Abstract

The respiratory behaviour of baby corn - whole and end-cut, under different temperatures and gas conditions was evaluated to study its respiratory dynamics based upon enzyme kinetics. The dependence of respiration rate on the O2 and CO2 concentrations has been described assuming the enzyme kinetics model for combined type of inhibition caused by CO2. Various respiratory parameters viz. maximal O2 consumption rate Michaelis-Menten constants, Inhibition constants under the specified environmental conditions of 5, 12.5, 20°C and 75% relative humidity (RH) were estimated using non-linear regression technique. The enzyme kinetics parameters were analyzed according to Arrhenius law to study their temperature dependence. Based upon the overall analysis, it was found that storage temperature had substantial affect on the partial pressures within the closed containers and subsequently the respiration rates. The concentration of O2 inside the container and surrounding temperature had synergistic effect on the rate of respiration and respiratory parameters. Though the inhibition by evolved CO2 was observed to be of combined type, it changed from predominantly competitive at 5°C to predominantly uncompetitive at 12.5 and 20°C. This study can be utilized for design of modified atmosphere packages for storage of fresh and minimally processed baby corn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Baby corn (Zea mays L.) belongs to Gramineae family has revolutionised the food habits by providing diversified food items the world over. It comes as a delicacy when used as salad and its dressings, in soup, pickles, deeply fried with meat, rice and other vegetables. Baby corn production generally requires the cultivation practices recommended for normal corn production, except that the duration is only 60 days as compared to 110 to 120 days of grain crop. Farmers can grow 3–4 crops in a year and the by-products like tassel, husk silk and green stalk can be used as animal feed (Pandey et al. 2010). Baby corn is a young finger like unfertilised cobeau of maize with 1–3 cm emerged silk. The cobs 6–10 cm in length, 1–1.5 cm in diameter and 7–8 g in weight with regular rows are ideal for consumption. Harvesting can be started when the first silk has emerged about 0.5–1 cm i.e. from 1–3 days after silk emerges (Bar-Zur and Saadi 1990). Generally 5–6 pickings are required to harvest complete crop. Harvesting of cobs is most crucial as a delay of single day in picking certainly degrades the quality and taste of cobs. Baby corn is highly nutritive which is at par or even superior than some vegetables. Besides protein, vitamins and iron it is one of the rich source of phosphorous. Its 100 g cobs provide 0.2 g fat, 1.9 g protein, 8.2 mg carbohydrate, 28 mg calcium, 86 mg phosphorous and 64 fu vitamins, the remaining 89.1 percent being moisture (Hallauer 2000). For Indian climatic conditions, VL 42, an open pollinated variety, and MEH 114 (hybrid) have been recommended for baby corn production. In north India, the variety mainly being used for export purposes is G5414 (Hybrid). Hybrid varieties give 6–8 tonnes/ha husked cob yield.

Modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) is a well established technology which in combination with low temperature storage helps in extending the shelf life and maintenance of quality of perishable produce by the way of creation of appropriate gaseous atmosphere around the surrounding of the produce packaged in plastic films (Rai et al. 2011). The MAP is especially important for fresh-cut produce because of their greater susceptibility to water loss, cut surface browning, higher respiration rates, enhanced ethylene biosynthesis and action, and microbial growth (Gorny 1997). The MAP for fresh produce requires proper interaction of produce, packaging film and package parameters to arrive at optimum in-pack atmosphere. The design and generation of an optimum MA requires thorough understanding of the interaction between the various factors such as film characteristics (surface area, gas and water vapour permeability), temperature, free volume inside the package, weight and respiration rate of the produce and initial gaseous composition (Salvador et al. 2002).

Use of low O2 (1–5 %) and high CO2 (5–10 %) concentrations, in combination with low temperature storage maintains sensorial quality and extends the shelf life of fresh-cut vegetables (Fonseca et al. 2002; Moretti et al. 2003). Discolouration of cut surfaces due to enzymatic browning, yellowing of green vegetables, and pale colour of bright vegetables are the main defects of fresh-cut produce (Nobile et al. 2006). The risk of developing injurious gas concentrations can be decreased by placing pin holes, or microperforations, in the plastic film (Brar et al. 2011, Rai et al. 2011). The design of modified atmosphere packages requires knowledge of mass transport properties of polymeric films and the respiration rates of fresh produce placed inside the package.

The respiration is the process by which the stored organic materials (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) are broken down into simple end-products with the release of energy. Oxygen is used during this process and carbon dioxide is produced. This results in hastening of senescence, reduced food value for the consumer, loss of flavour and saleable weight. Respiration is a metabolic process that provides energy for plant biochemical processes. According to Lee et al. (1991) aerobic respiration consists of oxidative breakdown of organic reserves (carbohydrates, lipids and organic acids) to simpler molecules, including carbon dioxide and water with release of energy as follows (Eq. 1):

The rate of respiration depends upon various intrinsic (crop) and extrinsic (crop environment) factors. It is extremely difficult to maintain/control the intrinsic factors but relatively easier to alter the extrinsic ones i.e. gaseous concentrations in the crop environment, surrounding temperature and relative humidity. The concentrations of gaseous components viz. O2 and CO2 in the produce environment affects the rate of respiration and this effect has been described assuming mixed inhibition caused by CO2 using the enzyme kinetics model for combined type of inhibition. Peppelenbos and Van’t Leven (1996) proposed the following comprehensive relationship (Eq. 2) to describe the effect of inhibition (competitive, uncompetitive and non-competitive) on the rates of O2 consumption and this relationship has been successfully utilized by various scientists (Kaur et al. 2011) to evaluate the effect of inhibition by the evolved CO2 on the rate of respiration reaction.

Mixed inhibition encompasses a broad range of behaviour and for unambiguous interpretation has been further sub-divided into three types: predominantly competitive, noncompetitive and predominantly uncompetitive (Copeland 2000). Mixed inhibition as defined here encompasses such a broad range of behaviour that it may sometimes be helpful to subdivide it further. The case in which K mc < K mu may then be called predominantly competitive inhibition, the case with K mc = K mu may be called pure non-competitive inhibition, and the case with K mc > K mu may be called predominantly uncompetitive inhibition.

The most important external factor influencing respiration is the storage temperature. A two to three fold increase in biological reactions has been reported for every 10 °C rise in temperature within the range of temperatures normally encountered in the distribution and marketing chain. Arrhenius law has been widely used to describe temperature dependence of respiration rates (Fonseca et al. 2002; Kaur et al. 2011; Benkeblia 2004; Charles et al. 2005). All the parameters of enzyme kinetics model were evaluated using Arrhenius law [\( k = A{{e}^{{\frac{{ - {{E}_a}}}{{RT}}}}} \)] to study the effect of storage temperature. The values Arrhenius constant A and activation energy E a could be determined by plotting ln(k) against 1/T. The higher the E a , higher is the temperature dependence of the studied parameter. The parameters were analyzed according to Arrhenius law to describe their temperature dependence.

Many scientists have analyzed the respiratory behaviour of various fruits and vegetables at varying conditions of storage temperature and humidity (Emond et al. 1991; Fishman et al. 1995; Jacxsens et al. 2000; Geysen et al. 2005). Accounting for all the factors that affect respiration is rather complex. The important parameters that could be studied experimentally are gaseous concentrations, temperature, time, etc. (Talasila et al. 1991, Talasila et al. 1995; Fonseca et al. 2000). Linear relationships to describe the complex phenomenon of respiration in sharp contrast to the actual non-linearity of the enzyme kinetics reaction and its temperature dependence have been studied. More complex dynamic relationships have also been developed over the years to account for temporal changes in package volume, product respiration and the temperature and humidity of the environment. Few scientists have analyzed the data statistically with iterative non-linear regression routine (Hertog et al. 1998). Based on the fact that respiratory metabolism is governed by enzymatic reactions, many researchers have used the Michaelis-Menten type equation to describe the relation between respiration and gas concentration. As respiration is strongly affected by temperature, Arrhenius relationship has been incorporated in the Michaelis-Menten type equation. Michaelis-Menten equation is the most general form of the enzyme kinetics relation that assumes no inhibition of O2 consumption by the evolved CO2. But actually, the evolved CO2 may or may not inhibit the respiration reaction in some way or the other depending upon the storage conditions and produce characteristics. So, a model proposed by Peppelenbos and Van’t Leven (1996) based on the combined type of enzyme kinetics relationship that incorporates both competitive and uncompetitive parts of inhibition by CO2 appears more appropriate for study of respiration. The present study was undertaken to investigate the effect of environmental temperatures and minimal processing on the respiratory behaviour of fresh baby corn.

- A :

-

reaction rate constant

- Ea :

-

Activation energy, kJ mol -1

- i,f :

-

initial and final

- k :

-

Parameter whose temperature dependence is to be studied

- \( {{K}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) :

-

Michaelis-Menten constant for oxygen consumption, %

- \( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) :

-

Michaelis-Menten constant for competitive inhibition of O2 consumption by CO2, %

- \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) :

-

Michaelis-Menten constant for uncompetitive inhibition of O2 consumption by CO2, %

- \( p_{{{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) :

-

oxygen concentration in the container headspace, kPa

- \( p_{{C{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) :

-

carbon dioxide concentration in the container headspace, kPa

- R:

-

gas constant = 8.314 J K -1 mol -1

- \( {{R}_{{{{O}_2}}}} \) :

-

Oxygen consumption rate, ml kg -1 h -1

- \( {{R}_{{C{{O}_2}}}} \) :

-

CO2 evolution rate, ml kg -1 h -1

- RQ:

-

Respiration quotient

- T :

-

temperature, K

- t :

-

time, h

- ρ s :

-

Mean density of baby corn, kg l -1

- \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) :

-

Maximum oxygen consumption rate, ml kg -1 h -1

- V s :

-

Volume of baby corn kept for respiration, l

- V t :

-

total inside volume of the container used for respiration, l

- V v :

-

void volume of the container, l

- W :

-

Weight of baby corn kept in impermeable container for respiration, kg

- W s :

-

Weight of baby corn used for density determination using water displacement method, kg

Materials and methods

Unhusked fresh baby corn (Zea mays L., cv. Syngenta G5414 hybrid) was procured from farms of Field Fresh Foods Pvt. Ltd, India. The fresh produce was then equilibrated at experimental conditions for two hours before the start of respiration experiment.

Sample preparation

Unhusked fresh baby corn (Zea mays L., cv. Syngenta G5414 hybrid) was procured from farms of Field Fresh Foods Pvt. Ltd, India. The fresh produce was then equilibrated at experimental conditions for two hours before the start of respiration experiment. The fresh baby corn samples were peeled using a slitter/blade to slit the outer husk without damaging the cob manually. The husk, hair and stalks were then removed manually without damaging the cob. The uniform cobs after removal of stalks attached were considered as whole baby corn samples. The cob of uniform size were taken and sized on the basis of length to 8 cm for end cut baby corn samples.

Evaluation of respiration rate

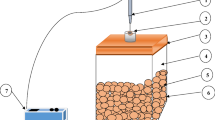

The void volume (V v ) for each experiment was determined using the relationship (Eq. 3)

The total inside volume (V t ) of the impermeable glass containers used for respiration experiment was measured. For each experiment, the volume of sample filled in the impermeable container was determined using the relationship (Eq. 4)

The density of fresh baby corn (husked) was determined by water displacement method through the evaluation of true volume of a known mass of fresh baby corn (Ishikawa et al. 1992).

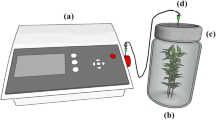

The respiration study was conducted by placing approximately 400 g of fresh baby corn sample in each of the three impermeable glass containers. The containers were tightly sealed using vacuum grease to avoid any leakage during experiment. Tightly-sealed containers were then placed in an environmental chamber (Blue Star, India). Three different temperatures viz. 5, 12.5 and 20 °C, and constant relative humidity of 75 % was used. The container headspace was continuously monitored to determine the O2 and CO2 concentrations at regular intervals using a gas analyzer (Quantek Instruments, USA). Gas analyses were continued till the difference between two consecutive concentrations in the headspace became almost constant. Oxygen consumption rate and carbon dioxide evolution rate were found out as per Eqs. 5 and 6.

The headspace partial pressures and respiration rates were studied at three selected storage temperatures using MS-Excel Software. The experimentally determined respiration rates and partial pressures of O2 and CO2 were subsequently used to determine various parameters of the enzyme kinetics model by non-linear regression analysis (GraphPad PRISM® Version 5.00.288 software, GraphPad Software Inc., USA).

Results and discussion

Respiratory dynamics of fresh baby corn

The respiratory dynamics of fresh baby corn in whole and end-cut form was studied in terms of the headspace partial pressures of \( p_{{{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) and \( p_{{C{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) inside the impermeable glass containers containing baby corn samples and maintained at different temperatures. For both whole and end-cut baby corn, a gradual decrease was observed in \( p_{{{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) with the progress of time (Fig. 1), whereas, the values of \( p_{{C{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) increased during the same interval at 5 and 12.5 °C temperatures. However, steep trends were observed at the higher temperature of 20 °C. The values of \( p_{{{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) and \( p_{{C{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) arrived at steady state conditions within 3, 3.5 and 4 hours at the temperatures of 5, 12.5 and 20 °C. The rates of decrease of \( p_{{{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \) and increase of \( p_{{C{{O}_2}}}^{{in}} \), increased with increase in environmental temperature. The difference in steady-state headspace O2 and CO2 partial pressures decreased as the surrounding temperature was increased from 12.5 to 20 °C. Throughout the respiration study, both O2 and CO2 partial pressures remained within the aerobic respiration range and no fermentation was observed. The calculated values of \( {{R}_{{{{O}_2}}}} \) and \( {{R}_{{C{{O}_2}}}} \) for whole and end-cut baby corn during the same interval are plotted in Fig. 2. Irrespective of the form of baby corn, the rates of respiration were higher at the start of experiment and gradually decreased as the storage period increased before becoming almost constant. For whole baby corn, the rate of oxygen consumption were 103.91, 145.48 and 242.46 ml kg-1 h-1 at temperatures of 5, 12.5 and 20 °C at the start of experiment and stabilized at 53.69, 66.68 and 113.44 ml kg-1 h-1 with the attainment of steady-state. The steady-state respiration rates for CO2 evolution at same temperatures were 24.25, 31.78 and 65.55 ml kg-1 h-1, respectively. For end-cut baby corn, the rates of O2 consumption at the onset of experiment were 109.66, 157.64 and 418.10 ml kg-1 h-1 before finally stabilizing at 58.26, 72.82 and 171.35 ml kg-1 h-1 at temperatures of 5, 12.5 and 20 °C, respectively. The rates for CO2 evolution stabilized at 23.99, 32.56 and 83.99 ml kg-1 h-1 at same temperatures, respectively. The steady-state O2 consumption rate increased by 24.19 % and 24.99 %, respectively for whole and end-cut baby corn when temperature was increased from 5 to 12.5 °C but a substantial increase of 70.13 % and 135.31 %, was observed when temperature was increased from 12.5 to 20 °C. For similar temperature increments, increase in CO2 evolution rate was observed to be 31.05 and 106.26 %, respectively for whole and 35.72 % and 157.95 % for end-cut baby corn, respectively. The difference in O2 consumption rate and CO2 evolution rate increased gradually with increase in temperature indicating an increase in water vapour production (Fig. 2). This can be attributed to condensation of moisture taking place within impermeable containers/packages of fresh produce at high temperatures which is also major cause spoilage of produce. At all temperatures, the O2 consumption rate remained higher than the CO2 evolution rate giving steady-state respiration quotient values as 0.45, 0.44 and 0.62 at 5, 12 and 20 °C, respectively.

Evaluation of respiration and inhibition using enzyme kinetics theory

The non-linear analyses of respiration data on the basis of enzyme kinetics model for combined inhibition led to the determination of various enzyme kinetics parameters, viz. \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \), \( {{K}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \), \( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) and \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) which are presented in Table 1.

Effect of O2 on respiration

\( {{K}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) is a measure of saturation of respiration with headspace O2. It represents the oxygen concentration at which half the maximum respiration rate is reached, assuming no inhibition by CO2. Values of \( {{K}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) (Table 1) at all temperatures showed that fresh baby corn showed a steep incline in respiration with respect to O2 and temperature.

Inhibition of respiration by CO2

The value of inhibition constants is a measure of the extent to which respiration can be inhibited by CO2. A high value for inhibition constants implies that the backward reaction of the inhibition is much faster than the forward reaction and hence inhibition by CO2 is not possible. The inhibition constants obtained by non-linear analyses of the respiration data shows that respiration of fresh and end-cut baby corn was prone to combined inhibition (\( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \)and \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) are finite and unequal). At 5 °C predominantly competitive type (\( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} < {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \)) of combined inhibition was observed. However at 12.5 °C and 20 °C, predominantly uncompetitive type of combined inhibition (\( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) and \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) are finite and unequal; \( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} > {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \)) was observed. Inhibition is said to be predominantly competitive if the inhibitor, CO2 in the present study, reversibly binds to the same site as the substrate (O2), so its inhibition can be entirely overcome by using a very high concentration of O2. The maximum velocity of the enzyme doesn't change (if you give it enough O2), but it takes more O2 to get to half maximal activity. But in this experiment at 5 °C, no extra O2 is given and low level of O2 is attained within a few hours, half the maximum velocity of reaction is considerably reduced. The O2 versus RO2 (Fig. 3) curve is shifted to the left but not down. Inhibition is said to be predominantly uncompetitive if the inhibitor (CO2) binds with equal affinity to the enzyme, and the enzyme-O2 complex. The inhibition is not surmountable by increasing substrate concentration. Because the enzyme-O2 complex is stabilized, it ta\( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \)kes less O2 to get to half-maximal activity. This suggests that when inhibition becomes uncompetitive at 12.5 °C and beyond, even at low O2 concentrations that are attained within a few hours, the value of half maximum activity is attained. The O2 versus RO2 curve is shifted to the left and also down. A glance at the Fig. 3 suggests that as the temperature was increased from 12.5 to 20 °C; the downward shift became more prominent, indicating that inhibition changed from competitive to uncompetitive, probably due to denaturization of enzyme (protein) at high temperature. Not much difference in values of \( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) and \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) was observed for whole baby corn when temperature was increased from 5 °C to 20 °C. The value of \( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) was observed to be slightly less than that of at 5 °C but became slightly more than that of \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) beyond 12.5 °C (Table 1).

Effect of temperature on respiration

Many researchers have reported the temperature dependence of only \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) or respiration rates (Jacxsens et al. 2000; Geysen et al. 2005; Hertog et al. 1998; Benkeblia 2004). The temperature dependence of the respiratory parameters is indicated in the Table 1 by an increase in the values of all enzyme kinetics parameters with increase in temperature. The activation energies for enzyme kinetics parameters, namely, \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \), \( {{K}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \), \( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) and \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) were determined using Arrhenius relationship to explain the temperature dependence of these parameters.

For whole baby corn, \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) increased by 59.78 % and by 18.60 % with an increase of temperature from 5 to 12.5 °C and 12.5 °C to 20 °C, respectively. \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) was observed to be less temperature-dependent than \( {{K}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \), \( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) and \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \), as expressed by its lower activation energy (E a = 28.64 kJ mol-1). \( {{K}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) was observed to be highly temperature dependent (E a = 589.37 kJ mol-1) as compared to the inhibition constants [E a (\( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \)) = 49.25 kJ mol-1; E a (\( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \)) = 48.78 kJ mol-1], although the dependence was inverse in nature. For end-cut baby corn, \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) showed a rise of 79.53 and 163.13 % for the same temperature range. The results thus indicate that below a temperature of 12.5 °C, minimal processing had less effect on half maximal rate but beyond 12.5 °C, temperature and minimal processing had synergistic effect on \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) (163.13 % increase for end-cut compared to 18.60 % for whole baby corn).

Conclusion

The present study described the effect of headspace gaseous concentrations, CO2 inhibition, environmental temperature and minimal processing on the respiratory parameters of baby corn. The difference in steady-state headspace O2 and CO2 partial pressures decreased as the surrounding temperature was increased from 5 to 20 °C. The difference in O2 consumption rate and CO2 evolution rate increased gradually with increase in temperature indicating an increase in water vapour production. For whole baby corn, the steady state O2 consumption rates were 53.69, 66.68 and 113.44 ml kg-1 h-1 in comparison to 58.26, 72.82 and 171.35 ml kg-1 h-1 for end cut baby corn at temperatures of 5, 12.5 and 20 °C, respectively. The steady-state CO2 evolution rates were 24.25, 31.78 and 65.55 ml kg-1 h-1 for whole baby corn in comparison to 23.99, 32.56 and 83.99 ml kg-1 h-1 for end cut baby corn at same temperatures, respectively. The steady-state O2 consumption rate increased by 24.19 % and 24.99 %, respectively for whole and end-cut baby corn when temperature was increased from 5 to 12.5 °C but a substantial increase of 70.13 % and 135.31 %, was observed when temperature was increased from 12.5 to 20 °C. For similar temperature increments, increase in CO2 evolution rate was observed to be 31.05 and 106.26 %, respectively for whole and 35.72 % and 157.95 % for end-cut baby corn, respectively. Beyond the temperature of 12.5 °C, O2 depletion, CO2 evolution and water vapour production enhanced substantially. Non linear regression analyses of the respiration data showed that enzyme kinetics relationship assuming mixed inhibition by CO2 explained the effect of headspace gaseous concentrations. All enzyme kinetics parameters viz. \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \), \( {{K}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \), \( {{K}_{{m{{c}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \) and \( {{K}_{{m{{u}_{{C{{O}_2}}}}}}} \)were found to be dependent on temperature and minimal processing.

This research has focused on respiratory behavior of fresh baby corn within temperature range commonly encountered during transportation and retail distribution 5–20 °C. The dependence of respiration rate on the headspace O2 and CO2 concentrations has been described assuming the enzyme kinetics model for combined type of inhibition proposed by Peppelenbos and Van’t Leven (1996). The effect of surrounding temperature on the respiratory parameters has been evaluated using the Arrhenius relationship (Fonseca et al. 2002; Benkeblia 2004; Charles et al. 2005; Kaur et al. 2011). The changes in the respiratory parameters on account of minimal processing have also been discussed. The results of the study have implied that the respiration rate of fresh baby corn can be kept low by storing it at a temperature less than 12.5 °C because this is the limiting temperature beyond which the inhibition by CO2 turns uncompetitive. Also the effect of minimal processing is more pronounced beyond 12.5 °C as indicated by 163 % increase in \( {{V}_{{{{m}_{{{{O}_2}}}}}}} \)for end-cut baby corn compared to 18 % for whole baby corn. This research substantiates the research work done by many other scientists who have also highlighted the role proper headspace atmospheres in delaying senescence, maintaining physico-chemical constituents and extending of shelf-life of different crops. Use of low O2 (1–5 %) and high CO2 (5–10 %) concentrations, in combination with storage at low temperatures maintains sensorial as well as microbial quality of fresh-cut vegetables (Fonseca et al. 2002; Moretti et al. 2003). These conditions inhibit enzymatic browning reaction on the cut surfaces and the structure of plant tissue sustains its typical turgoricidy and crispness for a longer period. Thus, temperature control and atmospheric modifications (low O2: 1–5 % and high CO2: 5–10 %) help to maintain produce quality by reducing respiration rate and enhance shelf-life by minimizing the adverse effects of cutting in fruits and vegetables. Utilization of the results of this research would be of immense help in proper designing of modified atmosphere packages for storage and transportation of this highly perishable produce throughout the value chain to urban retail markets.

References

Bar-Zur A, Saadi H (1990) Prolific maize hybrids for baby corn. J Hort Sci 65(1):97–100

Benkeblia N (2004) Effect of maleic hydrazide on respiratory parameters of stored onion bulbs (Allium cepa L.) Braz. J Plant Physiol 16(1):47–52

Brar JK, Rai DR, Singh A, Kaur N (2011) Biochemical and physiological changes in Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum- graecumL.) leaves during storage under modified atmosphere packaging. J Fd. Sci Technol. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0390-4

Charles F, Sanchez J, Gontard N (2005) Modeling of active modified atmosphere packaging of endives exposed to several postharvest temperatures. J Fd Sci 70:443–449

Copeland RA (2000) Enzymes - a practical introduction to structure, mechanism and data analysis, 2nd edn. Wiley-VCH, Germany

Emond JP, Castaigne F, Toupin CJ, Desilets D (1991) Mathematical modeling of gas exchange in modified atmosphere packaging. Trans ASAE 34:239–245

Fishman S, Rodov V, Peretz J, Ben-Yehoshua S (1995) Model for gas exchange dynamics in modified atmosphere packages. J Fd Sci 61:956–961

Fonseca SC, Oliveira FAR, Brecht JK (2002) Modeling respiration rate of fresh fruits and vegetables for modified atmosphere packages: a review. J Food Engg 52:99–119

Fonseca SC, Oliveira FAR, Lino IBM, Brecht JK, Chau KV (2000) Modeling O2 and CO2 exchange for development of perforation–mediated modified atmosphere packaging. J Fd Engg 43:9–15

Geysen S, Verlinden BE, Conesa A, Nicolai BM (2005) Modelling respiration of strawberry (cv. Elsanta) as a function of temperature, carbon dioxide, low and superatmospheric oxygen concentration. Frutic 05, 12–16 September 2005, Montpellier, France

Gorny JR (1997) A summary of CA and MA requirements and recommendations for fresh cut (minimally processed) fruits and vegetables, pp 30–66, In: Gorney J (ed) CA’97 Proceedings vol. 5, Fresh cut fruits and vegetables and MAP. Univ. California. Postharvest Hort. Ser. 19

Hallauer AR (2000) Specialty corns, 2nd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Hertog MLATM, Peppelenbos HW, Evelo RG, Tijskens LMM (1998) A dynamic and generic model of gas exchange of respiring produce: the effects of oxygen, carbon dioxide and temperature. Postharvest Biol and Technol 14:335–349

Ishikawa Y, Sato H, Ishitani T, Hirata T (1992) Evaluation of broccoli respiration rate in modified atmosphere packaging. J Pack Sci Technol 1:143–153

Jacxsens L, Devlieghere F, Rudder TD, Debevere J (2000) Designing equilibrium modified atmosphere packages for fresh-cut vegetables subjected to changes in temperature. LWT 33:178–187

Kaur P, Rai DR, Paul S (2011) Nonlinear estimation of respiratory dynamics of fresh-cut spinach (Spinacia Oleracea) based on enzyme kinetics. J of Fd Process Engg. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4530.2009.00508.x

Lee DS, Haggar PE, Lee J, Yam KL (1991) Model for fresh produce respiration in modified atmospheres based on the principles of enzyme kinetics. J Fd Sci 56(6):1580–1585

Moretti CL, Arajulo AL, Mattos LM (2003) Evaluation of different oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen combinations employed to extend the shelf life of fresh-cut collard greens. Hort Brass 21:676–680

Nobile MAD, Biaiano A, Benedetto A, Massignan L (2006) Respiration rate of minimally processed lettuce as affected by packaging. J Food Engg 74(1):60–69

Pandey M, Sudhir K, Ahuja R and Tewari D (2010) Field fresh foods: could baby corn create the platform for a big agribusiness? Yale Case :10–036

Peppelenbos HW, Van’t Leven J (1996) Evaluation of four types of inhibition for modeling influence of carbon dioxide on oxygen consumption of fruits and vegetables. Postharvest Biol Technol 7:27–40

Rai DR, Chadha S, Kaur MP, Jaiswal P, Patil RT (2011) Biochemical, microbiological and physiological changes in Jamun (Syzyium cumini L.) kept for long term storage under modified atmosphere packaging. J Fd. Sci Technol 48(3):357–365

Salvador ML, Jaime P, Oria R (2002) Modeling of O2 and CO2 exchange dynamics in modified atmosphere packaging of burlet cherries. J Fd Sci 67:231–235

Talasila PC, Chau KV, Brecht JK and Emond JP (1991) A mathematical model for modified atmosphere packaging of fruits and vegetables. American Society Agricultural Engineers No. 91–6022:16

Talasila PC, Chau KV, Brecht JK (1995) Modified atmosphere packaging under varying surrounding temperatures. Trans ASAE 38(3):869–76

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support in form of Research Associateship provided by Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India for carrying out this research study. The authors are also grateful to Field Fresh Foods Pvt. Ltd., India for providing the required crop material as and when required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, M., Kumar, A. & Kaur, P. Respiratory dynamics of fresh baby corn (Zea mays L.) under modified atmospheres based on enzyme kinetics. J Food Sci Technol 51, 1911–1919 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-012-0735-7

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-012-0735-7