Abstract

Shared decision-making (SDM) helps patients weigh risks and benefits of screening approaches. Little is known about SDM visits between patients and healthcare providers in the context of lung cancer screening. This study explored the extent that patients were informed by their provider of the benefits and harms of lung cancer screening and expressed certainty about their screening choice. We conducted a survey with 75 patients from an academic medical center in the Southeastern U.S. Survey items included knowledge of benefits and harms of screening, patients’ value elicitation during SDM visits, and decisional certainty. Patient and provider characteristics were collected through electronic medical records or self-report. Descriptive statistics, Kruskal–Wallis tests, and Pearson correlations between screening knowledge, value elicitation, and decisional conflict were calculated. The sample was predominately non-Hispanic White (73.3%) with no more than high school education (53.4%) and referred by their primary care provider for screening (78.7%). Patients reported that providers almost always discussed benefits of screening (81.3%), but infrequently discussed potential harms (44.0%). On average, patients had low knowledge about screening (score = 3.71 out of 8) and benefits/harms. Decisional conflict was low (score = − 3.12) and weakly related to knowledge (R= − 0.25) or value elicitation (R= − 0.27). Black patients experienced higher decisional conflict than White patients (score = − 2.21 vs − 3.44). Despite knowledge scores being generally low, study patients experienced low decisional conflict regarding their decision to undergo lung cancer screening. Additional work is needed to optimize the quality and consistency of information presented to patients considering screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lung cancer screening with low-dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) has been proven through rigorously conducted randomized clinical trials [1, 2] to reduce lung cancer mortality when conducted in high-risk populations annually. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated their guidance for lung cancer screening in March 2021, expanding eligibility to include individuals aged 50–80 years who have a 20 + pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years [3]. This change expands the population eligible for lung cancer screening by 86% and has the opportunity to reduce known sex and racial disparities in eligibility for lung cancer screening [4].

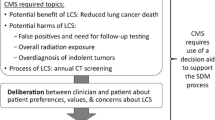

Although screening can reduce lung cancer mortality through detection of lung cancers at earlier, more treatable stages, potential harms include overdiagnosis, false positive test results, and risk of invasive diagnostic procedures and related complications. Given this risk–benefit profile of screening, it is recommended that individual screening decisions be based upon informed and value-based discussions with one’s healthcare provider. This discussion, often referred to as shared decision-making (SDM), is a critical element of the screening process and is mandated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for reimbursement [5].

Prior research has shown that patients are not always informed, nor certain about whether lung cancer screening is right for them [6]. In a pragmatic trial where patients watched an online informational video about LDCT screening delivered via a patient portal, Dharod et al. found that about 30% of eligible patients [7] wanted lung cancer screening, 44% were unsure, and 25% declined screening. Through independent observation of SDM visit transcripts, Brenner et al. [8] also found that screening discussions with patients were less than 1 min in length on average, did not use decision aids or other education materials, and rarely included a discussion of harms. Shen et al. found that smoking cessation resources and/or referrals were also low in SDM visits, despite being one of many components required by CMS [9].

Given the stated concerns about the potential quality of SDM discussions and providers’ time constraints and competing demands [10,11,12,13,14,15], some have argued that SDM is a barrier to LDCT screening and/or may not be worth the costs [16]. Others advocate that SDM visits and associated reimbursement requirements should continue, albeit with more consistent and balanced messaging about screening from providers [17]. More information is needed to understand how well patients are currently being educated of the risks and benefits of lung cancer screening to inform development of future provider and patient interventions. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore how patients who have been referred for LDCT screening by their healthcare provider describe the SDM visit, including what information they learned about screening and their level of certainty about their screening decision.

Material and Methods

Patient Eligibility

We conducted the study in a large academic health system located in central North Carolina, U.S. The health system has more than 2 million outpatient visits yearly. We queried the medical center’s electronic health record (EHR) to identify patients who were referred for LDCT screening. We excluded patients who were flagged in the EHR as needing an interpreter. Patients were excluded if they were referred for a diagnostic chest CT, had a prior history of lung cancer, or had completed an LDCT screening in the past. We contacted potentially eligible patients within 10 business days after their LDCT was ordered.

Questionnaire

Patients were asked to complete a 59-item questionnaire over the telephone to assess their knowledge of the benefits and potential harms of LDCT screening, experience discussing LDCT screening with their healthcare provider, and preparedness to undergo LDCT screening. In this analysis, we leveraged specific questionnaire sections, including the eligibility confirmation section, the demographics section, and items taken or adapted from the Brief Knowledge Measure scale [18], the values elicitation OPTION scale [19], and the Decisional Conflict Sure Tool scale [20]. Items were typically on a 5-point Likert scale, except for knowledge-related items, which had 3 categorical response options (i.e., true, false, and “I don’t know”). The complete questionnaire with remaining sections is provided in the Appendix A.

Survey Protocol

Study surveys were programmed in the Research Electronic Data Capture system (REDCap) and conducted by telephone. REDCap is a secure web application for managing surveys and associated databases. For patients who consented to participate, we collected additional clinical and demographic data from the EHR including age, gender, asthma diagnosis, COPD diagnosis, race/ethnicity, health insurance type, smoking status, and whether the patient completed LDCT screening within 90 days of their shared decision-making visit.

Participants required 12–20 min to answer all survey questions. The Flesch-Kincaid grade level of the questionnaire was 7.6. Interviews were conducted between May 1st, 2020, and September 30th, 2020. The research team made attempts to contact 344 eligible patients, of which 147 were reached by phone within 3 call attempts. A total of 81 patients consented to participate, and from those, 75 completed the questionnaire and comprised the final analytic sample.

The study was approved under expedited review (45 CFR 46 — categories #5 and #7) by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of South Carolina and Wake Forest University.

Data Transformations and Analysis

To calculate the decisional conflict and knowledge scores, we followed procedures outlined by Elwyn et al. and Lowenstein et al., respectively [18, 19]. For the decisional conflict items, Elwyn et al. used Disagree-Neutral-Agree response options while we used 5-point Likert scale for consistency with other survey items [19]. To mirror the decisional conflict score calculation of Elwyn et al., we assigned a value of 1 to “Strongly Disagree” and “Disagree” answers, a value of 0 for “Neutral” answers, and a value of − 1 to “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” answers. We then summed the values for each participant to obtain their final decisional conflict score, ranging from − 4 (least decisional conflict) to 4 (most decisional conflict).

For the knowledge-related items, we tabulated the counts and proportions of participants answering correctly or answering incorrectly/“I don’t know” for each question. We also created a knowledge score for each study participant by summing the number of knowledge questions they answered correctly, for a maximum score of 8 [19].

As previously established [19], we created a value elicitation score from the questions in the values elicitation section. We assigned a value of 0 to “Strongly Disagree,” 1 to “Disagree,” 2 to “Neutral,” 3 to “Agree,” and 4 to “Strongly Agree” answers, for each patient. We then summed the values and scaled them to 100 for each participant to obtain their value elicitation score.

For the value elicitation, knowledge, and decisional conflict scores, we calculated the mean and standard deviation for the study sample, overall and stratified by referring provider type (i.e., primary care provider vs. specialist) and sociodemographic characteristics. We used the Kruskal–Wallis (KW) test (a non-parametric one-way ANOVA) to evaluate significant differences in each outcome (\(\alpha\) level = 0.05) across sociodemographic groups. We calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between decisional conflict and value elicitation quality as well as with knowledge. We also calculated correlation between value elicitation quality and knowledge.

Results

Our final sample of patients who completed the survey corresponded to an overall response rate of 21.5%. Table 1 shows the characteristics of study participants. The average age was 63.6 years old. Most participants (59/75, 79%) were referred for screening by their primary care provider compared to 19% (14/75) referred by their pulmonologist. One participant was referred by their cardiologist and another by a different type of provider. Men and women were nearly identically represented. Participants’ most common educational attainment level was high school or GED (38.7%) and they were often unemployed or unable to work (40%). Private insurance (37.3%) and Medicare (46.7%) were the insurance types most frequently held by study subjects. Almost three-quarters (73.3%) of participants identified as non-Hispanic White. Our sample characteristics were similar to eligible patients who did not participate in the study: average age 63.6, 48.3% women, 30.1% with private insurance, 53.5% with Medicare coverage, 77.0% non-Hispanic White, and 65.8% current smokers.

Table 2 shows that participants had varied responses to statements describing the quality of their value elicitation with their provider. Participants reported that providers most commonly neglected to explain the risks of screening (49.3%), followed by failing to explain that choosing not being screened is an option (41.9%) and failing to explain all the options for screening (33.3%). Agreement was highest for reporting that one’s healthcare provider gave opportunities to ask questions (96%) and explaining why the screening was being recommended to the participant (93.3%). The average value elicitation score was 66.8 out of 100 (standard deviation [SD]: 18.1).

Overall, the mean percentage of correct answers for knowledge questions was 46% (3.71 correct answers out of 8 total questions, SD: 1.52). Table 3 shows that only two questions were answered correctly by over half of the participants (“Without screening, lung cancer is often found at a later stage when a cure is less likely” and “A CT scan can find lung disease that is not cancer”).

Although mean knowledge scores were low, participants generally displayed low decisional conflict, as shown in Table 4. In the four items of the decisional conflict scale, most participants either agreed or strongly agreed that they were making the best choice for themselves, knew about the risks/benefits of screening, and had support to make their decision. The average decisional conflict score was − 3.12 (SD: 1.53, Table 5).

Decisional conflict was weakly correlated with value elicitation quality (R= − 0.27, p = 0.02), as well as with knowledge (R= − 0.25, p = 0.03). There was no significant correlation between knowledge and value elicitation quality (R= 0.19, p = 0.10).

In Table 5, the KW test revealed no statistically significant differences in knowledge score across demographic characteristics or referring provider. The KW test revealed a significant difference in decisional conflict between non-Hispanic Black and White participants (p = 0.02). Black participants experienced more decisional conflict (score = − 2.21) than White participants (score = − 3.44). The difference in mean decisional conflict score between the two groups was 1.23. While not significant, we observed that mean knowledge and value elicitation scores increased with education levels (p = 0.13 and p = 0.05, respectively). Specifically, the value elicitation score went from 55.1 for patients without a high school diploma to 75.6 for those with a college degree or higher. The average knowledge score increased from 2.91 for patients without a high school diploma to 4.46 for those with a college degree or higher.

Discussion

Shared decision-making can help patients make more informed, engaged, and preference-sensitive decisions about their healthcare through bidirectional information exchange and deliberation with their clinical providers. Despite several intervention studies showing positive outcomes when patients and providers engage in shared decision-making, often including decision aids [20, 21], little is known about how shared decision-making for LDCT screening is conducted in real-world settings [8]. In our study, patients reported that while providers almost always discussed the benefits of screening, they infrequently discussed potential harms or explained that not being screened was also an option. On average, patients had low knowledge about lung cancer screening and its benefits and potential harms. Despite this, their decisional conflict was low and only weakly related to knowledge or value elicitation (i.e., a proxy for engagement).

Prior research shows that healthcare providers need to be better informed about lung cancer screening guidelines, its potential risks and benefits, and costs [11, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Although studies indicate clinicians’ knowledge of lung cancer screening has improved over time [29], this improvement has not necessarily translated to more informed and balanced counseling with high-risk patients. In a content analysis of conversations between patients and their healthcare providers at a different institution, Brenner et al. found that the mean time discussing lung cancer screening was only 59 s (8% of total visit time), with no evidence that decision aids or other educational guides were utilized in a primary care setting [8]. In a study by Eberth et al., most physicians reported they would be unlikely to engage in shared decision-making if the discussion took more than 5 min [10]. These findings reflect the time constraints providers commonly report as a barrier to engaging in shared decision-making and referring patients for screening [11, 14, 30, 31], as well as the (mis)perception that patients would be confused by or prefer not to have an in-depth discussion about lung cancer screening that included numerical data [12, 14]. Related to the quality of shared decision-making discussions, numerous studies including ours [6, 32, 33] have found that patients referred for lung cancer screening have limited understanding of any its potential harms. Similar to our study, Nishi et al. found harms were less likely to be addressed by the patients’ healthcare provider than the benefits of lung cancer screening (20.8% vs. 68.3%, respectively) [6]. Raju et al. also found most of the patients surveyed within their institution were not aware of any screening harms [32]. A limited understanding of the harms of screening may contribute to patients’ motivation to be screened, but it may also bias their decision-making [33]. An overemphasis on the positive aspects of screening was confirmed in our study and suggests a need for better patient education. Notably, we found that 81.33% of study participants agreed or strongly agreed that their provider explained benefits of screening, compared to 44% for risks of screening.

Better strategies for educating patients about the potential benefits and harms of lung cancer screening are needed. Given the highly variable and incomplete nature of shared decision-making, opportunities to develop and integrate decision aids into routine clinical practice should be explored. Conveying both the benefits and potential harms to patients is imperative, since not all patients will benefit equally from screening depending on their age, smoking history, comorbidities, family history, and other unique characteristics [34, 35]. Brief clinic-based decision aids can reduce both provider and patient knowledge gaps and streamline the shared decision-making process, particularly in primary care settings where providers are handling many competing health priorities [30]. Decision coaching has also been effectively used to help patients make informed screening choices without significantly increasing visit time [36].

Given concerns about patient-provider communication and time constraints on healthcare teams, opportunities to leverage technology and educational tools are warranted. One such program utilized an online-administered conjoint valuation survey followed by a brief educational narrative to help patients consider their lung cancer screening options and make the best choice for them [37]. This intervention reduced decisional conflict, suggesting that such tools can help individuals make the best choice for them without (or in addition to) traditional patient-provider deliberation. Similarly, tools like shouldiscreen.com [38] have been shown to improve patients’ knowledge about screening, reduce decisional conflict, and increase the concordance between individuals’ preferences and their screening eligibility [39]. Despite the broad appeal and use of shouldiscreen.com, Lau et al. have argued for more diverse delivery modes to support patients with varied educational attainment, as well as health and computer literacy [39]. Caverly and Hayward also argue for simplifying the shared decision-making process; rather than go over all the risks and benefits with every patient in the office, patients receive an individualized recommendation based on their risk profile, with much of the data gathered before the visit electronically [40]. Dubbing their patient-centric approach “everyday SDM,” Caverly and Hayward suggest this approach is more feasible for time-constrained providers [40]. In support of this approach, the team developed a tool (screenLC.com) that can be used by providers to determine whether the patient’s decision to get lung cancer screening is likely to be “preference-sensitive” given individuals’ varied risk–benefit profiles [41].

Although our study is among a handful that have explored shared decision-making quality and outcomes in a real-world clinical setting, limitations are present. First, the sample included only English-speaking patients from one academic medical center in the Southeastern U.S. Second, due to the pilot nature of the study, we limited our sample size to only 75 individuals. A strength of our study is the non-parametric statistical approach to handle the small sample size, as well as the use of validated scales to measure knowledge, decisional conflict, and value elicitation.

Conclusions

Additional work is needed to optimize the quality and consistency of information presented to patients when educating them about lung cancer screening. In this study, patients infrequently reported having a balanced discussion of the risks and benefits of lung cancer screening with their healthcare provider, reflected in their low average knowledge scores. Despite this, most patients (particularly those who are non-Hispanic White) felt certain about their screening choice. To help ensure patients make a well-informed choice about screening, where their values are taken into consideration, healthcare providers and their teams need continued education about the nuances of lung cancer screening and how to best conduct shared decision-making. In addition, policies or practice changes that facilitate these best practices are needed including but not limited to using decision aids, leveraging risk prediction models/tools, and increasing reimbursement for and/or allotted provider time to conduct shared decision-making with patients.

Data Availability

All data and materials as well as software application or custom code support published claims and comply with field standards.

Code Availability

Available upon request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- CMS:

-

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- KW:

-

Kruskal–Wallis

- LDCT:

-

Low-dose computed tomography

- REDCap:

-

Research Electronic Data Capture system

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SDM:

-

Shared decision-making

- USPSTF:

-

US Preventive Services Task Force

References

Aberle D, Adams A, Berg C et al (2015) Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 365(5):2155–2165. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0707943

de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA et al (2020) Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med 382(6):503–513. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1911793

Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM et al (2021) Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 325(10):962–970. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1117

Meza R, Jeon J, Toumazis I et al (2021) Evaluation of the benefits and harms of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 325(10):988–997. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1077

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography. Medicare Coverage Database. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274. Published 2015

Nishi SPE, Lowenstein LM, Mendoza TR et al (2021) Shared decision making for lung cancer screening: how well are we “sharing”? Chest May:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.041

Dharod A, Bellinger C, Foley K, Case LD, Miller D (2019) The reach and feasibility of an interactive lung cancer screening decision aid delivered by patient portal. Appl Clin Inform 10(1):19–27. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1676807

Brenner AT, Malo TL, Margolis M et al (2018) Evaluating shared decision making for lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med 178(10):1311–1316. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3054

Shen J, Crothers K, Kross EK, Petersen K, Melzer AC, Triplette M (2021) Provision of smoking cessation resources in the context of in-person shared decision making for lung cancer screening. Chest. Published online. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.016

Eberth JM, McDonnell KK, Sercy E et al (2018) A national survey of primary care physicians: perceptions and practices of low-dose CT lung cancer screening. Prev Med Rep 11(January):93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.05.013

McDonnell KK, Estrada RD, Dievendorf AC et al (2019) Lung cancer screening: practice guidelines and insurance coverage are not enough. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 31(1):33–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000096

Melzer AC, Golden SE, Ono SS, Datta S, Crothers K, Slatore CG (2020) What exactly is shared decision-making? A qualitative study of shared decision-making in lung cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med 35(2):546–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05516-3

Zeliadt SB, Hoffman RM, Birkby G et al (2018) Challenges implementing lung cancer screening in federally qualified health centers. Am J Prev Med 54(4):568–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.001

Kanodra N, Pope C, Halbert C, Silvestri G, Rice L, Tanner N (2016) Primary care provider and patient perspectives on lung cancer screening. A qualitative study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 13(11):1977–1982

Wiener RS, Koppelman E, Bolton R et al (2018) Patient and clinician perspectives on shared decision-making in early adopting lung cancer screening programs: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 33(7):1035–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4350-9

Slatore C (2019) COUNTERPOINT: can shared decision-making of physicians and patients improve outcomes in lung cancer screening? No. Chest 156(1):15–17

Hoffman RM, Reuland DS, Volk RJ (2021) The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services requirement for shared decision-making for lung cancer screening. JAMA 325(10):933–934. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1102873

Lowenstein LM, Richards VF, Leal VB et al (2016) A brief measure of smokers’ knowledge of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography. Prev Med Rep 4:351–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.07.008

Elwyn G, Hutchings H, Edwards A et al (2005) The OPTION scale: measuring the extent that clinicians involve patients in decision-making tasks. Health Expect 8(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00311.x

Carter-Harris L, Slaven JE, Monohan P, Rawl SM (2017) Development and psychometric evaluation of the lung cancer screening health belief scales. Cancer Nurs 40(3):237–244. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000386

Fukunaga MI, Halligan K, Kodela J et al (2020) Tools to promote shared decision-making in lung cancer screening using low-dose CT scanning: a systematic review. Chest 158(6):2646–2657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.610

Khairy M, Duong DK, Shariff-Marco S et al (2018) An analysis of lung cancer screening beliefs and practice patterns for community providers compared to academic providers. Cancer Control 25(1):1–8

Hoffman RM, Sussman AL, Getrich CM et al (2015) Attitudes and beliefs of primary care providers in New Mexico about lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography. Prev Chronic Dis 9(12):E108

Kanodra NM, Pope C, Halbert CH et al (2016) Primary care provider and patient perspectives on lung cancer screening. A qualitative study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 13(11):1977–1982

Melzer AC, Golden SE, Ono SS, et al (2020) "We just never have enough time": clinician views of lung cancer screening processes and implementation. Ann Am Thorac Soc 17(10):1264-1272. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-262OC

Coughlin JM, Zang Y, Terranella S et al (2020) Understanding barriers to lung cancer screening in primary care. J Thorac Dis 12(5):2536–2544

Lewis JA, Petty WJ, Tooze JA et al (2015) Low-dose CT lung cancer screening practices and attitudes among primary care providers at an academic medical center. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24(4):664–670

Ersek JL, Eberth JM, McDonnell KK et al (2016) Knowledge of, attitudes toward, and use of low-dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening among family physicians. Cancer 122(15):2324–2331. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29944

Henderson LM, Benefield TS, Bearden SC et al (2019) Changes in physician knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding lung cancer screening. Ann Am Thorac Soc 16(8):1065–1069. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-867RL

Triplette M, Kross EK, Mann BA et al (2018) An assessment of primary care and pulmonary provider perspectives on lung cancer screening. Ann Am Thorac Soc 15(1):69–75. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201705-392OC

Rajupet S, Doshi D, Wisnivesky JP et al (2017) Attitudes about lung cancer screening: primary care providers versus specialists. Clin Lung Cancer 18(6):e417–e423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2017.05.003

Raju S, Khawaja A, Han X, Wang X, Mazzone PJ (2020) Lung cancer screening: characteristics of nonparticipants and potential screening barriers. Clin Lung Cancer 21(5):e329–e336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2019.11.016

Roth JA, Carter-Harris L, Brandzel S et al (2018) A qualitative study exploring patient motivations for screening for lung cancer. PLoS ONE 13(7):e0196758. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196758

Bellinger C, Pinsky P, Foley K, Case D, Dharod A, Miller D (2019) Lung cancer screening benefits and harms stratified by patient risk: information to improve patient decision aids. Ann Am Thorac Soc 16(4):512–514. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201810-690RL

Pinsky PF, Bellinger CR, Miller DP Jr (2018) False-positive screens and lung cancer risk in the National Lung Screening Trial: implications for shared decision-making. J Med Screen 25(2):110–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969141317727771

Lowenstein LM, Godoy MCB, Erasmus JJ et al (2020) Implementing decision coaching for lung cancer screening in the low-dose computed tomography setting. JCO Oncol Pract 16(8):e703–e725. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00453

Studts JL, Thurer RJ, Brinker K, Lillie SE, Byrne MM (2020) Brief education and a conjoint valuation survey may reduce decisional conflict regarding lung cancer screening. MDM Policy Pract 5(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2381468319891452

Tammemägi MC, Katki HA, Hocking WG et al (2013) Selection criteria for lung-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 368(8):728–736. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1211776

Lau YK, Bhattarai H, Caverly TJ et al (2021) Lung cancer screening knowledge, perceptions, and decision making among African Americans in Detroit, Michigan. Am J Prev Med 60(1):e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.07.004

Caverly TJ, Hayward RA (2020) Dealing with the lack of time for detailed shared decision-making in primary care: everyday shared decision-making. J Gen Intern Med 35(10):3045–3049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06043-2

Caverly TJ, Cao P, Hayward RA, Meza R (2019) Identifying patients for whom lung cancer screening is preference-sensitive: a microsimulation study. Physiol Behav 176(3):139–148. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-2561

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ms. Erica Sercy for her editorial guidance and edits.

Funding

This study was funded through an institutional grant from the University of South Carolina Office of the Vice President for Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All members of the research team contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. In addition, authors contributed to study conceptualization (AZ, JME, DM), data curation (SP, SW, AZ), formal analysis (AZ), methodology (AZ, JME, DM), funding acquisition (JME), project administration (JME, DM), supervision (JME, DM), visualization (AZ), and original draft writing (JME, AZ, DM).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study was approved under expedited review (45 CFR 46 — categories #5 and #7) by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of South Carolina and of Wake Forest University.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Previous Abstract Presentation

Selected components of this research were presented at the North Carolina Chapter of the American College of Physician Annual Meeting (February 2021).

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 33.4 KB)

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eberth, J.M., Zgodic, A., Pelland, S.C. et al. Outcomes of Shared Decision-Making for Low-Dose Screening for Lung Cancer in an Academic Medical Center. J Canc Educ 38, 522–537 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-022-02148-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-022-02148-w