Abstract

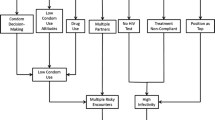

Between 2006 and 2008, detailed interviews were conducted with 138 men with a median age of 24 years (ranging from 16 to 39) from seven Anglophone Caribbean countries and one territory: Anguilla, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. The interviews investigated prevalent construction(s) of masculinity in the region, with particular attention to transitions from childhood to manhood, boys’ education, risk-taking, health, violence, and crime. This paper examines the relationship between masculinity and risk. Far from being considered antisocial and to be avoided, risk-taking serves to define youthful masculinity and is sought out and experienced as a rite of passage. Having multiple female sexual partners is a hallmark of a “real man” and not being considered a “real man” is shameful—potentially fatal in homophobic settings. Paradoxically, by stigmatizing “insufficient” sexual interest in women and valorizing the quest for multiple female partners, homophobia acts as a potent driver of heterosexual risk. While risk was definitive of masculinity, safety was not. Avoiding a reputation for “sexual failure” often takes precedence over the threat of pregnancy or catching a sexually transmissible infection. On the contrary, pregnancy confirms manhood and sexual potency—even when it is unwanted. The research found that safety directly challenges the obligations of manhood and this may explain why HIV control has been so difficult. Condoms are foregone if there is a risk of appearing sexually inexperienced or of losing an erection, especially if details of this “failure” might leak out. Likewise, abstinence and sticking to one partner are incompatible with virile masculinity and displaying insufficient heterosexual interest can imply homosexuality and provoke homophobic consequences. All forms of sexual safety as they are currently framed—condoms, partner reduction, and abstinence—implicitly challenge masculine norms and all convey notions of emasculation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (STI) are widespread in the Caribbean and although infection rates vary widely island by island, the prevalence of HIV in some countries ranks among the world’s highest (UNAIDS 2010). While prevalence is high, studies have shown that awareness of, and knowledge about, HIV prevention are also high (Ogunnaike-Cooke et al. 2007). On the other hand, the survey data reveal a well-recognized paradox: that there is a substantial gap between near universal HIV awareness among young people, including high levels of prevention knowledge, and the generally low levels of precautions that are taken. This gap between knowledge and practice has previously been referred to as the ‘KAP Gap’ (see Plummer 2009). Closing this gap is one of the chief aims of HIV/STI prevention initiatives. Recognizing that this gap exists is the basis of the present research, the aim of which is to understand this gap better. Elsewhere, we have argued that sexual risks are “socially embedded” and that this social embedding helps to explain why the KAP gap exists and why it is so resistant to change (Plummer 2009). The present paper will explore “social embedding” further, particularly in relation to sexual risk and masculinity.

Gender in the Anglophone Caribbean has been the subject of a growing body research, especially in recent decades. Notable among the contributions is the work of the Institute for Gender in Development Studies at the University of the West Indies (for more, see Reddock (2004)). The Institute (formerly Centre), its collaborators and associates have undertaken important research into the shifting gender arrangements in the Caribbean. For example, the Anglophone Caribbean has seen large shifts in the gender balance in education (Chevannes 1999:11; Reddock 2004:xv; Figueroa 2004:141–143). This has been a consistent trend over many years. Enrolments at the largest university in the Anglophone Caribbean, the University of the West Indies (UWI) are a case in point. The UWI has major semi-autonomous campuses in each of the independent countries of Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago and each of these countries has experienced a consistent and sustained decline in the proportion of male enrolments: from a peak of 77 % in the 1949–1950 academic year to a low of 33 % during the years that the current study was undertaken (see Table 1 and Fig. 1 for details). The good news is that girls are doing well. The bad news is that the proportion of boys who complete a degree and who finish secondary school has dropped dramatically. At present, only a small minority of undergraduate enrolments in the University of the West Indies is male and there is no evidence that the drop in participation by young men is due to them being educated elsewhere. Similar findings have also been found in studies of secondary education in the region (Parry 2004; Reddock 2004). Of course, a growth in the number of boys who have not completed a degree, let alone their secondary education, will have profound social consequences if sustained in the long term.

The present work stems from prior research into masculinities in Australia by the present author (Plummer 1999). The approach draws heavily on several long standing social science traditions. Although not explicit in the research, the preoccupation with masculinity and its relationship with sexuality draws on a methodological interest in Freudian approaches to interviewing and analysis but is also influenced by Gale Rubin, whose work has focused on unpacking the relationships between sexuality and gender (see Rubin 2011:34). The complexities and symbolic significance of the passage from childhood to manhood is a central feature of the current research and this aspect rests on the bedrock of the classic work of Van Gennep (1960/1908), albeit with an acceptance of modern circumstances and of postmodern interpretations that seek multiple levels of meaning and recognize the importance of power and agency (Foucault 1990). The research found that taboo looms large in the passage from childhood to manhood and it is here that the work of anthropologists such as Gilmore (1990) and the classic monograph on stigma by Erving Goffman (1963) was to guide the reading and interpretation of the transcripts. Also influential was the approach taken by Mac an Ghaill (1994) and his approach to working with language, power, and masculinity, especially among young men during the school years. In addition to the important work by researchers in the Anglophone Caribbean mentioned below, the milestone work of Ramirez (1999) in Puerto Rico and of Richard Parker (see Parker 2009) in Brazil have assisted in contextualizing sexual and gender traditions in region in non-Anglophone cultural settings.

The present paper is one of several that have come from the Caribbean Masculinities Project (detailed in “Methods” below). The picture that has emerged from this project is that falling education levels for boys, levels of violence and crime, risk-taking, and poorer outcomes for men’s health are linked and that a central factor that links these developments is gender (in the guise of masculinity; Plummer, McLean & Simpson 2008). The present project is not alone in reaching this conclusion. In recent years, the findings of a number of prominent Caribbean researchers have contributed substantially to the picture (Bailey et al. 2002:8–9; Chevannes 1999:26; Crichlow 2004:206; Figueroa 2004:147; Parry 2004:176). This paper examines data on the relationship between masculinity and sexual risk in the Anglophone Caribbean. The evidence demonstrates that far from being considered antisocial and to be avoided, risk-taking serves to define youthful masculinity and is sought out and experienced as a rite of passage. These findings have important implications for social policy, particularly in relation to sexual health promotion, the quality of sexual relationships, sexual abuse and violence, and STI prevention.

Methods

Between 2006 and 2008, detailed interviews were conducted with 138 young men from seven Caribbean Anglophone countries and one British Caribbean territory as part of the Caribbean Masculinities Project. The project set out to document the formative experiences of Caribbean men during their transition from childhood to manhood: in the family, at school, in peer groups, on the street and beyond school. Interviews explored prevalent construction(s) of masculinity in the region, especially focusing on boys’ education, risk-taking, health, violence, and crime. A modified grounded theory approach was used based on the work of Glaser and Strauss (1967) with adaptations as discussed by Layder (1993). Interviews were conducted based on the procedures outlined by Kvale (1996). This approach also builds upon the methods used in prior studies by the present author, which examined masculinities in Australia (Plummer 1999). A total of 138 detailed interviews were conducted in seven Anglophone Caribbean countries and one territory: Anguilla, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. Purposive sampling was undertaken to identify participants who were in a position to provide concrete descriptions and informed insights into the social and cultural constructions of gender in the region. Data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach with the aim of generating better explanations for gender arrangements in the Caribbean and their relationship to risk-taking—particularly in the case of the present paper, to sexual risk taking. Measures were taken to ensure that the explanatory framework that emerged was detailed, meaningful and, wherever possible, relevant to society more generally. These measures included: adding cases until saturation occurred; including diverse, variant and negative cases; and relating the findings to the work of other researchers. Recruitment was undertaken with the assistance of key contacts in each country. Contacts were drawn from the University network (the University of the West Indies has campuses and study centers in all countries studied) as well as through sexual and reproductive rights organizations, HIV support groups, gay groups, and officials from education departments and the police. The result was a diverse sample encompassing race (principally mixed race, African and East Indian descent), socio-economic background (poor, working, middle, and upper middle class), geographic location (garrison/ghetto communities, rural and urban, multiple countries), religion (Catholic, Protestant, and Hindu), and academic background (early school leavers, school “completers”, and tertiary educated). For further participant details, see Table 2. It should be noted that while participants gave valuable accounts of their own experiences, they also acted as lay field observers. In doing so, they provided rich data on complex social systems that they interacted with and which encompass many additional participants (in the form of villages, communities, schools and peer groups). Using a strategic approach to sampling (known as theoretical sampling), the project assembled a detailed and highly relevant database that can be used to explore social trends, to interpret those trends, to draw conclusions about processes underlying change, and to formulate social policy recommendations.

Results

Negotiating the transition from childhood to manhood is a crucial achievement in a boy’s development (Gilmore 1990). During this period, boys consolidate their sexual identity, become fully sexually active, and earn the right to be called a man. It is not possible to make this transition without engaging with the (powerful) rules of gender—what for boys might best be called “compulsory masculinity”. In other words, in a myriad of subtle and quite unsubtle ways, crafting and projecting an acceptably gendered persona is essential. The present research was able to generate a comprehensive multicountry database from diverse sources concerning the ways in which gender styles and roles are learned and enforced in the Anglophone Caribbean.

A useful model that emerged from the data is that masculinity is governed by a dense web of obligations and taboos. The taboos of manhood largely revolve around repudiating characteristics that are considered childish, effeminate, soft, disloyal to the peer group, gay, or in some other socially-determined way, to lack masculinity. Here is an illustration describing popular Caribbean dancehall culture:

… they will use certain lyrics and you will have to respond by raising your hand. So that ways they will ask you if you love woman, put yuh two hands in the air and you will have to put up the two hands; if you want to ‘burn up chi-chi man’, you will put your hand as if it were around a lighter and you are lighting a fire; or they will say ‘shot the battiboy’ and you will have your hand shaped like a gun and moving it up and down as if you were shooting something in the air. So those were really used as a measuring stick, and if you didn’t do it then there will be confrontation and harassment after… so if you didn’t burn up chi-chi man: you are gay; if you didn’t put up your hands when they said if you love woman: then you are gay; if you didn’t light the fire: you are gay…

(Participant: SVG02; Country: Saint Vincent; Male; Age 21; Christian; working/middle class; mixed race; at least some secondary school)

Note that “chi-chi man”, “battiboy” (and later we will see the Guyanese word “antiman”) are local homophobic terms analogous to “faggot” in other countries (Allsopp 1996). A “chi chi” is a Jamaican creole term for termite and is also used as a derogatory term for being gay. According to the study participants, the term entered popular culture through Jamaican dancehall music drawing on the analogy between termites chewing on wood and sucking an erect penis also being referred to as “wood”. The term “batti” in battiboy and battiman is a reference to “bottoms” and by extension to the homosexual use of the male bottom and especially to being the receptive partner during intercourse. While the various homophobic terms have their countries of origin (in the case of chi-chi and battiman, from Jamaica), popular culture ensures that they are generally understood throughout the Anglophone Caribbean.

In contrast to the taboos, the obligations of manhood form the other half of this binary: physical development, strength, aggressiveness, bravado, suppressing “soft” emotions, risk-taking, and sexual conquest are all viewed as archetypes of “true” masculinity.

… the boys… talked about the girls and you were forced to prove your macho-ness by going with this girl. You will go to parties and you will have to pick up a particular girl and you had to sleep with her because you didn’t have a choice.

(Participant: SVG02; Country: Saint Vincent; Male; Age 21; Christian; working/middle class; mixed race; at least some secondary school)

Importantly, in combination, the taboos against softness and the valorization of hard masculinity combine to generate pressure towards hypermasculine “acting out”.

… many guys they go out of the way to be hyper-masculine, do all these things and start misbehaving, breaking all of these rules, and all those things because at the hint of any suspicion [about sexuality].

(Participant: GUY09; Country: Guyana; Male; Age 23; Christian; middle class; African descent; at least some university)

This pressure can lead to deeply problematic outcomes for the men themselves and for society as a whole. Moreover, this combination has the capacity to inactivate “circuit breakers” against dangerous antisocial behavior: a boy who does not want to participate in risky peer group activities or who does not project sufficient (hyper)masculine credentials is at risk of being considered disloyal and soft. Gaining a reputation for either can be perilous. Disloyalty to the peer group/gang can be considered treasonous and “softness” in the Caribbean (and elsewhere) raises suspicions of homosexuality: both can lead to rejection, violence, and even death, particularly where homophobia runs deepest (most infamously in parts of Jamaica). The following quote illustrates the approach to a boy at school who broke ranks with the boys and played with girls:

Well they waited until you were with the girls and you playing them games they would just say; burn, roast, antiman, chi-chi man, you know they say ‘battiman fi dead’. ‘Look a girl’. Different things you used to hear them chanting. Meaning like, they would kill you.

(Participant: SKN08; Country: Saint Kitts; Male; Age 25; Christian; African descent; at least some secondary school)

Note that the phrase “battiman fi dead” translates as “gay man must die”, presumably by being burned as the associated words “burn” and “roast” suggest. The term antiman has a number of variations, sometimes being auntieman, sometimes pantyman and more often than not, antiman (literally the opposite of a “real” man). While relatively innocuous to foreign ears, the interviews reveal that antiman is considered deeply offensive in certain Caribbean countries (notably in Guyana) and designates an effeminate male, especially a male homosexual in a similar way that the term faggot does elsewhere (Allsopp 1996).

Earlier in this paper, the changing face of boys education was raised as an important issue from which a number of social problems flow. The present research sheds light on why this situation has arisen. In the past, intellectual prowess was a legitimate way for boys to assert their masculinity for all to see. However, educational opportunities are now rightly open to both sexes and boys appear to be seeking alternative ways to differentiate themselves and to establish their masculine credentials. In this respect, a key domain where boys continue to be able to assert their masculinity is through their biological differences from girls.

… you had to play sports, and be into sports… people didn’t see reading and things like that as being a hobby, a pastime or anything like that… You wouldn’t sit down and read a novel openly in school and many times you wouldn’t study in front of people because it wasn’t too cool to be seen studying… definitely peer pressure, although it might not be vocalized in so many words, but it was in the air, it was something nobody had to say, it was just in the air that, ‘OK, we have free time you should be more into sweating, build a sweat, build you muscles rather than enjoying a good novel or a good book’. That’s just a little too prissy and bright and girly and therefore suspect.

(Participant: TNT09; Country: Trinidad; Male; Age 28; Christian; African descent; at least some university)

This shift in emphasis from intellectual prowess—which is increasingly being stigmatized as “soft” and unmanly—towards physical prowess constitutes what I argue is a “retreat to the body” as a dominant means for differentiating modern masculinities.

… you never really associate cool with being smart. It was always something physical or some material possession… Expensive sneakers, latest football gears, the latest haircut. For us it was young men who has a beard.

(Participant: TNT09; Country: Trinidad; Male; Age 28; Christian; African descent; at least some university)

This growing emphasis on physical masculinity has implications for dress codes, grooming, physical development, sports, aggressiveness, violence, crime, and for that matter the collective power of gangs as a key social unit around which social forces can organize (Plummer and Geofroy 2010). The emphasis on physical prowess also manifests in an emphasis on what can be done with that prowess. In terms of appearance, the data is rich with evidence that previous baggy dress styles that defined youthful masculinity are shifting towards tighter clothing that emphasize physical characteristics including musculature and penis size. The body is being enhanced and displayed, for example with bling (the ostentatious use of jewelry and other fashion accessories), sports clothes, tattoos, and so on. And more than ever, feats of strength, bravado, and risk-taking have become definitive of the “real man”. In the words of Bailey and colleagues, “street influences were particularly telling in that transition period to adulthood… Many of the styles on the street were accentuated as the basis for securing what was imagined to be an adult masculine identity. The street was trouble, yet it was where a man was made” (Bailey et al. 1998:55).

The “retreat to the body” and to bodily performance has sexual ramifications. The heavy pressure on boys to conform to prevailing masculine standards (compulsory masculinity) includes pressures to demonstrate their masculinity through displays of sexual desirability and to prove themselves through sexual performance. Of course, ordinarily this expectation is unequivocally heterosexual and any deviation is risky (what Adrienne Rich (1980) referred to as “compulsory heterosexuality”).

… you weren’t supposed to have platonic friendships with the girls. Your interest in girls supposed to be strictly intimate. You’re interested in them because you want to have a girlfriend, have a relationship and then have sex with her. You’re not suppose to have platonic relationship with girls… that would be stuck on the not-so-cool list.

(Participant: GUY09; Country: Guyana; Male; Age 23; Christian; middle class; African descent; at least some university)

But powerful pressures extend beyond boys simply “being” heterosexual: when it comes to manhood, reputation is everything and to establish a reputation there must be both evidence and an audience to appreciate it.

Boys’ sexual escapades are performed as much for peer group approval and to enhance one’s status as they as they are for pleasure—indeed many accounts reveal that pleasure is secondary, or rather, that boys take greatest pleasure in what the episode does for their “reputation”.

… what you did, who you did it with, how long you did it for, positions. Boys with sex want every single detail. You had the opportunity to meet a girl and have any sexual encounter you know you had to have a conference after… Most of the girls at that age would tell you [whisper] ‘don’t tell anybody.’ And all the boys tell them ‘Baby, I look like that kinda man? I would never tell anybody!’ and as you finish and as you leave that girl, you go home on the phone and call every single friend and give them details.

(Participant: TNT09; Country: Trinidad; Male; Age 28; Christian; African descent; at least some university)

Furthermore, suggestions of sexual activity are interrogated by peers to confirm that accounts are authentic and conform to group (heterosexual) expectations.

I had my first sexual encounter at twelve years old and it’s because of the fact that you had to be man… you had to have sex to be a man and the worse part of that encounter was that I got hurt… but yet still I felt I was macho. Now even that added insult to injury when I went to tell them they wouldn’t believe me. When I told them I did it.

(Participant: SLU04; Country: St Lucia; Male; ; Age 39; Christian; working/middle class; African descent; at least some secondary school)

The data also revealed a taboo against sticking faithfully to one female sexual partner, which is taken to indicate a lack of virile masculinity. The Jamaicans have a special term for men who are faithful to one female partner: they are referred to as “one burners” (Bailey et al. 1998:66).

… if you’re in a grouping where all of your bredrin dem [peers are] promiscuous and them have different, different girl each night and you just have a one girl a hold on to, them going to start calling you a ‘one-burner’…

(Participant: JAM07; Country: Jamaica; Male; Age 22; Christian; working class; African descent; at least some university)

Being labeled a “one burner” raises questions about a man’s sexuality, namely, that he could be gay. In short, taking risks and having multiple female sexual partners is a hallmark of being a “real man” and not being considered a “real man” is shameful—and because of the homosexual connotations, potentially fatal.

The expectations of “compulsory heterosexuality” extend to gay men as well. The data contains numerous graphic examples of deep and at times violent homophobia. The following quotation is from a participant who experienced sustained homophobic abuse in his neighborhood, which culminated in him having acid thrown in his face. He was left with extensive permanent scarring.

I felt the liquid when I turned, and right away my mind said to me, acid. And at that time my hair was not in braids but it was in the funky dread, so I felt it, and right away I leaned and my mind said to me this is acid. So there I am leaning, looking on the ground, looking to see if pieces of flesh would have been dropping there. I went to the police station, I reported it again, they took me to the hospital. I was hospitalized I think for two months and a week thereabouts nursing my acid wounds.

(Participant: GUY13; Country: Guyana; Male; Age 29;Christian; working class; mixed race; at least some secondary school)

Coupled with expectations of “compulsory heterosexuality” and under considerable pressure from family and peers, the situation leads many men to get married both as a way of protecting themselves and sometimes accompanied by the questionable assumption that marriage might “cure” them.

I have two friends of mine who are gay, but they have decoys [girlfriends]…

(Participant: GRN02; Country: Grenada; Male; Age 23; Christian; middle class)

The result is a phenomenon known in popular culture as men living on the “down low”: unable to be openly gay but nevertheless driven by powerful homosexual desires, they end up having sex with men “on the side”. The data from the present research therefore throws an important paradox into sharp relief: by stigmatizing “insufficient” sexual interest in women by all men, by reinforcing the quest for multiple female partners, and by leaving little option for gay men apart from getting married, homophobia emerged as a potent driver of heterosexual risk for HIV and other STI.

To this point, we have established that risk-taking and sexual prowess are key aspects of defining manhood, and that establishing a masculine reputation is a crucial achievement of the transition from boyhood. The question that now arises is what about sexual safety? The data on this point is clear. There was consensus that abstinence was an unrealistic goal. Given the importance of forging a masculine identity and the penalties for failing to do so, it was considered much more important to present oneself as sexually experienced and that abstinence had the potential to raise questions about sexual preference and to be a threat to a male reputation.

… crucifixion… name callings, jokes, ridicules, because of what I stood for. I lost all my friends, I walked a lonely path… it was very lonely… I felt I was the only one not having sex. Everybody else was having sex.

(Participant: SLU04; Country: St Lucia; Male; Age 39; Christian; working/middle class; African descent; at least some secondary school)

Likewise, we have already seen evidence that even sticking to one female partner can be problematic, especially for younger males whose reputation is not yet secure. Like abstinence, sticking to one partner can attract critical attention from peers and the importance of securing a reputation can outweigh precautions against sexual risk.

Condoms too are problematic, especially when the atmosphere surrounding peer group culture is loaded with performance pressure.

I fear that I might not have an erection and I just… die and that’s not good for a man having sex with a woman to just die in sex… I mean before sex or even die during sex.

(Participant: SLU08; Country: St Lucia; Male; Age 30; Christian; working class; African descent; at least some secondary school)

While it was common for participants to report that they had rejected condoms because they reduced sexual pleasure, this concern with pleasure seems disproportionate given that condoms save lives. The accounts given by young men in this study shed light on this paradox. The combination of the need to maintain a masculine reputation, of performance pressure, of the sexual risks posed by inexperience, and of altered sensation all raise anxieties about sexual failure.

They not accustom to using [condoms]. It wasn’t really helping out their erection… it wasn’t hard. Some guys say that it use to desensitize them and then some people say they rather the feeling without condom.

(Participant: TNT05; Country: Trinidad; Male; Age 22; Christian; East Indian descent; at least some university)

Reputations can be won and lost depending on sexual conquest. Losing an erection while trying to use a condom poses a risk to the young man’s status not only with his female partner but also among his peers and the community if information about his “failure” leaks out or if he is subsequently exposed when interrogated by his peers.

Conclusions

Gender roles are socially constructed and over time they shift. The present research demonstrates these changes in a number of areas, most notably in boys’ education. The data presented here shows how gender is relational, that is, that movements in the roles of women necessarily entail shifts for men—I say “necessarily” because gender is a mutually exclusive binary where masculinity is by definition not femininity and vice versa. Improvements in girls’ education is an evolving success story in the Anglophone Caribbean, but the reversal of fortune in boys’ education is not. However, these developments should not be misconstrued as being the “fault” of girls. If the changes in modern gender arrangements are approached strategically, then there is no logical reason why boys and girls can’t both do well in school. On the other hand, the data suggests that boys are disinvesting in formal schooling in the search for alternative ways to define their masculinity and to maintain their dominance—by shifting the focus to forging their manhood in physical rather than intellectual terms. This shift has been responsible for what I call the “retreat to the body” and the “rise of hard masculinity”. That is to say that biological differences—tough bodies and physical dominance—offer a more certain way to define manhood as other paths to manhood become increasingly gender-neutral (or possibly even undergo reversals of their gender significance). These differences assume particular importance during the passage from childhood to manhood, the period that we now refer to as adolescence.

The retreat to physical masculinity is mirrored in sexual practice. A reputation for sexual prowess is a highly valued aspect of contemporary manhood. It is here that the obligations and taboos of manhood come into direct conflict with public health. One of the mantras of public health is to reduce or eliminate risk. Yet, the data shows that there are enormous pressures on young men to secure a masculine reputation and that physical performance and risk-taking are definitive of manhood. These findings have important implications for promoting sexual safety. While risk is definitive of masculinity, safety is not. Safety is functionally the opposite of risk, and safety in the form of abstinence, partner restriction, and/or condoms can all be read as challenging masculinity, that is to say, as being potentially emasculating and/or feminizing because they seek to restrain what men do sexually. We have already noted the consensus in the data that abstinence is contrary to what is generally held to be the destiny of men—to be sexually successful. In a similar way, men who are faithful to a single female partner also attract critical comment (“one burner”) and questions are raised about their virility and sexual preference.

In the case of condoms, it seems that the underlying fear associated with condoms is that using them might lead to a lost erection and sexual “failure”. Thus, condoms will be foregone if there is a risk of appearing inexperienced or of erectile failure, especially if details of this “failure” were to leak out. In the hot-house of male politics and the pecking order of peer groups, allegations of sexual failure can pose a grave threat to one’s reputation. Indeed, sexual failure, at its extreme, could be interpreted to mean that the person never really was all that interested in women. Such details could lead to “social death”; while in deeply homophobic communities the threat of death is real.

The final theme to emerge from the data is to explore how such dangerous and often antisocial practices remain so entrenched. In another paper, I introduced the term “social embedding” in an attempt to explain the resilience of risk taking (Plummer 2009). In short, “risk” featured in the current study as an integral element of gender: as a key marker for defining manhood. Arguably then, risk taking is entrenched because gender itself is entrenched: it is central to human social organization. But the story is more complicated. Surveillance, policing, and enforcement of gender roles are particularly intense during the transitional period from childhood to manhood. Chief among the arbiters and enforcers of the laws of manhood are peer groups, at school and on the streets (Bailey, Branche, McGarrity and Stuart 1998:55). We have already noted the multiple ways that homophobia works to reinforce heterosexual risk. Both successful masculinity and heterosexuality are “compulsory” and the punishments for failure can range from humiliation, rejection to assault, and death.

Two further points are important to note. First, there was considerable variation from place to place in the accounts that were provided. For example, there are a large number of words that were used in much the same way that words like “faggot” are used in other parts of the world. Likewise, individuals demonstrated great variation and agency in how they responded to these heavy social expectations and taboos concerning gender. Not all participants were “victims” and others showed remarkable resilience despite the odds. However, for the purposes of this paper, the aim was to draw out the common ground and general principles that were also apparent in the data. It will be the task of future papers and future research to look further into these latter issues.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

The present research raises a number of key challenges for public policy. The first is that gender, in this case masculinity, has deep ramifications for public health, particularly because the heavy taboos and obligations of manhood regularly contradict safety. The second challenge is that homophobic taboos underpin heterosexual risk through a number of important mechanisms; and third, that risk-taking is deeply socially embedded, especially by virtue of being enmeshed in contemporary gender arrangements. It is the contention of this paper that these three factors are significant contributors to the resilience of sexual risk and to sustaining the KAP gap and that they help to explain why HIV prevention has been so well understood but so difficult to achieve.

Given the conclusions reached above, the following policy recommendations and future directions should be considered: First, that gender analysis in public health and in development must take masculinity into account, both though more and better research and through systematic integration into planning and strategies. While there have been many excellent strategies to provide support for women and women’s reproductive rights, progress will always be severely restrained if they are accompanied by reactionary outcomes for men. Second, that more strategic approaches to incorporating masculinity are required if public health and other agencies are going to be effective. Rather than interventions that (unwittingly) run contrary to the norms and expectations of manhood, these norms and obligations should be leveraged for the benefit of health promotion and to strengthen outcomes and presumably make them more sustainable. In other words, to compete with the prevailing culture, sexual precautions need to be totally cool and incredibly hot at the same time! Third, that the norms and obligations of masculinity and femininity are constantly moving and that long sighted strategies are needed to “steer” these movements away from dangerous, antisocial, hypermasculine consequences. Fourth, that central to these shifting gender arrangements and to the resilience of risk-taking (and the “KAP Gap”) is the surveillance, policing and enforcement undertaken especially by peer groups (Plummer 2009). While peer education has long been recognized as a potentially powerful tool in health promotion, it is my opinion we have been far too unsophisticated and piecemeal in the ways we have attempted to leverage peer dynamics and youth culture—unlike the commercial world and the kids themselves, who are endlessly creative and effective!

References

Allsopp, R. (1996). Dictionary of Caribbean English usage. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press.

Bailey, W., Branche, C., & Henry-Lee, A. (2002). Gender, contest and conflict in the Caribbean. Mona, Jamaica: Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Bailey, W., Branche, C., McGarrity, G., & Stuart, S. (1998). Family and the quality of gender relations in the Caribbean. Mona, Jamaica: Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Chevannes, B. (1999). What we sow and what we reap—problems in the cultivation of male identity in Jamaica. Kingston, Jamaica: Grace Kennedy Foundation.

Crichlow, W. E. A. (2004). History, (Re)memory, testimony and biomythography: charting a buller Man’s Trinidadian past. In R. E. Reddock (Ed.), Interrogating Caribbean masculinities (pp. 185–222). Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press.

Figueroa, M. (2004). Male privileging and male academic under-performance in Jamaica. In R. E. Reddock (Ed.), Interrogating Caribbean masculinities. Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press.

Foucault, M. (1990). The history of sexuality (Vol. 1). New York: Vintage Books.

Gilmore, D. D. (1990). Manhood in the making. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity (1986th ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster.

Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. London: Sage.

Layder, D. (1993). New strategies in social research: an introduction and guide. London: Polity.

Mac an Ghaill, M. (1994). The making of men. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Ogunnaike-Cooke, S., Kabore, I., Bombereau, G., Espeut, D., O’Neil, C., & Hirnschall, G. (2007). Behavioural surveillance surveys (BSS) in six countries of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OESC) 2005–2006. Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO): Washington.

Parker, R. (2009). Bodies, pleasures and passions: sexual culture in contemporary Brazil (2nd ed.). Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Parry, O. (2004). Masculinities, myths and educational under-achievement: Jamaica, Barbados and St Vincent & the Grenadines. In R. E. Reddock (Ed.), Interrogating Caribbean masculinities. Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies.

Plummer, D. (1999). One of the boys: masculinity, homophobia and modern manhood. New York: Haworth.

Plummer, D. (2009). How risk and vulnerability become ‘socially embedded’: insights into the resilient gap between awareness and safety in HIV. In C. Barrow, M. de Bruin, & R. Carr (Eds.), Sexuality, social exclusion & human rights: vulnerability in the Caribbean context of HIV. Kingston: Randall.

Plummer D., & Geofroy S. (2010). When bad is cool: violence and crime as rites of passage to manhood. Caribbean Review of Gender Studies, 4 (http://www2.sta.uwi.edu/crgs/february2010/journals/PlummerGeofory.pdf).

Plummer D., McLean A., & Simpson J. (2008). Has learning become taboo and is risk-taking compulsory for Caribbean boys? Caribbean Review of Gender Studies, 2 (http://sta.uwi.edu/crgs/september2008/journals/DPlummerAMcleanJSimpson.pdf).

Ramirez, R. L. (1999). What it means to be a man: reflections on Puerto Rican masculinity. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Reddock, R. (Ed.). (2004). Interrogating Caribbean masculinities. Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press.

Rich, A. (1980). Compulsory heterosexuality and the lesbian existence. Signs, 5(4), 631–660.

Rubin, G. S. (2011). Deviations: a Gayle Rubin reader. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

UNAIDS. (2010). Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

UWI. (2010). Statistical Review: Academic Year 2009/2010. Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies. Retrieved from http://www.mona.uwi.edu/opair/statistics/

Van Gennep, A. (1960). The rites of passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. French original 1908.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Commonwealth, UNESCO, and the University of the West Indies for their support. He would also like to thank the participants and the individuals and organizations who assisted with recruitment and to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Joel Simpson, and of Ian McKnight and the late Robert Carr in the Jamaican arm of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Plummer, D.C. Masculinity and Risk: How Gender Constructs Drive Sexual Risks in the Caribbean. Sex Res Soc Policy 10, 165–174 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-013-0116-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-013-0116-7