Abstract

Recent evidence indicates that mindfulness is associated with adult attachment, such that individuals with a secure attachment style also tend to be more mindful. In the present experiment, we extend prior cross-sectional research by examining whether priming attachment insecurity (anxiety and avoidance) leads to a decrease in state mindfulness and whether this is mediated by decreased state emotion regulation. Priming attachment anxiety led to a decrease in state emotion regulation which, in turn, was associated with decreased state mindfulness. That is, when individuals experience heightened anxiety about relationships and abandonment, they experience difficulties in the regulation of emotion, which reduces capacity for mindfulness. No such effects were found for priming attachment avoidance. Results of the present research provide experimental evidence that attachment anxiety may be related to low mindfulness via difficulties in emotion regulation and provides some preliminary evidence of the social foundations of mindfulness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mindfulness is commonly defined as the process of ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgementally’ (Kabat-Zinn 1994, p. 4). It involves the ability to perceive thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations without becoming overwhelmed by them and without engaging in efforts to avoid or reduce them. Mindfulness can refer to a psychological trait, known as dispositional mindfulness, to a state of awareness or to the practice of cultivating and enhancing mindfulness through meditation (Brown and Ryan 2003; Germer et al. 2005). Much evidence indicates that individuals higher in mindfulness fare better on a wide range of positive psychosocial outcomes (Keng et al. 2011).

Attachment is the affectional bond formed between an infant and a caregiver during the early years of life and is active and influential across the lifespan (Bowlby 1973; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007a). Attachment in adulthood is conceptualized along the two dimensions of anxiety and avoidance. Attachment anxiety refers to intense fear of abandonment in intimate relationships, worry about the availability of significant others, and the tendency to hyperactivate emotion (Fraley et al. 2000; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007a). Attachment avoidance is characterized by discomfort with intimacy and closeness and the tendency to deny attachment needs and deactivate emotion (Fraley et al. 2000; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007a). Attachment security (low anxiety and avoidance) is associated with numerous positive outcomes, whereas attachment insecurity (high attachment anxiety and/or avoidance) is associated with poor outcomes (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007a). Interestingly, researchers have noted that mindfulness is associated with many of the same beneficial outcomes as attachment security (Pepping et al. 2014b; Shaver et al 2007).

Mindfulness and attachment security both predict positive interpersonal relationships (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007a; Pepping et al. 2014a), romantic relationship satisfaction (Kachadourian et al. 2004; Barnes et al. 2007; Pepping and Halford 2016), enhanced well-being (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007a; Brown and Ryan 2003), higher self-esteem (Park et al. 2004; Pepping et al. 2013b; Pepping et al. 2016), less psychopathology (Mikulincer and Shaver 2012; Brown and Ryan 2003), and greater capacity for emotion regulation (Arch and Craske 2006; Creasey et al. 1999; Shaver and Mikulincer 2009). Due to the shared association with many of the same psychosocial outcomes, several researchers have proposed that attachment and mindfulness may be somehow related.

Shaver et al. (2007) first investigated the association between mindfulness and attachment and found that attachment anxiety and avoidance accounted for 42 % of the variance in mindfulness in a group of experienced mindfulness meditators. Several studies have replicated this association between mindfulness and attachment (e.g. Goodall et al. 2012; Pepping et al. 2015b; Walsh et al. 2009). More recently, Pepping et al. (2014b) demonstrated that mindfulness and attachment are related but that the strength of the association differs based on meditation experience. Specifically, the authors found that attachment anxiety and avoidance predicted 18.8 % of the variance in dispositional mindfulness in a group of non-meditators and 43.3 % of the variance in dispositional mindfulness in experienced mindfulness meditators. In brief, there is a well-replicated association between mindfulness and attachment.

Researchers have become increasingly interested in the underlying processes that might explain how attachment and mindfulness are related. Several researchers have argued that individuals high in attachment security may have greater capacity for mindfulness, as they are less consumed by the cognitive and emotional processes that characterize attachment insecurity (Caldwell and Shaver 2013; Ryan et al. 2007; Shaver et al. 2007). Pepping et al. (2013a) proposed that if attachment security enhances capacity for mindfulness, it seems likely that it is the ability to adaptively regulate emotion that may explain this association, as secure individuals are less likely to struggle with the cognitive and emotional processes associated with insecure attachment, which may provide greater capacity for mindfulness. Emotion regulation ‘refers to the processes by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions’ (Gross 1998, p.275).

Much evidence indicates that attachment security is associated with adaptive emotion regulation, whereas insecure individuals display maladaptive strategies (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007a; Shaver and Mikulincer 2009). Individuals high in attachment anxiety hyperactivate emotion and become overwhelmed by difficult emotions, whereas those high in attachment avoidance deactivate emotion and deny or inhibit emotion and emotional needs. Mindfulness is also associated with adaptive emotion regulation (e.g. Arch and Craske 2006; Hayes and Feldman 2004), as it involves an open and receptive awareness of emotion, without becoming overwhelmed by experiences (as in attachment anxiety), or engaging in efforts to avoid emotion (as in attachment avoidance). Thus, it seems likely that emotion regulation may be the mechanism by which attachment and mindfulness are related. Consistent with this proposition, Pepping et al. (2013a) found that heightened attachment anxiety and avoidance each predicted low mindfulness, and these associations were mediated by difficulties in emotion regulation. Similarly, Caldwell and Shaver (2013) found that attachment anxiety predicted low mindfulness, and this association was mediated by rumination and poor attentional control. Attachment avoidance was also associated with low mindfulness, and this association was mediated by thought suppression and poor attentional control.

Despite there being a well-replicated cross-sectional association between attachment and mindfulness, and the mediating role of emotion regulation, to date, very little research has examined these associations experimentally. Ryan et al. (2007) argued that there may be a bidirectional causal association between attachment security and mindfulness, whereby on the one hand, high mindfulness may foster the capacity to remain open and receptive in relationships, and on the other hand, attachment security may increase the capacity for mindfulness, as secure individuals would be less distracted by cognitive and emotional processes associated with insecure attachment.

Longitudinal research is clearly needed to definitively establish causation. However, a recent experimental study does shed some light on this. To examine this bidirectional association, Pepping et al. (2015a) examined whether inducing state mindfulness would increase state attachment security (study 1) and whether priming attachment security would increase state mindfulness (study 2). In study 1, state mindfulness increased in the experimental condition and not in the control, indicating that the manipulation was effective. However, no change emerged in state attachment security. In study 2, state attachment security increased in the experimental condition and not in the control condition, again, indicating that the manipulation was successful. However, no change in state mindfulness emerged. These results clearly demonstrate that there is no direct, immediate, causal association between attachment security and mindfulness. However, in light of recent evidence that the relationship between attachment and mindfulness is largely indirect via emotion regulation (Caldwell and Shaver 2013; Pepping et al. 2013a), researchers may need to examine indirect effects of experimental manipulations.

Some important questions therefore remain unanswered. Firstly, given recent evidence that the association between attachment and mindfulness is indirect via emotion regulation, it is important to examine whether there are indirect effects of attachment on mindfulness via emotion regulation in an experimental setting. Secondly, Pepping et al. (2015a) examined only attachment security manipulations. It is possible that enhancing security did not affect the intervening variable, namely emotion regulation, and thus, no change in mindfulness was observed. The possibility remains that had they primed attachment insecurity (anxiety and avoidance); this would have resulted in decreased emotion regulation, and, in turn, less capacity for mindfulness.

Attachment priming refers to the process of temporarily activating mental representations of attachment figures and has been shown to lead to a range of theoretically relevant outcomes (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007b) and can activate both state attachment security and insecurity (Gillath et al. 2009). If attachment insecurity is related to low mindfulness via emotion regulation difficulties, then priming attachment insecurity (anxiety and avoidance) should lead to decreased state mindfulness via decreased state emotion regulation. It was predicted that participants in the attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance priming conditions would show a decrease in state mindfulness via decreased state emotion regulation. No such changes were expected in the control condition.

Method

Participants

Participants were 117 undergraduates enrolled in an introductory psychology course (36 males and 78 females aged 16–56, M = 23.81 years, SD = 10.27) who participated for course credit.

Procedure

Participants signed up to participate in the study online. Sessions were run in groups of up to ten participants, which were randomly assigned to either an attachment anxiety priming condition (N = 36), an attachment avoidance priming condition (N = 47), or to a neutral control condition (N = 34). Participants completed the pre-manipulation questionnaires that assessed state mindfulness, attachment, and emotion regulation, then completed the experimental manipulation, and finally completed the post-manipulation questionnaires that assessed state mindfulness, attachment, and emotion regulation. Following the post-questionnaires, a positive mood induction was performed to reduce any potential negative impact of the primes. Specifically, participants were asked to write a few sentences about the three best times in their life, which has been used in prior research to induce positive mood.

The primes were adapted from Bartz and Lydon (2004) and have been used successfully in several studies (Carnelley and Rowe 2010; Rowe et al. 2012). Participants in the avoidant priming condition were asked to visualise a relationship in which they felt uncomfortable and where they found it difficult to trust the other person and felt uneasy when the person tried to get too close to them. Participants in the anxious condition were asked to visualise a relationship in which they felt the other person was reluctant to get too close and where they often worried about whether they were loved by the other person. Participants were then given 3 min to visualise this person, using prompting questions, including ‘what was it like to be with this person?’ and ‘how do you feel when you are with this person?’ Participants were then given 3 min to write a few sentences about their thoughts and feelings in relation to their chosen person. In the neutral priming condition, participants were asked to visualise a neutral activity that was unrelated to attachment, namely brushing their teeth. Participants then wrote about the thoughts and feelings related to brushing their teeth. This control condition was chosen as it was unrelated to attachment, mindfulness, or emotion regulation and was therefore unlikely to influence these variables.

Measures

State Attachment

The 21-item State Adult Attachment Measure (SAAM) assesses state attachment along three dimensions: state attachment anxiety, avoidance, and security (Gillath et al. 2009). Higher scores on each subscale reflect higher state attachment anxiety (e.g. ‘I really need to feel loved right now’), security (e.g. ‘I feel loved’), or avoidance (e.g. ‘I would be uncomfortable having a good friend or a relationship partner close to me’). Each of the subscales demonstrates high internal consistency (α = .81–.85 for the anxiety subscale; α = .71–.85 for avoidance subscale; Gillath et al. 2009). The scales also converge with measures of dispositional attachment and display discriminant validity from the positive and negative affect schedule (Gillath et al. 2009). The SAAM displayed high internal consistency in the present sample (α = .85 and .87) for anxiety and avoidance, respectively.

State Mindfulness

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale state (MAAS-state; Brown and Ryan 2003) is a five-item measure of state mindfulness that correlates with dispositional measures of mindfulness and is sensitive to experimental manipulations (e.g. Pepping et al. 2015a). The MAAS-state is generally administered following the completion of a task and requires participants to reflect on their level of mindfulness during the task. In the present research, the task used was completing the questionnaires prior to this scale (e.g. ‘I found it difficult to stay focussed on what was happening in the present’). The MAAS-state has good internal consistency (α = .92; Brown and Ryan 2003) and displayed high internal consistency in the present sample (α = .84).

State Emotion Regulation

The 30-item generalised expectancy for Negative Mood Regulation Scale (NMR; Catanzaro and Mearns 1990) assesses belief that a particular behaviour or cognition will alleviate a negative mood state or induce a positive one. The items refer to emotion regulation strategies that people may use to modulate their emotional arousal (e.g. ‘Telling myself it will pass will help me calm down’, ‘I can do something to feel better’, ‘I’ll be upset for a long time’, and ‘I won’t be able to enjoy the things I usually enjoy’). Because widely used measures of emotion regulation generally assess individuals’ typical, or dispositional, emotion regulation strategies, to assess state emotion regulation, participants were asked to respond based on how they were feeling at that particular moment. In this way, the use of the NMR in the present research assesses individuals’ current access to emotion regulation strategies perceived as effective, which has been identified as an important component of emotion regulation (Gratz and Roemer 2004). The scale has high internal consistency (alpha of .87) and demonstrates discriminant validity from measures of social desirability (Catanzaro and Mearns 1990). The NMR had high internal consistency in the present sample (α = .90).

Data Analyses

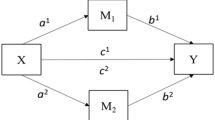

The independent variable (priming condition) is multicategorical, and mediation guidelines have been developed for use with experimental multicategorical data (Hayes 2013). The mediating role of mindfulness was examined using the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013) which tests for mediation in experimental designs. PROCESS provides an estimate of the direct effect of priming condition on mindfulness and generates bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals to estimate the indirect effect of priming condition on mindfulness via state emotion regulation (Hayes 2013). As recommended by Hayes (2013), 10,000 bootstrap samples were used in the present mediation analysis. There were three groups used in this analysis (anxious, avoidant, and control), and therefore, two dummy coded variables were created (control condition as the comparison). In each mediation analysis, a single dummy coded variable is used as the IV, with the other dummy coded variable used as a covariate. The same mediator and DV are used in both analyses. Change scores were calculated for the proposed mediator and the outcome measure. Change scores have been used in previous research testing for mediation with experimental data (e.g. MacKinnon et al. 1991; Wicksell et al. 2010), and we therefore followed these same procedures.

Results

Manipulation Checks

To ensure that the attachment priming manipulations successfully manipulated state attachment, two 2 × 2 (condition × time) mixed ANOVAs were used to assess the change in the two SAAM subscales (anxiety and avoidance).

For state attachment anxiety, there was no significant main effect of time, F (1, 111) = 1.14, p = .291, partial η 2 = .01, but there was a significant interaction between condition and time, F (2, 111) = 4.46, p < .05, partial η 2 = .07. For the anxious priming condition, there was a significant increase from pre (M = 27.86, SD = 7.38) to post (M = 30.08, SD = 8.62) on the SAAM anxiety subscale, t(35) = −3.029, p < .01, whereas no such change occurred in the avoidant condition between pre (M = 30.90, SD = 9.20) and post (M = 30.20, SD = 10.38; t(44) = .895, p = .376) or the control condition between pre (M = 28.88, SD = 9.94) and post (M = 28.71, SD = 10.15; t(33) = .221, p = .826).

For state attachment avoidance, there was a significant main effect of time, F (1, 112) = 6.82, p < .05, partial η 2 = .06, and a significant interaction between condition and time, F (2, 112) = 4.29, p < .05, partial η 2 = .07. For the avoidant condition, there was a significant increase from pre (M = 21.20, SD = 9.87) to post (M = 24.33, SD = 10.65) on the SAAM avoidance subscale, t(44) = −3.510, p < .01. There were no changes in avoidance for the anxious condition between pre (M = 18.50, SD = 7.95) and post (M = 19.92, SD = 9.54; t(35) = −1.518, p = .138) or the control condition between pre (M = 20.65, SD = 9.07) and post (M = 20.15, SD = 8.79; t(33) = .579, p = .566).

Mediation

The relative total, direct, and indirect coefficients for the anxious and avoidance priming conditions, with the MAAS change scores as the DV, and the NMR change scores as the mediator, are displayed in Table 1. As shown in the column labelled ‘NMR’, the relationship between being in the anxious attachment priming condition and NMR change scores was significant, indicating that being in the anxious condition is associated with a decrease in emotion regulation. The association between the NMR change score and MAAS change score (b path) was significant (b = .08, p < .05), indicating that as state emotion regulation increases, mindfulness also increases. The direct and total effects of being in the anxious attachment priming condition on MAAS change scores were not significant, demonstrating no direct effects of anxious priming condition on mindfulness. As shown in the column labelled ‘Indirect’, there was a significant indirect effect of being in the anxious attachment priming condition and MAAS change scores via NMR change scores, CI95 % = −1.04 to −.03, indicating that being in the attachment anxiety priming condition is related to a decrease in state mindfulness via decreased state emotion regulation. No such effects were found for the avoidant attachment condition.

Discussion

The aim of the present experiment was to examine whether priming state attachment insecurity (anxiety and avoidance) would reduce capacity for mindfulness via decreased state emotion regulation. Participants in the anxiety and avoidance priming conditions displayed an increase in state attachment anxiety and avoidance, respectively, indicating that the experimental manipulations were successful. As predicted, being in the anxious attachment priming condition was associated with a reduction in state mindfulness via a reduction in state emotion regulation. No mediation effects were found for attachment avoidance.

The present study extends prior cross-sectional research by providing the first experimental evidence that priming attachment anxiety leads to reduced mindfulness via reduced emotion regulation. That is, when individuals experience heightened anxiety about relationships and abandonment, they experience difficulties in the regulation of emotion, which reduces capacity for mindfulness. This finding is interesting to consider in the context of potential predictors of mindfulness. To date, very little is known about factors that impact on the development of individual differences in mindfulness. Several researchers have proposed that the development of mindfulness may have its roots in early childhood experiences and attachment processes (Ryan et al. 2007; Shaver et al. 2007), and recent cross-sectional evidence supports this proposition (Pepping and Duvenage 2015). Much evidence indicates that attachment orientations develop based on experiences with attachment figures in childhood (Mikulincer and Shaver 2007a). Although our data do not pertain to developmental origins of mindfulness, the finding that increasing state attachment anxiety led to a decrease in state mindfulness is consistent with the proposition that attachment may be one potential antecedent of mindfulness. It is important to note, however, that the present study did not test a potential alternative model whereby experimentally enhancing mindfulness may lead to enhanced security via emotion regulation. Future research should address this possibility. The present study extended upon cross-sectional research demonstrating emotion regulation mediated the attachment-mindfulness association (Caldwell and Shaver 2013; Pepping et al. 2013a) by examining this relationship experimentally. Further research is needed to examine potential alternative pathways between these variables.

Contrary to expectations, priming attachment avoidance did not lead to decreased emotion regulation or mindfulness. There are several potential explanations for this unexpected finding. Firstly, it is possible that emotion regulation strategies used by those high in attachment avoidance were not adequately captured by the NMR. Those high in attachment avoidance tend to suppress negative emotions, which may not involve the consideration of potential strategies for emotion regulation, as assessed by the NMR. Caldwell and Shaver (2013) found the cross-sectional association between attachment avoidance and mindfulness was mediated by thought suppression and poor attentional control, which suggests that using multidimensional measures of emotion regulation may be beneficial. Although such a state measure does not yet exist, future research should examine experimental manipulations of attachment avoidance on emotion regulation using measures that assess state emotion regulation as a multifaceted construct (e.g. Gratz and Roemer 2004).

Secondly, it is possible that the association between attachment avoidance and mindfulness is less clear than originally thought. Although cross-sectional research generally finds an association (e.g. Pepping et al. 2014b; Shaver et al. 2007), Walsh et al. (2009) found that attachment anxiety but not avoidance predicted reduced mindfulness in a regression model. The authors suggested that some features of attachment avoidance such as thought suppression would likely produce a negative association with mindfulness, whereas other features of attachment avoidance such as inhibited processing of threat and non-elaboration of cognitions may produce a positive association between attachment avoidance and mindfulness. Perhaps the lack of change in state mindfulness for those in the avoidance priming condition reflects this complex association. Walsh et al. (2009) proposed that a multifaceted measure of avoidance attachment could clarify this issue, and future research should address this possibility.

Finally, it is interesting to consider the results of the present research in the context of a relatively new construct in the psychological literature, nonattachment. Nonattachment refers to the capacity to relate to experiences with flexibility, without clinging or grasping, and without engaging in efforts to avoid and suppress these experiences (Sahdra et al. 2010). Nonattachment is related to, but distinct from, mindfulness, and those high in attachment anxiety and avoidance also tend to be low in nonattachment. Further, self-reported nonattachment correlates highly with psychological acceptance and negatively with measures of emotion regulation (Sahdra et al. 2010). Thus, it seems likely that a related mediator of the association between attachment insecurity and low mindfulness may be the reduced capacity for nonattachment. Although nonattachment was not assessed in the present study, it may be useful for future research to investigate how this construct relates to the model presented here and in prior studies (e.g. Pepping et al. 2013a).

Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

The finding that state attachment anxiety is related to lower state mindfulness via reduced emotion regulation capacity has important implications. Firstly, the present study provides experimental evidence for the association between attachment anxiety and mindfulness, extending upon prior cross-sectional research. These findings are consistent with, but do not confirm, the proposition that attachment processes may be involved in the development of mindfulness capacity. Longitudinal research is clearly needed to definitively establish causation and provide evidence as to the developmental and social origins of mindfulness.

There are some limitations of this study that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the measure used to assess state emotion regulation did not assess all aspects of emotion regulation proposed in the literature (e.g. Gratz and Roemer 2004). At present, such a state measure does not exist. Here, we used the NMR, a measure of expectancies for negative mood regulation, which assesses access to emotion regulation strategies perceived as effective. However, future research should test the hypotheses of the current study with a multifaceted state measure of emotion regulation. This is particularly important given the evidence that specific emotion regulation strategies differentially mediate the association between attachment insecurity and mindfulness cross-sectionally (Caldwell and Shaver 2013). Nonetheless, the present study sheds light on the indirect effects of access to emotion regulation strategies more broadly.

Secondly, the focus of the present research on state variables was necessary to experimentally investigate associations between these variables; however, it also means that results cannot readily be generalised to dispositional measures of attachment and mindfulness. However, conceptually and empirically, state and dispositional measures have much in common, with dispositional measures referring to the frequent experience of the particular state, occurring for some duration, at a reasonably high level of intensity. Further, the state attachment measure (Gillath et al. 2009) and state mindfulness measure (Brown and Ryan 2003) correlate with dispositional measures. Again, longitudinal research is required to establish causation between attachment and mindfulness. Similarly, the attachment primes were very brief in the present study. Although brief primes have been used successfully in prior research (e.g. Bartz and Lydon 2004; Mikulincer and Shaver 2007b), and our manipulation checks demonstrated the primes were effective, the possibility remains that longer primes may have had stronger impact on attachment avoidance and emotion regulation capacity. This possibility remains to be investigated empirically.

Although the aims of the present research were to extend previous security priming studies by priming attachment insecurity (anxiety and avoidance), and to examine indirect effects via emotion regulation, it would also be beneficial for future research to investigate indirect effects of attachment security priming on state mindfulness via state emotion regulation. All cross-sectional studies to date have examined associations between attachment insecurity (anxiety and avoidance) and mindfulness via emotion regulation, and the present study clearly provides some experimental evidence in support of this model. Nonetheless, future research should also investigate indirect effects of security priming on state mindfulness.

It is also important to consider variation between participants in how readily available mental representations of attachment figures were and how willing and able each participant was to engage in the visualisation primes. Although we used primes that had been validated in prior research and found that the manipulations for anxiety and avoidance were successful in the present research, it is important to keep in mind that there is likely to be variability between participants in the efficacy of such primes.

It is useful to consider the impact of the administration of the State Adult Attachment Measure (SAAM) within the same session given the potential for participants to recall earlier responses and attempt to remain consistent. We administered the SAAM pre and post in order to assess momentary fluctuations in state attachment that result from the manipulations within the experimental session. It was therefore not ideal to administer the pre-SAAM at an earlier session as it would not be possible to attribute pre-post changes in the SAAM to the experimental manipulation. Further, the finding that the SAAM was sensitive to the manipulations of attachment anxiety and avoidance is encouraging. Nonetheless, results should be interpreted with the above limitations in mind.

Findings from the present research demonstrate that experimentally enhancing state attachment anxiety reduces state mindfulness via a reduction in state emotion regulation. This study provides some interesting new evidence for the potential social foundations of mindfulness, though further longitudinal research is needed.

References

Arch, J. J., & Craske, M. G. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(12), 1849–1858. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007.

Barnes, S., Brown, K. W., Krusemark, E., Campbell, W. K., & Rogee, R. D. (2007). The role of mindfulness in romantic relationship satisfaction and responses to relationship stress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(4), 482–500. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00033.x.

Bartz, J., & Lydon, J. (2004). Close relationships and the working self-concept: implicit and explicit effects of priming attachment on agency and communion. Personality and Social Psychology Bullentin, 30(11), 1389–1401. doi:10.1177/0146167204264245.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and Loss: Separation: Anxiety and Anger (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Basic Books Branstrom, Kvillemo, Brandberg & Moskowitz, 2010

Brown, K., & Ryan, R. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Caldwell, J. G., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Mediators of the link between adult attachment and mindfulness. Interpersona, 7(2), 299–310. doi:10.5964/ijpr.v7i2.133.

Carnelley, K., & Rowe, A. (2010). Priming a sense of security: what goes through people’s minds? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 253–261. doi:10.1177/0265407509360901.

Catanzaro, S., & Mearns, J. (1990). Measuring generalised expectancies for negative mood regulation: initial scale development and implications. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54(3-4), 546–563.

Creasey, G., Kershaw, K., & Boston, A. (1999). Conflict management with friends and romantic partners: the role of attachment and negative mood regulation expectancies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(5), 523–543. doi:10.1023/a:1021650525419.

Fraley, R., Waller, N., & Brennan, K. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 350–365. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350.

Germer, C., Siegel, P., & Fulton, P. (2005). Mindfulness and Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Gillath, O., Hart, J., Noftle, E., & Stockdale, G. (2009). Development and validation of a state adult attachment measure (SAAM). Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 362–373. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.12.009.

Goodall, K., Trejnowska, A., & Darling, S. (2012). The relationship between dispositional mindfulness, attachment security and emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 622–626. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.008.

Gratz, K., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the differences in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioural Assessment, 26(1), 41–54.

Gross, J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271.

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. M., & Feldman, G. (2004). Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 255–262. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bph080.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. New York: Hyperion.

Kachadourian, L. K., Fincham, F., & Davila, J. (2004). The tendency to forgive in dating and married couples: the role of attachment and relationship satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 11(3), 373–393. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00088.x.

Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 1041–1056. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006.

MacKinnon, D., Johnson, A., Pentz, M., Dwyer, J., Hansen, W., Flay, B., & Wang, E. (1991). Mediating mechanisms in a school-based drug prevention program: first-year effects of the midwestern prevention project. Health Psychology, 10(3), 164–172.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. (2007a). Adult Attachment: Structure, Dynamics and Change. New York: The Guilford University Press.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. (2007b). Boosting attachment security to promote mental health, prosocial values, and inter-group tolerance. Psychological Inquiry, 18(3), 139–156. doi:10.1080/10478400701512646.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. (2012). Adult attachment orientations and relationship processes. Journal of Family Theory and Review., 4(4), 259–274. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00142.x.

Park, L. E., Crocker, J., & Mickelson, K. D. (2004). Attachment styles and contingencies of self-worth. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(10), 1243–1254. doi:10.1177/0146167204264000.

Pepping, C. A., & Duvenage, M. (2015). The origins of individual differences in dispositional mindfulness. Personality and Individual Difference, 93, 130–136. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.027.

Pepping, C. A., & Halford, W. K. (2016). Mindfulness and couple relationships. In Mindfulness and Buddhist-Derived Approaches in Mental Health and Addiction (pp. 391–411). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Pepping, C. A., Davis, P., & O’Donovan, A. (2013a). Individual differences in attachment and dispositional mindfulness: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 453–456. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.006.

Pepping, C. A., O’Donovan, A., & Davis, P. (2013b). The positive effects of mindfulness on self-esteem. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(5), 376–386. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.807353.

Pepping, C. A., O’Donovan, A., Zimmer-Gembeck, & Hanisch, M. (2014a). Is emotion regulation the process underlying the relationship between low mindfulness and psychosocial distress? Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 130–138. doi:10.1111/ajpy.12050.

Pepping, C. A., O’Donovan, A., & Davis, P. J. (2014b). The differential relationship between mindfulness and attachment in experienced and inexperienced meditators. Mindfulness, 5, 392–399. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0193-3.

Pepping, C. A., Davis, P., & O’Donovan, A. (2015a). The association between state attachment security and state mindfulness. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0116779. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116779.

Pepping, C. A., O’Donovan, A., Zimmer-Gembeck, M., & Hanisch, M. (2015b). Individual differences in attachment and eating pathology: the mediating role of mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 75, 24–29. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.040.

Pepping, C. A., Davis, P. J., & O’Donovan, A. (2016). Mindfulness for cultivating self-esteem. In Mindfulness and Buddhist-Derived Approaches in Mental Health and Addiction (pp. 259–275). Springer International Publishing: Switzerland.

Rowe, A., Carnelley, K., Harwood, J., Micklewright, D., Russouw, L., Rennie, C., & Liossi, C. (2012). The effect of attachment orientation priming on pain sensitivity in pain-free individuals. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29, 488–507. doi:10.1177/0265407511431189.

Ryan, R., Brown, K., & Creswell, J. (2007). How integrative is attachment theory? Unpacking the meaning and significance of felt security. Psychological Inquiry, 18(3), 177–182. doi:10.1080/10478400701512778.

Sahdra, B. K., Shaver, P. R., & Brown, K. W. (2010). A scale to measure nonattachment: A Buddhist complement to Western research on attachment and adaptive functioning. Journal of personality assessment, 92(2), 116–127. doi:10.1080/00223890903425960.

Shaver, P., & Mikulincer, M. (2009). Adult attachment strategies and the regulation of emotion. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 446–465). New York: Guilford Press.

Shaver, P., Lavy, S., Saron, C., & Mikulincer, M. (2007). Social foundations of the capacity for mindfulness: an attachment perspective. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 264–271. doi:10.1080/10478400701598389.

Walsh, J. J., Balint, M. G., Smolira, D. R., Frederickson, L. K., & Madsen, S. (2009). Predicting individual differences in mindfulness: the role of trait anxiety, attachment anxiety and attentional control. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 94–99. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.008.

Wicksell, R., Olsson, G., & Hayes, S. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a mediator or improvement in acceptance and commitment therapy for patients with chronic pain following whiplash. European Journal of Pain, 14(10), 1059–1072. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.05.001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants

All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Melen, S., Pepping, C.A. & O’Donovan, A. Social Foundations of Mindfulness: Priming Attachment Anxiety Reduces Emotion Regulation and Mindful Attention. Mindfulness 8, 136–143 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0587-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0587-8