Abstract

Recently, there has been a call for additional research on third-wave parenting interventions incorporating mindfulness and acceptance. A third-wave approach to parenting intervention may be particularly relevant to parents of children with disabilities. This paper provides a systematic review of the existing literature on third-wave parenting interventions for parents of children with disabilities, examining parental and/or child adjustment as an outcome. Four papers were identified and all studies were pre–post designs. The existing literature is promising; however, randomised controlled trials are needed. The importance of extending third-wave parenting interventions to parents of children with disabilities is discussed, and recommendations are made for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The ‘third wave’ of cognitive behavioural intervention refers to a paradigm shift characterised by the inclusion of mindfulness and acceptance (Hayes 2004). Third-wave interventions include Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Kostanski and Hassed 2008). All third-wave interventions include mindfulness—deliberate nonjudgmental attention to moment-to-moment experience—or acceptance—ongoing nonjudgmental contact with psychological events. In addition, the third-wave emphasises the function and context of behaviours and cognitions rather than the form. Mindfulness and acceptance may be explicitly taught and practiced through mindfulness exercises such as mindfulness of the breath or mindfulness of walking (as in MBSR), or it may be fostered in other ways, such as exercises that decrease the dominance of language (as in ACT).

Recently, there has been a call to extend the third wave to parents by enhancing existing behavioural parenting interventions with mindfulness and investigating the effects of mindfulness-based interventions on parental adjustment and parenting (Cohen and Semple 2010; Dumas 2005; Duncan et al. 2009; Greco and Eifert 2004). A third-wave approach to parenting intervention may enhance existing interventions by addressing the psychological function of parenting practices for the parent (Coyne and Wilson 2004) and parenting behaviour that has become automatic (Dumas 2005). For example, maladaptive parenting practices may be maintained not because of parental skill deficits, but because they have a psychological function for the parent of avoiding painful psychological content or they have become automatic and resistant to contextual contingencies. Increasing the parent’s ability to keep ongoing nonjudgmental contact with psychological events may produce more flexible parenting behaviour. In addition, a third-wave approach to parenting intervention may enable behavioural parenting interventions to more effectively address research on emotional regulation, the parent–child relationship and attachment (Cohen and Semple 2010; Duncan et al. 2009; Gottman et al. 1996). For example, parents who are open, aware and accepting of emotion may be better able to support their child in understanding their own emotions through validation, verbal labelling of emotions and problem solving. This parental approach to emotion, which is consistent with the third wave, has been shown to improve the quality of parent–child relationships and the emotional regulation abilities of the child (Gottman et al. 1996).

Extending the third wave to parents of children with disabilities may be particularly fruitful. Parents of children with disabilities experience additional challenges such as increased burden of care (Sawyer et al. 2011) and grief (Eakes et al. 1998; Whittingham et al. 2013) and greater parental stress (Gupta 2007; Rentinck et al. 2007), and they are more likely to experience anxious and depressive symptoms (Barlow et al. 2006; Lach et al. 2009). Further, children with disabilities are more likely to have behavioural and emotional problems (Brereton et al. 2006; Carlsson et al. 2008; Einfeld and Tonge 1996; Parkes et al. 2009; Parkes et al. 2008). A third-wave approach may prove useful in supporting parents of children with disabilities by improving parental psychological adjustment, supporting parents’ grieving experiences, encouraging flexible parenting and promoting parenting practices that optimise children’s socioemotional development.

The primary objective is to systematically review the existing literature to ascertain the current state of the evidence for a third-wave approach to parenting interventions for parents of children with disabilities. Our aim is to examine the efficacy of parenting interventions incorporating mindfulness or acceptance in improving child and/or parental adjustment.

Method

Search Strategy

During June 2012, searches were conducted on the following databases: Medline, PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Web of Science. The search strategy comprised the following keywords:

-

1.

Mindfulness OR acceptance and commitment therapy

AND

-

2.

Parent training OR parent intervention OR parenting intervention OR parent therapy OR behavioural family intervention OR behavioural family intervention OR family intervention OR family therapy

Selection Criteria

Studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

1.

The intervention was delivered to parents of children with disabilities.

-

2.

The intervention included a mindfulness or acceptance component.

-

3.

The study assessed child adjustment or parental adjustment as an outcome. Measures of child adjustment included measures of externalising behaviour.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data extracted from each study included study design, population demographics, intervention type and outcome. It was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis due to the limited research found, the lack of common outcome variables and the fact that most studies did not report standard deviations.

Results

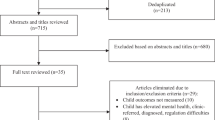

The search revealed 142 references. Of these, 124 were excluded based on title and abstract, as they were not related to parenting and mindfulness. The remaining 12 papers were examined in depth; two were excluded because they did not examine parental or child adjustment as an outcome variable, five were excluded because the participants were not parents of children with disabilities and seven were excluded because they were not empirical papers. As shown in Fig. 1, four remaining papers met the inclusion criteria.

Participant Characteristics

As presented in Table 1, the four included papers comprised the following participants: parents of children with autism spectrum disorders (Blackledge and Hayes 2006; Singh et al. 2006), parents of children with developmental disabilities (Singh et al. 2007) and parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Van der Oord et al. 2012).

Types of Intervention

Blackledge and Hayes (2006) tested an ACT intervention based on ACT as outlined in Hayes (2004). The intervention was delivered in groups. Singh et al. (2006, 2007) used a mindfulness intervention with formal mindfulness practice in the style of meditations, including mindfulness of breathing, mindfulness of child, nonjudgmental acceptance and loving-kindness meditations. Van der Oord et al. (2012) tested a mindfulness intervention based on MBSR and MBCT, which was offered simultaneously to both parents and children (see Table 2).

Qualitative Analysis

All of the papers located were pre–post design only. As shown in Table 3, in both studies, Singh et al. (2006, 2007) used a multiple baseline across subjects design with a lengthy practice period after completion of the intervention and a 1-year follow-up. Blackledge and Hayes (2006) used a within-subject repeated-measures design with two assessment points at baseline to attempt to control for change over time. Van der Oord et al. (2012) used a similar within-subject repeated-measures design with a within-group waitlist; that is, with two assessment points before the start of the intervention to attempt to control for change over time. Van der Oord et al. (2012) tested both a mindfulness intervention for parents and a mindfulness intervention for the child simultaneously. Thus, it is not possible to separate the effects of the parenting intervention.

Parental Adjustment and Child Adjustment Outcomes Investigated

As presented in Table 3, in both papers, Singh et al. (2006, 2007) measured child aggression by the frequency of aggressive behaviours per week recorded by the parent. In addition, Singh et al. (2007) included a measure of parental adjustment focusing on parenting stress, the Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Van der Oord et al. (2012) included the same measure, the PSI along with a questionnaire measuring child adjustment (Disruptive Behaviour Disorder Rating Scale (DBDRS))—both a parent- and a teacher-report version. Blackledge and Hayes (2006) measured parental adjustment using several indices, the Global Severity Index (GSI), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the General Heath Questionnaire (GHQ).

Reported Results

As reported in Table 4, Blackledge and Hayes (2006) found significant improvements in parental adjustment from pre-intervention to post-intervention in terms of decreases in depressive symptoms (BDI) and psychological symptoms (GSI). In addition, they found significant improvements from pre-intervention to follow-up 3 months later in terms of decreases in depressive symptoms (BDI) and psychological symptoms (GSI and BSI). Van der Oord et al. (2012) found significant improvements in parenting stress as measured by the PSI. For child adjustment, they found significant changes in the parent-report version of the DBDRS only; specifically, there were improvements to DBDRS inattention and DBDRS hyperactivity scales from pre-intervention to post-intervention and from pre-intervention to follow-up. They advise caution in interpreting these results because they did not find changes in the teacher-report version of the DBDRS. As both papers by Singh et al. (2006, 2007) involved a multiple baseline across subjects design, the effects were not tested statistically; however, each family improved over time, with decreases in child aggression and parenting stress. In particular, there was a decrease in child aggression during the practice period from the end of the intervention to follow-up 1 year later.

Discussion

Recently, there has been a call for research on third-wave parenting interventions (Cohen and Semple 2010; Dumas 2005; Duncan et al. 2009; Greco and Eifert 2004). This review suggests that third-wave parenting interventions may improve parental and child adjustment in families that have children with disabilities. The four papers reviewed provide tentative evidence that mindfulness-based interventions for parents of children with disabilities may be associated with decreases in parenting stress (Singh et al. 2007; Van der Oord et al. 2012), decreases in parental psychological symptoms (Blackledge and Hayes 2006), decreases in child aggression (Singh et al. 2006, 2007) and decreases in ADHD symptoms (Van der Oord et al. 2012). Further, the families within the studies of Singh et al. (2006, 2007) showed the most gains throughout the practice period from the completion of intervention to follow-up 1 year later. This suggests that the continuing practice of mindfulness in the absence of intervention may have additive effects above and beyond the intervention alone. However, it must be noted that this has not been tested statistically; it requires further research. Although the existing literature is promising, this review also makes clear the limited research in this area. Firm conclusions cannot be made from the current state of the literature. In particular, there is an urgent need for randomised controlled trials of third-wave parenting interventions with families of children with disabilities to establish the efficacy of this approach in improving parental and child adjustment.

Parents of children with disabilities parent within an emotional context that may include significant stress (Gupta 2007; Rentinck et al. 2007), increased risk of anxious/depressive symptoms (Barlow et al. 2006; Lach et al. 2009) and grief (Eakes et al. 1998; Whittingham et al. 2013). Third-wave cognitive behavioural interventions may form part of the support of parents of children with disabilities and decrease their risk of psychopathology.

Interventions based on mindfulness and acceptance may also assist parents of children with disabilities in flexible parenting—responding to the unique developmental needs of their child in the present moment, even in the presence of significant parental stress. Flexible and mindful parenting involves increasing psychological contact with one’s children as they are in the here and now including their present-moment developmental needs and the real-time contextual contingencies operating within the parent–child relationship. This may be particularly beneficial to parents of children with disabilities, as clinical experience suggests that the developmental needs of children with disabilities and the contingencies regulating their behaviour are more likely to be unique.

Parents of children with disabilities are not able to use developmental norms as a rule of thumb for developing realistic expectations of their children in the same way that parents of typically developing children often do. Further, they are more likely to find themselves in a parenting situation where generalised parenting rules of thumb—even good generalised parenting rules of thumb (e.g. ‘he’s probably doing it for attention; just ignore it’)—fail to accurately track the contingencies regulating their child’s behaviour and hence are not helpful. A flexible, mindful parenting approach may assist parents of children with disabilities in finding unique solutions for unique parenting problems. Further, as children with developmental disabilities are at an increased risk of emotional and behavioural problems, the optimisation of their parents’ ability to parent in a manner that supports healthy socioemotional development is important. Flexible, mindful parenting may be considered a preventative intervention for emotional and behavioural problems in children with disabilities.

Further research on third-wave parenting interventions with parents of children with disabilities is needed. In particular, randomised controlled trials are required to establish the efficacy of this approach for this population. It is also important for future research to separate the additive benefits of mindfulness and acceptance above and beyond traditional behavioural parenting interventions. In addition, future research could focus on whether interventions targeting both parents and children are more effective than interventions targeting either parents or children alone. The research of Singh et al. (2006, 2007) suggests that it may be important for future research to consider including a lengthy follow-up to obtain information about parents’ continued mindfulness practice. This review concentrated on the effects of third-wave parenting interventions on parental and child adjustment; however, research is also needed on the effects on other outcomes such as the parent–child relationship.

Third-wave parenting interventions have the potential to form an important part of efforts to support parents of children with disabilities. The existing literature is promising but limited. There is an urgent need for randomised controlled trials of third-wave parenting interventions with families of children with disabilities to establish the efficacy of this approach in improving parental and child adjustment.

References

Barlow, J. H., Cullen-Powell, L. A., & Cheshire, A. (2006). Psychological well-being among mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Early Child Development and Care, 176(3–4), 421–428.

Blackledge, J. T., & Hayes, S. C. (2006). Using acceptance and commitment training in the support of parents of children diagnosed with autism. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 28(1), 1–18.

Brereton, A., Tonge, B. J., & Einfeld, S. L. (2006). Psychopathology in children and adolescents with autism compared to young people with intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 863–870.

Carlsson, M., Olsson, I., Hagberg, G., & Beckung, E. (2008). Behaviour in children with cerebral palsy with and without epilepsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 50(10), 784–789.

Cohen, J. A. S., & Semple, R. J. (2010). Mindful parenting: a call for research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 145–151.

Coyne, L. W., & Wilson, K. G. (2004). The role of cognitive fusion in impaired parenting: an RFT analysis. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 4(3), 469–486.

Dumas, J. E. (2005). Mindfulness-based parent training: strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 779–791.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270.

Eakes, G. G., Burke, M. L., & Hainsworth, M. A. (1998). Middle-range theory of chronic sorrow. Image – the Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 30(2), 179–184.

Einfeld, S. L., & Tonge, J. (1996). Population prevalence of psychopathology in children and adolescents with intellectual disability: I. Rationale and methods. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 40(2), 91–98.

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hoover, C. (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(3), 243–268.

Greco, L. A., & Eifert, G. H. (2004). Treating parent–adolescent conflict: is acceptance the missing link for an integrative family therapy? Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 11(3), 305–314.

Gupta, V. B. (2007). Comparison of parenting stress in different developmental disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 19, 417–425.

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy and the new behavior therapies. In S. C. Hayes, V. M. Follette, & M. M. Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance: expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. New York: The Guilford Press.

Kostanski, M., & Hassed, C. (2008). Mindfulness as a concept and a process. Australian Psychologist, 43(1), 15–21.

Lach, L. M., Kohen, D. E., Garner, R. E., Brehaut, J. C., Miller, A. R., Klassen, A. F., et al. (2009). The health and psychosocial functioning of caregivers of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31(8), 607–618.

Parkes, J., White-Koning, M., Dickinson, H. O., Thyen, U., Arnaud, C., Beckung, E., et al. (2008). Psychological problems in children with cerebral palsy: a cross-sectional European study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 405–413.

Parkes, J., White-Koning, M., McCullough, N., & Colver, A. (2009). Psychological problems in children with hemiplegia: a European multicentre survey. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 94(6), 429–433.

Rentinck, I. C. M., Ketelaar, M., Jongmans, M. J., & Gorter, J. W. (2007). Parents of children with cerebral palsy: a review of factors related to the process of adaptation. Child: Care, Health and Development, 33(2), 161–169.

Sawyer, M. G., Bittman, M., La Greca, A. M., Crettenden, A. D., Borojevic, N., Raghavendra, P., et al. (2011). Time demands of caring for children with cerebral palsy: What are the implications for maternal mental health? Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 52(4), 338–343.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Fisher, B. C., Wahler, R. G., McAleavey, K., et al. (2006). Mindful parenting decreases aggression, non-compliance and self-injury in children with autism. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders, 14(3), 169–177.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Singh, J., Curtis, W. J., Wahler, R. G., et al. (2007). Mindful parenting decreases aggression and increase social behaviour in children with developmental disabilities. Behaviour Modification, 31(6), 749–771.

Van der Oord, S., Bogels, S. M., & Pejnenberg, D. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(1), 139–147.

Whittingham, K., Wee, D., Sanders, M., & Boyd, R. (2013). Predictors of psychological adjustment, experienced parenting burden and chronic sorrow symptoms in parents of children with cerebral palsy. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39(3), 366–373.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge an NHMRC Postdoctoral Fellowship (631712).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whittingham, K. Parents of Children with Disabilities, Mindfulness and Acceptance: a Review and a Call for Research. Mindfulness 5, 704–709 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0224-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0224-8