ABSTRACT

In response to rising health care costs associated with obesity rates, some health care insurers are adopting incentivized technology-enhanced wellness programs. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the large-scale implementation of an incentivized Internet-mediated walking program for obese adults and to examine program acceptance, adherence, and impact. A mixed-methods evaluation was conducted to investigate program implementation, acceptance, and adherence rates, and physical activity rates among program participants. Program implementation was shaped by national and state policies, data security concerns, and challenges related to incentivizing participation. Among 15,397 eligible individuals, 6,548 (43 %) elected to participate in the walking program, achieving an average of 6,523 steps/day (SD 2,610 steps). Participants who uploaded step counts for 75 % of days for a full year (n = 2,885) achieved an average of 7,500 steps (SD 3,093). Acceptance and participation rates in this incentivized Internet-mediated walking program suggest that such interventions hold promise for engaging obese adults in physical activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The rapid rise in obesity in the USA has had profound implications for health care costs. Not only does obesity account directly for as much as 6 % of adult medical expenditures [1], it also increases the risk of costly chronic health conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and certain cancers [2–5]. The escalating health care costs associated with obesity have spurred policies and regulations that emphasize the importance of obesity and chronic disease prevention [6, 7]. Motivated by these policies, as well as potential cost savings, many employers and insurance companies now offer wellness programs that target obesity and promote healthy behaviors [8–10]. Early assessments of these programs suggest that they may improve health outcomes while simultaneously reducing health care costs [11], with one meta-analysis demonstrating savings of $3.27 in medical costs and $2.73 in absenteeism costs for every dollar spent on a workplace wellness program [8].

While traditional wellness programs include features such as health risk screenings, on-site gym facilities, disease self-management classes, and personal coaching [8], Internet-mediated behavior change interventions are becoming increasingly common [9]. These interventions have evolved from simple static displays of health promotion and disease prevention messages to complex, personally tailored and interactive interventions that significantly improve health behaviors [12, 13]. Some worksite wellness programs have incorporated monitoring tools such as pedometers that transmit detailed step-count data over the Internet and produce automated, personally tailored feedback. One benefit of these Internet-mediated interventions is their potential for population-level implementation at low cost. While initial intervention development may be expensive, the return on investment is attractive to payers because of their scalability and low marginal cost per participant compared with more traditional in-person interventions.

Internet-mediated health behavior change interventions that incorporate objective physical activity monitoring and automated, individually tailored feedback have been shown to increase physical activity in randomized controlled trials [14–16]. It is not yet clear, however, how such programs perform when deployed at a population level, where regulations, policies, and marketing challenges constrain intervention design and implementation. Furthermore, in these population-level programs, individuals may be less motivated to participate and less tolerant of an intervention’s complexity than those who choose to enroll in a clinical trial. In order to increase wellness program participation and adherence, many employers and insurance companies have begun to offer financial incentives [17], but the effectiveness of these incentives outside of clinical studies is not well established.

In 2010, a large US insurance company located in the Midwest launched an incentivized Internet-mediated wellness program for its obese enrollees. We conducted a mixed-methods study in order to: (1) understand organization level, policy, and marketing forces that affected program design and implementation and (2) determine whether it is possible to achieve broad acceptance, adherence, and impact with a population-wide incentivized technology-enhanced wellness program.

METHODS

Description of incentivized Internet-mediated walking program

In 2010, Blue Care Network (BCN) of Michigan launched an innovative wellness program (Healthy Blue Living (HBL)) in which BCN enrollees who commit to healthy lifestyles are eligible for enhanced benefits (reduced deductibles and copayments). Healthy Blue Living participants must either meet established targets for specific measures (i.e., body mass index (BMI) of <30 kg/m2, blood pressure < 140/90, and no tobacco use) or enroll in BCN-sponsored programs that focus on improving those specific health measures. Members with BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 have the option of joining an Internet-mediated walking program delivered by Walkingspree (San Antonio, TX), or participating in other employer-sponsored weight management programs such as Weight Watchers.

BCN’s walking program is a multi-component automated Web-based lifestyle change intervention. The central component is the Walkingspree program, which provides users with an uploading pedometer, guided step-count goal setting and Web-based feedback. Additional components include an online community, motivational and informational messaging, and a diet logging component (Fig. 1). Participants have access to customer feedback for trouble shooting. The standard Walkingspree program also includes a challenge program with competitions and prizes but this component was not implemented for the Healthy Blue Living program.

Individuals who enroll in BCN’s walking program receive a free pedometer (Omron HJ-720 ITC) that uploads detailed step-count data to the Internet and stores up to 42 days of data. The pedometer has been validated when worn in a number of different locations on the body, including in a pocket or on a waist belt, and participants are given instructions about how to wear the pedometer to obtain accurate step count readings. The program requires that they upload their pedometer readings at least once every 30 days and walk an average of 5,000 daily steps in each three-month period (or a minimum of 450,000 steps each quarter) in order to maintain eligibility for enhanced benefits. Those benefits amount to an estimated 20 % savings in out-of-pocket expenses (translating to savings of $2,000 for some families, so the incentives for participating and meeting step-count goals can be substantial).

Evaluation of factors influencing implementation of the incentivized walking program

In order to evaluate the forces that shaped BCN’s implementation of the Internet-mediated walking program, we conducted a qualitative study using principles from implementation research [18]. The goal of implementation research is to promote systematic use of evidence-based practices in activities of national, regional, and individual healthcare organizations [19]. Formative evaluations of implementation processes and related decisions enable researchers to collect credible information about the effectiveness and transferability of implementation strategies [20], leading to knowledge about what works where and why [21].

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) incorporates constructs from existing implementation theories into a single comprehensive framework that can help guide systematic formative evaluations of implementations [22]. The CFIR comprises five interacting domains of constructs that have been found to influence implementation effectiveness across a wide range of scientific disciplines. These domains include characteristics of the intervention (e.g., adaptability and complexity), the implementation process (e.g., the quality and nature of the process itself), the individuals implementing the intervention (e.g., beliefs and attitudes toward a new program or intervention), and the outer (e.g., policies) and inner settings (e.g., leadership engagement) in which the intervention is being implemented.

We used a snowball sampling technique to identify BCN employees who led the implementation of the Internet-mediated walking program. We first spoke with BCN’s Chief Medical Officer, then five individuals whom he recommended, followed by one more individual who was recommended by the others. In total, we identified seven individuals (from the divisions of medical affairs, information technology, actuarial services, finance, and program development), all of whom agreed to participate. Interviews, which were conducted by a member of the research team, ranged from 25 to 70 min and were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participation was voluntary, and there were no associated direct benefits to individuals.

A semi-structured interview guide was developed based on relevant CFIR constructs. For example, in exploring the influence of outer setting constructs, interviewees were asked about the local, state, or national policies, regulations, or guidelines that influenced decisions regarding how to implement the incentivized Internet-mediated walking program. In addition, they were asked how member needs factored into the decision to implement the program, and whether BCN was influenced by competitors implementing similar programs. Interviewees were also asked about key factors that facilitated or impeded the implementation process. After each question, the interviewer probed to delve more deeply into interviewees’ responses. We also obtained copies of BCN internal documents, including marketing materials and communications with Walkingspree, which provided detailed descriptions of the plans and requirements for the program.

Established qualitative content analysis procedures were utilized during coding and analysis of interview transcripts [23, 24]. A codebook was developed based on CFIR constructs and definitions and applied deductively to the qualitative data, and then refined and expanded based on themes that arose inductively from the data [23]. All interviews were coded by at least two study team members and then four study team members used a consensus approach to generate themes regarding how CFIR constructs influenced implementation of the program [23, 25].

Evaluation of program acceptance, adherence, and impact

Acceptance

To assess program acceptance, we analyzed three sources of de-identified data obtained from BCN and Walkingspree. First, we calculated the percentage of eligible members who enrolled in the walking program. Second, satisfaction results were obtained from an online participant program satisfaction survey, conducted from 11–25 August 2011. 780 respondents completed the survey; 12 % of those then-enrolled in the BCN Walkingspree program. Respondents were asked, "To receive higher benefits, your insurance coverage required you to sign up with … Walkingspree (or another employer-sponsored program). Do you feel this requirement was worthwhile to lower your health expenses and increase your overall health?" Respondents could answer, "Yes," "No," or "When I first signed up, I was not happy but now I value the opportunity." Participants could also enter open-ended comments. Third, Walkingspree provided online forums where participants could interact with each other. Some of the forum discussions focused on dissatisfaction with the program. Open-ended comments from the survey and from the forums were qualitatively coded by one researcher to identify themes and to extract representative quotes.

Adherence

We assessed adherence using time-stamped step-count data that participants uploaded to the Walkingspree website. We examined the percentage of enrolled days for which participants uploaded pedometer data, and the average daily step counts for all participants who uploaded data. We also determined the number of participants who completed quarterly check-ins and the percentage who met step-count goals and maintained eligibility for reduced copays and deductibles. For all adherence analyses, day of uploaded step-count data was considered valid if the total steps recorded on that day were between 99 and 25,001 steps, and if the recording was not from a participant's very first upload day, which likely represented only a partial day of data.

The number of days of enrollment was calculated as the number of days between a participant’s enrollment date and 29 July 2011. Step-count data for enrollees was available through 8 August 2012. Because there were days during which participants did not wear their pedometers and because some participants dropped out of the program and stopped uploading, step-count data were not available for every day for every participant. To address this problem of missing data, average daily step-counts were calculated using two methods. A low or conservative estimate was calculated by assuming that on those days that the pedometer was not worn, the participant took 0 steps. This method is particularly relevant to this program because it is the method that was used by BCN to determine if a participant had met the 5,000 step/day average in order to continue to be eligible for the HBL program. This method underestimates the true step-count averages. A second method consisted of dropping days with missing step-count data by not including them in either the numerator or the denominator for the average. This method is likely to overestimate the true step-count average because participants tend to be more sedentary on days that they fail to wear their pedometer.

Impact

We assessed the program’s impact on physical activity by analyzing participants’ step counts. Because there was no way to assess step counts before the participants started wearing pedometers, initial step counts may not represent baseline activity levels. Nevertheless, we examined changes in step counts to evaluate whether participation was associated with increased physical activity patterns over time in a subgroup of participants who were adherent to the program. Individuals were included in the adherent subsample if they (1) enrolled in the program between 1 October 2010 and 29 July 2011, and (2) uploaded valid step-count data for a minimum of 75 % (274/365) days between enrollment and one full year of program participation. This subgroup was used to examine trends in step-count changes over 1 year among participants engaged in the program. Analyses were adjusted for seasonal variation to account for an observed seasonal effect on step counts, with the lowest average steps in January and the highest in July. To estimate change in average step count by week in program, we fitted a linear regression with average daily step count per participant each week as the dependent variable. Independent variables included: (1) week of program, (2) average step count during the first week, (3) a single dichotomous variable to allow modeling of the change in slope during the first 4 weeks of the program as compared with the remaining program weeks, and (4) a sinusoidal variable for seasonal adjustment. All analyses accounted for clustering by individual participant.

The study was approved by the BCN Research Review Committee but data collection, analyses, and manuscript preparation were conducted independently without influence from this committee. Given the study’s focus on organizational processes, and its use of de-identified data about individual participants, it was considered exempt from regulation by the University of Michigan institutional review board.

RESULTS

Factors that influenced implementation of the incentivized walking program

Interviews with BCN leadership revealed that implementation of the walking program was influenced by a number of forces in the outer setting (e.g., federal policies and rising costs associated with obesity) and inner setting (e.g., organizational culture and support from leadership), as well as factors associated with the intervention (e.g., program design and flexibility of vendor) and the implementation process (e.g., short time frame). Examples of interviewees’ comments describing these and other influences defined by the CFIR framework are provided in the Appendix. In addition, there were three cross-cutting themes that highlight some challenges that are specific to the implementation of an incentivized wellness program. These are described below, highlighted by interviewees’ comments in quotes.

-

1.

State and federal policies affecting program structure

BCN leaders noted that great efforts were made to ensure that the new program met legislated requirements: “We wanted to make sure … that we were interpreting wellness incentives appropriately and as the legislation dictates.” For example, the state of Michigan permits insurers and HMOs to offer incentivized wellness programs as long as employers provide evidence of “improvement in the members’ health behaviors [26].” To meet these requirements, BCN structured incentives so that enrolled participants qualified for discounts based on their physical activity level rather than absolute or change in BMI: “There are some state rules around participation programs … So we could not say you have to lose 10 pounds to stay in this level of benefit; that would have been an outcome. So it’s really participation … [that] we needed to focus on.”

In addition, several federal policies constrained the nature and size of incentives that could be offered: “We always are very mindful of Department of Labor Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines as they are associated with wellness incentive plans,” said one interviewee. HIPAA’s nondiscrimination provisions generally bar employers that offer insurance to employees from discriminating on the basis of a health factor [27, 28]. However, an insurer may offer an incentivized wellness program that targets individuals with a specific health condition as long as the financial reward does not exceed 20 % of the cost of employee-only coverage under the plan: “The federal law is very clear: there can be a 20 % spread of the total healthcare cost.”

Similarly, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination against persons with a disability in privileges of employment, including health insurance benefits [29]. However, health insurers may alter coverage rates if there are “actuarial considerations that justify differential treatment of individuals with disabilities” [28, 30]. While being overweight is not generally considered an impairment, severe obesity, especially if it is the result of a physiological disorder, often qualifies as a disability under the ADA [31]. Thus, as described by one interviewee, “A physician can give a (reason why a patient) can’t reach a BMI of 30 and the health insurance, under the Americans with Disabilities Act … has to accept it.” As a result, BCN allowed members to get a signed waiver from a physician if they had a medical condition that precluded them from being able to achieve a BMI of <30 kg/m2. Waivers allowed members to qualify for the enhanced benefits without participating in either the walking program or the alternative weight loss program.

-

2.

Privacy and data security requirements for incentive eligibility

Financial incentives for program participation necessitated information sharing between BCN and Walkingspree. HIPAA’s “minimum necessary standard” limits disclosure of protected health information to that which is reasonably necessary to accomplish a given purpose [32]. One interviewee reported, “The biggest complication that we ran into was how do we, in support of HIPAA privacy minimum necessary rules… confirm [member] eligibility verification.” BCN leaders, in complying with this regulation, felt that they could not provide Walkingspree with any personal health information about BCN members, including their BCN member number or their name and address. This posed a challenge because they wanted to ensure that “only people who were eligible to sign up for the pedometer… could actually sign up.” BCN also needed to be able to link the step-count data tracked by Walkingspree with the BCN member identification number, in order to determine qualification for financial incentives: “It was difficult because we needed to determine how to make sure that all of our software and hardware was communicating the way that it should be and that those systems were then communicating with [the vendor] and vice versa.” Ultimately BCN assigned each member a unique code to use during the registration process, and then linked this code to the person’s BCN identification number to monitor their progress in the program.

-

3.

Tension between personalized goals and simplicity of incentive structure

One issue that arose in marketing the program was a need to unambiguously communicate the requirements for maintaining eligibility for financial discounts. Although the Walkingspree program had the capability to increase step-count goals over time, or allow participants to set personal targets, the BCN communication specialists did not want the program to include any fluctuating goals that might be a source of confusion about what step-count target was required for maintaining eligibility for discounted copays and deductibles. As described by one leader, “Customer Service says, ‘Averages are complicated; no one will ever be able to understand… We need to pick a number and go with a number.’” Another said, “We kept getting feedback that we can’t confuse our members. It has to be simple… You know, health insurance is confusing enough and then you complicate it with, well, you’ve got to do this, this, and this for that next month…” As a result, BCN decided to forego a personalized program (i.e., a program with individual, adjustable goal-setting capabilities) in favor of a single step-count requirement (5,000 steps/day) for all participants for the duration of the program.

Program acceptance, adherence, and impact

As of 29 July 2011, 79 % of the 57,212 members eligible for the Healthy Blue Living program completed the enrollment process, 15,397 (27 %) of whom had a BMI ≥ 30 (Fig. 2). About 17 % (n = 2,590) of the obese members opted not to participate in a program and another 5 % (n = 705) obtained a waiver from their physician on account of a medical condition. Among the remaining 12,102 eligible members, 54 % elected to participate in the Internet-mediated walking program and the remaining 46 % elected other weight management programs. The average BMI for those who chose Walkingspree was 35.2 kg/m2, and this was approximately 1.5 BMI points less than the BMI of the obese HBL participants who did not choose Walkingspree (p < 0.0001).

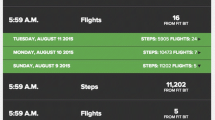

From 12 October 2010 to 29 July 2011, 6,519 (98 %) program participants uploaded step-count data to the website at least once, and cumulatively these participants uploaded valid step-count data for 85 % (620,995 of 729,908) of days during which they were enrolled in the program. Average daily step counts among all participants, counting 0 for days where the pedometer was not worn or data was not uploaded, was 6,523 steps/day (SD 2,610 steps). When days for which there was no valid pedometer data were excluded from analyses, the average daily step count was 7,610 (SD 2,490) steps/day.

Among participants who completed at least one quarterly check-in during the first 10 months of the program, only 3.3 % (146 of 4,430) failed to maintain eligibility for the reduced copays and deductibles because they did not meet the required step-count goal. Among the participants who uploaded step counts for an entire year following enrollment (n = 2,885), average step counts remained fairly stable after the first few weeks, with a modeled mean of approximately 7,500 steps (SD 3,093)/day after adjusting for seasonal variation (Fig. 3).

Mean and median steps per day among participants enrolled in incentivized, Internet-mediated walking program, adjusted for seasonal variation. The figure illustrates median steps per day, adjusted for seasonal variation (bottom) and modeled mean steps per day, adjusted for seasonal variation (top) for the subset of participants who were enrolled in the program, and uploaded their pedometer data, for an entire year (n = 2,885)

The incentivized Internet-based walking program was well-received by a majority of participants, although some perceived the financial incentives as coercive. In an optional Web-based survey (response rate 12 %), over half of the respondents (51 %) stated that they appreciated the value of the program for decreasing their health care costs and improving their health outcomes: “This is really my first month here, and already I have seen some weight loss. This program has inspired me to actually do something about losing weight, instead of just thinking about it. I now look forward to cutting the grass just for the steps.” An additional 17 % were initially unhappy with the program and joined because of the financial incentive but after being in the program they converted to appreciating the program benefits: “When I first started this I wasn't sure, and kind of thought it would be annoying especially since I was being forced to do it. But after a while I find myself trying to beat my other days’ worth of numbers. It's kind of fun.” The remaining 31 % did not like the program and many of these noted in free text responses that they felt forced to participate on account of the financial incentives: “I don't enjoy being forced to sign up for something just because I don't fit into outdated guidelines for healthiness. Could I afford to lose some weight? Yes. But I'd prefer to do something about it because I wanted to, not because it was required.”

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the large-scale implementation of an insurance-incentivized, Internet-mediated walking program; an innovative intervention addressing the costly challenges posed by obesity and sedentary behavior. Program acceptance, as determined by enrollment levels, was extremely high, although close to one third of participants reported they did not like the program and some described the financial incentives as coercive. Approximately two thirds of survey respondents stated that they appreciated the health benefits of the program, and preliminary data suggest that individuals who participated for a full year maintained daily step counts well above the established goal.

Our interviews with BCN leadership revealed several forces in the political and social environment that influenced implementation of the incentivized walking program, including compromises from what prior research suggests would have been most effective. First, a number of policies, most notably HIPAA and the ADA, shaped the nature and size of incentives that were offered for participation. Second, considerations about privacy and data security drove BCN decisions about how to monitor participation to track eligibility for incentives. Finally, concerns about numeracy of members led to decisions by leadership to forego a more individualized program. These influences confirm the importance of considering the Outer Setting domain, as described by the CFIR, in our evaluation framework [22]. Specifically, these influences align with the “External Policy and Incentives” construct which includes external mandates (e.g., HIPAA and ADA) and with the “Patient Needs and Resources” construct in terms of the attention given to protecting patient privacy (Appendix).

Once implemented, the program achieved high levels of acceptance and adherence by members. These rates are noteworthy because they dwarf participation and adherence rates in randomized controlled trials of similar programs without financial incentives. For example, in contrast to the 79 % enrollment rate (the proportion of eligible individuals who enrolled in one of BCN’s incentivized wellness programs) observed in this population-wide intervention, a previous randomized controlled trial with a comparable population had an enrollment rate of 5 % [14]. Of note, some of the participants’ reactions to the program indicate that the program’s effect came at a cost of ill-will from some individuals who felt coerced to participate. While most of these members later appreciated the benefits of the program, nearly a third of them did not like the program, even in retrospect. Nevertheless, given the mounting costs associated with sedentary behavior, approaches to financially incentivize healthy behaviors are likely to expand and gain political support, as has occurred with cigarette taxes and more recently with discussions about taxes on high-sugar beverages [33].

Our step-count analyses suggest that the majority of participants were able to maintain step counts above the established goal. Furthermore, although response rates to the survey were low, the findings suggest that some program participants experienced health benefits such as weight loss. While 5,000 steps/day is a fairly modest goal at first glance [34], randomized controlled trials of individuals who are overweight or obese have revealed average baseline step counts of only 4,441/day in comparable populations [14] (a figure that may be an overestimate of the true population average because individuals who are sedentary are probably less likely to voluntarily enroll in a walking program, and the act of enrolling in a study and wearing a pedometer is likely to induce walking). Additional evaluations will be necessary to determine whether the activity levels observed in this study translate to improved clinical outcomes and changes in health care utilization and costs.

While we are unable to determine how much the financial incentives contributed to participation and adherence rates, nearly half of the respondents to the Web-based survey indicated that they joined the program at least in part for financial reasons. Others who reported that they appreciated the value of the program might not have joined without the substantial financial incentive. These findings are consistent with results from previous studies examining the impact of incentives in health behavior change programs [35–38], which affirm that financial incentives for participation and adherence, when sufficiently large, can motivate activity. It is not clear, however, exactly how large the incentives have to be in order to achieve this level of participation and program adherence.

The incentivized component of this program raises a number of ethical considerations that warrant discussion. The incentive associated with this program (estimated savings that can approximate close to $2,000/year for some families) was much larger than any financial benefit that would be authorized in a clinical trial. As such, this type of program would likely not receive approval from an institutional review board for evaluation in a clinical trial. Other ethical issues emerge when implementing an incentivized wellness program on a population level [28, 39, 40]. For example, incentivized programs can result in a “social gradient” where individuals with fewer resources, including less time and less access to healthy activities, may not be able to meet the requirements that are necessary to receive financial benefits [41, 42]. While some protections related to discrimination, for example against individuals with disabilities, are already in place in existing legislation, more protections may be needed to prevent unintended and socially regressive impacts as these programs proliferate.

Several limitations to this study warrant discussion. First, we chose to conduct an in-depth evaluation of a single component of one insurance company’s wellness program. Thus, generalizability is a concern. However, given the size and scope of BCN’s Healthy Blue Living service coverage, the forces shaping this particular company’s implementation decisions are likely to resonate widely with others. In addition, our assessment of forces influencing implementation was based on interviews with only seven individuals, although we used a snowball technique in order to identify as many individuals as possible who had an instrumental role in the implementation process, and all individuals invited to participate did so. Finally, as with all natural experiments, our analyses were limited to available data. For example, we were unable to assess whether physical activity changed significantly in response to the intervention because we did not have access to participants’ baseline step counts prior to the program’s start. We also did not have information about individuals who chose not to participate in the program, thereby limiting our understanding of the program’s reach. Nevertheless, the step counts observed among participants were substantially greater than those seen at baseline among comparable individuals in clinical trials [14].

This study contributes to our understanding of the potential value of a large-scale, incentivized, Internet-mediated wellness program. A number of policies associated with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) are likely to intensify current efforts by employers and insurance companies to develop these types of wellness programs. For example, the PPACA requires that all individual, group, and health insurance exchange health plans cover “Preventive and Wellness Services and Chronic Disease Management” (PPACA, Sec. 1302) [43]. In addition, PPACA will expand on HIPAA’s Healthy Lifestyle Discounts by allowing employers to offer a premium discount of up to 30 % (instead of 20 %) for participating in wellness programs (PPACA, Sec. 2705) [43]. Such policies are likely to stimulate increased adoption and incentivization of wellness programs by insurers and employers.

In summary, our evaluation of this program’s implementation, acceptance, adherence, and impact suggests that insurance-incentivized, Internet-mediated wellness programs hold promise for encouraging physical activity in obese adults. The impressive rates of program enrollment and adherence, and the sustained activity levels that we observed among engaged participants, warrant a longer-term and more comprehensive evaluation to fully understand the program’s impact on clinical outcomes and health care utilization and costs.

REFERENCES

Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G. State-level estimates of annual medical expenditures attributable to obesity. Obes Res. 2004;12:18-24.

Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Ben-Joseph RH. The effect of obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors on expenditures and productivity in the United States. Obesity. 2008;16:2155-2162.

Wolf AM, Finer N, Allshouse AA, et al. PROCEED: prospective obesity cohort of economic evaluation and determinants: baseline health and healthcare utilization of the U.S. sample. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:1248-1260.

Field AE, Coakley EH, Spadano JL, et al. Impact of overweight on the risk of developing common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1581-1586.

Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:579-591.

New York Times. Obama's health reform speech. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/15/health/policy/15obama.text.html. Accessed 8 December 2010.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Comprehensive Workplace Health Programs to Address Physical Activity, Nutrition, and Tobacco Use in the Workplace. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/nhwp/index.html. Accessed 6 November 2012.

Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:304-311.

Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust. Employer Health Benefits 2010 Annual Survey: Wellness Programs, Health Risk Assessments, and Disease Management Programs. Available at http://ehbs.kff.org/2010.html. Accessed 7 November 2012.

Okie S. The employer as health coach. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1465-1469.

Pelletier KR. A review and analysis of the clinical and cost-effectiveness studies of comprehensive health promotion and disease management programs at the worksite: update VII 2004–2008. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:822-837.

Kroeze W, Werkman A, Brug J. A systematic review of randomized trials on the effectiveness of computer-tailored education on physical activity and dietary behaviors. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:205-223.

Strecher V. Internet methods for delivering behavioral and health-related interventions (eHealth). Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:53-76.

Richardson CR, Buis LR, Janney AW, et al. An online community improves adherence in an Internet-mediated walking program. Part 1: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e71.

Slootmaker SM, Chinapaw MJ, Schuit AJ, Seidell JC, Van Mechelen W. Feasibility and effectiveness of online physical activity advice based on a personal activity monitor: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e27.

Ware LJ, Hurling R, Bataveljic O, et al. Rates and determinants of uptake and use of an Internet physical activity and weight management program in office and manufacturing work sites in England: cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e56.

Capps K, Harkey JB. Employee health and productivity management programs: The use of incentives, a survey of major U.S. employers. Available at http://www.healthcarevisions.net/f/2008_Use_of_Incentives_Survey-Results-2008.pdf. Accessed 10 August 2012.

Alegria M. AcademyHealth 25th Annual Research Meeting chair address: from a science of recommendation to a science of implementation. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:5-14.

Rubenstein LV, Pugh J. Strategies for promoting organizational and practice change by advancing implementation research. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S58-S64.

Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S1-S8.

Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ. A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:194-205.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Forman J, Damschroder LJ. Qualitative content analysis. In: Jacoby L, Siminoff L, eds. Empirical research for bioethics: a primer. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2008.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: a sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:781-820.

Michigan Senate Bill. No 849, Sec 414b (2006).

U.S. Department of Labor. FAQs about the HIPAA nondiscrimination requirements. Available at http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/faqs/faq_hipaa_ND.html. Accessed 10 December 2010.

Mello MM, Rosenthal MB. Wellness programs and lifestyle discrimination—the legal limits. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:192-199.

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, as Amended. Available at http://www.ada.gov/pubs/adastatute08.htm. Accessed 6 November 2012.

Department of Justice. Americans with Disabilities Act: Title III technical assistance manual covering public accommodations and commercial facilities. Available at http://www.ada.gov/taman3.html. Accessed 14 December 2010.

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Section 902 Definition of the Term Disability: Notice concerning The Americans With Disabilities Act Amendments Act Of 2008. Available at http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/902cm.html. Accessed 10 December 2010.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Minimum necessary requirement. Available at http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/coveredentities/minimumnecessary.html. Accessed 10 December 2010.

Wang YC, Coxson P, Shen YM, Goldman L, Bibbins-Domingo K. A penny-per-ounce tax on sugar-sweetened beverages would cut health and cost burdens of diabetes. Heal Aff. 2012;31:199-207.

Tudor-Locke C, Hatano Y, Pangrazi RP, Kang M. Revisiting "how many steps are enough?". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:S537-S543.

Charness G, Gneezy U. Incentives to exercise. Econometrica. 2009;77:909-931.

Volpp KG, Gurmankin Levy A, Asch DA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:12-18.

Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:699-709.

Gneezy U, Rustichini A. Pay enough or don't pay at all. Q J Econ. 2000;115:791-810.

Redmond P, Solomon J, Lin M. Can incentives for healthy behavior improve health and hold down Medicaid costs? Available at http://www.cbpp.org/6-1-07health.pdf. Accessed 14 December 2010.

Steinbrook R. Imposing personal responsibility for health. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:753-756.

Schmidt H, Gerber A, Stock S. What can we learn from German health incentive schemes? BMJ. 2009;339:b3504.

Schmidt H, Voigt K, Wikler D. Carrots, sticks, and health care reform–problems with wellness incentives. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:e3.

Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act. P.L. 111–148. Available at http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=111_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ148.111.pdf. Accessed 14 December 2010.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank BCN leadership and employees for participating in interviews and Emily Jenchura, Danielle Cohen, and Jill Bowdler for their assistance with manuscript preparation.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Zulman’s contribution to this study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program and an associated Advanced Fellowship through Veterans Affairs. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

Dr. Richardson is a scientific advisor to Walkingspree and an unpaid consultant to BCN. She does not receive compensation in these roles and does not have a financial interest in either company. The authors report no other competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Implications

Practice: Insurance-incentivized Internet-mediated walking programs are acceptable to many obese adults and enable them to meet modest physical activity goals; however, some may perceive the financial incentives as coercive.

Policy: The Affordable Care Act’s incentivized wellness program policies should be evaluated to determine how such policies affect program adoption and implementation, and whether the policies successfully lead to improved health behaviors at a population level.

Research: Future research is needed to determine the impact of incentivized Internet-mediated walking programs on health outcomes and medical care costs.

Appendix

Appendix

Factors influencing implementation of an incentivized Internet-mediated walking program (examples of interviewees’ comments mapping to CFIR constructs)

CFIR constructs | Examples |

Outer setting | |

External polices and incentives | “We always are very mindful of Department of Labor HIPAA guidelines as they are associated with wellness incentive plans” |

“And we know there has been a lot of discussion nationally and here at Blue Care Network as a health insurance carrier, about the alarming obesity trends that are going on out there” | |

“There are some state rules around participation programs … So we couldn’t say you have to lose 10 pounds to stay in this level of benefit; that would have been an outcome. So it’s really participation … (that) we needed to focus on” | |

Patient needs and resources | “You know, there were individuals who were like, oh boy, some members aren’t going to like that. And they’re right. And we need to be prepared to assist those members in understanding why we’re doing what we’re doing and how it’s going to benefit them” |

“We’re doing the right thing for membership … Helping promote more activity, more wellness, and that, in turn, drives healthcare premiums down, which everyone is after” | |

“The need of the enrollee is to maintain a healthy lifestyle, and that is definitely consistent with our goal. Now, it may not be a cognitive—it may not actually realize that’s one of their goals, but all of us want to be healthy. And I think that recognizing that in a sort of generic global way, that all of us want to be healthy, we did recognize and identify directly with the member. The second piece, which everybody recognizes, especially in a dull economy, is the need to reduce healthcare costs. And I think cost of healthcare generally is identified by the member in terms of the cost of insurance. And so, with this program … there is the possibility with the enhanced program with lowering your premium. So I think that the member was absolutely central to the decision” | |

“I think probably the biggest thing was what would be the impact on a daily basis to the member; how inconvenient would it be; how intrusive would it be; how would the information be kept confidential so that they weren’t worried that someone was going to have view of what they’re doing … It’s internet based so you have to have internet access and the personal email” | |

Peer pressure | “We did do some external benchmarking. We’re kind of in the forefront of the healthy products suites … we were the first in the market with the Healthy Blue Living product in the country and so we try to continue to work in cutting edge, but we did do some external benchmarking … We didn’t find any health plans that offered (a program like this) as a specific option or requirement” |

Inner setting | |

Organizational goals | “We really want to improve the overall health status of our members. If we are able to accomplish that, then the reality is in the long term, healthcare costs will either stabilize or be less … Particularly dealing with obesity, if you can change the patient’s behavior as it reflects to obesity or lack of exercise, you can actually preclude certain conditions from arising and, therefore, increase health status and lower the overall cost of healthcare. So I think the first thing was health status; the second thing is lowering overall cost of healthcare; the third thing was member retention in our program. And member retention is important because of the cost of marketing for new membership. And the reason that this was a good member retention program (is because of reduced fees if you meet goals)” |

Structural characteristics | “I think the fact that the relationship between IT and the business is one of collaboration and partnership … made this go much faster and much better than it might in other organizations” |

Culture | “We’re constantly strategizing how we can improve the product, how we can make it more meaningful to the community, and what we can do overall to make it a better product” |

“We’re innovators!” | |

“Spirit of cooperation among all of the operational areas that are impacted” | |

“You know, it’s one thing to say, okay, we’re going to move forward with this; it’s another thing to do so in eight months, and have faith that your culture is going to support a successful launch or implementation and launch. And I think that our culture did support that belief and did support that faith and we were able to move forward” | |

“I think it helps (to) have a kind of culture of wellness in your company. Because we have people already that are into walking and we encourage walking and we promote walking for our employees, so I think that helps” | |

“We’re considered the product incubator, innovator in the enterprise, and I think we have a very ‘can do’ nimble approach that makes us not flinch when we get an assignment to build a product” | |

Implementation climate | “We really didn’t think we were moving BMIs in the right direction, having physicians be responsible for watching that kind of thing and working with their patients to improve their BMI … BMIs (were not) getting that much better … and the weight wasn’t coming down” |

“The economics of Michigan have been so severe and the changes in the delivery of healthcare are changing at a more rapid pace, and the cost is sky rocketing. And I think that we have just tried to be much more adaptive and inventive and imaginative in terms of how we can serve the Michigan population. So I’d say all those things certainly affected the decision making and the process and, again, are very consistent with our culture and our goals and objectives” | |

Intervention characteristics | |

Evidence strength/quality | “(We) worked with a leading expert on exploring what would be appropriate options” |

Relative advantage | “We looked at … what’s happening today in the physician office and we weren’t all that impressed that it was really happening” |

Design quality/Packaging | “We liked that (the vendor was) willing to offer us suggestions as to how to create a plan that our members would be able to comply with and actually be successful at” |

“We need(ed) a program that members could easily read and understand. We needed a customer service component that if members ran into trouble there was somebody there to either email or telephone to answer questions … So we needed a customer service component” | |

Trialability | “(The vendor) actually provided us with a select number of pedometers to use so that we could sort of be a pilot group … and we liked the results that we got” |

Intervention complexity | “It was difficult because we need to determine how to make sure that all of our software and hardware was communicating the way that it should be and that those systems were then communicating with (the vendor) and vice versa …” |

“I think a piece we struggled with was how many steps to make people walk. What’s the right number and how do you balance that with how many steps is the right number of steps and how can we efficiently monitor that, because you could make it very complicated. And that’s kind of the path we were going down originally and, oh, my gosh, that’s going to be really way too complicated. We were going to try to customize it, too. If you have a BMI of this, you need to walk this many steps; if your BMI is this, you need to walk this many. But that would have been an administrative nightmare. We got off of that right away” | |

Cost | “What we did was look at the cost associated with a member who has a BMI of 30 or above … what types of co-morbid conditions are we seeing these members develop? What amount of money are we paying out in claims for these members? … if we can work with these members and get them to achieve- and not even a huge weight loss but just a little bit of a weight loss and we can couple that with an improvement in respiratory health and an improvement in fitness level. All of those things are going to end up having a much higher pay off as far as decreased claims risk in the future” |

“It had to fit with the actuarial models in keeping the pricing so that it achieved the goals and improved the health … The expectation is improving the members’ health … in the long term of course … lowers healthcare costs. But the formulas don’t show a direct cost benefit as such” | |

Individual characteristics | |

Knowledge/beliefs about intervention | “Every department … had training … and each department had their own trainer … We’ve done a lot, a lot of employee communication to help people understand” |

“Certainly for our customer service representatives and our clinical health coaches, we had extensive training; we developed policies and procedures; rolled out communication; published articles internally promoting … the new changes to our product” | |

Self-efficacy | “Overall, I was quite confident. I worked with these people a few years and I know their level of commitment and their passion associated with this particular product, and I know that none of us wanted to not meet the goal. So I was confident that if there was a will, there was a way and that we would find it, and we did. But there were some days where, you know, we were a little challenged” |

“It was my job to do it; I was 100 % confident it was going to happen” | |

Identification with organization | “I think that it’s a wonderful thing that the corporation has put their money kind of where their mouth is …” |

“I’m very excited about this because this is what healthcare should be, you know, promoting health, trying to decrease health premiums to try to change health behaviors” | |

“I absolutely support the goals. I mean, what’s wrong with trying to make Michiganders happier? What’s wrong with lowering the overall cost of healthcare over a protracted period of time? What’s wrong with keeping your members because if you have to go out and market new members, you’re going to increase your costs … so any one of those are excellent goals” | |

Process of implementation | |

Key facilitators | “Overall the entire launch and implementation was very positive. I think that everybody involved was very proactive and very willing to do what needed to be done to make it happen. I think that our vendor was delighted to accommodate our every need and worked hard to do so, which is really very nice. They never lost sight of the fact that we were the customer, which is also very nice” |

“It was brought in from the top and the big belief that it was needed and nobody was against it” | |

Key barriers | “The only resource would have been to have more time. If we had more time, you know, but that just would have just made it more comfortable for everybody. We would have had an opportunity to maybe feel a bit reassured” |

“Operations is spread out over so many areas” | |

“I would say to you that the single most difficult problem with this project was being able to wrap our arms around and define explicitly what the product changes were going to look like, what were the decisions … associated with change, and how are we going to measure it and manage it. And I think it was very difficult because it was unchartered water … And there was some indecisiveness on the approach which probably elongated the project and it might have cost a little bit more because of that” | |

Planning, engaging, executing | “We have a very formal project implementation process. We use project management methodology. We have established work groups when we do an implementation … regular status reporting. So we adhere very strictly to (project management) methodology and that structure, and having … a dedicated project manager to sort of be the general contractor of the whole thing. I think it is key because (the others have day jobs). You need somebody who is kind of standing on the roof, having eyes and ears for all of it … (an) objective participant … (whose) stake is to collect the success of the initiative. Besides the hardcore methodology side, there’s the softer side of managing people, personalities, and it’s real helpful because there are some strong personalities in every group” |

Reflecting/evaluating | “So it’s going to be very interesting to see what happens and I think you've got some short term numbers but we've got to wait until we get the long term effect. Because changing healthcare behaviors is really not a short term issue; it’s a long term issue and it’s one that you have to have consistency and you have to have durability and what’s another word … extensibility over a protracted period of time. So, you know, let’s see in a year, let’s evaluate and look at what we’ve been able to accomplish and fine tune it and keep on going” |

Implementation complexity | “It was difficult because we need to determine how to make sure that all of our software and hardware was communicating the way that it should be and that those systems were then communicating with WS and vice versa …” |

“You know, to implement it as a product line, the biggest complication that we ran into was how do we, in support of HIPAA privacy minimum necessary rules, how do we confirm eligibility … and limit it” | |

About this article

Cite this article

Zulman, D.M., Damschroder, L.J., Smith, R.G. et al. Implementation and evaluation of an incentivized Internet-mediated walking program for obese adults. Behav. Med. Pract. Policy Res. 3, 357–369 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-013-0211-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-013-0211-6