Abstract

Mainstream mindfulness programs, as in first-generation mindfulness-based interventions, generally do not incorporate Buddhist ethics, causing some scholars to worry that they may encourage self-indulgence and have limited capacity to promote well-being. We compare the effects of practicing mindfulness with additional ethical instruction (EthicalM) or without such instruction (SecularM) on well-being and prosocial behavior. Participants (N = 621) completed 6 days of ethical or secular mindfulness exercises or active control exercises. Secular and ethical mindfulness both reduced stress (EthicalM: p = 0.011, d = − 0.25; SecularM: p = 0.005, d = − 0.28) and increased life satisfaction (EthicalM: p = 0.008, d = 0.26; SecularM: p = 0.069, d = 0.18) and self-awareness (EthicalM: p = 0.011, d = 0.25; SecularM: p = 0.051, d = 0.19). Ethical mindfulness also enhanced personal growth (p = 0.032, d = 0.21). Ethical, relative to secular, mindfulness also increased prosocial behavior—money donated to a charity (p = 0.020, d = 0.24). This effect was moderated by trait empathy: Trait empathy predicted donation amounts for participants who had completed mindfulness exercises (ethical or secular) but not controls. Furthermore, low trait empathy participants gave significantly less money following secular mindfulness practice than control exercises, whereas high trait empathy participants gave more money following ethical mindfulness practice than control exercises. Mindfulness training may thus have unintended consequences, making some people less charitable, though incorporating instruction on ethics, as in some second-generation mindfulness-based interventions, may forestall such effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mindfulness, originally a Buddhist spiritual practice, has been widely adopted in secular form to enhance psychological well-being (see Good et al. 2016). Since its debut as a component of structured clinical programs (e.g., Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction [MBSR], Kabat-Zinn 1990; Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy [MBCT], Segal et al. 2002), shorter and less intensive mindfulness meditation programs have been implemented in schools, corporations (e.g., Google; Tan 2012), and government agencies (e.g., the US Army; Myers 2015). With the rapid expansion of technology and the Internet, relatively brief mindfulness practices have also been popularized in online platforms and apps such as Headspace which is currently used in over 190 countries (Headspace 2017). It is therefore important to understand the effects of such mindfulness practices and, in particular, any consequences of divorcing mindfulness practices from instruction in the ethical principles of Buddhism.

Within psychology, mindfulness is commonly conceptualized as the awareness that arises from intentionally paying attention to present-moment experiences without judgment (Brown and Ryan 2003; Kabat-Zinn 1990).This “bare attention” conceptualization of mindfulness is ethically neutral (Bodhi 2011; Purser and Milillo 2015). In Buddhist practices, mindfulness is embedded in a moral framework intended to bring attention to the consequences of one’s actions, so as to encourage “wholesome” acts, which can alleviate suffering. “Unwholesome” acts, in contrast, can perpetuate suffering and ill-being and may be discerned by their consequences within the context of Buddhist ethical principles (see Harvey 2000). Secular mindfulness, as in most first-generation mindfulness-based interventions (FG-MBIs), generally lacks a comparable ethical framework to help individuals identify wholesome and unwholesome actions. This omission of explicit ethical principles from mindfulness practice has caused some scholars to worry that it may encourage self-indulgence and have limited capacity to promote well-being because it does not address the underlying thoughts and behaviors that may perpetuate ill-being (Greenberg and Mitra 2015; Monteiro et al. 2015). Because of these concerns, these Buddhist scholars and psychologists have considered the issue of whether ethics should be incorporated into mindfulness programs (e.g., Baer 2015; Purser 2015; Van Gordon et al. 2015a, b). They have called for tests of the effects of incorporating ethical principles into mindfulness-based programs, providing one impetus for some second-generation mindfulness-based interventions (SG-MBIs). Therefore, it is important to test the effects of mindfulness with and without ethical instruction on well-being and prosocial behavior.

A focus on prosocial behavior is important because the foundation of contemplative and meditative practices in Buddhism is the intention to cultivate virtue (Shapiro et al. 2012). Prosociality is also a core component of wholesome acts in Buddhism doctrine. As noted, some scholars worry that secular mindfulness practices may encourage self-indulgence (i.e., a disproportionate focus on oneself relative to others), which could undermine wholesome actions and prosocial behavior (Baer 2015; Purser 2015; Van Gordon et al. 2015a, b). A focus on prosocial behavior is also important because evidence for whether secular mindfulness increases empathy and prosocial behavior is mixed. Some research has found that mindfulness training increases prosocial behavior, making people more likely to give up their seat to a confederate struggling with crutches (Condon et al. 2013; Lim et al. 2015). This finding might not reflect increased compassion in mindfulness participants relative to controls, however. Rather, it may reflect a greater tendency among mindfulness participants to notice the individual or act decisively (as the prosocial act needed to occur within 2 min to be recorded). These studies were also limited by small sample sizes. A more recent, well-powered study observed no effect of a mindfulness induction on prosocial responding (i.e., behaving inclusively towards someone who had been socially excluded; Ridderinkhof et al. 2017). These studies vary in multiple ways that might contribute to their divergent results. Nevertheless, it is clear that more research testing the effects of secular mindfulness on prosocial behavior is needed.

In addition to providing a further test of the effects of secular mindfulness on prosocial behavior, we also test whether incorporating information about Buddhist ethical principles into secular mindfulness training enhances prosocial behavior. Some scholars argue that mindfulness training can increase prosocial behavior, but that explicit instructions that cultivate compassion or communicate ethical principles may be required for it to do so (Greenberg and Mitra 2015; Kristeller and Johnson 2005). Without such instruction to guide the awareness cultivated by mindfulness, these practices may enhance the influence of personality on behavior, in a manner similar to how self-consciousness enhances the effects of personality on behavior (Smith and Shaffer 1986). With respect to self-consciousness, Smith and Shaffer (1986) observed that participants higher in self-reported altruism were more likely to take an opportunity to help another person in need, but only when those participants were also high in private self-consciousness. Similarly, secular mindfulness may increase awareness and acceptance of personal values and encourage behaviors consistent with them (Brown and Ryan 2003). This effect may typically promote well-being but some values are relatively self-interested and focus on self-advancement (e.g., Paulhus and Trapnell 2008). Secular mindfulness may accordingly increase prosocial behavior for some people but decrease it for others, contributing to inconsistent findings in prior research. Indeed, a brief secular mindfulness induction in one study made narcissists less empathic (i.e., less accurate in reading others’ emotions; Ridderinkhof et al. 2017). It is therefore possible that mindfulness practice may cause trait empathy (an important aspect of prosocial personality; Davis 1983) to predict prosocial behavior to a greater extent.

Notably, most SG-MBIs that have been studied are, understandably, long-term interventions (typically 8 weeks) and/or taught face-to-face (e.g., Shonin et al. 2014; Singh et al. 2007, 2013, 2014, 2016a, b; Van Gordon et al. 2017). We designed and tested effects of a series of brief, online ethical mindfulness exercises on well-being, and prosocial behavior relative to secular mindfulness exercises and active control exercises. As mentioned earlier, many secular mindfulness practices now rely on relatively brief daily exercises that are often administered online through pre-recorded instruction (e.g., Headspace). It is therefore important to examine whether a focus on ethical principles may create benefits for practitioners even in this brief format. We tested effects of including ethical principles in mindfulness practices on negative dimensions of well-being such as stress and depressive symptoms, as well as positive dimensions such as life satisfaction, self-determination, and psychological well-being. We also tested effects of mindfulness training, with and without information about ethical principles, on prosocial behavior, by inviting participants to make a charitable donation from their own compensation money—a significant behavioral measure of prosociality that involves personal costs. We hypothesized that participants who practiced ethical mindfulness would demonstrate the greatest increases in psychological well-being and demonstrate the most prosocial behavior.

Method

Participants

A GPower analysis indicated that we needed 576 participants to achieve 80% power (to detect a small effect, f = 0.15). We over-sampled, recruiting as many undergraduates (N = 926) as possible before the end of an academic year, to allow for attrition. They participated for partial course credit. Of this initial sample, 129 participants failed to complete at least half of the mindfulness exercises and 160 participants failed to complete the post-test survey, leaving 637 participants. Because the post-test survey was administered online, we excluded 16 participants who failed attention checks, as recommended by Meade and Craig (2012). Analyses are thus reported on 621 participants (484 female, Mage = 18.64, SD = 1.88). Participants indicated their ethnic identifications as Caucasian (64.5%), Asian (21.9%), African (1.3%), or other (12.3%).

Procedure

Participants were recruited for an 8-day mindfulness study. They received instructions and completed pre-test measures during an in-lab session and were then randomly assigned to receive ethical mindfulness (EthicalM, n = 207), secular mindfulness (SecularM, n = 206), or analytic thought (Control, n = 208) exercises, once a day for the next 6 days. At 8 am each day, we emailed participants an audio-guided, 10-min mindfulness or control exercise and a survey, including manipulation checks and compliance checks, to be completed that day. Reminders were sent at 3 pm and 8 pm. The day after the final exercise, participants completed post-test measures online.

Measures

Mindfulness Exercises

All exercises, including control, were presented as mindfulness exercises to help control expectancies about effects of mindfulness. SecularM and Control exercises were adapted from Creswell et al. (2014). EthicalM closely paralleled SecularM, with the addition of information conveying the principles of no-harm and the interdependence of all beings. Both secular and ethical mindfulness practices focused on a core of mindfulness meditation, focusing on the breath, bodily sensations, and emotions, for example, without judgment. Within our ethical mindfulness exercises, we supplemented this practice with instruction on non-harm and interdependence. “Causing no harm” is one of the foundational ethical principles of Buddhism which can serve as a first step in building an ethical framework for secular mindfulness because it is widely accepted in other traditions (Greenberg and Mitra 2015) and parallels the moral foundation of care/harm within Moral Foundations Theory (Haidt and Graham 2007). We also included a related element of Buddhism, acknowledgment of the interdependence of all beings: the recognition that all beings are connected, which may encourage ethical action through appreciation that one’s actions impact others (Monteiro et al. 2015; Purser 2015). Accordingly, participants in the ethical mindfulness condition were encouraged to consider whether their qualities of mind reflect “primitive” qualities such as anger, fear or grief, or “more refined” qualities such as generosity, gratitude, or kindness. They were guided to consider how all living beings share their experiences (e.g., breathing, seeking happiness) and are, in this way, connected to them. They were guided to reflect on the sensations instilled in them by having loving and kind thoughts. In these ways, we sought to provide ethical principles that might direct the awareness cultivated in participants through the mindfulness exercises.

Instructions within each mindfulness exercise focused on the following: the first exercises for SecularM and EthicalM were identical, focusing on observing breath and accepting wandering thoughts. Participants in SecularM were then encouraged to notice subtle bodily sensations while breathing (day 2), acknowledge and accept the transient nature of bodily tensions (day 3), notice distracting emotions and thoughts (day 4), realize the temporary nature of emotions and thoughts (day 5), and then review all of these skills (day 6). These exercises are consistent with many self-help mindfulness programs. Participants in EthicalM received the same instructions and were additionally encouraged to recognize that all human beings breathe the same air (day 2), experience similar bodily sensations (day 3), have similar distracting emotions and thoughts (days 4 and 5), and then to reflect on their connection with all living beings and the importance of respecting and not harming them (day 6). Control exercises involved attending to poems and analyzing their structure (day 1), imagery (day 2), word choice (day 3), metaphors (day 4), deeper meaning (day 5), and finally reviewing all the analysis techniques (day 6). All exercises were 10 min long with the same female narrator. Sample instructions from each mindfulness exercise are listed in Table 1. Full instructions are available in the Supplemental Materials available online.

Manipulation Check

After each exercise, participants completed the Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS; Lau et al. 2006, αs of all scales are reported in Tables 1 and 2) to assess experiences of mindfulness during the exercise (e.g., “I experienced myself as separate from my changing thoughts and feelings,” from 1 [Not at all] to 7 [Very much]).

Dispositional Mindfulness

To assess trait mindfulness, participants completed the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown and Ryan 2003; e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present,” from 1 [Almost always] to 6 [Almost never]).

Dispositional Empathy

Participants completed the empathic concern (affective empathy; e.g., “I would describe myself as a pretty soft-hearted person”) and perspective taking (cognitive empathy; e.g., “When I’m upset at someone, I usually try to ‘put myself in his shoes’ for a while”) subscales of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis 1983; from 1 [Does not describe me well] to 5 [Describes me very well]). These subscales (r = 0.50, p < 0.001) were combined to index trait empathy. Trait empathy reflects characteristic ways of reacting to others’ experiences.

Well-Being

Participants completed the following questionnaires at both pre- and post-test to assess subjective well-being:

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), a 10-item scale measuring the amount of stress experienced during the prior week (Cohen et al. 1983). Participants rated items, such as “In the last week, how often have you felt nervous and stressed?” from 1 (Never] to 5 (Very often). Higher scores indicate the experience of greater stress.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996), a 21-item scale measuring participants’ depressive symptoms. For each item, participants indicate which of four statements, reflecting an escalating severity of depressive symptoms best describes them (e.g., “I do not feel sad,” “I feel sad,” “I am sad all the time and I can’t snap out of it,” “I am so sad and unhappy that I can’t stand it”). Higher scores indicate more intense depressive symptoms.

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS), a 5-item scale measuring satisfaction with one’s current life (Diener et al. 1985). Participants rated items, such as “I am satisfied with my life,” from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). Higher scores reflect greater life satisfaction.

Subjective Happiness Scale, a 4-item scale measuring how happy participants consider themselves to be (SHS; Lyubomirsky and Lepper 1999). Participants rated items on a 7-point scale, such as “In general, I consider myself,” from 1 (Not a very happy person) to 7 (A very happy person).

Self-Determination Scale (SDS), a 10-item measuring people’s sense of clarity about themselves (Self-Awareness) and sense of autonomy in their behavior (Perceived Choice; Sheldon et al. 1996). For each item, participants are presented with two statements, such as “A. I feel that I am rarely myself” and “B. I feel like I am always completely myself” and indicate their accuracy by choosing a number from 1 (Only A feels true) to 5 (Only B feels true). Higher scores reflect greater self-clarity or perceived autonomy in one’s behaviors.

Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWB; Ryff 1989), a 42-item scale measuring multiple aspects of participants’ psychological well-being that are not limited to hedonic happiness. These aspects include participants’ attitude towards themselves (Self-Acceptance; e.g., “I like most aspects of my personality”), the quality of their relationships (Positive Relations; e.g., “People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others”), perceived autonomy in life (Autonomy; e.g., “I have confidence in my opinions, even if they are contrary to the general consensus”), sense of control over the environment (Environmental Mastery; e.g., “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live”), sense of purpose in life (Purpose; e.g., “I have a sense of direction and purpose in life”), and sense of continued development as a person (Personal Growth; e.g., “For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth”). Participants indicate the extent of their agreement with these statements on a scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree).

Compassionate and Self-Image Goals

Participants also completed measures of their compassionate goals (7 items) and self-image goals (6 items) within friendships (Crocker and Canevello 2008). Compassionate goals reflect goals to be supportive or contribute to another’s well-being. Self-image goals reflect concern with maintaining a desired interpersonal impression. Participants indicate the extent to which they adopted particular goals within their friendships over the preceding week (e.g., compassionate goals: “be supportive of others,” “make a positive difference in someone else’s life”; self-image goals: “avoid showing weakness,” “get others to recognize or acknowledge your positive qualities”), on a scale from 1 (Not at All) to 5 (Extremely). Higher scores reflect the adoption of more compassionate or self-image goals in the domain of friendship.

Empathic Reactions

At the end of the post-test survey, participants read an article about “Gaby,” a mother struggling with homelessness with her 3-year-old son after her husband’s death in a car accident. They story describes Gaby’s poor living conditions, at one time living “in half of an unfinished basement,” or in a house with “a leaky roof, poor plumbing and terrible heating so the house is extremely cold in the winter.” The article reported that Habitat for Humanity, a non-profit organization, is trying to provide Gaby with adequate housing, but lacks sufficient resources to do so. The full story is available online in the Supplemental Materials. After reading the story about Gaby, participants rated how they felt while reading the article. They rated how much they experienced each of a series of affective adjectives reflecting empathy (i.e., sympathetic, soft-hearted, warm, compassionate, tender, and moved) and personal distress (i.e., alarmed, grieved, troubled, distressed, upset, disturbed, worried, and perturbed; Batson 1987) on a scale from 1 (Not at All) to 7 (Extremely). Participants also rated three items reflecting how much they took Gaby’s perspective while reading the story (e.g., “When reading about Gaby, I found myself taking her perspective”) on a scale from 1 (Not at All) to 7 (Extremely). We measured participants’ empathic reactions and perspective taking while reading the story as potential mechanisms for the effects of the mindfulness practices on prosocial behavior.

Prosocial Behavior

Participants were then given $15 Canadian for participating and were told that the department is taking up a collection for the Habitat for Humanity fund to help build Gaby a new house. They were asked whether they would donate any of the money to Habitat for Humanity. They typed the amount of their voluntary donation in a textbox, as a measure of prosocial behavior.

Data Analyses

Of our initial sample, 49 participants failed to complete half of the mindfulness exercises on their assigned day of practice and 80 participants failed compliance checks for half of the mindfulness exercises (e.g., “I did not do the mindfulness exercise. I just did other things, instead, while waiting for it to end”). Furthermore, 160 participants failed to complete the post-test survey. Because the post-test survey was administered online, we excluded 16 participants who failed attention checks (e.g., “please select ‘agree’ for this question”), as recommended by Meade and Craig (2012). Thus, a total of 305 participants either did not complete the study or were excluded from analyses, 34.8% from the ethical mindfulness condition, 28.2% from the secular mindfulness condition, and 37% from the control condition.

To ensure the internal validity of our sample, we first tested whether participants who finished the study differed from those who did not on all demographic and pre-test measures using simple t tests. To test the effects of mindfulness training on well-being and charitable giving we conducted a series of ANCOVAs comparing experimental groups on post-test measures, using corresponding pre-test measures (where available) and trait mindfulness (MAAS) as covariates (all analyses produce equivalent results, in terms of pattern and significance, if MAAS scores are not controlled). We finally tested whether trait empathy moderated donation amount. We regressed donation amount on trait empathy (IRI, centered), effect-coded condition (EthicalM = 1, 0; SecularM = 0, 1; Control = − 1, − 1), and their interaction, with MAAS as a covariate. Simple effects were conducted to decompose significant interactions following recommendations outlined by Aiken and West (1991).

Data Availability Statement

All data are available at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9dpjt/)

Results

Table S1 in the Supplemental Material available online presents zero-order correlations between all study variables. We observed differences only for the MAAS and perceived choice subscale of the SDS, with those finishing the study being higher in mindfulness, t (925) = 2.05, p = 0.041, and perceived choice, t (923) = 2.98, p = 0.003. We also compared the final sample across conditions and observed no significant differences (all ps > 0.121). In particular, neither trait empathy nor mindfulness varied by condition (see Table 2). Our sample may thus be somewhat higher in mindfulness and perceived choice than the general population, but attrition did not compromise the internal validity of the study.

We then tested whether the manipulation induced mindfulness: the exercises did affect experiences of mindfulness as reported on the TMS, F (2, 617) = 5.52, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.018 (see Table 2). Both mindfulness groups reported greater mindfulness than controls (EthicalM: t = 0.19, p = 0.003, 95% CI [0.07, 0.32], d = 0.30); SecularM: t = 1.8, p = 0.007, 95% CI [0.05, 0.30], d = 0.27). The two mindfulness groups did not differ from each other (p > 0.250). For well-being, there were significant effects for stress (PSS, F [2, 616] = 4.84, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.015), life satisfaction (SWLS, F [2, 616] = 3.75, p = 0.024, ηp2 = 0.012), self-awareness (SDS, F [2, 615] = 3.60, p = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.012), self-image goals, F [2, 615] = 4.73, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.015, and personal growth (PWB, F [2, 616] = 2.97, p = 0.052, ηp2 = 0.010; see Table 3). Compared to controls, both mindfulness groups reported less stress (EthicalM: t = 2.49, p = 0.011, 95% CI [− 0.22, − 0.03], d = − 0.25; SecularM: t = 2.91, p = 0.005, 95% CI [− 0.23, − 0.04], d = − 0.28), less concern with self-image (albeit marginally for EthicalM: t = 1.59, p = 0.099, 95% CI [− 0.20, 0.2], d = − 0.16; SecularM: t = 3.01, p = 0.002, 95% CI [− 0.28, − 0.06], d = − 0.30), greater life satisfaction (EthicalM: t = 2.65, p = 0.008, 95% CI [0.06, 0.37], d = 0.26; albeit marginally for SecularM: t = 1.89, p = 0.069, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.30], d = 0.18), and greater self-awareness (EthicalM: t = 2.51, p = 0.011, 95% CI [0.04, 0.29], d = 0.25; SecularM: t = 2.04, p = 0.051, 95% CI [0.00, 0.25], d = 0.19), but did not differ from each other (ps > 0.250). Finally, EthicalM participants reported significantly more personal growth than both controls (t = 2.12, p = 0.032, 95% CI [0.01, 0.23], d = 0.21) and SecularM participants (t = 2.12, p = 0.039, 95% CI [0.01, 0.23], d = 0.20). We did not observe any other significant differences between conditions for other well-being measures.

For prosociality, condition did not affect compassionate goals within friendships during the week of training (ps > 0.250). Neither did condition affect empathic concern, personal distress, nor perspective taking experienced while reading about Gaby (all ps > 0.250). For the measure of prosocial behavior, 27 participants did not proceed to the donation page after reading about Gaby, and thus did not indicate whether they would donate or not. They were accordingly excluded from the following analyses of donation decisions. Condition did affect donation amount, F (2, 590) = 2.71, p = 0.067, ηp2 = 0.009 (see Table 2). EthicalM participants donated more than SecularM participants (t = 0.1.32, p = 0.020, 95% CI [0.23, 2.71]), d = 0.24) but not Control participants (p = 0.221). SecularM participants did not differ from Control participants (p > 0.250). Nearly half of the participants donated nothing, however, which created a non-normal distribution for donation amounts. To check the robustness of our findings, we therefore transformed donations into a binary variable (0 = no donation, 1 = donation) and conducted a logistic regression analysis which produced consistent results. Specifically, EthicalM participants were significantly more likely to make a donation than SecularM participants (B = 0.437, Wald = 4.57, p = 0.032, Exp(B) = 0.64, R2Nagelkerke = 0.011) but not Control participants (p > 0.250). SecularM participants did not differ from Control participants (p = 0.124).

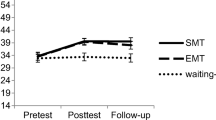

Finally, there was a significant interaction with trait empathy, Δ F (2, 586) = 3.57, p = 0.029, Δ R2 = 0.012 (see Fig. 1). Simple effect analyses reveal that, for participants with low trait empathy (− 1 SD), SecularM participants donated less than Control participants (β = − 0.13 t = − 1.99, p = 0.047) though there was no difference was between EthicalM and Control participants (p > 0.250). Among participants with high trait empathy (+1 SD), EthicalM participants donated more than Control participants (β = 0.19, t = 2.89, p = 0.004) though there was no difference between SecularM and Control participants (p > 0.250). Simple slope analyses show that participants with high trait empathy donated significantly more money than participants with low trait empathy in both mindfulness groups (EthicalM: β = 0.29, t = 4.31, p < 0.001; SecularM: β = 0.23, t = 3.26, p = 0.001), but not in the Control group (p > 0.250).

Discussion

Brief online mindfulness practices are widely accessible through popular books, websites, and meditation apps. Like FG-MBIs, these practices generally omit information about Buddhist ethical principles. Focusing on the effects of the secular mindfulness exercises in the present study—which are similar to the exercises presented in many popular mindfulness apps and platforms—our results partially support the efficacy of such secular mindfulness practices for enhancing well-being. Secular mindfulness training decreased stress and concerns with self-image, and increased life satisfaction (though marginally) and self-awareness relative to controls. Incorporating information about the ethical principles of non-harm and interdependence did not diminish these effects. In fact, ethical mindfulness training increased personal growth relative to control participants and those that completed secular mindfulness training.

Our results, however, may also support concerns that secular mindfulness practices can encourage self-indulgence. Mindfulness increased the relation between trait empathy and prosocial behavior. Trait empathy did not predict charitable giving for control participants—as general traits often fail to predict specific behaviors (Mischel 1968)—but did predict charitable giving for participants who completed mindfulness training (whether ethical or secular). Among low trait empathy participants, secular mindfulness training reduced charitable giving relative to controls; that is, low trait empathy participants who practiced secular mindfulness donated less money to charity than those who practiced no mindfulness at all. But ethical mindfulness training increased charitable giving overall, compared to secular mindfulness training. Among high trait empathy participants, ethical mindfulness training increased charitable giving relative to controls; that is, high trait empathy participants who practiced mindfulness with instruction on the principles of non-harm and interdependence donated more money to charity than controls.

These results may help explain the inconsistency in past findings for how mindfulness affects prosocial behavior. Secular mindfulness may primarily increase prosocial behavior for people who are already dispositionally likely to enact it (e.g., those high in trait empathy), but might actually decrease it for those who are not. Mindfulness training may also increase prosocial behavior to a greater extent when it explicitly includes information about ethical principles, as some extant programs do (Greenberg and Mitra 2015; Hutcherson et al. 2008). Some researchers argue that explicit instruction in ethical principles is not required for mindfulness training to encourage prosocial behavior, because such principles can be implicitly conveyed by teachers who embody ethical values (Baer 2015; Kabat-Zinn 2005). But this approach places considerable onus on individual teachers and is unlikely to be communicated well through online platforms or self-help books.

Our results may not generalize to all prosocial behavior, however. We examined monetary donations, but donations of time (e.g., volunteering), for example, may engage different psychological processes that reduce self-focus (Reed et al. 2016). Past research suggests that focusing on money can lead people to behave in less helpful and more selfish ways (e.g., DeVoe and Pfeffer 2007; Vohs et al. 2008). A focus on money may thus have limited the generosity of participants who are not generally disposed towards helping (i.e., those low in trait empathy), especially when mindfulness exercises did not incorporate ethical instruction. Low empathy individuals might be more generous with their time or in situations where money is not involved.

This possibility might help explain the discrepancy between our findings and past findings in which secular mindfulness inductions made participants more likely to give up their seat to a confederate struggling with crutches (Condon et al. 2013; Lim et al. 2015). Participants may have been generally more helpful in that situation because it did not focus on money. As mentioned earlier, however, this effect might also reflect a greater likelihood of noticing the person in need. Because participants in our study were explicitly directed to read about Gaby and directly asked to make a donation, our results are not likely to be due to differential noticing of the person in need. Whatever the reason for the discrepancy in the overall effect of secular mindfulness on prosocial behavior, our results suggest that an ethical focus may still enhance effects of secular mindfulness on helping.

Our results, moreover, leave some questions about how our ethical instructions enhanced prosocial behavior. We conceptualize our instructions on the ethical principles of non-harm and interdependence as providing internal guides for behavior, which direct the awareness cultivated by mindfulness practice. We acknowledge, however, that the effect of our instructions may more directly encourage compassion, as in some established compassion or kindness-based practices. Loving-kindness meditation, for example, encourages feelings of compassionate love towards the self and other beings (Salzberg 1995). A typical loving-kindness meditation encourages practitioners to first cultivate kindness towards oneself, and then towards close others, strangers, and all living beings. Our ethical mindfulness exercises, on the other hand, focus first on cultivating mindfulness, and then add instructions on the ethical principles of non-harm and interdependence. Practitioners are encouraged to see the connection of their experiences to those of other living beings, which provides the rationale for cultivating respect for those beings. Despite these differences, it is possible that a combination of mindfulness practices and loving-kindness meditation would have an effect similar to our ethical mindfulness exercises (e.g., Shapiro et al. 2012). This may be particularly the case because we focused specifically on the ethical principles of non-harm and interdependence. Although foundational, these principles are directly relevant to the cultivation of compassion.

Our approach is also similar, in some ways, to the cultivation of self-compassion (Neff and Germer 2013). A typical self-compassion exercise might involve focusing on a past negative life event, and encourage participants to identify, “as many ways as you can think of in which other people also experience similar events to the one you just described,” and to, “express understanding, kindness, and concern to yourself the way you might express concern to a friend who had undergone the experience.” It may also help participants to develop non-judgmental awareness of the described event through instructions such as “Describe your feelings about the experience in an objective and unemotional fashion” (Leary et al. 2007, p. 899). Self-compassion exercises are similar to our ethical mindfulness exercises in that they may both help participants to cultivate non-judgmental awareness and encourage a sense of connection to other people. The connection encouraged in self-compassion, however, focuses on a sense of common humanity, the recognition that other people experience the same challenges as oneself. Our ethical mindfulness instructions include some elements that may encourage a sense of common humanity, but do not primarily focus on cultivating awareness that others face similar challenges as oneself. Nevertheless, practicing mindfulness alongside exercises designed to cultivate self-compassion may produce effects similar to those observed here. The points of convergence and difference between ethically informed mindfulness practices, on the one hand, and loving-kindness and self-compassion practices, on the other, should be explored in future research.

Our findings also point to the potential scalability of mindfulness exercises for enhancing well-being and prosocial behavior; that is, that even relatively brief mindfulness-based exercises can produce some benefits for psychological well-being and prosociality. Some individuals may not have sufficient time or financial resources to regularly attend meditation classes with certified teachers or participant in more intensive mindfulness-based programs (Lim et al. 2015). It seems likely that pre-recorded mindfulness exercises, like those used in the current study, will remain widely popular. Our findings suggest that such exercises can benefit well-being, and may, with an added ethical focus, increase prosocial behavior. It is important to note, however, that online practices are likely not as effective as intensive, face-to-face mindfulness interventions. We did not, for example, observe significant effects of mindfulness training on depressive symptoms, subjective happiness, perceived choice, or a number of aspects of psychological well-being. It is possible that a more intensive intervention would benefit these aspects of well-being. Testing the effects of incorporating an ethical focus into longer-term interventions should be a priority for future research.

The lack of effect on depressive symptoms may, however, reflect low levels of depression in our sample. Pre-test scores on the BDI-II (M = 10.71, SD = 0.44) indicated minimal depression (0–13), making it unlikely that mindfulness training could improve depressive symptoms. Similarly, our final sample scored higher in perceived choice than the general population, making enhancement on this outcome potentially difficult. Our sample seems typical in terms of its subjective happiness and psychological well-being, however, and past research suggests the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions on these two outcomes (e.g., Bögels et al. 2008; Carmody et al. 2009). It may be the case that our 6-day online exercises were simply insufficient to improve these outcomes.

Similarly, we did not observe a significant effect of mindfulness training on compassionate goals. In contrast to a charitable donation, adopting more compassionate goals in friendships (e.g., to “avoid being selfish or self-centered” or “be supportive of others”) may require a more sustained effort, which might be better facilitated by a more intensive intervention. Shapiro et al. (2012), for example, observed a significant increase in moral reasoning at a 2-month follow-up of an 8-week MBSR program. Notably, their program specifically incorporated “a ‘loving-kindness’ meditation to encourage empathy and compassion for others and oneself” (p. 506), suggesting that supplementing more intensive secular mindfulness training with loving-kindness may, at least, encourage prosociality. Notably, however, mindfulness training (both secular and ethical) in the current study reduced self-image goals in friendships, though this effect might reflect the benefits of mindfulness training for well-being. Self-image goals (e.g., to “avoid being rejected by others,” or “avoid showing your weaknesses”) may reflect interpersonal anxieties, which, like perceived stress, can be reduced by mindfulness training.

We also did not find effects of mindfulness training on state empathic concern or perspective taking while reading Gaby’s story. This lack of an effect may reflect the emotionally charged nature of the story, but evidence that mindfulness training increases empathy is mixed. Some studies support the idea that mindfulness training enhances empathy (Birnie et al. 2010; Shapiro et al. 1998), whereas others do not (Beddoe and Murphy 2004; Galantino et al. 2005; Ridderinkhof et al. 2017). Nevertheless, our results suggest that mindfulness training with an ethical focus can enhance prosocial behavior without a mediating effect of empathic concern or perspective taking. Our results are generally consistent with the notion that mindfulness as “bare attention,” can increase the tendency for internal guides to direct behavior. These internal guides may reflect values associated with chronic dispositions (e.g., trait empathy) or associated with explicit instruction (e.g., a focus on no-harm and the interdependence of all beings). Determining the precise mechanism by which ethical mindfulness increases prosocial behavior, however, requires further research.

Despite some limitations, the current study demonstrates important differential effects of mindfulness practices with and without an ethical focus. We believe that our research provides preliminary evidence for the efficacy of SG-MBIs and brings attention to some limitations, and potential liabilities, of FG-MBIs. Notably, mindfulness potentiated effects of trait empathy on prosocial behavior, which led low empathy participants who practiced secular mindfulness to be less charitable. As noted, a brief secular mindfulness induction similarly reduced empathic responding among narcissists, individuals known to lack empathy (Ridderinkhof et al. 2017). It is worth considering whether secular mindfulness might have other unintended consequences by increasing the effects of personality on behavior. Our findings may accordingly have research implications, as secular mindfulness interventions might not be ideally suited to some individuals (e.g., those with Narcissistic Personality Disorder), or may need to be adapted to treat them, such as by incorporating an explicit ethical focus. Broadly, we hope that our findings will open further investigation of potential unintended effects of secular mindfulness and encourage greater focus on determining the right way to practice mindfulness for the right people and for the right purpose.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Baer, R. (2015). Ethics, values, virtues, and character strengths in mindfulness-based interventions: a psychological science perspective. Mindfulness, 6(4), 956–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0419-2.

Batson, C. D. (1987). Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic?. In advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 20, pp. 65-122). Cambridge: Academic press.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed.). San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Beddoe, A. E., & Murphy, S. O. (2004). Does mindfulness decrease stress and foster empathy among nursing students? Journal of Nursing Education, 43(7), 305–312.

Birnie, K., Speca, M., & Carlson, L. E. (2010). Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress and Health, 26(5), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1305.

Bodhi, B. (2011). What does mindfulness really mean? A canonical perspective. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2011.564813.

Bögels, S., Hoogstad, B., van Dun, L., de Schutter, S., & Restifo, K. (2008). Mindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parents. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(2), 193–209.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Carmody, J., Baer, R. A., LB Lykins, E., & Olendzki, N. (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 613–626.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 386–396 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2136404.

Condon, P., Desbordes, G., Miller, W. B., & DeSteno, D. (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2125–2127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613485603.

Creswell, J. D., Pacilio, L. E., Lindsay, E. K., & Brown, K. W. (2014). Brief mindfulness meditation training alters psychological and neuroendocrine responses to social evaluative stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 44, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.02.007.

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: the role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113.

DeVoe, S. E., & Pfeffer, J. (2007). When time is money: the effect of hourly payment on the evaluation of time. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 104(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.05.003.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Galantino, M. L., Baime, M., Maguire, M., Szapary, P. O., & Farrar, J. T. (2005). Association of psychological and physiological measures of stress in health-care professionals during an 8-week mindfulness meditation program: mindfulness in practice. Stress and Health, 21(4), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1062.

Good, D. J., Lyddy, C. J., Glomb, T. M., Bono, J. E., Brown, K. W., Duffy, M. K., Baer, R. A., Brewer, J. A., & Lazar, S. W. (2016). Contemplating mindfulness at work: an integrative review. Journal of Management, 42(1), 114–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315617003.

Greenberg, M., & Mitra, J. (2015). From mindfulness to right mindfulness: the intersection of awareness and ethics. Mindfulness, 6(1), 74–78.

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z.

Harvey, P. (2000). An introduction to Buddhist ethics: foundations, values and issues. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Headspace (2017). Retrived from: https://www.headspace.com/about-us. Accessed 24 Feb 2018.

Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion, 8(5), 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013237.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: the program of the stress reduction clinic at the University of Massachusetts medical center. New York: Delta.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Coming to our senses: healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. New York: Hyperion Books.

Kristeller, J. L., & Johnson, T. (2005). Cultivating loving kindness: a two-stage model of the effects of meditation on empathy, compassion, and altruism. Zygon: Journal of Religion & Science, 40, 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9744.2005.00671.x.

Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., et al. (2006). The Toronto mindfulness scale: development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(12), 1445–1467. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887.

Lim, D., Condon, P., & DeSteno, D. (2015). Mindfulness and compassion: an examination of mechanism and scalability. PLoS One, 10(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118221.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155 http://www.jstor.org/stable/27522363.

Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028085.

Mischel, W. (1968). Personality and assessment. New York: Wiley.

Monteiro, L. M., Musten, R., & Compson, J. (2015). Traditional and contemporary mindfulness: finding the middle path in the tangle of concerns. Mindfulness, 6(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0301-7.

Myers, N., Lewis, S., & Dutton, M. A. (2015). Open mind, open heart: An anthropological study of the therapeutics of meditation practice in the US. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 39(3), 487–504.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful selfcompassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44.

Paulhus, D. L., & Trapnell, P. D. (2008). Self-presentation of personality. Handbook of Personality Psychology, 19, 492–517.

Purser, R. (2015). Clearing the muddled path between traditional and contemporary mindfulness: a response to Monteiro, Musten and Compton. Mindfulness, 6(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0373-4.

Purser, R. E., & Milillo, J. (2015). Mindfulness revisited: a Buddhist-based conceptualization. Journal of Management Inquiry, 24, 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492614532315.

Reed, A., Kay, A., Finnel, S., Aquino, K., & Levy, E. (2016). I don't want the money, I just want your time: how moral identity overcomes the aversion to giving time to prosocial causes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(3), 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000058.

Ridderinkhof, A., de Bruin, E. I., Brummelman, E., & Bögels, S. M. (2017). Does mindfulness meditation increase empathy? An experiment. Self and Identity, 1(19), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1269667.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Salzberg, S. (1995). Loving-kindness: The revolutionary art of happiness. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

Segal, Z. V., Teasdale, J. D., Williams, J. M., & Gemar, M. C. (2002). The mindfulness-based cognitive therapy adherence scale: Inter-rater reliability, adherence to protocol and treatment distinctiveness. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 9(2), 131–138.

Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(6), 581–599.

Shapiro, S. L., Jazaieri, H., & Goldin, P. R. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction effects on moral reasoning and decision making. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(6), 504–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.723732.

Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., & Reis, H. T. (1996). What makes for a good day? Competence and autonomy in the day and in the person. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(12), 1270–1279. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672962212007.

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Meditation Awareness Training (MAT) for the treatment of co-occurring schizophrenia with pathological gambling: a case study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12, 181–196.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Singh, J., Curtis, W. J., Wahler, R. G., & McAleavey, K. M. (2007). Mindful parenting decreases aggression and increases social behavior in children with developmental disabilities. Behavior Modification, 31, 749–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507300924.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Karazia, B. T., Singh, A. D. A., Singh, A. N. A., & Singh, J. (2013). A mindfulness-based smoking cessation program for individuals with mild intellectual disability. Mindfulness, 4(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0148-8.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Karazsia, B. T., & Singh, J. (2014). Mindfulness-based positive behavior support (MBPBS) for mothers of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: effects on adolescents’ behavior and parental stress. Mindfulness, 5(6), 646–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0321-3.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Karazsia, B. T., & Myers, R. E. (2016a). Caregiver training in mindfulness-based positive behavior supports (MBPBS): effects on caregivers and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 98. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00098.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Karazsia, B. T., Chan, J., & Winton, A. S. W. (2016b). Effectiveness of caregiver training in mindfulness-based positive behavior support (MBPBS) vs. training-as-usual (TAU): a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1549. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01549.

Smith, J. D., & Shaffer, D. R. (1986). Self-consciousness, self-reported altruism, and helping behaviour. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 14(2), 215–220. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.1986.14.2.215.

Tan, C. M. (2012). Search inside yourself. New York City: Harper Collins Publishers.

Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., Griffiths, M. D., & Singh, N. N. (2015a). There is only one mindfulness: why science and Buddhism need to work together. Mindfulness, 6(1), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0379-y.

Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015b). Towards a second generation of mindfulness-based interventions. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49, 591591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415577437.

Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., Dunn, T., Garcia-Campayo, J., Demarzo, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Meditation Awareness Training for the treatment of workaholism: a non-randomised controlled trial. Journal of Behavioral Addiction, 6, 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.021.

Vohs, K. D., Mead, N. L., & Goode, M. R. (2008). Merely activating the concept of money changes personal and interpersonal behavior. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(3), 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00576.x.

Acknowledgements

We thank Victoria Parker, Leah Parent, Emma Smith, Amanda Montagliani, Hannah Rivard, and Sydney Goldberg for the help in collecting the data.

Funding

This research was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Grant (435-2014-1182) to C.H. Jordan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC collaboratively designed the study, executed the study, analyzed the data, wrote the first draft, and collaboratively revised further drafts of the paper. CHJ collaboratively designed the study, consulted on data analyses, and collaboratively revised drafts of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Board of Wilfrid Laurier University and the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOC 440 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Jordan, C.H. Incorporating Ethics Into Brief Mindfulness Practice: Effects on Well-Being and Prosocial Behavior. Mindfulness 11, 18–29 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0915-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0915-2