Abstract

Both dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness training may help to uncouple the degree to which distress is experienced in response to aversive internal experience and external events. Because emotional reactivity is a transdiagnostic process implicated in numerous psychological disorders, dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness training could exert mental health benefits, in part, by buffering emotional reactivity. The present studies examine whether dispositional mindfulness moderates two understudied processes in stress reactivity research: the degree of concordance between subjective and physiological reactivity to a laboratory stressor (study 1) and the degree of dysphoric mood reactivity to lapses in executive functioning in daily life (study 2). In both studies, lower emotional reactivity to aversive experiences was observed among individuals scoring higher in mindfulness, particularly non-judging, relative to those scoring lower in mindfulness. These findings support the hypothesis that higher dispositional mindfulness fosters lower emotional reactivity. Results are discussed in terms of implications for applying mindfulness-based interventions to a range of psychological disorders in which people have difficulty regulating emotional reactions to stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Emotional reactivity to stress is a transdiagnostic process that may be successfully targeted by mindfulness-based interventions (Greeson et al. 2014). A recent review paper integrating both traditional Buddhist writings and psychological literatures defined equanimity as an “even-minded” stance that gives rise to “non-reactivity” to experiences and can “aid in the recovery from emotional and physical stress, helping the individual return rapidly to a state of balance” and highlighted the value of studying equanimity as an outcome in mindfulness research (Desbordes et al. 2015). There are at least two traditions in examining the construct of emotional reactivity in psychological research. Laboratory reactivity studies typically involve exposing participants to a stressful or challenging experience and then calculating the degree of change in self-reported emotional states and/or physiological states relative to a pre-stressor baseline (Chida and Hamer 2008). A second approach typically assesses emotional reactivity using intensive longitudinal data, such as a daily diary study, to measure the degree to which ratings of emotional distress are elevated following the occurrence of naturally occurring stressful events relative to distress ratings obtained after a period when stressful events did not occur or occurred to a lesser degree (Bolger and Schilling 1991; Bolger and Laurenceau 2013). Both forms of emotional reactivity are important to study given their prospective link to subsequent physical and mental health problems. Specifically, greater reactivity to laboratory stressors is associated with subsequent poor cardiovascular health (Chida and Steptoe 2010; Lovallo and Gerin 2003; Treiber et al. 2003) and daily mood reactivity to stressful events has been shown to prospectively predict increases in depression symptoms (O’Neill et al. 2004; Parrish et al. 2011).

A consistent finding across several lines of research reviewed below is that mindfulness moderates the association between stressful, aversive experiences and subjective distress. First, laboratory experiments in which individuals are exposed to either a stressor or control condition suggest that dispositional mindfulness may uncouple the stressor-distress association. Specifically, relative to individuals who score high in dispositional mindfulness (assessed with the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale [MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003]), individuals who score low in mindfulness show greater emotional and physiological reactivity to a public speaking task (Brown et al. 2012) and greater defensive responding to an existential threat (Niemiec et al. 2010).

Second, mindfulness training of various lengths can aid in reducing emotional reactivity. For instance, a brief 15-min mindfulness induction helped to reduce emotional reactivity to repetitive thoughts in college students (Feldman et al. 2010). Specifically, relative to individuals assigned to practice two other stress management exercises, individuals assigned to practice a mindful breathing exercise showed a relatively weaker association between the frequency of repetitive thoughts during the 15-min practice period and degree to which thoughts were experienced as upsetting. Two recent randomized clinical trials (RCTs) examined the effects of much more intensive mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) on stress reactivity among patients with generalized anxiety disorder (Hoge et al. 2013) and depression (Britton et al. 2012). In both studies, which administered a standardized public speaking stressor pre- and post-treatment, greater reductions in emotional reactivity were found for participants who received MBI relative to a control group.

MBIs may also help people to stay well in the period of time following treatment by both attenuating reactivity itself as well as attenuating the effects of reactivity on subsequent symptoms. Witkiewitz and Bowen (2010) compared the effects of mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP) to treatment-as-usual for substance use and found that the association of residual depression symptoms post-treatment predicted cravings and subsequent use in the treatment as usual group; however, the depression-craving association was attenuated in the group who received mindfulness training. A second RCT (Kuyken et al. 2010) compared mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) vs. maintenance anti-depressant medication for recurrent major depression and found a relative advantage for mindfulness training in terms of attenuating the effects of reactivity on later depression. Specifically, the effect of post-treatment cognitive reactivity (increases in negative thoughts following a laboratory sad mood induction) on severity of subsequent depression symptoms at 15-month follow-up was moderated by treatment condition. The association between this previously observed risk factor (cognitive reactivity) and subsequent depression severity was only observed in those who did not receive mindfulness training, suggesting that mindfulness training uncoupled reactivity from symptom manifestation over time.

Third, outside of laboratory experiments and clinical trials, naturalistic studies of stress reactivity to life events also suggest that mindfulness may help to uncouple the association of aversive experience and emotional distress. In a 7-day daily diary study, adolescents lower in dispositional mindfulness (specifically non-judging and non-reactivity facets of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire [FFMQ; Baer et al. 2006]) showed a stronger positive association between number of daily stressors and daily depressed affect than those with higher mindfulness scores (Ciesla et al. 2012). Similarly, cross-sectional studies also showed that dispositional mindfulness (assessed with the MAAS) moderated the effect of recent hassles on depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in an adolescent sample (Marks et al. 2010), whereas Bränström et al. (2011) found that mindfulness (assessed with FFMQ act with awareness and non-reactivity scales) moderated the association of perceived stress with depression symptoms and perceived physical health in a large adult sample. Finally, in a large sample of mostly female adult public service providers, the positive association of adverse childhood events and poor adult health-related quality of life was moderated by mindfulness as assessed by the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R; Feldman et al. 2007) (Whitaker et al. 2014). These results suggest that the previously documented association of adverse childhood events and poor adult health may be buffered by dispositional mindfulness.

Across laboratory, clinical intervention, and naturalistic studies, the stress-distress association is dampened, buffered, or uncoupled among individuals higher in dispositional mindfulness and those who have received mindfulness training. Conversely, lower levels of mindfulness may contribute to greater reactivity to stress and, by extension, could increase vulnerability to psychological disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and substance use, which involve excessive emotional reactivity. Although experimental, correlational, and interventional evidence has converged to support the buffering hypothesis of mindfulness and mindfulness training on emotional and physiological reactivity, no studies to our knowledge have examined the effect of dispositional mindfulness on uncoupling emotional reactivity from physiological reactivity to stress in the laboratory. Concordance between emotional reactivity and physiological reactivity has been identified as a potential transdiagnostic marker of psychopathology (Calvo and Miguel-Tobal 1998; Coifman et al. 2007; Marx et al. 2012; Sallis et al. 1980; Zahn et al. 1991), and identifying individual differences that account for this phenomenon has been identified as a valuable research aim (Bernstein et al. 1986).

Moreover, no studies to date have investigated whether dispositional mindfulness can uncouple emotional reactions from executive functioning lapses in everyday life. Executive function (EF)—defined as self-regulation to achieve goals—has far-ranging impact on daily functioning and quality of life and encompasses a broad array of self-directed cognitions and actions including problem-solving, working memory, impulse control, self-motivation, and emotion regulation (Barkley 2012a). Individuals who experience greater EF difficulties report elevated depression symptoms in cross-sectional studies (Feldman et al. 2013; Knouse et al. 2013; Wingo et al. 2013). Prior naturalistic studies of mindfulness as a moderator of emotional reactivity to stressors have largely focused on reactivity to stressful external events such as poor academic performance, interpersonal conflict, and daily hassles (e.g., Ciesla et al. 2012, Marks et al. 2010); however, in both theoretical accounts and in meditation practice, mindfulness is regarded as an adaptive response to unwanted internal events (Baer, 2010; Dorjee, 2010; Grabovac et al. 2011; Hayes and Feldman, 2004). EF lapses such as failure to regulate attention, memory, or inhibition may be conceptualized as an unwanted cognitive (i.e., internal) event. Individuals who are more mindful may respond to such internal lapses with an attitude of acceptance and self-compassion that facilitates equanimity, whereas those low in mindfulness may respond to these internal lapses with rumination, self-criticism, and sustained emotional reactivity (Vago and Silbersweig 2012).

The present studies seek to advance the field by examining whether trait mindfulness moderates the association of two forms of aversive experiences—experimentally induced stress in the laboratory and naturally occurring executive functioning lapses (a form of cognitive stress) in daily life—and subsequent emotional distress. We hypothesized that mindfulness will buffer the association between physiological arousal and subsequent negative affect in the context of a laboratory stressor (study 1) and the association between daily executive functioning lapses and changes in daily dysphoric affect (study 2), consistent with the experience of “stress without distress” (Selye 1974).

Study 1: Mindfulness and the Association of Subjective and Physiological Reactivity

Previous laboratory studies have established that both dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness training are associated with lower reactivity to standardized laboratory stressors. Specifically, individuals with higher dispositional mindfulness scores show reduced subjective as well as physiological reactivity to a variety of physical, interpersonal, and emotional stressors (Arch and Craske 2010; Brown et al. 2012; Kadziolka et al. 2015; Skinner et al. 2008). Similarly, mindfulness training of various lengths has also been found to produce reduced physiological and subjective reactivity to various laboratory stressors (Creswell et al. 2014; Britton et al. 2012; Hoge et al. 2013, Nyklíček et al. 2013, Steffen and Larson 2014).

Beyond studies of mindfulness and reactivity, a frequent finding in laboratory stressor research more broadly is the relatively modest correlation between physiological markers of arousal (e.g., heart rate) and subjective distress (e.g., self-report measures of negative affect) (Feldman et al. 1999). Although this finding is often discussed as a methodological issue, others have argued that elucidating factors such as individual differences that contribute to relative concordance and discordance between physiological and subjective arousal is a valuable research aim (Bernstein et al. 1986). Previous research suggests that rates of physiological-subjective concordance are higher in clinical vs. non-clinical samples (Sallis et al. 1980), high vs. low trait anxious undergraduates (Calvo and Miguel-Tobal 1998), children genetically at-risk for psychopathology vs. children at low genetic risk (Zahn et al. 1991), and individuals with PTSD diagnosis compared to individuals without a PTSD diagnosis (Marx et al. 2012). Taken together, these findings suggest that high concordance may be a marker of psychopathology. This interpretation is further bolstered by a longitudinal study in a community sample finding that individuals with relatively lower concordance between heart rate and subjective distress during a laboratory assessment show lower levels of psychopathology, better physical health, and higher peer-rated adjustment (Coifman et al. 2007). Given that dispositional mindfulness is associated with reduced emotional reactivity of both self-reported and physiological markers of emotion, it is a promising candidate to study as an individual difference that may contribute to the relative concordance vs. discordance between physiological arousal and subjective distress. However, mindfulness has not yet been examined in this context.

The present study used a laboratory design to examine the effects of a stressful task on changes in both self-report distress and physiological arousal as indexed by measures of heart rate and skin conductance level. These two physiological indices are widely used in previous physiological-subjective concordance studies. Furthermore, prior laboratory stress studies have found that individual differences in mindfulness are associated with lower reactivity in both heart rate (Skinner et al. 2008) and skin conductance (Kadziolka et al. 2015). We hypothesized that mindfulness will moderate the association of subjective arousal (negative affect) and physiological reactivity to a laboratory stressor such that subjective-physiological concordance will be higher among individuals low in mindfulness. Among individuals higher in mindfulness, the concordance between physiological arousal and subjective distress will be uncoupled (significantly weaker).

Method

Participants

One-hundred female undergraduates attending a woman’s college participated in a single laboratory session in exchange for course credit. Due to technical problems, psychophysiological data were not recorded for three participants. Analyses were performed on the remaining sample (N = 97, age M = 20.48 (4.12); 75.3 % White, 15.5 % Asian/Pacific Islander, 4.1 % Black/African-American, 5.1 % circled multiple ethnicities or “other”; 92.8 % non-Hispanic, 6.2 % Hispanic, 1.0 % left this item blank).

Procedure

After providing verbal informed consent, participants completed questionnaires assessing dispositional mindfulness and were then fitted with electrodes, seated in a comfortable chair in front of a laptop computer, and instructed to rest for a 7-min period during which baseline heart rate (HR) and skin conductance level (SCL) were assessed. After the resting period, participants completed a pre-task measure of negative affect and then performed a stressful laboratory task [Mirror Tracing Persistence Task-Computerized Version (MTPT-C; Strong et al. 2003)] in which they used a computer mouse to trace lines of increasingly difficult geometric shapes presented on a computer monitor. The dot moves in the opposite direction of physical movement, simulating tracing the image in a mirror. Each error—moving the red dot off the shape or a hesitation in movement of 2 s or more—was accompanied by a loud buzzer sound and resulted in having to return to the beginning of the shape. All participants who did not terminate after 5 min working on the final shape were stopped by the experimenter. The participants then completed a post-task negative affect measure. All procedures received IRB approval prior to data collection. The present study includes a re-analysis of data previously presented in Feldman et al. (2014) where study methodology is presented in greater detail.

Measures

Mindfulness was assessed with two questionnaires. The first measure is the CAMS-R (Feldman et al. 2007), a 12-item measure of mindfulness in which respondents are asked to rate how often each statement applies to them on a four-point Likert scale (1 = “rarely/not at all” to 4 = “almost always”) [M = 31.32 (6.20), α = .82). The CAMS-R is scored as a single total score and contains items assessing present-focused attention and awareness as well as items covering accepting attitudes towards inner experience or non-judging, non-avoidance, and non-reactivity as characterized by a recent content analysis of available mindfulness scales (Bergomi et al. 2012). The second measure consists of three facets of the FFMQ (Baer et al. 2006) shown to uniquely predict psychopathology symptoms in previous research (Baer et al. 2006): (a) acting with awareness [eight items, M = 26.12 (5.55), α = .88) measures the tendency to act in a conscious, deliberate, non-automatic manner and to concentrate on present moment experiences, (b) non-judging (eight items, M = 26.20 (6.66), α = .92) measures the tendency to accept one’s thoughts/feelings without judging them as good or bad, and (c) non-reactivity (seven items, M = 20.37 (3.91), α = .76) assesses the tendency to allow thoughts/feelings to enter and pass through awareness without reacting to or becoming absorbed by them. Items are rated on a scale of 1 (“never or very rarely true”) to 5 (“very often or always true”). Higher scores on the CAMS-R and FFMQ facets reflect greater dispositional mindfulness. Both measures have evidence of internal consistency and convergent and discriminant validity (Baer et al. 2006; Feldman et al. 2007) and clinical utility in terms of sensitivity to change and association with symptom improvement in mindfulness-based interventions (Carmody et al. 2009; Greeson et al. 2011). The CAMS-R has been identified among available self-report measures as being particularly relevant to the study of psychological distress (Bergomi et al. 2012), whereas the FFMQ subscales of non-judging and non-reactivity most closely align with the construct of equanimity (Desbordes et al. 2015). The FFMQ acting with awareness scale captures a conceptualization of mindfulness reflected in the MAAS (Brown and Ryan 2003) used in several previous studies of response to laboratory stressors reviewed above (e.g., Arch and Craske, 2010; Brown et al. 2012; Niemiec et al. 2010).

Negative affect (NA) was assessed before and after the stressful task (described in “Procedure” section) with the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS: Watson et al. 1988). The wording of the questionnaire prompt was the same at both time points in that participants were asked to rate their mood state “right now.” As such, the post-task assessment did not ask participants to rate how they felt during the task or about the task itself. NA items assess subjective distress, anger, contempt, guilt, shame, fear, and nervousness. Possible scores on the PANAS range from 10 to 50, and items are rated on a scale of 1 (“very slightly or not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”). A change in NA scores was calculated (post-task score minus pre-task score) as an index of subjective reactivity to the stressful task. The PANAS demonstrated acceptable internal consistency at both pre-task (α = .71) and post-task (α = .81).

HR was measured using a Biopac MP150 system with an ECG100C amplifier and processed with Acqknowledge v3.9 software (Biopac Systems Inc., Santa Barbara, CA). SCL, converted to microsemens (μS), were obtained using the Biopac GSR100C amplifier. Mean HR and SCL were calculated for the 7-min resting baseline period prior to the stressful task and for the duration of the stressful task. HR and SCL reactivity scores were calculated by subtracting mean baseline score from the mean task score.

Data Analyses

The primary analyses of interest consist of four separate hierarchical multiple regression models predicting change in negative affect in response to the laboratory stressor (ΔNA). In the first step of all models, ΔHR was entered. In the second step, one of the four trait mindfulness measures was entered (CAMS-R total score in model 1, FFMQ-Act with Awareness (AWA) in model 2, FFMQ-Non-judging (NJ) in model 3, and FFMQ-Non-reactivity (NR) in model 4). In the third step, the multiplicative interaction of ΔHR and mindfulness score was entered. Next, these analyses were repeated with ΔSCL replacing ΔHR. Cohen’s (1988) guidelines were used for interpreting effect size of R 2 in multiple regression analyses with both a single independent variable (.01 = small, .06 = medium, and .14 = large) and multiple independent variables (.02–.12 = small, .13–.25 = medium, .26 and greater = large). As a follow-up analysis for each multiple regression analysis with a statistically significant interaction term, simple slope analyses were performed following methods described by Preacher et al. (2006) and using their internet-based utility (www.quantpsy.org). Models with a significant interaction term were graphed following procedures described by Aiken and West (1991) for interactions with a moderator that is a continuous variable.

Results

As previously reported in Feldman et al. (2014), the mean change in HR during the stressor task period was not statistically significant (ΔHR M = .66 (4.46), M baseline = 75.65 (10.10), M task = 76.31 (10.27), t(96) = −1.50, p = .14] due to considerable variability in degree of HR reactivity (range −10 to +12), with 41 % of participants exhibiting an overall decrease of at least 1 bpm in HR during the task relative to baseline. Heart rate decelerations have been previously observed in studies using this task in samples of young adults with and without current major depression (Ellis et al. 2013). Also as reported in Feldman et al. (2014), skin conductance increased significantly during the task (ΔSCL M = 2.46 (1.88), M baseline = 2.40 (2.76), M task = 4.87 (3.76), t(96) = −12.88, p < .001), and following the task, significant increases were observed in negative affect (ΔNA = 2.79 (4.46), M baseline = 12.47 (3.00), M task = 15.26 (4.87), t(96) = −6.12, p < .001).

When ΔHR was entered in the first step of each model, it had a significant, positive main effect on ΔNA (small to medium effect) (see Table 1). In the second step, CAMS-R, FFMQ-NJ, and FFMQ-NR each explained additional significant variance in ΔNA in their respective models (small to medium effects), whereas FFMQ-AWA was not a significant predictor in its model. In the final step of the first model, the ΔHR × CAMS-R interaction term was statistically significant, consistent with a moderating effect of mindfulness of thoughts and feelings. Likewise, in the final step of the third model, the ΔHR × FFMQ-NJ interaction term was statistically significant, indicating a moderating effect of the non-judging quality of mindfulness. In the final step of the second model, ΔHR × FFMQ-AWA interaction term approached statistically significance (p = .051), suggesting a possible moderating effect of mindfully acting with awareness. In contrast, in the final step of the fourth model, the ΔHR × FFMQ-NR interaction term was not statistically significant (p = .16). The overall effect size of models 1 (CAMS-R), 3 (FFMQ-NJ), and 4 (FFMQ-NR) were in the medium effect size range, whereas model 2 (AWA) was in the small range.

Simple slope analyses were performed for the two models in which the interaction term was statistically significant (p < .05). In both cases, the predicted relationship between ΔHR and ΔNA was statistically significant only among those scoring 1 SD below the mean on the trait mindfulness measure. Specifically, among those low in mindfulness of thoughts and feelings (−1 SD on the CAMS-R), ΔHR was positively correlated with ΔNA (slope = .45, p = .002), whereas for those high in mindfulness of thoughts and feelings (+1 SD on the CAMS-R), ΔHR was not significantly correlated with ΔNA (slope = .01, p = .96) (see Fig. 1a). Among those low in the non-judging quality of mindfulness (−1 SD on the FFMQ-NJ), ΔHR was positively correlated with ΔNA (slope = .53, p < .001), whereas for those high in the non-judging quality of mindfulness (+1 SD on the FFMQ-NJ), ΔHR was not significantly correlated with ΔNA (slope = −.01, p = .97) (see Fig. 1b).

Moderating effects of mindfulness on the association between change in heart rate (ΔHR) and change in negative affect (ΔNA) to a laboratory stressor. For ease of interpretation, predicted values are presented for HR changes at 1 SD below the sample mean (−4.34 bpm) and 1 SD above the sample mean (+4.34 bpm) and values 1 SD above and below mean scores on mindfulness measured with the CAMS-R (a) and non-judging measured with the FFMQ (b)

When ΔSCL was entered in the first step of each model, it was a marginally significant predictor of ΔNA (small effect) (see Table 2). In the second step, CAMS-R, FFMQ-NJ, and FFMQ-NR each explained additional significant variance in ΔNA in their respective models (medium effect), whereas FFMQ-AWA was not a significant predictor in its model. In the final step of all four models, the ΔSC × mindfulness interaction terms was not statistically significant. The overall effect size of each model was in the small range.

The length of the MTPT-C is not standardized as participants require different amounts of time to complete shapes 1 and 2 and then choose when to terminate shape 3. To determine if this aspect of the stressor introduced a potential confound in measures of stress reactivity, we examined a correlation between total time spent on task with ΔHR, ΔSCL, and ΔNA. As previously reported (Feldman et al. 2014), total time spent on task was significantly associated ΔSCL (r = −.26, p = .009) but not ΔHR (r = −.06, p = .56) and ΔNA (r = −.02, p = .88). When total time spent on the task was entered as a covariate in the eight multiple regression models, the results were unchanged.

Discussion

Hypotheses were supported in that dispositional mindfulness was found to uncouple the association between degree of physiological arousal and subjective distress in the context of a stressful laboratory task. Among less mindful participants, elevated heart rate was accompanied by elevated distress. In contrast, more mindful participants who experienced elevated heart rate did not experience elevated distress. How might mindfulness contribute to subjective-physiological discordance? One possible interpretation is that individuals who are more mindful of their thoughts and feelings and are less judging towards their own inner experience may have demonstrated less emotional reactivity to changes in heart rate experienced in response to the stressful task. Specifically, both the CAMS-R and the FFMQ-Non-judging scale moderated the association of heart rate reactivity and emotional reactivity. What these two measures share are items that capture the tendency to react to internal experience with an attitude of acceptance. It is possible, therefore, that individuals who respond to physiological arousal with a more judgmental attitude may exacerbate the distress they experience. Such an interpretation would be consistent of the concept of experiential avoidance (Hayes et al. 1996) as well as a study that found dispositional mindfulness moderated the association between anxiety sensitivity (fear of the potential negative consequences of anxiety-related symptoms and sensations) and symptoms of self-reported anxious arousal and agoraphobic cognitions (Vujanovic et al. 2007). In contrast, those who are able to allow such experiences and not judge them may be able to “be with” the experience of physical arousal without necessarily being upset by it, consistent with both theoretical models of mindfulness and empirical studies illustrating that mindfulness and acceptance may help to reduce maladaptive reactions to internal experience (Levin et al. 2015). It is important to note that although the assessment of distress in the present study sequentially followed the assessment of physiological arousal, it is not possible to know to what degree the self-reported distress was specifically in response to the physiological arousal or simply the task itself. The interpretation presented above could be strengthened in future studies through an assessment strategy that explicitly assesses participants’ appraisals of physiological arousal during laboratory stressors.

Some limitations and future directions deserve mention. The present findings suggest that the MTPT-C stressor may not have been an ideal task to study concordance of subjective-physiological arousal. The MTPT-C was successful in evoking increased subjective distress and increased SCL across participants; however, there was considerable variability in degree and direction of heart rate reactivity. Many in this sample showed a heart rate decrease, a result consistent with Ellis et al. (2013) who also observed overall heart rate decrease in response to this task in a sample of young adults with and without major depressive disorder. These authors attributed this finding to the focused attention required of the task. The graph of the moderation analyses suggests the key difference in emotional reactivity is between individuals high and low in mindfulness at a high level of increased physiological arousal, whereas differences in emotional reactivity were not evident among those individuals who experienced HR deceleration during the stressful task (see Fig. 1a, b). Nonetheless, an important next step would be to test whether mindfulness moderates physiological-subjective concordance under conditions of more uniform cardiovascular arousal that appear to occur in other laboratory stress tasks (for review, see Gerin 2010). In addition, interpretation of the finding about mindfulness as a moderator of subjective-physiological concordance in heart rate is tempered by the lack of parallel findings in skin conductance measures. This may be attributable to the role of the parasympathetic nervous system in regulating HR but not SC (Diamond and Otter-Henderson, 2007) and it is possible the construct of mindfulness is particularly salient to concordance between subjective distress and physiological reactivity in which there is parasympathetic regulation (Brosschot et al. 2010; Williams and Thayer 2009).

Despite these limitations, the present study adds to the growing literature on the effects of dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness training on both self-reported and physiological reactivity to laboratory stressors. However, it is the first to our knowledge to examine trait mindfulness as a moderator of physiological-subjective concordance, a promising indicator of equanimity in the face of acute stress. Similar analyses could be built into the designs and analysis plans for future laboratory studies and could be readily undertaken in archival data sets in which dispositional mindfulness and physiological and subjective reactivity to a stressor were assessed.

Study 2: Mindfulness and Emotional Reactivity to Daily Lapses in Executive Functioning

Mindfulness training has been found to enhance select laboratory measures of EF (Chiesa et al. 2011; Jha et al. 2010; Teper et al. 2013; Zeidan et al. 2010) as well as self-reported EF (Mitchell et al. 2013). Addressing EF difficulties in the context of mindfulness training may also have important implications for emotional well-being. Self-reported deficits in EF are associated with dysphoric affect and depression symptoms among college students (Bridgett et al. 2013; Feldman et al. 2013; Wingo et al. 2013) and greater depression symptom severity among individuals seeking treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Knouse et al. 2013). The causal direction of the association of EF and depression symptoms reported in these cross-sectional studies is unclear. One recent prospective study in a college student sample found that EF deficits precede the worsening of depression symptoms over a 3-month period, but depression symptoms did not predict worsening EF deficits (Letkiewicz et al. 2014). One goal of the present study was to further test this potential prospective association using a daily diary approach to examine whether daily EF lapses predict end-of-day dysphoric affect. A second objective was to test whether dispositional mindfulness may help to explain why some people experience more or less mood reactivity to daily EF lapses.

Everyday EF lapses such as arriving late for a meeting, forgetting to do something important, or blurting out an inappropriate comment in a social context can give rise to transient negative emotions such as shame, disappointment, or frustration. Some individuals may recover their mood shortly after experiencing the EF lapses; however, some may continue to experience elevated dysphoric mood at the end of the day following EF lapses, a sign of prolonged emotional reactivity to a common, everyday stressor. Lower mood reactivity may be experienced by individuals who are more mindful because they are more present-focused and thus less likely to dwell on this or other past EF lapses or to excessively worry about the future implication of the lapse. In addition, they may be more self-accepting, thus less prone to self-criticism in the face of an EF lapse. They may also be better able to notice that the lapse has occurred but not overanalyze it or become preoccupied with it. The relevance of mindfulness in mood reactivity to EF lapses is suggested by a cross-sectional study that found that the association between the tendency to experience cognitive failures (a concept similar to EF lapses) and depression symptoms was explained in part by dispositional mindfulness (Carriere et al. 2008). However, unlike the present investigation, that study did not directly examine mood reactivity to EF lapses and used a measure of mindfulness (the MAAS) that focuses on attentional/awareness aspects of mindfulness but not non-reactivity and non-judging as captured by the FFMQ and CAMS-R.

We hypothesized that daily EF lapses will be positively associated with daily dysphoric affect. However, this association will be moderated by individual differences in dispositional mindfulness such that individuals who are higher in mindfulness will show a weaker association between EF lapses and dysphoric mood (hence, less mood reactivity) than individuals lower in dispositional mindfulness.

Methods

Participants

Female undergraduates (224) attending a woman’s college in the Northeastern USA who participated in exchange for course credit [age: M = 19.71 (3.02), ethnicity 80.4 % White, 8.9 % Asian or Pacific Islander, 1.8 % Black/African-American, 7.6 % other/mixed heritage, 1.3 % declined; 92.4 % non-Hispanic, 5.4 % Hispanic, 2.2 % declined.)].

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants first completed a series of baseline questionnaires including two measures of dispositional mindfulness (FFMQ and CAMS-R) in a laboratory setting. After completing the laboratory session, each night for seven nights, participants received an email at 7 pm with a link to complete via SurveyMonkey software a nightly questionnaire including measures of end-of-day dysphoric/depressed mood followed by a measure of EF lapses occurring that day. At 10 pm, a follow-up reminder email was sent to all participants who had not yet submitted the nightly questionnaire. Each nightly questionnaire was automatically closed at 2 am to ensure that participants completed the nightly survey on the assigned night. The average number of diaries submitted was 6.7 out of 7, indicating a high rate of compliance. All procedures received IRB approval prior to data collection.

Measures

Mindfulness was assessed with the CAMS-R [M = 31.53 (5.88), α = .83] in a manner similar to study 1. The short form of the FFMQ was used (Bohlmeijer et al. 2011), and the three subscales from study 1 were examined: Act with Awareness [four items, M = 13.84 (2.69), α = .76], Non-judging [five items, M = 16.08 (3.47), α = .76], and Non-reactivity [five items, M = 14.85 (3.38), α = .76].

Dysphoric/depressive affect was assessed with five-item subscale of the PANAS (Watson et al. 1988) including adjectives such as “sad” and “lonely” rated on a 5-point scale in reference to how participants felt “right now” (i.e., at the end of the day when completing the nightly assessment). Across the 7 days, average scores ranged from M = 6.88 (3.03) to 8.28 (3.81) with α ranging from .84 to .92. This measure was also used in another study examining mindfulness as a moderator of the association of daily stress and dysphoric affect (Ciesla et al. 2012).

Executive functioning lapses were assessed with a brief five-item checklist created for the present study by adapting items from the Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale (BDEFS; Barkley, 2012b). EF lapse items consisted of “I procrastinated on an important task,” “I forgot to do an important task.” “I had difficulty motivating myself,” “I was late for something important.” and “I said something to someone that I later regretted.” For each item, participants responded yes or no as to whether they experienced each type of EF lapse during in the past 24 h. Across the 7 days, average scores ranged from M = .87 (1.19) to 1.36 (1.27) with α ranging from .44 to .68. A similar approach was used effectively in a recent study to measure changes in daily EF after a mindfulness-based intervention for ADHD (Mitchell et al. 2013).

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using multilevel modeling procedures as described by Bolger and Laurenceau (2013). A series of four separate analyses were run for each mindfulness variable (model 1a: CAMS-R total, model 2a: FFMQ-AWA, model 3a: FFMQ-NJ, model 4a: FFMQ-NR). Two EF lapse variables were created: Between-subjects (EF-BS, participants average score across 7 days, grand mean centered) and within-subjects (EF-WS, daily deviation from participant’s own between-subjects mean score). The between-subjects variable is largely a covariate that accounts for an individuals’ general tendency to experience/report EF lapses. The within-subjects term is of greater interest as it reflects the unique effect of EF lapses that exceed or fall below a person’s typical daily experience of EF lapses. As such, the primary variables of interest in each analysis are the main effects of mindfulness and EF-WS, and the mindfulness × EF-WS interaction term (presented in the top three rows of Table 3). The following covariates are also included in the equation: the main effect of EF-BS, EF-BS × mindfulness interaction term, and time point in the study (i.e., number of days elapsed since the start of the study). All variables are entered simultaneously in these analyses.

Bolger and Laurenceau (2013) suggest that the analytic approach described above can provide a sufficiently strong test of the causal effect of a daily event (in this case, EF lapse) on an end-of-day psychological state (in this case, dysphoric affect) even if the two variables are assessed at the same time point provided the event temporally precedes the dependent variable. In addition, we performed a more conservative follow-up analysis in which analyses were repeated with an additional covariate added: prior day dysphoric affect (models 1b, 2b, 3b, 4b). In each of these four models, the dependent variable can be conceptualized as change in daily dysphoric affect over the course of the day in which the EF lapse(s) may have occurred. As a follow-up analysis for each multi-level model, simple slope analyses were performed for statistically significant mindfulness × within-subject EF lapse interaction terms following methods described by Bauer and Curran (2005) and using their internet-based utility (www.quantpsy.org). Models with a significant interaction term after controlling for prior day dysphoric affect were graphed following procedures described by Aiken and West (1991) for interactions with a moderator that is a continuous variable.

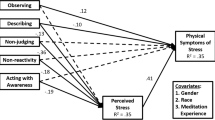

Results

As presented in Table 3, all four mindfulness scales exhibited a significant main effect on daily dysphoric affect in all models, such that higher levels of dispositional mindfulness were associated with lower levels of dysphoric affect. In addition, within-subjects EF lapses exhibited a significant positive association with daily dysphoric affect in seven of eight models. The effect of EF lapses on dysphoric affect was significantly moderated by mindfulness as measured by the CAMS-R (model 1a), the non-judging facet of the FFMQ-NJ (model 3a), and the non-reactivity facet of the FFMQ-NR (model 4a). After controlling for prior day dysphoric affect, only FFMQ-NJ (model 3b) and FFMQ-NR (model 4b) were significant moderators of this association. Simple slope analyses revealed that in the cases of both FFMQ-NJ (model 3b) and FFMQ-NR (model 4b), the predicted relationship between daily EF lapse and dysphoric affect was only statistically significant among those scoring 1 SD below the mean on the mindfulness measure. Specifically, among those low in FFMQ-NJ (−1 SD), EF lapses were positively correlated with dysphoric affect (slope = .59, p < .001), whereas for those high in FFMQ-NJ (+1 SD), EF lapses were not significantly correlated with dysphoric affect (slope = .09, p = .59) (see Fig. 2a). Among those low in FFMQ-NR (−1 SD), EF lapses were positively correlated with dysphoric affect (slope = .57, p < .001), whereas for those high in FFMQ-NR (+1 SD), EF lapses were not significantly correlated with dysphoric affect (slope = .12, p = .45) (see Fig. 2b).

Moderating effects of mindfulness on the association between daily executive functioning lapse and end of day dysphoric affect, controlling for prior day dysphoric affect. For ease of interpretation, predicted values are presented for EF lapses at 1 SD below and above the sample grand mean for within subjects EF lapse scores as well as Non-judging (a) and Non-reactivity (b) scores at 1 SD below and above the sample mean

Discussion

Consistent with hypotheses, participants tended to report greater dysphoric affect at the end of days in which they had experienced more EF lapses than they typically experience. However, non-judging and non-reactivity facets of the FFMQ moderated the effect of these EF lapses on dysphoric affect above and beyond the effect of prior day mood. The present study is the first to our knowledge to establish the role of dispositional mindfulness in moderating the deleterious effect of EF lapses on depressed mood. The use of repeated-measures daily diary methodology also helps to address the limitations of prior cross-sectional studies examining mindfulness as a buffer against emotional reactivity to life events assessed with self-report measures of concurrent hassles (Marks et al. 2010), perceived stress (Bränström et al. 2011), and retrospectively reported childhood adversity (Whitaker et al. 2014). As noted previously, the present study also extends existing literature on reactivity to external events by examining reactivity to EF lapses which may be conceptualized as unwanted internal experience, a category of events that is especially relevant for studying mindfulness as a moderator.

The findings also replicate and extend a prior 7-day diary study by Ciesla et al. (2012) examining mindfulness as a moderator of daily stressful events. Like Ciesla et al. (2012), the moderating effects of non-judging and non-reactivity held after controlling for prior day mood, helping to rule out the possibility that the greater emotional reactivity of less mindful individuals is simply due a tendency to report greater dysphoric affect across study days. Extending the findings of Ciesla et al. (2012), the examination of both within- and between-subjects effects of EF lapses in the present study helps to rule out the possibility that observed reactivity is due to a general tendency of less mindful people to report more EF lapses. In essence, this allows for more definitive evidence that for less mindful individuals, dysphoric affect increases on days in which they experience an increase in EF lapses relative to their own baseline. However, the moderating effects suggest that for more mindful individuals, dysphoric affect remained relatively low even on days characterized by an unusually high degree of EF lapses relative to what they typically experience. In several of the models, the between-subjects EF lapse variable was a significant predictor of daily dysphoric affect above and beyond other predictors in the model. This finding that individuals who generally tend to experience more EF lapses are more likely to experience depressed mood on any given day is consistent with the results of prior cross-sectional studies showing an association between more trait like measures of EF dysfunction and depression symptoms (Bridgett et al. 2013; Feldman et al. 2013; Knouse et al. 2013; Wingo et al. 2013). However, the present study helps to further establish the role of EF lapses in impacting daily variation in dysphoric affect, consistent with recent evidence that EF dysfunction temporally precedes depression symptom development (Letkiewicz et al. 2014).

A limitation that deserves mention is the reliability coefficients for the daily EF lapse measure created for this study fell below the conventional cutoffs. This may be due in part to both the relative brevity of this new measure as well as the binary response format. Refinement of brief EF measures suitable for repeated assessment would be valuable. Furthermore, an important next step for this line of research would be to learn more about the potential intervening cognitive and behavioral mediators of the relationship between EF lapses and dysphoric affect. For instance, it would be useful to test whether more mindful people express more self-compassionate attitudes immediately after experiencing an executive functioning lapse. Self-compassionate mindsets can help to reduce negative affect directly (Leary et al. 2007) and can also enhance intentions to repair damage caused by personal errors and take steps to prevent future lapses (Breines and Chen 2012). A limitation of the present study is that the impact of executive lapses on attitudes towards self and reparative intentions and actions were not assessed. Similarly, reduced daily rumination in response to EF lapses may also be a promising mediator (Ciesla et al. 2012). Direct measurement of such constructs at a daily level could help to further clarify how mindfulness may help people to recover from executive lapses and, as such, could inform the use of mindfulness training in treating disorders characterized by executive functioning deficits.

General Discussion

The present two studies tested whether dispositional mindfulness may play a role in ameliorating two largely understudied forms of stress reactivity: the association of physiological reactivity to a laboratory stressor and subjective reports of emotional arousal (study 1) and the association of EF lapses occurring in daily life and depressed mood at the end of the day (study 2). Across the two studies, greater affective-physiological concordance (study 1) and emotional reactivity to EF lapses (study 2) were observed among individuals who were low in mindfulness. In contrast, individuals higher in mindfulness evidenced an uncoupling, as evidenced by non-significant associations. The novel findings reported in the present studies add to a growing list of studies in which acceptance and mindfulness processes similarly uncouple the expected association between internal experiences and other psychopathological processes spanning a diverse range of problem including emotional difficulties, substance abuse, disordered eating, and self-harm (Levin et al. 2015). The present study also helps to address recent calls to examine the construct of equanimity as an outcome in research on mindfulness (Desbordes et al. 2015) by focusing on emotionally even responding to stressors and examining the time-course of stress response by including repeated measures of emotional distress to assess change following exposure to stressful experiences.

Taken together, the two studies offer evidence of the buffering effects of trait mindfulness across both laboratory and naturalistic stressors. The results also generalize across both broad assessments of negative affective states (study 1) and more focused measures of depressed/dysphoric mood (study 2). In addition, findings were observed across two distinct measures of dispositional mindfulness, the CAMS-R and facets of the FFMQ relevant to the study of negative affective states in non-clinical samples (Baer et al. 2006). Indeed, a strength of the present study is the use of two distinct questionnaires to measure mindfulness, whereas prior laboratory and naturalistic research on emotional reactivity have largely included only a single questionnaire (see Kadziolka et al. (2015) for a recent exception). Despite similar content coverage, the two questionnaires capture somewhat different aspects of dispositional mindfulness. As noted by Bergomi et al. (2013), the CAMS-R may reflect “the willingness and ability to be mindful rather than as a realization of mindfulness experience during the day” which may more closely describe items in the FFMQ. Despite these conceptual differences, results replicated (study 1) and partially replicated (study 2) across both measures.

Examining specific facets of the FFMQ as well as a total mindfulness score (CAMS-R) offered clues about how different aspects of mindfulness may influence emotional reactivity. The non-judging scale buffered subjective-physiological concordance (study 1) and the association of daily EF lapses and increased end-of-day dysphoric affect reactivity (study 2). The non-reactivity facets of the FFMQ predicted greater emotional reactivity following the laboratory stressor (although did not moderate subjective-physiological concordance) and also moderated the effect of daily EF lapses on dysphoric affect above and beyond the effect of prior day mood. The CAMS-R total score, which also contains items assessing non-judging and non-reactivity, moderated subjective-physiological concordance in study 1 and the relationship between EF lapses and emotional reactivity (but not when prior day dysphoric affect was controlled). Taken together, these results generally suggest individuals who take a more accepting attitude of thoughts and feelings in the face of difficult experience and can “let go” of distressing thoughts without dwelling on them appear to be less reactive to a variety of forms of stress.

In contrast, the Act with Awareness scale exhibited only a marginally significant buffering effect on the association of physiological and subjective arousal in study 1 and did not significantly mitigate the effects of daily increases in EF lapse on distress in study 2—the latter replicating the results of a similar daily diary study using the FFMQ (Ciesla et al. 2012). Although this set of findings may suggest that the attentional and awareness aspects of mindfulness may be less relevant to emotional reactivity than acceptance, such an interpretation would be contradicted by a range of studies finding that scores on the MAAS are associated with lower emotional reactivity to a range of stressors (e.g., Arch and Craske, 2010; Brown et al. 2012; Kadziolka et al. 2015; Marks et al. 2010; Niemiec et al. 2010). It may be that because the MAAS assesses mindful attention/awareness (or its absence) in a larger variety of daily contexts than the briefer FFMQ Act with Awareness scale, it is more robust to detect reactivity to a variety of stressors. Although the Act with Awareness facet of the FFMQ did not moderate the effect of daily executive lapses on dysphoric affect, it was a significant moderator of between-subjects mean executive lapses (models 2a and 2b) in the present study. Between-subjects variables are typically covariates not of primary interest in multilevel modeling; however, these results are consistent with two prior studies that found that measures tapping the Act with Awareness facet of mindfulness moderated the stressor-distress association in studies using a single summary score of daily hassles (Marks et al. 2010) and perceived stress (Bränström et al. 2011). It is unclear why the moderating effects of Act with Awareness on the stressor-distress relationship tends to be evident at the level of summary vs. daily measures of stress. Previous research shows that individuals who score low on the MAAS tend to make less benign appraisals of stressors and tend to cope with stressors in less active and more avoidant ways (Weinstein et al. 2009). It is possible that—rather than stressors experienced on a given day being particularly impactful—it is the accumulation of stressors over a period of time that may tax the limited coping skills of people who are less attentive and aware of present-moment experiences.

Taken together, these results may have important implications for the use of MBIs. Broadly, the idea of replacing habitual reactivity to stressors with more intentional and flexible responding is a central aim of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programs, as is an ability to apply “bare attention” in order to directly perceive one’s moment-by-moment experience, uncoupled from more narrative, evaluative processing of these experiences (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). From study 1, the finding that mindfulness may help to de-couple the association of somatic arousal and subjective distress may be particularly relevant in the application of MBIs to anxiety-based conditions such as panic disorder and hypochondriasis where somatic preoccupation and catastrophic interpretations of physical sensations can be a central aspect of psychopathology. Typically, MBIs encourage participants to attend to physiological discomfort with openness, acceptance, and curiosity to reduce emotional reactivity (Roemer and Orsillo 2009). From study 2, the finding that mindfulness may help to de-couple the association of executive-functioning lapses and depressed mood may be particularly relevant for the treatment of disorders such as ADHD and depression where executive functioning lapses may spur self-critical rumination and sustained dysphoric affect. In mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression, judgments about personal short-comings are treated as simply mental events that can be observed dispassionately to help reduce a cascade of further ruminative thoughts and negative affect (Segal et al. 2001) and similar techniques have been adapted for the treatment of ADHD (Mitchell et al. 2014). As such, it would be informative to assess emotional reactivity to physiological arousal and executive functioning lapses before and after participation in MBI to determine if these forms of emotional reactivity are decreased following mindfulness training. To date, neither process has been studied in the growing literature on psychological mechanisms of MBIs (see Chiesa et al. 2014; Gu et al. 2015); however, decoupling effects such as these have been highlighted as both a promising mechanism of action to examine in research on acceptance and mindfulness-based therapies as well as a potentially informative approach to analyzing client self-monitoring assessments in clinical practice (Levin et al. 2015).

In addition to the specific limitations listed in discussion sections for each study, there are limitations that span both studies. First, the use of entirely female samples of college students limits generalizability to men, individuals with more diverse ages and levels of educational attainment, and importantly clinical samples. Nevertheless, the present studies help to elucidate mechanisms of emotional reactivity that may be relevant for a range of psychological disorders that affect younger women and many other demographic subgroups. In addition, it is important to replicate these results among individuals experiencing more severe levels of daily negative affect, physiological arousal, and executive functioning deficits. A further limitation is that information on the participants’ formal practice of mindfulness was not collected. Prior studies conducted with undergraduate students at the institution where the present studies were conducted suggest that regular formal meditation practice in an unselected sample may be relatively rare (e.g., in Feldman et al. 2010, only 4.8 % of participants reported meditating daily). Nonetheless, as popularity and availability of mindfulness training grow, formal mindfulness practice among college student samples is likely becoming more prevalent and thus important to factor into studies of dispositional mindfulness.

Another important limitation that can be addressed in future research is the exclusive focus on emotional reactivity to stressors. Recent theoretical models describe a mindful coping process that may unfold in a temporal sequence (Garland et al. 2011). First, more mindful individuals may be better able to disengage from negative cognitive appraisals of stressful experience, observe these reactions from a more decentered stance, use enhanced attentional resources to view the situation from a broader perspective, and ultimately reappraise the situation in a manner that may further down-regulate negative affect and facilitate constructive coping behavior. The timing and specificity of the assessments in the present study were not sufficient to capture the distinct stages of coping proposed by this model. There is growing evidence from both neuroimaging and other laboratory studies that mindfulness may facilitate a shift to reappraisal following emotional perturbation (see Greeson et al. 2014 for a review). Furthermore, intensive longitudinal studies using repeated assessments throughout the day are a promising approach to capturing how reappraisal and mindful coping responses unfold in response to specific EF lapses, somatic arousal, or other stressful events. Finally, the present study relied on self-reported measures of emotional reactivity and an important recommended future direction is the use of dependent variables capturing equanimity that are not self-reported (Desbordes et al. 2015).

In summary, the present study helps to further establish the relevance of low dispositional mindfulness as a risk factor for emotional reactivity to a variety of stressful experiences and the stress buffering effect of high dispositional mindfulness. Mindfulness-based interventions can increase dispositional mindfulness (Bränström et al. 2010; Carmody et al. 2009; Greeson et al. 2011; Nyklíček and Kuijpers 2008) with recent evidence supporting the notion that cultivating mindful states, over time, fosters more mindful traits (Kiken et al. 2015). Furthermore, daily increase in mindfulness facets occurring during mindfulness training predicts daily improvements in negative affect (Snippe et al. 2015). The present results suggest that the kinds of dispositional qualities cultivated through mindfulness training may help to promote greater equanimity in the face of stress and therefore resilience to a variety of psychological disorders.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Arch, J., & Craske, M. (2010). Laboratory stressors in clinically anxious and non-anxious individuals: the moderating role of mindfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(6), 495–505.

Baer, R. A. (2010). Mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions and processes of change. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness & acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory & practice of change (pp. 1–21). Oakland: New Harbinger.

Baer, R., Smith, G., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

Barkley, R. A. (2012a). Executive functions: What they are, how they work, and why they evolved. New York: Guilford Press.

Barkley, R. A. (2012b). The Barkley deficits in executive functioning scale. New York: Guilford Press.

Bauer, D. J., & Curran, P. J. (2005). Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40, 373–400.

Bergomi, C., Tschacher, W., & Kupper, Z. (2013). The assessment of mindfulness with self-report measures: existing scales and open issues. Mindfulness, 4(3), 191–202.

Bernstein, D. A., Borkovec, T. D., & Coles, M. G. (1986). Assessment of anxiety. In A. Ciminero, K. S. Calhoun, & H. E. Adams (Eds.), Handbook of behavioral assessment (pp. 353–403). New York: Wiley.

Bohlmeijer, E., Klooster, P. M., Fledderus, M., Veehof, M., & Baer, R. (2011). Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment, 18, 308–320.

Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J. P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York: Guilford.

Bolger, N., & Schilling, E. A. (1991). Personality and the problems of everyday life: the role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality, 59(3), 355–386.

Bränström, R., Kvillemo, P., Brandberg, Y., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2010). Self-report mindfulness as a mediator of psychological well-being in a stress reduction intervention for cancer patients—a randomized study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 39(2), 151–161.

Bränström, R., Duncan, L. G., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2011). The association between dispositional mindfulness, psychological well‐being, and perceived health in a Swedish population‐based sample. British Journal of Health Psychology, 16(2), 300–316.

Breines, J. G., & Chen, S. (2012). Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(9), 1133–1143.

Bridgett, D. J., Oddi, K. B., Laake, L. M., Murdock, K. W., & Bachmann, M. N. (2013). Integrating and differentiating aspects of self-regulation: effortful control, executive functioning, and links to negative affectivity. Emotion, 13(1), 47.

Britton, W. B., Shahar, B., Szepsenwol, O., & Jacobs, W. J. (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy improves emotional reactivity to social stress: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 365–380.

Brosschot, J. F., Verkuil, B., & Thayer, J. F. (2010). Conscious and unconscious perseverative cognition: is a large part of prolonged physiological activity due to unconscious stress? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(4), 407–416.

Brown, K., & Ryan, R. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Brown, K. W., Weinstein, N., & Creswell, J. D. (2012). Trait mindfulness modulates neuroendocrine and affective responses to social evaluative threat. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(12), 2037–2041.

Calvo, M. G., & Miguel-Tobal, J. J. (1998). The anxiety response: concordance among components. Motivation and Emotion, 22(3), 211–230.

Carmody, J., Baer, R. A., LB Lykins, E., & Olendzki, N. (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness‐based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 613–626.

Carriere, J. S., Cheyne, J. A., & Smilek, D. (2008). Everyday attention lapses and memory failures: the affective consequences of mindlessness. Consciousness and Cognition, 17(3), 835–847.

Chida, Y., & Hamer, M. (2008). Chronic psychosocial factors and acute physiological responses to laboratory-induced stress in healthy populations: a quantitative review of 30 years of investigations. Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 829.

Chida, Y., & Steptoe, A. (2010). Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status a meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Hypertension, 55(4), 1026–1032.

Chiesa, A., Calati, R., & Serretti, A. (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 449–464.

Chiesa, A., Anselmi, R., & Serretti, A. (2014). Psychological mechanisms of mindfulness-based interventions: what do we know? Holistic Nursing Practice, 28(2), 124–148.

Ciesla, J. A., Reilly, L. C., Dickson, K. S., Emanuel, A. S., & Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Dispositional mindfulness moderates the effects of stress among adolescents: rumination as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(6), 760–770.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Academic.

Coifman, K. G., Bonanno, G. A., Ray, R. D., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Does repressive coping promote resilience? Affective-autonomic response discrepancy during bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 745.

Creswell, J. D., Pacilio, L. E., Lindsay, E. K., & Brown, K. W. (2014). Brief mindfulness meditation training alters psychological and neuroendocrine responses to social evaluative stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 44, 1–12.

Desbordes, G., Gard, T., Hoge, E. A., Hölzel, B. K., Kerr, C., Lazar, S. W., & Vago, D. R. (2015). Moving beyond mindfulness: defining equanimity as an outcome measure in meditation and contemplative research. Mindfulness, 6, 356–372.

Diamond, L., & Otter-Henderson, K. D. (2007). Physiological measures. In R. Robins, C. R. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 370–388). New York: Guilford.

Dorjee, D. (2010). Kinds and dimensions of mindfulness: why it is important to distinguish them. Mindfulness, 1(3), 152–160.

Ellis, A., Vanderlind, W., & Beevers, C. (2013). Enhanced anger reactivity and reduced distress tolerance in major depressive disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(3), 498–509.

Feldman, P. J., Cohen, S., Lepore, S. J., Matthews, K. A., Kamarck, T. W., & Marsland, A. L. (1999). Negative emotions and acute physiological responses to stress. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 21(3), 216–222.

Feldman, G. C., Hayes, A. M., Kumar, S., Greeson, J., & Laurenceau, J.-P. (2007). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: the development and initial validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 177–190.

Feldman, G. C., Greeson, J. G., & Senville, J. (2010). Differential effects of mindful breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and metta meditation on decentering and negative reactions to repetitive thought. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 1002–1011.

Feldman, G., Knouse, L. E., & Robinson, A. (2013). Executive functioning difficulties and depression symptoms: multidimensional assessment, incremental validity, and prospective associations. Journal of Cognitive & Behavioral Psychotherapies, 13(2).

Feldman, G., Dunn, E., Stemke, C., Bell, K., & Greeson, J. (2014). Mindfulness and rumination as predictors of persistence with a distress tolerance task. Personality and Individual Differences, 56, 154–158.

Garland, E. L., Gaylord, S. A., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2011). Positive reappraisal mediates the stress-reductive effects of mindfulness: an upward spiral process. Mindfulness, 2(1), 59–67.

Gerin, W. (2010). Laboratory stress testing methodology. In A. Steptoe (Ed.), Handbook of behavioral medicine: Methods and applications. New York: Springer.

Grabovac, A. D., Lau, M. A., & Willett, B. R. (2011). Mechanisms of mindfulness: a Buddhist psychological model. Mindfulness, 2(3), 154–166.

Greeson, J. M., Webber, D. M., Smoski, M. J., Brantley, J. G., Ekblad, A. G., Suarez, E. C., & Wolever, R. Q. (2011). Changes in spirituality partly explain health-related quality of life outcomes after Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 34, 508–518.

Greeson, J. M., Garland, E., & Black, D. (2014). Mindfulness: A transtherapeutic approach for transdiagnostic mental processes. In A. Ie, C. T. Ngnoumen, & E. J. Langer (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of mindfulness (pp. 533–562). Chichester: Wiley.

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12.

Hayes, A. M., & Feldman, G. C. (2004). Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 255–262.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(6), 1152–1168.

Hoge, E. A., Bui, E., Marques, L., Metcalf, C. A., Morris, L. K., Robinaugh, D. J., & Simon, N. M. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(8), 786–792.

Jha, A. P., Stanley, E. A., & Baime, M. J. (2010). What does mindfulness training strengthen? Working memory capacity as a functional marker of training success. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness & acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change (pp. 207–221). New York: New Harbinger.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living, revised edition: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. Hachette UK.

Kadziolka, M. J., Di Pierdomenico, E. A., & Miller, C. J. (2015). Trait-like mindfulness promotes healthy self-regulation of stress. Mindfulness, 1–10.

Kiken, L. G., Garland, E. L., Bluth, K., Palsson, O. S., & Gaylord, S. A. (2015). From a state to a trait: trajectories of state mindfulness in meditation during intervention predict changes in trait mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 81, 41–46.

Knouse, L. E., Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2013). Does executive functioning (EF) predict depression in clinic-referred adults?: EF tests vs. rating scales. Journal of Affective Disorders, 145(2), 270–275.

Kuyken, W., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., Taylor, R. S., Byford, S., & Dalgleish, T. (2010). How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(11), 1105–1112.

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Allen, A. B., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: the implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 887–904.

Letkiewicz, A. M., Miller, G. A., Crocker, L. D., Warren, S. L., Infantolino, Z. P., Mimnaugh, K. J., & Heller, W. (2014). Executive function deficits in daily life prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(6), 612–620.

Levin, M. E., Luoma, J. B., & Haeger, J. A. (2015). Decoupling as a mechanism of change in mindfulness and acceptance: a literature review. Behavior Modification, 39(6), 870–911.

Lovallo, W. R., & Gerin, W. (2003). Psychophysiological reactivity: mechanisms and pathways to cardiovascular disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(1), 36–45.

Marks, A. D., Sobanski, D. J., & Hine, D. W. (2010). Do dispositional rumination and/or mindfulness moderate the relationship between life hassles and psychological dysfunction in adolescents? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(9), 831–838.

Marx, B. P., Bovin, M. J., Suvak, M. K., Monson, C. M., Sloan, D. M., Fredman, S. J., Humphreys, K. L., Kaloupek, D. G., & Keane, T. M. (2012). Concordance between physiological arousal and subjective distress among Vietnam combat veterans undergoing challenge testing for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25, 416–425.

Mitchell, J. T., McIntyre, E. M., English, J. S., Dennis, M. F., Beckham, J. C., & Kollins, S. H. (2013). A pilot trial of mindfulness meditation training for ADHD in adulthood: Impact on core symptoms, executive functioning, and emotion dysregulation. Journal of Attention Disorders.

Mitchell, J. T., Zylowska, L., & Kollins, S. H. (2014). Mindfulness meditation training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adulthood: current empirical support, treatment overview, and future directions. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22, 172–191.

Niemiec, C. P., Brown, K. W., Kashdan, T. B., Cozzolino, P. J., Breen, W. E., Levesque-Bristol, C., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Being present in the face of existential threat: the role of trait mindfulness in reducing defensive responses to mortality salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(2), 344.

Nyklíček, I., & Kuijpers, K. F. (2008). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on psychological well-being and quality of life: is increased mindfulness indeed the mechanism? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35(3), 331–340.

Nyklíček, I., Mommersteeg, P., Van Beugen, S., Ramakers, C., & Van Boxtel, G. J. (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and physiological activity during acute stress: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology, 32(10), 1110.

O’Neill, S. C., Cohen, L. H., Tolpin, L. H., & Gunthert, K. C. (2004). Affective reactivity to daily interpersonal stressors as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(2), 172–194.

Parrish, B. P., Cohen, L. H., & Laurenceau, J. P. (2011). Prospective relationship between negative affective reactivity to daily stress and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(3), 270–296.

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448.

Roemer, L., & Orsillo, S. M. (2009). Mindfulness and acceptance-based behavioral therapy in practice. New York: Guilford.

Sallis, J. F., Lichstein, K. L., & McGlynn, F. D. (1980). Anxiety response patterns: a comparison of clinical and analogue populations. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 11(3), 179–183.

Segal, Z., Williams, J., & Teasdale, J. (2001). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse (1st ed.). New York: Guilford.

Selye, H. (1974). Stress without distress. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Skinner, T. C., Anstey, C., Baird, S., Foreman, M., Kelly, A., & Magee, C. (2008). Mindfulness and stress reactivity: a preliminary investigation. Spirituality and Health International, 9(4), 241–248.

Snippe, E., Nyklíček, I., Schroevers, M. J., & Bos, E. H. (2015). The temporal order of change in daily mindfulness and affect during mindfulness-based stress reduction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 106.

Steffen, P. R., & Larson, M. J. (2014). A brief mindfulness exercise reduces cardiovascular reactivity during a laboratory stressor paradigm. Mindfulness, 1–9.

Strong, D., Lejuez, C., Daughters, S., Marinello, M., Kahler, C., & Brown, R. (2003). The computerized mirror tracing task. [Unpublished manual].

Teper, R., Segal, Z. V., & Inzlicht, M. (2013). Inside the mindful mind: how mindfulness enhances emotion regulation through improvements in executive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 449–454.

Treiber, F. A., Kamarck, T., Schneiderman, N., Sheffield, D., Kapuku, G., & Taylor, T. (2003). Cardiovascular reactivity and development of preclinical and clinical disease states. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(1), 46–62.

Vago, D. R., & Silbersweig, D. A. (2012). Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): A framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6.

Vujanovic, A. A., Zvolensky, M. J., Bernstein, A., Feldner, M. T., & McLeish, A. C. (2007). A test of the interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity and mindfulness in the prediction of anxious arousal, agoraphobic cognitions, and body vigilance. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(6), 1393–1400.

Watson, D., Clark, L., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Weinstein, N., Brown, K., & Ryan, R. (2009). A multi-method examination of the effects of mindfulness on stress attribution, coping, and emotional well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 374–385.

Whitaker, R. C., Dearth-Wesley, T., Gooze, R. A., Becker, B. D., Gallagher, K. C., & McEwen, B. S. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences, dispositional mindfulness, and adult health. Preventive Medicine, 67, 147–153.

Williams, P. G., & Thayer, J. F. (2009). Executive functioning and health: introduction to the special series. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37(2), 101–105.

Wingo, J., Kalkut, E., Tuminello, E., Asconape, J., & Han, S. (2013). Executive functions, depressive symptoms, and college adjustment in women. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 20(2), 136–144.

Witkiewitz, K., & Bowen, S. (2010). Depression, craving, and substance use following a randomized trial of mindfulness-based relapse prevention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 362.

Zahn, T. P., Nurnberger, J. I., Berrettini, W. H., & Robinson, T. N. (1991). Concordance between anxiety and autonomic nervous system activity in subjects at genetic risk for affective disorder. Psychiatry Research, 36(1), 99–110.