Abstract

Objectives

There is an increasing recognition of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) as a promising way to reduce burnout. However, inconsistent results were found on the effect among college students. In addition, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The aims of this study were to explore the effect of a mindfulness-based training program on burnout in college student population and to examine if changes in mindfulness mediate the intervention effect.

Method

A total of 128 college students (M = 21.36 years, SD = 2.76 years) were randomized into an intervention group (n = 64) or a wait-list control group (n = 64). The intervention consisted of eight sections of mindfulness training courses. Measures on mindfulness and burnout were administered at the baseline, post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up.

Results

Compared to those in the control group, participants in the intervention group reported a significant increase in mindfulness and a decrease in burnout both at post-intervention (mindfulness: F = 22.41, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.15; burnout: F = 8.24, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.06) and 3-month follow-up (mindfulness: F = 16.29, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.12; burnout: F = 9.24, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.07). Mediation analyses demonstrated that the increase in mindfulness fully mediated the intervention effect on burnout.

Conclusions

Mindfulness-based training programs can effectively reduce burnout among college students, and the effect appears to be mediated by changes in mindfulness levels.

Preregistration

This study is not preregistered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Burnout is a psychosocial syndrome people increasingly experience in modern society (Koutsimani et al., 2019). When someone is in the state of burnout, it may refer to that he or she has been overextended and is depleted of energy and resources, tends to develop negative and detached attitudes towards excessive demands, and generates reduced feelings of competence and achievement at work (Bakker & de Vries, 2021). Burnout has been found to be associated with a series of negative consequences, such as lower level of work engagement (Hakanen et al., 2006) and job satisfaction (Appelbaum et al., 2019; Scanlan & Still, 2019), and higher level of turnover intention (Liu et al., 2018; Scanlan & Still, 2019; Van der Heijden et al., 2019). In addition to occupational influences, long exposure to chronic stress may put one’s health state at risk. Physical problems like heart diseases (Appels & Schouten, 1991; Toker et al., 2012), cardiovascular disorders (Toppinen-Tanner et al., 2009), musculoskeletal pain (Armon et al., 2010; Langballe et al., 2009; Melamed, 2009), and psychological influences including insomnia (Vela-Bueno et al., 2008), depression (Hakanen et al., 2008), and other psychological distress or mental disorders may all be the results of burnout.

The concept of burnout was initially restricted to human services domain as the universally used Maslach Burnout Inventory defined three dimensions all referring to the relationship between provider and recipient (Demerouti et al., 2001; Maslach et al., 2001). Currently, more attention has been paid to a broader range of groups. The exploration outside the traditional concept made it possible to investigate more types of professions (Schutte et al., 2000). Numerous studies have pointed out that burnout can be experienced by students as well (Ishak et al., 2013; Santen et al., 2010; Schaufeli et al., 2002). Students, especially college students, have to cope with challenging workload to make themselves experts in their professions, as well as go through demanding social pressures and complex interpersonal relationship, which may put them under the risk of burnout. For them, burnout is manifested as a feeling of exhaustion due to high demand of study, a distant attitude towards study, and an incompetent sense of achieving academic value (Hu & Schaufeli, 2009).

It is essential to address the problem of burnout among college students. Burnout is found prevalent among the population of college students, with the prevalence ranging from 7.00 to 71.00% (Al-Alawi et al., 2019; Almeida et al., 2016; Atalayin et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2012; Cook et al., 2014; dos Santos Boni et al., 2018; Fitzpatrick et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2020; Mafla et al., 2015; Mazurkiewicz et al., 2012; Santen et al., 2010; Vidhukumar & Hamza, 2020). It is also found to be associated with a wide range of negative outcomes, including decreased academic efficacy (Atalayin et al., 2015), low academic satisfaction (Atalayin et al., 2015), low academic achievement (Atalayin et al., 2015; Yang, 2004), low self-efficacy (Capri et al., 2012; Rahmati, 2014), low self-esteem (Dahlin et al., 2007), sleep disorder (Pagnin et al., 2014), and suicidal ideation (Dyrbye et al., 2008).

In view of the consequences, it is vital to identify and address protective factors of burnout. Recent studies indicate that mindfulness may serve as a personal trait that buffers against burnout (Harker et al., 2016; Kemper et al., 2019; Salvarani et al., 2019; Taylor & Millear, 2016; Vilardaga et al., 2011). The concept of mindfulness has its root in Buddhism (Brown & Ryan, 2003), and is most commonly defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn, 2003, p.145). It has been adopted as an approach to skillfully bringing attention to moment-to-moment experience (Bishop et al., 2004).

Recent research has demonstrated that the improvement of mindfulness through training facilitates various well-being outcomes, including burnout (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Luken & Sammons, 2016). Overall, studies have found that mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) can effectively reduce burnout among a wide range of occupations, including occupational therapy practitioners (Luken & Sammons, 2016), primary healthcare professionals (Salvado et al., 2021), physicians (Fendel et al., 2021), nurses (Green & Kinchen, 2021; Suleiman-Martos et al., 2020), teachers (Flook et al., 2013; Roeser et al., 2013), and athletes (Li et al., 2019). For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis including 17 articles of 632 nurses revealed that mindfulness training could effectively reduce the level of burnout, generating lower scores in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and higher scores in personal accomplishment (Suleiman-Martos et al., 2020). Studies conducted on teachers also showed that compared to those in the control condition, teachers in mindfulness training reported significantly less burnout at post-program and 3-month follow-up (Roeser et al., 2013). These results indicated that MBIs may be of benefit for various populations to cope with burnout problems (Baer, 2003; Kabat-Zinn, 2003).

Though numerous studies have verified the effect of MBIs on the alleviation of burnout, only few of them were conducted in college student population, with inconsistent findings being reported. Garneau et al. (2013) found that, after taking a 4-week mindfulness medical practice, 58 medical students had statistically significant improvement on burnout subscale of emotional exhaustion. However, Barbosa et al. (2013) examined the impact of an 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) training on burnout in 28 graduate healthcare students and found no significant differences at Weeks 8 and 11 between those in the intervention and control groups. Similarly, the effect of a 7-week MBSR program was test by de Vibe et al. (2013) in 288 medical and psychology students, and the results showed no statistical significant effect on burnout. Oro et al. (2021) also evaluated the effect of a 16-week mindfulness-based program in 143 medical students and found no positive results.

In addition, some researchers have questioned the underlying mechanisms of MBIs, that is, whether the interventions really take effect through heightening the level of mindfulness, rather than placebo effects. For example, Davies et al. (2021) found that a sham mindfulness intervention generated equivalent credibility ratings and expectations of improvement for pain as a mindfulness intervention. Another study (Noone & Hogan, 2018) investigated the effects of an online MBI and found significant increases in mindfulness dispositions and critical thinking scores in both the mindfulness meditation and sham meditation groups.

Thus, the aims of the present study were to test the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based training program on the alleviation of burnout among college students in China, and explore the potential mechanisms underlying the process. We hypothesized that the mindfulness training program could significantly reduce burnout in the studied sample, and changes in mindfulness level would statistically mediate the intervention effect on burnout.

Method

Participants

Participants were accessed and recruited in October 2021 via advertisements on the school website. The study was available to all full-time college students in Zhejiang University. Students interested in the study were then invited to join a WeChat group for further communication. Format of the program was explained and questions related to participation were answered. Inclusion criteria required participants to be full-time college students at Zhejiang University, while exclusion criteria included severe psychopathology and/or alcohol/drug abuse in the past 6 months. The exclusion criteria were set to exclude participants as high risk for ethical consideration, as well as avoid the potential impact of their medication use on the intervention effect.

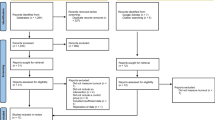

Of 152 accessed students, 24 withdrew due to schedule conflicts. Thus, a total of 128 participants were involved in the study. All participants were provided with the informed consent documents prior to participation. They were then randomly allocated to the intervention group (n = 64) or the wait-list control group (n = 64). After the allocation, the intervention group received an 8-week mindfulness-based training program in Winter 2021, while those in the control group took part in daily school activities as usual and were scheduled to participate in the same program after the formal study procedure ended. Measures were administered at baseline, post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up. Ten participants in the intervention group dropped out during the program due to schedule conflicts (n = 5) or other personal issues (n = 5). The average attendance for the 8-week program was 5.27 (SD = 2.47), with 36 (56.25%) participants attending 75% and more of the sessions. All participants including those dropped out completed the post-intervention questionnaire, while 4 participants in the intervention group and 7 in the control group failed to complete the 3-month follow-up survey (Fig. 1).

Sample size was determined based on power analyses performed using G*Power software version 3.1. An intervention effect with an effect size of 0.25 (Cohen’s d) was adopted based on a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of relevant research (Hathaisaard et al., 2022). With an alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, 86 participants were estimated to be included in the study. Considering an estimated withdraw rate of 25%, a minimum of 108 participants were required and the current sample size was satisfactory. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Zhejiang University.

Procedure

The training program delivered was completely aligned with the MSBR training courses developed by Kabat-Zinn (1982) and referred to a MBSR website (https://palousemindfulness.com). The only adaptation we made was to replace those materials in English, such as instructions and videos, with Chinese ones, which translations had been examined with acceptable validity in our previous research (Zhu et al., 2019).

It was a structured group program that focuses upon the progressive acquisition of mindfulness awareness. The program consisted of a 1.5-hr once-weekly small-group format for eight sessions in a quiet, spacious, comfortable activity room in on-campus student housing. The training program consisted of five primary components: (a) homework review; (b) theoretical teaching; (c) experiential practice; (d) group discussion; and (e) homework assignment. The framework of the program can be found in the supplementary material. Each session covers a particular topic with several mindfulness meditation skills being taught, such as body scan, sitting meditation, hatha yoga, and loving-kindness. Apart from the formal meditation practices, several informal practices were presented through the program, such as simple awareness, STOP, and turning toward. A booklet containing information pertinent was provided after each week’s instruction, as well as audiotapes of guided mindfulness exercises. Participants were required to practice mindfulness meditation outside the group meetings for 6 days per week with at least 30 min per day. In addition, participants were also encouraged to practice mindfulness in daily life, like eating, standing, and walking mindfulness.

The program was delivered by the first author, who has more than 2 years of personal practice and training delivery experiences of mindfulness in college students and hospital nurses, with the supervision of the third author, who has received mindfulness training from the Harvard Medical School and has more than 10 years of personal practice and training delivery experiences.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics were assessed only at baseline. The information collected included age, gender, educational level, major, marital status, and religious belief.

Five Facet of Mindfulness Questionnaire

Mindfulness was assessed using the Five Facet of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2008). The FFMQ consists of 39 items with 5 subscales: Observing (8 items, example is “When I take a shower or bath, I stay alert to the sensations of water on my body”), describing (8 items, example is “I can easily put my beliefs, opinions, and expectations into words”), acting with awareness (8 items, example is “I don’t pay attention to what I’m doing because I’m daydreaming, worrying, or otherwise distracted”), nonjudging of inner experience (8 items, example is “I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way I’m feeling”), and nonreactivity to inner experience (7 items, example is “I watch my feelings without getting lost in them”). The Chinese version of FFMQ was applied in the current study. The total scores of the FFMQ range between 39 and 195, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mindfulness. The scale has demonstrated adequate to good internal consistency for all five facets and is robust for different types of samples (Baer et al., 2006, 2008). The Chinese version of FFMQ has been demonstrated with good reliability and validity among college students (Li et al., 2017). The inter-item consistency and reliability of the whole scale in the present study were 0.85 of Cronbach’s alpha and 0.84 of McDonald’s omega, respectively.

Learning Burnout of University Students

Learning burnout was measured by the Learning Burnout of University Student (LBUS; Lian, 2005). It was developed based on the three dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory and revised in the context of China. It is a 20-item scale which consists of 3 subscales: emotional exhaustion (8 items), improper behavior (6 items), and reduced personal accomplishment (6 items). Emotional exhaustion refers to the difficulty of handling the problems and requests of study. An example item is “It is difficult for me to maintain a long-term passion for learning”. Improper behavior refers to the characteristics that students show due to the tiredness of study, for example “I seldom study after class”. Reduced personal accomplishment refers to the feeling of incapacity during the study process, for example “It’s easy for me to master professional knowledge”. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale demonstrated good inter-item consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89, McDonald’s omega = 0.90).

Data Analyses

SPSS version 26.0 was used to perform data analyses. Firstly, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess common method bias. Then, differences between the intervention and control groups regarding demographic characteristics were examined with independent samples t-tests and chi-square examinations. Multivariate repeated measures analyses (MANOVAs) were performed to examine the intervention effect on mindfulness and burnout based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) approach (Little & Yau, 1996). Missing data were checked as missing at random using the methods recommended by Sun et al. (2013) and were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method (Heyting et al., 1992). Typically, two decimal places were adopted. In some circumstances, such as goodness-of-fit indices where cut-off values were very small (e.g., 0.002 for partial η2), three decimal places were used. All analyses were performed two-sided and statistical significance was declared at p < 0.05.

Bivariate correlations based on all participants were computed between changes in mindfulness and burnout. For mediation analysis, the PROCESS macro for SPSS was performed (Hayes, 2013). Mediation effect of mindfulness was analyzed under the simple mediation model (Model 4) with 5000 bootstrap samples. Simple mediation analysis was run with the variable of group as the predictor and changes in burnout (pre-intervention to 3-month follow-up) and mindfulness (pre-intervention to post-intervention) as the outcome and mediator, respectively. The indirect effect was considered significant when the upper and lower limits of CIs did not contain zero. This approach is more powerful than the Sobel test as it does not rely on the assumption of a normal sampling distribution (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017).

Results

Common Method Bias

Harman’s single-factor test showed that eigenvalues of 17 factors were greater than 1. The amount of variance explained by the first factor was 26.87%, which was less than the threshold of 40%, indicating no significant common method bias existed in the study.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Results of t-tests and chi-square analyses indicated that there were no significant differences between the participants dropped out versus those who completed the study on demographic variables and dependent variables measured at baseline. Participants’ characteristics are documented in Table 1. The sample age ranged from 17 to 30 years old (M = 21.36 years, SD = 2.76 years) and 68.75% were females (88 females, 40 males). More than half of the students were undergraduates (57.00%). Almost all students were single (99.20%) and did not have a religious belief (96.90%). There were no significant differences between the intervention group and control group regarding age (t(126) = 0.14, p = 0.89), gender (\({\chi }^{2}\)(1) = 0.15, p = 0.70), educational level (\({\chi }^{2}\)(2) = 0.04, p = 0.98), major (\({\chi }^{2}\)(5) = 6.61, p = 0.25), marital status (\({\chi }^{2}\)(1) = 1.01, p = 0.32), and religious belief (\({\chi }^{2}\)(1) = 0.00, p = 1.00). In addition, no differences were found in any of the psychological outcome variables, namely mindfulness (t(126) = 0.96, p = 0.34) and burnout (t(126) = 0.62, p = 0.54), indicating that the randomization was successful.

Intervention Effects on Mindfulness and Burnout

Table 2, Fig. 2, and Fig. 3 demonstrate the results of the intervention. A significant main effect of time was found on mindfulness from pre-intervention to post-intervention (F = 37.94, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.23) and 3-month follow-up (F = 40.95, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.26) for both groups. In addition, a significant interaction of time × group emerged both at post-intervention (F = 22.41, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.15) and 3-month follow-up (F = 16.29, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.12), indicating that the intervention group reported a larger improvement of mindfulness than the control group.

The intervention group showed significantly greater reductions in burnout both at post-intervention and 3-month follow-up compared with pre-intervention than the control group. ITT analysis indicated no main effect of group neither at post-intervention (F = 0.26, p = 0.61, partial η2 = 0.002) nor 3-month follow-up (F = 0.47, p = 0.49, partial η2 = 0.004), a significant effect of time both at post-intervention (F = 24.02, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.16) and 3-month follow-up (F = 10.37, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.08), and a significant time × group interaction both at post-intervention (F = 8.24, p = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.06) and 3-month follow-up (F = 9.24, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.07).

Mediation Effect of Mindfulness

The analysis showed a significant indirect effect of the training on burnout through changes in mindfulness, and the mediation effect was full (Table 3 and Fig. 4). The effect of mediators on independent variable was 10.89 (p < 0.01, 95%CI [6.34, 15.44]), and the effect of outcome variable on mediator was − 0.03 (p < 0.01, 95%CI [− 0.45, − 0.21]).

Mediation model for the effect of group on change in burnout. a The direct effect of group on change in burnout. b The mediation model with the indirect effect of group via change in mindfulness on change in burnout, decreasing the direct effect of group on change in burnout, indicating full mediation. Note. Non-standardized beta coefficients were adopted in the current study

Discussion

Though numerous studies have linked MBIs with various health outcomes, the associations between these kinds of interventions and burnout in college students remain an under-researched area. Meanwhile, studies exploring the potential effect of MBIs on burnout among college students yielded mixed results, and the mechanisms of the interventions need to be better understood. This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based training program on the reduction of burnout among Chinese college students, and explore the underlying mechanism. Significant decreases in burnout were found both at post-intervention and 3-month follow-up for the intervention group compared with the control group, indicating that an 8-week mindfulness training program could well alleviate the level of students’ burnout. In addition, changes in mindfulness were found to fully mediate the process, demonstrating that the effect of the program on burnout was through the improvement of mindfulness. To our best knowledge, it is one of the few studies testing the effectiveness of MBIs on burnout among college students in China. The study adds evidences to this area, and is supposed to promote the application and dissemination of MBIs in this young population in the future.

We found that participants in the intervention group showed a greater decrease in burnout than those in the control group. Our findings provided evidence for the feasibility of using MBI programs to reduce burnout among college students. Reduction in burnout as a result of a MBI program for college students has been reported previously in a nonrandomized study (Garneau et al., 2013), though non-significant results were also found in other randomized or nonrandomized studies (Barbosa et al., 2013; de Vibe et al., 2013; Oro et al., 2021). Possible explanations for these results may be due to the small sample sizes (Barbosa et al., 2013), specific sample composition (Oro et al., 2021), and gender differences (de Vibe et al., 2013). Specially, in the experiment conducted by Barbosa et al. (2013), only 13 students were recruited for the MBSR program with being compared to 15 controls, which made the findings less reliable. Apart from small sample sizes, specific sample composition may also be a factor that leads to no observed effect. In the study of Ole et al. (2021), only medical students were chosen as the participant sample. Medical student population was a special subgroup of students who undertake massive courses and tasks to become qualified medical professionals (Dyrbye & Shanafelt, 2016; Ishak et al., 2013). Therefore, their burnout may not be easily reduced through eight sessions of a regular mindfulness-based program. Another factor that should be taken into consideration is gender difference. In the research by de Vibe et al. (2013), though no impact was found on males, females demonstrated an expected tendency on the alleviation of burnout. Gender-specific differences should be considered in future studies.

Another important contribution of the present work was that it examined the mediating effect of mindfulness level on burnout which, to our knowledge, has not been demonstrated in previous studies in college student population. In our study, the intervention group showed a larger increase in mindfulness than the control group. We also found that the changes in mindfulness during the intervention fully mediated the intervention effect on burnout. These results suggested that the MBI program did take effects on burnout through increasing mindfulness level.

The mediation effect of mindfulness has been indicated in some studies conducted in the population of teachers and burnout employees (Kinnunen et al., 2020; Roeser et al., 2013). The trials conducted in 113 school teachers showed significant mediation effect of mindfulness level on teachers’ symptoms of occupational burnout, with the direct effect being significant as well (Roeser et al., 2013). The model built among a total of 202 heterogeneous sample of employees suffering from burnout also demonstrated that the improvement of mindfulness during the intervention mediated burnout reduction during both the intervention and the 10-month follow-up, with different mindfulness facets mediated changes in different burnout dimensions (Kinnunen et al., 2020). Our results provided evidences to the above mechanism of mindfulness training in the student population.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study showed promising results, there existed several limitations. First, our recruitment procedure may have partially attracted a subset of college students interested in this form of intervention, limiting the generalizability to the general student population. Another potential limitation was the control design. It would give stronger support for the specific effects of the MBI program when an active control intervention was adopted. Nonetheless, measures were taken to examine the mediation effect of mindfulness during the intervention, and the results indicated that the intervention was taking effect through the improvement of mindfulness, which we believe refuted the hypothesis of placebo effect to a certain extent.

In a word, the present study gives an indication that the reduction in burnout resulting from a MBI program can be explained by increased level of mindfulness. This supports the use of a MBI program to alleviate burnout among college students and suggests a causal pathway in which the MBI program influences burnout. Future research should focus on understanding the potential mechanism that links mindfulness and burnout.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Al-Alawi, M., Al-Sinawi, H., Al-Qubtan, A., Al-Lawati, J., Al-Habsi, A., Al-Shuraiqi, M., Al-Adawi, S., & Panchatcharam, S. M. (2019). Prevalence and determinants of burnout syndrome and depression among medical students at Sultan Qaboos University: A cross-sectional analytical study from Oman. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 74(3), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2017.1400941

Almeida, G. d. C., de Souza, H. R., de Almeida, P. C., Almeida, B. d. C., & Almeida, G. H. (2016). The prevalence of burnout syndrome in medical students. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry, 43(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-60830000000072

Appelbaum, N. P., Lee, N., Amendola, M., Dodson, K., & Kaplan, B. (2019). Surgical resident burnout and job satisfaction: The role of workplace climate and perceived support. Journal of Surgical Research, 234, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.08.035

Appels, A., & Schouten, E. (1991). Burnout as a risk factor for coronary heart-disease. Behavioral Medicine, 17(2), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.1991.9935158

Armon, G., Melamed, S., Shirom, A., & Shapira, I. (2010). Elevated burnout predicts the onset of musculoskeletal pain among apparently healthy employees. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020726

Atalayin, C., Balkis, M., Tezel, H., Onal, B., & Kayrak, G. (2015). The prevalence and consequences of burnout on a group of preclinical dental students. European Journal of Dentistry, 9(3), 356–363. https://doi.org/10.4103/1305-7456.163227

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bpg015

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., Walsh, E., Duggan, D., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003

Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job demands-resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 34(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695

Barbosa, P., Raymond, G., Zlotnick, C., Wilk, J., Toomey, R., 3rd., & Mitchell, J., 3rd. (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction training is associated with greater empathy and reduced anxiety for graduate healthcare students. Education for Health, 26(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.112794

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bph077

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Capri, B., Ozkendir, O. M., Ozkurt, B., & Karakus, F. (2012). General self-efficacy beliefs, life satisfaction and burnout of university students. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 47, 968–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.76

Chang, E., Eddins-Folensbee, F., & Coverdale, J. (2012). Survey of the prevalence of burnout, stress, depression, and the use of supports by medical students at one school. Academic Psychiatry, 36(3), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.11040079

Cook, A. F., Arora, V. M., Rasinski, K. A., Curlin, F. A., & Yoon, J. D. (2014). The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Academic Medicine, 89(5), 749–754. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000204

Dahlin, M., Joneborg, N., & Runeson, B. (2007). Performance-based self-esteem and burnout in a cross-sectional study of medical students. Medical Teacher, 29(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590601175309

Davies, J. N., Sharpe, L., Day, M. A., & Colagiuri, B. (2021). Mindfulness-based analgesia or placebo effect? The development and evaluation of a sham mindfulness intervention for acute experimental pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 83(6), 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000000886

de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Tyssen, R., Friborg, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., Sorlie, T., & Bjorndal, A. (2013). Mindfulness training for stress management: A randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Medical Education, 13, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-107

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.499

dos Santos Boni, R. A., Paiva, C. E., de Oliveira, M. A., Lucchetti, G., Tavares Guerreiro Fregnani, J. H., & Ribeiro Paiva, B. S. (2018). Burnout among medical students during the first years of undergraduate school: Prevalence and associated factors. PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0191746. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191746

Dyrbye, L., & Shanafelt, T. (2016). A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Medical Education, 50(1), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12927

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., Massie, F. S., Power, D. V., Eacker, A., Harper, W., Durning, S., Moutier, C., Szydlo, D. W., Novotny, P. J., Sloan, J. A., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2008). Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149(5), 334-W370. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008

Fendel, J. C., Burkle, J. J., & Goritz, A. S. (2021). Mindfulness-based interventions to reduce burnout and stress in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine, 96(5), 751–764. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003936

Fitzpatrick, O., Biesma, R., Conroy, R. M., & McGarvey, A. (2019). Prevalence and relationship between burnout and depression in our future doctors: A cross-sectional study in a cohort of preclinical and clinical medical students in Ireland. BMJ Open, 9(4), e023297. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023297

Flook, L., Goldberg, S. B., Pinger, L., Bonus, K., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Mindfulness for teachers: A pilot study to assess effects on stress, burnout, and teaching efficacy. Mind Brain and Education, 7(3), 182–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12026

Garneau, K., Hutchinson, T. A., Zhao, Q., Dobkin, P. L. J. E. J., & f. P. C. H. (2013). Cultivating person-centered medicine in future physicians. European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare, 1, 468–477. https://doi.org/10.5750/EJPCH.V1I2.688

Green, A. A., & Kinchen, E. V. (2021). The effects of mindfulness meditation on stress and burnout in nurses. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 39(4), 356–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/08980101211015818

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work and Stress, 22(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802379432

Harker, R., Pidgeon, A. M., Klaassen, F., & King, S. (2016). Exploring resilience and mindfulness as preventative factors for psychological distress burnout and secondary traumatic stress among human service professionals. Work, 54(3), 631–637. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-162311

Hathaisaard, C., Wannarit, K., & Pattanaseri, K. (2022). Mindfulness-based interventions reducing and preventing stress and burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 69, 102997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102997

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001

Heyting, A., Tolboom, J. T. B. M., & Essers, J. G. A. (1992). Statistical handling of drop-outs in longitudinal clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine, 11(16), 2043–2061. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780111603

Hu, Q., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey in China. Psychological Reports, 105(2), 394–408. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.105.2.394-408

Ishak, W., Nikravesh, R., Lederer, S., Perry, R., Ogunyemi, D., & Bernstein, C. (2013). Burnout in medical students: A systematic review. The Clinical Teacher, 10(4), 242–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12014

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation - Theoretical considerations and preliminary - Results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bpg016

Kemper, K. J., McClafferty, H., Wilson, P. M., Serwint, J. R., Batra, M., Mahan, J. D., Schubert, C. J., Staples, B. B., Schwartz, A., & Pediat Resident, B.-R. (2019). Do mindfulness and self-compassion predict burnout in pediatric residents? Academic Medicine, 94(6), 876–884. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002546

Kinnunen, S. M., Puolakanaho, A., Tolvanen, A., Makikangas, A., & Lappalainen, R. (2020). Improvements in mindfulness facets mediate the alleviation of burnout dimensions. Mindfulness, 11(12), 2779–2792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01490-8

Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., & Georganta, K. (2019). The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284

Langballe, E. M., Innstrand, S. T., Hagtvet, K. A., Falkum, E., & Aasland, O. G. (2009). The relationship between burnout and musculoskeletal pain in seven Norwegian occupational groups. Work, 32(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-2009-0804

Lee, K. P., Yeung, N., Wong, C., Yip, B., Luk, L. H. F., & Wong, S. (2020). Prevalence of medical students’ burnout and its associated demographics and lifestyle factors in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE, 15(7), e0235154. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235154

Li, C. X., Zhu, Y. X., Zhang, M. G., Gustafsson, H., & Chen, T. (2019). Mindfulness and athlete burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030449

Li, X., Wuyuntena, Yuan, F.-z., Liu, Z.-h., & Fan, L.-l. (2017). A analysis of reliability and validity of FFMQ by clasical test theory and the generalizability theory. Journal of Inner Mongolia Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 46(05), 776–780.

Lian, R. Y. L. W. L. (2005). Relationship between professional commitment and learning burnout of undergraduates and scales developing. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 37(05), 632.

Little, R., & Yau, L. (1996). Intent-to-treat analysis for longitudinal studies with drop-outs. Biometrics, 52(4), 1324–1333. https://doi.org/10.2307/2532847

Liu, W., Zhao, S., Shi, L., Zhang, Z., Liu, X., Li, L., Duan, X., Li, G., Lou, F., Jia, X., Fan, L., Sun, T., & Ni, X. (2018). Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 8(6), e019525. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019525

Luken, M., & Sammons, A. (2016). Systematic review of mindfulness practice for reducing job burnout. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(2), 7002250020p1–7002250020p10. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.016956

Mafla, A. C., Villa-Torres, L., Polychronopoulou, A., Polanco, H., Moreno-Juvinao, V., Parra-Galvis, D., Duran, C., Villalobos, M. J., & Divaris, K. (2015). Burnout prevalence and correlates amongst Colombian dental students: The STRESSCODE study. European Journal of Dental Education, 19(4), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12128

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Mazurkiewicz, R., Korenstein, D., Fallar, R., & Ripp, J. (2012). The prevalence and correlations of medical student burnout in the pre-clinical years: A cross-sectional study. Psychology Health & Medicine, 17(2), 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2011.597770

Melamed, S. (2009). Burnout and risk of regional musculoskeletal pain-a prospective study of apparently healthy employed adults. Stress and Health, 25(4), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1265

Noone, C., & Hogan, M. J. (2018). A randomised active-controlled trial to examine the effects of an online mindfulness intervention on executive control, critical thinking and key thinking dispositions in a university student sample. BMC Psychology, 6(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0226-3

Oro, P., Esquerda, M., Mas, B., Vinas, J., Yuguero, O., & Pifarre, J. (2021). Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based programme on perceived stress, psychopathological symptomatology and burnout in medical students. Mindfulness, 12(5), 1138–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01582-5

Pagnin, D., de Queiroz, V., Carvalho, Y., Dutra, A. S. S., Amaral, M. B., & Queiroz, T. T. (2014). The relation between burnout and sleep disorders in medical students. Academic Psychiatry, 38(4), 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0093-z

Rahmati, Z. (2015). The study of academic burnout in students with high and low level of self-efficacy. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 171, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.087

Roeser, R. W., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Jha, A., Cullen, M., Wallace, L., Wilensky, R., Oberle, E., Thomson, K., Taylor, C., & Harrison, J. (2013). Mindfulness training and reductions in teacher stress and burnout: Results from two randomized, waitlist-control field trials. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 787–804. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032093

Salvado, M., Marques, D. L., Pires, I. M., & Silva, N. M. (2021). Mindfulness-based interventions to reduce burnout in primary healthcare professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare, 9(10), 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101342

Salvarani, V., Rampoldi, G., Ardenghi, S., Bani, M., Blasi, P., Ausili, D., Di Mauro, S., & Strepparava, M. G. (2019). Protecting emergency room nurses from burnout: The role of dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation and empathy. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(4), 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12771

Santen, S. A., Holt, D. B., Kemp, J. D., & Hemphill, R. R. (2010). Burnout in medical students: Examining the prevalence and associated factors. Southern Medical Journal, 103(8), 758–763. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e6d6d4

Scanlan, J. N., & Still, M. (2019). Relationships between burnout, turnover intention, job satisfaction, job demands and job resources for mental health personnel in an Australian mental health service. Bmc Health Services Research, 19, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3841-z

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students - A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003

Schutte, N., Toppinen, S., Kalimo, R., & Schaufeli, W. (2000). The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) across occupational groups and nations. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900166877

Suleiman-Martos, N., Gomez-Urquiza, J. L., Aguayo-Estremera, R., Canadas-De La Fuente, G. A., De La Fuente-Solana, E. I., & Albendin-Garcia, L. (2020). The effect of mindfulness training on burnout syndrome in nursing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(5), 1124–1140. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14318

Sun, J., Jin, Y., & Dai, M. (2013). Discussion on testing the mechanism of missing data. Mathematics in Practice and Theory, 43(12), 166–173.

Taylor, N. Z., & Millear, P. M. R. (2016). The contribution of mindfulness to predicting burnout in the workplace. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.005

Toker, S., Melamed, S., Berliner, S., Zeltser, D., & Shapira, I. (2012). Burnout and risk of coronary heart disease: A prospective study of 8838 employees. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(8), 840–847. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31826c3174

Toppinen-Tanner, S., Ahola, K., Koskinen, A., & Vaananen, A. (2009). Burnout predicts hospitalization for mental and cardiovascular disorders: 10-year prospective results from industrial sector. Stress and Health, 25(4), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1282

Van der Heijden, B., Mahoney, C. B., & Xu, Y. (2019). Impact of job demands and resources on nurses’ burnout and occupational turnover intention towards an age-moderated mediation model for the nursing profession. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(11), 2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16112011

Vela-Bueno, A., Moreno-Jimenez, B., Rodriguez-Munoz, A., Olavarrieta-Bernardino, S., Fernandez-Mendoza, J., Jose De la Cruz-Troca, J., Bixler, E. O., & Vgontzas, A. N. (2008). Insomnia and sleep quality among primary care physicians with low and high burnout levels. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 64(4), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.014

Vidhukumar, K., & Hamza, M. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of burnout among undergraduate medical students - A cross-sectional survey. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 42(2), 122–127. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpsym.Ijpsym_192_19

Vilardaga, R., Luoma, J. B., Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., Levin, M. E., Hildebrandt, M. J., Kohlenberg, B., Roget, N. A., & Bond, F. (2011). Burnout among the addiction counseling workforce: The differential roles of mindfulness and values-based processes and work-site factors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 40(4), 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2010.11.015

Yang, H. J. (2004). Factors affecting student burnout and academic achievement in multiple enrollment programs in Taiwan’s technical-vocational colleges. International Journal of Educational Development, 24(3), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2003.12.001

Zhu, T., Xue, J., Montuclard, A., Jiang, Y., Weng, W., & Chen, S. (2019). Can mindfulness-based training improve positive emotion and cognitive ability in Chinese non-clinical population? A Pilot Study. Front Psychol, 10, 1549. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01549

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Grant Number GF21C090006) and the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (Grant Number 22YJCZH209).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruochen Gan: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, project administration, formal analysis, writing — original draft. Jiang Xue: writing — review and editing. Shulin Chen: funding acquisition, writing — review and editing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Zhejiang University (No. [2021]027).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gan, R., Xue, J. & Chen, S. Do Mindfulness-Based Interventions Reduce Burnout of College Students in China? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 14, 880–890 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02092-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02092-w