Abstract

Introduction

Individual differences in attachment differentially predict dating motivations and behaviors among heterosexual individuals. Remarkably, little research has examined such topics in men who have sex with men (MSM).

Methods

In a sample of 118 MSM, we examined whether individual differences in attachment were differentially associated with motivations for using Grindr, a widely used geosocial networking application (GSNA) among MSM, and whether these motivations, in turn, predicted problematic Grindr use and depression. Data were collected in 2019.

Results

Attachment anxiety was associated with use of Grindr for self-esteem enhancement; this motivation, in turn, predicted more problematic Grindr use and higher depression. Attachment anxiety was also associated with problematic Grindr use via use of Grindr for companionship purposes. Those higher in attachment avoidance reported using Grindr for escapism and due to the ease of communication it affords; these motivations, in turn, were associated with greater problematic Grindr use. There were also indirect effects of attachment avoidance on symptoms of depression via escapism.

Policy Implications

Results suggest that attachment insecurity is associated with maladaptive motivations for GSNA use, and these motivations may place MSM at greater risk for depression and problematic GSNA use. Implications for social policy and professional practice are discussed, including the importance of clinicians assessing for problematic patterns of GSNA use and the need for practitioner training to include a focus on the unique predictors of mental health and well-being among gender and sexual minorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Geosocial networking applications (GSNAs) allow users to connect with other nearby users based on their proximity, and their use has increased rapidly over the past decade among heterosexual individuals and sexual minorities (e.g., Beymer et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2012; Sevi et al., 2018). Although people often use GSNAs to find potential sexual or romantic partners, recent evidence reveals wide ranging motivations for using GSNAs (Goedel and Duncan, 2015; Sumter et al., 2017). For instance, Sumter and colleagues (2017) found six key motivations for using Tinder, namely casual sex, love, self-worth validation, thrill or excitement, trendiness of using Tinder, and the ease of communicating online rather than in person. Recent evidence indicates that among heterosexual individuals, there are distinct sub-groups of Tinder users, with two sub-groups classified as “regulated” and two classified as “unregulated” (Rochat et al., 2019). These sub-groups differed on motivations for using Tinder, use patterns and problematic or compulsive use of Tinder; they also differed on indices of psychological adjustment, such as depressed mood (Rochat et al., 2019). Problematic use of GSNAs and other forms of technology is characterized by excessive use of GSNAs (e.g. more than a person intended to use), difficulty controlling use of GSNAs, use of GSNAs to avoid or escape negative emotions, and use that creates distress and functional impairment in various life domains (Griffiths, 2005; Marino et al., 2018; Orosz et al., 2018; Rochat et al., 2019).

Research investigating GSNA use and dating and casual sex more broadly, among men who have sex with men (MSM), is significantly lacking relative to literature on heterosexual adults (see Watson et al., 2017). Goedel and Duncan (2015) found that, among MSM, some used GSNAs to find a partner, date, or casual sexual partner, though a substantial proportion also used Grindr, a widely used GSNA used largely by gay men, to “kill time when bored” or to “make friends.” However, to our knowledge, no research has examined individual difference predictors of motivations for dating app use among MSM, and whether these motivations, in turn, predict problematic app use and psychological adjustment. Attachment theory, one of the most widely used theoretical frameworks for understanding adult romantic relationships, may provide a useful framework for addressing such questions (Mohr and Jackson, 2016).

Attachment is an emotional bond formed between an infant and caregiver that has implications for emotion regulation and relationships across the lifespan (Bowlby, 1969; Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016). Adult attachment is generally conceptualized along two dimensions: anxiety and avoidance. Attachment anxiety is characterized by heightened fear of abandonment and rejection in romantic relationships and significant concern about potential unavailability of attachment figures (Fraley et al., 2000). Attachment avoidance refers to discomfort with emotional closeness and intimacy in relationships, as well as excessive self-reliance (Fraley et al., 2000). Those who are low in both attachment anxiety and avoidance are said to have a secure attachment style.

Much evidence highlights that attachment security is associated with more satisfying and stable romantic relationships, whereas attachment insecurity (anxiety or avoidance) predicts wide ranging cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes that undermine relationship formation and maintenance (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016; Pepping et al., 2018b). Recent evidence suggests that attachment orientations are associated with the use of GSNAs among heterosexual individuals (Chin et al., 2019; Rochat et al., 2019). In a largely heterosexual sample, Chin and colleagues (2019) found that those high in attachment avoidance were less likely to use GSNAs, whereas those higher in attachment anxiety were more likely to use these apps. Attachment anxiety was associated with using GSNAs with the intention to meet people, whereas attachment avoidance was negatively associated with use of GSNAs to meet people.

Given that there are differences in motivations and patterns of use of GSNAs between heterosexual individuals and MSM (Licoppe, 2020), it is important to examine whether attachment orientations predict motivations for using GSNAs among MSM, and whether these motivations, in turn, are associated with indices of well-being and problematic GSNA use. Problematic app use has been conceptualized similarly to a behavioral addiction, encompassing excessive and compulsive use, mood modification, difficulty controlling app use, and continued use of the app despite distress and functional consequences (e.g., Orosz et al., 2018). Grindr, released in 2009, was the first GSNA specifically tailored to MSM and is the most widely used app among MSM, having approximately 27 million users in 2017 (Dating Site Reviews, 2020). Thus, in the current study, we examined whether attachment insecurity was associated with less adaptive motivations for using Grindr, and whether these motivations, in turn, would predict problematic Grindr use and symptoms of depression.

Attachment anxiety is associated with an intense desire for intimacy, a negative self-image, and expectations that others will not reciprocate their desire for closeness (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016). We therefore predict that those high in attachment anxiety may use Grindr to (1) alleviate loneliness and seek intimacy and companionship and to (2) seek self-esteem enhancement from potential partners; these motivations, in turn, are likely to predict more problematic and compulsive use of Grindr, as well as heightened depression. Attachment avoidance is associated with a reluctance to get close to others, efforts to reduce emotional intimacy, and more avoidant styles of coping and emotion regulation (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016). We therefore predict that those high in attachment avoidance would use Grindr because of the (1) ease of communication online rather than face-to-face, and as it (2) provides an ‘escape’ from potential problems or worries; these maladaptive motivations, in turn, are likely to predict more problematic and compulsive use of Grindr, as well as heightened depression.

Method

Participants

Participants were 118 adult MSM (Mage = 33.62, SD = 12.67) who had used Grindr within the past 30 days. Most reported their sexual orientation as gay (N = 90; 76.3%) or bisexual (N = 21; 17.8%), and 7 (5.9%) reported other sexual orientations. The majority of participants were Caucasian (N = 84; 71.2%), 13 were Hispanic/Latino (11%), and the remaining participants reported other backgrounds. Participants were recruited from both Australia and the USA via paid Facebook advertising.

Materials

Attachment. The Experiences in Close Relationships Revised (ECR)-Short Form (Wei et al., 2007) is a 12-item measure of attachment anxiety (e.g., “I need a lot of reassurance that I am loved by my partner”) and avoidance (e.g., “I try to avoid getting too close to my partner”). The measure is reliable and valid and correlates with long-form versions of the ECR (Wei et al., 2007). Internal consistency was high in the present study for avoidance (α = 0.80) and anxiety (α = 0.78).

Motivations for Grindr Use. The Tinder Motivation Scale is a 46-item measure that assesses motivations for use of dating apps (Sumter et al., 2017). Here, we used two of the subscales: ease of communication (e.g., “I feel less shy online than offline”) and self-esteem enhancement (e.g., “To feel better about myself”). Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each item reflected their motivation for using Grindr (as opposed to Tinder). Internal consistency was high for both the ease of communication (α = 0.82) and self-esteem enhancement (α = 0.92) motives.

We used two subscales of the Facebook Motivation Scale (Smock et al., 2011), namely escapism (e.g., “So I can forget about school, work, or other things”) and companionship (e.g., “So I won’t have to be alone”). Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each item reflected their motivation for using Grindr (as opposed to Facebook). Internal consistency was high for escapism (α = 0.84) and companionship (α = 0.88).

Problematic Grindr Use. We used an adapted version of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS; Satici and Uysal, 2015) to assess problematic Grindr use. The BFAS consists of 18 items that assess behavioral addiction to Facebook. Participants indicate how often in the past year they had experienced various symptoms. Example items include “spent more time on Facebook than initially intended”, “ignored your partner, family members, or friends because of Facebook”, “tried to cut down on the use of Facebook without success”, “felt bad if you, for different reasons, could not log on to Facebook for some time”, and “used Facebook so much that it had a negative impact on your job / studies.” We replaced “Facebook” with “Grindr,” but did not otherwise modify the items. Internal consistency was high (α = 0.93).

Depression. We used the depression subscale of the 21-item Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995; e.g., “I felt down-hearted and blue”). The DASS-21 is widely used and psychometrically valid and reliable (Henry and Crawford, 2005). Cronbach’s α was 0.92.

Procedure

The study received ethics approval from the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee. Participants were recruited via paid Facebook advertising. Upon clicking the advertisement, participants were directed to the Qualtrics platform where they could provide consent and complete a survey containing the measures listed above, and some additional items unrelated to the current study. Participants were able to enter a prize draw to win one of five $50 Amazon gift cards.

Analytic Plan. Means, standard deviations, and correlations were obtained for all study variables. To test the indirect effect of attachment insecurity (independent variable) on problematic Grindr use and depression (dependent variables) via motivations for Grindr use (mediators), we used the Process Macro with 10,000 bootstrap samples (Preacher and Hayes, 2004). This approach provides regression coefficients for the individual paths between the independent variables, mediators, and dependent variables and yields confidence intervals for estimates of the indirect effects using bootstrapping, a resampling method that resamples multiple smaller samples, with replacement, from the original sample (Hayes, 2017).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations are presented in Table 1. Attachment anxiety and avoidance were each associated with maladaptive motivations for Grindr use, and each of the motivations with greater problematic Grindr use and depression.

Attachment anxiety was positively associated with use of Grindr for self-esteem enhancement (B = 0.46, p < 0.001) and for companionship (B = 0.44, p < 0.001). Self-esteem enhancement (B = 0.14, p = 0.018) and companionship (B = 0.30, p < 0.001) motivations were each associated with more problematic Grindr use. Self-esteem enhancement (B = 1.19, p = 0.043) was associated with greater depression, though companionship (B = 0.30, p = 0.605) motivations were not. As can be seen in Table 2, the total effect of attachment anxiety on problematic Grindr use and depression were each significant. Attachment anxiety was also indirectly associated with more problematic Grindr use via self-esteem enhancement and companionship motivations and with greater depression via self-esteem enhancement motivations only.

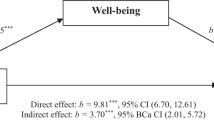

Attachment avoidance was positively associated with use of Grindr due to the ease of communication (B = 0.29, p < 0.001) and for escapism (B = 0.30, p < 0.001). Ease of communication (B = 0.21, p = 0.002) and escapism (B = 0.29, p < 0.001) motivations were each associated with more problematic Grindr use. Escapism (B = 1.23, p = 0.025) was associated with depression, though ease of communication was not (B = 1.11, p = 0.074). As displayed in Table 3, the total effect of attachment avoidance on problematic Grindr use and depression were each significant. Attachment avoidance was also indirectly associated with more problematic Grindr use via ease of communication and escapism motivations and with greater depression via escapism motivations only.

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to examine whether individual differences in attachment were differentially associated with motivations for Grindr use and whether these motivations, in turn, predicted problematic Grindr use and depression. Results were generally consistent with predictions. Attachment anxiety was associated with more problematic Grindr use via self-esteem enhancement and companionship motivations and with greater depression via self-esteem enhancement motivations. Attachment avoidance was associated with problematic Grindr use via ease of communication and escapism motivations, and with greater depression via escapism motivations. There were also direct effects of attachment anxiety and avoidance on depression, but not problematic Grindr use, once the motivations were controlled for.

The finding that attachment anxiety was associated with use of Grindr for self-esteem enhancement is consistent with evidence that those high in attachment anxiety tend to have self-worth that is contingent on gaining approval from others (e.g., Cheng and Kwan, 2008). Those high in attachment anxiety also reported use of Grindr to seek companionship, or to avoid being alone, which is in line with substantial evidence that anxious individuals readily seek out intimacy and closeness, but are often dissatisfied with the quality of these relationships (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016). Both motivations were, in turn, associated with more problematic Grindr use, characterized by excessive use and detrimental effects of compulsive overuse on areas of their lives; this finding adds to existing literature demonstrating that anxious attachment is associated with social media addiction (Blackwell et al., 2017). Attachment anxiety was associated with greater depression via self-esteem enhancement motivation, which is in line with evidence that anxious individuals are prone to excessive reassurance-seeking in relationships (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016).

Attachment avoidance was associated with problematic Grindr use via ease of communication and escapism motivations. Much evidence suggests that attachment avoidance predicts efforts to maintain emotional distance from others (Guerrero, 1996) and greater use of avoidant coping and emotion regulation strategies (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016). The present findings suggest that avoidant individuals use Grindr because it is a potentially less demanding method of interacting with others, relative to face-to-face interactions, and may provide a form of ‘escape’. These maladaptive avoidance-based motivations were associated with problematic Grindr use, which is also consistent with prior research demonstrating links between attachment avoidance and various forms of addictive behavior (e.g., Blackwell et al., 2017). Attachment avoidance was associated with greater depression via use of Grindr for escapism, which builds on a large body of evidence showing that the avoidance-based emotion regulation strategies associated with attachment avoidance undermine psychological well-being (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016).

The present results are broadly consistent with prior research examining the influence of attachment on dating behaviors and motivations and GSNA use among heterosexual adults (e.g., Chin et al., 2019; Rochat et al., 2019). The current study extends on prior research by examining the influence of attachment orientations on motivations for GSNA use and the associated effects on well-being and problematic use of GSNAs, among MSM. Recent research suggests that attachment insecurity may undermine the formation and maintenance of long-term romantic relationships, leading some people to remain involuntarily single (Pepping et al., 2018a, b; Pepping and MacDonald, 2019). In light of the results of the current study, future research should examine whether maladaptive motivations for using GSNAs might also be one pathway by which attachment insecurity undermines the formation and maintenance of romantic relationships.

Results of the present research have important implications for social policy and practice. Specifically, results suggest that maladaptive motivations for using Grindr are associated with problematic Grindr use and depression. These findings highlight the importance of therapists, counselors, and other practitioners working with MSM assessing how clients use GSNAs and the potential impact on their mental health and well-being. Where indicated, practitioners should consider whether assisting clients to recognize and reduce potentially unhelpful patterns of GNSA use might be warranted. In addition, policies relating to the education and training of practitioners who work with gender and sexual minorities (e.g., Pepping et al., 2018a) should include a focus on unique predictors of mental health and well-being among MSM, including the role of unhelpful patterns of GNSA use.

There are some limitations to acknowledge. The cross-sectional nature of the current study means that conclusions about causation cannot be made. For instance, it is possible that those who are more depressed might be motivated to use Grindr for self-esteem enhancement. Longitudinal research is needed to track Grindr use patterns, motivations for using Grindr, and mental health outcomes over time in order to assess temporal precedence. In addition, recruitment via targeted Facebook advertising means that we may not have reached some individuals who were not ‘out’, and the extent to which the current sample is reflective of all Grindr users or MSM is unclear. In addition, factors such as internalized stigma could contribute to perceptions of some aspects of problematic Grindr use, and future research should examine the potential association between internalized stigma and problematic GSNA use among MSM. Finally, to reduce variability, we assessed only Grindr users in the current study given it is the largest GSNA for MSM; however, we cannot assume that the results of the current study generalize to users of other apps, nor can we assume that the results of the current study are specific to Grindr per se. The current results may or may not generalize to users of other GSNAs, and indeed more broadly to other forms of social media. Future research is needed to examine whether attachment prospectively predicts a wider range of motivations for using multiple GSNA apps among MSM, as well as online technology use more broadly. In addition, it is plausible that motivations for Grindr use differ based on age, level of outness, and relationship status, and future research with larger samples should examine these factors as potential moderators. Future research should also examine potential psychosocial outcomes of problematic GNSA use, such as anxiety, depression, relationship distress, and general well-being. In summary, results clearly suggest that individual differences in attachment are differentially related to motivations for using Grindr and that maladaptive motivations for Grindr use, in turn, predict more problematic Grindr use and depression.

References

Beymer, M. R., Weiss, R. E., Bolan, R. K., Rudy, E. T., Bourque, L. B., Rodriguez, J. P., & Morisky, D. E. (2014). Sex on demand: Geosocial networking phone apps and risk of sexually transmitted infections among a cross-sectional sample of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles County. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 90, 567–572. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2013-051494.

Blackwell, D., Leaman, C., Tramposch, R., Osborne, C., & Liss, M. (2017). Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss: New York: Basic Books.

Cheng, S. T., & Kwan, K. W. (2008). Attachment dimensions and contingencies of self-worth: The moderating role of culture. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(6), 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.003.

Chin, K., Edelstein, R. S., & Vernon, P. A. (2019). Attached to dating apps: Attachment orientations and preferences for dating apps. Mobile Media & Communication, 7, 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157918770696.

Dating Site Reviews (2020). Retrieved from: https://www.datingsitesreviews.com/staticpages/index.php?page=grindr-statistics-facts-history.

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350.

Goedel, W. C., & Duncan, D. T. (2015). Geosocial-networking app usage patterns of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: Survey among users of Grindr, a mobile dating app. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 1(e4), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.

Griffiths, M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Guerrero, L. K. (1996). Attachment-style differences in intimacy and involvement: A test of the four-category model. Communications Monographs, 63(4), 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759609376395.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York, New York: Guilford.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657.

Licoppe, C. (2020). Liquidity and attachment in the mobile hookup culture. A comparative study of contrasted interactional patterns in the main uses of Grindr and Tinder. Journal of Cultural Economy, 13, 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2019.1607530.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U.

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2018). A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 83, 262–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.009.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press.

Mohr, J. J., & Jackson, S. D. (2016). Same-sex romantic attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), The Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications (3rd ed., pp. 484–506). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Orosz, G., Benyo, M., Berkes, B., Nikoletti, E., Gál, É., Tóth-Király, I., & Bőthe, B. (2018). The personality, motivational, and need-based background of problematic Tinder use. Journal of behavioral addictions, 7(2), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.21.

Pepping, C. A., Lyons, A., & Morris, E. M. (2018a). Affirmative LGBT psychotherapy: Outcomes of a therapist training protocol. Psychotherapy, 55(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000149.

Pepping, C. A., MacDonald, G., & Davis, P. J. (2018b). Toward a psychology of singlehood: An attachment-theory perspective on long-term singlehood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(5), 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417752106.

Pepping, C. A., & MacDonald, G. (2019). Adult attachment and long-term singlehood. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 105–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.006.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553.

Rice, E., Holloway, I., Winetrobe, H., Rhoades, H., Barman-Adhikari, A., Gibbs, J., Dunlap, S. (2012). Sex risk among young men who have sex with men who use grindr, a smartphone geosocial networking application . Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 1(S4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6113.S4-005.

Rochat, L., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Aboujaoude, E., & Khazaal, Y. (2019). The psychology of “swiping”: A cluster analysis of the mobile dating app Tinder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8, 804–813. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.58.

Satici, S. A., & Uysal, R. (2015). Well-being and problematic Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 185–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.005.

Sevi, B., Aral, T., & Eskenazi, T. (2018). Exploring the hook-up app: Low sexual disgust and high sociosexuality predict motivation to use Tinder for casual sex. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 17–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.053.

Smock, A. D., Ellison, N. B., Lampe, C., & Wohn, D. Y. (2011). Facebook as a toolkit: A uses and gratification approach to unbundling feature use. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 2322-2329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.07.011

Sumter, S. R., Vandenbosch, L., & Ligtenberg, L. (2017). Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telematics and Informatics, 34, 67–78.

Watson, R. J., Snapp, S., & Wang, S. (2017). What we know and where we go from here: A review of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth hookup literature. Sex Roles, 77(11–12), 801–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0831-2.

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701268041.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jayawardena, E., Pepping, C.A., Lyons, A. et al. Geosocial Networking Application Use in Men Who Have Sex with Men: The Role of Adult Attachment. Sex Res Soc Policy 19, 85–90 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00526-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00526-x