingard (2010) appraise various aspects of educational policy analysis and suggest ‘beyond critique, another purpose of critical education policy analysis is to suggest how policy could be otherwise—to offer an alternative social imaginary of globalisation and its implications for education’ (p. 70). Our critical policy analysis unpacks how the globalisation discourse on educational policy impacts on particular fields of educational activity, in this case international secondary schooling, as we examine the engagement of various individual and institutional social agents in the field of education within the context of global shifts in national economies and how it relates to international secondary student flows.

The economics of international secondary schooling

With many aspects of society affected by changes brought about by economic, political and cultural transformations resulting from the phenomenon of economic globalisation, schools have faced major challenges to develop strategies in order to cope with significant changes in provision, expectations and demographic shifts in a changing socio-economic context. Education is now linked tightly to the national economy in most countries, promising to be a source of economic growth and individual social mobility. The dominant discourse globally in both schools and universities driving reforms is for graduates to be twenty-first learners able to demonstrate a range of employability skills and capabilities such as communication, intercultural sensitivity, English language competence, critical thinking, problem solving, teamwork as well as being reflective and self-managing (Lees 2002). A longitudinal view of the relationship between economics and student enrolments both at national and at the state levels sheds light to some aspects of the way school sectors have positioned themselves in the international education market.

Australia has become a major Anglophile provider of schooling to international students from around the world but particularly from Asia, largely from China, India and Korea, with 3 out of 4 of such students enrolled in an OECD country (OECD 2013). From 2004 to 2013, a total of 102,201 fee-paying international students commenced school in Australia. Eighty-one percent of commencements were at the senior secondary level (83,127 students) compared to nineteen per-cent at the junior secondary level (19,074 students) (see Table 1).

The enrolment pattern of Victoria is strikingly different from other States or Territories. Nationally, Victoria has the largest proportion of senior (Years 11–12) secondary international student commencements (29.9%), despite having only 25% of the total national commencements and one of the lowest percentages of junior (Years 7–10) secondary international student commencements (1.9%). At the state level, the figures in Table 1 show that 98% of international 571 visas commencements were for senior secondary school compared with only 2% for junior secondary.

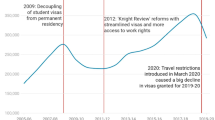

While there is significant evidence that economic and policy changes (e.g. visas, migration) impact on enrolments of international students in tertiary education in Australia (Connelly and Olsen 2012, 2013; Gribble et al. 2015), a similar impact is indicated in a comparison of national, annual changes in the number of international student visas issued for senior secondary students aged 15–19 years (under 571 visas) when considered against the timing of the GFC and changes in the value of the Australian dollar against the US dollar (see Fig. 1).

At the national level, there is an inverse relationship between the numbers of visas granted, the commencement of full fee-paying students and the currency rate. In short, student numbers decline when the Australian dollar is strong and increase when the value of the dollar drops against the US dollar. The number of 571 visas granted dropped significantly after the GFC in 2007–2008. Enrolment numbers continued to decrease at a slower pace from 2009 to 2012 against a rising Australian dollar but have partially recovered since 2012 alongside a declining Australian dollar.

National patterns may not be replicated at the state/territory level or in the final years of schooling. In Victoria, students must complete senior secondary (Years 11 and 12) and the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) to graduate and immediately access higher education if they achieve a requisite ATAR (aggregate adjusted score of a specified number of subjects) for their selected course at their chosen university. As Fig. 2 shows, the number of international students enrolled in senior secondary has declined steadily since the GFC. Further, while more than a third of schools in Victoria enrolled at least one international senior secondary student between 2004 and 2015, the overall number of schools admitting international students declined between 2005 and 13 from 237 to 214, a decline continuing since the GFC (see Fig. 2).

The overall decline in international students as a proportion of all senior secondary enrolments from 4.7% in 2004 to 2.6% in 2013 (see Table 2) reflects both the overall drop in international student enrolments and an increase in the number of domestic students staying at school to obtain their VCE, continuing the decade long trend.

With the development of the global economy, a range of new strategies have been taken by public and private providers in the higher education, vocational education and schools to maintain recruitment. The decline in both the number of international students and schools has been accompanied by a significant shift in the market share between the public (government) and private (independent and Catholic) schools enrolling international students in the senior secondary years.

As Fig. 3 shows, since 2004 international VCE enrolments have increased by 19.6% in government schools and decreased by 19.6% in independent schools while Catholic school enrolments have remained constant. These changes coincided with, and have accelerated since the GFC (2007–2008), indicating that government schools are preferred when cost is an issue. As a result, with 55.7% of all enrolments, the government school sector continues to be the largest provider of senior secondary schooling for international students in Victoria.

Figure 4 shows that the shift in international students from the private to the public sector has also meant that government schools have increased their proportion of international VCE enrolments overall despite negative growth from 131 to 120 in the number of enrolling government schools, the reduction from 31 to 15 of Catholic schools despite a 1.5% increase in enrolments, while the number of independent schools has remained relatively stable from 75 to 79 across the decade despite a 19.6% decrease in enrolments. Differences in cost in each sector offer one explanation. In Victoria, all international students pay tuition fees regardless of school sector. But tuition fees differ significantly between government, independent and Catholic schools, with government schools being the least expensive charging a fixed annual tuition fee for senior secondary school students of AUD 15,088 regardless of location, dropping to AUD 13,612 for a second or subsequent sibling (DET-VIC 2015b). Non-government schools charge higher tuition fees for international students because while all private schools receive some level of government subsidy for domestic students depending on their postcode from the Australian government, the majority of costs is funded through tuition fees (Independent Schools Victoria 2015). This varies considerably between the Catholic systemic sector enrolling about 20% of all students in Australia and the non-Government secular and faith-based providers varying from the elite high-fee schools to small low-fee fundamentalist Christian, Jewish, Muslim and community schools (Independent Schools Victoria 2015). A random sample of independent school websites show that the average tuition fees for an international student range from AUD 33,000 to 47,000 per annum, as in some instances it includes boarding. In contrast, the average annual tuition fees for a domestic student in his/her final year of senior secondary at one of the high-fee non-government school in 2013 was around AUD 24,081, although most still receive government funding (Hadfield 2013). While tuition fees at Catholic schools are higher than at government schools, they are significantly lower than the government-funded independent schools and vary widely depending on the amount of support from the diocese or religious order sponsoring the school.

Tuition fees are only part of the cost to families of sending a child to school in another country. Modelling by the Victorian Department of Education estimates that the living expenses for an international student range from AUD 17,000 to 25,000 per annum. This includes accommodation and meals,Footnote 2 books, uniforms, exam fees, transport, telephone and personal expenses and health insurance (DET-VIC 2015a, b, c). Homestay, whereby a domestic family plays host to an international student for remuneration, is ‘the most common form of accommodation for international school students enrolled with providers without access to on-campus boarding facilities’ AEI (2008). While tuition and living costs can vary significantly between different categories of schools, an average cost for government schools is AUD 15,808 plus AUD 21,000 living expenses totalling AUD 36,808 per annum compared to the high costs of independent schools with average costs of AUD 33,000 tuition and AUD 21,000 living expenses, totally AUD 55,000 per annum.

Figure 5 shows government schools gained market share of VCE enrolments between 2007 and 2010 despite the GFC and a rising Australian dollar, although numbers dropped slightly in subsequent years even against a fall in the Australian dollar. In contrast, enrolments in independent schools declined significantly prior to the GFC despite a favourable exchange rate, a decline accelerated post-GFC, whereas currency fluctuations or the GFC had negligible impact on Catholic school enrolments.

Changes in enrolments compared with currency fluctuations and the GFC. Data VCAA (2013), Bloomberg reported by Westpac Economics (2015)

The declining number of international secondary school students in Victoria relative to the national total may reflect the disaggregated nature of the statistics (e.g. short-term programs are more evident in other states) or may reflect the increased attraction of Australia’s Anglophile competitors, specifically the United States of America, Canada and the United Kingdom (UK), where the cost of secondary schooling is more affordable and also offers a direct route to more highly ranked international universities (Farrugia 2014).

Even at lower rates of Australian dollar in 2015/2016, tuition fees for international secondary students at public schools in the US and Canada are lower than in Victoria. Tuition at a US public school, for example, typically ranges from USD 3000–10,000 (Farrugia 2014, pp. 18–19), compared to AUD 15,808 (USD 11,600)Footnote 3 although attending a non-religious, private school in the US is around USD 30,000 in average which is almost equal to the tuition costs of elite independent schools in Victoria which range from AUD 33,000 to 47,000 (USD 24,090–34,310) per annum. In Canada, tuition for international students is correspondingly lower than in Victoria (Australia), ranging from CAD 8000–14,000 (USD 6400–11,200) at public secondary schools and CAD 12,000–18,000 (USD 9600–14,400) at private schools (Schools-in-Canada 2016). Tuition fees at a UK public school ranging from £8000 to 16,000 (USD 12,000–24,000), and at a UK independent school averaged £36,000 (USD 54,000) (British Council 2016) are higher than any of Victoria, Canada and the US.

Proximity to Asia is also a factor favouring Australia, although increasingly less so with improved online communication, as well as a families’ ability to meet the travel, tuition and living costs of schooling a child in another country.

Transnational schooling and the internationalisation of curriculum

Another factor influencing the numbers of secondary students travelling overseas is the parallel growth of international schools and domestic schools in both source and provider countries offering an ‘international’ curriculum and certification. This is illustrated by the rapid growth of International and domestic schools in both source (China, UAE, India, Singapore) and provider (USA, UK and Australia) countries offering the International Baccalaureate (IB), a program originally developed for the children of diplomats, government officials or corporate executives working overseas (Doherty et al. 2012). The IB in particular is a form of distinction in the Australian domestic market and attracts international students to the West (ISC 2015). Asia’s growing middle class is the driver of the demand for a foreign curriculum and English-medium instruction (ICEF Monitor 2014) in Asian source countries (China, UAE, India & Singapore) and Southern Asia (Brummitt and Keeling 2013; Bunnell 2014; Pearce 2013). China has seen the increase from 22 international schools enrolling 7268 children in 2000 to 260 international schools enrolling 119,319 students in 2010 and then to 342 international schools enrolling 186,773 students across 54 cities in 2013 (iS 2013). In 2013, almost half of the international schools world-wide are English-medium schools and use curricula from England (2924 schools) or the United States (1684 schools) and are taught by expats (Arber et al. 2015).

There is a parallel trend, with local schools in source countries for Western recruitment such as China and India using English as the medium of instruction and offering overseas developed programs in English leading to an internationally recognised global high school credential. E.g. International Baccalaureate Diploma Program (IB) (17%), Cambridge programs leading to the International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSEs) (25%), American SAT (PSAT) (16%) and the International A Level (GCE A) (14%) (Clark 2014). This is part of a wider trend of transnational provision and delivery of Western schooling world-wide. Strategies include the establishment of overseas campuses by elite schools such as the Victorian private school, Haileybury College, which has a campus in Tianjin through a joint venture partnership with Beijing Capital LandFootnote 4 (Grigg 2015). Another is the expanding practice of licensing by destination countries such as the UK, USA, Canada, Australia of curriculum and assessment programs to schools and colleges overseas. The Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority has licensed the Victorian Certificate of Education in twenty-two countries, including South Africa, Timor Leste, Vanuatu, United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia (VCAA 2015). Since 2002 more than 3000 Chinese students have successfully completed the VCE in 15 schools located in different Chinese cities. It is estimated that in China, for example, around 3,000 domestic schools offer such programmes (iS 2013). This parallel growth in international and domestic schools offering an international curriculum to local students is ‘a localisation, even a popularisation, of International Education in the developing world’ (Pearce 2013, p. 16). This transnational expansion of Australian schooling is important in creating and consolidating the international market as most often recruitment works through word of mouth.

Access to international schools at home with the promise of an ‘international’ curriculum (the IB being a liberal arts curriculum that is student centred, about independent learning and civic responsibility) produces intercultural competency. English language proficiency is a significant factor influencing parental decisions to send their child overseas for secondary schooling and it is a key aspect of access to and success in higher education in the West and also graduate employability (Arber and Rahimi 2015; Gribble et al. 2015). The internationalisation of schooling together with economic factors therefore works to reshape mobility patterns and contributes to the phenomena of the ‘immobile international student’ (Arber et al. 2015). Although the costs of per student per year in international schools in the home country are expensive compared to government schools, this is less significantly less costly than sending a child to study in Australia, with the added benefit of enabling students to retain close connections to their family, friends, society and culture.

Changing patterns in school enrolments of international students

Australian government policy, in order to be attractive to international students, claims to have both world class universities and quality of higher education across the sector (Australian Government 2016). Likewise, school quality and student achievement are ‘crucial to the long term sustainability of the international school sector’ (AEI 2008, p. 11) and both are closely aligned with the socio-economic status (SES) of families in each school (Perry and McConney 2010). ICSEA is a scale that details the socio-economic status of each Australian school to enable numerical comparisons of the average level of educational advantage of the school’s student population and is used by education systems as a proxy for SES. The national agency, ACARA, calculates the ICSEA score for each school in Australia using variables that include family background information on each student, such as parental education and occupation, the proportion of Indigenous students and students with a language background other than English, and the school’s metropolitan, regional or remote geographical location (ACARA 2012, 2013a, b). An ICSEA score above 1000 indicates greater socio-economic and educational advantage; an ICSEA score below 1000 indicates greater disadvantage. This information—ICSEA and student achievement in terms of VCE, VCAL and training as well as post-school outcomes—is placed on MySchool website and readily available to parents. Studies have indicated that parents of international students are higher users of this website to glean information about a school while domestic parents tend to draw on local and familial networks as well as personal experience (Windle 2015). We examined the relationship between international, senior, secondary enrolments and the Index Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) of schools in each sector. SPSS-generated scatter plot charts were used to compare the enrolments per school and identify clusters and trends in the schools with various ISCEA scores in the three sectors at three time points, namely 2004, 2008 and 2013 (see Fig. 6a–c). The first and last time points are the beginning and end, respectively, of the decade under examination; 2008 is included because it coincides with the GFC.

Figure 6a–c show that there has been a consistent and constant decline in the number of international senior secondary enrolments in high ICSEA value schools, that is among the ‘elite’, high-cost independent schools and a rise in provision in the middle level ICSEA schools, the majority with the lowest ICSEA scores being government schools. High-cost private schools have become under these global conditions less competitive in the international student market either because of school policies as they already attract sufficient domestic fee-paying students, the inability to recruit students given their high fees within altered macro-economic conditions, and/or increased competition from the less costly, public school sector.

Australian policy shifts affecting international schooling

Finally, there is the changing and sometime volatile policy context. A Productivity Commission report (2015) on international education argued the case for an integrated policy approach because of the often perverse policy outcomes for the international education sector.

Over time, visa policy settings have been reviewed and adjusted frequently—perhaps too frequently. The impulses for change have been as disparate as reactions to crises, the desire to smooth out the peaks and troughs in student numbers, and the intention to balance the sustainable growth of the sector against the risks to the integrity of the immigration system (and national security) associated with the intake of international students. The swings in visa policy settings are partly symptomatic of the use of one policy lever—student visa settings—to achieve multiple policy objectives (Productivity Commission 2015, p 9).

Whereas international student in higher education and universities has been the focus of policy, both state and federal governments have now begun to address the transnational school market as part of a raft of economically driven policies as de-industrialisation speeds up and the mineral boom declines. Stier’s conflicting ideologies of international education (instrumentalist, idealistic, educationalist) are evident in recent policies which have emerged in response to the trends outlined earlier. First, that of national testing as a measure of educational quality. In Australia, due to the increase in the scope and scale of the international student market in Australia, both in schools and higher education, and the considerable financial issues that have emerged with the deregulation and collapse of many private providers in the VET sector, there has been a need to address this both with regard to regulation and as a national as well as state strategy, given that education is the third largest national export earner. Maintaining quality is linked strongly to sustaining market position.

Also from an instrumentalist position is the federal government’s draft National Strategy for International Education (2016) that was linked to the National Innovation and Science Agenda, in which the Minister states:

International education is recognised as one of the five super growth sectors contributing to Australia’s transition from a resources-based to a modern services economy, international education offers an unprecedented opportunity for Australia to capitalise on increasing global demand for education services (2016, p. 5).

This policy is about improving market share by providing ‘high quality, innovative products and services to students’ by strengthening the fundamentals, making transformative partnerships and competing globally—a blatantly consumer driven commercialised and economistic approach to international education as a global business from which governments can also profit (See also Productivity Commission report 2015). Similarly, in 2015, the launch of Victoria’s policy ‘The Education State’ prioritised education and Victoria’s Future Industries International Education Discussion Paper. Both statements positioned international education as critical to Victoria’s economic growth and economic strategy, although modified by wider global citizen discourses.

International education has stood as Victoria’s largest services export industry for over a decade. In 2013–1014, the onshore component of international education generated $4.7 billion in services exports for the State. An estimated 30,000 Victorians are employed by the sector. The outputs of international education are not just skilled graduates. International education offers a platform to assist the Victorian economy and our society to tackle some of the world’s greatest global challenges (Victorian Government 2014, p. 1).

USA, UK and Canada were cited as the key competitors in the ‘education boom’. Now over 200 primary and secondary government schools accredited to enrol students with a 571 Visa, with a considerable additional number of students’ parents being higher education students or permanent residents.

Second, a more educationalist if not idealist perspective is also evident within the discourses about international schooling. The OECD (2015) is working towards a 2018 PISA inclusion of a Global Competency for an inclusive world. Federally, this interest in international education for schools was stimulated with Labor’s White Paper (2011)—The Asian Century. The Coalition government has shifted policy towards a revitalisation of the Colombo plan in 2014. The Australian Curriculum’s cross curriculum priority of Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia now acknowledges the importance of including studies of Asia (SOA) and that students require ‘foundational and in-depth knowledge, skills and understandings of the histories, geographies, societies, arts, literatures and languages of the diverse countries of Asia and their engagement with Australia’. The Asia Australia Education Foundation has funded research on Asia literacy (Halse et al. 2013) and how schools and professional development can be assisted. This initiative is largely premised upon educationalist approaches and notions of the millennial student as a global citizen.

Furthermore, with many Victorian schools having forged partnerships with schools overseas over the past decades with the aim to widen the educational horizons of students, the Victorian Department of Education has developed over that decade protocols regarding student wellbeing, guardianship and pastoral care as well as sister school relationships. By 2016, any school with international students has an International Student Coordinator and English language intensive support framed by regulations including a School Accreditation System, Quality Standards and Review Program run through the International Education Division, and in 2016 a newly developed online Guide to schools. The Victorian policy discourse is that leading twenty-first century schools have an international dimension in their curriculum and profile.

These policies directly focusing on international education are part of a policy assemblage that impacts on the field generally. Other policies include transnational agreements and migration policies. Australian higher education was significantly impacted when the rules of the game were changed in 2012 and the link between studying in Australia and permanent residence were severed (Blackmore et al. 2014; Gribble et al. 2017). A rapid downturn of student enrolments and significant pressure from Universities Australia, the body representing the 39 Australian universities, led to the introduction of new post-study work visas. Given that choice of destination country for higher education is often word-of-mouth, it could be expected that such policy shifts also impact on the secondary school sector, although the above analysis indicates that the current policy assemblage is more supportive than discouraging of school students.

Conclusion

This time-series analysis and the discussion of the internationalisation of secondary school provision and policy shed light on some aspects of Australia’s capacity to attract international secondary students and how this differs across school sectors within Victoria. It counters the broadly accepted assumption that international students are most likely concentrated in non-governmental school sectors. Government schools follow a broadly accepted educational and idealist ideology in terms of how they perceive of the benefits of international students in their schools in terms of cross cultural interaction with the domestic students. At the same time, the reality of their practices as well as Australian and Victorian policies tends to indicate that economic benefits are a major, but not the only, driver, particularly for many middle tier government schools which have due to their funding models premised upon numbers with additional equity funds based on ICSEA data have little discretionary funding to enrich their teaching program.

Furthermore, schools across all sectors are also positioned in a context where external forces of economic globalisation–financial crises, currency rates, and perceptions as to quality—influence choices about where parents send their children for schooling. However, the current policy assemblage that frames system and school’s possibilities with regard to fees, visas and accreditation positions government schools more favourably. We have argued that high fee, and therefore private and Catholic schools, have been in Victoria impacted on more than government schools by both currency fluctuations as indicated in the shift of international student enrolments from the schools with higher ICSEA to the schools with medium and lower ICSEA. Other factors influencing parents’ decisions include the changing economic conditions such as the GFC, the availability of local schools which offer an international (English) curriculum of equivalent status and the difficulty of obtaining visas. The expansion of enrolments, though not necessarily number of schools, is also a response to government schools being encouraged to be more entrepreneurial via engagement in international education in a synergic complex of polices promoting international education and empowering the competitiveness of the Australia in a global context. These findings negate the conventional wisdom that international students are the exclusive province of elite private schools and raise questions about the extent to which Australia’s international students belong to the wealthy, elite, transnational capitalist class of students identified in other countries (see Brooks and Waters 2014; Koh and Kenway 2012). Further research is required to investigate the background of those international students in these government schools to consider issues around secondary student mobility, gender, class and ethnicity.

Another explanation, we propose, is a significant growth in the local delivery of international high school certification in home countries, another dimension of the transnational school market, which enables families to procure an international high school certification without the financial, social and cultural losses involved in sending a child overseas to study. As we illustrate, local delivery of transnational schooling by international providers to immobile international students (that is, those remaining in their home country) can take different forms. It includes licensing curriculum and high school examinations to schools and education authorities overseas; the establishment of overseas campuses by elite schools; and expansion of international schools delivering a mix of local and overseas curriculum and assessment to, predominately, local students. Again, the Victorian government and independent school sector are very active in all these aspects. The growth in immobile students means that it is no longer sufficient to conceptualise international students as those who study outside of their home country. Nor is it adequate to view international schooling as operating within the geographic and cultural boundaries of a particular nation–state. Rather, international school education has become an increasingly transnational phenomenon. These findings point to the need for detailed research to identify the relative influence of these different factors in specific school education contexts and for close analysis of how schools, schooling systems and nation-states seeking to increase senior secondary enrolments will need to conceptualise this work in the future.

Notes

The VCE is the certificate for graduation awarded after completing senior secondary school (Years 11–12) and which enables admission to higher education provided a student achieves the ATAR score required for their selected course. Students register with VCAA to undertake the VCE at the beginning of Year 11.

Homestay, whereby a domestic family plays host to an international student for remuneration, is ‘the most common form of accommodation for international school students enrolled with providers without access to on-campus boarding facilities’ AEI (2008). The Strategic Framework for International Engagement by the Australian School Sector 2008–2011. In: Department of Education EaWR, Australian Education International (AEI), Canberra.

Currency rates for 2015/2016.

Beijing Capital Land Ltd. is an investment holding company in China.

References

AEI. (2008). The strategic framework for international engagement by the australian school sector 2008–2011. In: Department of Education EaWR, Australian Education International (AEI) (Ed.). Canberra: AEI.

AEI. (2013). International student data., Australian Education International Canberra: Australian Government.

Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition. In V. Rao & M. Walton (Eds.), Culture and public action (pp. 59–84). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Arber, R., Blackmore, J., & Vongalis-Macrow, A. (Eds.). (2015). Mobile teachers and curriculum in international schooling. Rotterdam: Sense.

Arber, R., & Rahimi, M. (2015). International graduates’ endeavours for work in Australia: The experience of international graduates of accounting transitioning into Australian labour market, Chapter 4. In A. Ata & A. Kostogriz (Eds.), International education: Cultural-linguistic experiences of international students in Australia. Australia, QLD: The Australian Academic Press.

Au, W., & Ferrare, J. J. (Eds.). (2015). Mapping corporate education reform: Power and policy networks in the neoliberal state. New York: Routledge.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2012). National report on schooling in Australia 2010. Sydney: ACARA.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2013a). About ICSEA. The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). Retrieved from www.acara.edu.au/verve/_resources/Fact_Sheet_-_About_ICSEA.pdf.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2013b). National Report on Schooling in Australia 2011. Sydney: ACARA.

Australian Government. (2016). National strategy for international education 2025, Canberra.

Ball, S. J. (2012). Politics and policy making in education: Explorations in sociology. London: Routledge.

Batini, C. (2006). Data quality: Concepts, methodologies and techniques. Berlin: Springer.

Blackmore, J., Gribble, C., Farrell, L., Rahimi, M., Arber, R., & Devlin, M. (2014). Australian international graduates and the transition to employment. Melbourne: Deakin University.

Blackmore, J., Gribble, C., & Rahimi, M. (2015). International education, the formation of capital and graduate employment: Chinese accounting graduates’ experiences of the Australian labour market. Critical Studies in Education, 1–20.

Bloom, D. E. (2004). Globalisation and Education: An Economic perspective. In M. M. Suarenz-Orozco & D. B. Qin-Hillard (Eds.), Globalisation, culture and education in the new millennium. London: University of California Press.

Bloomberg Reported by Westpac Economics. (2015). Financial year average exchange rates. Sydney: Westpac Banking Corporation.

British Council. (2016). Cost and fees for international students. Retrieved from http://www.educationuk.org/global/articles/costs-and-tuition-fees-for-international-students.

Brooks, R., & Waters, J. (2014). The hidden internationalism of elite English schools. Sociology, 43(6), 1085–1102.

Brown, P., & Hesketh, A. (2004). The mismanagement of talent: Employability and jobs in the knowledge economy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brown, P., Lauder, H., & Ashton, D. (2008). Education, globalisation and the future of the knowledge economy. European Educational Research Journal, 7(2), 131–156.

Brummitt, N., & Keeling, A. (2013). Charting the growth of international schools. In R. Pearce (Ed.), International education and schools: Moving beyond the first 40 years (pp. 25–36). London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Bunnell, T. (2014). The changing landscape of international schooling: Implications for theory and practice. New York: Routledge.

Choi, S. (2004). Education in the market place: Hong Kong’s international schools and their mode of operation. Comparative Education, 40(1), 137–138.

Christen, P. (2012). Data matching: Concepts and techniques for record linkage, entity resolution, and duplicate detection. Berlin: Springer.

Clark, N. (2014). The booming international schools sector. Retrieved from http://wenr.wes.org/2014/07/the-booming-international-schools-sector/.

Connelly, S. & Olsen, A. (2012). Education as an export for Australia: More valuable than gold, but for how long? Paper presented at The Australian International Education Conference, Melbourne. Retrieved from http://aiec.idp.com/topmenu/about/past-conferences/2012-2.

Connelly, S., & Olsen, A. (2013). Education as an export for Australia: Green shoots, first swallows, but not quite out of the woods yet. Paper presented at The Australian International Education Conference, Melbourne. Retrieved from http://aiec.idp.com/topmenu/about/past-conferences/2013-2.

David, S., Dolby, N., & Rizvi, F. (2010). Globalization and postnational possibilities in education for the future: Rethinking borders and boundaries. In Global pedagogies (pp. 35–46). Netherlands: Springer.

DET-VIC. (2015a). International student program: Applying to study in Victoria. In: Division DoEaTTIE. Melbourne: State Government of Victoria: DET.

DET-VIC. (2015b). International student tuition fees for Victorian government schools—2015. Retrieved from http://www.study.vic.gov.au/deecd/schools-in-victoria/apply/en/school-fees.cfm.

DET-VIC. (2015c). Right school right place: A Full guide to Victorian government schools enrolling international students 2015–16. Retrieved from http://www.study.vic.gov.au/deecd/schools-in-victoria/resources/en/publications.cfm.

DIBP. (2015). Schools sector visa (subclass 571). Retrieved from http://www.immi.gov.au/Visas/Pages/571.aspx.

Doherty, C., Luke, A., Shield, P., & Hincksman, C. (2012). Choosing your niche: The social ecology of the International Baccalaureate Diploma in Australia. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 22(4), 311–332.

Farrugia, C. (2014). Charting new pathways to higher education: International secondary students in the United States. New York: Center for Academic Mobility Research, Institute of International Education.

Gribble, C., Blackmore, J., & Rahimi, M. (2015). Challenges to providing work integrated learning to international business students at Australian universities. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 5(4), 401–416.

Gribble, C., Rahimi, M., & Blackmore, J. (2017). International students and post study employment: The impact of university and host community engagement on the employment outcomes of international students in Australia. In L. T. Tran & C. Gomes (Eds.), International student engagement and identity (Vol. 2, pp. 15–39). Dordrecht: Springer.

Grigg, A. (2015). China beckons as a rich market for Australian schools. Financial Review. Retrieved 29 March 2015 from http://www.afr.com/news/policy/education/china-beckons-as-a-rich-market-for-australian-schools-20150319-1m39px#ixzz3xpyFrx9P.

Hadfield, S. (2013). Demand for private school places sees fees triple. Herald Sun, Australia, May 19, 2013.

Halse, C., Cloonan, A., Dyer, J., Kostogriz, A., Toe, D., & Weinmann, M. (2013). Asia literacy and the Australian teaching workforce. Melbourne: Education Services Australia.

ICEF Monitor. (2014). New data on international schools suggests continued strong growth. Retrieved from http://monitor.icef.com/2014/03/new-data-on-international-schools-suggests-continued-strong-growth-2.

Independent Schools Victoria. (2015). School fees. Retrieved from http://www.is.vic.edu.au/independent/facts/school-fees.htm.

iS. (2013). Focus on China, International School. Suffolk: John Catt Educational Ltd.

ISC. (2015) International school consultancy group. Retrieved from http://www.isc-r.com/.

Koh, A., & Kenway, J. (2012). Cultivating national leaders in an elite school: Deploying the transnational in the national interest. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 22, 333–351.

Lee, Y. W., & Lee, Y. W. (2006). Journey to data quality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lees, D. (2002). Graduate employability—Literature review: LTSN Generic Centre. Retrieved from http://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/esecttools/esectpubs/leeslitreview.pdf.

Leung, L., Lee, M., Teng, Y., Li, J., & Gan, A. (2013). Where do they head for university studies? The university destinations of Chinese IBDP graduates: A study of the international baccalaureate diploma program in China. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Comparative Education Society of Hong Kong.

OECD. (2004). Internationalisation and trade in higher education: Opportunities and challenges. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013). How is international student mobility shaping up?, Education Indicators in Focus, 14, OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2015). Education at a glance 2015: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing.

Park, J., & Bae, S. (2009). Language Ideologies in educational migration: Korean Jogi Yuhak families in Singapore. Linguistics and Education, 20(4), 366–377.

Parker, W. C. (2011). ‘International education’ in US public schools. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9, 487–501.

Pearce, R. (Ed.). (2013). International education and schools: Moving beyond the first 40 years (1st ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Perry, L. B., & McConney, A. (2010). Does the SES of the school matter? An examination of socioeconomic status and student achievement using PISA 2003. Teachers College Record, 112(4), 1137–1162.

Productivity Commission. (2015). Annual report 2014-15: Annual report series, Canberra.

Resnik, J. (2012). Sociology of international education—an emerging field of research. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 22, 291–310.

Rizvi, F., & Lingard, B. (2010). Globalizing education policy. London & New York: Routledge.

Schools-in-Canada. (2016). Public international high schools: Featured high schools. Retrieved from http://www.schoolsincanada.com.

Stier, J. (2004). Taking a critical stance toward internationalization ideologies in higher education: Idealism, instrumentalism and educationalism. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 2(1), 1–28.

Stier, J., & Börjesson, M. (2010). The internationalised university as discourse: Institutional self-presentations, rhetoric and benchmarking in a global market. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 20(4), 335–353.

Tate, N. (2013). International education in a post-Enlightenment world. Educational Review, 65, 253–266.

Tetzlaff, R. (1998). World cultures under the pressure of globalization: Experiences and responses from the different continents. Retrieved from http://lbs.hh.schule.de/welcome.phtml?unten=/global/allgemein/tetzlaff-121.html.

Thrift, N. (2005). Knowing capitalism. London: SAGE Publication.

UNESCO-UIS. (2011). Global education digest: Comparing education statistics across the world 2011. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (VCAA). (2015). VCAA International. Retrieved from http://www.vcaa.vic.edu.au/international/Pages/Home.aspx.

Victorian Government. (2014). Connected to the world: A plan to internationalise Victorian schooling. East Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer.

Waters, J. (2015). Educational imperatives and the compulsion for credentials: Family migration and children’s education in East Asia. Children’s Geographies, 13(3), 280–293.

Waters, J., & Brooks, R. (2011). International/transnational spaces of education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9(2), 155–160.

Windle, J. A. (2015). Making sense of school choice: Politics, policies, and practice under conditions of cultural diversity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rahimi, M., Halse, C. & Blackmore, J. Transnational secondary schooling and im/mobile international students. Aust. Educ. Res. 44, 299–321 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0235-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0235-x