Abstract

Mindfulness refers to the ability of the individual to purposefully bring attention and awareness to the experiences of the present moment and relate to them in a non-reflexive, non-judgmental way. A growing body of evidence indicates that mindfulness can promote more satisfied romantic relationships and healthier relationship functioning; however, current models of how mindfulness contributes to romantic relationship processes focus almost exclusively on satisfaction as the primary outcome. Thus, whether mindfulness promotes greater relationship stability (i.e., likelihood for remaining intact vs. dissolving) remains unknown. The present study sought to address this issue by examining the longitudinal associations between romantic partners’ levels of trait mindfulness, relationship satisfaction, and relationship stability in a sample of 188 young adult unmarried different-sex dyads (n = 376 individuals). Utilizing a dyadic framework and multifaceted measure of mindfulness, multiple actor-partner interdependence models were used to examine the associations between male and female partners’ levels of overall mindfulness and facets of mindfulness, relationship satisfaction at 30 days post-baseline, and relationship dissolution status (intact vs. dissolved) at 90 days post-baseline. Results indicated that only female partners’ levels of overall mindfulness, observing of experience, acting with awareness, and nonreactivity to inner experience were associated with greater relationship stability (i.e., lower likelihood for relationship dissolution), though neither mindfulness nor any facet was associated with female partners’ relationship satisfaction. In contrast, male partners’ levels of describing with words and acting with awareness were associated with their own post-baseline satisfaction, but not with greater relationship stability. Female partners’ nonreactivity to inner experience was the only facet associated with the satisfaction of their partner. Results should be considered preliminary until additional studies can replicate these findings given high participant attrition rates at study follow-up time points. Findings from the present study contribute potentially novel insights into the role of mindfulness in the longitudinal satisfaction and stability of romantic relationships and increased clarity about which aspects of mindfulness might be most important for promoting relationship stability in young adult dating relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most individuals in the USA first enter into committed romantic relationships during young adulthood (i.e., between 18 and 25 years of age; Arnett and Tanner 2006; Regnerus and Uecker 2010). During this time, most young adults begin the process of forming an individual identity, separating from their family of origin, and exploring future career goals (Arnett and Tanner 2006). Simultaneously, most young adults also begin to develop standards for intimate relationships and gain experience with romantic partners before entering into more permanent romantic unions such as marriage (see Fincham and Cui 2010). Previous research has shown that the formation and maintenance of stable, satisfied romantic relationships during young adulthood is strongly associated with better mental and physical health (Braithwaite et al. 2010; Whitton et al. 2013) and later relationship success (Raley et al. 2007), making it an important developmental goal for individuals at this life stage (Collins and van Dulmen 2006).

Because young adulthood is a time during which individuals are beginning to enter into committed intimate relationships while simultaneously developing self-identity individuals at this life stage may be particularly receptive to efforts aimed at promoting favorable relationship behaviors and building relational skills. Such efforts have already been received favorably by young adult college students (Olmstead et al. 2011) and demonstrate promise in building young adults’ relationship knowledge and communication skills while reducing risky sexual behaviors (see Ponzetti 2015). Moreover, as young adults are likely to be engaging in and thinking about mate selection (Sassler 2010), cultivating an ability to notice, attend to, and effectively navigate less healthy relationship processes as they occur is likely to aid young adults in making decisions about who to choose as an appropriate partner, terminating less healthy romantic relationships before entering into more permanent unions such as marriage, and curbing later distress in relationships that do become more committed or permanent.

In general, previous research has linked mindfulness with a number of favorable individual-level psychological (Keng et al. 2011) and physical (Grossman et al. 2004) health outcomes, supporting efforts to incorporate mindfulness techniques into a variety of interventions, education programs, and therapies (Cullen 2011). Previous research also indicates that five distinct but related underlying sub-components that comprise the overall construct of mindfulness: observing of experience, describing with words, acting with awareness, nonjudging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience (Baer et al. 2006). Research utilizing the five-factor model of mindfulness has demonstrated differential associations between individual facets and a variety of outcomes, such as psychological well-being (Brown et al. 2015), depressive and anxious symptomology (Desrosiers et al. 2013), substance use (Levin et al. 2014), and dating violence (Brem et al. 2016). Thus, researchers have become increasingly interested in how specific cognitive, behavioral, and affective aspects of mindfulness (as well as the general tendency to be mindful) might contribute to favorable mental and physical health outcomes (Leary and Tate 2007).

Despite evidence of the salutary effects of mindfulness on the psychological and physical health of individuals, research on the interpersonal effects of mindfulness is still in its infancy. However, as the ability to lovingly and caringly connect with and cultivate compassion for other living beings is a core tenant of Buddhist spiritual and meditative practices, some scholars have posited that “it is congruent with Buddhist principles that mindfulness be taught within the context of relationships” (Gambrel and Keeling 2010, p. 416; Gehart 2012) and that mindfulness might play an important role in the health and functioning of romantic relationships in particular (see Atkinson 2013; Karremans et al. 2015 for review). For example, more mindful individuals might be more able or willing to take an interest and attend to their partner’s thoughts, emotions, and welfare while also being less reactive to stressful events that arise in their relationship (Kabat-Zinn 1993). Additionally, because mindful individuals are likely to be more intentional and less reflexive in their behaviors, more mindful partners might be better able to engage in interaction styles that promote healthy relationship functioning and effectively cope with negative emotional states in the context of their relationships. Thus, by being attentive to present experiences and engaging with them in a non-evaluative, non-reactive way, more mindful individuals might have a greater number of positive experiences in their romantic relationships while simultaneously minimizing corrosive relational processes that might lead to later deterioration.

In line with these theoretical assertions, previous research has consistently linked higher levels of trait mindfulness with increased relationship satisfaction (see Atkinson 2013; Karremans et al. 2015; Kozlowski 2013 for reviews), and with more skillful responses to relationship stress, increased empathy, greater acceptance of one’s partner, greater differentiation, increased sexual satisfaction, more secure spousal attachment, and better adjustment to relationship traumas (Barnes et al. 2007; Burpee and Langer 2005; Johns et al. 2015; Jones et al. 2011; Khaddouma et al. 2015a, b, 2016; Kimmes et al. 2017; Lenger et al. 2016; Wachs and Cordova 2007). Qualitative studies have documented generally positive experiences when partners jointly learn mindfulness or experience their partner learning mindfulness (e.g., Gillespie et al. 2015; Pruitt and McCollum 2010; Smith et al. 2015). Taken together, these findings support the notion that mindfulness is linked with better relationship quality and functioning in adult married (e.g., Burpee and Langer 2005; Wachs and Cordova 2007) and young adult unmarried (e.g., Barnes et al. 2007) romantic relationships.

Though current theory-driven models of how mindfulness confers relational benefits focus on relationship satisfaction or quality as the primary outcome (see Karremans et al. 2015), it is possible that more mindful partners might also experience greater relationship longevity—an important outcome to examine empirically, given the significant effects of romantic relationship dissolution on the mental and physical health of young adults (Rhoades et al. 2011; Sbarra and Emery 2005) and adults (Amato 2000; Lorenz et al. 2006). In fact, the current body of evidence linking mindfulness and relationship quality has provided an impetus for scholars to reasonably assert, “there seems to be a consensus that mindfulness can promote relationship satisfaction and longevity” (Karremans et al. 2015, p. 29). However, at present, empirical studies of the interpersonal effects of mindfulness have focused exclusively on aspects of relationship functioning and quality, and no previous studies have examined whether the positive association between mindfulness on relationship satisfaction actually translates to increased relationship longevity, though this would be expected since more satisfied relationships are often more stable (i.e., less prone to dissolution or thoughts and behaviors about dissolution; Booth et al. 1985; Yeh et al. 2006). Such data are crucial for informing current models of how mindfulness shapes romantic relationship processes and outcomes (e.g., Atkinson 2013; Karremans et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2015).

Moreover, since specific facets of mindfulness differentially contribute to individual-level psychological outcomes (Brown et al. 2015), variation in levels of facets of mindfulness may likewise differentially contribute to relationship outcomes. The few previous studies to examine the differential effects of levels of mindfulness facets on relationship outcomes support this notion. In one study, only the observing of experience and nonjudging of inner experience facets were positively associated with sexual and relationship satisfaction in a cross-sectional sample of dating young adults (Khaddouma et al. 2015a). Similarly, in a sample of long-term married couples, only the nonjudging of inner experience facet was significantly associated with individual spouses’ relationship satisfaction (Lenger et al. 2016). Finally, in the only longitudinal study to examine the effects of mindfulness facets on relationship satisfaction, increases in levels of acting with awareness and nonreactivity to inner experience were uniquely associated with increases in relationship satisfaction among individuals who participated in a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn 1990) course (Khaddouma et al. 2016). Given such limited and mixed findings regarding the differential role of mindfulness facets in promoting greater relationship satisfaction in both dating and more long-term relationships, more research is needed to elucidate precisely which facets might play a more influential role in the quality and subsequent stability that couples experience over time.

Finally, because the characteristics and behaviors of one partner are often related to both his or her own outcomes (i.e., actor effects) and his or her partner’s outcomes (i.e., partner effects; Cook and Kenny 2005; Kenny et al. 2006), it is important to utilize a dyadic framework for examining how levels of mindfulness contribute to individuals’ own and their partners’ relationship outcomes over time. At present, research examining the inter-partner effects of trait mindfulness on relationship functioning is severely lacking, and results from previous studies provide mixed findings regarding how one partner’s level of mindfulness contributes to the relationship experiences of the other partner. For example, Barnes et al. (2007) found that higher levels of trait mindfulness were associated with less severe emotional stress responses to relationship conflict, increased love and commitment, and more constructive communication behaviors among young adult dating partners, though these associations were found only in the context of actor effects, that is, mindfulness had beneficial effects only on the person’s own experience and not on the experience of the other member of the couple. However, when utilizing a multifaceted measure of mindfulness, studies have demonstrated more nuanced associations between specific aspects of mindfulness and inter-partner relationship outcomes. For example, in a cross-sectional sample of adult long-term married couples, only the nonjudging of inner experience facet was significantly associated with individuals’ own relationship satisfaction, whereas nonreactivity to inner experience was uniquely associated with the relationship satisfaction of their partners, even in the absence of a link with their own (Lenger et al. 2016). In another study, only the development of higher levels of acting with awareness was associated with increases in self-reported relationship satisfaction among individuals enrolled in a MBSR course; however, increases in both acting with awareness and nonreactivity to inner experience among these MBSR participants were associated with increased relationship satisfaction among their romantic partners (Khaddouma et al. 2016).

Taken together, previous research might suggest that more behaviorally oriented aspects of mindfulness, such as attending to activities of the moment with purposeful attention (acting with awareness) or inhibiting one’s immediate behavioral reactions to cognitive and emotional stimuli (nonreactivity to inner experience), may have particularly beneficial effects on the relationship satisfaction of one’s partner. Conversely, improvements in more cognitive or intrapersonal aspects of mindfulness, such as the tendency to notice or attend to internal and external experiences (observing of experience), assign labels to such experiences (describing with words), and take a non-evaluative stance toward sensations, cognitions, and emotions (nonjudging of inner experience) might be less visible to one’s partner, but might still play a role in one’s own ability to feel satisfied in the relationship.

Thus, the mixed findings from the few previous studies to examine the inter-partner relational effects of mindfulness indicate that whereas higher levels of mindfulness entail relational benefits to individual partners (i.e., actor effects), the effects of individuals’ mindfulness on their partners’ outcomes (i.e., partner effects) are still largely unknown and likely to vary by facet. Furthermore, as current theory-driven models of how mindfulness influences relationship outcomes posit that individual’s levels of mindfulness are likely to contribute to the relationship experiences of both partners (Karremans et al. 2015); utilizing dyadic frameworks to understand the role of mindfulness in longitudinal relationship stability is a crucial next step for research on this topic.

In sum, guided by previous research and theory, the present study sought to build upon previous studies linking higher levels of mindfulness with greater relationship satisfaction by examining the association between trait mindfulness and longitudinal dating relationship stability in a sample of young adults. In line with current models of how mindfulness influences relationship functioning (see Karremans et al. 2015), we utilize a dyadic framework to examine whether higher trait mindfulness is associated with longitudinal relationship satisfaction and subsequent stability (i.e., intact vs. dissolved at follow-up) in a sample of unmarried different-sex young adult couples. Moreover, we sought to address gaps in previous research by applying the five-factor model of mindfulness (Baer et al. 2006) to the relational outcomes of satisfaction and stability and examining differences in the associations with each facet. Based on previous research and theory, we hypothesized that romantic partners’ levels of mindfulness would be positively associated with their own (i.e., actor effects) and their partner’s (i.e., partner effects) relationship satisfaction 1 month post-baseline, which would then be positively associated with their shared subsequent relationship stability (i.e., intact vs. dissolved) 3 months post-baseline. At the level of individual facets of mindfulness, we hypothesized that more behaviorally oriented aspects of mindfulness (i.e., acting with awareness, nonreactivity to inner experience) would demonstrate the most robust inter-partner associations (i.e., partner effects). Remaining analyses were considered exploratory given the mixed results from previous studies concerning associations between facets of mindfulness and aspects of relationship functioning.

Method

Participants

Participants were students or the young adult romantic partners of students at a large southeastern university in the USA. Data were collected from both partners of 188 monogamous, unmarried different-sex young adult couples (n = 376 individuals) who consented to participate in a longitudinal online survey study of dating relationships. Of this sample, 354 individuals consented to the study and provided baseline data, and an additional 22 individuals (19 males, 3 females) provided data at follow-up time points, but not baseline data. Overall, approximately 53.7% of participants (n = 190 individuals) who completed baseline measures provided data at 30 days post-baseline, and 52.5% (n = 186 individuals) of participants provided data at 90 days post-baseline. Demographic and relationship characteristics of participants in the present study are displayed in Table 1.

Several demographic and relationship characteristics were associated with participation at follow-up. Gender was associated with participation at all follow-up time points such that females were more likely to complete surveys than males at 30 days (χ2 (1, 376) = 85.79, p < .001) and 90 days (χ2 (1, 376) = 21.78, p < .001) post-baseline. Race was associated with participation at 30-day follow-up only, such that White participants were more likely to complete surveys than non-White participants at 30 days post-baseline (χ2 (1, 376) = 4.12, p < .05). Additionally, baseline relationship satisfaction was significantly associated with participation at the 30-day post-baseline time point such that individuals who completed surveys reported higher baseline satisfaction than those who did not (F(1, 353) = 4.45, p < .05). No other demographic or relationship characteristics were associated with the likelihood of providing data at post-baseline time points.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the university where the study was conducted. Opportunities to participate in the study were advertised to students at a large southeastern university through paper flyers, an online research participation portal, and through announcements about the study in introductory psychology courses. Students signed up to participate in a survey study of dating relationships through an online survey system. After consenting to the study, participants were asked to provide the name and email address of their current romantic partners, who were then contacted by research staff via email within 24 h with an offer to participate in the study. Participants were eligible for the study if on a screener survey they reported being (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) involved in a monogamous, unmarried, and romantic relationship; and (3) willing to provide the name and email address of their current romantic partner. The importance of completing the questionnaires independently of their partner was stressed to all participants, and both partners were assured that they would not be able to access each other’s responses once submitted.

Participants who provided consent and completed baseline surveys were then emailed a link to complete an online follow-up survey at 30 and 90 days following their completion of the baseline survey. Participants were sent email reminders to complete the follow-up survey every 24 until 72 h after their initial contact about the follow-up survey. In an effort to maximize the amount of data available at each time point while also providing the fewest possible barriers to a participant’s decision to complete follow-up surveys, individuals who had a partner participating in the study but themselves neither consented nor declined to participate in the study on the baseline screener survey were re-contacted via email with an offer to participate in the study on the date of their respective partner’s follow-up time points of the study. Thus, some partners were able to provide data about their relationship functioning at later time points without having completed baseline measures. Participants elected to receive either a small cash award or course credit for an introductory psychology class in which they were currently enrolled as compensation for their participation in the study.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported their gender, age, race, sexual orientation, and academic level. Participants also reported whether they lived with, had children with, or were engaged to their current partner, as well as their relationship length (in months) with their current partner.

Mindfulness

The Five-Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al. 2006) is a 39-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess trait mindfulness. The FFMQ includes five subscales, consisting of observing of experience (e.g., “When I’m walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving), describing with words (e.g., “I can usually describe how I feel at the moment in considerable detail”), acting with awareness (e.g., “I do jobs or tasks automatically without being aware of what I’m doing”), nonjudging of inner experience (e.g., “I make judgments about whether my thoughts are good or bad”), and nonreactivity to inner experience (e.g., “I watch my feelings without getting lost in them”). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). Nineteen items are reversed, and all items on each subscale are summed to obtain individual subscale scores and summed across subscales to yield an overall mindfulness score. Higher scores on each subscale indicate higher levels of each facet of trait mindfulness and higher total scores indicate higher levels of overall mindfulness. The FFMQ has demonstrated good internal consistency in previous studies (Cronbach’s α ranging from .79 to .93; Caldwell et al. 2010), as well as good construct and cross-cultural validity across several studies (Christopher et al. 2012; de Bruin et al. 2012; Deng et al. 2011; Heeren et al. 2011).

Means, standard deviations, and possible range for the FFMQ in the current sample are displayed in Table 2. Internal reliability in the current sample was adequate across all subscales (total mindfulness = .78, observing of experience = .78, describing with words = .86, acting with awareness = .89, nonjudging of inner experience = .89, nonreactivity to inner experience = .77) with mean scores comparable to similar non-clinical young adult samples on total mindfulness (e.g., corresponding mean of 116.09; Khaddouma et al. 2015b) and each facet of mindfulness (e.g., 27.22 for observing of experience; 25.52 for describing with words; 25.84 for acting with awareness; 26.94 for nonjudging of inner experience; 21.70 for nonreactivity to inner experience; Roberts and Danoff-Burg 2010).

Relationship Satisfaction

The Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4; Funk and Rogge 2007) is a four-item self-report questionnaire that assesses relationship satisfaction. An example item includes “Please indicate the degree of happiness, all things considered, of your relationship” which is rated on a scale from 1 (extremely unhappy) to 6 (perfect). Items are summed to yield an overall assessment of relationship satisfaction with higher scores indicating greater relationship satisfaction. The CSI has shown high measurement precision and strong convergent validity with longer measures of relationship satisfaction in previous samples (Funk and Rogge 2007). The CSI has also demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α equal to.98) and strong promise as a superior measure of relationship satisfaction beyond previous measures, as it is currently the only relationship assessment scale developed using item response theory and is worded to be appropriate for non-married couples (Graham et al. 2011).

Means, standard deviations, and possible range for the CSI-4 in the current sample are displayed in Table 2. Internal reliability in the current sample was adequate at both time points of measurement (baseline = .72, 30 days post-baseline = .74) with mean scores comparable to similar non-clinical young adult samples on relationship satisfaction (e.g., corresponding mean of 16.00; Funk and Rogge 2007). Average levels of relationship satisfaction in the current sample were in the non-distressed range at baseline (M = 16.64 SD = 3.72), with 10.4% (n = 39) of the sample falling below the clinical cutoff score for relationship distress (13.5 on the CSI-4; Funk and Rogge 2007).

Relationship Stability

Relationship stability was assessed by asking participants if they were still involved in the relationship reported in the first wave of the study. Responses were coded as 0 = no (i.e., dissolved) and 1 = yes (i.e., intact). This item has previously been used to assess relationship dissolution in unmarried romantic relationships (Cui et al. 2011). Approximately 17.6% of couples who participated in the study (n = 33 dyads) reported that their relationship had dissolved at 90 days post-baseline.

Data Analyses

First, a series of preliminary analyses were conducted to assess the appropriateness of the data for meeting statistical assumptions. Data were assessed for skew and kurtosis, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test the normality of the distribution for each study variable. A series of ANOVA and chi-square statistical tests were then used to determine whether any demographic factors were associated with variables of interest in the current study, thus necessitating their inclusion as control variables in primary analyses. Additionally, due to the centrality of partners’ gender to study analyses, a series of paired samples t tests and chi-square statistical tests were used to evaluate whether male and female partners significantly differed on any variable of interest at baseline. Finally, bivariate correlations were calculated for male and female partners to test for significant associations among study variables.

To test study hypotheses, multiple longitudinal actor-partner interdependence statistical models (Cook and Kenny 2005; Kenny et al. 2006) were constructed and evaluated using MPlus version 7.11 (Muthén and Muthén 2013). Actor-partner interdependence models (APIMs) allow for statistical analysis of stability and reciprocity in dyadic relationships while accounting for shared variance and potential error co-variance in partners’ scores and are appropriate for short-term longitudinal data (Cook and Kenny 2005). Thus, path models were constructed using the dyad as the unit of analysis while specifying correlations between partner scores at each time point within each model. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML), which has been shown to provide more efficient and less biased estimates than alternative strategies such as pairwise or listwise deletion (Enders 2010; Kline 2011). Following procedures outlined by Schermelleh-Engel et al. (2003), model fit was assessed using the chi-square test of model fit (a non-significant chi-square value indicates that the model has acceptable fit), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) with the following cutoff values: CFI ≥ .95, TLI ≥ .95, RMSEA < .06. Path analyses were then used to examine the statistical significance of associations among variables within each APIM path model.

Results

Distribution analyses indicated that the acting with awareness, nonjudging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience facets of mindfulness as well as baseline and 30-day post-baseline relationship satisfaction deviated from a normal distribution, as indicated by significant Shapiro-Wilk indices. Results are displayed in Table 2.

No demographic characteristics of participants or their relationships were associated with relationship satisfaction at 30 days post-baseline, or with relationship dissolution status at 90 days post-baseline. However, analyses indicated that males and females significantly differed on several variables at baseline. Demographically, females were more likely to report being college freshmen (χ2 (6, 376) = 29.84, p < .001) than males and were, on average, approximately 1 year younger than males (t(166) = 4.09, p < .001). At baseline, females also reported lower levels than males on total mindfulness (M = 119.04 SD = 12.75 vs. M = 113.12 SD = 13.93, t(166) = 3.26, p < .001), describing (M = 26.88 SD = 5.59 vs. M = 25.34 SD = 6.15, t(166) = 2.06, p < .05), and nonreactivity to inner experience (M = 18.97 SD = 4.56 vs. M = 17.00 SD = 4.62, t(166) = 3.31, p < .001). No other significant baseline differences were observed between males and females.

Bivariate correlational analyses indicated that overall mindfulness was significantly positively associated with baseline relationship satisfaction for males (r = .23, p < .05), but not females. At the level of individual facets, describing (r = .10, p < .05), acting with awareness (r = .13, p < .05), and nonjudging of inner experience (r = .10, p < .05) facets of mindfulness were significantly positively correlated with baseline relationship satisfaction for females, whereas the observing of experience (r = .19, p < .01), describing (r = .22, p < .01), and nonreactivity to inner experience (r = .22, p < .01) facets of mindfulness were significantly positively correlated with baseline relationship satisfaction for males. The acting with awareness (r = .15, p < .05) was again positively correlated with relationship satisfaction at 30 days post-baseline for females. Finally, baseline relationship satisfaction was significantly positively associated with 30-day post-baseline satisfaction for both males (r = .43, p < .01) and females (r = .52, p < .01). Results are displayed in Table 2.

Given the results of preliminary analyses, path models in primary analyses were evaluated using maximum likelihood with robust standard error (MLR) estimation in order to account for the non-normal distribution of several variables of interest. MLR produces parameter estimates and standard errors that are robust to non-normality and calculates fit indices based on an estimate of multivariate kurtosis, thus taking into account and adjusting for non-normally distributed data (Curran et al. 1996). Additionally, the race was included as a control variable in paths to relationship satisfaction in all models given significant associations with the likelihood of survey completion at 30 days post-baseline. Lastly, baseline relationship satisfaction was also included as a control variable in paths to 30-day post-baseline relationship satisfaction in all models to account for varying levels of initial relationship satisfaction.

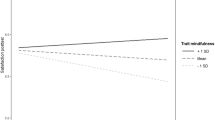

To examine the longitudinal inter-partner effects of mindfulness on relationship satisfaction and stability, we constructed actor-partner interdependence models (Cook and Kenny 2005) in which male and female partners’ respective baseline mindfulness predicted their own and their partners’ relationship satisfaction at 30 days post-baseline, which then predicted their joint relationship dissolution status at 90 days post-baseline. In order to examine the inter-partner effects of total mindfulness and each facet of mindfulness, six separate models were constructed with male and female partners’ respective total mindfulness and each facet of mindfulness scores included as independent predictor variables. Results are displayed in Fig. 1.

Actor-partner models of the effects of mindfulness and facets of mindfulness on relationship satisfaction and dissolution. Note: Relationship satisfaction represents satisfaction at 30 days post-baseline. Relationship dissolution represents dissolution status (0 = intact, 1 = dissolved) at 90 days post-baseline. Control variables to relationship satisfaction (e.g., baseline relationship satisfaction and race) were included in analyses, but are not shown in the diagram. Standardized estimates are shown. CFI = comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index, RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation. *p < .05, **p < .01 ***p < .001

Model fit indices indicated that each path model fits the data well (model fit statistics are displayed in Fig. 1). For all models, male partners’ relationship satisfaction at 30 days post-baseline was not associated with relationship dissolution at follow-up; however, significant negative associations between female partners’ relationship satisfaction and relationship dissolution were observed in all models. For total mindfulness, female (but not male) partners’ levels of mindfulness were significantly negatively associated with relationship dissolution (β = − .40, SE = .15, p = .01) but not with their own nor their partners’ relationship satisfaction (Fig. 1a). For observing ef Experience, female (but not male) partners’ levels of observing of experience were significantly negatively associated with relationship dissolution (β = − .47, SE = .15, p = .00) but not with their own nor their partners’ relationship satisfaction (Fig. 1b). For describing with words, neither female nor male partners’ levels of describing were significantly associated with relationship dissolution. However, male (but not female) partners’ levels of describing with words were significantly positively associated with their own relationship satisfaction (β = .18, SE = .08, p = .03; Fig. 1c). For acting with awareness, female (but not male) partners’ levels of acting with awareness were significantly negatively associated with relationship dissolution (β = − .29, SE = .12, p = .02) but not with their own nor their partners’ relationship satisfaction. However, male partners’ levels of acting with awareness were significantly positively associated with their own relationship satisfaction (β = .16, SE = .08, p = .03; Fig. 1d). For nonjudging of inner experience, neither female nor male partners’ levels of nonjudging of inner experience were significantly associated with relationship dissolution, nor were there significant intra- or inter-partner associations between nonjudging of inner experience and relationship satisfaction for either partner (Fig. 1e). For nonreactivity to inner experience, female (but not male) partners’ levels of nonreactivity to inner experience were significantly negatively associated with relationship dissolution (β = − .47, SE = .12, p = .00) and with their partners’ (but not their own) relationship satisfaction (β = .24, SE = .11, p = .03; Fig. 1f).

Discussion

Previous research indicates that mindfulness is associated with more satisfied romantic relationships and healthier relationship functioning (e.g., Atkinson 2013; Karremans et al. 2015; Kozlowski 2013); however, the association between mindfulness and the longitudinal stability (i.e., likelihood for remaining intact vs. dissolving over time) of relationships has remained unexplored. Thus, the present study examined the associations between young adult male and female dating partners’ levels of mindfulness and longitudinal relationship stability. Based on previous research and theory, it was hypothesized that partners’ levels of mindfulness would be positively associated with their own (i.e., actor effects) and their partner’s (i.e., partner effects) relationship satisfaction and subsequent stability and that more behaviorally oriented aspects of mindfulness would demonstrate the most robust partner effects at the level of individual facets of mindfulness. The results provided partial support for these hypotheses and potentially novel insights into the role of mindfulness in the longitudinal relationship stability of young adult dating partners.

First, the results suggest that gender might play an important role in the associations between mindfulness, relationship satisfaction, and dating relationship stability over time. Specifically, young adult female partners’(but not young adult male partners’) general tendency to purposefully bring attention and awareness to the experiences of the present moment and relate to them in a non-reflexive, non-judgmental way were associated with greater relationship longevity above and beyond the effects of simply being more satisfied in the relationship. As female partner’s mindfulness was not associated with their longitudinal satisfaction, these results might support aforementioned assertions that by being attentive to present experiences and engaging with them in a non-evaluative, non-reactive way, more mindful female partners might minimize corrosive reactionary relational processes that might lead to later deterioration in their dating relationship, thus buffering the possible negative effects of variation in relationship satisfaction. Similarly, at the level of individual facets, female partners’ dispositional tendencies to (a) notice or attend to internal and external experiences, such as sensations, cognitions, and emotions (observing of experience); (b) attend to activities of the moment with purposeful attention rather than behaving automatically or impulsively (acting with awareness); and (c) allow thoughts and feelings to come and go without getting caught up in or carried away by them (nonreactivity to inner experience) were all associated with dating relationship stability (and again above and beyond the effects of their own and their male partners’ relationship satisfaction). In contrast, for male partners, baseline levels of mindfulness were associated with their own longitudinal satisfaction (i.e., actor effects), though this pattern appeared only for two facets and did not extend to relationship stability. Specifically, results suggest that male partners’ tendencies to (a) note or label experiences with words (describing with words) and (b) attend to activities of the moment with purposeful attention rather than behaving automatically or impulsively (acting with awareness) are associated with longitudinal relationship satisfaction in their dating relationships.

Overall, these conglomerate results, as well as the finding that only female partners’ (but not male partners’) satisfaction was significantly associated with the couples’ dating relationship stability, mirror patterns from previous research samples in which female partners might function as the “barometer” of the relationship in different-sex relationships (e.g., Davila et al. 2017; Doss et al. 2003; Kurdek 2009) and that information or characteristics of one partner sometimes predict relationship outcomes better than information from the other partner (e.g., Davila et al. 2017; Kurdek 2009). Furthermore, these results might be congruent with research indicating that males and females often engage in differing communication patterns (Eldridge and Christensen 2002) and report differing emotional experiences (Acitelli and Young 1996) in their romantic relationships, all of which are also associated with levels of mindfulness (Barnes et al. 2007; Wachs and Cordova 2007). Interestingly, these results also complement recent biobehavioral research on the role of mindfulness in relationship processes. In a study that examined how levels of mindfulness facets affect couples’ cortisol responses and subsequent psychological adjustment to relationship conflict, researchers found that only nonreactivity to inner experience predicted female partners’ cortisol responses to a conflict stressor, whereas only describing with words predicted male partners’ responses (Laurent et al. 2013). Moreover, again complimenting results from the present study, Laurent et al. (2013) also found more widespread positive associations between levels of mindfulness facets and psychological adjustment (i.e., less depressive symptoms, greater well-being) for female partners than for male partners. Additionally, as previous research indicates that male partners’ tendency to note or label experiences with words (describing with words) is associated with healthier physiological responses to relationship stressors (Laurent et al. 2013), findings from the present study builds on this previous study and suggest that young adult males who are more able to mindfully communicate about their experiences might also be more attuned to the quality of their relationship and experience greater satisfaction in their dating relationships. In general, these results might provide further impetus for research to examine gender differences in the associations between certain aspects of mindfulness and relationship outcomes over time.

Furthermore, across all models, only one facet of mindfulness demonstrated a significant inter-partner effect, and again, only for young adult female partners. Specifically, these female partners’ nonreactivity to inner experience was positively associated with their male partners’ (but not their own) relationship satisfaction, even beyond male partners’ levels of nonreactivity to inner experience and previous levels of relationship satisfaction. These results are consistent with previous research demonstrating that adult married partners’ dispositional levels of nonreactivity to inner experience are associated with the satisfaction of their partners, but not their own (Lenger et al. 2016), and that increases in the nonreactivity to inner experience facet through mindfulness training are associated with increases in relationship satisfaction for the adult partners of individuals who receive the training, but not their own (Khaddouma et al. 2016). Conceptually, these repeated findings suggest that a greater ability to allow thoughts and feelings to come and go without getting caught up in or carried away by them may incur interpersonal benefits to one’s partner, even when such intrapersonal effects on one’s own relationship satisfaction are not present. By resisting the tendency to reflexively respond to present experiences, individuals might be better able to engage in effective decision-making processes about how to respond or proceed in them. Partners might reap benefits from having a less reactive romantic partner (Davila et al. 2003), as relationship problems are more likely to be effectively ameliorated and less likely to be emotionally damaging when they arise. Thus, for the partners of less reactive individuals, it might be easier to enjoy shared experiences and remain satisfied in the relationship as it continues onward. Importantly, we can have a greater degree of confidence in this finding as it has now been replicated in three different samples, including married longer-term couples, and demonstrated a similar pattern of associations when measured as a baseline trait (e.g., Lenger et al. 2016) and when increased through mindfulness training (e.g., Khaddouma et al. 2016). Moreover, as nonreactivity to inner experience was the only facet to be associated with inter-partner relationship satisfaction and dyadic relationship stability, results from the present study add to the growing body of evidence suggesting that this facet might play a particularly important role in the functioning and longevity of intimate relationships.

Finally, the finding that several facets of mindfulness were not associated with longitudinal relationship satisfaction in the present study offer novel insights into which aspects of mindfulness might play the most robust role in the maintenance of relationship health over time. Regarding actor effects, individuals’ levels of overall mindfulness, observing of experience, nonjudging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience were not associated with longitudinal relationship satisfaction for male or female partners in the present study despite significant associations with relationship satisfaction in previous studies when measured cross-sectionally (Lenger et al. 2016) and after individuals participated in mindfulness training (Khaddouma et al. 2016). However, such findings are similarly reported in a demographically similar sample of dating partners by Barnes et al. (2007), who also found that mindfulness was not associated with relationship satisfaction 10 weeks post-baseline when the baseline levels of satisfaction were controlled. As in Barnes et al. (2007), relationship satisfaction in the present study changed very little over the relatively brief 30-day time span, providing little variation in 30-day post-baseline relationship satisfaction to be explained by potential predictors. Thus, it is possible that mindfulness and additional aspects of mindfulness are associated with longitudinal levels of relationship satisfaction when more variance in satisfaction is available due to changes in relationship quality (e.g., through intervention or natural events) or a greater span of time between measurement time points.

Regarding the lack of partner effects observed in the present study (apart from female partners’ nonreactivity to inner experience), Barnes et al. (2007) also documented significant actor effects of mindfulness on participants’ own communication quality and emotional stress responses to relationship conflict, but no effects on the experience of the other member of the couple. However, in a sample of long-term married partners, nonreactivity to inner experience demonstrated a significant partner effect on relationship satisfaction (as in the present study), but no significant inter-partner associations were observed for other facets (Lenger et al. 2016). Further research is clearly needed to clarify the role of specific aspects of mindfulness in the maintenance of relationship satisfaction over time.

Overall, findings from the present study contribute additional evidence as to the role of mindfulness in the longitudinal satisfaction and stability of young adult dating relationships and provide some direction for future research into which aspects of mindfulness might be most important for promoting relationship longevity. Most significantly, results of the present study indicate that mindfulness might be associated with greater longitudinal relationship stability in young adult relationship formation. Additionally, results of the present study adds to the findings from previous research across a variety of adult and young adult samples indicating that greater mindfulness is associated with generally positive relationship outcomes (e.g., Atkinson 2013; Karremans et al. 2015; Kozlowski 2013) and that particular facets of mindfulness appear to have more robust associations than others with romantic relationship outcomes and adjustment (Khaddouma et al. 2015a, 2016; Laurent et al. 2013; Lenger et al. 2016). Further, the effects of mindfulness on partners’ relationship experiences appear to be more intrapersonal in nature (Barnes et al. 2007; Lenger et al. 2016), apart from nonreactivity to inner experience, which repeatedly demonstrates significant interpersonal effects among romantic partners even in the absence of actor effects across several samples (Khaddouma et al. 2016; Lenger et al. 2016). Lastly, these results might provide further impetus for research to examine gender differences in the effects of certain aspects of mindfulness, as results of echo findings from previous studies indicating that certain facets of mindfulness might have more robust effects on the relationship functioning and experiences of female versus male dating partners (Laurent et al. 2013).

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting results from the present study. Most notably, data from the present study relied on self-report measures of mindfulness, relationship satisfaction, and dissolution. Utilizing self-report procedures to capture and quantify mindfulness might present challenges in partialling out responses based on social desirability versus actual levels of mindfulness, as well as accounting for differences in how items are understood semantically among different groups and populations (see Bergomi et al. 2013). Likewise, previous research has shown that individuals tend to be biased in their reporting of negative aspects of their romantic relationships on self-report measures (Loving and Agnew 2001); thus, certain aspects of relationship satisfaction and stability might have been underreported in the current sample as participants were, on average, relatively highly satisfied in their relationships. Additionally, though the importance of completing the questionnaires independently of their partner was stressed to and consented to by all participants, it is possible that partners influenced each other’s data in ways that were not accounted for in the current study (e.g., discussed items on questionnaires before responding, completed surveys together). Additional safeguards to prevent partner influences on self-report data (e.g., completing surveys in separate rooms) should be considered for future research.

It is also important to note that the sample was composed of mostly White, heterosexual college students involved in an unmarried romantic relationship. Because participants in the present study were relatively highly satisfied, it is possible that interpersonal aspects of mindfulness are most relevant to alleviating negative dyadic processes that were not well represented in our sample. Thus, findings from the present study might not generalize to more diverse populations, other types of dyadic relationships (e.g., married couples, same-sex couples), and relationships of varying levels of satisfaction and relationship distress. It will be important for future research to examine these associations in more diverse samples and test whether these associations generalize to other kinds of dyadic relationships.

Given research indicating theoretical and operational differences between state and trait mindfulness (Thompson and Waltz 2007), it is important to note that the current study utilized assessments of trait mindfulness and examined associations between naturally varying levels of this trait and relationship outcomes. It is currently unknown whether similar associations with relationship stability would emerge if levels of state or trait mindfulness were increased or decreased through meditation or mindfulness interventions. Future research should also utilize alternative methodologies for assessing (e.g., behavioral coding, physiological measures) and altering (e.g., meditation, mindfulness inductions) levels of mindfulness in order determine whether these effects are also present when the construct of mindfulness is examined as a state rather than a trait, and when experimental manipulations are used to induce mindfulness states (e.g., Dickenson et al. 2013).

Longitudinal research often entails participant attrition at study follow-up time points and factors associated with attrition, along with decreases in power to detect significant effects in smaller follow-up sample sizes, can increase the risk for type I and II error (Deeg 2002). Though factors associated with participant attrition at follow-up were included in analyses in an effort to control for these confounds, it is possible that certain participant characteristics that were not accounted for in the current study (e.g., conscientiousness, social desirability, relationship commitment, income) were associated with likelihood of completing follow-up surveys, thus biasing the sample at follow-up time points. Moreover, participant attrition rates were relatively high in the current study, and results should be considered preliminary until additional studies with more rigorous methods to retain participants at follow-up time points can replicate these findings. Additionally, as previously mentioned, variables in the present study were measured at time points that were relatively temporally proximal. As follow-up data was collected only 30 or 60 days from the previous time point, variables such as relationship satisfaction were relatively stable across time points, thus providing less variability to be explained by other potential factors. Future studies might consider examining whether these associations are present when measurements of relationship functioning are more temporally distal.

It is also important to note that statistical associations between mindfulness and longitudinal relationship outcomes observed in the present study were relatively small in magnitude, indicating that mindfulness did not demonstrate particularly strong associations with relationship outcomes compared to other relationship variables reported in previous research (e.g., satisfaction, commitment, communication behaviors; see Karney and Bradbury 1995; Le et al. 2010). Thus, it is likely that the salutary effects of mindfulness on relationship outcomes are a product of interactions with other psychosocial factors or due to a cascade of effects of mindfulness on more complex relationship behaviors that ultimately contribute to healthier relationship functioning (Karremans et al. 2015). Results from the present study should be considered preliminary until future research has replicated these findings in the presence of other psychosocial and relationship factors and with more complex analytic models.

Additionally, the present study tested only whether the relationships of individuals with varying levels of mindfulness were more or less likely to remain intact or dissolve. Thus, the processes and specifics of the relationship dissolution (e.g., who ended the relationship and for what reason) for those that dissolved were not examined in the present study. The next step for research in this area should be to examine whether mindfulness is associated with a greater ability to exit unsatisfactory or unhealthy relationships versus maintain relationship stability despite fluctuations in satisfaction or the presence of problems in the relationship, or perhaps a greater likelihood for more mutually cooperative relationship dissolution decisions with one’s partner. Similarly, the present study did not examine how concordance or similarity in partners’ mindfulness levels contributed to relationship outcomes; thus, future research should examine how similarities and differences in partners’ levels of mindfulness contribute to their relationship health.

Lastly, though estimates of the associations between several aspects of mindfulness and relationship outcomes differed in magnitude between males and females in the current study, multiple aspects of an individual’s life experience vary based on gender identity (i.e., the social construction and correlates of an individual’s sexual identity; see Johnson et al. 2009) and might influence associations between male and female partners’ mindfulness and relationship outcomes in ways that were not accounted for in the present study. It is also important to note that male and females in the current study differed in their initial levels of mindfulness at baseline; thus, it is possible that differences in how male and female partners experience mindfulness or utilize mindfulness in their relationships influenced relationship outcomes in ways not addressed by the present study. Thus, results regarding gender differences in the effects of mindfulness on the relationship outcomes of males and females should be considered preliminary until further research has replicated these findings.

References

Acitelli, L. K., & Young, A. M. (1996). Gender and thought in relationships. In G. J. O. Fletcher & J. Fitness (Eds.), Knowledge structures in close relationships: a social psychological perspective (pp. 147–168). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1269–1287.

Arnett, J. J., & Tanner, J. L. (2006). Emerging adults in America: coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Atkinson, B. J. (2013). Mindfulness training and the cultivation of secure, satisfying couple relationships. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 2(2), 73–94.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

Barnes, S., Brown, K. W., Krusemark, E., Campbell, W. K., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). The role of mindfulness in romantic relationship satisfaction and responses to relationship stress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(4), 482–500.

Bergomi, C., Tschacher, W., & Kupper, Z. (2013). The assessment of mindfulness with self-report measures: existing scales and open issues. Mindfulness, 4(3), 191–202.

Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., White, L. K., & Edwards, J. N. (1985). Predicting divorce and permanent separation. Journal of Family Issues, 6, 331–346.

Braithwaite, S. R., Delevi, R., & Fincham, F. D. (2010). Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships, 17(1), 1–12.

Brem, M. J., Khaddouma, A., Elmquist, J., Florimbio, A. R., Shorey, R. C., & Stuart, G. L. (2016). Relationships among dispositional mindfulness, distress tolerance, and women’s dating violence perpetration a path analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516664317.

Brown, D. B., Bravo, A. J., Roos, C. R., & Pearson, M. R. (2015). Five facets of mindfulness and psychological health: evaluating a psychological model of the mechanisms of mindfulness. Mindfulness, 6, 1021–1032.

Burpee, L. C., & Langer, E. J. (2005). Mindfulness and marital satisfaction. Journal of Adult Development, 12(1), 43–51.

Caldwell, K., Harrison, M., Adams, M., Quin, R. H., & Greeson, J. (2010). Developing mindfulness in college students through movement-based courses: effects on self-regulatory self-efficacy, mood, stress, and sleep quality. Journal of American College Health, 58(5), 433–442.

Christopher, M. S., Neuser, N. J., Michael, P. G., & Baitmangalkar, A. (2012). Exploring the psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 124–131.

Collins, A., & van Dulmen, M. (2006). Friendships and romance in emerging adulthood: assessing distinctiveness in close relationships. In J. J. Arnett & J. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: coming of age in the 21 st century (pp. 219–234). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The actor–partner interdependence model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(2), 101–109.

Cui, M., Fincham, F. D., & Durtschi, J. A. (2011). The effect of parental divorce on young adults’ romantic relationship dissolution: what makes a difference? Personal Relationships, 18(3), 410–426.

Cullen, M. (2011). Mindfulness-based interventions: an emerging phenomenon. Mindfulness, 2(3), 186–193.

Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29.

Davila, J., Karney, B. R., Hall, T. W., & Bradbury, T. N. (2003). Depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction: within-subject associations and the moderating effects of gender and neuroticism. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(4), 557–570.

Davila, J., Wodarczyk, H., & Bhatia, V. (2017). Positive emotional expression among couples: the role of romantic competence. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 6(2), 94–105.

de Bruin, E. I., Topper, M., Muskens, J. G., Bögels, S. M., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) in a meditating and a non-meditating sample. Assessment, 19(2), 187–197.

Deeg, D. J. (2002). Attrition in longitudinal population studies: does it affect the generalizability of the findings? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 55(3), 213–215.

Deng, Y. Q., Liu, X. H., Rodriguez, M. A., & Xia, C. Y. (2011). The five facet mindfulness questionnaire: psychometric properties of the Chinese version. Mindfulness, 2(2), 123–128.

Desrosiers, A., Klemanski, D. H., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013). Mapping mindfulness facets onto dimensions of anxiety and depression. Behavior Therapy, 44(3), 373–384.

Dickenson, J., Berkman, E. T., Arch, J., & Lieberman, M. D. (2013). Neural correlates of focused attention during a brief mindfulness induction. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), 40–47.

Doss, B. D., Atkins, D. C., & Christensen, A. (2003). Who's dragging their feet? Husbands and wives seeking marital therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29(2), 165–177.

Eldridge, K. A., & Christensen, A. (2002). Demand–withdraw communication during couple conflict: a review and analysis. In P. Noller & J. A. Feeney (Eds.), Understanding marriage: developments in the study of couple interaction (pp. 289–322). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Fincham, F. D., & Cui, M. (Eds.). (2010). Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583.

Gambrel, L. E., & Keeling, M. L. (2010). Relational aspects of mindfulness: implications for the practice of marriage and family therapy. Contemporary Family Therapy, 32(4), 412–426.

Gehart, D. R. (2012). Mindfulness and acceptance in couple and family therapy. New York: Springer.

Gillespie, B., Davey, M. P., & Flemke, K. (2015). Intimate partners’ perspectives on the relational effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction training: a qualitative research study. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37(4), 396–407.

Graham, J. M., Diebels, K. J., & Barnow, Z. B. (2011). The reliability of relationship satisfaction: a reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 39–48.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43.

Heeren, A., Douilliez, C., Peschard, V., Debrauwere, L., & Philippot, P. (2011). Cross-cultural validity of the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire: adaptation and validation in a French-speaking sample. European Review of Applied Psychology, 61(3), 147–151.

Johns, K. N., Allen, E. S., & Gordon, K. C. (2015). The relationship between mindfulness and forgiveness of infidelity. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1462–1471.

Johnson, J. L., Greaves, L., & Repta, R. (2009). Better science with sex and gender: facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. International Journal for Equity in Health, 8(1), 1–11.

Jones, K. C., Welton, S. R., Oliver, T. C., & Thoburn, J. W. (2011). Mindfulness, spousal attachment, and marital satisfaction: a mediated model. The Family Journal, 19(4), 357–361.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Delacorte.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1993). Mindfulness meditation: health benefits of an ancient Buddhist practice. In D. Goleman & J. Garin (Eds.), Mind/body medicine (pp. 259–276). Yonkers: Consumer Reports.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3–34.

Karremans, J. C., Schellekens, M. P., & Kappen, G. (2015). Bridging the sciences of mindfulness and romantic relationships a theoretical model and research agenda. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(1), 29–49.

Keng, S. L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 1041–1056.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Khaddouma, A., Gordon, K. C., & Bolden, J. (2015a). Zen and the art of sex: examining associations among mindfulness, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction in dating relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(2), 268–285.

Khaddouma, A., Gordon, K. C., & Bolden, J. (2015b). Zen and the art of dating: mindfulness, differentiation of self, and relationship satisfaction in dating relationships. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 4(1), 1–13.

Khaddouma, A., Gordon, K. C., & Strand, E. (2016). Mindful mates: relational benefits of mindfulness training to mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) participants and their partners. Family Process, 56(3), 636–651.

Kimmes, J. G., Durtschi, J. A., & Fincham, F. D. (2017). Perception in romantic relationships: a latent profile analysis of trait mindfulness in relation to attachment and attributions. Mindfulness, 8, 1328–1338.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kozlowski, A. (2013). Mindful mating: exploring the connection between mindfulness and relationship satisfaction. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 28(1–2), 92–104.

Kurdek, L. A. (2009). Assessing the health of a dyadic relationship in heterosexual and same-sex partners. Personal Relationships, 16(1), 117–127.

Laurent, H., Laurent, S., Hertz, R., Egan-Wright, D., & Granger, D. A. (2013). Sex-specific effects of mindfulness on romantic partners’ cortisol responses to conflict and relations with psychological adjustment. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(12), 2905–2913.

Le, B., Dove, N. L., Agnew, C. R., Korn, M. S., & Mutso, A. A. (2010). Predicting nonmarital romantic relationship dissolution: a meta-analytic synthesis. Personal Relationships, 17(3), 377–390.

Leary, M. R., & Tate, E. B. (2007). The multi-faceted nature of mindfulness. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 251–255.

Lenger, K. A., Gordon, C. L., & Nguyen, S. P. (2016). Intra-individual and cross-partner associations between the five facets of mindfulness and relationship satisfaction. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0590-0.

Levin, M. E., Dalrymple, K., & Zimmerman, M. (2014). Which facets of mindfulness predict the presence of substance use disorders in an outpatient psychiatric sample? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 498–506.

Lorenz, F. O., Wickrama, K. A. S., Conger, R. D., & Elder Jr., G. H. (2006). The short-term and decade-long effects of divorce on women’s midlife health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(2), 111–125.

Loving, T. J., & Agnew, C. R. (2001). Socially desirable responding in close relationships: a dual-component approach and measure. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18(4), 551–573.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2013). Mplus Version 7.11. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Olmstead, S. B., Pasley, K., Meyer, A. S., Stanford, P. S., Fincham, F. D., & Delevi, R. (2011). Implementing relationship education for emerging adult college students: insights from the field. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 10(3), 215–228.

Ponzetti Jr, J. J. (Ed.). (2015). Evidence-based approaches to relationship and marriage education. New York: Routledge.

Pruitt, I. T., & McCollum, E. E. (2010). Voices of experienced meditators: the impact of meditation practice on intimate relationships. Contemporary Family Therapy, 32(2), 135–154.

Raley, R. K., Crissey, S., & Muller, C. (2007). Of sex and romance: late adolescent relationships and young adult union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1210–1226.

Regnerus, M., & Uecker, J. (2010). Premarital sex in America: how young Americans meet, mate, and think about marrying. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rhoades, G. K., Kamp Dush, C. M., Atkins, D. C., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2011). Breaking up is hard to do: the impact of unmarried relationship dissolution on mental health and life satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(3), 366–374.

Roberts, K. C., & Danoff-Burg, S. (2010). Mindfulness and health behaviors: is paying attention good for you? Journal of American College Health, 59(3), 165–173.

Sassler, S. (2010). Partnering across the life course: sex, relationships, and mate selection. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 557–575.

Sbarra, D. A., & Emery, R. E. (2005). The emotional sequelae of nonmarital relationship dissolution: analysis of change and intraindividual variability over time. Personal Relationships, 12(2), 213–232.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74.

Smith, E. L., Jones, F. W., Holttum, S., & Griffiths, K. (2015). The process of engaging in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as a partnership: a grounded theory study. Mindfulness, 6(3), 455–466.

Thompson, B. L., & Waltz, J. (2007). Everyday mindfulness and mindfulness meditation: overlapping constructs or not? Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1875–1885.

Wachs, K., & Cordova, J. V. (2007). Mindful relating: exploring mindfulness and emotion repertoires in intimate relationships. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(4), 464–481.

Whitton, S. W., Weitbrecht, E. M., Kuryluk, A. D., & Bruner, M. R. (2013). Committed dating relationships and mental health among college students. Journal of American College Health, 61(3), 176–183.

Yeh, H. C., Lorenz, F. O., Wickrama, K. A. S., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H. (2006). Relationships among sexual satisfaction, marital quality, and marital instability at midlife. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(2), 339–343.

Funding

This study was funded by a Dissertation Support Grant from the University of Tennessee–Knoxville, Department of Psychology awarded to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK designed and executed the study, conducted the data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. KCG collaborated in the design and writing of the study and edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was funded by a Dissertation Support Grant from the University of Tennessee–Knoxville, Department of Psychology awarded to the first author. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khaddouma, A., Gordon, K.C. Mindfulness and Young Adult Dating Relationship Stability: a Longitudinal Path Analysis. Mindfulness 9, 1529–1542 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0901-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0901-8