Abstract

Mindfulness meditation leads to a range of positive outcomes, yet little is known about the motivation behind choosing to practice meditation. This research investigated reasons for commencing and continuing mindfulness meditation. In both qualitative and quantitative analyses, the most frequently cited reason for commencing and continuing meditation practice was to alleviate emotional distress and enhance emotion regulation. A substantial proportion of participants also reported continuing meditation to enhance well-being, though very few commenced or continued meditation practice for spiritual or religious reasons. In brief, the overwhelming majority of participants in the present study reported practicing mindfulness to alleviate emotional distress. Further research is needed to examine reasons for meditation across more diverse samples, and whether reasons for meditation differentially predict outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mindfulness is commonly defined as the process of “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally” (Kabat-Zinn 1994, p. 4). Mindfulness meditation, therefore, involves the intentional self-regulation of attention to present moment experience, coupled with a non-judgmental and accepting stance toward whatever may arise (Baer 2003; Kabat-Zinn 1990; Kabat-Zinn 1994). Although there are other forms of meditation, including concentrative meditation and guided meditation, here we focus exclusively on mindfulness meditation.

Much evidence indicates that mindfulness meditation leads to a range of positive outcomes (Keng et al. 2011), yet little is known about the reasons individuals choose to practice mindfulness meditation. Most of the empirical literature has examined mindfulness meditation in clinical interventions (Keng et al. 2011), whereas little research has examined mindfulness for its original goal, namely personal growth and self-liberation (Shapiro 1994). According to Shapiro (1992, 1994), there are three goals or reasons for meditation: self-regulation, self-liberation, and self-exploration. Self-regulation refers to the motivation to reduce stress and pain and enhance well-being, whereas self-exploration refers to the use of meditation to increase self-awareness and self-understanding. Finally, self-liberation refers to the practice of mindfulness meditation for spirituality reasons or personal growth (Shapiro 1992; Shapiro 1994).

Shapiro (1992) examined goals and expectations for practicing meditation in a group of 27 meditators who had signed up for an intensive Vipassana meditation retreat. Ten participants (37 %) reported self-regulation as their motivation, nine (33.3 %) identified self-liberation, six (22.2 %) identified self-exploration as their primary motivation, and two were classified as identifying ‘other’ reasons. Interestingly, reasons for practicing meditation shifted somewhat from self-regulation, to self-exploration, to self-liberation as meditation experience increased, with experienced meditators more likely to identify self-liberation as their motivation.

Carmody et al. (2009) also examined reasons for engaging in mindfulness meditation practice in a sample of 309 participants attending a mindfulness-based stress reduction program for stress-related difficulties. Based on the research of Shapiro (1992), participants were asked to rate the importance of two reasons pertaining to self-regulation, two reasons pertaining to self-exploration, and two reasons pertaining to self-liberation. The maximum score for each type of intention was 10. Results revealed high levels of intention for self-regulation (9.34), self-exploration (8.35), and self-liberation (8.26). Furthermore, intentions were largely unrelated to outcome measures of psychological distress, a finding difficult to interpret easily because of the low variability of the intention ratings.

In brief, much evidence reveals mindfulness meditation enhances a wide range of positive outcomes, yet little is known about the reasons people choose to practice meditation. There is good reason to predict there may be a range of reasons individuals choose to practice meditation. However, the only two empirical studies to investigate this have relied on either very small samples of highly experienced meditators in intensive retreats (Shapiro 1992) or samples characterized by stress-related illness (Carmody et al. 2009). It is therefore important to examine reasons for practicing meditation in larger samples not characterized only by individuals experiencing stress-related concerns.

The aim of the present research was to identify reasons people choose to commence mindfulness meditation practice, and reasons for continuing to practice, in two phases: (a) a qualitative analysis of open-ended responses pertaining to reasons for commencing and continuing meditation practice, and (b) a quantitative analysis of reasons for commencing and continuing meditation practice. The use of qualitative analysis was appropriate as an initial step. Thematic analysis explores, identifies, and analyzes themes from qualitative data, independent of theory, or preconceived hypotheses (Braun and Clarke 2006). We therefore asked participants open-ended questions relating to their reasons for engaging in mindfulness meditation, followed by quantitative questions. No specific hypotheses were developed as the goal was to identify themes relating to reasons for engaging in meditation.

Method

Participants

Participants were 190 adults attending a large urban university (149 female, 41 male) ranging in age from 17 to 53 (M = 21.34, SD = 5.76) who had practiced mindfulness meditation. Of these, 71 participants (57 female, 14 male) ranging in age from 17 to 41 (M = 21.45, SD = 4.94) reported having a current mindfulness meditation practice. Most current meditators (n = 58) practiced at least weekly, with the remainder practicing less than once per week. Thirty-three participants had practiced meditation for less than 1 year, 29 for between 1 and 5 years, and 9 for over 5 years. The remaining 119 (92 female, 27 male) participants, ranging in age from 17 to 53 (M = 21.27, SD = 6.22), reported having practiced mindfulness meditation previously, but no longer practiced. There were no significant differences in age or gender breakdown between those with a current mindfulness practice and those with prior meditation experience. Participants were undergraduate psychology students participating for 1 h experimental credit.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through an online advertisement on the university research participation website, where the inclusion requirement of having experience in mindfulness meditation was explained. Participants were informed the research was designed to assess reasons for engaging in mindfulness meditation.

Measures

Participants completed an online questionnaire. After providing demographic information, participants responded to two open-ended questions that were subsequently coded for the qualitative analysis. The first question was asked to all participants (n = 190): “Why did you first choose to start practicing mindfulness meditation? What were your reasons?” The second question was asked only to those participants who reported having a current mindfulness meditation practice: “What are your reasons for continuing to practice mindfulness meditation?”

Participants were next asked to respond to a series of questions about their reasons for meditation. All participants responded to the following question: “Why did you start practicing mindfulness meditation?” and were asked to rate how important were each of the following reasons: relaxation; reduce anxiety; feel calmer; improve interpersonal relationships; reduce/manage physical pain; regulate my emotions (manage emotions more effectively); manage difficult thoughts; increase concentration and attention; spiritual or religious reasons; and I wanted to learn more about mindfulness/I was curious about mindfulness meditation. Initially participants were asked to respond to these on a 7-point scale, ranging from not important to very important. We subsequently collapsed responses into three discrete groups: “little to no importance”, “moderate importance”, and “major importance” for ease of interpretation. Scores of 1 reflected no importance, and scores of 2–3 reflected little importance. Very few participants rated potential reasons at these levels, thus we collapsed these three scores to reflect the category of “little to no importance”. Scores of 4–5 were coded as “moderate importance”, and scores of 6–7 were coded as “major importance.”

Participants with a current practice also responded to the following question: “Why do you continue to practice mindfulness meditation?” by rating the importance of each of the following reasons: relaxation; reduce anxiety; feel calmer; improve interpersonal relationships; reduce / manage physical pain; regulate my emotions (manage emotions more effectively); manage difficult thoughts; increase concentration and attention; spiritual or religious reasons; and I continue to learn about myself through mindfulness. These were scored using the same method described above. Importantly, these questions were asked after the open-ended qualitative questions so as to not influence responses to the open-ended questions.

Data Analyses

For the qualitative component, an inductive thematic analysis was used to code and analyze qualitative responses (Braun and Clarke 2006; 2013; Richards and Morse 2007). Responses were coded at multiple themes when a single response tapped multiple concepts. For the quantitative component, the frequency with which participants endorsed particular reasons for commencing and continuing meditation practice were examined, and t tests were performed to examine differences between groups based on meditation experience.

Results

Qualitative Analyses

A detailed description of this analysis can be obtained from the first author. The major findings are presented here. Analysis of the reasons for commencing mindfulness meditation practice revealed four themes:

-

(i)

Reduction of negative experiences. Most responses (94.74 %) referred to beginning mindfulness meditation to cope with or reduce negative experiences, especially negative emotional experiences involving stress, anxiety, panic, and depression.

-

(ii)

Well-being. Many respondents (31.05 %) referred to the use of mindfulness meditation as a tool for enhancing aspects of their lives, such as increased happiness, greater self-awareness, improved performance, and greater alertness and concentration. Importantly, responses at this theme were associated with the use of mindfulness to attain a desired, positive state or outcome rather than to reduce a negative state or outcome.

-

(iii)

Introduction by an external source. Beginning mindfulness meditation on the recommendation of another person was given as an important reason by a substantial minority of participants (28.42 %).

-

(iv)

Religion/spirituality. A small number of participants (6.32 %) mentioned beginning meditation for spiritual or religious reasons. All those who named a religion referred to Buddhism.

Analysis of reasons for continuing mindfulness meditation practice also revealed four themes:

-

(i)

Reduction of negative experiences. Most respondents (95.77 %) commented that continuing mindfulness meditation practice was helpful in reducing negative experiences and managing such things as anger, anxiety, stress, and tension headaches.

-

(ii)

Well-being. Many (74.65 %) reported that continued practice was associated with greater happiness and improved psychological health and life satisfaction.

-

(iii)

Perception of effectiveness. Some (18.31 %) mentioned that they continued meditating because it was useful or beneficial, without specifying particular benefits (e.g., “I have found it very helpful”).

-

(iv)

Religion/spirituality. A small number (4.23 %) reported continued practice for religious and spiritual reasons.

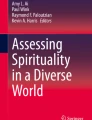

Quantitative Results

Ratings of the importance of various reasons for beginning and continuing mindfulness meditation are presented in Figs. 1 and 2. As can be seen, the four top reasons for both beginning and continuing mindfulness meditation practice were to feel calmer, relaxation, to reduce anxiety, and to regulate emotions more effectively. In contrast, very few participants reported commencing or continuing mindfulness meditation for spiritual or religious reasons.

Next, we compared current meditators who have practiced for less than 1 year (n = 33) with current meditators who have practiced for more than 1 year (n = 36) across each of the 10 reasons. A series of independent samples t tests were performed with alpha set at p < 0.005 to account for multiple tests. Results revealed less experienced meditators were more likely to have commenced (t (67) = 3.54, p = 0.001) and continued (t (67) = 3.21, p = 0.002) mindfulness meditation practice to reduce physical pain compared their more experienced counterparts. No other significant differences emerged.

Discussion

The results of the present research revealed marked similarity in the reasons for both beginning and continuing the practice of mindfulness meditation, a similarity evident in both the qualitative and quantitative data. The vast majority of participants began practicing mindfulness meditation to reduce negative emotional experiences, to manage their emotions more effectively, and to feel calmer, and these same factors were responsible for the continued practice of mindfulness meditation.

Another major reason for practicing mindfulness meditation was to enhance well-being, including happiness, self-awareness, alertness, and concentration. Interestingly, substantially more participants reported well-being as a key reason for continuing mindfulness practice than for commencing mindfulness practice, perhaps indicating that as individuals gain greater experience, they become more aware of the benefits of mindfulness to also increase health and well-being. This is consistent with Shapiro’s (1992) research that as meditation experience increased, participants moved from engaging in mindfulness for self-regulation purposes towards self-exploration and self-liberation purposes (e.g., for personal growth, self-understanding, liberation, or spirituality). Similarly, in the quantitative analyses, meditators with less experience (less than 12 months) were more likely to practice mindfulness to reduce physical pain compared to those with more meditation experience. This finding is certainly consistent with the idea that as experience increases, meditators move more towards self-exploration and self-liberation. However, it is important to note that this was the only significant difference between these two groups, and future research is needed to replicate this finding to ensure it is indeed a reliable pattern.

Very few participants in the present sample reported practicing mindfulness for its original purpose; namely spiritual or religious reasons. Given that this research was conducted in a large university in a western country, perhaps the specific population may influence results. Most of the Western literature on mindfulness has focused on the use of mindfulness in the context of therapy, rather than for spiritual purposes. Perhaps different reasons for practicing mindfulness meditation would emerge in other cultures, and in samples with greater mindfulness meditation experience.

As previously mentioned, there was marked similarity in the findings from the qualitative and quantitative data. Interestingly, however, in the quantitative analysis many reported they continue to practice mindfulness because they continue to learn about themselves, and because it has beneficial effects on relationships. These were not identified as themes within the qualitative analysis, which may indicate that these two reasons were not particularly salient when asked to specify reasons in general. Nonetheless, when asked explicitly about these reasons, more than half of participants endorsed learning about themselves and improved relationships as reasons for continuing.

Because the aim of the qualitative component of was to assess and analyze themes, consistent with thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2013), we did not use Shapiro’s (1992) work to inform our coding of responses. However, our results are remarkably similar, and the key themes emerging from the qualitative and quantitative analyses support Shapiro’s structure of intentions for meditation practice described earlier. Most engaged in mindfulness for self-regulation. Specifically, themes relating to reducing negative experiences, and enhancing well-being, are consistent with the self-regulation intention defined by Shapiro (1992, 1994). The themes pertaining to increased self-awareness, clarity, and learning about oneself, are consistent with Shapiro’s self-exploration intention. Fewer participants engaged in mindfulness meditation for these reasons. Finally, the theme relating to spiritual or religious reasons clearly corresponds to Shapiro’s self-liberation intention. However, in the present research, very few reported engaging in mindfulness for self-liberation reasons. The present sample was a sample of young adults likely to be relatively new to the practice of mindfulness. It seems possible that as they continue to practice mindfulness, their reasons for doing so may shift toward self-liberation. However, this remains to be investigated empirically.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to acknowledge. First, participants were asked to retrospectively recall reasons for commencing meditation. The retrospective reports of reasons for commencing mindfulness and current reports of reasons for continuing mindfulness were generally very similar, which may reflect the influence of current perceptions. However, there were also some clear distinctions which are suggestive of validity of responses. The only way in which reasons for commencing mindfulness practice can be definitively determined is to assess these reasons prior to the commencement of mindfulness practice, and future research should address this question.

Reasons for meditation specified in the quantitative component were not exhaustive, and some may choose to engage in meditation for other reasons. However, the inclusion of open-ended qualitative questions meant that any additional information was captured in the qualitative component. We asked the open-ended qualitative questions prior to presenting the list of ten reasons for engaging in meditation to prevent these researcher-derived reasons from influencing open-ended responses. Nonetheless, the possibility remains that participant responses to such open-ended questions may influence responding to the list of questions as participants may be motivated to remain consistent. Further, participants were not asked whether their reasons for practicing mindfulness meditation referred to formal mindfulness retreats, accessing mindfulness teachers, or to private meditation. Future research should consider reasons for practicing meditation across a range of contexts.

The sample was a fairly homogenous group of young adults in a Western country, and results cannot be assumed to generalize to other groups of meditators. Similarly, females were overrepresented, and results should be interpreted with this in mind. Future research is needed to examine reasons for meditation across broader, more representative samples. Nonetheless, the present research provides important information pertaining to reasons for meditation in meditators in a Western country.

Future research is needed to examine the trajectory of engagement in mindfulness meditation longitudinally to examine intentions more accurately, and to assess potential change in intentions as meditation experience increases over time. Perhaps the most critical question that remains to be addressed, however, is whether reasons for practicing mindfulness meditation influence the outcome of such practices. It seems possible that mindfulness meditators who commence meditation practice for self-regulation reasons might benefit differently than those practicing for self-regulation or self-liberation reasons. Shapiro and colleagues (2006) argue that intentions are critically important as they remind an individual of their reasons for practicing meditation, though to date there is limited evidence to support this proposition (Shapiro 1992). If reasons for practicing meditation do indeed influence outcome, this would suggest that assessing reasons for meditation at the beginning of mindfulness-based interventions may be important. In brief, further research is needed to examine reasons for mindfulness meditation longitudinally across representative samples, and whether the intention behind practicing meditation influences outcome.

References

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract, 10(2), 125–43. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg015.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage.

Carmody, J., Baer, R. A., Lykins E., & Olendzki, N. (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness‐based stress reduction program. J Clin Psychol, 65, 613–26. doi:10.1002/jclp.20579.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Delacorte.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion.

Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin Psychol Rev, 31, 1041–56. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006.

Richards, L., & Morse, J. (2007). Readme First for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks Calif.: Sage Publications.

Shapiro, D. H. (1992). A preliminary study of long-term meditators: goals, effects, religious orientation, cognitions. J Transpers Psychol, 24, 23–39.

Shapiro, D. H. (1994). Examining the content and context of meditation: a challenge for psychology in the areas of stress management, psychotherapy, and religion/values. J Humanist Psychol, 34, 101–35. doi:10.1177/00221678940344008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pepping, C.A., Walters, B., Davis, P.J. et al. Why Do People Practice Mindfulness? An Investigation into Reasons for Practicing Mindfulness Meditation. Mindfulness 7, 542–547 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0490-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0490-3