Abstract

Objectives

Compassion for others is linked to positive outcomes ranging from stress reduction to prosocial behaviour. However, the personality traits that contribute to compassion have not been well established. We sought to explore the individual differences most strongly related to dispositional compassion in Canada and Spain using the HEXACO model of personality.

Methods

Canadian (N = 555; 75.8% women) and Spanish (N = 371; 60.8% women) adults aged 17 to 68 years completed the HEXACO-60 personality inventory, a trait emotional intelligence (EI) scale, and a measure of compassion for others using online survey software. The factor structure and cultural invariance of the compassion measure were assessed, and regression analyses were calculated to determine the strongest predictors of compassion.

Results

In both samples, emotionality was the strongest predictor of compassion, accounting for about 10% of the unique variance in scores. Trait EI, honesty-humility, and openness also predicted compassion, while agreeableness was significant only among Canadians, suggesting there is at least one cross-cultural difference in personality antecedents.

Conclusions

Emotionality and emotional intelligence were strongly linked to compassionate individuals in two distinct cultures, and honesty-humility and openness were weakly predictive as well. Agreeableness was only related among Canadians, suggesting that while the degree to which agreeableness predicts compassion is dependent on the cultural context, the personality antecedents of compassion are similar across cultures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the past two decades, compassion has emerged as a focus of scientific inquiry (Kirby et al. 2017; Oman 2011). While most compassion research is situated in medicine (e.g., Duarte et al. 2016; Sinclair et al. 2017), social work (e.g., Brill and Nahmani 2017; Collins and Garlington 2017), and clinical psychology (e.g., Steindl et al. 2018) domains, what is known so far about compassion in daily life is also promising. Dispositional compassion increases resilience to trauma (Fredrickson et al. 2003) and stress (Pace et al. 2008), and encourages prosocial behaviour (Leiberg et al. 2011). Furthermore, compassion ‘interventions’ can increase positive emotions (Fredrickson et al. 2008; Klimecki et al. 2012; Mongrain et al. 2011), enhance self-esteem (Mongrain et al. 2011), and promote social connectedness (Hutcherson et al. 2008).

In philosophical and spiritual scholarship, there has been interest in compassion for thousands of years. Compassion features prominently in Buddhism, where it is considered the highest virtue (Dalai Lama 1995; Kirby et al. 2017). The lack of compassion research in psychology has resulted partly from definitional difficulties, as it is often used interchangeably with strengths like kindness, empathy, sympathy, and altruism by both laypeople and academics. However, researchers are beginning to converge on a multidimensional definition that is characterized by the ability to recognize emotional distress coupled with a motivation to help (Neff 2003; Pommier 2011). Different models have been suggested, but almost all include the capability to recognize emotions, possessing concern for others who are suffering, and having a desire to alleviate suffering (Dalai Lama 1995; Gilbert 2014; Gu et al. 2017; Kirby et al. 2017; Neff 2003; Pommier 2011; Strauss et al. 2016).

Empathy is defined as the ability to understand the emotions of others and experience a congruent affect, and it is the construct most frequently conflated with compassion. What distinguishes compassion from empathy (and from sympathy and pity) is its motivational caring component (Goetz et al. 2010). Previous research has found that compassion not only correlates with empathy (Klimecki et al. 2012; Sprecher and Fehr 2005) but also provides explanatory power beyond it (e.g. it is compassion that promotes prosocial behaviour, owing to its motivational quality; Lim et al. 2015; Lim and DeSteno 2016). A grounded theory study of palliative care patients suggested that most people can distinguish compassion from empathy, perceiving compassion as more altruistic and loving (Sinclair et al. 2017).

An unresolved question is what predisposes someone to experiencing compassion, or in other words, what comprises the profile of a compassionate person. A second question is how compassion might differ across cultures. Steindl et al. (2019) observed that social roles can influence the expression of compassion, finding differences between Australians and Singaporeans on both compassionate actions and the fear of receiving compassion. However, to our knowledge, little other research has been conducted on the topic.

There are several personality traits that should, theoretically, predict compassion. Here, we opted to employ the HEXACO model of personality rather than the widely used five-factor model (FFM; McCrae and Costa 1987). While several HEXACO domains resemble the FFM, HEXACO has numerous advantages (for a detailed review, see Ashton and Lee 2007). Most pertinent is that its six factors—honesty-humility, emotionality, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness—have emerged organically in lexical studies across at least 12 diverse cultures (Ashton and Lee 2001; Ashton et al. 2004; Ashton and Lee 2007). This is an important benefit, as some psychologists have questioned whether personality inventories are applicable across different cultural contexts (e.g. Poortinga and Van Hemert 2001). Additionally, HEXACO is demonstrably superior in explaining prosocial characteristics like altruism (Ashton and Lee 2007), making it more relevant to compassion research. Much of the literature on human strengths in social and personality psychology has used the FFM; fortunately, however, HEXACO and the FFM have demonstrated strong convergence between analogous domains (Ashton et al. 2008; Gaughan et al. 2012) suggesting that the FFM can inform predictions about HEXACO.

First, honesty-humility is characterized by sincerity, lack of manipulative tendencies, and modesty, versus egocentrism and selfishness (Ashton et al. 2004; Lee and Ashton 2004). Honesty-humility represents a good-natured, considerate outlook that should be a prerequisite for compassion. Common humanity—a non-judgmental recognition of the human condition—is a component of Pommier’s (2011) and Neff’s (2003) compassion construct, and this interconnectedness seems unlikely to manifest with low honesty-humility.

Second, emotionality is characterized by sensitivity, perceived interconnectedness, and sentimentality (Lee and Ashton 2004). It is one of the domains that, across cultures, best captures altruism (along with honesty-humility and agreeableness; Ashton and Lee 2007). However, it should be noted that mindfulness (the tendency to engage with others without becoming overwhelmed) is an aspect of Pommier’s (2011) Compassion Scale, and that emotionality contains some content (specifically fearfulness and anxiety) that could relate negatively with mindfulness.

Third, like emotionality, extraversion has an affective component and relates to prosocial variables. The literature on empathy can partly inform predictions about compassion, and extraversion has demonstrated positive relationships with scores on Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright’s (2004) Empathy Quotient (EQ) in Japan (Wakabayashi and Kawashima 2015) and the USA (Nettle 2007).

Fourth, agreeableness has shown to relate to empathy in American, Spanish, Chinese, German, and Japanese samples (Del Barrio et al. 2004; Melchers et al. 2016; Nettle 2007; Wakabayashi and Kawashima 2015). Agreeableness also predicts prosocial behaviour (Graziano and Eisenberg 1997) and forgivingness (Shepherd and Belicki 2008). Additionally, because many extraversion and agreeableness HEXACO items refer to adaptive interpersonal functioning (Lee and Ashton 2004), it is likely that compassion would correlate with both. In short, there are possible links between honesty-humility, emotionality, agreeableness, and extraversion with compassion, owing both to the theoretical content of these domains and to previous research involving other prosocial variables.

There are individual differences that cannot be subsumed under HEXACO, an important one being trait emotional intelligence (EI; Petrides and Furnham 2001). Trait EI is a collection of perceptions about one’s abilities to manage emotions, socialize, and demonstrate self-control (Petrides et al. 2007). Unlike ability EI, which is assessed with performance measures, trait EI is assessed with self-report measures (Petrides et al. 2016; Siegling et al. 2015). Because it is distinct from HEXACO, it could contribute uniquely to compassion. Generally, those with high trait EI see themselves as flexible, optimistic, and empathetic (Petrides and Furnham 2001). In addition, trait EI has been linked to accurate emotion perception and other-reported prosocial behaviour (Mavroveli et al. 2009), suggesting a link with compassion.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relations between compassion for others with personality traits and how these might vary in different cultural contexts—specifically, Canada and Spain. These contexts are distinct in key aspects; for example, Canada is more individualistic (versus collectivistic) than Spain, indicating that relationships are less tight-knit, and individuals are expected to take care of themselves (Hofstede et al. 2010). Spanish culture has a higher power distance (the importance of social hierarchies) and much higher uncertainty avoidance (how well a culture tolerates unknowns; Hofstede et al. 2010). However, we opted not to make specific hypotheses about compassion cross-culturally, as broad cultural values are not necessarily deterministic of individual traits. Importantly, Canada and Spain also possess similarities that make them ideal for cross-cultural comparison. Most notably, they are similarly heterogeneous, with about 21% and 13% of Canada and Spain’s populations, respectively, being foreign-born nationals (Statistics Canada 2017; United Nations 2017).

Method

Participants

We obtained data from Canadian and Spanish adults. In Canada, 590 undergraduate students at a large Ontario university were recruited. These participants were compensated with academic course credit. Of these students, 139 (25.0%) were male, 415 (74.8%) were female, and one participant identified as transgender. Participants ranged in age from 17 to 37 years, with a mean age of 18.34 (SD = 1.48). Thirty-five participants were excluded due to missing data. Spanish participants were 372 adults recruited from the personal networks of students attending the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (National Distance Education University; UNED). Students were compensated with course credits for recruiting these participants. A total of 226 (60.8%) participants were women, and 144 (38.7%) were men. The age range was 17 to 68 years, with a mean age of 38.92 (SD = 11.97). Two participants were removed for missing data. Both studies received ethical approval from the respective universities. Participation was fully voluntary, and participants could withdraw from the study at any time.

Procedure

All materials were administered online. Participants read the letter of information and provided their consent to participate. Canadian participants accessed the study via a university recruitment database and completed all questionnaires on the Qualtrics survey platform, while Spanish participants were emailed a link to the survey and completed it on the Google Questionnaire platform. Measures were presented in a randomized series to control for order effects. Upon completion, participants read a debriefing letter.

Measures

The Compassion Scale (Pommier 2011)

We employed a relatively new measure of compassion, Pommier’s (2011) Compassion Scale, which is based on the six-factor structure of Neff’s (2003) Self-Compassion measure. Pommier found evidence for this structure in a sample of American students, which has more recently been replicated in a community sample of adults (Sousa et al. 2017). It has been suggested that a two-general factor solution (compassion and disconnectedness, or pro- and con-trait compassion) is ideal for the Self-Compassion and Compassion scales (Brenner et al. 2017; Coroiu et al. 2018; Sousa et al. 2017), rather than a unidimensional score.

Pommier’s (2011) Compassion Scale is a 24-item measure composed of kindness, mindfulness, and the recognition of common humanity factors in addition to their opposites indifference, disengagement, and separation, which are represented by two higher-order factors of compassion and disconnectedness (Sousa et al. 2017). The scale has demonstrated good psychometric validity as well as test-retest and internal consistency reliabilities (Pommier 2011; Sousa et al. 2017). Items (e.g. “I tend to listen patiently when people tell me their problems”) are responded to on a 5-point Likert scale. For this study, excellent internal consistency was found for two factors of compassion, α = 0.84, and disconnectedness, α = 0.89.

Because the Compassion Scale is relatively new, we did not locate an adapted or translated version in the published literature, which is required to expand research in a wider context. Following the guidelines proposed by the International Test Commission (2017) and extensively described elsewhere (e.g. Hambleton and Lee 2013), the scale was translated into Spanish by a fully bilingual collaborator. To ensure construct equivalence with the English version, it was then back-translated, reviewed, and items were adjusted for meaning where necessary. Compassion and disconnectedness demonstrated internal reliabilities of α = 0.81 and α = 0.88, respectively.

HEXACO-60 (Lee and Ashton 2004)

The HEXACO-60 is a 60-item short version of the HEXACO inventory. Each domain (honesty-humility, emotionality, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience) contains ten items and can be divided into four facets. Items are assessed with a five-point Likert scale. In the Canadian sample, the subscales of the HEXACO revealed good internal consistency: honesty-humility (α = 0.77), emotionality (α = 0.78), extraversion (α = 0.81), agreeableness (α = 0.78), conscientiousness (α = 0.79), and openness (α = 0.75). For the Spanish sample, the Spanish version of the HEXACO-60 was administered. In the Spanish sample, the subscales of the HEXACO revealed good internal consistency: honesty-humility (α = 0.79), emotionality (α = 0.75), extraversion (α = 0.77), agreeableness (α = 0.69), conscientiousness (α = 0.74), and openness (α = 0.74). All versions and translations of the HEXACO can be found at http://hexaco.org/hexaco-inventory.

Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire, Short Form (TEIQue-SF; Petrides 2009a)

The TEIQue-SF is a 30-item short-form version of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue-SF; Petrides 2009a). The TEIQue has demonstrated good reliability (Petrides 2009b), factor structure (Perera 2015), construct validity (Laborde et al. 2016), and predictive validity for adaptive outcomes (Mikolajczak et al. 2009; Petrides et al. 2007; Saklofske et al. 2007), and it is effective at capturing the distinct nature of trait (versus ability) EI (Petrides and Furnham 2001).

The TEIQue-SF assesses self-perceptions of emotional competencies and adaptive dispositions. Example items include “I’m usually able to influence the way other people feel” and “I often pause and think about my feelings”. Responses are assessed on a seven-point Likert scale and items are summed to create a total trait EI score. In the Canadian sample, the TEIQue-SF demonstrated good internal reliability, α = 0.88. The Spanish version of the TEIQue-sf (Petrides et al. 2017) also demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.88).

Data Analyses

All variables were screened for skewness and kurtosis and no problematic deviations were observed. We then conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the Compassion Scale on the Canadian and Spanish data separately to establish support for its factor structure in both samples. Recent evidence has suggested the Compassion Scale should be divided into two factors—compassion and disconnectedness—with its subscales representing six sub-factors (Brenner et al. 2017; Sousa et al. 2017). The CFA suggested that in the Canadian sample, a two-factor model (χ2 (245) = 687.826, p < .001; RMSEA = .057 [.052, .062]; CFI = .908; SRMR = .054) demonstrated better fit than a one-factor model (χ2 (246) = 929.429, p < .001; RMSEA = .071 [.066, .076]; CFI = .858; SRMR = .072), χ2diff (1) = 241.603. This was also found for the Spanish sample, χ2diff (1) = 75.613, such that a two-factor solution (χ2 (245) = 616.717, p < .001; RMSEA = .064 [.058, .070]; CFI = .874; SRMR = .057) demonstrated better fit than one factor (χ2 (246) = 692.330, p < .001; RMSEA = .070 [.064, .076]; CFI = .849; SRMR = .066).

To investigate the cross-cultural invariance of the Compassion Scale, we also conducted multigroup CFAs for configural, metric, and scalar invariance with the two-factor model of the Compassion Scale. Three multigroup CFAs were conducted with different parameter restrictions using the lavaan package for R (see Table 1 for fit indices). A maximum likelihood estimation was used for all CFAs. Results suggested that participants’ patterns of responding to the Compassion Scale differ between Canada and Spain, thus limiting the ability to directly compare group means between Canadian and Spanish participants.

We conducted a two-by-two ANOVA to investigate whether compassion and disconnectedness differed by gender and culture. The samples were then examined separately using bivariate correlation analyses to reveal the zero-order correlations between age and personality variables with compassion and disconnectedness. Stepwise multiple regressions were then conducted with both compassion and disconnectedness as outcomes in the Canadian and Spanish samples separately. Listwise deletion was used to account for missing data. In each case, gender was controlled by entering it at step 1, followed by the HEXACO factors and trait EI in step 2 in order to ascertain which personality variables were the most meaningful predictors of compassion.

Results

Demographic Differences

Table 2 presents mean scores and standard deviations for the study variables in the two samples. A 2 × 2 (culture by gender) ANOVA of compassion scores revealed significant main effects of gender, F (1, 920) = 51.34, p < .001, η2 = .05, and culture, F (1, 920) = 23.21, p < .001, η2 = .02, but no interaction effect, F (1, 920) = .04, p = .85, η2 = .00. Men reported lower compassion than women, and Canadian participants reported lower compassion than their Spanish counterparts. This was the case for disconnectedness as well, with significant main effects of gender, F (1, 920) = 47.70, p < .001, η2 = .05, and culture, F (1, 920) = 33.80, p < .001, η2 = .03, but no interaction effect, F (1, 920) = .20, p = .66, η2 = .00. Men reported higher disconnectedness than women, and Canadian participants reported higher disconnectedness than Spanish participants. However, the findings on cross-cultural differences in compassion scores must be interpreted cautiously due to the lack of measurement invariance found for the Compassion Scale. Age was unrelated to compassion and disconnectedness in the Canadian sample (r = .01, p = .885 and r = − .01, p = .891, respectively) as well as in the Spanish sample (r = − .02, p = .717 and r = .01, p = .877).

Bivariate Correlations

Correlational analyses (see Table 3) indicated that HEXACO factors and trait EI were related to compassion (positively) and disconnectedness (negatively). Most of these relations were medium in size (Cohen 1988). Agreeableness and openness had the weakest relations with compassion, while emotionality and trait EI had the strongest relations. Agreeableness and openness also had the weakest relations with disconnectedness, while honesty-humility, emotionality, and trait EI were most strongly related.

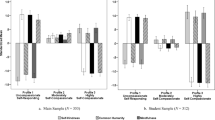

Canadian Sample

Honesty-humility, emotionality, agreeableness, and trait EI were significant, positive predictors of compassion. As well, conscientiousness and openness demonstrated an unanticipated relation with compassion. Extraversion had no relation. Emotionality was the strongest predictor of compassion among Canadians, accounting for 9% of variance. In the second model, honesty-humility, emotionality, extraversion, agreeableness, trait EI—and again, unexpectedly, openness—were significantly related to disconnectedness. However, extraversion and openness’s contributions were negligible, accounting for less than 1% of variance each. Emotionality was again the strongest predictor, contributing 15% of unique variance. Tables 4 and 5 depict the results of the regression analyses.

Spanish Sample

The results of the analyses in the Spanish sample diverged somewhat from the Canadian sample. Emotionality and trait EI again predicted compassion, accounting for 10% and 6% of the variance in compassion scores respectively. Openness was also unexpectedly related to compassion. However, no relations were found with honesty-humility, extraversion, or agreeableness. Disconnectedness was significantly related to honesty-humility, emotionality, and trait EI, but not to agreeableness or extraversion. Its strongest relations were with emotionality and trait EI, with each explaining 7% of the variance. Tables 6 and 7 depict the results of the regression analyses.

Discussion

The present research sought to identify the personality variables linked to compassion and explore how they might differ between Canadian and Spanish cultures. Compassion is characterized by the ability to recognize, feel concern for, and be motivated to alleviate suffering in others, and it is a personal strength predicting a range of positive outcomes. Given the prosocial nature of compassion, we expected trait EI and the HEXACO domains of honesty-humility, emotionality, extraversion, and agreeableness would be positively correlated with compassion scores.

We found gender effects consistent with previous literature (Pommier 2011; Sinclair and Saklofske 2018; Sousa et al. 2017) such that Canadian and Spanish women reported higher compassion and lower disconnectedness than their male counterparts. In fact, the size of this difference was almost identical; Canadian and Spanish women, respectively, scored on average 0.25 and 0.26 points higher on compassion, and 0.31 and 0.34 points lower on disconnectedness.

To summarize the personality effects, we found evidence for the influence of emotionality, trait emotional intelligence, honesty-humility, and to a lesser extent, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness. Extraversion demonstrated no relation with compassion or disconnectedness in the Spanish sample and a negligible effect on compassion (but not disconnectedness) in the Canadian sample. Emotionality and trait EI were strong predictors of compassion (positively) and disconnectedness (negatively) in both cultures. However, in the Canadian sample, honesty-humility and agreeableness were significant contributors to both compassion and disconnectedness as well, whereas in the Spanish sample, honesty-humility correlated negatively only with disconnectedness, and agreeableness had no effect on either. The differential findings for compassion and disconnectedness underscore the need to measure these dimensions separately.

While there were some cultural differences, the most powerful predictors overwhelmingly were emotionality and trait EI; importantly, they accounted for a significant amount of variance in both the compassion and disconnectedness factors. Individuals high in emotionality can be described as vulnerable and sensitive (Ashton et al. 2014). As the Compassion Scale contains items like “My heart goes out to people who are unhappy” (Pommier 2011), sensitivity to others’ distress seems to produce higher compassion. Additionally, emotionality contains sentimentality, representing the tendency to feel emotionally attached to others, implying a capacity for other-directed concern. It does not appear that emotionality’s reactivity content—specifically the fearfulness and anxiety facets—precludes emotionality from facilitating compassion.

Trait EI was the second most powerful unique predictor, particularly in the Spanish sample, where it accounted for 6% of the unique variance in compassion and 7% in disconnectedness (compared with 2% of each among Canadians). Trait EI represents a collection of self-perceptions regarding intra- and interpersonal skills, and several aspects of trait EI likely contribute to compassion, including emotional perception and trait empathy (necessary for recognizing and understanding others’ distress), emotion regulation and stress management (likely precursors to mindfulness, described as the ability to feel concern without detachment or personal distress), and relationships (the ability to bond with others and have fulfilling connections; Petrides and Furnham 2001). Future research could explore which unique aspects of trait EI most strongly influence compassion by employing the long-form TEIQue or other EI measures.

Extraversion has been linked with empathy in past research, but this was not the case with compassion in the current study. One explanation for this might be discrepancies between HEXACO’s extraversion versus the five-factor NEO-PI-R (Costa and McCrae 1992). NEO-PI-R’s extraversion contains facets of interpersonal warmth, while HEXACO measures extraversion as a combination of boldness, sociability, liveliness, and self-esteem (Ashton et al. 2004; Ashton et al. 2014). Warmth could be the primary driver of the five-factor model extraversion’s relation with prosocial variables (Nettle 2007; Wakabayashi and Kawashima 2015). Additionally, it is unclear why the relations with agreeableness were relatively weak, given the variable’s prosocial connotations and its links with empathy. One possibility is that agreeableness is also characterized by conflict avoidance or even obedience (e.g. Bègue et al. 2015), traits which are theoretically unrelated to compassion.

The small relation with openness was unexpected and, interestingly, manifested only with compassion (not disconnectedness). Openness is characterized by aesthetic appreciation, inquisitiveness, creativity, and unconventionality (Lee and Ashton 2004). At a glance, these qualities do not seem relevant to compassion. However, given that artistic endeavours are often a process of emotional expression, having a degree of sensitivity might go together with high openness. It could also be argued that the unconventionality facet, which contains items such as “I like people who have unconventional views,” implies non-judgmental acceptance and interconnectedness.

Personality accounted for a slightly higher percentage of variance in the Canadian sample. The predictors explained 37% and 47% of variance in compassion and disconnectedness in Canada, but 35% and 40% of variance, respectively, in Spain. One explanation for this discrepancy might be found in cultural value dimensions. Geert Hofstede’s (2011) individualism-collectivism axis is likely most pertinent for compassion research; for example, Bengtsson et al. (2016) found that the relation between compassion for others and for the self is stronger in more collectivistic societies, suggesting that cultural collectivism plays a role in determining how compassion manifests. This link makes theoretical sense given the collectivistic emphasis on interpersonal harmony; notably, Canada is much less collectivistic than Spain (Hofstede 2001; Hofstede et al. 2010). In an individualistic culture, the development of compassion might rely more on individual differences, while in a collectivist culture, it might be driven by shared cultural values. In fact, some researchers have gone as far as arguing that personality itself is “less apparent in collectivistic cultures... because the situation is such a powerful determinant of social behaviour” (Triandis 1995, p.74). Future research should endeavour to expand on this possibility regarding compassion by recruiting samples from highly collectivistic cultures (e.g. South Korea, China, Mexico, or Chile; Hofstede et al. 2010).

Limitations and Future Directions

While women reported higher compassion scores in both cultures, it should be noted that with personality accounted for, gender’s influence on compassion was small. Additionally, while we found that Spanish participants reported higher compassion than Canadians, the lack of measurement invariance between groups makes this difficult to interpret. Spanish and Canadian adults may respond to the Compassion Scale differently as a result of unique cultural norms, or simply differences in interpretation resulting from the translation process. This research reveals a need to modify or develop a novel scale for compassion that is comparable across distinct cultures. Alternatively, compassion as a construct could simply mean different things in different cultures—perhaps indicating a need for culture-specific measures of compassion.

The Spanish sample contained a much wider age range than our Canadian sample, due to differences in recruitment strategy. While it is conceivable that compassion increases with age, given that some evidence has suggested empathy and prosocial tendencies are higher in older populations (Beadle et al. 2015; O’Brien et al. 2013; Richter and Kunzmann 2011), others have found that older adults have a diminished capacity for empathy (Bailey et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2014). Here, a correlational analysis found that age had no relation with compassion. We did not collect data on participants’ occupation or socioeconomic status, but these could be other characteristics that influence the presentation of compassion. Possible research directions are thus how compassion develops across the lifespan, how it might manifest in different professions, or how it varies across socioeconomic groups.

The study’s use of self-report measures means that the study suffers from common method bias—that is the presence of variance that is due to measurement error in the instrument, rather than actual variations among the participants (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Additionally, some researchers have discussed how successfully questionnaires can be compared across cultures. For example, Melchers et al. (2016) questioned whether there are real cross-cultural differences in personality, or whether these are driven mostly by response biases; furthermore, it is unclear whether differences are products of cultural influence (as some traits are valued differently across cultures; Melchers et al. 2016) or have a genetic component. Another limitation is this study’s focus on compassion for others. Compassion can also be directed at the self and received from others, and these motivations may have distinct origins as well as cross-cultural manifestations. Future studies could investigate these motivations and their associations with personality.

References

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2001). A theoretical basis for the major dimensions of personality. European Journal of Personality, 15, 327–353. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.417.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868306294907.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & de Vries, R. E. (2014). The HEXACO honesty-humility, agreeableness, and emotionality factors: a review of research and theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314523838.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., Perugini, M., Szarota, P., de Vries, R. E., Di Blas, L., Boies, K. & de Raad, B. (2004). A six-factor structure of personality-descriptive adjectives: solutions from psycholexical studies in seven languages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 356–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.356.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., Visser, B. A., & Pozzebon, J. A. (2008). Phobic tendency within the five-factor and HEXACO models of personality structure. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 734–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.10.001.

Bailey, P. E., Henry, J. D., & Von Hippel, W. (2008). Empathy and social functioning in late adulthood. Aging & Mental Health, 12, 499–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802224243.

Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000022607.19833.00.

Beadle, J. N., Sheehan, A. H., Dahlben, B., & Gutchess, A. H. (2015). Aging, empathy, and prosociality. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbt091.

Bègue, L., Beauvois, J. L., Courbet, D., Oberlé, D., Lepage, J., & Duke, A. A. (2015). Personality predicts obedience in a Milgram paradigm. Journal of Personality, 83(3), 299–306.

Bengtsson, H., Söderström, M., & Terjestam, Y. (2016). The structure and development of dispositional compassion in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 36, 840–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431615594461.

Brenner, R. E., Heath, P. J., Vogel, D. L., & Credé, M. (2017). Two is more valid than one: Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64, 696–707. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000211.

Brill, M., & Nahmani, N. (2017). The presence of compassion in therapy. Clinical Social Work Journal, 45, 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-016-0582-5.

Chen, Y.-C., Chen, C.-C., Decety, J., & Cheng, Y. (2014). Aging is associated with changes in the neural circuits underlying empathy. Neurobiology of Aging, 35, 827–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.10.080.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Collins, M. E., & Garlington, S. (2017). Compassionate response: intersection of religious faith and public policy. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 36, 392–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2017.1358127.

Coroiu, A., Kwakkenbos, L., Moran, C., Thombs, B., Albani, C., Bourkas, S., Zenger, M., Brahler, E., & Körner, A. (2018). Structural validation of the Self-Compassion Scale with a German general population sample. PLoS One, 13(2), Article e0190771. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190771.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. (1992). Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five factor model (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odesa: Psychological Assessment Center.

Del Barrio, V., Aluja, A., & Garcia, L. F. (2004). Relationship between empathy and the big five personality traits in a sample of Spanish adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality, 32, 677–682. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2004.32.7.677.

Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Cruz, B. (2016). Relationships between nurses’ empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 60, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015.

Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365–376.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. A. (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013262.

Gaughan, E. T., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2012). Examining the utility of general models of personality in the study of psychopathy: a comparison of the HEXACO-PI-R and NEO PI-R. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26, 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.513.

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D. K., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018807.

Graziano, W. G., & Eisenberg, N. (1997). Agreeableness: a dimension of personality. In R. Hogan, J. Johnson, & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 795–824). San Diego: Academic Press.

Gu, J., Cavanagh, K., Baer, R., & Strauss, C. (2017). An empirical examination of the factor structure of compassion. PLoS One, 12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172471.

Hambleton, R. H., & Lee, M. K. (2013). Methods for translating and adapting tests to increase cross-language validity. In D. H. Saklofske, V. L. Schwean, & C. R. Reynolds (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of child psychological assessment (pp. 172–181). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: software of the mind (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion, 8, 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013237.

International Test Commission. (2017). The ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests (2nd ed). Retrieved from: www.InTestCom.org

Kirby, J. T., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48, 778–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003.

Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Lamm, C., & Singer, T. (2012). Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cerebral Cortex, 23, 1552–1561. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhs142.

Laborde, S., Allen, M. S., & Guillen, F. (2016). Construct and concurrent validity of the short-and long-form versions of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 232–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.009.

Lama, D. (1995). The power of compassion. New Delhi: HarperCollins.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioural Research, 39, 329–358. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3902_8.

Leiberg, S., Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2011). Short-term compassion training increases prosocial behavior in a newly developed prosocial game. PLoS One, 6, e17798. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017798.

Lim, D., Condon, P., & DeSteno, D. (2015). Mindfulness and compassion: an examination of mechanism and scalability. PLoS One, 10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118221.

Lim, D., & DeSteno, D. (2016). Suffering and compassion: the links among adverse life experiences, empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior. Emotions, 16, 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000144.

Mavroveli, S., Petrides, K. V., Sangareau, Y., & Furnham, A. (2009). Exploring the relationships between trait emotional intelligence and objective socio-emotional outcomes in childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X368848.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81.

Melchers, M. C., Li, M., Haas, B. W., Reuter, M., Bischoff, L., & Montag, C. (2016). Similar personality patterns are associated with empathy in four different countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00290.

Mikolajczak, M., Petrides, K. V., Coumans, N., & Luminet, O. (2009). The moderating effect of trait emotional intelligence on mood deterioration following laboratory-induced stress. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 9, 455–477.

Mongrain, M., Chin, J. M., & Shapira, L. B. (2011). Practicing compassion increases happiness and self-esteem. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 963–981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9239-1.

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390129863.

Nettle, D. (2007). Empathizing and systemizing: What are they, and what do they contribute to our understanding of psychological sex differences? British Journal of Psychology, 98, 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712606X117612.

O’Brien, E., Konrath, S. H., Grühn, D., & Hagen, A. L. (2013). Empathic concern and perspective taking: linear and quadratic effects of age across the adult life span. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs055.

Oman, D. (2011). Compassionate love: accomplishments and challenges in an emerging scientific/spiritual research field. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 14, 945–981. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.541430.

Pace, T. W. W., Negi, L. T., Adame, D. D., Cole, S. P., Sivilli, T. I., Brown, T. D., Issa, M. J., & Raison, C. L. (2008). Effect of compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune and behavioral responses to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.011.

Perera, H. N. (2015). The internal structure of responses to the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire–short form: an exploratory structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97, 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1014042.

Petrides, K. V. (2009a). Technical manual for the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue). London: London Psychometric Laboratory.

Petrides, K. V. (2009b). Psychometric properties of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue). In C. Stough, D. H. Saklofske, & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), Assessing emotional intelligence: theory, research, and applications (pp. 85–101). New York: Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-88370-0_5.

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15, 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.416.

Petrides, K. V., Gómez, M. G., & Pérez-González, J.-C. (2017). Pathways into psychopathology: modelling the effects of trait emotional intelligence, mindfulness, and irrational beliefs in a clinical sample. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24, 1130–1141. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2079.

Petrides, K. V., Pita, R., & Kokkinaki, F. (2007). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. British Journal of Psychology, 98, 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712606X120618.

Petrides, D., Siegling, A., & Saklofske, D. H. (2016). Theory and measurement of trait emotional intelligence. In U. Kumar (Ed.), Wiley handbook of personality assessment (pp. 90–103). New Jersey: John Wiley.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Pommier, E. A. (2011). The compassion scale. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 72, 1174.

Poortinga, Y. H., & Van Hemert, D. A. (2001). Personality and culture: demarcating between the common and the unique. Journal of Personality, 69, 1033–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696174.

Richter, D., & Kunzmann, U. (2011). Age differences in three facets of empathy: performance-based evidence. Psychology and Aging, 26, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021138.

Saklofske, D. H., Austin, E. J., Galloway, J., & Davidson, K. (2007). Individual difference correlates of health-related behaviors: preliminary evidence for links between emotional intelligence and coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.08.006.

Shepherd, S., & Belicki, K. (2008). Trait forgiveness and traitedness within the HEXACO model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.05.011.

Siegling, A. B., Saklofske, D. H., & Petrides, K. V. (2015). Measures of ability and trait emotional intelligence. In G. J. Boyle, D. H. Saklofske, & G. Matthews (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychology constructs (pp. 381–414). San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press.

Sinclair, S., Beamer, K., Hack, T. F., McClement, S., Raffin, S. B., Chochinov, H. M., & Hagen, N. A. (2017). Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: a grounded theory study of palliative care patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliative Medicine, 31, 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316663499.

Sinclair, V. M., & Saklofske, D. H. (2018). Is there a place in politics for compassion? The role of compassion in predicting hierarchy-legitimizing views. Self and Identity, 18, 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1468354.

Sousa, R., Castilho, P., Vieira, C., Vagos, P., & Rijo, D. (2017). Dimensionality and gender-based measurement invariance of the Compassion Scale in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 182–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.003.

Sprecher, S., & Fehr, B. (2005). Compassionate love for close others and humanity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 629–651.

Statistics Canada. (2017). Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: key results from the 2016 Census. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-eng.htm

Steindl, S. R., Kirby, J. N., & Tellegen, C. (2018). Motivational interviewing in compassion-based interventions: theory and practical applications. Clinical Psychologist, 22(3), 265-279. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12146.

Steindl, S. R., Yiu, R. X. Q., Bauman, T., & Matos, M. (2019). Comparing compassion across cultures: similarities and differences among Australians and Singaporeans. Australian Psychologist, 55(3), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12433.

Strauss, C., Taylor, B. L., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F., & Cavanagh, K. (2016). What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder: Westview Press.

United Nations. (2017). International migration report. Retrieved from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2017_Highlights.pdf

Wakabayashi, A., & Kawashima, H. (2015). Is empathizing in the E-S theory similar to agreeableness? The relationship between the EQ and SQ and major personality domains. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.030.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VS designed the study, oversaw participant recruitment for the Canadian sample, collaborated in conducting data analyses, and wrote the majority of the manuscript. GT oversaw participant recruitment for the Spanish sample, oversaw translation of materials for the Spanish sample, collaborated in conducting data analyses, and collaborated in writing and editing the final version of the manuscript. DS collaborated with the design of the study, collaborated in conducting data analyses, and collaborated in writing and editing the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants

All human studies have been approved by either the Western University’s Research Ethics Board or the ethics committee of the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (National Distance Education University; UNED), and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sinclair, V.M., Topa, G. & Saklofske, D. Personality Correlates of Compassion: a Cross-Cultural Analysis. Mindfulness 11, 2423–2432 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01459-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01459-7