Abstract

Postoperative chylous ascites is a rare complication from operative trauma to the cisterna chyli or lymphatic vessels in the retroperitoneum. In the present study, we aimed to identify the incidence of postoperative chylous ascites in patients treated for ovarian cancer and to describe its management. We retrospectively reviewed all patients submitted to surgery for ovarian cancer at our Institution from October 2016 to November 2018. We analyzed the clinicopathological features, including the primary tumor histology, stage, grade, surgical procedure, median number of harvested pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes. We described our experience in the diagnosis and management of chylous ascites. Five hundred and forty-six patients were submitted to surgery for ovarian cancer and 298 patients received pelvic and/or para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Chylous ascites occurred in 8 patients with an incidence of 1.4% in the overall population and a 2.68% among patients receiving lymphadenectomy. All patients received total parenteral nutrition (TPN) with Olimel N4E 2000 mL (Baxter®) and somatostatin therapy with 0.2 mL per 3 times/day for a median of 9 days (range 7–11). Median hospital stay was 15 days (range 7–16). All patients were successfully managed conservatively and none required surgical correction. Conservative management of chylous ascites with TPN, somatostatin and paracentisis is feasible and effective. These data should be confirmed by prospective multicentric studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chylous ascites is a rare form of ascites resulting from an extravasation of milky chyle rich in triglycerides (usually > 110 mg/dL) into the peritoneal cavity, following obstruction or disruption of major lymphatic channels. It has been described in patients with congenital lymphatic anomalies, tuberculosis, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, and malignancies [1,2,3]. Moreover, it can occur after a surgical trauma of cisterna chyli or lymphatic vessels during abdominal surgery. Although it is still rare, there is evidence of an increase of incidence in patients receiving gynecologic cancer surgery, probably due to retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection [1].

The most common findings associated with this rare complication are abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting and milky-appearing discharge from the vagina after gynecologic surgery, if an intraperitoneal drain is not placed [1,2,3,4].

Management of postoperative chylous ascites may be challenging. In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed all patients who underwent surgery for ovarian cancer to identify the incidence of this rare complication in our series and to describe its management.

Materials and methods

In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed all patients who underwent surgery for ovarian cancer at our Institution from October 2016 to November 2018.

Study data were retrospectively extracted using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Policlinico Agostino Gemelli Foundation, IRCCS. This study protocol was approved by Internal Review Board (IRB).

Chylous ascites was defined as milky-white appearance or high triglyceride levels (> 110 mg/dL) in the fluid obtained from diagnostic paracentesis or less commonly from the peritoneal drainages. Women showing these characteristics were then selected for final analysis.

Clinico-pathological features, including the primary tumor histology, stage, grade, surgical procedure, type of lymphoadenectomy, median number of removed pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, and number of metastatic lymph nodes were collected and analyzed.

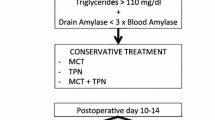

Conservative treatments included total parenteral nutrition, paracentesis and somatostatin followed by additional low-fat diet supplemented with medium-chain triglycerides as maintenance therapy for a minimum of 1 month. Complete clinical success was defined as the disappearance of the ascites and/or clinical symptoms, such as abdominal distension and dyspnea. Patients with progressive abdominal distension or with increasing or stable chylous drainage despite treatment after 30 days were classified as non-responsive.

The time to chylous ascites onset was defined as the interval between the surgical procedure and the appearance of chylous ascites. The time of resolution was defined as the time from initial diagnosis and the condition resolution (abdominal drainage tube of chylous ascites < 300 mL or ascites tending to be limpid fluid). White blood cell counts and body temperature measurements were performed to exclude infected ascites fluid (particularly bacterial peritonitis).

Results

Five hundred and forty-six patients were submitted to surgery for ovarian cancer in the study period. Among them, 298 women underwent pelvic and/or para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Chylous ascites occurred in eight patients, with an overall incidence of 1.4% in the entire population and a 2.68% in the subgroup of patients submitted to lymphadenectomy (Table 1): two for staging purposes and five during primary debulking surgery and 1 during interval debulking surgery.

All patients with chylous ascites had bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Clinicopathologic features of all patients are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The median number of lymph nodes was 11.5 (range 1–28) in the pelvis and 17 (range 6–40) in the para-aortic area. A variety of approaches (i.e., laparoscopy, robotic, and open surgery) and methods, (i.e., standard or advanced bipolar cautery) were used to dissect the lymphatic tissue (Fig. 1). Additionally, absorbable suture or hemoclips were used to ligate all vascular and lymphatic channels during dissection. No hemostatic or sealant agents such as fibrin glue were routinely used after retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND). Median time from surgery to the development of symptoms was 7 days (range 6–9). Six women (75%) developed chylous ascites after discharge from the hospital and were re-admitted through emergency room (ER) for occurrence of symptoms, such as abdominal distension, bloating, and dyspnea.

Ultrasonography and paracentesis were used for diagnosis. All women received a percutaneous drainage that remained in place for a median of 9 days (range 7–12). A maximum output of 1000 mL was allowed per day. In 4 women the fluid was examined biochemically, and 110 mg/dL was accepted as the threshold level for diagnosis of chylous ascites.

The management of this complication was chosen after a nutritional evaluation according to the attending physician. All patients received total parenteral nutrition (TPN) with Olimel N4E 2000 mL (Baxter®) and somatostatin therapy with 0.2 mL 3 times per day for a median of 9 days (range 7–11). Median time of recovery was 15 days (range 7–16).

Patients with complete clinical success took minimum 1 month of additional diet therapy as maintenance therapy with low-fat diet supplemented with medium-chain triglycerides. Only one patient needed to additional TPN after discharge. No patient required surgical correction since all of them responded to conservative treatment with the longest response requiring 22 days.

Discussion

The incidence of chylous ascites after surgery for gynecologic malignancies is not well established. Han et al. reported an incidence of 0.32% after para-aortic lymphadenectomy and 0.077% after pelvic lymphadenectomy, following staging surgery for gynecological malignancies [5]. In the same year, Tulunay et al. found a higher incidence up to 2% of chylous ascites with staging surgery for gynecological malignancies, probably due to a more aggressive lymphadenectomy in the para-aortic region [6]. Indeed, the incidence of chylous ascites in Tulunay’s study is similar to ones reported after retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for testicular cancer [7, 8].

Regarding ovarian cancer, recently Harter et al. published results of Lymphadenectomy in Ovarian Neoplasms (LION) trial where patients with advanced ovarian cancer and pre- and intra-operatively clinical negative lymph nodes were randomized intra-operatively to receive lymphadenectomy or not.

LION trial shows between the two arms no differences in term of overall survival and an increased surgical morbidity in the lymphadenectomy arm without mentioning the rate of chylous ascites. Other data regarding chylous ascites after lymphadenectomy for ovarian cancer are limited to case report/series showing a widespread heterogeneity.

Our analysis showed an incidence of 2.6% among patients submitted to lymphadenectomy confirming data previously reported in the Literature. In our series six patients (75%) developed chylous ascites after discharge showing that this condition usually has a late onset.

Considering the reduced indications for lymphadenectomy in OC, both for early stage (ESMO-ESGO Guidelines, April 2018), where it stands only to clarify the role of adjuvant chemotherapy, and for advanced stage, where it is accepted only for resection of bulky nodes (LION trial), a further significant decrease of this condition is likely to happen in the near future. Finally, the introduction of sentinel node evaluation even in early stage OC might ensure adequate staging, while reducing complication related to lymph node dissection (Selly protocol, NCT03563781).

Chylous ascites management remains controversial, due to the rarity of this condition. In the literature we found a widespread heterogeneity of clinical conducts. Conservative treatment includes low-fat diets that are supplemented with medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) as well as total parenteral nutrition, somatostatin therapy and paracentesis.

While serial paracentesis can provide resolution, it may lead to prolonged leakage and increase the risk of infection [9, 10]. Therefore, this procedure should be reserved for patients with severe abdominal discomfort and dyspnea due to massive chylous ascites. We did not perform serial paracentesis because we routinely used intraperitoneal drainages. Surgical intervention should be indicated only for patients who do not respond to conservative management. Most authors wait for 4–8 weeks before proceeding with surgical exploration [4]. Conservative treatment methods have been reported with variable success rates in different studies. In a study by Frey et al. 12 patients were treated with diet only. In this series, five of these patients needed recurrent paracentesis but did not require surgery [1]. In another study by Tulunay et al., 7 (29%) of 24 patients required surgical correction [6]. Conversely, Han et al. and Zhao et al. reported 100% success rates for the conservative treatment of postoperative chylous ascites [5, 11]. Our findings were consistent with Han et al. [5] and Zhao et al. [11], and all patients responded to conservative therapy within 2 weeks.

Otherwise, scientific scenario seems to turn its view toward new technologies for gynecologic pathologies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], and a maximal effort in minimal invasive procedures by laparoscopy or robotic [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] or such as sentinel node [36,37,38] evaluation which could be the right way to obtain staging information erasing complication linked to lymph node dissection.

Several authors described the possibility to predict surgical and oncological outcomes to perform aggressive surgical procedures without increasing surgical morbidity [14, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

Considering all these aspects, quality of life represents a fundamental goal to reach, even if different factors play a role [47,48,49,50].

In our center, we applied a protocol shared with nutritionists and this conservative management seems to be able to control this complication.

Nevertheless, the best scheme and the correct timing are already unclear. However, a prospective multicenter randomized study able to confirm the superiority of conservative management (and which conservative management), is unlikely to be performed due to the rarity and future reduction of this condition. Therefore, this retrospective study, despite its evident biases, confirms that conservative management of chylous ascites is feasible and effective.

References

Frey MK, Ward NM, Caputo TA et al (2012) Lymphatic ascites following pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy procedures for gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol 125:48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.012

Shibuya Y, Asano K, Hayasaka A et al (2013) A novel therapeutic strategy for chylous ascites after gynecological cancer surgery: a continuous low-pressure drainage system. Arch Gynecol Obstet 287:1005–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2666-y

Steinemann DC, Dindo D, Clavien P-A, Nocito A (2011) Atraumatic chylous ascites: systematic review on symptoms and causes. J Am Coll Surg 212(899–905):e1–e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.010

Leibovitch I, Mor Y, Golomb J, Ramon J (2002) The diagnosis and management of postoperative chylous ascites. J Urol 167:449–457

Han D, Wu X, Li J, Ke G (2012) Postoperative chylous ascites in patients with gynecologic malignancies. Int J Gynecol Cancer 22:186–190. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e318233f24b

Tulunay G, Ureyen I, Turan T et al (2012) Chylous ascites: analysis of 24 patients. Gynecol Oncol 127:191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.023

Combe J, Buniet JM, Douge C et al (1992) Chylothorax and chylous ascites following surgery of an inflammatory aortic aneurysm. Case report with review of the literature. J Mal Vasc 17:151–156

Baniel J, Foster RS, Rowland RG et al (1995) Complications of post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. J Urol 153:976–980

Baniel J, Foster RS, Rowland RG et al (1993) Management of chylous ascites after retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer. J Urol 150:1422–1424

DeHart MM, Lauerman WC, Conely AH et al (1994) Management of retroperitoneal chylous leakage. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 19:716–718

Zhao Y, Hu W, Hou X, Zhou Q (2014) Chylous ascites after laparoscopic lymph node dissection in gynecologic malignancies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 21:90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2013.07.005

Gueli Alletti S, Vizzielli G, Lafuenti L et al (2018) Single-Institution propensity-matched study to evaluate the psychological effect of minimally invasive interval debulking surgery versus standard laparotomic treatment: from body to mind and back. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 25:816–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2017.12.007

Petrillo M, De Iaco P, Cianci S et al (2016) Long-term survival for platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer patients treated with secondary cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Ann Surg Oncol 23:1660–1665. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-5050-x

Plotti F, Scaletta G, Terranova C et al (2018) The role of novel biomarker HE4 in gynecologic malignancies. Minerva Ginecol. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0026-4784.18.04328-9

Valenti G, Vitale SG, Tropea A et al (2017) Tumor markers of uterine cervical cancer: a new scenario to guide surgical practice? Updates Surg 69:441–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-017-0491-3

Angioli R, Capriglione S, Aloisi A et al (2015) A predictive score for secondary cytoreductive surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer (SeC-Score): a single-centre, controlled study for preoperative patient selection. Ann Surg Oncol 22:4217–4223. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4534-z

Vitale SG, Capriglione S, Zito G et al (2019) Management of endometrial, ovarian and cervical cancer in the elderly: current approach to a challenging condition. Arch Gynecol Obstet 299:299–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-018-5006-z

Plotti F, Scaletta G, Aloisi A et al (2015) Quality of life in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: chemotherapy versus surgery plus chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 22:2387–2394. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4263-8

Plotti F, Montera R, Aloisi A et al (2016) Total rectosigmoidectomy versus partial rectal resection in primary debulking surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 42:383–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2015.12.001

Vitale SG, Valenti G, Gulino FA et al (2016) Surgical treatment of high stage endometrial cancer: current perspectives. Updates Surg 68:149–154

Rossetti D, Vitale SG, Gulino FA et al (2016) Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery for the assessment of peritoneal carcinomatosis resectability in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 37:671–673. https://doi.org/10.12892/ejgo3234.2016

Fagotti A, Costantini B, Gallotta V et al (2015) Minimally invasive secondary cytoreduction plus HIPEC versus open surgery plus HIPEC in isolated relapse from ovarian cancer: a retrospective cohort study on perioperative outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 22:428–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2014.11.008

Cianci S, Ronsini C, Vizzielli G et al (2018) Cytoreductive surgery followed by HIPEC repetition for secondary ovarian cancer recurrence. Updates Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-018-0600-y

Cianci S, Abatini C, Fagotti A et al (2018) Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for peritoneal malignancies using new hybrid CO2 system: preliminary experience in referral center. Updates Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-018-0578-5

Bellia A, Vitale SG, Laganà AS et al (2016) Feasibility and surgical outcomes of conventional and robot-assisted laparoscopy for early-stage ovarian cancer: a retrospective, multicenter analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294:615–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4087-9

Gueli Alletti S, Perrone E, Cianci S et al (2018) 3 mm Senhance robotic hysterectomy: a step towards future perspectives. J Robot Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-018-0778-5

Gallotta V, Conte C, Giudice MT et al (2017) Secondary laparoscopic cytoreduction in recurrent ovarian cancer: a large, single-Institution experience. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 25(4):644–650

Rossitto C, Cianci S, Gueli Alletti S et al (2017) Laparoscopic, minilaparoscopic, single-port and percutaneous hysterectomy: comparison of perioperative outcomes of minimally invasive approaches in gynecologic surgery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 216:125–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.07.026

Lagana AS, Vitale SG, De Dominici R et al (2016) Fertility outcome after laparoscopic salpingostomy or salpingectomy for tubal ectopic pregnancy A 12-years retrospective cohort study. Annali italiani di chirurgia 87:461–465

Rahn DD, Mamik MM, Sanses TVD et al (2011) Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in gynecologic surgery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 118:1111–1125. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318232a394

Gueli Alletti S, Rossitto C, Cianci S et al (2018) The Senhance™ surgical robotic system (“Senhance”) for total hysterectomy in obese patients: a pilot study. J Robot Surg 12:229–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-017-0718-9

Gueli Alletti S, Rossitto C, Perrone E et al (2017) Needleoscopic conservative staging of borderline ovarian tumor. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 24:529–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2016.10.009

Rossitto C, Gueli Alletti S, Rotolo S et al (2016) Total laparoscopic hysterectomy using a percutaneous surgical system: a pilot study towards scarless surgery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 203:132–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.007

Vitale SG, Gasbarro N, Lagana AS et al (2016) Safe introduction of ancillary trocars in gynecological surgery: the “yellow island” anatomical landmark. Annali italiani di chirurgia 87:608–611

Gueli Alletti S, Rossitto C, Cianci S et al (2016) Telelap ALF-X vs standard laparoscopy for the treatment of early-stage endometrial cancer: a single-institution retrospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 23:378–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2015.11.006

Chambers LM, Vargas R, Michener CM (2019) Sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial and cervical cancer: a survey of practices and attitudes in gynecologic oncologists. J Gynecol Oncol 30:e35. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2019.30.e35

Ballester M, Dubernard G, Rouzier R et al (2008) Use of the sentinel node procedure to stage endometrial cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 15:1523–1529. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-008-9841-1

Cignini P, Vitale SG, Laganà AS et al (2017) Preoperative work-up for definition of lymph node risk involvement in early stage endometrial cancer: 5-year follow-up. Updates Surg 69:75–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-017-0418-z

Capriglione S, Luvero D, Plotti F et al (2017) Ovarian cancer recurrence and early detection: may HE4 play a key role in this open challenge? A systematic review of literature. Med Oncol 34:164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-017-1026-y

Scaletta G, Plotti F, Luvero D et al (2017) The role of novel biomarker HE4 in the diagnosis, prognosis and follow-up of ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 17:827–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2017.1360138

Plotti F, Capriglione S, Terranova C et al (2012) Does HE4 have a role as biomarker in the recurrence of ovarian cancer? Tumour Biol 33:2117–2123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-012-0471-7

Plotti F, Scaletta G, Capriglione S et al (2017) The role of HE4, a novel biomarker, in predicting optimal cytoreduction after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 27:696–702. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000944

Angioli R, Plotti F, Capriglione S et al (2016) Preoperative local staging of endometrial cancer: the challenge of imaging techniques and serum biomarkers. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294:1291–1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4181-z

Angioli R, Plotti F, Aloisi A et al (2015) A randomized controlled trial comparing four versus six courses of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer patients previously treated with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy plus radical surgery. Gynecol Oncol 139:433–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.09.082

Paris I, Cianci S, Vizzielli G et al (2018) Upfront HIPEC and bevacizumab-containing adjuvant chemotherapy in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Hyperth. https://doi.org/10.1080/02656736.2018.1503346

Tozzi R, Giannice R, Cianci S et al (2015) Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy does not increase the rate of complete resection and does not significantly reduce the morbidity of Visceral-Peritoneal Debulking (VPD) in patients with stage IIIC–IV ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 138:252–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.05.010

Capriglione S, Plotti F, Montera R et al (2016) Role of paroxetine in the management of hot flashes in gynecological cancer survivors: results of the first randomized single-center controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol 143:584–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.006

Vitale SG, Caruso S, Rapisarda AMC et al (2018) Isoflavones, calcium, vitamin D and inulin improve quality of life, sexual function, body composition and metabolic parameters in menopausal women: result from a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Prz Menopauzalny 17:32–38. https://doi.org/10.5114/pm.2018.73791

Caruso S, Agnello C, Romano M et al (2011) Preliminary study on the effect of four-phasic estradiol valerate and dienogest (E2V/DNG) oral contraceptive on the quality of sexual life. J Sex Med 8:2841–2850. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02409.x

Caruso S, Cianci S, Vitale SG et al (2018) Sexual function and quality of life of women adopting the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS 13.5 mg) after abortion for unintended pregnancy. Eur J Contracept Reprod Heal Care 23:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2018.1433824

Funding

The work was not supported by any fund/grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scaletta, G., Quagliozzi, L., Cianci, S. et al. Management of postoperative chylous ascites after surgery for ovarian cancer: a single-institution experience. Updates Surg 71, 729–734 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-019-00656-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-019-00656-x