Abstract

Numeracy is highly relevant for therapy safety and effective self-management. Worse numeracy leads to poor health outcome. Most medical information is expressed in numbers. Considering the complexity of decisions, more information on the patient’s ability to understand information is needed. We used a standardized questionnaire. Content was self-perception of numeracy, preferences regarding decision-making with respect to medical issues, and preferred content of information from four possible answers on side effect of cancer therapies (insomnia) within two scenarios. Overall, 301 participants answered the questionnaire. Presentation of facts in numbers was rated as helpful or very helpful (59.4%). Higher numeracy was associated with higher appreciation for presentation in numbers (p = 0.002). Although participants indicated presentation of facts in numbers as helpful in general, the favored answer in two concrete scenarios was verbal and descriptive instead of numerical. Numeracy is highly relevant for therapy safety and effective self-management. Health professionals need more knowledge about patient’s ability and preferences with respect to presentation of health information. An individualized patient communication might be the best strategy to discuss treatment plans. We need to understand in which situations patients benefit from numerical presentation and how managing numerical data might influence decision processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health literacy is closely linked to literacy and entails people’s knowledge, motivation, and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information [1]. Health literacy is needed to make decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention, and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during life course [1]. It is known that a low level of health literacy has negative consequences for health status [2,3,4]. For this reason, improving health literacy is a major concern of the German national cancer plan and similar initiatives in other western countries. A fundamental part is to ensure access to group-oriented and quality-assured information. The overall goal is to strengthen shared decision-making [5].

Shared decision-making focuses on patient-physician-communication. In daily patient care, this means that physicians have to communicate more mindfully and should adapt their verbal and written communications to the needs of each person [6,7,8].

Much information used for decision-making is presented in numbers. The ability to understand and work with numbers is described as numeracy [9]. In order to decide, at least two different scenarios and their consequences have to be compared. Most frequently, scenarios are characterized by numbers, rates, and relations described in numbers. In oncology, comparing two treatment options includes a set of numbers describing different endpoints as survival (progression free and overall survival) or different short- and long-term side effects. For each individual patient, these endpoints have a different weighing according to individual preferences. Besides, any procedure in oncology is highly complex and has usually far-reaching consequences. In addition, cancer patients report that with the emotional burden of the diagnosis, the capability to concentrate on a topic and to understand any information decreases [10]. Accordingly, a target group oriented risk presentation and communication essential.

Considering the complexity of decisions and their importance for the patient’s future, more information on the patient’s ability to understand information is needed. In particular, understanding how numbers are perceived and how this influences decision-making is important [11]. Accordingly, we decided to conduct a survey among German cancer patients comprising numeracy and preferences regarding decision-making with respect to medical issues in two concrete scenarios.

Methods and Participants

This survey was an anonymous survey using a standardized questionnaire.

Participants

We asked participants of two big German conferences for cancer patients and their relatives in 2015 and 2016. These conferences were organized by the German Cancer Aid and the German Cancer Society at Jena and Berlin. The conferences offer a broad range of diverse information for different types of cancer.

Questionnaire

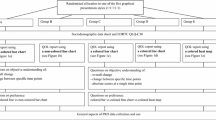

We designed a questionnaire by including items from already validated questionnaires and integrating new items.

The questionnaire consisted of four parts:

- 1.

Demographic data (patient or caregiver, age, gender, education, type of cancer, year of first diagnosis)

- 2.

Self-perception of numeracy (subjective numeracy scale, short form, based on a 6-point Likert scale) [12]

- 3.

Preferences regarding decision-making with respect to medical issues (control preferences scale) [13,14,15]

- 4.

The design of the forth part is based on our former work on ethical preferences of patients from which we learnt that a concise situation helps patients to name their preferences [16]. We chose a side effect of cancer therapies (sleep disturbances) with two scenarios (1: information on the occurrence, 2: information on supportive treatment). We asked the participants to choose the preferred content of information by the physician from four possible answers ranging from mere information of occurrence to detailed information regarding cause and frequency (see also Table 2).

Demographic data were queried via a selection list. Each item for self-perception of numeracy and preferences regarding decision-making was rated on a 6-point Likert scale, values were added, and the mean was calculated.

Ethical Vote

According to the rules of the ethics committee at the University Hospital of the J.W. Goethe University at Frankfurt/Main, due to anonymity, no ethical vote was necessary.

Statistics

IBM SPSS Statistics 24 was used for data collection, analysis of frequencies, and associations using chi-squares test and bivariate analyses; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic Data

All in all, 301 participants answered the questionnaire, 180 at Jena and 121 at Berlin (see Table 1). More than half of the participants were patients (114 in treatment and 85 after treatment (37.9% and 28.2% respectively)). More than 90% of the participants were older than 40 years; two thirds were older than 60 years. Nearly two thirds of patients were female (60.5%). Most patients had breast cancer (28.2%) or prostate cancer (13.0%).

Self-Perception of Numeracy

On a 6-point Likert scale, most participants rated their ability to do fractions as very good to good (67.0%) (Fig. 1).

Accordingly, presentation of facts in numbers was rated as helpful or very helpful by 59.4% of the participants (Fig. 2). Higher numeracy was associated with higher appreciation for presentation in numbers (p = 0.002).

Female participants rated their numeracy lower than males (p = 0.014). Yet, with respect to preferences on data presentation, there was no gender specific difference. There was no association between age and preferences for numbers. But higher education was significantly associated with high self-perception of numeracy (p < 0.001) and preferring data presentation by numbers (p = 0.006).

Decision-Making

One hundred thirty participants preferred shared decision-making (43.2%). Another 125 participants (41.5%) preferred to decide by themselves and only 45 participants (15.0%) preferred the physician to decide for them.

Patients and relatives at the conference at Berlin declared to make decisions by themselves significantly more often (p < 0.001). Older participants (> 71 years) reported preferring to make decisions by themselves more often (p = 0.041). In contrast, education and self-rated numeracy did not show any correlation.

Information Preferences

Considering information on insomnia (scenario A), most participants (127, 42.2%) preferred detailed information without numbers or the same information with numbers (97, 32.2%) (see Table 2). The answers considering information about supportive therapy for insomnia (scenario B) revealed other preferences. In this scenario, an answer with a clear recommendation was the preferred one (“Best we start with cognitive behavior therapy. In case this does not work, I’ll prescribe you a drug.” 36.2%). Detailed information with or without concrete numbers would be preferred by 18.9% or 22.3% respectively. There was no association between age, education or self-rated numeracy, and information preference. Those participants indicating that they liked numerical presentations chose number-based information significantly more often (p = 0.028) in scenario A.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to combine information on patients’ numeracy, preferences in presentation of information with statistical data, and decision-making.

Over the past three decades from 1980 to 2007, the number of patients who prefer to participate in decisions is increasing [17]. About two thirds of patients with advanced cancer prefer active or shared decisional control [18,19,20]. Accordingly, more than 40% of participants in this study wanted a shared decision. Yet, another 40% of participants wanted their own decision without any involvement of a physician. These findings are in line with a meta-analysis among 3491 patient with cancer [14]. Yet, some authors report much lower numbers for those preferring an active role. Singh and colleagues calculated that half of the patients would like a shared decision of physician and patient, 26% would like to play an active role and 25% want to take a passive role at decision [14]. One explanation could be the distribution of cancer entities in our survey because more than 40% of participants had breast cancer or prostate cancer. Active decision-making is more common among patients with these two cancer entities than other types of cancers [21].

Only a minority of participants in our study (15.0%) prefer a passive role leaving treatment decisions to their doctor. This number is comparable to various reviews in which also the fewest patients prefer paternalism [17, 22, 23].

The majority of the participants in our survey assessed their ability to understand and work with numbers as very good to good. Galesic and colleagues in 2011 were able to show that patients with low numeracy more often prefer to delegate the decision to the physician [24]. In contrast, we did not find any association between preferred decision model and self-rated numeracy. One explanation might be that our data are based on self-rating which might differ from real numeracy to some degree.

With respect to the concrete situation, in most cases, presentation of facts in numbers was evaluated as helpful.

Although participants indicated presentation of facts in numbers as helpful in general, the favored answer in the first scenario was verbal and descriptive instead of numerical. Only by those participants disclosing a high affinity towards numerical presentation number-based information was rated as useful.

In the second scenario considering information on supportive therapy in case of insomnia, the preferred answer was a short treatment strategy without numbers and without outline of different options thus excluding decision. In this scenario, we did not find an association between preference of numerical presentations and choice of number-based information. Why the meaning of detailed information with numbers differs in both scenarios is not clear. While we offered information about insomnia in the first scenario, we clarified about treatment options in the second scenario. One hypothesis might be that for information, numbers convey more clarity and simplicity. In case of treatment, numbers, especially statistical numbers of success and risk rates, enhance complexity while a simple treatment strategy is easy to comprehend.

Another problem is an imbalance between the need for medical information and complexity of requested information. As our data show, concrete information preferences do not differ much with respect to education or numeracy. As a consequence, programs to enhance patients’ health literacy cannot overcome this information barrier alone.

A similar discrepancy arises between the preferred decision role of participants and preferred information presentation especially in scenario B. In fact, a systematic review found many studies using the Control Preference Scale revealing a gap between peoples’ preferences and their actual involvement [21]. Role preference in decision-making may also change over time and differs between different types of cancers [25]. Frequently, patients expressed greater preference for involvement than was currently the case [26]. One reason might be that physicians do not offer space for participation or that patients in case of a decision refrain from participating. One main reason for the former is trust in competence of the physician [27]. Reasons for the latter might be that they do not feel competent or that they try to avoid responsibility or simply that they perceive too much emotion to make a decision.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, a selection bias is possible. The interviews were conducted at cancer congresses. Thus, a preselection could have taken place in favor of medically educated or higher educated lay people. As well, we only have reached people in good general condition and not those suffering from advanced cancer or acute side effects of oncological treatment. Also we did not analyze the point of time concerning the medical history of cancer. Similarly, we did not consider to cultural specific differences [28] or to psychological adjustment characteristics [29]. Furthermore, we have collected subjective and not objective numeracy. These data could be different, which could lead to a different interpretation of our findings.

Moreover, the chosen scenarios are not representative of physician-patient communication. In fact, they represent rather simple information sets. The simplicity on the other hand most probably makes patients answering more precisely to the questions.

Conclusion

Literacy and numeracy are strongly correlated but are not the same. There are still a lot of patients with adequate reading ability and nevertheless poor numeracy skills [9, 30] and vice versa. Numeracy is a multidimensional skill and many health-related tasks rely on numeracy. Numeracy is highly relevant for therapy safety and effective self-management. Worse numeracy results in an increased risk for poor health outcome. Numeracy may be an explanatory factor for adverse outcomes beyond the explanations provided by overall literacy [30].

Number representation depends on many factors such as context and patient characteristics. As a result, it is difficult to derive clear recommendations for providers of patient information. We need to understand in which situations patient prefer and benefit from numerical presentation and how managing numerical data might influence decision processes. Moreover, we have to explore, which variables influence decisional role preference and how detailed information is needed for which target group and for which type of information. According to our results, information should be processed verbally and descriptively for patients with low numeracy. Patients with high numeracy should get a numerical presentation of number-based information. However, in order to be able to make definitive statements, in-depth knowledge is lacking. More studies are needed to understand the complex nature of decision-making in health care. Furthermore, studies are needed focusing on impact of personal and contextual factors including setting, disease, numeracy, and educational level.

References

Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J et al (2012) Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 12:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

World Health Organization (2013) Health literacy: the solid facts. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen

Sørensen K, Pelikan JM, Röthlin F, Ganahl K, Slonska Z, Doyle G, Fullam J, Kondilis B, Agrafiotis D, Uiters E, Falcon M, Mensing M, Tchamov K, Broucke S, Brand H (2015) Health literacy in Europe: comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur J Pub Health 25:1053–1058. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv043

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K (2011) Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 155:97–107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (2012) Nationaler Krebsplan - Handlungsfelder, Ziele und Umsetzungsempfehlungen [National Cancer Plan - fields of action, objectives and implementation of recommendations]. Druckerei im Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, Berlin

Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group (2017) Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD001431. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5

Trevena LJ, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Edwards A et al (2013) Presenting quantitative information about decision outcomes: a risk communication primer for patient decision aid developers. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 13 Suppl 2:S7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S7

Spiegle G, Al-Sukhni E, Schmocker S et al (2013) Patient decision aids for cancer treatment. Cancer 119:189–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27641

Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, Davis D, Gregory R, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Elasy TA (2006) Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med 31:391–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.025

Keinki C, Seilacher E, Ebel M, Ruetters D, Kessler I, Stellamanns J, Rudolph I, Huebner J (2016) Information needs of cancer patients and perception of impact of the disease, of self-efficacy, and locus of control. J Cancer Educ 31:610–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0860-x

Wegwarth O, Gigerenzer G (2018) The barrier to informed choice in cancer screening: statistical illiteracy in physicians and patients. Recent Results Cancer Res 210:207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64310-6_13

McNaughton CD, Cavanaugh KL, Kripalani S et al (2015) Validation of a short, 3-item version of the subjective numeracy scale. Med Decis Making 35:932–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X15581800

Henrikson NB, Davison BJ, Berry DL (2011) Measuring decisional control preferences in men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 29:606–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2011.615383

Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ et al (2010) Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the control preferences scale. Am J Manag Care 16:688–696

Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P (1997) The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res 29:21–43

Bartholomäus M, Zomorodbakhsch B, Micke O, et al Cancer patients’ needs for virtues and physicians’ characteristics in physician- patient-communication - a survey among patient representatives. Submitted

Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G (2012) Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 86:9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004

Shields CG, Morrow GR, Griggs J, Mallinger J, Roscoe J, Wade JL, Dakhil SR, Fitch TR (2004) Decision-making role preferences of patients receiving adjuvant cancer treatment: a university of Rochester cancer center community clinical oncology program. Support Cancer Ther 1:119–126. https://doi.org/10.3816/SCT.2004.n.005

Hubbard G, Kidd L, Donaghy E (2008) Preferences for involvement in treatment decision making of patients with cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs 12:299–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2008.03.004

Tricou C, Yennu S, Ruer M, et al (2017) Decisional control preferences of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care. Palliat Support Care 1–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951517000803

Tariman JD, Berry DL, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp K (2010) Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 21:1145–1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp534

Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R (2006) Patients’ preference for involvement in medical decision making: a narrative review. Patient Educ Couns 60:102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.003

Gaston CM, Mitchell G (2005) Information giving and decision-making in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 61:2252–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.015

Galesic M, Garcia-Retamero R (2011) Do low-numeracy people avoid shared decision making? Health Psychol 30:336–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022723

Butow PN, Maclean M, Dunn SM, Tattersall MHN, Boyer MJ (1997) The dynamics of change: cancer patients’ preferences for information, involvement and support. Ann Oncol 8:857–863

Vogel BA, Bengel J, Helmes AW (2008) Information and decision making: patients’ needs and experiences in the course of breast cancer treatment. Patient Educ Couns 71:79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.023

Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Tong C (2011) Information that affects patients’ treatment choices for early stage prostate cancer: a review. Can J Urol 18:5998–6006

Yennu S, Rodrigues LF, Shamieh OM, Tricou C, Filbet M, Naing K, Ramaswamy A, Perez-Cruz PE, Bautista MJS, Bunge S, Muckaden MA, Sewram V, Fakrooden S, Noguera Tejedor A, Rao SS, Williams JL, Cantu H, Hui D, Reddy SK, Bruera E (2016) A multicenter study of patients decisional control preferences in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:6578–6578. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.6578

Colley A, Halpern J, Paul S, Micco G, Lahiff M, Wright F, Levine JD, Mastick J, Hammer MJ, Miaskowski C, Dunn LB (2017) Factors associated with oncology patients’ involvement in shared decision making during chemotherapy. Psychooncology 26:1972–1979. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4284

Rothman RL, Montori VM, Cherrington A, Pignone MP (2008) Perspective: the role of numeracy in health care. J Health Commun 13:583–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730802281791

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zomorodbakhsch, B., Keinki, C., Seilacher, E. et al. Cancer Patients Numeracy and Preferences for Information Presentation—a Survey Among German Cancer Patients. J Canc Educ 35, 22–27 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1435-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1435-4