Abstract

Black women in the USA have both a higher percentage of late-stage diagnoses as well as the highest rates of mortality from breast cancer when compared to women of other ethnic subgroups. Additionally, Black women have the second highest prevalence of cervical cancer. Many reports evaluating the cancer outcomes of Black women combine data on African-born immigrants and US-born Blacks. This categorization ignores subtle yet important cultural differences between the two groups, which may ultimately affect breast and cervical cancer screening practices. Therefore, this study investigated knowledge and awareness levels of breast and cervical cancer screening practices among female African-born immigrants to the USA residing in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area. Data were collected from 38 participants through key informant interviews, focus group sessions, and a sociodemographic questionnaire over a 3-month study period. Results suggest that fatalism, stigma, and privacy are among the major factors that affect the decision to seek preventative screening measures for breast and cervical cancer among this population. Additionally, the study implies that cervical cancer awareness is significantly lower among this population when compared to breast cancer. This study highlights differences between women of African descent residing in the USA and the need for continued research to increase understanding of the manner in which immigrant status affects health-seeking behavior. This information is critical for researchers, physicians, and public health educators aiming to design culturally appropriate interventions to effectively reduce the prevalence of breast and cervical cancer among female African immigrants living in the USA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

African–American women in the USA have higher rates of mortality [1] and a higher percentage of late-stage diagnoses of breast and cervical cancer when compared to white, Hispanic–Latino, American Indian, and Asian women [1–4]. Moreover, in comparison to these same ethnic subgroups, African–American women also have the second highest incidence [1] and highest mortality rate from cervical cancer [1]. In light of these disparities, concentrated evaluations of factors that reduce breast and cervical cancer screening are necessary to create effective programs that work to decrease the cancer burden experienced by African–American women.

Confounding this evaluation is that many reports of breast and cervical cancer data categorize African-born immigrants to the USA along with American-born Blacks [4]. This categorization ignores subtle yet significant cultural differences between the two groups that may have widespread effects on health outcomes [4]. In recent years, the USA has experienced a significant increase in the number of African immigrants residing within its borders [5]. The 2000 census estimated that 881,300 individuals residing in the USA were African-born immigrants [5]. By 2010, this number had reached 1,607,000 individuals [6]. With this rapid increase in African-born immigrants residing in the USA, it is imperative to develop successful outreach methods to provide more cancer screening among this group in order to increase early detection and treatment.

Research suggests that many differences exist between the cancer screening practices of American women and women who immigrated to the USA [7]. A survey administered in 2000 by the National Health Institute showed that women who had immigrated to the USA within the past 10 years were less likely to have had a Pap test and mammogram than any other US population group, including uninsured citizens [7]. Furthermore, previous literature has also asserted that among immigrants, age and language acculturation are significant predictors of self-perceived health status [8]. These differences in beliefs and practices further indicate that categorizing African-born immigrants to the USA along with American-born Blacks presents a skewed perspective of the data.

The limited research evaluating the cancer screening practices specifically of female African immigrants has suggested that access, cultural factors, spiritual beliefs, and familial influences are among the determining factors of knowledge and attitudes of African women who immigrate to the USA [9]. However, further research into this area is needed in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of the unique factors that affect this population. Therefore, this study was completed with the intention of supplementing the minimal available information regarding the breast and cervical cancer outcomes of African-born immigrants to the USA. Information to this regard is critical to developing applicable programs to effectively reduce the incidence and mortality from breast and cervical cancer among this population.

The Washington D.C. metropolitan area boasts one of the largest populations of African immigrants in the USA; with an estimated population of 114,000, Black African immigrants constitute 11 % of the total immigrant population in the area [10]. This high concentration of African immigrants makes it an ideal location to evaluate the unique situation of breast and cervical cancer of African immigrant women. Specifically, this study aimed to investigate the knowledge, perceived barriers, and frequency of breast and cervical cancer screening among African immigrant women residing within the Washington D.C. metropolitan area. Furthermore, this study aimed to determine the effects of cultural factors, spiritual beliefs, and familiar influences on breast and cervical cancer screening and to assess whether these beliefs vary with age.

Methods

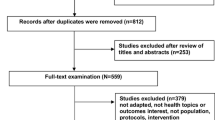

Participants

After receiving approval from the University of Michigan’s Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited through churches, community events such as fairs and picnics, and word of mouth. The study team approached approximately 60 community members to describe the study. Individuals who showed interest in participating were given further information and contacted later by the study team to schedule a focus group session.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) suggests that beginning in their 20s, women should have clinical breast examinations performed approximately every 3 years and that women should begin Pap tests no later than at 21 years of age [11]. The ACS also asserts that women 65 and over who have had at least three consecutive negative Pap tests and no abnormal Pap tests in the past 10 years may choose to stop having pap smears [11]. Consequently, participants were female, English-speaking, African immigrants ranging from 20 to 70 years of age.

Study Design and Setting

Data for this study were gathered from May 2012 to August 2012. Information was collected through the use of sociodemographic questionnaires, focus group sessions, and key informant interviews. Focus groups are discussions among four to ten individuals in which a moderator leads the discussion around a particular topic and encourages each participant to answer questions [12]. Additionally, focus groups utilize the group dynamics and allow participants to deeply explore topics together and provide a more comprehensive view of the selected topic [13, 14]. Key informant interviews are conducted with selected community members who are particularly knowledgeable about the research question as it pertains to the target population [15]. This method of data collection is useful in providing researchers with additional in-depth insight into the research topic and a more thorough understanding of the environment of the target population [16].

Prior to partaking in the study, participants signed informed consent forms. The sociodemographic questionnaire was then administered to collect demographic information and assess general baseline knowledge regarding cancer screening practices. Following completion of the questionnaire, focus groups and key informant interviews were then utilized to gain more in depth insight of participants’ beliefs and perceived barriers to engaging in breast and cervical cancer screening practices.

Focus Groups

In order to assess generational differences in knowledge and attitudes towards breast and cervical cancer screening, the focus groups were constructed by age. The younger groups ranged from 20 to 39, while the older groups ranged from 40 to 70 years of age. Focus groups were primarily held on weekends in the homes of willing participants as well as in churches following Sunday service. The focus group protocol assessed the varying cultural factors, spiritual beliefs, and familial influences that may play a role in the amount and quality of cancer screening care obtained. Sessions ranged from 45 to 60 min long, and at the completion, participants were compensated with $10 Giant Grocery gift cards. Six focus groups were held with a total of 35 participants.

Key Informant Interviews

In addition to focus group sessions, this study incorporated key informant interviews. Selected key informants had strong administrative affiliations with the African Women’s Cancer Awareness Association, a local community-based organization, as well as Georgetown’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. Additionally, the informants were selected due to their extensive previous experience engaging within the community on matters of breast and cervical cancer screening. The study held one-on-one interviews with three key informants prior to holding the focus group sessions. The number of interviews was determined by the availability of staff and affiliates. The key informants also completed the sociodemographic questionnaire, and the interviews ranged from 45 to 60 min.

Results

Analysis

Information collected in the focus groups and key informant interviews was audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Two coders from the research team then independently analyzed the transcripts. During analysis, the coders developed themes and evaluated the patterns that emerged. Due to the lack of available literature pertaining to African immigrant women and breast and cervical cancer screening, the research team employed studies performed among African–American women to guide their analysis. Existing literature suggests that fear, fatalism, and perceived benefits and barriers affect adherence to cancer screening among African–American women [17–19]. Additionally, lack of knowledge, low perceived risk, and health care cost are other factors that have been cited as contributing to reduced rates of cancer screening among African–American women [20–22]. After analyzing the transcripts separately, the coders discussed identified themes and came to a consensus. Information from the key informant interviews, focus group transcripts, and questionnaires was then triangulated and assessed for similarities and differences.

Demographics

The study included a total of 38 participants across the three key informant interviews and six focus groups. Fourteen participants fell within the 20–39-year-old age range while 24 women fell within the 40–70-year-old age range. Participants were from Ghana and other West African countries including Cameroon, Nigeria, Zambia, and the Ivory Coast (Table 1). All participants self-identified as Christian. Sixty-eight percent of the participants were insured, while 16 % were uninsured and 16 % of participants declined to answer. A majority of the participants were full-time employees, and many were either 4-year or graduate degree holders. Lastly, the majority of participants reported an annual household income of between $40,000 and $74,999. This sample is closely representative of the demographics of the African immigrant population residing in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area. Ethiopians are the most prevalent African immigrant population in the area, followed by several West African countries including Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Cameroon, and Liberia, respectively [10]. Additionally, the 2005 American Community Survey suggested that 42 % of African immigrants residing within the area had obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher, and the median annual household income of the population was $53,000 [10].

Key Informant Interviews

The key informant interviews highlighted areas for concentration during focus groups. Key informants suggested that age, education level, and insurance status were largely influential factors in determining where women obtained information on breast and cervical cancer. Informants suggested that younger and more educated women tend to obtain information from the Internet. Women with insurance were more likely to receive screening reminders and other information from their primary care provider.

The informants acknowledged an increased awareness regarding breast cancer among the population; however, they also highlighted the fact that the area still has room for improvement, as one noted, “…[women] are talking about [breast cancer] but they’re not comfortable talking about it. There’s a difference when you talk about something with confidence and… when you talk about something with a whisper.” Key informants indicated a difference in awareness levels regarding breast cancer in comparison to awareness regarding cervical cancer. Also, informants cited privacy, lack of transportation, and other priorities such as work, school, or familial commitments taking precedence over obtaining screening. Additionally, the negative effects of culture and religion on screening practices were alluded to during the interviews. Informants discussed experiences with women who described cancer as a curse and chose to avoid screening because of the belief that their religion would protect them. Furthermore, informants had interacted with women who did not receive screening because their spouse did not consent to the procedure, or they themselves did not feel comfortable exposing themselves as would be needed for the screening process. Data collected from the key informant interviews were used to guide the focus group discussions.

Focus Groups

Increased awareness was a prominent motivating factor for participants. Many women with insurance credited the routine reminders from their primary care provider, while other women stated that one cancer death or multiple cancer deaths in the community increased their awareness and motivated them to receive screening (Table 2). For some women, experiencing a cancer screen firsthand served as a motivating factor to continue routine screening. Previously, these women avoided screening because of negative reports they had heard from friends and/or family members saying that screening was a painful process. Another theme that emerged as a motivator was experiencing a complication, such as a lump in the breast or vaginal pain, that led women to obtain a screen.

Countering the increases in awareness that motivated women to get screened, lack of awareness was a recurring reason many women cited for not receiving screening. This was particularly prevalent in regard to cervical cancer, where there was agreement across all focus groups that although breast cancer was gaining awareness, awareness of cervical cancer lags far behind. One participant commented, “People don’t know what cervical is,” implying that it is difficult to persuade women to receive screening for something they do not understand. Participants also discussed that symptoms of cervical cancer are frequently confused with or assumed to be menstrual symptoms, presenting another barrier to obtaining the proper treatment. Participants also discussed the difficulty of convincing community members to visit a physician for preventative measures, as the prevalent belief within the community is that physician visits should be reserved for when symptoms are present.

Fear was a concept that surfaced often within the focus group sessions as well as the key informant interviews. Women mentioned both the fear of pain during screening and the fear of receiving a cancer diagnosis as reasons for avoiding screening. Participants in several groups stated, “What you don’t know won’t hurt you,” in reference to avoiding cancer screening. The concept of fatalism also surfaced as women discussed the belief that a diagnosis of cancer would inevitably result in death.

Several religious and cultural factors were also cited as barriers to cancer screening. Women commented that it was not unlikely to hear the sentiment that a person’s faith would serve as a protection from cancer, with several women referencing the common use of the saying, “It is not my portion.” This saying is often used within the community to convey the belief held by many that once they have accepted God into their lives, He would protect their health and protect them from the development of cancer. Another sentiment that surfaced during the focus group sessions and interviews was the idea that cancer is perceived as a curse and therefore is often accompanied by stigma, shame, and the underlying belief that a woman must have done something bad to deserve a cancer diagnosis.

The issue of privacy was another common theme throughout the sessions. Privacy was discussed in reference to both the physical and social realm of many participants. Physical privacy was discussed in terms of the physical exposure required during a breast and/or cervical cancer screening—particularly with a male physician. Concepts surrounding social privacy stemmed from the factors of stigma and shame mentioned above. Participants stated that due to the stigma, women in the community who did have cancer were reluctant to divulge their cancer diagnosis. Additionally, one woman described a fear that if a mother with daughters was diagnosed with cancer and the information spread through the community, then her daughters may then become stigmatized as well. For the younger group of women (20–39), the issue of social privacy also extended to the process of obtaining cancer screening because of the close-knit nature of the African immigrant community. One woman detailed that after her most recent Pap smear, a family friend saw the participant leave the hospital and contacted her aunt, who then reported the information to the participant’s mother. By the time the participant reached home, her mother was waiting to question her regarding her hospital visit. She went on to assert that following this experience, she received medical attention at a hospital 45 min away from her residence to ensure that she could avoid similar encounters.

Transportation and costs were also barriers discussed in the focus groups. Many women stated that they themselves or women they knew who were interested in receiving screening simply did not have the means to attend an appointment. Additionally, women who lacked insurance cover cited the cost of screening as a barrier.

Challenges

The most challenging aspect of the study was the recruitment process. Often, when recruiting participants at community events, the mere mention of the word cancer resulted in negative reactions. Reactions to recruitment efforts exemplify the stigma associated with cancer and the challenges posed by outreach within this population.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that African-born immigrants to the USA experience similar motivators and barriers to obtaining cancer screening as American-born Blacks such as fear, fatalism, and lack of knowledge. However, there are also unique cultural and religious beliefs particular to the African immigrant population. For example, the concept of cancer being a curse and the need to obtain spousal consent and/or approval in order to receive screening were unique themes that emerged during the study.

Future Program Design

Both key informants and focus group participants suggested that an increase in community outreach efforts could help to both increase awareness and reduce feelings of fatalism. Specifically, women suggested that speaking for 5–10 min at regularly scheduled community events like picnics or parties would provide a large captive audience to disseminate pertinent information. Additionally, participants suggested that the use of cancer survivors in these outreach efforts would address the barrier of fatalism by showing women that “… cervical cancer or breast cancer is not a passport to your grave.” Many felt that seeing a person of similar ethnic decent who had survived their battle with cancer would encourage women to receive screening.

Additionally, participants also suggested that programs use patient navigators to assist women who were diagnosed with breast cancer in adhering to the prescribed treatment plan. Moreover, patient navigators could play a role in bridging any potential language gaps between patient and provider.

Key informants acknowledged the efforts being made to produce cancer education materials in African languages; however, they emphasized that more work in this area is needed in order to accommodate the growing African immigrant population. This suggestion was made in reference to both linguistically appropriate materials for the varying African language as well as the consideration of more subtle cultural nuances. For example, one participant encouraged that those who work to increase rates of cancer screening should be well versed in Biblical scripture in order to effectively respond to those who cite their faith as a reason why screening is not necessary. The participant elaborated that those working in the community should be able to respond to such comments by citing scriptures that encourage individuals to care for the body that God has given them.

Expanding upon this idea, participants stressed the importance of emphasizing to African women that faith and medicine are not mutually exclusive elements. Women stated that it was not uncommon for women within the community who have received a diagnosis of cancer to choose prayer as a method of treatment rather than receive medical treatment. Participants suggested that cancer outreach programs should involve churches and if possible empower religious leaders within the community to become advocates of cancer screening and treatment. These leaders can then emphasize to their congregation that prayer and medical treatment should be combined to yield the best result.

Limitations and Significance

This was a small focused study with a small sample size and a limited number of participants’ countries of origin. As a result, these results may be regionally specific and may only pertain to women who originate from West African countries. Additionally, the requirement for English-speaking participants and the study’s small sample size may limit its generalizability to the greater population. Despite these limitations, this study is significant as it begins to shed light on the cancer outcomes specifically of female African immigrants to the USA. Furthermore, this study begins to evaluate the manner in which immigration status affects access to health care. Moreover, this study highlights the effectiveness of utilizing qualitative methods and collaborating with community organizations to improve health outcomes within this population. Information gathered from this study should be utilized to inform effective interventions as well as more tailored health programs.

References

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds) (2013) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2010, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission posted to the SEER web site. Accessed 14 March 2013

Newman LA (2005) Breast cancer in African–American women. Oncologist 10(1):1–14

Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, Singh GK, Cardinez C, Ghafoor A, Thun M (2004) Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 54(2):78–93

Borrell LN, Castor D, Conway FP, Terry MB (2006) Influence of nativity status on breast cancer risk among US Black women. J Urban Health 83(2):211–220

U.S. Census Bureau (2002) Census 2000 special tabulations STP-159. http://www.census.gov/population/cen2000/stp-159/STP-159-africa.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2013

U.S. Census Bureau (2010) American community survey, 2010. http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/acs-19.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2013

Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC (2003) Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer 97(6):1528–1540

Ivanov LL, Hu J, Leak A (2010) Immigrant women’s cancer screening behaviors. J Community Health Nurs 27(1):32–45

Sheppard VB, Christopher J, Nwabukwu I (2010) Breaking the silence barrier: opportunities to address breast cancer in African-born women. J Nat Med Assoc 102(6):461–468

Kent MM, Wilson JH (2007) Immigration and America’s Black population. Population Bulletin 62(4):13, http://www.prb.org/pdf07/62.4immigration.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2013

American Cancer Society (2013) Cancer prevention and early detection facts and figures. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-037535.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2013

Liamputtong P, Ezzy D (2005) Qualitative research methods, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Melbourne

Krueger RA, Casey MA (2000) Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Morgan DL (1988) Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage, Newbury Park

Gilchrist VJ, Williams RL (1999) Key informant interviews. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL (eds) Doing qualitative research, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Sherry ST, Marlow A (1999) Getting the lay of the land on health: a guide for using interviews to gather information (key informant interviews). The Access Project. http://www.accessproject.org/downloads/final%20document.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2013

Wagle AM, Champion VL, Russell KM, Rawl SM (2009) Development of the Wagle health-specific religiousness scale. Cancer Nurs 32(5):418–425

Champion VL, Springston JK, Zollinger TW, Saywell RM, Monahan PO, Zhao Q, Russell KM (2006) Comparison of three interventions to increase mammography screening in low income African American women. Cancer Detect Prev 30:235–244

Champion VL, Skinner CS (2003) Differences in perceptions of risk, benefits, and barriers by stage of mammography and adoption. J Women’s Health 12(3):277–286

Gullatte M (2006) The influence of spirituality and religiosity on breast cancer screening delay in African American women: application of the Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior (TRA/TPB). The ABNF Journal 17(2):89–94

Nosarti C, Crayford T, Roberst JV, Elias E, McKenzie K, David AS (2000) Delay in presentation of symptomatic referrals to a breast cancer clinic: patient and system factors. Br J Cancer 82(3):742–748

Phillips JM, Cohen MZ, Moses G (1999) Breast cancer screening and African American women: fear, fatalism, and silence. Oncol Nurs Forum 26(3):561–571

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Ify Nwabukwu and the members of the African Women’s Cancer Awareness Association (AWCAA) for their assistance in the completion of this study. Ezinne Ndukwe was supported by the Cancer Epidemiology Education in Special Populations (CEESP) Program of the University of Nebraska (grant R25 CA112383).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ndukwe, E.G., Williams, K.P. & Sheppard, V. Knowledge and Perspectives of Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Among Female African Immigrants in the Washington D.C. Metropolitan Area. J Canc Educ 28, 748–754 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0521-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0521-x