Abstract

Although empirical interest in meditation has flourished in recent years, few studies have addressed possible downsides of meditation practice, particularly in community populations. In-depth interviews were conducted with 30 male meditators in London, UK, recruited using principles of maximum variation sampling, and analysed using a modified constant comparison approach. Having originally set out simply to inquire about the impact of various meditation practices (including but not limited to mindfulness) on men’s wellbeing, we uncovered psychological challenges associated with its practice. While meditation was generally reported to be conducive to wellbeing, substantial difficulties accounted for approximately one quarter of the interview data. Our paper focuses specifically on these issues in order to alert health professionals to potential challenges associated with meditation. Four main problems of increasing severity were uncovered: Meditation was a difficult skill to learn and practise; participants encountered troubling thoughts and feelings which were hard to manage; meditation reportedly exacerbated mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety; and in a few cases, meditation was associated with psychotic episodes. Our paper raises important issues around safeguarding those who practise meditation, both within therapeutic settings and in the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although research interest in meditation has “exploded” in recent years (Brown et al. 2007, p.211), Irving et al. (2009, p.65) suggested that a “striking limitation” of this empirical work was the “absence of research on potentially harmful or negative effects.” (It is worth noting, however, that appreciation of psychological challenges connected to meditation can be found in much of the original source material for meditation, such as early Buddhist texts (Engler 2003). Moreover, scholars are now beginning to focus more efforts on redressing this lacuna (Shonin et al. 2014).) A 2009 review of academic literature on mental health problems connected to meditation identified just 17 relevant primary publications, the majority of which were case studies of problems occurring after participation on intensive retreats (Lustyk et al. 2009). For example, in a multiple case summary, Lazarus (1976) reported incidences of depression among transcendental meditation practitioners, including a suicide attempt by one person following a weekend induction into the practice. However, this study did not discuss the frequency or duration of this practitioner’s meditation practice, nor did it analyse their prior history of suicidal behaviour. Indeed, Perez-de-Albeniz and Holmes (2000) argued that most such case studies did not disentangle the effects of meditation from pre-existing psychological issues. Thus, the few studies that do acknowledge risks around meditation do so usually in terms of it being contraindicated for particular clinical groups, such as those with a history of schizophrenia (Dobkin et al. 2012). There is less understanding of the potential for meditation to trigger problems in people without pre-existing conditions (Lustyk et al. 2009).

Contributing to this lack of understanding is that few studies have explored potential issues around meditation in community populations, i.e., among individuals not identified as specifically at risk of mental health problems, or not meditating as part of a clinical intervention. One exception is Shapiro (1992), who assessed 27 meditators via questionnaire: 62 % reported adverse effects, including depression and anxiety, with 7 % describing more profound issues (e.g., depersonalization). Surprisingly, such findings have not been further investigated. Indeed, amidst the enthusiasm to explore potential benefits of meditation, there is a danger of uncritically portraying it as a panacea for all ills. For example, introducing mindfulness to psychotherapists, Siegel et al. (2009, p.24) suggested that, as a skill, it is a “core perceptual process underlying all effective psychotherapy,” without mentioning the difficulties involved in developing or using this skill. However, buried within almost-uniformly positive presentations of meditation are clues as to potential issues. For example, theorists advise that mindfulness be conducted in a compassionate spirit; otherwise, attention has the potential to have “a cold, critical quality” (Shapiro et al. 2006, p.376). However, the writers did not draw out the negative implication of this statement, i.e. what if practitioners are unable to suffuse attention with compassion? Similarly, MBCT has generally been viewed as contraindicated for those currently depressed because, potentially lacking mental strength to ‘decentre’ from negative cognitions, meditation may draw people further into rumination, potentially worsening their mood (Teasdale et al. 2003). (That said, recent work suggests that MBCT may be used safely and successfully as a treatment for current depression; Manicavasgar et al. 2011) There is, though, little reflection on the consequences should community practitioners be equally incapable of decentring.

The need to investigate the challenges of meditation for community populations is heightened by the fact that such practitioners will often be practising independently (e.g. alone at home), outside the supportive structure of clinical interventions, such as mindfulness-based interventions. Such interventions are increasingly run by trained practitioners with either some clinical training, or affiliated to institutions, such as universities, with ethics protocols in place (Dobkin et al. 2012). Thus, there is liable to be some protection for those practising within these interventions. However, there may be no such safeguards in place for those exploring meditation (in all its varieties) independently. Indeed, while mindfulness has been fairly extensively studied, independent practitioners may encounter more esoteric practices that are less familiar to clinicians and academics, like the Six Element practice (which encourages practitioners to deconstruct the self by focusing on its insubstantiality, in line with Buddhist beliefs). With the exception of pioneering scholars such as Shonin and Van Gordon (2014), such ‘esoteric’ practices have hitherto received little attention in the literature, thus their risks remain largely unknown, further demonstrating the need for research in this area.

Finally, our research is unique in focusing on specifically on men. Male meditators may be particularly vulnerable to problems with meditation because of known issues men have around emotionality. Contemporary gender theorists suggest that men are influenced by dominant cultural norms which can create problems in terms of mental health. For example, toughness norms can mean boys are discouraged from expressing emotion, leading to restrictive emotionality, i.e paucity of emotional recognition and vocabulary (Levant 1992). In turn, restrictive emotionality is thought to contribute to poor emotional regulation (ER) skills, including tendencies to adopt maladaptive coping strategies towards negative thoughts/feelings, e.g. blunting with alcohol (Addis 2008). (ER refers to the processes by which an individual influences how they experience and express emotions (Gross 1999). ER is conceptualized as a cognitive skill with hierarchical features, including lower-level capacities for emotional awareness, and higher-level abilities around modifying emotions.) Moreover, ER deficits are thought to be a transdiagnostic factor underlying diverse mental health issues (Aldao et al. 2010). It is thus conceivable that male meditators may initially lack the ER skills to help them manage negative thoughts/feelings encountered in meditation. (That is not to say that female meditators may not also share such issues; indeed, it is possible that the challenges presented in this paper pertain to meditators more generally, irrespective of gender. Nevertheless, the current study has focused specifically on men; future research could explore similar difficulties in a female population.) However, there have been few studies looking at difficulties around practising meditation and none focusing on men specifically.

Method

Participants

Inclusion criteria were that participants be over 18 years and currently practising meditation, though not as part of a clinical intervention. However, participants were not prevented from participating on the basis of previous engagement with psychiatric or psychological therapy. Indeed, there was no pre-interview screening to assess any such previous engagement, since the study was not focusing specifically on psychopathology, and we also did not anticipate the extent to which data on psychological issues would emerge in a sample of community meditators. In the event, four participants reported having received psychiatric treatment in the past, with three of these first trying meditation as part of a clinical intervention. A further seven men reported undertaking some form of psychological therapy in the past, and five of these first tried meditation on the advice of their therapist. At the time of the interviews, no participants reported currently receiving psychiatric treatment, while three were currently engaging in psychological therapy. (Since participants were not pre-screened for previous engagement with psychiatric or psychological therapy, these numbers were extrapolated from data divulged by participants in the course of the interviews.) There were no restrictions on the types of meditation practised by participants, and a diverse range of practices were covered within the sample. However, most participants were recruited from one particular Buddhist organisation based primarily in the UK, the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO, recently renamed as the Triratna Buddhist Community). Twenty-six of the 30 participants were affiliated to the FWBO in some capacity: Ten were very closely involved with a sangha (i.e. were ordained in the FWBO, and lived and/or worked in an FWBO centre); eleven regularly attended an FWBO centre; and five had only sporadic or occasional involvement. Two participants were affiliated to other traditions (a Hindu meditation tradition, and a group inspired by Thich Nhat Hanh), and two participants were unaffiliated to any movement/tradition. The FWBO teaches two core practices: mindfulness and the metta bhavana (operationalised in the literature as loving-kindness meditation (LKM); Fredrickson et al. 2008). As such, the 26 participants affiliated to the FWBO all practiced both mindfulness and LKM to some extent. Three of the participants unaffiliated to the FWBO were also familiar with these two practices (leaving only the participant who practiced within a particular Hindu tradition, who practiced neither per se). In addition, some participants engaged in other meditation practices; for example, the ten participants ordained in the FWBO had been given advanced meditation practices, such as the Six Element practice.

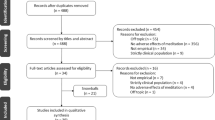

Recruitment was mainly through one FWBO centre, plus other events attended by meditators in London. The project was approved by the University Ethics Research Sub-committee: Protocols were in place to ensure the wellbeing of participants, and recruitment procedures were carefully designed and followed as part of this process. Recruitment was undertaken by the first author, guided by the co-authors, and assisted by gatekeepers at the meditation centre. A purposive maximum variation sampling strategy was used (Marshall 1996), which aimed to include the widest practical range of socio-demographic backgrounds and life experience. Sampling occurred concurrently with, and was influenced by, the emerging data analysis, which suggested the inclusion of certain men to clarify the emerging analysis—such as men not affiliated to a particular meditation group—thus increasing its robustness and credibility (Cutcliffe 2005). A diverse sample of participants was obtained as outlined in Table 1, all of whom lived and/or worked in London, UK.

Procedure

Interviews were semi-structured, undertaken by the first author at a location selected by the participants (their homes or places of work, the meditation centre, or the university). Training in the use of interview techniques was received through the University where the research was conducted; additional guidance was also provided by the co-authors. On average, the first interview (T1) lasted around 2 h, and the follow-up interview (T2) around an hour. Before the T1 interview, participants signed an informed consent form and completed a demographic survey. The project was approved by the University Research Ethics Committee, and an ethics protocol was in place to ensure participants’ wellbeing.

Interviews aimed to elicit narratives concerning men’s experiences of meditation. Narratives order events in time and reflect how people construct and represent meanings about their lives (White 1987). The interview approach was designed to be sensitive to men, providing a safe space for them to tell their own story in their own words (Minichiello et al. 1995). Separate interview guides for T1 and T2 were devised in consultation with the literature and the research team. T1 interviews were in two parts. The first part elicited narratives leading up to engagement with meditation, following up to the present and ahead to the future. The second part focused on topics relevant to the research (if not already discussed), including health and wellbeing, stress and coping. In T2, the first part concerned narratives of the intervening year; the second part focused on the same topics of interest as T1.

Data Analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed. To ensure anonymity, details likely to lead to identification were removed. Transcripts were sent electronically to participants for approval, which all granted. The NVivo software package was used to help organise and analyse the data. The data were explored using a modified constant comparison approach, focusing mainly on open and axial coding (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Modified constant comparison follows the steps of modified grounded theory, including linking back to existing literature to clarify the emerging analysis (Cutcliffe 2005). However, constant comparison falls short of developing a theoretical framework, aiming more to identify and articulate inter-relations between key themes.

The analysis was primarily undertaken by the first author, who again received training in qualitative data analysis from the University, and guidance from the other authors. However, all the authors met and/or communicated at least once per month over the course of 2 years to discuss, debate, refine and verify the ongoing analysis. In an initial coding phase, the first six T1 transcripts were examined line by line to identify emergent themes. Around 80 prominent codes were identified. Subsequent transcripts (from both T1 and T2) were searched paragraph by paragraph for additional codes, with a final figure of 105 codes. This paper concentrates on data pertaining to the challenges associated with practising meditation. (Drawing on the same set of interviews, Lomas et al. (2013a) focused on data pertaining to the reasons men began meditating, and Lomas et al. (2013b) used mixed methods to explore data relating to the development of attention through meditation.) At this juncture, it is worth mentioning that, although qualitative interviews are subject to recall bias (Berney and Blane 1997), the broad-ranging nature of the interviews, the size of the data-set and the existence of these other papers arguably militate against this: Participants were not prompted specifically to recall either positive or negative experiences but rather just to recount a history of their involvement with meditation; that most participants reported both rewarding and adverse episodes suggests that they were relatively free from bias in either direction. Around 20 relevant codes were identified, including ‘encountering negative thoughts,’ and ‘having one’s self-conception challenged.’ The next stage involved the generation of a tentative conceptual framework: Codes were compared with each other and grouped into overarching categories according to conceptual similarity. For example, the two codes above produced a category of ‘troubling experiences of self.’ Other categories included ‘difficulties learning meditation,’ ‘meditation exacerbating problems’ and ‘reality being challenged.’ A final category was ‘compensatory positive experiences.’ These five categories are discussed in turn below. The final stage involved fleshing out the properties, dimensions and interrelations between these codes and categories.

Results

Although there was considerable variation in men’s experiences, in this paper, we focus on common themes to highlight difficulties associated with meditation which may have broader relevance to meditators, and to clinical and psychotherapeutic practitioners using meditation with clients. One overarching theme emerged through our analysis: Although meditation was portrayed on the whole as a rewarding activity, all participants found it challenging at least some of the time, with some men experiencing psychological problems in connection with their practice. (As a percentage, across all the narratives around meditation, problems with it accounted for about one quarter of the data.) Under this broad theme, there were five key themes: difficulties learning meditation; troubling experiences of self; psychological problems being exacerbated; reality being challenged; and compensatory positive experiences. These themes will be discussed below, with interview excerpts in italics. Specific meditation practices will be mentioned as appropriate; mindfulness was the most commonly discussed practice, followed by LKM. However, some themes and excerpts pertained to meditation more generally—many participants did not limit themselves to just one type of practice, but switched between them as appropriate, and so would sometimes speak generally about ‘meditation’—in which case the generic term ‘meditation’ will be used. One final point here: Although the experiences reported below were indeed challenging for participants, many men also emphasised that they often subsequently came to view these experiences as being ultimately valuable for wellbeing and psychological development (e.g. negative experiences of the self being precursors to spiritual insights). As such, many of the themes below are perhaps not so much ‘risks of practice,’ but rather ‘potentially beneficial challenges’ that meditators might ideally be helped to engage with and overcome.

Difficulties Learning Meditation

All men experienced meditation as challenging at various times, with a minority reporting more severe problems. Least serious was that meditation was frequently a difficult skill to learn, associated with varying types of discomfort. Although a few men spoke positively of initial experiences of meditation (Kris: “I thought, ‘I’ve opened the door to something.”), most portrayed early attempts as personally challenging. Reported difficulties—not limited to a particular meditation practice—included physical discomfort (Dustin: “My back was screaming, ‘Stop!’”), self-doubt (Steven: “[I thought], ‘I'm a fake at this.’”) and feeling trapped (Sam: “[I was] screaming, ‘Ring the [final] bell.’”). In relation to mindfulness meditation in particular, participants highlighted their inability to concentrate on inner experience without getting distracted, and described mindfulness as a skill that needed to be constantly practised. However, although narratives contained a development arc—men felt they had improved their meditation skills over time—participants had ongoing struggles with their practice(s). William, an experienced meditator, categorised himself as inattentive: “Meditation is never easy. I almost feel, ‘Why am I doing this? I’m rubbish at it, I just can’t concentrate, there’s too much going on in my head.’”

Aside from the more serious problems detailed below, participants had various lower level complaints about meditation. Men’s lives were often demanding, which impacted on the quality of their meditation (across different types of practice); for example, men wrestled with tiredness or ambivalence (Michael: “I used to force myself to stay awake. [My boyfriend said], ‘This is making you worse rather than better.’”). Meditation could also be dull (Colin: “It can get a bit boring.”) and repetitive (Peter: “It’s like, ‘Here we go again, the same old mind.’”). As such, men could struggle to engage with meditation, sometimes just “[going] through the motions” (Colin), i.e. following the procedures of a practice without being fully involved. Consequently, men sometimes questioned the value of meditating (Andrew: “I [can begin to] doubt, ‘What am I doing, what’s the point.’”). Thus, some suggested that any positive moments in meditation were outweighed by more mundane or arduous experiences.

I’ve had many, many struggles in meditating. … The special moments happened in the context of just plodding along, making mistakes, going down dead ends. That’s what happened most of the time really. (Sam)

Finally, men struggled to integrate mediation into everyday life. Most men stressed the value of daily practice, particularly core practices such as mindfulness and/or LKM (Dean: “A thread you pick up.”). This theme was especially emphasised those who felt meditation had helped them overcome psychological problems, such as depression: Terry initially took up mindfulness “to keep the wolf from the door” i.e., prevent depressive relapse. However, most participants discussed pressures in life that impeded practice, including those who lived and worked full-time in a meditation centre. For example, Michael’s work there had “ratcheted up”—“I haven’t been happy recently, not at all.” Pressures were manifold, including demands from relationships, work and financial concerns, and stress from living in a busy city. Thus, men emphasised the sheer difficulty of sustaining a regular practice.

Work [has been] like skiing down a black run, on one ski, pursued by an avalanche, continuous high levels of hard physical [and] emotional labour. … Meditation is brief [and not] sustaining as it used to be. (Silas)

A Troubled Sense of Self

Beyond these lower-level issues, more troubling experiences were reported, including in relation to common practices such as mindfulness and LKM. Before taking up meditation, many participants had been influenced by societal expectations that men should be tough and had tended to suppress or disconnect from troubling thoughts and feelings (Lomas et al. 2013a). However, men subsequently suffered as a result of this tendency to disconnect. For example, men previously tried to blunt their distress with self-medication strategies (e.g. drinking) that were experienced as maladaptive. Thus, one reason men began meditating was in the hope of coping with distress more effectively. However, deliberately turning inwards and engaging with their inner world, predominantly through taking up the practice of mindfulness, was narrated as a difficult psychological shift. Doing so meant engaging with troubling thoughts, feelings and sensations that men had previously sought to avoid.

You’re coming face to face with your own heart and mind, fear, anger, hatred, confusion, frustration and anxiety, all the difficult emotions. …That’s the whole point. … It was certainly challenging. (Andrew)

It must be emphasised that participants generally understood this engagement with difficult thoughts/feelings not as a flaw or a risk of meditation, but as Andrew put it, the “point” of practice. Indeed, meditation texts throughout the centuries have emphasised this aspect of practice—as did many of the teachers who participants here were taught by—and usually warn and guide practitioners accordingly (Engler 2003). (However, as noted in the introduction, such warnings and guidance may be less visible in academic descriptions of mindfulness and other types of meditation.) Nevertheless, despite participants eventually appreciating the value and importance of engaging with difficult thoughts/feelings in meditation, with mindfulness likened to “turning a light on” (Walter), many men reported being initially surprised, and even shocked, by the thoughts and feelings that were revealed. In terms of thoughts, firstly, men were perturbed by how busy and full their minds seemed, and disturbed by how little control they appeared to have (Andrew: “The thought process happens independent of you. You just think incessant crazy thoughts.”). Men discussed previously assuming that they existed as a free agent, in charge of their thoughts. Observing that this was not necessarily the case could be troubling.

I suddenly got this sense that [all] my life I’d been buffeted around by experience, [and] that I had no control over what I was feeling, or what my conscious mind was doing. (William)

Secondly, many recalled being struck by the negative quality of their thoughts. Men emphasised that, contrary to what they saw as the popular conception of mindfulness, it was not a self-tranquilising “pill to make you feel good.” Rather, Michael called it a “savage” experience, since it “confronts you with yourself. It won’t let you off the hook, it just keeps reflecting you back.” Asked if he found practising painful, he replied, “I found me painful.” Here, men encountered negative thoughts that they were unaware they harboured and which challenged their identities.

[Mindfulness involves] listen[ing] to yourself, and sometimes you don’t like to hear what is coming out. You think “Gosh, my mind is so horrible, I’ve got so much work to do and I don’t know where to start.” (Walter)

There were similar surprises for men in relation to emotions. In light of participants’ previous restrictive emotionality, they described the challenge of trying to become more aware of emotions during mindfulness practice (Dalton: “There’s quite a bit of conditioning to not recognise these things.”). Recognising emotions was portrayed as a learning process, facilitated by techniques such as verbally labelling their emotional experience. As with thoughts, some men were surprised by emotions that were uncovered. In a meditation designed to explicitly cultivate positive feelings for self and others—the metta bhavana, operationalised in the literature as LKM—Dalton was disturbed to uncover negativity towards a close friend (“I couldn’t find any positivity. … I realized how angry I was with him. It was shocking.”). Attempting to explain why he had been caught unawares, he suggested he had never explicitly analysed his feelings towards him (“He’s my mate, you know.”). Other men encountered troubling emotions they had previously disconnected from, exposing buried feelings. During one mindfulness session, Henry was “confronted” with “painful feelings” relating to a childhood trauma he had suppressed for years.

I saw the depth of the pain that is buried. … things that have happened to me that have not been dealt with properly. It can be very scary to know there's that very strong thing in there.

Thus, the narratives point to potential problems around men simply becoming aware of thoughts/feelings without having the skills to deal with them effectively. These problems and the issues they pose are linked to the third main area of concern, considered next.

Exacerbating Psychological Issues

Men focused on three particular issues that could potentially be aggravated by meditation and by mindfulness in particular: poor self-esteem, anxiety and depression. With self-esteem, given the negativity many participants uncovered within, some found that meditation—especially mindfulness—sometimes left them feeling bad about themselves. Theorists define mindfulness as “paying attention … nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience” (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p.145). However, this definition does not reflect the trouble participants had fixing their attention with the desired non-judgmental quality. They suggested that awareness per se could be cold and unforgiving—Silas described it as “a sledgehammer” that he was prone to using for “harsh, critical analysis” of himself. The potential for awareness to highlight men’s flaws appeared to be greater for those who described tendencies towards self-criticism.

Doing mindfulness, you don’t like yourself sometimes. You just become aware, “Actually. I’m a bit of a shit.” If you’ve got a tendency towards negativity, that can make you feel not too good about yourself. … You’re developing awareness of things that set you off down the negative route. You’re opening a can of worms. (Dean)

As elucidated in Lomas et al. (2013b), men gradually cultivated strategies to help them deal with negative thoughts and feelings observed in meditation. For example, through the metta bhavana, men worked on practising compassion for self and others. However, generating self-compassion was an unfamiliar activity for many, and some found it particularly hard to do (Colin: “Initially you can be very harsh on yourself, and your take on meditation tends to be a reflection of what’s going on in your head, being unforgiving on yourself.”). Again, it bears repeating that meditation texts and teachers do emphasise that developing compassion can be difficult—hence the need for and value of specific practices like LKM to assist in this development—and participants eventually came to appreciate the need to practice in this regard. Nevertheless, participants frequently found LKM initially very difficult, and many men continued to have ongoing issues with it. For instance, the practice uncovered emotions that could be hard to deal with: Jimmy was compelled to turn to therapy to help explore the feelings it brought up (“I started thinking of [friends] who had died. I hadn’t let myself get in touch with feelings of grief.”). Some men even avoided LKM as a result of the strong emotions it evoked: “I don’t do it much. It has a strong effect. I find it painful. I experience very strong emotions, and don’t always have the awareness and robustness to deal with those” (Adam).

A second issue associated with meditation was increased sensitivity and anxiety. Many men felt that meditation, particularly mindfulness, had not only made them more sensitive to their inner world, but to the world around them. Some suggested that, before starting meditation, they had been relatively disconnected from their environment. Although men mostly appreciated their enhanced emotional sensitivity, some were troubled by a new-found emotional reactivity. For Ernest, having spent years “disconnecting,” meditation “opened the floodgates:” “I’d be watching an Andrex commercial and I’d burst into tears. I had to readjust. I didn’t know where I was anymore.” Thus, participants’ enhanced sensitivity to the world around them could impact upon them emotionally. As Kris said, “It’s brought up a bit of fear, of violence, of [how] things you take for granted you could lose. …. At work I’m more sensitive to [clients’] distress, I feel their pain.”

Before taking up meditation, internal disconnection from difficult emotions and external disconnection from challenging issues were common strategies that men used in order to cope with a sense of vulnerability. As such, relinquishing an indifferent stance could be difficult. During states of anxiety, mindfulness could make men more sensitive to anxiety-provoking stimuli, thus exacerbating it. For example, although Adam felt mindfulness was fine for lower levels of anxiety, once it escalated beyond a certain threshold, externally directed coping strategies were more suitable than an “introverted” response like meditation. However, this was a lesson learned painfully after initially trying to meditate when anxious, which made things worse.

Getting into deep meditation just made you more sensitive, when actually your whole system would cry out, ‘Stop doing this, it’s mad.’ I needed to do things that took me out of myself. Better to go and see a friend.

Men also spoke about mindfulness being unsuitable for states of low mood—which some self-diagnosed as depression—although again, wisdom about the inappropriacy of meditation was only acquired after difficult meditation attempts. At the second interview, two participants discussed depressive episodes during the previous year (Walter: “Very intense, very painful … scared [by] how dark this absence of light can be.”). Mindfulness was not helpful during these times, as depression had divested them of the strength to manage their negative subjective experience.

I’d feel pain, and [think], “What the hell’s happened to me? I’m a complete wreck.” You can get stuck in that. [I lacked] the energy to turn my mind around. I would just experience suffering, and wasn’t able to do anything with it. (Walter)

Mindfulness thus simply made them aware of their phenomenological distress, without being able to deal with it. Thus, these men gradually and painfully learned that meditation could be not only unhelpful, but counterproductive. Lacking mental strength or agility to decentre, mindfulness could end up just focusing on rumination, exacerbating depression. As such, although participants generally extolled the benefits of engaging with emotions—in contrast to previous tendencies to blunting these—when William was depressed, being “emotionally numb” was a better “way of coping” than meditating. Walter echoed Adam’s advice for anxiety, stressing the importance of externally directed coping strategies for depression: “Don’t meditate! I can’t emphasize that enough. If you don’t have enough light, you get sucked away in the cycle of negative thoughts. It’s very unhelpful.”

The notion of meditation exacerbating, or even generating, mental health issues leads into the fourth, most serious, area of concern, considered next.

Reality Being Challenged

Around half of participants described occasionally undergoing anomalous experiences in meditation. Some of these experiences were highly valued as intensely meaningful and/or pleasurable. For example, in one unspecified meditation, Sam had a “vision” of a “golden and vibrating” sphere “hovering” in his chest: “I felt confident that if I’d manage throughout my life to make a path to reach that source, [then] my spiritual development would unfold naturally.” However, six participants encountered serious difficulties in relation to such episodes, since these anomalous experiences challenged their sense of reality. It must be emphasised that these episodes did not occur in relation to more conventional practices like mindfulness or LKM but, generally speaking, arose under a particular set of circumstances, involving two conditions: (1) attempting advanced meditation practices while still being a relative beginner and (2) doing so without the guidance of an experienced teacher and/or a supportive sangha. For example, Adam described the impact of attempting the Six Element practice, an advanced meditation aimed at deconstructing the self, alone as a beginner. Some experiences arising from this were so “far outside” his “usual experience” as to be “disorienting.” An “out of body” sensation was “alienating and disturbing,” and left him feeling “sick.” Even a blissful experience was “frightening:” Afterwards, he recalled touching objects to reassure himself he was real (“It felt like I’d disappeared into some ethereal sort of realm. I wanted to ground myself.”). Without guidance from a teacher or a sangha to help him interpret his experiences, the deconstruction of the self (which is the goal of the practice) was experienced as a frightening dissolution of identity, rather than as a sense of liberation (which the practice is arguably designed to invoke).

I crashed, lying on the floor sobbing. I had a really strong sense of impermanence without the context, without the positivity. The crushing experience of despair was very strong. … You just feel like you don’t exist, you’re nothing, there’s nothing really there. It’s nihilistic, pretty terrifying.

Whereas Adam’s experiences were disorientating, some men narrated powerful events which were even more debilitating. In response to a “midlife crisis,” in desperation, Harry went alone to an isolated place to search for meaning (“[I was thinking], ‘I have to find what I’m searching for here or die, because I have exhausted every other possibility.’”). Spending a week in (unspecified) contemplative practices, he experienced an “immensely insightful … spiritual awakening.” However, he felt that the insight was so “profound” that his mind was not equipped to handle it (“Like being given an abacus to work out the theory of relativity.”). Having likened his experience to “seeing the tide when it’s in, such stillness, and beauty, and exquisiteness, and oneness,” he discussed the “trauma” of trying to resume normal life.

Coming back into the ‘real world,’ what happens [is] the tide goes out, and what you see is all the rotting prams, the dead dogs, the smells, the sewage. … I asked for it, and I got it, and I have to deal with it. So the last 10 years of my life has been about integrating that, being able to bear the suffering of the world.

Harry felt such experiences were “crazy-making,” saying he felt close to “psychosis” afterwards (“The only reality I knew was to hold onto the doorknob.”). Although he avoided seeking psychiatric treatment, two men had been hospitalised for psychotic episodes (Alan, a number of years prior to the T1 interview, and Alvin, in between T1 and T2 interviews). Although causality cannot be ascertained and psychosis has pre-disposing factors, Alan implicated meditation in a breakdown he suffered the year he began meditating. (In contrast, Alvin attributed his episode to heavy drug use following a relationship break-up.) Alan recalled being “idealistic,” meditating 2 h daily “cut away” in his room, which he felt was the beginning of the “alienation process.” Although Alan did not specify the practices he was undertaking during this time, he described fixating on “extreme notions” relating to Buddhism, like imagining how reincarnation in “hell realms” would feel. In retrospect, he felt he became “egotistical” through meditation (“Dwelling on my own thoughts, thinking I was the centre of the universe, and was going to be the next Buddha.”), which he believed had contributed his breakdown.

I sat on the pavement and tried to meditate. I got picked up by the police. … I went from bad to worse. I wanted to kill myself and tried to throw myself out the window. I got given drugs, a high dosage. I was violent.

In reflecting on such experiences, these men argued that meditation needed to be treated with respect. Adam likened meditation to a “power-tool” which can be “dangerous” and must be “used appropriately.” They emphasised the importance of a supportive context to ensure that practices are learned properly and to help manage powerful experiences that can occur. Although Alvin had not resumed meditation by the time of the T2 interview, Alan had re-engaged with a practice some years ago, tentatively meditating approximately 2 years after his discharge from hospital. However, he was now more wary about the risks of meditation and had learned to be more careful in his practices, and to seek out appropriate support and guidance from experienced teachers: “Meditation is great, [but] if you’re not skilled, or don’t get the right guidance, which I wasn’t getting, it can go down a slippery path. You have to be cautious.”

As Alan’s excerpt indicates, despite the multitude of potential issues, ultimately, men valued meditation, with manifold positive effects which compensated for troubles encountered.

Compensatory Positive Experiences

Participants contextualised the difficulties above by emphasising that, on the whole, meditation contributed to wellbeing, in two key respects: equipping them with coping skills and generating positive experiences. First, although men encountered negative thoughts and feelings in meditation, through meditation, they also gradually acquired emotional management strategies and “tools” to help deal with these, as outlined in Lomas et al. (2013b). Moreover, men found that meditation could give rise to subjective wellbeing. In relation to mindfulness, men often used the word “stillness” to describe the mental state that they sometimes accessed in this practice, in contrast to the agitation they were more used to. Dean depicted the mind as water with “the surface all churned up;” in meditation, you could get “underneath all the churning” and “the deeper you get, the stiller it gets.” Walter suggested that if mindfulness went well, the mind “slowed down” and even had “no thought for a while.” In articulating this stillness, men used the word “happiness” but qualified this with revealing adjectives like “more refined” (Adam), “softer” (Ross) and “more pure” (Dean). Men also used “fulfillment” (Dalton), “contentment” (Ross) and “wholeness” (Silas) to depict this state, suggesting it was different to anything experienced in ‘outside life’ (William: “Everything is all right as it is, and there’s nothing to grasp for. … That form of happiness is quite rare.”). Going further, some men recalled intense positive emotions linked to meditation (across a range of different practices): Alan described an experience of “rapture”—not in a meditation practice per se, but after just taking up unspecified meditation practices—which he explained as “the natural corollary” of the “joyfulness” he had been feeling:

The sun was streaming through, the light was clear. My hair was standing up on end. Then from inside, a wave of ecstasy, just a complete feeling of love and warmth and more than joy.

Discussion

The current paper is unusual in providing analysis of the manifold challenges and even psychological problems related to meditation (an overarching term for a diverse range of practices). Although we set out to explore the impact of meditation upon men’s wellbeing (anticipating that this impact would be positive), as some men have issues with emotionality, in retrospect, it is understandable that narratives about struggling with meditation emerged in our sample. Our analysis is timely, since few studies have explored the downsides of meditation (Lustyk et al. 2009), particularly among those who might be called grey meditators, i.e. practising in the community, largely independently of monitored interventions. Our findings uncovered multiple psychological issues, hitherto less-reported or sidelined, which show meditation as a potent activity that practitioners would do well to respect as such. The findings around psychological issues are all the more notable given that we had not set out to recruit people who had undergone difficulties with meditation, just men who actively practised it. The fact that nearly all reported particularly challenging experiences with meditation—some very serious—is thus all the more striking. We must repeat the point that meditation texts and teachers generally emphasise that such experiences are not necessarily a reflection of meditation going wrong or having no value; on the contrary, scholars recognise that meditation is fundamentally about engaging with difficult thoughts/emotions (Engler 2003). Nevertheless, it remains the case that participants here often found these experiences challenging to deal with, especially at first. Moreover, while such difficulties may be acknowledged and dealt with by meditation texts and teachers, these issues have tended to be somewhat overlooked by the academic literature on meditation generally (and mindfulness specifically), hence the need for and value of the present article.

One useful theoretical framework for understanding the findings reported above is emotion regulation (ER), i.e the processes by which an individual influences how they experience and express emotions, including paying attention to and processing emotions (Gross 1999). In a theoretical review, Chambers et al. (2009) suggested that meditation—mindfulness in particular—contributes to wellbeing by encouraging “mindful emotion regulation” in practitioners, including the ability to decentre in the face of “disturbing emotions.” However, Chambers et al. admitted that decentring is “conceptually simple but very difficult to achieve” (p.568). Indeed, our results highlight—for the first time in a detailed way, using narrative accounts—the difficulties involved in trying to decentre and in becoming skilled at meditation generally. Moreover, our study is unique in exploring the difficulties of developing ER in the context of gender. It is thought that traditional masculine norms (e.g. toughness) can lead to restrictive emotionality in men (Levant 1992), which in turn contributes to ER deficits (Addis 2008). In the current study, although meditation did appear to develop men’s emotional management skills (Lomas et al. 2013b), this was a challenging process. Having previously been encouraged by masculine norms to disconnect from negative emotions, turning towards this inner experience in meditation could thus be troubling. One particular problem appeared to be that men became aware of emotions (a lower-level skill) before they had the ability to modify these (a higher-level skill). That is, men uncovered negative or painful subjective content but were usually not yet sufficiently skilled to manage such content adeptly. Given tendencies towards ER deficiencies among men generally, a lack of skills required to moderate troubling content may turn out to be a particular challenge for male meditators. (However, we are not claiming that such difficulties are peculiar to men, or even just more prevalent among men, but rather that our data only reflect the experiences of male meditators. It may be the case that these are generic issues with meditation: Further research with both men and women will be needed to better understand any such gender differences in this area.)

In finding that meditation can be experienced as unpleasant or troubling at times, our results corroborate those of Kerr et al. (2011). However, the problems reported in the present study seemed to be rather more serious, as the negative content encountered in meditation was sometimes associated with various psychological problems. First, such content challenged men’s self-identity, sometimes to the detriment of self-esteem. Moreover, although participants tried to cultivate qualities to manage this negative content (e.g. loving kindness), some found this difficult. Again, while meditation texts acknowledge the difficulty of developing qualities such as loving-kindness, it is important to highlight this issue in an academic paper on the subject. This finding suggests that men may need specific assistance in cultivating self-compassion, which has implications for compassion-focused psychological interventions for mental health (e.g. Gilbert 2009). Meditation also exacerbated depression in some cases. Mindfulness is generally recognised as inappropriate for current depression in the literature (Teasdale et al. 2003) (although some emergent studies have challenged this blanket proscription; e.g. Manicavasgar et al. 2011). Narratives here support Teasdale et al.’s explanation as to why meditation is ill-advised: lacking strength to decentre as they normally would, men were drawn into a spiral of depressogenic thinking. However, results here are notable in highlighting potential dangers of meditation in a community population, and more specifically, in suggesting that ER deficits in men may possibly make them more susceptible to this risk (future research would need to investigate this suggestion further). In addition, our study indicates that meditation can increase sensitivity and associated anxiety, which is generally overlooked in the literature.

More seriously, certain meditation practices—particularly advanced ones such as the Six Element practice—were linked by some participants to severe effects, including reality-testing and depersonalisation. The question of whether depersonalisation is a desired state of mind in meditation is a complex issue, one further complicated by semantics around the concept of the self and whether one should aim to 'lose' this (Engler 2003). Among participants here, some spoke in positive terms about “overcoming” or “surpassing” the self. However, depersonalisation was discussed in highly negative terms by six men here, which at around a fifth of the sample is higher than the 7 % describing similar serious issues in Shapiro (1992). Moreover, one man linked his adverse experiences to subsequent states of psychosis (another man came ‘close to’ psychosis following intense experiences in meditation, while a third man experienced psychosis, but did not connect it to meditation specifically). While meditation has generally been contraindicated for those at risk of psychosis (Lustyk et al. 2009)—although other work has suggested that mindfulness can be helpful in treating this (e.g. Chadwick et al. 2005)—there is little research on the potential for meditation to precipitate or exacerbate psychotic episodes in the general population (Dobkin et al. 2012). The few studies connecting meditation to adverse psychological effects have been case studies which were generally unable to adduce causality (Perez-de-Albeniz and Holmes 2000). Although causality cannot be ascertained in this study either, men’s narratives clearly made the link: Five of the six men here mentioned no mental health problems prior to starting meditation, and four believed their adverse experiences were directly linked to their practice. Lustyk et al. suggest that one reason meditation may induce states of psychosis is because depersonalisation is linked to sensory deprivation, which can occur in meditation. There is some support for this argument in the narratives here (e.g. in Alan’s account). In the context of the discussion above, it may also be relevant that affect dysregulation is also considered a contributing factor to psychotic experiences (Van Rossum et al. 2011). However, it is also recognised that psychotic content can be reflective of a person’s cultural context (Whaley and Hall 2009), thus these psychotic experiences may have been shaped by men’s interest in meditation, rather than caused by it. Also, it must be noted that mindfulness has successfully been used in the treatment of psychosis, featuring specific modifications appropriate to the condition (Chadwick et al. 2005).

Moreover, it is important to strike a note of balance. Despite difficult experiences, all men generally viewed meditation positively, even those who had suffered psychosis: They felt that their problems had been due to meditating incorrectly and/or to a lack of guidance in interpreting anomalous experiences. In particular, severe adverse experiences were generally associated with a combination of (1) attempting advanced meditation practices (such as the Six Element practice) while still a relative beginner and (2) lacking a teacher or a sangha to help one make sense of these experiences. Furthermore, some men even attributed significance to their adverse experiences, supporting the notion of post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004). Moreover, most men reported compensatory experiences of subjective wellbeing (SWB) which sustained their interest in meditation, despite its issues. Similar links between meditation, especially mindfulness, and SWB have been found in experimental (Shapiro et al. 2007) and qualitative research (Matchim et al. 2008). However, our study is unusual both in suggesting that, for this particular group of male meditators at least, experiences of SWB in meditation may be more infrequent than many people believe, but also that such positive experiences can be particularly potent. Contrary to depictions of mindfulness, and meditation generally, as a relaxing process of self-tranquilisation (Friedman et al. 2001), so-called mental stillness, frequently portrayed as characterising the meditative state in the literature (Zahourek 1998), was achieved neither frequently nor easily. (Again though, this finding may be a function of the specific types of practice undertaken by these participants and cannot be generalised to other forms of practice not reported on here, such as transcendental meditation.) However, men did recall states of contentment which, although rare, were highlights of their life. Here, men’s experiences challenged a distinction in the literature between SWB and Psychological Wellbeing (e.g. having meaning in life) (Ryan and Deci 2001), since the most pleasurable experiences in men’s lives were sometimes also the most meaningful.

However, despite this positive note, that nearly all men reported that meditation had affected them adversely at certain points—sometimes seriously so—means caution is warranted in recommending it for the treatment of mental health issues and for the promotion of wellbeing generally. This caution is important, as there is considerable enthusiasm for using meditation as a clinical tool—among clinicians, clients, and in society more generally—an enthusiasm fuelled by the largely positive academic literature on the topic. For example, the Mental Health Foundation (2010, p.4) suggested that mindfulness has a “much wider application” than just treating depression, calling for “this potentially life-changing approach to be more readily available.” Although Lustyk et al. (2009) advised that clinicians conduct cost–benefit analyses before conducting interventions, including screening (e.g. for historic psychiatric problems), the present study highlights the risks of meditation in community populations. By encouraging introspection, meditation generally (and mindfulness specifically) has parallels with counselling and psychotherapy; however, these latter interventions are designed around interaction with a professional who can guide clients to work constructively with negative emergent content (Bergin and Garfield 1994). In contrast, no such provisions may necessarily be in place with meditation—especially for those practising independently—and although meditators may turn to teachers and fellow practitioners for support, there is not necessarily a safety net to ensure they do so.

Recommendations and Limitations

On the basis of our findings, a number of recommendations can be made concerning the teaching of meditation; thus, the following points are for practitioners seeking to utilise meditation in their clinical, counselling or psychotherapeutic practice. (These are generic guidelines, designed to be applicable across all forms of meditation. The design of the current study does not permit us to make recommendations about specific forms of meditation practice, such as mindfulness. Future research will be needed to provide further guidelines specific to particular practices.) First, meditation exercises focusing on thoughts or emotions may be inadvisable for clients in a state of anxiety or low mood; exercises focusing on physical sensations such as breathing may be more appropriate, since these are less likely to result in a practitioner becoming immersed in their negative thoughts/feelings. (This recommendation was actually suggested by a number of participants in the course of their interviews.) Second, meditation can sometimes bring people into contact with troubling thoughts and feelings that can be difficult to manage; clients may need to be supported after the meditation session in working through these. Third, men may have particular difficulties with meditation on account of prior tendencies towards restrictive emotionality; men may need special assistance in recognising emotions and cultivating qualities like self-compassion. (That said, women are also liable to experience difficulties around self-compassion, although this may manifest in different ways according to gender-related social pressures. For example, Wasylkiw et al. (2012) suggest that women may face particular issues around self-compassion in relation to issues such as body image and weight.) Finally, practitioners who advise clients to try meditation in the community should do so with caution, as clients may encounter difficulties in their practice but lack the therapeutic support at the time to help them manage these.

Relating to this last point, our paper also offers recommendations for teachers and meditation centres in the community. It would be advisable for such centres/teachers to have the following protocols in place. First, screening participants in terms of present mental state, with a wider remit than psychiatric history. For instance, monitoring the current mood of practitioners is an important safeguard (indeed one that was followed in the ethics protocol for the research interviews analysed in this paper, as were the third and fourth recommendations listed below). Second, those judged to be at risk (e.g. in a state of anxiety) are advised to try meditation only under the guidance of a qualified clinical, counselling or psychotherapeutic practitioner, or at a minimum be carefully monitored by the session leader. Third, all participants should be informed of potential risks and be given opportunities to withdraw. Fourth, session leaders should make provisions for spending time after the session with any participants who wish to discuss concerns, or at the very least have information for clinical, counselling or psychotherapeutic services to hand for anyone who appears to have been particularly troubled by the practice. (Ideally both provisions would be in place.) Finally, such centres are strongly advised to emphasise to practitioners the potential psychological risks of attempting advanced meditation practices without guidance from an experienced teacher and the support of a sangha.

Limitations of the research mean caution is needed in generalising the findings. For example, despite an objective of maximum variation sampling, the men recruited cannot be considered to be representative of the general population. For example, the sample featured a relatively high proportion of gay men (nine out of 30). (Gay men were not specifically recruited; this just happened to be the nature of the sample. Participants themselves explained the relatively high number of gay people within Buddhism as due to it being less homophobic and more inclusive than other religions, as others have also reported (Schalow 1992).) The censure of homosexuality in society as a marginalised form of masculinity has been linked to higher rates of mental illness among gay people (Mills et al. 2004). Thus, it is possible that gay meditators—and heterosexuals who display qualities seen as feminine, which are also policed by the same censure (Schippers 2007)—were particularly susceptible to psychological issues, which meditation subsequently uncovered. (That said, none of the issues reported here were exclusive to homosexual participants, and so do also potentially apply to heterosexual meditators.) The sample is likely to not even be representative of the population of those who have tried meditation, since the self-selecting inclusion criteria meant that only men who currently practise meditation, and were willing to talk about it, were included in the study. However, this point makes the findings all the more notable. That is, the negative issues detailed above were provided by men who felt sufficiently enthusiastic about meditation to have maintained their practice. Thus, the sample arguably excludes people whose experiences of meditation were so troubling as to cause them to cease practising (since only currently active meditators were recruited). It may be of future interest to interview ex-meditators, as they may provide other insights into the potential for harm. (That said, looked at more positively, the analysis here may also potentially be over-reporting possible issues with meditation practice, since the sample also excludes other hypothetical categories of practitioners, such as those who have found meditation to be so successful that they have ceased to need to practice it.) Moreover, participants here were mainly recruited from just one meditation centre: Scholars are beginning to understand the extent to which meditation experience is shaped by the philosophy and pedagogy of the particular teaching context (Obadia 2008); as such, it is possible that the problems uncovered in this paper were a function of the particular context in which these participants practised. Finally, it is important to remind readers that all participants in this study deemed meditation to be a valuable activity, one conducive to mental wellbeing. However, that should not occlude us to the fact that it can also be potent activity—in both a positive and a negative sense—and may need to be practiced with guidance.

References

Addis, M. A. (2008). Gender and depression in men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15(3), 153–168. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00125.x.

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004.

Bergin, A. E., & Garfield, S. L. (1994). Handbook of psychotherapy and behaviour change (4th ed.). Oxford: John Wiley and Sons.

Berney, L. R., & Blane, D. B. (1997). Collecting retrospective data: Accuracy of recall after 50 years judged against historical records. Social Science & Medicine, 45(10), 1519–1525.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237.

Chadwick, P., Taylor, K. N., & Abba, N. (2005). Mindfulness groups for people with psychosis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33(3), 351–359. doi:10.1017/S1352465805002158.

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005.

Cutcliffe, J. R. (2005). Adapt or adopt: Developing and transgressing the methodological boundaries of grounded theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 51(4), 421–428. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03514.x.

Dobkin, P., Irving, J., & Amar, S. (2012). For whom may participation in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program be contraindicated? Mindfulness, 3(1), 44–50. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0079-9.

Engler, J. (2003). Being somebody and being nobody: A reexamination of the understanding of self in psychoanalysis and Buddhism. In J. D. Safran (Ed.), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An unfolding dialogue (pp. 35–79). Somerville: Wisdom Publications.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062. doi:10.1037/a0013262.

Friedman, R., Myers, P., & Benson, H. (2001). Meditation and the relaxation response. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Assessment and therapy (pp. 227–234). San Diego: Academic Press.

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15, 199–208. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.107.005.264.

Gross, J. J. (1999). Emotion regulation: Past, present, future. Cognition and Emotion, 13(5), 551–573. doi:10.1080/026999399379186.

Irving, J. A., Dobkin, P. L., & Park, J. (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health professionals: A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 15, 61–66. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.01.002.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg016.

Kerr, C. E., Josyula, K., & Littenberg, R. (2011). Developing an observing attitude: An analysis of meditation diaries in an MBSR clinical trial. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(1), 80–93. doi:10.1002/cpp.700.

Lazarus, A. A. (1976). Psychiatric problems precipitated by transcendental meditation. Psychological Reports, 39(2), 601–602.

Levant, R. F. (1992). Toward the reconstruction of masculinity. Journal of Family Psychology, 5, 379–402. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.5.3-4.379.

Lomas, T., Cartwright, T., Edginton, T., & Ridge, D. (2013a). ‘I was so done in that I just recognized it very plainly, “You need to do something”’: Men’s narratives of struggle, distress and turning to meditation. Health, 17(2), 191–208. doi:10.1177/1363459312451178.

Lomas, T., Edginton, T., Cartwright, T., & Ridge, D. (2013b). Men developing emotional intelligence through meditation? Combining narrative, cognitive, and electroencephalography (EEG) evidence. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. doi:10.1037/a0032191.

Lustyk, M. K., Chawla, N., Nolan, R. S., & Marlatt, G. A. (2009). Mindfulness meditation research: Issues of participant screening, safety procedures, and researcher training. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine, 24(1), 20–30.

Manicavasgar, V., Parker, G., & Perich, T. (2011). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behaviour therapy as a treatment for non-melancholic depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(1–2), 138–144. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.027.

Marshall, M. (1996). Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice, 13(6), 522–525. doi:10.1093/fampra/13.6.522.

Matchim, Y., Armer, J. M., & Stewart, B. R. (2008). A qualitative study of participants’ perceptions of the effect of mindfulness meditation practice on self-care and overall well-being. Self-Care, Dependent-Care and Nursing, 16(2), 46–53.

Mental Health Foundation. (2010). Mindfulness report. Retrieved from http://www.livingmindfully.co.uk/downloads/Mindfulness_Report.pdf.

Mills, T. C., Paul, J., Stall, R., Pollack, L., Canchola, J., Chang, Y. L., & Catania, J. A. (2004). Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(2), 278–285. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278.

Minichiello, V., Aroni, R., Timewell, E., & Alexander, L. (1995). In-depth interviewing: Principles, techniques, analysis. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Obadia, L. (2008). The economies of health in Western Buddhism: A case study of a Tibetan Buddhist group in France. In D. C. Wood (Ed.), The economics of health and wellness: Anthropological perspectives (pp. 227–259). Oxford: JAI Press.

Perez-de-Albeniz, A., & Holmes, J. (2000). Meditation: Concepts, effects and uses in therapy. International Journal of Psychotherapy, 5(1), 49–59. doi:10.1080/13569080050020263.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141.

Schalow, P. G. (1992). Kukai and the tradition of male love in Japanese Buddhism. In J. I. Cabezón (Ed.), Buddhism, sexuality and gender (pp. 215–230). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Schippers, M. (2007). Recovering the feminine other: Masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony. Theory and Society, 36(1), 85–102.

Shapiro, D. H. (1992). Adverse effects of meditation: A preliminary investigation of long-term meditators. International Journal of Psychosomatics, 39, 62–67.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–390. doi:10.1002/jclp.20237.

Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., & Biegel, G. M. (2007). Teaching self-care to caregivers: Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1(2), 105–115. doi:10.1037/1931-3918.1.2.105.

Shonin, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2014). Mindfulness of death. Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0290-6.

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Do mindfulness-based therapies have a role in the treatment of psychosis? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(2), 124–127.

Siegel, R. D., Germer, C. K., & Olendzki, A. (2009). Mindfulness: What is it? Where did it come from? In F. Didonna (Ed.), Clinical handbook of mindfulness (pp. 17–35). New York: Springer.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, S. V., & Williams, J. M. G. (2003). Mindfulness training and problem formulation. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 157–160.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry: An International Journal for the Advancement of Psychological Theory, 5(1), 1–18. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01.

Van Rossum, I., Dominguez, M., Lieb, R., Wittchen, H.-R., & Van Os, J. (2011). Affective dysregulation and reality distortion: A 10-year prospective study of their association and clinical relevance. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(3), 561–571. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp101.

Wasylkiw, L., MacKinnon, A. L., & MacLellan, A. M. (2012). Exploring the link between self-compassion and body image in university women. Body Image, 9(2), 236–245.

Whaley, A. L., & Hall, B. N. (2009). Cultural themes in the psychotic symptoms of African American psychiatric patients. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(1), 75–80. doi:10.1037/a0011493.

White, H. (1987). The content of the form: Narrative discourse and historical representation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Zahourek, R. P. (1998). Intentionality in transpersonal healing: Research and caregiver perspectives. Complementary Health Practice Review, 4(1), 11–27. doi:10.1177/153321019800400104.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lomas, T., Cartwright, T., Edginton, T. et al. A Qualitative Analysis of Experiential Challenges Associated with Meditation Practice. Mindfulness 6, 848–860 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0329-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0329-8