Abstract

Objectives

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), an intervention that integrates mindfulness with cognitive-behavioral therapy, is an 8-week program originally developed to prevent relapses in patients with depression. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of MBCT for preventing relapse, but few studies have evaluated MBCT in naturalistic conditions with real-world samples. Therefore, we sought to explore the characteristics and experiences of individuals receiving MBCT in primary care.

Methods

Mixed-methods approach combining descriptive and qualitative data. Quantitative data were obtained from 269 individuals from different socioeconomic backgrounds who participated in an MBCT program in our healthcare area during the years 2017 and 2018. Qualitative data were obtained from a subsample of participants who agree to participate in semi-structured individual interviews. An interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach was used to analyze the qualitative data.

Results

In the whole sample (n = 269), the most commonly diagnosed disorders were adjustment (41.6%), mood (22.7%), and anxiety (14.1%). Most participants (60%) were taking psychotropic medications (mainly antidepressants). Overall, mindfulness training improved depressive and anxiety symptoms, regardless of the specific diagnosis. A subsample of 14 individuals participated in the qualitative study. Four overarching themes emerged from the IPA analysis in this subsample: (1) effects of mindfulness practice, (2) learning process, (3) group experience, and (4) mindfulness in the healthcare system.

Conclusions

The findings of this naturalistic, mixed-methods study suggest that MBCT could be an effective approach to treating the symptoms of common mental disorders in the primary care setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For the last 30 years, mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been extensively used to treat both physical and mental health problems. Numerous studies support the use of mindfulness meditation to improve the symptoms of the most prevalent mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and addictive disorders (Goldberg et al. 2018; Khoury et al. 2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is a treatment program developed to prevent depression relapse (Segal et al. 2002). MBCT combines cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness practices to teach participants to become more aware of the feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations associated with depressive relapse (Segal et al. 2002). The efficacy of MBCT in preventing relapses in depression has been well established by several randomized controlled trials (RCTs; Kuyken et al. 2015; Piet and Hougaard 2011; Teasdale et al. 2000; Segal et al. 2010). Recently, an individual patient meta-analysis from RCTs suggested that people receiving MBCT had a reduced risk of depressive relapse within a 60-week follow-up period compared with those who did not receive MBCT (Kuyken et al. 2016).

The evidence from RCTs to support MBCT has been complemented by several qualitative studies that have explored the experience of patients who participated in MBCT groups. For example, Mason and Hargreaves (2001) interviewed patients with depressive disorder, finding that the initial expectations for the practice of mindfulness were highly relevant; in that study, participants with open, flexible expectations reported fewer barriers to the intervention than patients with rigid expectations and those looking for an external solution to their problems. That study also highlighted the key role of the group setting to enable skill acquisition and generalization, and the importance of accepting the experience. Finucane and Mercer (2006) reported that, for most patients, forming part of a group was a valuable normalizing experience. Although most of the participants in that study felt that the intervention was too short and that follow-up was needed, most of the participants continued to practice mindfulness on their own even 3 months after the group therapy had finished (Finucane and Mercer 2006). Allen et al. (2009) interviewed 20 individuals 12 months after they had completed an MBCT program to determine the specific components of MBCT that the participants had found to be most helpful and meaningful. In that study, the two main benefits of MBCT according to participants were (1) a greater control over depression and (2) greater acceptance of negative thoughts and feelings. Participants also reported finding it difficult to make time to practice without the support of the group (Allen et al. 2009). Despite the valuable evidence provided by those studies, the major limitation is that most were conducted as a part of an RCT consisting mostly of participants with major depressive disorder, thereby limiting the generalization of those findings to MBCT delivered in other settings or to patients with other health-related problems.

One of the major challenges faced by MBCT is related to its accessibility and implementation. Published data show that access to MBCT remains limited and, despite the large body of research supporting the clinical value of this program, MBCT still remains underutilized in real-world mental healthcare. This problem is not exclusive to MBCT, as most of the evidence on the efficacy of MBIs in general comes from RCTs in which mindfulness was applied to well-defined, homogenous clinical populations. Dimidjian and Segal (2015) estimated that less than 1% of mindfulness research is focused on implementation or effectiveness. In the UK, the few studies conducted to date show that implementation of MBCT varies substantially among healthcare providers and is greatly dependent on the presence of committed individuals and organizational support (Crane and Kuyken, 2012; Rycroft-Malone et al. 2017). Outside the UK, data on the implementation of MBCT programs are even scarcer, suggesting that MBCT is little used in other countries. Moreover, scant research has been performed to investigate the application of MBCT in real-world settings (such as primary care) in which a wide variety of psychiatric symptoms and disorders—including depressive, anxiety, and adjustment stress-related disorders—are common (Roca et al. 2009). However, one such study conducted in Sweden compared MBI with TAU (mainly individual cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) in the primary care setting, finding that mindfulness was non-inferior to individual-based therapy for patients with depression, anxiety, or stress-adjustment disorders (Sundquist et al. 2015). The use of MBIs in primary care populations is supported by the Sundquist et al. (2015) study and by a meta-analysis of six trials that evaluated the effects of MBIs in adults in primary care settings, which concluded that MBIs are efficacious for improving mental health and quality of life in this population (Demarzo et al. 2015b).

The present study evaluates the value of MBCT delivered in a primary care setting in Spain. MBCT was delivered as part of an innovative primary care support program developed to increase access to mental healthcare services in Barcelona (Spain). Given the novel nature of this program within the public primary care system, it was considered important to collect data on the characteristics and experiences of the participants in order to evaluate the impact of the program on symptoms and to assess perceived acceptability of the intervention. In this exploratory study, we used a mixed-methods approach involving a quantitative description of the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants combined with qualitative data from in-depth interviews. These interviews were conducted 3 months after completion of the course and the data obtained from these interviews were evaluated using the interpretative phenomenological analysis approach (IPA), a technique that focuses on the subjective experience of the individual (Eatough and Smith 2006). Since the individual’s perspective cannot be directly accessed, in IPA, the researcher interprets the participant’s interpretation of his/her own world through a double hermeneutic process (Eatough and Smith 2006), which some researchers consider to be an important advantage of the IPA approach (Parke and Griffiths 2012). This process allows the researcher to reflect on the participant’s insider perspective in the broader context informed by scientific publications and research on the topic/experience under study.

Method

Participants

Data were available from 269 individuals (69.9% women, mean age 46.6, SD = 12.7) who participated in MBCT courses between January 2017 and March 2018. Inclusion criteria for the MBCT program were (1) age > 18 years and (2) DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) criteria for depressive, anxiety, or stress-related (acute-stress disorder and adjustment disorder) disorders. Diagnoses were based on the judgment of experienced clinical psychologists or psychiatrists. The presence of comorbidities, pain-related disorders, and the use of psychotropic medications were not considered exclusion criteria for participation in the MBCT. Individuals who met DSM-5 criteria for any of the following disorders were excluded from participation in the MBCT: bipolar, eating, post-traumatic stress, psychotic, or borderline personality disorder. Similarly, individuals with current substance abuse or suicidality were also excluded. Clients presenting either of these diagnoses were referred to specialized mental health services for treatment. None of the participants had any prior experience with mindfulness practice.

The participants were evenly distributed in terms of educational level: one-third had completed elementary education, one-third had completed high school, and one-third had graduated from college. Most participants (53.5%) were employed. According to the clinical records, the most common disorders in this sample were adjustment disorders (41.6%), followed by mood (22.7%) and anxiety disorders (14.1%). More than half of the participants (n = 160, 59.5%) were receiving pharmacological treatment, mainly antidepressants (53.5%) and benzodiazepines (27.1%). A complete description of the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample is provided in Table 1.

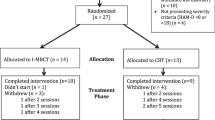

Of the 269 individuals who participated in MBCT groups in this period, 66 (24.5%) dropped out of the program. Of those 66 participants, 39.6% did not give any explanation for their decision to withdraw (see Table 2 for details). Participants whose MBCT program finalized in October or November 2017 were contacted 3 months after course completion and invited to participate in the qualitative study. To obtain a wide range of participant experiences, we identified an initial group of 30 potential participants based on their participation rate in the eight-session MBCT program, inviting participants (10 per group) with low (1–3 sessions), intermediate (4–6 sessions), and high (7–8 sessions) attendance at the MBCT. We attempted to contact these 30 individuals by telephone to explain the study aims and invite them to participate; however, we were only able to reach 22 of the potential participants by telephone. Of these, 14 agreed to participate. Of the eight individuals who did not participate in the qualitative interview, six were unable to do so due to prior personal or work commitments and two were not interested. Figure 1 provides a description of the flow of participants through the qualitative study. Fourteen participants, mainly women (n = 9), participated in the qualitative study. The mean age was 49.7 years (SD = 7.28). At the time of the interview, most participants (n = 10) were employed. Most (n = 8) had completed high school. The mental health-related diagnoses in this subsample were adjustment disorder (n = 9), anxiety disorder (n = 4), and major depressive disorder (n = 1). Most of the participants in the subsample (12/14; 86%) had attended ≥ six of the eight MBCT sessions, distributed as follows: eight sessions (n = 2), seven sessions (n = 8), six sessions (n = 2), and four sessions (n = 2). At the time of the qualitative interview, 57.1% (8/14) of the participants reported practicing mindfulness at the following frequencies: once weekly (n = 3), three times a week (n = 4), or every day (n = 1); the other six participants did not practice mindfulness.

Despite the relatively small number of participants in the qualitative subsample (n = 14), the sample size was considered adequate according to IPA guidelines given the comprehensive nature of the interviews (Smith et al. 2009). Participation was voluntary and all participants signed an informed consent form.

Procedure

The socio-demographic characteristics and mental health diagnoses of the sample were obtained from clinical records and through a comprehensive interview with a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist. Symptoms were evaluated with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), which were completed before and after the 8-week treatment program. Attendance at the MBCT sessions was recorded.

Before the qualitative interview, participants were asked to complete an ad hoc questionnaire containing questions on socio-demographic data (age, sex, level of education, marital status) and a series of additional questions, including the following two specific questions about mindfulness practice: (1) “Have you practiced mindfulness during the past month?” and if so, (2) “How often?” The survey also included the following statements: (1) “Please indicate how satisfied you are with the MBCT program (1 = very unsatisfied to 5 = very satisfied)” and (2) “Please indicate how likely you are to recommend MBCT to someone facing similar problems as you (1 = I would absolutely not recommend it, to 5 = I would absolutely recommend it).”The clinical interview, which lasted from 45 to 60 min, was designed to gather information about the following: (1) participants’ experience with mindfulness training and (2) their experience with and opinion about implementing the MBCT program within the primary care system. The main topics covered during the interview, together with examples of the open-ended questions, are shown in Table 2. Following IPA guidelines (Smith et al. 2009), the participants were encouraged to express themselves freely; when necessary, the researcher asked for additional clarification. The researcher strove to maintain an open attitude towards the participants’ views, allowing them to express their opinions as naturally as possible.

Context

The Institute of Neuropsychiatry and Addictions (INAD) of the Barcelona Mar Health Park (PSMAR) is one of the first mental health trusts to implement MBCT in the public healthcare system in Catalonia. The INAD is located in the Barcelona metropolitan area, a healthcare area covering over 900,000 inhabitants and approximately 40% of the mental healthcare needs for the city of Barcelona. The INAD provides mental healthcare support for 15 primary care centers in the coastal region of Barcelona. The organization and delivery of mental healthcare involves biweekly visits by a clinical psychologist and a psychiatrist to the primary care center to meet with general practitioners (GP) to discuss cases and for clinical visits with patients. Since 2017, patients from the primary care centers in our coverage area are referred for MBCT when appropriate. Patients presenting mood or stress-related conditions who need further assistance are referred to the primary care support team for a diagnostic interview. Patient meeting the eligibility criteria for the MBCT and who agree to participate are scheduled for enrolment in the next available group (see Fig. 2 showing the care pathway within the primary care support program). Given the high demand for this program, five separate groups are run simultaneously at different times.

Intervention

MBCT is delivered in weekly sessions of 2.5 h per session over an 8-week period, with a 1-day (6 h) retreat. MBCT (Segal et al. 2002) is derived from two main therapeutic approaches: (1) the mindfulness-based stress reduction program (Kabat-Zinn 1990) and (2) cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Using a variety of different mindfulness exercises and cognitive-behavioral skills, which are practiced both in session and at home, MBCT trains individuals to become more aware of bodily sensations, thoughts, and feelings associated with low mood in order to help them to change how they relate (i.e., in a non-attached manner) to those experiences and feelings. The MBCT teacher (MG) is an experienced clinical psychologist and mindfulness practitioner. At the time the interventions described in the present study were performed, MG was enrolled in the Teacher Training Pathway of the Center of Mindfulness Research and Practice (Bangor University, North Wales).

Measures

Beck Depression Inventory-II

The 21-item BDI-II (Sanz, García-Vera et al. 2005) is designed to assess the severity of depressive symptoms, assessing a range of affective, behavioral, cognitive, and somatic symptoms that are indicative of unipolar depression. Each item contains four responses that reflect increasing levels of depressive symptomatology. Possible scores range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Beck Anxiety Inventory

The BAI (Magán et al. 2008) is a 21-item self-report scale designed to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms, primarily physiological symptoms. Similar to the BDI-II, each item contains four response options. The total possible scores range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented for the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. t tests were used to analyze pre-post-treatment data. The reliable change index (RCI) and clinically significant change (CSC) criteria were calculated for BDI and BAI scores following the procedures described by Jacobson and Truax (1991). Normative data from non-patients were used to establish whether participants achieved remission according to their BDI and BAI scores (Magán et al. 2008; Sanz et al. 2003). The RCI was calculated according to the following formula:

\( \mathrm{RCI}=\frac{X_{\mathrm{pre}}-{X}_{\mathrm{post}}}{S_{\mathrm{diff}}} \), where \( {S}_{\mathrm{diff}}=\sqrt{2^{\ast }{\left(\mathrm{SE}\right)}^2} \) and \( \mathrm{SE}={\mathrm{SD}}^{\ast}\sqrt{1-{r}_{\mathrm{tt}.}} \)

Xpre = group mean at the beginning of treatment

Xpost = group mean at the end of treatment

SE = standard error

SD = standard deviation

Rtt = reliability of the measurement instrument (Cronbach’s alpha)

To be considered responders, patients were required to obtain a difference of ≥ 9.34 and 9.08 on the BDI and BAI, respectively, between the mean pre- and post-treatment values.

The following formula was used (criterion C) to determine cutoff scores for the BDI and BAI:

Using this formula, the cutoff point was 14.30 for BDI scores, and 14.77 for BAI scores. Participants who scored below the respective post-intervention BDI and BAI cutoff scores were considered to have remitted.

In accordance with IPA guidelines (Smith et al. 2009), all clinical interviews were audio recorded, anonymized, and transcribed verbatim in order to facilitate their subsequent analysis. The interviews were read several times and line numbered and then coded by a clinical psychologist. These codes were then grouped into higher order (overarching) themes (Eatough and Smith 2006) by two additional members of the research team. Text passages were either coded into existing terms or, if they did not fit any existing category, a new code was assigned. A team meeting was held to discuss the code list and to merge any codes that the team agreed captured the same theme. Codes were generated using Atlas.ti (version 8.2.2).

Results

Treatment Impact on Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms

Depressive and anxiety symptoms in the overall sample had decreased significantly after completion of the MBCT program, as follows: BDI; pre-treatment: mean = 21.90, SD = 11.91, post-treatment: mean = 13.67, SD = 11.71, p = <.001. BAI; pre-treatment: mean = 19.45, SD = 12.64, post-treatment: mean = 15.04, SD = 11.95, p = <.001. Based on BDI scores, the RCI values indicated that 47.4% of the sample showed a reliable post-intervention change, while only 28.7% showed a reliable improvement in anxiety symptoms (BAI). Using a cutoff score of 14.30 in the BDI, 62.5% of the sample fulfilled criteria for remission. Using a cutoff score of 14.77 for the BAI, 62.2% of the sample was considered to be in the “normal range” for anxiety.

Qualitative Study

Participant Experiences

Before the interview, participants were asked to complete an ad hoc questionnaire to indicate their degree of satisfaction with the program. Most participants were satisfied, as indicated by the mean score of 4.35 on the 5-point scale (range: 1 = not satisfied at all to 5 = very satisfied). In terms of the value of the program to help cope with daily life problems, the mean score of 4.07 (range: 1 = not useful at all, 5 = very useful) indicates that, on average, the participants were satisfied. Most participants (mean score = 4.42) would recommend the program to a friend or acquaintance (range: 1 = I would not recommend the program to 5: I would definitively recommend the program).

Major themes that emerged during the course of interviews included: (1) the effects of mindfulness practice, (2) the learning process, (3) the participants’ experiences within the group, and (4) mindfulness in the healthcare system. These themes are listed in Table 3 and discussed in detail below.

Effects of Mindfulness

Participants reported an increase in present-moment awareness, which is defined as being more connected to the current experience versus being lost in mental activity. An increased awareness of the nature of the mind was also reported, as illustrated by this quotation from one of the participants:

I became aware of my inner dialogue, I somehow knew it was there, but you don’t really get in touch with it until you start to practice (…) The mind wanders, but if you are aware you can come back (Participant 1).

This connection to the present was sometimes related to a deeper sense of calm or relaxation and to an increased appreciation for the important things in life. By contrast, lack of awareness and the activation of the automatic pilot were associated with being disconnected from valued things. For example:

Being aware of the present moment and valuing things one at a time has shown me another way of living because I haven’t been connected to the present, I was always a step ahead (Participant 4).

Some participants also noticed that having greater present-centered awareness positively impacted their mood:

This is important for me not to enter another depression spiral (…). Things are as they are, but they don’t have to impact my mood, I can be outside this spiral (Participant 2).

When you are present, you are not so worried about tomorrow. Today is today, and tomorrow can be different (Participant 7).

Interestingly, the opportunity to disconnect from the automatic pilot was also experienced as a way to gain awareness of unproductive ways of relating to the experience, such as avoidance or distraction.

On one hand, it has been a positive experience (participating in the group) because it has shocked me, I had not questioned myself for a while, avoiding, distracting myself (…) The group was useful to realize how easily this structure could fall apart (…) (Participant 9).

Mindfulness practice was also associated with a deeper ability to experience things in a detached manner, allowing difficult thoughts, feelings, or bodily sensations as part of the experience. The ability to refer to the mind as “the” mind, rather than “my” mind or “I” illustrates this detached stance:

Minds… Oh my god! They do weird things. (…) They jump from one thing to the other all the time (Participant 10).

Interestingly, two participants pointed out that this increase in decentering was not related to being careless or indifferent about relevant things:

Problems are there, I am not talking about resignation. Now I can maintain certain distance (from thoughts), without being indifferent (Participant 2).

I can still be responsible for my work, without being overwhelmed by responsibility (Participant 14).

The development of awareness and decentering (subordinate themes 1 and 2) were also related to some attitudinal changes (subordinate theme 3), particularly an increased capacity for acceptance:

This lump in my throat just disappeared, it went away, I let it go, I let go of the pain I had (Participant 3).

Thoughts are there, they are unavoidable, but I can accept them, receive them and that’s OK (Participant 2).

Learning Process

The second theme was the learning process within the MBCT program. Nine participants reported having had an experience during the program—in most cases around the 2nd or 3rd session—that represented a “before and after”; that is, an inflection point. For example, participant 2 observed an inflection point in session 3, the session that focuses on developing a deeper awareness of the nature of the mind and on paying attention to bodily sensations by practicing the body scan and mindfulness of the breath exercises. That participant made the following comment about the body scan practice:

From the third session on I discovered that not feeling my big toe was OK (…) It changes when you realize that it is not a technique to relax, but to being more focused (Participant 2).

For participant 3, this inflection point occurred in session 5, a session focused on working with difficulties and on learning to accept whatever thought arises in the field of awareness. She reported:

It was just a moment… I let it go and that intense pain that I felt just changed (…). It was a sort of a liberation.

Some participants experienced the first part of the program with anxiety, but also noticed how this lessened over the 8-week period. For instance, participant 5 reported:

At first, I could not stay still, then it started to change.

Several participants found that certain aspects of how the contents of the MBCT were taught helped to facilitate group participation (subordinate theme 2b). Three participants commented on the importance of voluntary participation during the inquiry of the practice. Other participants commented on the teacher’s capacity to refrain from judgments. One participant (2) described the importance of keeping track of the group objective (i.e., learning mindfulness) versus entering into personal narratives:

(The teacher) always went back to the sensations (felt) during the practice. Whenever somebody talked about a personal situation, he redirected the conversation towards the practice (…). That was important to me because it was radically different from other group experiences that I have had in the past, when I didn’t feel comfortable sharing things with other members of the group.

All fourteen participants gave examples of how the support of the group was essential to them, encouraging a sense of “support,” “safety,” and “being comfortable.” For example:

There was a really nice atmosphere (…). People were really nice too, so I felt comfortable (Participant 9).

I don’t usually relax anywhere. Closing my eyes in front of strangers is something I usually don’t do, but I felt relaxed (in the group). I was able to let go, really feeling safe (Participant 11).

Patients also noted that the personal and professional characteristics of the instructor seemed to facilitate the group process. He was described as being “peaceful,” “balanced,” and “inviting.”

Although certain factors, such as the group support and the instructor’s guidance, facilitated engagement with the practice, most of the participants recognized that—ultimately—mindfulness practice is a personal responsibility that depends on the individual (subordinate theme 3c). Concepts such as “taking responsibility,” “integrating it into daily life,” and “being constant” were used to describe the importance of embracing the practice.

This is a personal challenge. If I don’t practice, it is a waste of time and money (…) If I can’t do it for half an hour I could practice less, or do some movements (Participant 8).

The participants also provided examples of how they integrated mindfulness into activities of daily living:

I’ve been trying to practice when I walk. I walk with the sensations and enjoy the walk (Participant 3). Looking at the buildings, a balcony, brushing my teeth, savoring the food I’m eating (Participant 4).

I’ve asked the teacher if I could do the 3-steps-breathing-space at work. He said YES! So, I practice there (Participant 8).

I have not been practicing with the audios, but I think that these were useful to gain awareness. If I am anxious, I take a walk (Participant 14).

Group Experience

All the participants provided positive feedback about the group format. For some, it was a good opportunity to normalize their thoughts, feelings, and how they relate to these, helping them to realize that negative feelings and discomfort are part of a shared human experience.

When you share the experience, it becomes normal (Participant 2).

Participants used words such as “empathy,” “identification,” and “normalization” to refer to certain aspects of the group experience. The importance of listening to others and feeling listened to was also emphasized by several participants.

I knew they (the other participants) were going to understand what has been happening to me because they have all had similar experiences (…). That made me feel safe. You realize you are not alone (…). Each of us has our own baggage, and I empathized (with the others) (Participant 6).

(My type of problems) were much more common than I thought (Participant 14).

For some, this feeling of sharing the experience and identifying with the experiences of other individuals took a while:

At the beginning I felt that the others were not experiencing the same as me (…). There were many people with depression (…), but as the days passed, I started identifying with others” (Participant 4).

Others, in contrast, compared themselves with the other members of the group, finding that their own problems were not as severe as those of other participants.

It was quite a heterogeneous group. Many people had a more difficult situation than mine. There were people who had chronic pain or who were grieving, and I simply went there because of my anxiety (…). I realize that I should be thankful for some things in my life (Participant 1).

Mindfulness in the Healthcare System

All of the participants reported being grateful for having had the opportunity to participate in the MBCT program within the public healthcare system. For instance:

Hearing that mindfulness was offered in the public healthcare system was a good surprise for me (Participant 9).

I want to thank you, because, nowadays, considering how things are in the public healthcare system (…), I am very thankful that you took the time to teach us techniques that can be useful for us. At the end of the program, I was very happy (Participant 11).

Regarding the waiting time between referral and the start of group sessions, most participants found that it was short. However, one participant (#3) felt she had to wait a long time, although she also noted that this perception was probably influenced by the presence of life stressors (her mother’s death) together with her depressive symptoms:

I had to wait for around 6 months (…). It was eternal for me (…) because I was having a difficult time, and I needed help (Participant 3).

For me it wasn’t long (the waiting), because I knew I was going to try something new (Participant 2).

Participants were interviewed 3 months after the end of the program. All participants highlighted the need for weekly or biweekly follow-up, and most expressed a desire to repeat the MBCT program in order to facilitate their commitment to mindfulness practice, to “refresh” the contents of the program, or to “delve more deeply” into the contents. Regarding the format of the groups, participants commented the importance of having different time slots to choose from. Only one participant (#6) commented that he would have preferred smaller groups.

Discussion

The present study used a naturalistic, mixed-methods approach to investigate the characteristics and experiences of individuals with a variety of mental health symptoms who received MBCT in a primary care setting. To gain a true understanding of the participants’ subjective experience and perception of the program, we combined quantitative and qualitative methods to ensure a proper and comprehensive evaluation process to assess how MBCT is received by our target population (Demarzo et al. 2015a).

Our sample was largely representative of the patient profile in primary care, who typically present a range of socioeconomic and clinical backgrounds (Finucane and Mercer 2006; Roca et al. 2009). This heterogeneity was expected given that our group provides mental healthcare for a large proportion of the Barcelona metropolitan area, covering areas with wide differences in educational and socioeconomic characteristics. Overall, the clinical severity profile of the sample was mild to moderate. The most common diagnosis (41.6%) among participants in the MBCT program was adjustment disorder, although mood-related (22.7%) and anxiety disorders (14.1%) were also common. Given that the aim of this study was to describe our real-world practice, the mental health diagnoses reported here were obtained from the clinical records of the participants, which were based on the clinical judgment of experienced clinical psychologist or psychiatrists. The prevalence of the various diagnoses in our sample is consistent with previously reported national (Roca et al. 2009) and international data (Ansseau et al. 2004), which have shown that the most prevalent mental health-related diagnoses among the primary care population are adjustment, anxiety, and mood-related symptoms. Importantly, the MBCT intervention significantly reduced depressive and anxiety symptoms, regardless of the specific diagnosis.

Of the initial 269-patient sample, 75.5% were considered treatment adherent, with a mean attendance rate of 83% (6.64/8 sessions). The dropout rate in our study (24.5%) was higher than those reported in previous studies on MBCT, which have ranged from 14% (Kuyken et al. 20082015) to 19% (Segal et al. 2010). We believe that this difference may be attributable to two main factors. First, those two studies were both randomized controlled trials (Kuyken et al. 20082015; Segal et al. 2010) whereas our naturalistic study was conducted in the context of routine care. Second, as shown in Table 3, of the participants who gave a reason for dropping out, the most frequent cause was an important life event such as returning to work or a medical illness.

The subsample that participated in the qualitative study was composed of individuals who received a high dose of MBCT (most attended ≥ 6 sessions). Moreover, most of these participants (8/14) were still practicing mindfulness 3 months after the intervention. The IPA revealed four overarching themes: (i) effects of mindfulness practice, (ii) learning process, (iii) group experience, and (iv) mindfulness in the healthcare system. The first three themes are similar to those that were reported in previous qualitative studies on MBCT, which have either explored the experience of participants with major depressive disorder (Allen et al. 2009; Finucane and Mercer 2006; Mason and Hargreaves 2001) or other mental health problems (Hertenstein et al. 2012). Most participants reported an increase in present-moment awareness associated with a deeper awareness of the things they valued in life. The participants observed that present awareness—characterized by decentering and acceptance—gave them a new way to relate to experiences. These observations reflect several key learning points in MBCT, including recognizing automatic pilot, switching from the “doing” mode to the “being” mode, and relating to the experience—particularly difficult experiences—in a different way (Teasdale et al. 2000). Previous reports suggest that the effects of MBCT are mediated by an increase in decentering (van der Velden et al. 2015) and compassion (Kuyken et al. 2010); although we did not measure these variables, the experiences of the participants in our study seem to suggest that MBCT influenced these factors.

The second major theme identified in this study was the learning process within the program. Interestingly, nine participants identified an inflection point, generally occurring around weeks three to five, when they started to understand the contents of the program and how it could help them. Weeks three to five are described by Cormack et al. (2018) as the “spectrum stage,” characterized by contrasting experiences in which some individuals reported a sense of “getting” the program. We believe that this finding is relevant because it underscores the fact that learning mindfulness is a process, rather than an “end result” achieved in a set period of time. Teachers should be aware of this process because several studies have found that most of the individuals who drop out of mindfulness interventions tend to do so between the first and second sessions (Elices et al. 2016; Segal et al. 2010), suggesting that the mindfulness approach may, at least initially, appear unrelated to the participant’s aims.

Participants identified several key factors that helped them with the program, including the voluntary nature of the program, an absence of judging by the teacher, and the group support. The teacher’s personal and professional characteristics played an important role in the program according to most participants, a finding that underscores the fundamental importance of the teacher as a role model who embodies the practice (Crane et al. 2012). Good management of group dynamics and the process was also regarded as a relevant aspect, as exemplified by one participant who highlighted the ability of the teacher to set boundaries and to balance the needs of the individuals and the group. Consistent with the findings reported by Allen et al. (2009), participants in our sample identified several personal barriers to mindfulness practice, primarily lack of time and a variable commitment level. As in most previous qualitative studies on MBCT (Allen et al. 2009; Finucane and Mercer 2006; Mason and Hargreaves 2001), the group setting was a key aspect to facilitate the development of mindfulness skills. Sharing the experience in a group setting had a positive impact on most participants, allowing them to normalize their experience and to understand the shared nature of suffering. The impact of the group format in MBIs was recently explored in a qualitative study (Cormack et al. 2018) which found—consistent with our findings—that participants associated the group with safety, equality, and the possibility to communicate one’s experiences freely.

Finally, the participants were encouraged to give their opinion about their perceptions of MBCT offered within the healthcare system. All participants reported feeling grateful for the opportunity to participate in the MBCT groups. Overall, they considered the waiting time between the initial interview and initiation of the program to be acceptable. The main obstacle to continuing mindfulness practice noted by all 14 participants was the lack of a follow-up program, and most of the participants expressed a desire to participate in a “maintenance” mindfulness-practice group. In MBCT, parts of the final sessions are focused on discussing the importance of continuing mindfulness practice after the end of the program to help participants develop an “action plan” for the future. As the results from the interviews reveal, some—but not all—of the participants managed to incorporate mindfulness practice into their everyday life. However, several participants reported finding it difficult to sustain this practice without group support. This finding is highly relevant for MBCT implementation in the primary care setting. Given the clinical characteristics of our sample—mostly individuals with adjustments disorders and mild-moderate affective symptoms—it could be argued that follow-up is less important than for individuals with major depressive disorder in which relapse is a common feature. However, the available evidence suggests that mindfulness training not only improves mental health conditions but also fosters wellbeing (Baer et al. 2012; Brown and Ryan 2003). The positive impact of mindfulness practice and its focus on providing practitioners with a greater awareness of the mind’s automatic patterns might be useful in many areas beyond symptom improvement.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, these findings are based on a heterogeneous clinical and socio-demographic sample, which may not be representative of other samples. Despite this heterogeneity, our data show that, overall—regardless of the specific diagnosis—the symptoms improved in all participants and the intervention was well accepted. Second, the measures used to assess symptoms could have been complemented with other measures. For example, it would have been valuable to obtain data on changes in the participants’ mindfulness skills, and to more closely assess the amount of at-home practice. As with all qualitative data, the findings are unique to the specific sample. In addition, the participants’ experiences were evaluated retrospectively; nevertheless, conducting the interviews 3 months after completion of the MBCT enabled us to obtain information about the participants’ post-MBCT experience with mindfulness practice. Unfortunately, individuals who discontinued MBCT were underrepresented in our sample, and therefore we do not have any information about how these individuals perceive MBCT. This limitation could be overcome in future studies by obtaining the opinions of participants who withdraw. Another limitation, related to the naturalistic study design, is that the sessions were not videotaped to assess adherence to the treatment protocol. Nevertheless, the teacher was supervised by trained-certified MBCT teachers to minimize deviations from the MBCT manual. Finally, the fact that the same therapist conducted all the groups could have also introduced some bias.

Future research should include a wider variety of outcome measures, to further investigate the impact of MBCT on transdiagnostic populations. Qualitative research should focus on those who discontinue the intervention in order to gain a better understanding of the barriers that prevent some individuals from fully engaging in MBIs and, more specifically, MBCT. Finally, cost-effective analyses are needed to better describe the impact of MBCT in primary care.

References

Allen, M., Bromley, A., Kuyken, W., & Sonnenberg, S. J. (2009). Participants’ experiences of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: it changed me in just about every way possible. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37(4), 413–430.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: Author.

Ansseau, M., Dierick, M., Buntinkx, F., Cnockaert, P., De Smedt, J., Van Den Haute, M., & Vander Mijnsbrugge, D. (2004). High prevalence of mental disorders in primary care. Journal of Affective Disorders, 78(1), 49–55.

Baer, R. A., Lykins, E. L. B., & Peters, J. R. (2012). Mindfulness and self-compassion as predictors of psychological wellbeing in long-term meditators and matched nonmeditators. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(3), 230–238.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Cormack, D., Jones, F. W., & Maltby, M. (2018). A “collective effort to make yourself feel better”: the group process in mindfulness-based interventions. Qualitative Health Research, 28(1), 3–15.

Crane, R. S., & Kuyken, W. (2012). The implementation of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: learning from the UK health service experience. Mindfulness, 4(3), 246–254.

Crane, R. S., Kuyken, W., Mark, J., Williams, G., Hastings, R. P., Cooper, L., & Fennell, M. J. V. (2012). Competence in teaching mindfulness-based courses: concepts, development and assessment. Mindfulness, 3(1), 76–84.

Demarzo, M. M. P., Cebolla, A., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2015a). The implementation of mindfulness in healthcare systems: a theoretical analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 37(2), 166–171.

Demarzo, M. M. P., Cuijpers, P., Zabaleta-del-olmo, E., Mahtani, K. R., Vellinga, A., & Vicens, C. (2015b). The efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in primary care: a meta-analytic review. The Annals of Family Medicine, 13(6), 573–582.

Dimidjian, S., & Segal, Z. V. (2015). Prospects for a clinical science of mindfulness-based intervention. American Psychologist, 70(7), 593–620.

Eatough, V., & Smith, J. (2006). I was like a wild wild person: understanding feelings of anger using interpretative phenomenological analysis. British Journal of Psychology, 97(4), 483–498.

Elices, M., Pascual, J. C., Portella, M. J., Feliu-Soler, A., Martín-Blanco, A., Carmona, C., & Soler, J. (2016). Impact of mindfulness training on borderline personality disorder: a randomized trial. Mindfulness, 7(3), 584–595.

Finucane, A., & Mercer, S. W. (2006). An exploratory mixed methods study of the acceptability and effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for patients with active depression and anxiety in primary care. BMC Psychiatry, 6(1), 14.

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60.

Hertenstein, E., Rose, N., Voderholzer, U., Heidenreich, T., Nissen, C., Thiel, N., et al. (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder – a qualitative study on patients’ experiences. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 185.

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12-19.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte.

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., et al. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771.

Kuyken, W., Byford, S., Taylor, R. S., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., et al. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 966–978.

Kuyken, W., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., Taylor, R. S., Byford, S., et al. (2010). How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(11), 1105–1112.

Kuyken, W., Hayes, R., Barrett, B., Byng, R., Dalgleish, T., Kessler, D., et al. (2015). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 386(9988), 63–73.

Kuyken, W., Warren, F. C., Taylor, R. S., Whalley, B., Crane, C., Bondolfi, G., et al. (2016). Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse an individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(6), 565–574.

Magán, I., Sanz, J., & García-Vera, M. P. (2008). Psychometric properties of a Spanish version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) in general population. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 11(2), 626–640.

Mason, O., & Hargreaves, I. (2001). A qualitative study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74(2), 197–212.

Parke, A., & Griffiths, M. (2012). Beyond illusion of control: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of gambling in the context of information technology. Addiction Research & Theory, 20(3), 250–260.

Piet, J., & Hougaard, E. (2011). The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1032–1040.

Roca, M., Gili, M., Garcia-Garcia, M., Salva, J., Vives, M., Garcia Campayo, J., & Comas, A. (2009). Prevalence and comorbidity of common mental disorders in primary care. Journal of Affective Disorders, 119(1–3), 52–58.

Rycroft-Malone, J., Gradinger, F., Griffiths, H. O., Crane, R., Gibson, A., Mercer, S., et al. (2017). Accessibility and implementation in the UK NHS services of an effective depression relapse prevention programme: learning from mindfulness-based cognitive therapy through a mixed-methods study. Health Services and Delivery Research, 5(14), 1–190.

Sanz, J., Perdigón, A. L., & Vázquez, C. (2003). The Spanish adaptation of Beck’s Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II): psychometric properties in the general population. Clínica y Salud, 14(3), 249–280.

Sanz, J., García-Vera, M. P. A. Z., Espinosa, R., Fortún, M., & Vázquez, C. (2005). Adaptación española del inventario para la depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): Propiedades psicométricas en pacientes con trastornos psicológicos. Clínica y Salud, 16(2), 141–142.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Segal, Z. V., Bieling, P., Young, T., MacQueen, G., Cooke, R., Martin, L., & Levitan, R. (2010). Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(12), 1256–1264.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Theory, method and research. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Sundquist, J., Sa Lilja, Å., Palmé, K., Memon, A. A., Wang, X., Johansson, L. M., & Sundquist, K. (2015). Mindfulness group therapy in primary care patients with depression, anxiety and stress and adjustment disorders: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(2), 128–135.

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M., Ridgeway, V. A., Soulsby, J. M., & Lau, M. A. (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 615–623.

van der Velden, A. M., Kuyken, W., Wattar, U., Crane, C., Pallesen, K. J., Dahlgaard, J., et al. (2015). A systematic review of mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 26–39.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Bradley Londres for his help in editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG: designed and executed the study. ME: executed the study and wrote the paper. MP: executed the study, collaborated with data analysis, and wrote part of the results. LMM: collaborated with the writing of the study. AJ: collaborated in the writing and data analyses. VP: collaborated with the writing of the final manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission. Miguel Gárriz and Matilde Elices contributed equally to this work

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital del Mar (Barcelona Spain).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gárriz, M., Elices, M., Peretó, M. et al. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Delivered in Primary Care: a Naturalistic, Mixed-Methods Study of Participant Characteristics and Experiences. Mindfulness 11, 291–302 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01166-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01166-y