Abstract

Objectives

Training in mindfulness has been found to enhance interpersonal benefits (e.g., gratitude, forgiveness, empathy, compassion). Here, we ask if these interpersonal benefits extend to intergroup contexts.

Methods

Two experiments (n = 256) tested whether brief mindfulness instruction predicted higher prosocial helping behavior toward an ostracized racial outgroup member.

Results

In Study 1, mindfulness instruction, relative to active and inactive controls, predicted higher helping behavior toward an ostracized racial outgroup member in a private (but not in a public) context. State empathic concern did not mediate the relationship between mindfulness training and private helping behavior. In Study 2, which involved greater anonymity, mindfulness instruction predicted higher private and public helping behavior toward an ostracized racial outgroup member. Empathic concern statistically mediated the relationship between mindfulness training and public, but not private, helping.

Conclusions

Together these two studies indicate that, in a relatively anonymous context, brief mindfulness instruction predicts higher empathic concern and helping behavior toward an ostracized racial outgroup member. Discussion focuses on implications and limitations of mindfulness for intergroup prosociality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness has been described as a sustained receptive attention to present-moment experiences (Anālayo, 2020; Quaglia, et al., 2015). Although most scientific inquiry on mindfulness has focused on its correlates with mental and physical health and well-being (e.g., Howarth et al., 2019), research literature on its relevance to wholesome social outgrowths (e.g., compassion, kindness) has been growing in recent years (see Karremans & Papies, 2017 for review). Theories about the benefits of contemplative practice affirm the value of mindfulness and related forms of meditation practice for catalyzing virtuous action (e.g., Davidson & Harrington, 2002), not least for its potential to foster prosociality (see Schindler & Friese, 2022 for review)—defined as cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses intended to promote others’ well-being (Tomasello, 2009). In particular, brief mindfulness trainings, relative to waitlist controls and active control trainings, have been shown to promote prosocial emotions and/or behavior (e.g., Berry et al., 2020; Donald et al., 2019).

In three recent experiments, Berry et al. (2018) found that mindfulness trainees, relative to attention-based, relaxation, and inactive controls, wrote comparatively more comforting emails to ostracized strangers (also see Tan et al., 2014) and included them more in an online game. Berry et al. (2018) extended previous work on the role of mindfulness in prosociality in two ways. First, empathic concern, a key proximal promoter of helping behavior, and an emotion that entails caring for an affected person (Batson, 2009), mediated the effect of brief mindfulness instructions on helping behavior (Berry et al., 2018). Conversely, the self-oriented emotions of empathic anger and empathic distress did not mediate this effect—important because these are much less likely to lead to prosocial action. Second, in the Berry et al. (2018) studies, the target of mindfulness participants’ empathic concern and helping behavior was a stranger. This finding is also important, as a lack of familiarity with an affected person is a common cognitive division between self and others that reduces prosociality (e.g., Kurzban et al., 2015).

It is important to ask whether mindfulness would foster empathic concern and prosocial action in a social context marked by an arguably more serious social division: that based on race. Racial outgroup members, just like strangers, are often shown less empathy and given less help when in need relative to racial ingroup members (e.g., Cikara et al., 2011; Saucier, 2015). Efforts have been made to promote interracial empathic concern, commonly through the study of various forms of perspective taking (role playing, simulation, intergroup contact; Batson & Ahmad, 2009). Perspective taking manipulations commonly involve imagining how a victim feels, and these exercises can readily promote empathic concern and prosocial behavior toward racial (and other social) outgroups (Batson et al., 1997; Dovidio et al., 2010; Vescio et al., 2003). However, more recent research has found that perspective taking and other explicit appeals to increase interracial prosociality can fall short in two ways (see Zaki & Cikara, 2015 for review). First, outgroup members’ mental complexity is often misunderstood or neglected, both of which may promote reliance on stereotypes about their traits, goals, intentions, emotions, and behaviors (Enock et al., 2021; Leyens et al., 2000; Park & Judd, 1990; Rothbart & Taylor, 1992). Incomplete understanding of outgroup members’ experiences and predicaments may inhibit our ability to take racial outgroup members’ perspectives. Second, perspective taking may also be difficult to implement when there is pre-existing antipathy toward the outgroup (Galinsky et al., 2005).

Theorists have long hypothesized that mindfulness and other contemplative mind states may enhance prosociality by lowering perceived boundaries between self and others (e.g., DeSteno, 2015). In line with this theorizing, training in mindfulness has been associated with altered patterns of connectivity in the brain’s default mode network (DMN; Brewer et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2013), thought to reflect a reduction in the habitual, self-oriented thought patterns associated with DMN activity (Christoff et al., 2009). Mindfulness training has also been associated with reduced activity in the medial prefrontal cortex, a region associated with self-referential processing, and enhanced activity in visceromotor regions (e.g., anterior insula) during mindfulness meditation (Farb et al., 2007), which appear to be involved in generating empathic distress (e.g., Ashar et al., 2017). Self-oriented thought patterns are typically very accessible (e.g., Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010), and these cognitions help to support conceptual boundaries between self and others that can hinder empathic concern (Fennis, 2011).

Two phenomenological features of mindfulness (Brown & Cordon, 2009) are relevant to interracial prosociality: First, experience of what is occurring in the present becomes of paramount interest, whether that experience arises from within the body-mind or through the senses. Second, this “presence” is entered through a suspension of the habitual or automatized ways of processing experience through memories, conditioned appraisals, and so on in favor of a receptive attentiveness that simply processes what is occurring moment by moment. Consistent with this, Lueke and Gibson (2015) found that, among self-identifying White individuals, brief training in mindfulness, relative to a narrative control, predicted lower implicit race bias toward Black individuals. Follow-up analyses indicated that mindfulness reduced implicit bias because of subdued automatic activation of conditioned Black/bad associations. Brief instruction in mindfulness has also been associated with less racial discrimination in trust behaviors (Lueke & Gibson, 2016). These findings are especially relevant given that harboring higher implicit biases against racial outgroup members is associated with lower empathy (e.g., Gutsell & Inzlicht, 2012) and willingness to help outgroup members (Gaertner et al., 1982; Kunstman & Plant, 2008).

This research is promising, but it is difficult to ascribe prosocial emotion to these behaviors, as it is possible that individuals offer help in intergroup interactions to patronize (Vescio et al., 2003) and/or to maintain social dominance over that group (Nadler, 2002). This represents an important avenue toward better understanding the self-or-other-oriented emotional bases of prosocial responsiveness in interracial contexts, and because mindfulness can be trained (Quaglia et al., 2015), such research may have implications for tailoring interventions to enhance interracial prosociality.

We conducted two experiments that tested whether brief mindfulness instruction would promote prosocial behavior toward an ostracized racial outgroup member. These studies also aimed to understand whether mindfulness promotes interracial prosociality in an ostracism context through other-oriented empathic concern. Ostracism entails ignoring or excluding another person; it is psychologically painful for its victims, and witnessing ostracism can provoke personal distress or empathic concern for and helping behavior toward its victim (Beeney et al., 2011; Masten et al., 2011), especially when the victim is perceived as similar to oneself (Beeney et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2013). However, studies uncovering intrapsychic factors that foster helping behavior toward ostracism victims—along with social cues like race that constrain prosociality—are few.

We asked whether brief instruction in mindfulness would increase empathic concern for and helping behavior toward ostracized racial outgroup members. Furthermore, because empathic concern is a known state-level predictor of both perceived closeness and autonomous prosocial helping, we expected that empathic concern, but not empathic distress or empathic anger, would mediate the effect of mindfulness on helping outgroup members. In two studies, self-identifying White participants were randomized to either (a) a brief mindfulness exercise; (b) a structurally equivalent attention-based control exercise; or (c) a no-instruction control condition prior to observing an online ball-tossing game in which a “player” is excluded (Cyberball; Williams et al., 2012). Study 1 participants witnessed the ostracism of a Black individual indicated by a photographic image (Minear & Park, 2004). Study 2 participants also witnessed a Black individual being ostracized, but race was indicated using a stereotypically Black- or African American–sounding name (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004). In both studies, state empathic concern, empathic distress, and empathic anger were measured after witnessing game exclusion to test that empathic concern alone would mediate the mindfulness–helping relation. Thereafter, two forms of objective helping behavior toward the ostracism victim were measured.

To date, few studies have examined whether any form of mindfulness training promotes prosocial responsiveness toward racial outgroup members (Berry et al., 2021; Lueke & Gibson, 2016). Several design characteristics were included to enhance the strength of this test. First, the studies used one active, structurally equivalent control condition. Second, the interventions were facilitated via audio recording, removing biases that could be introduced by live facilitators. These two study characteristics serve as important extensions of research on mindfulness in prosociality, as recent meta-analyses showed that mindfulness interventions promote prosociality only when pitted against inactive controls and when intervention facilitators are included as co-authors on the article (Kreplin et al., 2018).

Third, perceived social status of the ostracism victim was measured in Study 2 to help rule out the possibility that socioeconomic status perceptions were a predictor of empathy and helping. Fourth, the explicit intentions to include and exclude other (non-ostracized) players during the “all play” game were measured to rule out the possibility that participants wanted to punish the ostracism perpetrators rather than help the ostracism victim (Berry et al., 2018).

Fifth, only a focused attention form of mindfulness instruction was used in these studies to specify the type of training received (Lutz et al., 2015). Mindfulness instruction can take a variety of forms, and limiting the type received helps to advance our understanding of the effects of specific forms. Finally, the mindfulness instructions did not include content that could explicitly conduce to empathy or helping.

Study 1

Study 1 tested three hypotheses derived from theory and previous research: Brief instruction in mindfulness, relative to both active and inactive control conditions, will increase empathic concern for (Hypothesis 1) and helping of (Hypothesis 2) an ostracized racial outgroup member. Mindfulness instruction will promote helping behavior via increases in empathic concern (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Sample Size Determination

An a priori sample size of n = 108 (n = 36 per condition) was set as per the experiments by Berry et al., (2018) testing the effects of brief mindfulness instruction on helping behavior responses to ostracism victims. Specifically, Berry and colleagues (2018) found moderate effect sizes of mindfulness instruction on helping behavior toward ostracism victims (d = 0.60), and we determined sample size based on this effect size estimate in G*Power 3.0.10 (α = 0.05, power = 0.80). Suspicious participants and careless responders were expected and were to be excluded from analyses. We, therefore, planned to over-recruit participants past the minimum sample size required until the end of the semester (n = 162).

Participants

In February 2015, 162 self-identifying White undergraduates from a Mid-Atlantic US university received course credit for participation. Seventeen people indicated suspicion about the study cover story about studying social interaction over the Internet and were excluded from analyses; one participant was excluded for careless responses, making errors on directed questions (e.g., “This is a control question, please skip this question;” Meade & Craig, 2012). Twenty participants were additionally excluded from analyses due to experimenter error in uploading participants’ photographic images into the Cyberball environment. The remaining 124 participants were 64.52% female, with an average age of 20.81 years (SD = 4.38). In this study and the one that follows, there was a different proportion of missing data across study outcomes (Table 1).

Procedure

The procedure largely replicated that used in the Berry et al. (2018) experiments. Participants were tested individually in a single laboratory room. Prior to observing an ostensible ostracism scenario, a basic form of trait mindfulness (Brown & Ryan, 2003) was measured and then photographic profile images of participants were taken using a digital camera and were uploaded by an experimenter into the Cyberball environment. Using serial random assignment (https://www.randomizer.org/), participants were then assigned to one of three audio instruction groups: mindfulness-based audio instructions (MI; n = 48), attention-based audio instructions (AI; n = 36), or no instruction (NI; n = 40). Experimenters were masked to condition until the start of the audio recording.

Participants in the MI and AI conditions listened to an 8 min 35 s audio-recorded instructional tape through headphones. The MI involved a series of instructions, delivered by a male voice, that oriented participants to specific dynamic inner experiences (Lutz et al., 2015), namely moment-to-moment somatic, cognitive, and emotional stimuli (adapted from Segal et al., 2002). Additionally, the MI instructed participants in meta-cognitive awareness—noticing when one’s mind had wandered and returning to the task. The AI, of the same length and also delivered by a male voice, highlighted the importance of focusing attention on important and urgent goals (adapted from Covey et al., 1995). The AI helped to isolate a mindful quality of attention as it lacked components of meta-cognitive awareness and moment-to-moment assiduity. Because mindfulness and its training are correlated with momentary attentional focus (Chin et al., 2021), and that attentional control has predicted empathy and helping (Dickert & Slovic, 2009), the focus on attention to goals in the AI condition was important for experimentally isolating a mindful quality of attention in prosocial responsiveness. NI participants were told to “take a few moments to become actively engaged on your own” prior to observing the Cyberball game. Although there was an analogous preparatory period, in contrast to the audio instructions, which guided the participants in one or another cognitive exercise, the “no instruction” control was distinct in the fact that there were no instructions or guidance provided by the researchers to the participants. The NI allowed greater precision in inferring that it was MI increasing empathic concern and prosocial responsiveness rather than AI lowering scores on these outcomes. The mindfulness-based and attention-based instructions were based on those by Berry et al. (2018), which had been adapted from Brown et al. (2016).

To provide a cover story to link these audio (and no-) instructions with the social interaction tasks, participants were told that the “study is about the role of active engagement in social interaction over the Internet.” Importantly, instructions before and during the trainings made no mention of empathy-related or helping-related ideas, nor did they mention the contents of the tasks to follow.

Participants were also told that their unique study identification number pre-assigned them to first observe an online ball-tossing game (Cyberball version 4.0; Williams et al., 2012), and they would join an “all play” game thereafter. During the first, observed game, one player was excluded from the ball tossing. The ostracism victim was a Black individual and the other players (perpetrators) were one White and one Black individual, identified using photographic images obtained from an open database (Minear & Park, 2004). Although participants were led to believe, via a sham phone call, that the other players in this game were fellow students joining from other labs on campus, these ostensible players and their throws were software generated.

Immediately after the observed game, participants were queried as to whether exclusion occurred and about the racial demographics of the other players; six questions were administered to rule out the possibility that aspects of the experimenter-delivered instructions and/or audio recordings explained experimental condition differences in study outcomes. State empathic concern, empathic distress (Batson et al., 1987), and empathic anger (Vitaglione & Barnett, 2003) were then measured. To conceal study aims and preserve experimental realism, state empathy measures did not specify an empathy target. Thereafter, participants wrote an email to each ostensible player using a real email (Gmail) account. They were told that “email is one type of social interaction over the Internet” and that they were to “write an email to each of the other players.” Instructions stated that there were no word minimums to be adhered to in the emails and that participants could write about whatever they wanted. If participants asked what they were supposed to write about, they were reminded that they “could write about whatever they wanted, but most people wrote about the ball-tossing game.” Responses to the victim, coded by four hypothesis-naïve raters for prosociality (Masten et al., 2011), served as a first measure of helping behavior.

During a following “all-play” Cyberball game with the three players observed earlier, inclusion of the ostracism victim, a second indicator of helping behavior, was measured as the proportion of the total throws that the participant made to the victim (Riem et al., 2013). Just prior to joining the “all-play” game, participants listened to a brief, 2-min booster instruction consistent with their experimental condition (Berry et al., 2018). Following this second game, three items were administered assessing participants’ intention to include or exclude each of the other three players. Trait empathy (Davis, 1983), racism (Henry & Sears, 2002), and political attitudes (Sargent, 2004) were measured thereafter so as not to create an experimental demand. Political attitudes were measured with a single item: “When it comes to politics, where would you place yourself on the following continuum?” Responses were made on a 7-point Likert-type scale (extremely liberal to extremely conservative). After a post-experimental inquiry that assessed suspicion about the study, participants were debriefed, thanked, and dismissed.

Measures

Trait Mindfulness

The 15-item Mindful Attention Awareness Scale measured the frequency to which participants abided in mindful states on a 6-point Likert-type scale (almost always to almost never) (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Higher scores indicate higher frequencies of mindfulness in daily life (sample α = 0.90).

Trait Empathy

Four sub-scales (seven items each) of the Interpersonal Reactivity Inventory (fantasy, empathic concern, personal distress, and perspective taking; Davis, 1983) queried about trait empathy on a 5-point Likert-type scale (does not describe me well to describes me very well). Sample Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.77 to 0.89.

Racism Against Black Individuals

The 8-item Modern Racism Scale (Henry & Sears, 2002) assessed racial prejudice on 4-point Likert-type scales (one item using a 3-point scale). Higher scores on this measure indicate higher racial prejudice against Black individuals (sample α = 0.72).

State Empathy

Using a 7-point Likert-type scale (not at all to extremely), six adjectives measured state empathic concern (Batson et al., 1987)—sympathetic, moved, compassionate, tender, warm, and softhearted—and seven adjectives assessed empathic distress (Batson et al., 1987)—alarmed, upset, worried, disturbed, perturbed, distressed, troubled. Seven adjectives—angry, irritated, offended, outraged, mad, frustrated, annoyed—measured state empathic anger, a vicarious emotion that occurs when witnessing a person being treated unfairly, and is directed toward the perpetrator(s) (Vitaglione & Barnett, 2003). Two additional adjectives are typically included in this measure of empathic anger—upset and perturbed (Batson et al., 2007)—but were only used to compute empathic distress in this study, as these adjectives are also included in the canonical measure of state empathic distress. Sample alphas on the three scales ranged from 0.85 to 0.94.

Awareness of Ostracism and Races of the Other Players

Four true/false questions regarding the ostracism (e.g., “All players participated in the game the same amount”) were embedded among four filler questions germane to the game (e.g., “One player took much longer to throw the ball than others”) (adapted from Masten et al., 2011). To further conceal the goals of this measure, instructions indicated that, “Because each set of players acts differently, we would like to know how the events of the game unfolded.” Additionally, one item measured awareness of the race of the victim (and those of the other players). Specifically, participants endorsed one statement about the racial identity of the other players (i.e., “All players were a different race than me,” “All players were the same race as me,” “One player was the same race and two were a different race than me,” “One player was a different race and two were the same race as me”).

Instruction and No-Instruction Quality Checks

Six questions were administered after the observed Cyberball game and after the all-play Cyberball game to rule out the possibility that specific aspects of the experimenter-delivered instructions and/or audio recordings explained experimental condition differences in study outcomes. Two questions queried about the participants’ ability to concentrate on the experimenter-delivered instructions: “How easy was it for you to follow the instructions provided by the experimenter?” (7-point Likert-type scale; very difficult to very easy), and “To what extent were you able to focus on the instructions provided by the experimenter? (5-point Likert-type scale; not at all to extremely). Four questions queried participant concentration, comfort, and perceived quality of the audio recording, as follows: “How easy was it for you to follow the recorded audio instructions?” (7-point Likert-type scale; very difficult to very easy); “To what extent were you able to focus on the recorded audio instructions?” and “I felt uncomfortable about the activities the audio recording asked me to do” (both 5-point Likert-type scales; not at all to extremely); and “I felt that the quality of the audio recording was _______” (5-point Likert scale; very poor to very good).

Email Helping

Email responses were submitted to coders naïve to the study hypotheses and masked to training conditions (Masten et al., 2011). For emails addressed to the ostracism victim, four raters coded the extent to which the writer helped the ostracism victim, using a 7-point scale (not at all to very much) in response to three questions: “Does it seem like they are trying to comfort the person?”; “How supportive are they?”; and “How much do they seem like they are trying to help the person?” Item scores were averaged for each rater; these mean scores were then averaged across raters. Interrater consistency was high (ICC = 0.85). In this study and in Study 2, victims received more prosocial emails than perpetrators (p < 0.001), but the race of the perpetrator did not predict email helping (p ≥ 0.833). Thus, ratings of emails to the victim served as our helping outcome. Furthermore, the instruction condition did not predict email helping directed toward perpetrators, nor did it interact with the race of the perpetrator (p ≥ 0.335).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

All participants reported awareness of the ostracism and correctly identified the racial demographics of the other players. Assumptions of analysis of variance and regression were checked prior to analyses, including univariate and multivariate normality (i.e., Mahalanobis Distance), homogeneity of variance (i.e., Levene’s test), normality and linearity of residuals, independence of errors, and outliers (i.e., leverage values and Cook’s distance). Normality and linearity of residuals were checked by visually inspecting the normal probability plot of residuals and the residual scatterplot. Multicollinearity was not assessed as we used orthogonal contrasts. Furthermore, linear relations were not checked because independent variables were categorical. General linear model assumptions were met; however, state empathic concern was leptokurtic with a score of 2.08 (SE = 0.43) so scores were square root–transformed. Given that there were no more than four cases per condition with missing data and that proportion of missing data across all study outcomes was not correlated with the instruction condition (χ2(2) ≤ 2.79, p ≥ 0.248), listwise deletion was used for primary analyses. There were no differences between mindfulness and attention instruction conditions on the instruction quality check questions concerning the main and booster audio-recorded instructions (p ≥ 0.175). Additionally, the instruction quality check questions examining variation in experimenter-delivered instructions did not differ by condition (p ≥ 0.154). Psychological traits were not associated with instruction condition (p ≥ 0.088) so were not further considered. Instruction condition and victim/perpetrator status did not predict the intention to include or exclude the other players (p ≥ 0.779). These preliminary analyses are reported in the Supplementary Material.

Primary Analyses

Table 1 shows one-way ANOVA model results on instruction condition differences in study outcomes. Figure 1 shows distributions of primary study outcomes. A Helmert contrast was created to test the effects of mindfulness and control conditions on study outcomes with the following codes (contrast 1: MI = 0.67, AI = − 0.33, NI = − 0.333; contrast 2: MI = 0, AI = 0.5, NI = − 0.5). Welch ANOVAs were estimated for models with heterogenous group variances. Although mindfulness trainees showed comparatively higher empathic concern after observing ostracism (p = 0.015), the model summary statistics indicated that the two contrasts did not provide a better fit than the mean of empathic concern (p = 0.051). This suggests that the mean differences between mindfulness and control conditions on empathic concern may not be reliable. Mindfulness training, relative to both control conditions (i.e., contrast 1), predicted higher email helping toward ostracized racial outgroup members, explaining 15% of the variance in the outcome. Mindfulness training, however, did not predict inclusion. Mindfulness training was not related to empathic distress or empathic anger (p ≥ 0.320). Table 1 also shows an unexpected difference between the control conditions; no instruction showed higher inclusion than the attention control condition.

Raincloud distributions of Study 1 primary outcomes. Note. Plots created with ggplot2 and ggdist packages for data visualization in the R programming environment (Version 3.6.2; R Core Team, 2021)

Because mindfulness training did not predict inclusion and inclusion was not associated with empathic concern (r(111) = 0.11, p = 0.228), a subsequent test of empathic concern as a mediator of the instruction condition–inclusion relation was not performed. To test whether empathic concern was a reliable mediator of the mindfulness–email helping relation, we used the PROCESS bootstrapping plugin (Model 4, Hayes, 2018) for SPSS. Five thousand resamples with 95% bias-corrected standardized bootstrap confidence intervals were simulated for each model, and the same Helmert contrasts were specified as in previously reported models. As a strong test of Hypothesis 3, which predicted that state empathic concern would mediate the mindfulness and prosocial response relation, empathic distress and empathic anger were loaded into the model as alternative simultaneous mediators. Prior to performing these analyses, assumptions were checked as in ANOVA models, but now included visually inspecting scatterplots for linear relationships between the mediators and outcomes and assessing VIF and tolerance values for multicollinearity. Assumptions of regression were met and so we proceeded with analyses. There was a statistically meaningful total effect of the training condition on email helping (F(2, 119) = 9.33, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.14). Neither state empathic concern (β = 0.04, 95% CI(β) = [− 0.08, 0.19]), empathic distress (β = − 0.00, 95% CI(β) = [− 0.07, 0.07]), nor empathic anger (β = 0.04, 95% CI(β) = [− 0.06, 0.18]) mediated this relation. Mediation paths are reported in the Supplementary Material.

Study 2

Study 1 provided partial support only for our second hypothesis. Berry et al., (2018) found that mindfulness training promoted helping in both private and public contexts, but Study 1 differs from those in that the participants’ photographic image was seen by each ostensible player, rather than being identified by first name only. This may have been an important factor in equalizing public helping. Classic social psychological research shows that people will join in with a group excluding another person (Schachter, 1951), because helping the victim may put the prospective helper at risk of being excluded themselves (Williams, 2009). Of course, this would appear to be true for any type of ostracism context—for example, when one is identified by their first name or by a photographic image. However, photographic images in a computer-mediated communication can increase socially desirable behavior (Burnham, 2003), and because participants were ostensibly seen by the ostracism perpetrators during the all-play game, participants may have been more “tactical” with their throws to avoid negative behaviors from the ostracism perpetrators—ostensibly fellow students at the same university. Consistent with this, participants’ reported intentions to include the victim and the other players did not differ statistically. The use of photographic images may have reduced public prosocial action in the Cyberball environment.

In Study 2, we tested whether the effects of brief mindfulness training on prosocial responsiveness toward ostracized racial outgroup members would occur in a more anonymous context—in this study, when identified by first name only. We reasoned that sharing only first names would allow participants to feel more anonymous in their responses than when a photographic image was shared. As previously mentioned, ostracism is a behavior that is subject to felt pressure to conform to a group that has excluded someone (Williams, 2009). To foster the perception that the first name identified ostracism victim was Black (as well as one of the perpetrators), they were identified using stereotypically Black or African American–sounding names (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004). We retested our three hypotheses from Study 1 with this important variation in the procedure.

Method

Participants

Sample size determination was consistent with that of Study 1 (n = 36 per condition). Participants were over-recruited to account for exclusions based on study suspicion and careless responding. One-hundred thirty-seven self-identifying White undergraduates from a Mid-Atlantic US university received course credit for participation. Five people indicated suspicion about the cover story so were excluded from analyses. No participants were excluded for careless responding. The remaining 132 participants were 74.80% female, with an average age of 19.05 years (SD = 2.40).

Procedures

Experimental procedures largely replicated those presented in Study 1, but two procedural modifications and one measure were added to strengthen the specificity of the claims made about mindfulness training predictions of prosocial responsiveness. First, to increase perceived anonymity, participants were told that only their first names would be loaded into the Cyberball environment. All ostracism victims were gender-matched to the participant and were identified using Black-stereotypical names—Lakisha and Jamal (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004). In addition to identifying race with first names, the racial demographics of each player were indicated on the Cyberball introduction screen prior to beginning the game. The second procedural modification was designed to reduce the possibility of experimental demand and further to conceal the aims of the study; specifically, the awareness of ostracism and the “players” racial demographic manipulation check questions from Study 1 were asked after all study outcomes were assessed.

The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler & Stewart, 2007) was added to the procedure (in modified form) to assess the perceived social status of each of the Cyberball “players.” Race and social status are often correlated (Fiske, 2010), and research suggests that putatively racially driven empathy biases (i.e., pain attributions) appear to be attributable to the perceived social status of victims (e.g., economic hardships) and not to race (Trawalter et al., 2012). The perceived social statuses of the victims and perpetrators of ostracism were assessed after all study outcomes.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

As in Study 1, participants were randomized to either no instruction (NI; n = 35), mindfulness instruction (MI; n = 48), or attention control (AI; n = 49). Like Study 1, regression and ANOVA assumptions were tested but excluded tests of linearity and multicollinearity for ANOVA models. All assumptions were met. All participants indicated noticing the ostracism and correctly identified the racial demographics of the Cyberball players. As in Study 1, listwise deletion was used (see Table 1 for missing data information). There were no meaningful differences in audio-recorded instructions (p ≥ 0.082) or experimenter-delivered instructions (p ≥ 0.069). Mindfulness trainees reported lower trait empathic concern and were more politically liberal than the two controls, so these two variables were statistically controlled in primary analyses. As predicted, participants indicated a higher intention to include victims versus perpetrators. Participants also perceived the social status of the Black victim to be lower than that of the two perpetrators. Preliminary analyses are reported in the Supplementary Material.

Primary Analyses

Table 1 shows one-way ANOVA model results on instruction condition differences in study outcomes. Figure 2 depicts raincloud distributions of primary outcomes. As in Study 1, a Helmert contrast was created to test the effects of mindfulness and control conditions on study outcomes. Welch ANOVAs were estimated for models with heterogenous group variances. Consistent with previous research (Berry et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2014), brief mindfulness training, relative to the two control conditions, predicted higher state empathic concern, email helping, and inclusion, explaining between 7 and 8% of the variance in these outcomes. Mindfulness trainees also perceived the White perpetrator’s social status as lower than did those in the two control conditions. Mindfulness instruction was not related to empathic distress, empathic anger, intention to include any of the players, and perceived social status of the Black perpetrator and victim. The attention control trainees showed lower empathic distress and empathic anger than did the no-instruction controls but did not differ on any additional study outcomes.

Raincloud distributions of Study 2 primary outcomes. Note. Plots created with ggplot2 and ggdist packages for data visualization in the R programming environment (Version 3.6.2; R Core Team, 2021)

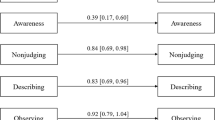

Two mediation models were constructed as in Study 1, and assumptions of regression were met (including linearity and multicollinearity). There was a statistically meaningful total effect of training condition on email helping (F(2, 121) = 4.57, p = 0.012, R2 = 0.07). Figure 3 shows that neither state empathic concern (β = 0.10, 95% CI(β) = [− 0.01, 0.24]), empathic distress (β = − 0.02, 95% CI(β) = [− 0.12, 0.07]), nor empathic anger (β = 0.01, 95% CI(β) = [− 0.07, 0.12]) mediated this relation. It is noteworthy that the a- and b-paths for empathic concern were statistically significant in this model. There was a significant total effect of the mindfulness–inclusion relation F(2, 121) = 5.10, p = 0.008, R2 = 0.08), and consistent with our third hypothesis, state empathic concern explained a significant portion of the variance in this causal relation (β = 0.17, 95% CI(β) = [0.02, 0.39]). Empathic distress (β = − 0.04, CI(β) = [− 0.20, 0.03]) and empathic anger (β = 0.03, CI(β) = [− 0.04, 0.15]) did not mediate the mindfulness–inclusion relation. Controlling for trait empathic concern and political affiliation did not meaningfully change the relations reported herein. All contrast 2 mediation paths were non-significant (see Supplementary Material).

Study 2 mindfulness training–helping behavior relations. Note. Standardized path coefficients are shown, and the direct effect of mindfulness on helping is parenthesized. Solid line pathways indicate significant meditation; dashed line pathways indicate non-significant mediation of the instruction condition–helping behavior relations

General Discussion

With increased access to digitally mediated communication and increased economic and political interdependence, humans are in greater contact with people of other races and are often exposed to their suffering in online and in-person interactions. Yet, decades of research indicate that humans show less empathy and helping behavior toward racial (and other) outgroup members in need (e.g., Cikara et al., 2011; Saucier, 2015). Therefore, means to increase interracial prosociality are of profound significance in today’s world. To our knowledge, these two studies are the first to test whether brief mindfulness training would increase empathic concern for and helping behavior toward ostracized racial outgroup members. We anticipated that mindfulness would promote helping behavior and do so via increases in empathic concern. Support for our study hypotheses was obtained, but primarily when participants’ and other ostensible participants’ identities were comparatively anonymous. Specifically, in Study 1, wherein photographs of participants and other players in the Cyberball game were used, briefly instructed mindfulness, relative to attentional control instructions and no instruction, predicted higher email helping toward an ostracized racial outgroup member but not game inclusion or empathic concern. Study 2 extended these findings by showing that briefly instructed mindfulness also increased empathic concern and inclusion of an ostracized racial outgroup member under conditions of greater perceived anonymity—that is when presenting only participants’ and other players’ first names. Additionally, empathic concern explained a significant proportion of the variance in the causal relation between mindfulness and public helping behavior in Study 2, and importantly these effects were not due to empathic anger or empathic distress.

These findings, particularly those of Study 2, are consistent with previous research by Berry et al., (2018) that showed briefly trained mindfulness increased helping behavior toward a victim of ostracism through an other-oriented prosocial emotion—empathic concern. Consistent with this, mindfulness was not related to empathic distress or empathic anger, two self-oriented emotions. These findings also support mindfulness theory (Berry & Brown, 2017; Berry et al., 2022; Davidson & Harrington, 2002), and empirical work (e.g., Lueke & Gibson, 2016) indicating that mindfulness promotes prosocial action. Most importantly, brief mindfulness instructions promoted empathic concern and prosocial action toward a racial outgroup member in contexts with relatively higher anonymity. Thus, this finding extends previous research by showing that when instructed to be mindful, prosociality is not reserved for social ingroup members. Study 2 supported Hypotheses 1 and 2, and partially supported Hypothesis 3. Empathic concern in both studies did not mediate the relation between mindfulness and (private) email helping. Both the a- and b-paths of this mediation model were statistically meaningful in Study 2 (but not Study 1) and in the direction we predicted; however, the relation between empathic concern and email helping was modest (β = 0.22).

While this research supports theory and prior science, it uncovers new boundary conditions of the mindfulness effects on prosocial responsiveness. In particular, the studies suggest that relative anonymity may be important for highlighting the value of mindfulness for prosocial behavior. The participants were told in both studies that the ostensible players were fellow students from the introductory psychology participant pool, so the conditions of Study 1, in which the participants’ photographic image was posted in the Cyberball game, potentially raised the participants’ concern that they would become victims of punitive social behavior from the other ostensible participants if they helped. Ostracism is a potent social act used to correct a group member’s behavior (Brewer & Caporael, 2006; Nezlek et al., 2015), and helping an ostracized person can carry significant consequences for the prospective helper (Williams, 2009). Thus, being easily identifiable, participants across conditions in Study 1 might have been more tactical with their public behavior (ball throws), including all players equally. These studies suggest that mindfulness instruction increases helping behavior toward an ostracized person when the risk of others’ ostracism is mitigated through perceived anonymity, as in Study 2. Future work could further test this argument by having players exclude a clear social deviate (i.e., one who burdens the other players by taking a long time to throw the ball; Wesselmann et al., 2015), and by assessing participants’ concerns about the consequences of their ball-tossing strategy. Such research could also broaden theory on mindfulness and ostracism by examining mindfulness effects on prosociality in contexts in which it is socially disadvantageous to help or comfort an ostracism victim.

The fact that mindfulness instruction increased prosocial emotion and behavior under conditions of relative anonymity is interesting because classic research suggests that humans are more likely to engage in immoral and impulsive acts when their identity is unknown (e.g., Diener et al., 1976), and more recent research suggests that humans withhold prosociality in contexts of perceived anonymity (Dana et al., 2007; Nettle et al., 2013). Additionally, people are more likely to join a group that is ostracizing someone rather than stop the ostracism (Schachter, 1951) for fear that if they do not conform, they too will be ostracized (Williams, 2009). The present results suggest that, in a relatively anonymous context, a mindful state may help to mitigate such concerns. To test these hypotheses directly, researchers should experimentally manipulate anonymity and measure participants’ concerns about being ostracized themselves.

It is important to ask whether participants in the control conditions showed lower than normative levels of prosociality rather than concluding that mindfulness increased it. There are two reasons to suggest that this was not the case. First, the attention controls across both studies did not show less prosocial behavior than those receiving no instruction, the latter condition meant to reflect normative (non-manipulated) behavior. Second, while it is possible that control participants in Study 2 engaged in lower than normative inclusion behavior, spurred by greater perceived anonymity, control participants in Study 1 and Study 2 did not differ in their intention to include the victim nor in their inclusion behavior (p ≥ 0.120).

Limitations and Future Directions

The present investigation is limited to Internet-based contexts in which the ostracized racial outgroup members’ emotional states are not seen directly. It is also not possible to generalize these results to real-world prosocial action in which one’s identity is often known by the help recipient. But recent research has found that training in mindfulness promotes self-reported interracial helping in daily life (Berry et al., 2021).

There are four study design limitations of note. First, it would have been more appropriate to measure psychological traits outside of the study context to reduce experimenter demand. However, we placed all trait questionnaires pertaining to empathy and helping after the study outcomes were assessed to circumvent influence on the study outcomes. Second, the placement of manipulation checks and state emotion measures could have made participants aware of the study aims. Yet, in Study 2, manipulation checks were taken after all study outcomes were completed to reduce this potential bias. While it is still possible that participants became aware of the study aims when completing the state emotion measures, there is no reason to believe that mindfulness participants would have been differentially more aware that these items were related to the outcomes that followed. Moreover, post-experimental inquiries assessed participants’ study suspicion, and participants were told that they received full compensation prior to completing the post-experimental inquiry to mitigate any misreporting of study suspicion for fear of not receiving the participation incentive (Orne, 2009). Third, the randomization failed to equally distribute Study 2 participants on their political affiliation and trait empathic concern scores. These covariates were statistically controlled but could contribute to the efficacy of the instructions in producing prosociality. Fourth, an empathy target was not specified in our state empathy measures. We chose this approach to increase the experimental realism of our cover story and reduce experimenter demand. This approach makes it difficult to specify toward whom empathy was being directed.

Two additional study limitations pertain to ambiguity about the intergroup context under study. First, most individuals belong to a range of social categories simultaneously (e.g., socioeconomic status, sex, race). Thus, empathic concern and helping responses in the Cyberball environment could also be predicted by whatever social category was most salient to the participant (Mitchell et al., 2003). However, the fact that all participants noted that the victim was a different race than them and that they rated the victim as of a lower social status than the other players lends support to the idea that participants were helping a member of a disadvantaged group. Future research could study the effects of mindfulness on interracial prosociality when the group status of the victim is manipulated (e.g., Yzerbyt et al., 2003). Second, group-level emotions differ from individual-level emotions in their antecedents and consequences (e.g., Smith & Mackie, 2016). Empathic concern has been characterized as an inherently individual-level emotion, and group-level emotions such as collective guilt and especially moral outrage are more effective at promoting equitable treatment and reparative behaviors between groups (see Thomas et al., 2009 for review). To understand how best to apply mindfulness training to galvanize social justice, future work will need to examine helping behaviors and emotions that more directly measure equitable sharing of limited resources and in contexts where the victim’s need is ambiguous. Future work should also investigate group-level emotions and behaviors instead of individual-level responses, as done in this research. Moreover, future research ought to examine the effects of longer-term mindfulness training on sustaining interracial prosocial actions over time, and perhaps complementing current efforts to improve interracial interactions (e.g., Klimecki, 2019).

Why mindfulness conduces to other-oriented emotion and helping in interracial contexts remains an open question. Here we discuss three possible mechanisms of the effect of mindfulness on interracial prosociality. First, as a receptive attention to what one is presently experiencing, mindfulness may reduce automatic activation of implicit biases and automatic affective responses to racial outgroup members (Berry & Brown, 2017; Berry et al., 2022; Kang et al., 2014). Incipient research has shown that brief training in mindfulness reduces automatic activation of implicit race bias (Lueke & Gibson, 2015). Second, deficits in interracial prosociality may neither be evident to nor endorsed by White individuals (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2000). Instead, when White individuals withhold help from Black and other racial outgroup members, they often attribute it to non-racial characteristics of the social context (e.g., help is too effortful, time-consuming, risky, and/or inconvenient; Saucier, 2015). Indeed, deficits in interracial prosociality may persist because people lack explicit awareness of their racial biases (e.g., Devine, 1989). Knowledge-focused intervention research suggests that first making individuals aware of their biases may facilitate bias reduction over time among individuals who are motivated to reduce their biases (Cooley et al., 2018; Devine et al., 2012). To our knowledge, studies have yet to find that mindfulness increases awareness of one’s biases or the motivation to reduce them in interracial contexts. Future research could explore the role of reduced implicit bias as a mechanism of mindfulness-induced increases in interracial prosociality by measuring it (e.g., with an Implicit Association Test; Greenwald et al., 1998) prior to assessing interracial prosocial behavior. However, the intervention used herein is unlikely to engender lasting states of mindfulness, and longer-term mindfulness training may be necessary to examine this effect. Perhaps identifying discrepancies between how one should and would act in interracial interactions (e.g., Monteith et al., 2001) could also serve as a tractable means for measuring awareness of bias cues (Devine et al., 2012).

A third possible mechanism of the mindfulness—interracial prosociality relation is that mindfulness attenuates the perceived psychological boundaries between oneself and others (DeSteno, 2015). Here we only found partial support related to this for Hypothesis 3; previous research indicates that empathy is a more reliable promoter of ingroup prosociality as opposed to outgroup prosociality (Stürmer et al., 2006), and thus perceived oneness with racial (or any) outgroup members may not be less strongly related to helping them. Future work could test this claim in multiple ways. For instance, mindfulness trainees could report on the extent to which they include the self-concept of an outgroup member in apparent need into their own self-concept (Aron et al., 1992), a known proximal promoter of helping behavior (Cialdini et al., 1997). Related to this, the “gap” in empathy in which preference is given to ingroup over outgroup members is associated with conflict, and nascent evidence suggests that mindfulness practices may close this gap (Behler & Berry, 2022).

Finally, the studies herein cannot yet fully speak to the benefits of mindfulness for reducing racism and intergroup conflict. As a first test of the effects of mindfulness practice on interracial prosociality, we held race constant by recruiting only White participants who observed a Black ostensible empathy target. While this is a common methodological approach in intergroup research (Roberts et al., 2020), we encourage researchers to expand on the breadth of these findings to inform intergroup prosociality theory and its application. Empathizers and empathy recipients have different social goals, and in interracial contexts are often marked by power asymmetries in which dominant and non-dominant groups also have diverging goals (Bergsieker et al., 2010). Future research should consider not only how members of dominant groups respond to mindfulness training in intergroup contexts, but also the benefits for members of non-dominant social groups (e.g., Batson, 2017). For example, dominant group members may feel empathy paternalistically (Schneider et al., 1996) or to appear unprejudiced (Richeson & Shelton, 2003), while non-dominant group members may not trust dominant group members’ intentions (Kunstman et al., 2016) or fear rejection by dominant group members (Shelton & Richeson, 2005). Berry et al., (2022) have provided some direction for testing the broader range of theories on racism and intergroup prosociality within contemplative science. Specifically, they suggest that including contemplative practices into intergroup dyadic interactions could inform about the mutual benefits (or lack thereof) of contemplative practices for members from different social groups.

This research extends previous work on the positive interpersonal outcomes of mindfulness training (Berry et al., 2018), by showing that brief training in mindfulness can promote interracial prosocial responsiveness. Racism remains an abiding concern in many societies, and racial and other outgroup members are less often the recipients of others’ kindness. While this work shows promise, future work should examine how best to implement mindfulness training to promote lasting increases in interracial prosociality.

Data Availability

Data are publicly available on the Open Science Framework at the following link (https://osf.io/62jdp/).

References

Adler, N., & Stewart, J. (2007). The MacArthur scale of subjective social status. MacArthur Research Network on SES & Health. http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/Research/Psychosocial/subjective.

Anālayo, B. (2020). Attention and mindfulness. Mindfulness, 11(5), 1131–1138.

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612.

Ashar, Y. K., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Dimidjian, S., & Wager, T. D. (2017). Empathic care and distress: Predictive brain markers and dissociable brain systems. Neuron, 94(6), 1263–1273.

Batson, C. D. (2009). These things called empathy: Eight related but distinct phenomena. In J. Decety & W. Ickes (Eds.), The social neuroscience of empathy (pp. 3–15). American Psychological Association.

Batson, C. D., & Ahmad, N. Y. (2009). Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 3, 141–177.

Batson, C. D., Fultz, J., & Schoenrade, P. A. (1987). Distress and empathy: Two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality, 55(1), 19–39.

Batson, C. D., Polycarpou, M. P., Harmon-Jones, E., Imhoff, H. J., Mitchener, E. C., Bednar, L. L., Klein, T. R., & Highberger, L. (1997). Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 105–118.

Batson, C. D. (2017). The empathy-altruism hypothesis: What and so what. In E. M., Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 27–40). Oxford University Press.

Beeney, J. E., Franklin, R. G., Jr., Levy, K. N., & Adams, R. B., Jr. (2011). I feel your pain: Emotional closeness modulates neural responses to empathically experienced rejection. Social Neuroscience, 6(4), 369–376.

Behler, A. M. C., & Berry, D. R. (2022). Closing the empathy gap: A narrative review of the measurement and reduction of parochial empathy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16(9), e12701.

Bergsieker, H. B., Shelton, J. N., & Richeson, J. A. (2010). To be liked versus respected: Divergent goals in interracial interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(2), 248–264.

Berry, D. R., & Brown, K. W. (2017). Reducing separateness with presence: How mindfulness catalyzes intergroup prosociality. In J. Karremans & E. Papies (Eds.), Mindfulness in social psychology (pp. 153–166). Psychology Press.

Berry, D. R., Cairo, A. H., Goodman, R. J., Quaglia, J. T., Green, J. D., & Brown, K. W. (2018). Mindfulness increases prosocial responses toward ostracized strangers through empathic concern. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(1), 93–112.

Berry, D. R., Hoerr, J. P., Cesko, S., Alayoubi, A., Carpio, K., Zirzow, H., Walters, W., Scram, G., Rodriguez, K., & Beaver, V. (2020). Does mindfulness training without explicit ethics-based instruction promote prosocial behaviors? A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(8), 1247–1269.

Berry, D. R., Wall, C. S., Tubbs, J. D., Zeidan, F., & Brown, K. W. (2021). Short-term training in mindfulness predicts helping behavior toward racial ingroup and outgroup members. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(1), 60–71.

Berry, D. R., Rodriguez, K., Tasulis, G., & Behler, A. M. C. (2022). Mindful attention as a skillful means toward intergroup prosociality. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01926-3

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013.

Brewer, M. B., & Caporael, L. R. (2006). An evolutionary perspective on social identity: Revisiting groups. In M. Schaller, J. A. Simpson, & D. T. Kenrick (Eds.), Evolution and Social Psychology (pp. 143–161). Psychology Press.

Brewer, J. A., Worhunsky, P. D., Gray, J. R., Tang, Y. Y., Weber, J., & Kober, H. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(50), 20254–20259.

Brown, K. W., & Cordon, S. (2009). Toward a phenomenology of mindfulness: Subjective experience and emotional correlates. In F. Didonna (Ed.), Clinical handbook of mindfulness (pp. 59–81). Springer.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Brown, K. W., Goodman, R. J., Ryan, R. M., & Anālayo, B. (2016). Mindfulness enhances episodic memory performance: Evidence from a multimethod investigation. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0153309.

Burnham, T. C. (2003). Engineering altruism: A theoretical and experimental investigation of anonymity and gift giving. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 50(1), 133–144.

Chin, B., Lindsay, E. K., Greco, C. M., Brown, K. W., Smyth, J. M., Wright, A. G., & Creswell, J. D. (2021). Mindfulness interventions improve momentary and trait measures of attentional control: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 150(4), 686–699.

Christoff, K., Gordon, A. M., Smallwood, J., Smith, R., & Schooler, J. W. (2009). Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(21), 8719–8724.

Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S. L., Lewis, B. P., Luce, C., & Neuberg, S. L. (1997). Reinterpreting the empathy–altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(3), 481–494.

Cikara, M., Bruneau, E. G., & Saxe, R. R. (2011). Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 149–153.

Cooley, E., Lei, R. F., & Ellerkamp, T. (2018). The mixed outcomes of taking ownership for implicit racial biases. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(10), 1424–1434.

Covey, S. R., Merrill, A. R., & Merrill, R. R. (1995). First things first. Simon and Schuster.

Dana, J., Weber, R. A., & Kuang, J. X. (2007). Exploiting moral wiggle room: Experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Economic Theory, 33(1), 67–80.

Davidson, R. J., & Harrington, A. (2002). Visions of compassion: Western scientists and Tibetan Buddhists examine human nature. Oxford University Press.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 167–184.

DeSteno, D. (2015). Compassion and altruism: How our minds determine who is worthy of help. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 80–83.

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18.

Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267–1278.

Dickert, S., & Slovic, P. (2009). Attentional mechanisms in the generation of sympathy. Judgment and Decision Making, 4(4), 297–306.

Diener, E., Fraser, S. C., Beaman, A. L., & Kelem, R. T. (1976). Effects of deindividuation variables on stealing among Halloween trick-or-treaters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33(2), 178–183.

Donald, J. N., Sahdra, B. K., Van Zanden, B., Duineveld, J. J., Atkins, P. W., Marshall, S. L., & Ciarrochi, J. (2019). Does your mindfulness benefit others? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the link between mindfulness and prosocial behaviour. British Journal of Psychology, 110(1), 101–125.

Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2000). Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychological Science, 11(4), 315–319.

Dovidio, J. F., Johnson, J. D., Gaertner, S. L., Pearson, A. R., Saguy, T., & Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2010). Empathy and intergroup relations. In M. E. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 393–408). American Psychological Association.

Enock, F. E., Tipper, S. P., & Over, H. (2021). Intergroup preference, not dehumanization, explains social biases in emotion attribution. Cognition, 216, 104865.

Farb, N. A., Segal, Z. V., Mayberg, H., Bean, J., McKeon, D., Fatima, Z., & Anderson, A. K. (2007). Attending to the present: Mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2(4), 313–322.

Fennis, B. M. (2011). Can’t get over me: Ego depletion attenuates prosocial effects of perspective taking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(5), 580–585.

Fiske, S. T. (2010). Interpersonal stratification: Status, power, and subordination. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 941–982). Wiley.

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., & Johnson, G. (1982). Race of victim, nonresponsive bystanders, and helping behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 117(1), 69–77.

Galinsky, A. D., Ku, G., & Wang, C. S. (2005). Perspective-taking and self-other overlap: Fostering social bonds and facilitating social coordination. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 8(2), 109–124.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480.

Gutsell, J. N., & Inzlicht, M. (2012). Intergroup differences in the sharing of emotive states: Neural evidence of an empathy gap. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(5), 596–603.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The symbolic racism 2000 scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253–283.

Howarth, A., Smith, J. G., Perkins-Porras, L., & Ussher, M. (2019). Effects of brief mindfulness-based interventions on health-related outcomes: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 10(10), 1957–1968.

Kang, Y., Gruber, J., & Gray, J. R. (2014). Mindfulness: Deautomatization of cognitive and emotional life. In A. Ie, C. T. Ngnoumen, & E. J. Langer (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of mindfulness (pp. 168–185). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Karremans, J. C., & Papies, E. K. (2017). Mindfulness in social psychology. Routledge.

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932–932.

Klimecki, O. M. (2019). The role of empathy and compassion in conflict resolution. Emotion Review, 11(4), 310–325.

Kreplin, U., Farias, M., & Brazil, I. A. (2018). The limited prosocial effects of meditation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 2403.

Kunstman, J. W., & Plant, E. A. (2008). Racing to help: Racial bias in high emergency helping situations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1499–1510.

Kunstman, J. W., Tuscherer, T., Trawalter, S., & Lloyd, E. P. (2016). What lies beneath? Minority group members’ suspicion of Whites’ egalitarian motivation predicts responses to Whites’ smiles. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(9), 1193–1205.

Kurzban, R., Burton-Chellew, M. N., & West, S. A. (2015). The evolution of altruism in humans. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 575–599.

Leyens, J. P., Paladino, P. M., Rodriguez-Torres, R., Vaes, J., Demoulin, S., Rodriguez-Perez, A., & Gaunt, R. (2000). The emotional side of prejudice: The attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 186–197.

Lueke, A., & Gibson, B. (2015). Mindfulness meditation reduces implicit age and race bias: The role of reduced automaticity of responding. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(3), 284–291.

Lueke, A., & Gibson, B. (2016). Brief mindfulness meditation reduces discrimination. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3(1), 34–44.

Lutz, A., Jha, A. P., Dunne, J. D., & Saron, C. D. (2015). Investigating the phenomenological matrix of mindfulness-related practices from a neurocognitive perspective. American Psychologist, 70, 632–658.

Masten, C. L., Morelli, S. A., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2011). An fMRI investigation of empathy for “social pain” and subsequent prosocial behavior. NeuroImage, 55(1), 381–388.

Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 437–455.

Meyer, M. L., Masten, C. L., Ma, Y., Wang, C., Shi, Z., Eisenberger, N. I., & Han, S. (2013). Empathy for the social suffering of friends and strangers recruits distinct patterns of brain activation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(4), 446–454.

Minear, M., & Park, D. C. (2004). A lifespan database of adult facial stimuli. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 630–633.

Mitchell, J. P., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Contextual variations in implicit evaluation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 132(3), 455.

Monteith, M. J., Voils, C. I., & Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2001). Taking a look underground: Detecting, interpreting, and reacting to implicit racial biases. Social Cognition, 19(4), 395–417.

Nadler, A. (2002). Inter–group helping relations as power relations: Maintaining or challenging social dominance between groups through helping. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 487–502.

Nettle, D., Harper, Z., Kidson, A., Stone, R., Penton-Voak, I. S., & Bateson, M. (2013). The watching eyes effect in the Dictator Game: It’s not how much you give, it’s being seen to give something. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34(1), 35–40.

Nezlek, J. B., Wesselmann, E. D., Wheeler, L., & Williams, K. D. (2015). Ostracism in everyday life: The effects of ostracism on those who ostracize. The Journal of Social Psychology, 155(5), 432–451.

Orne, M. T. (2009). Demand characteristics and the concept of quasi-controls. In R. Rosenthal & R. L. Rosnow (Eds.), Artifacts in Behavioral Research: Robert Rosenthal and Ralph L. Rosnow’s classic books (pp. 110–137). Oxford University Press.

Park, B., & Judd, C. M. (1990). Measures and models of perceived group variability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(2), 173–191.

Quaglia, J. T., Brown, K. W., Lindsay, E. K., Creswell, J. D., & Goodman, R. J. (2015). From conceptualization to operationalization of mindfulness. In K. W. Brown, J. D. Creswell, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 151–170). Guilford Press.

Quaglia, J. T., Braun, S. E., Freeman, S. P., McDaniel, M. A., & Brown, K. W. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for effects of mindfulness training on dimensions of self-reported dispositional mindfulness. Psychological Assessment, 28(7), 803–818.

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2003). When prejudice does not pay: Effects of interracial contact on executive function. Psychological Science, 14(3), 287–290.

Riem, M. M. E., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Huffmeijer, R., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2013). Does intranasal oxytocin promote prosocial behavior to an excluded fellow player? A randomized-controlled trial with Cyberball. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 8, 1418–1425.

Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: Trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1295–1309.

Rothbart, M., & Taylor, M. (1992). Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds? In G. R. Semin & K. Fiedler (Eds.), Language and social cognition (pp. 11–36). Sage.

Sargent, M. (2004). Less thought, more punishment: Need for cognition predicts support for punitive responses to crime. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1485–1493.

Saucier, D. A. (2015). Race and prosocial behavior. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 392–414). Oxford University Press.

Schachter, S. (1951). Deviation, rejection, and communication. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 46(2), 190–207.

Schindler, S., & Friese, M. (2022). The relation of mindfulness and prosocial behavior: What do we (not) know? Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 151–156.

Schneider, M. E., Major, B., Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1996). Social stigma and the potential costs of assumptive help. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(2), 201–209.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. Guilford Press.

Shelton, J. N., & Richeson, J. A. (2005). Intergroup contact and pluralistic ignorance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(1), 91–17.

Smith, E. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2016). Intergroup emotions. In L. F. Barrett, M. Lewis, & J. M. Hivalind-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 412–421). Guilford Press.

Stürmer, S., Snyder, M., Kropp, A., & Siem, B. (2006). Empathy-motivated helping: The moderating role of group membership. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(7), 943–956.

Tan, L. B., Lo, B. C., & Macrae, C. N. (2014). Brief mindfulness meditation improves mental state attribution and empathizing. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e110510.

Taylor, V. A., Daneault, V., Grant, J., Scavone, G., Breton, E., Roffe-Vidal, S., & Beauregard, M. (2013). Impact of meditation training on the default mode network during a restful state. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), 4–14.

Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C., & Mavor, K. I. (2009). Transforming “apathy into movement”: The role of prosocial emotions in motivating action for social change. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13(4), 310–333.

Tomasello, M. (2009). Why we cooperate. MIT Press.

Trawalter, S., Hoffman, K. M., & Waytz, A. (2012). Racial bias in perceptions of others’ pain. PLoS ONE, 7(11), e48546.

Vescio, T. K., Sechrist, G. B., & Paolucci, M. P. (2003). Perspective taking and prejudice reduction: The mediational role of empathy arousal and situational attributions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(4), 455–472.

Vescio, T. K., Gervais, S. J., Snyder, M., & Hoover, A. (2005). Power and the creation of patronizing environments: The stereotype-based behaviors of the powerful and their effects on female performance in masculine domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(4), 658–672.

Vitaglione, G. D., & Barnett, M. A. (2003). Assessing a new dimension of empathy: Empathic anger as a predictor of helping and punishing desires. Motivation and Emotion, 27(4), 301–325.

Wesselmann, E. D., Wirth, J. H., Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Williams, K. D. (2015). The role of burden and deviation in ostracizing others. The Journal of Social Psychology, 155(5), 483–496.

Williams, K. D. (2009). Ostracism: A temporal need-threat model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 275–314.

Williams, K. S., Yeager, D.S., Cheung, C.K.T., & Choi, W. (2012). Cyberball (version 4.0) [Software]. https://cyberball.wikispaces.com.

Yzerbyt, V., Dumont, M., Wigboldus, D., & Gordijn, E. (2003). I feel for us: The impact of categorization and identification on emotions and action tendencies. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(4), 533–549.

Zaki, J., & Cikara, M. (2015). Addressing empathic failures. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(6), 471–476.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Daniel Berry: study design, protocol design, data analysis, wrote first draft of manuscript. Catherine S. J. Wall: data curation, data visualization, protocol design, editing, writing reviewing. Athena H. Cairo: study design, protocol design, editing, writing reviewing. Paul E. Plonski: protocol design, editing, writing. Larry D. Boman: data analysis, editing. Katie Rodriguez: data analysis, editing. Kirk Warren Brown: study design, co-wrote first draft of manuscript, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The two study protocols herein were approved by the Institutional Review Board (#HM20002328) at Virginia Commonwealth University on October 6, 2014.

Informed Consent

All participants gave informed consent prior to enrolling in the studies herein.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berry, D.R., Wall, C.S.J., Cairo, A.H. et al. Brief Mindfulness Instruction Predicts Anonymous Prosocial Helping of an Ostracized Racial Outgroup Member. Mindfulness 14, 378–394 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-02058-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-02058-4