Abstract

This study examined the relations among mindfulness, nonattachment, depressive symptoms, and suicide rumination in undergraduate college students (N = 552). Hypothesized pathways and mediation were tested using path analysis. As hypothesized, depressive symptoms were negatively associated with both mindfulness and nonattachment; and suicide rumination was negatively related to mindfulness and nonattachment, and positively associated with depressive symptoms. Moreover, the mindfulness–suicide rumination and nonattachment–suicide rumination associations were both in part, mediated by depressive symptoms. Implications for the improved treatment of young adults at risk for depression and suicidal behaviors are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suicide is a common societal problem with approximately one million deaths from suicide occurring each year around the world (Levi et al. 2003). In the USA, approximately 100 people commit suicide per day (CDC 2009) and suicide is the second leading cause of death among college students (Schwartz 2006). Research suggests that suicidal ideation is an important precursor to suicide attempts (May et al. 2012). A recent study found that approximately 10.4 % of college students have seriously considered suicide at least once in the past year, while a smaller percentage (3.4 %) have more persistent suicidal ideation (e.g., suicidal rumination; see Wilcox et al. 2010). Thus, understanding factors associated with suicidal ideation and/or suicidal rumination is an important area of research, particularly among college students (Zisook et al. 2012).

Depressive symptoms are positively associated with suicidal rumination (Smith et al. 2006). Arria et al. (2009) found that depressive symptoms were one of the most robust predictors of suicidal ideation, second only to poor social support. Similarly, Wilcox et al. (2010) found that depressive symptoms were nine times higher among individuals with persistent suicidal ideation (i.e., suicidal rumination) relative to those without suicidal ideation. Prospective (Holma et al. 2010) and longitudinal (May et al. 2012) research suggests that suicidality (both attempts and ideation) is a consequence of depressive symptoms. Thus, understanding factors that increase the rates of depressive symptoms is important for the prevention of suicidal ideation and behavior.

Cognitive vulnerability theories of depression [e.g., Beck’s theory of depression (Beck 1987), the Hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al. 1989), and the Response Style theory (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991)] suggest that negative cognitive styles play an important role in the development and maintenance of emotional problems (Sutton et al. 2011). Negative cognitive styles both, precede and are risk factors for, depressive symptoms (Alloy et al. 2006; Garber & Carter 2006; Garber et al. 2009). Thus, the current state of the literature indicates that cognitive styles influence depressive symptoms, which in turn are associated with suicidal thoughts. A prominent cognitive theory of depression, the Response Style theory, proposes three cognitive response styles for dealing with negative events: rumination, distraction, and problem solving (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991). Although all three of these styles may influence depressive symptoms, rumination stands out as the most problematic response style (Just & Alloy 1997; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema 1991, 2000; O’Connor & Noyce 2008; Surrence et al. 2009). Rumination is the processes of self-focused attention, dominated by negative thoughts and feelings. Research suggests that the use of rumination can be particularly problematic, increasing the severity, duration, progression, and remission of depressive symptoms (Morrow & Nolen-Hoeksema 1990; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow 1991, 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1993). There has been much research on rumination and the factors that may protect against this form of response style. Curiously, several of these protective factors have come from an ancient spiritual tradition.

Recently, there has been considerable interest in the integration of Buddhist concepts into traditional psychological treatment (de Silva 1986; Mikulas 2007; Rubin 1996; Wallace & Shapiro 2006). Moreover, several of these concepts (e.g., mediation, mindfulness, and acceptance) have proven efficacious in the treatment of emotional problems (Bormann et al. 2012; Britton et al. 2012; Forman et al. 2007). Grounding these concepts within an established theoretical framework of depression (i.e., Response Style theory) has provided support for the mechanisms through which they affect change. For example, meditation has been found to alleviate depressive symptoms by decreasing rumination (Ramel et al. 2004). Shahar et al. (2010) found that the effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on depressive symptoms were mediated via changes in brooding, one form of rumination. Liverant et al. (2011) found modest support for the notion that acceptance partially mediates the association between sad mood and the use of rumination as a response style. Recently, a new Buddhist concept, nonattachment, has emerged as a potential protective factor against emotional dysfunction (Sahdra et al. 2010). However, the role of this new concept within the greater cognitive vulnerability models of emotional disorders has not been evaluated.

Examining Buddhist concepts in the context of ruminative response style reveals some interesting correlates. For example, rumination involves a negative focus on past experiences (Papageorgiou & Wells 2001; Wells & Papageorgiou 1998) which results in an inability to effectively problem solve current issues (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991) accompanied with a decrease in mental flexibility (Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema 2000). In other words, rumination promotes a fixation on past unhealthy mental representations, preventing a more adaptive response. Thus, rumination is comprised of two separate components: time (specifically past oriented) and context (unhealthy mental fixations). From this perspective, mindfulness may be seen as a way to reduce ruminative responses by diminishing the tendency to focus on the past (i.e., the time component). We posit nonattachment may decrease emotional problems by promoting a detachment from unhealthy mental representations (i.e., the contextual component). The current study examines these two features of adaptive cognitive styles from the Buddhist tradition with the underlying hypothesis that these approaches to understanding the world may result in a decreased risk of suicidal thoughts through a negative association with depressive symptoms. Both of these concepts are discussed in greater detail below.

Mindfulness is a Buddhist concept, and is defined as the psychological characteristic of being aware of the present moment and attending to current emotions, cognitions, and physiological states (Wallace & Shapiro 2006). It is thought to be comprised of at least two separate components (attention/awareness and acceptance; Bishop et al. 2004; Brown & Ryan 2003) that make up five different facets of mindfulness functioning (Baer et al. 2008a, b; Christopher et al. 2012). Research suggests that this “present focused” form of attention is positively associated with psychological well-being (Bowlin & Baer 2012). In previous research, mindfulness has been negatively associated with several aspects of maladaptive psychological functioning including depressive symptoms, anxiety, and rumination to name a few (Bowlin & Baer 2012; Kiken & Shook 2012). Mindfulness is also broadly associated with life satisfaction, self-esteem, and optimism, (Keng et al. 2011) all of which are inversely associated with suicidal ideation (Chioqueta & Stiles 2007; Creemers et al. 2012; Hirsch et al. 2007). Finally, Frewen et al. (2008) found that mindfulness was inversely associated with negative automatic thoughts. Thus, mindfulness may increase psychological health by influencing cognitive styles. Consistent with this notion, research indicates that mindfulness interventions modify negative cognitive styles. For example, Crane et al. (2008) found that an 8-week mindfulness-based intervention, among depressed patients in recovery with a history of suicidal behavior, resulted in decreased discrepancy from their ideal self (i.e., they evaluated themselves closer to who they ideally wished to be), relative to a control group. Consequently, mindfulness has become an important aspect of many treatment protocols (Hofmann et al. 2010).

A far less researched topic is the concept of nonattachment. Nonattachment is a state of autonomy in which an individual develops a sort of “detachment” from mental fixations that have the potential to cause psychological distress (Sahdra et al. 2010). It is closely aligned to the Western concept of acceptance in which a person is able to “let go” of unhealthy mental fixations. According to Buddhist writings, nonattachment promotes feelings of autonomy, security, and empathy (e.g., Chödrön 2003; Rosenberg 2004). Research has shown that nonattachment is negatively associated with depressive symptoms and overall psychological well-being (Sahdra et al. 2010). Nonattachment promotes psychological health by allowing individuals to assign value to life that is independent of objects, be it people, situations, or material possessions, over which we have little control. In other words, nonattachment represents a form of mental flexibility and the capacity to “let go” of things that have the potential to cause us psychological harm. This may be particularly important in the context of the Response Styles theory as research suggests that rumination promotes mental inflexibility (Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema 2000). For this reason, depressive symptoms, which are typically associated with negative mental fixations resulting in rumination (Hankin et al. 2009), are hypothesized to be lower for individuals with greater nonattachment.

The current study examines the association between suicidal rumination and two cognitive styles from the Buddhist tradition, mindfulness, and nonattachment. However, as noted above, both mindfulness and nonattachment appear to be inherently intertwined with the concept of acceptance. Given this shared underlying association, it is unclear whether or not nonattachment has anything to offer by way of protective features above and beyond that of mindfulness. It is expected that a better understanding of the interplay among these variables may have implications for the treatment of depressed young adults at risk for suicide. Specifically, on the basis of existing literature and consistent with theory, we hypothesized that: (1) Depressive symptoms would be negatively associated with both mindfulness and nonattachment; (2) suicide rumination would be negatively associated with mindfulness and nonattachment, and positively associated with depressive symptoms; and (3) depressive symptoms would significantly mediate the relation between both mindfulness and nonattachment and suicide rumination.

Method

Participants

Data were analyzed from a sample of 552 undergraduate students (77.2 % female, 22.8 % male), ages 18–26 years (M age = 19.85, SD = 1.66) from a university in the southeastern USA. The majority of participants described their race/ethnicity as Caucasian (n = 437, 79.2 %), followed by African American (n = 48, 8.7 %), Hispanic/Latino (n = 23, 4.2 %), Asian American (n = 15, 2.7 %), Native American (n = 4, 0.7 %), and an additional 4.5 % (n = 25) of the sample indicated “other” for race/ethnicity. Freshmen made up the largest group in the sample (n = 238, 43.1 %), followed by juniors (n = 115, 20.8 %), sophomores (n = 103, 18.7 %), and seniors (n = 96, 17.4 %). Three hundred nineteen (57.8 %) of the participants reported they were not in a relationship and 51.8 % (n = 286) of the students reported living on campus. Of the students who participated in the study, 24.8 % (n = 137) indicated that they were a member of a social fraternity or sorority.

Measures

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan 2003)

A 15-item, self-report measure, which is designed to assess a core characteristic of dispositional mindfulness, namely, open or receptive awareness of and attention to what is taking place in the present (e.g., “It seems I am running automatic without much awareness of what I’m doing”). Participants rate the degree to which they function mindlessly in daily life, using a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). Total scores range from 15 to 90, with higher scores denoting greater mindfulness. The MAAS has good internal consistency (i.e., Cronbach’s α), ranging from 0.82 to 0.87 (Brown & Ryan 2003). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was 0.90.

The Nonattachment Scale (NAS; Sahdra et al. 2010)

A 30-item self-report measure designed to assess nonattachment in the college student and general adult population. According to the authors of the scale, nonattachment is a subjective quality characterized by a relative absence of fixation on ideas, images, or sensory objects, as well as an absence of internal pressure to get, hold, avoid, or change circumstances or experiences. The nonattached state of mind is equanimous, flexible, and receptive, which is in contrast to a grasping, anxious, needy, or rigid state of mind. Notably, the concept of nonattachment is related to secure attachment in Western psychological terms (e.g., closeness, allowing others to be as they are, without manipulation, neediness, or judgment; Sahdra et al. 2010). A sample item on the NAS is “when pleasant experiences end, I am fine moving on to what comes next.” Across several studies, the NAS has shown excellent psychometric properties. Factor analyses with undergraduate and nationally sampled adult populations have confirmed a single factor scale structure (Sahdra et al. 2010). Internal consistency levels (Cronbach’s alphas) are above 0.80 and the NAS has demonstrated high test–retest reliability, discriminant and convergent validity, known-groups validity, and criterion validity. In the current study, the internal consistency reliability estimate was 0.94.

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck 1987)

A widely used 21-item self-report measure of severity of depressive symptoms experienced within the past 2 weeks. The items (i.e., groups of specific statements) are scored from 0 to 3 to assess the level of symptom severity. Responses on the items are summed to derive a total scale score, with higher scores suggestive of higher depressive symptom severity. An example of an item on the BDI-II is “Sadness,” with response options being 0 (I do not feel sad), 1 (I feel sad much of the time), 2 (I am sad all of the time), and 3 (I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it). Good estimates of internal consistency and concurrent validity have been demonstrated in clinical and nonclinical samples (Bisconer & Gross 2007; Naragon-Gainey, Watson, & Markon 2009). For example, Osman, Kopper, Barrios, Gutierrez, and Bagge (2004) found that scores on BDI-II were correlated with measures of suicide risk and other measures of depression. The total score on the BDI-II was positively skewed (1.48) and leptokurtic (2.90), so we conducted a natural log transform of the score (plus one) to address normality issues with resulting skewness being acceptable (−0.41) and slightly negative kurtosis (−0.86). In the current study, the estimate of internal consistency reliability of the BDI-II among university undergraduates was 0.92.

The Suicide Anger Expression Inventory-28 (SAEI-28; Osman et al. 2010)

A 28-item self-report instrument assessing anger expression and suicide-related constructs. Specifically, the SAEI-28 evaluates suicide rumination, maladaptive expression, reactive distress, and adaptive expression with seven content-specific items each. Each participant rated the items from 1 (not at all true of me) to 5 (extremely true of me). Given that the suicide rumination scale was found to be the strongest predictor among the four subscales of suicidal ideation and behavior in the initial evaluation study (Osman et al. 2010), we focused on the seven-item suicide rumination subscale of the SAEI-28 in the current study. Suicide rumination refers to the tendency to focus repeatedly on death and a range of suicidal behaviors. Examples of items on the suicide rumination scale include “I seriously consider ending my life”, “I deliberately harm or hurt myself”, and “I find myself wishing I were dead.” Previous research has demonstrated a positive and significant association between ruminative thoughts and feelings and (1) suicidal behaviors including suicidal ideation and attempts (Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema 2007; O’Connor & Noyce 2008), and (2) psychological disorders including depression and anxiety (Smith et al. 2006). The measure has been established to demonstrate good internal consistency reliability in undergraduate college students (Osman et al. 2010). In the current study, the reliability estimate was 0.93. The suicide rumination scale of the SAEI-28 showed a large floor effect, rendering normal theory statistics inappropriate. For the purposes of this study, we treated this scale as left-censored normal, using a weighted least squares estimator.

In addition to age, gender, and ethnicity, participants self-reported on year in school, social club membership (i.e., fraternity affiliation; no/yes), relationship status (not currently in a relationship vs. currently in a relationship), and residency status (on campus vs. off campus). Additionally, given that researchers (e.g., Miotto & Pretti 2008) have found that those who scored higher on measures of social desirability reported fewer thoughts about suicide, social desirability was also included as a covariate.

The Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale-Form B (MCSD-B; Reynolds 1982)

A measure designed to assess whether participants respond in a socially desirable manner and was included in the model as a possible covariate. The scale consists of 12 true–false items and was developed from the original Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe 1960), which measures the response tendency to make socially desirable self-presentations, especially on self-report measures. Psychometric information regarding the MCSD-B indicates that it has an adequate internal consistency estimate of 0.76, and, in similar research using college students, the alpha was 0.88 (Spanierman & Heppner 2004). The internal consistency estimate in the current sample was 0.68.

Procedure

Data collection was conducted through an online survey over the course of the spring semester. Participants voluntarily chose to complete the survey outside of class time in return for extra credit in their psychology course. Students were told of the study in regularly scheduled classes and through a posting on the online participant pool site. Participants completed a demographic survey and the study measures, which were presented in a randomized order. Prior to data collection, electronic informed consent was obtained from participants. They were advised that some items in the survey were personal in nature and that the participants would remain anonymous. Participants were advised that they were free to leave any items blank. No negative reactions were reported by participants. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study in advance of data collection, and ethical procedures were followed throughout the study.

Results

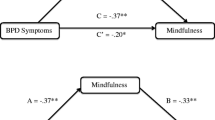

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the four primary study variables—mindfulness, nonattachment, (log−) depressive symptoms, and suicide rumination, are presented in Table 1. All correlations are significant, ps < .001. These results are consistent with Hypotheses 1 and 2. In order to further test the relations among study constructs in the context of the mediational model, we examined these relations as paths, adjusting for sociodemographic covariates and social desirability, which were modeled as exogenous predictors of the study variables. The model is diagrammed in Fig. 1, with standardized coefficients shown. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, depressive symptoms were negatively associated with mindfulness (b = −0.31, 95 % CI −0.41, −0.21) and nonattachment (b = −0.41, 95 % CI −0.54, −0.28). As expected and in line with Hypothesis 2, suicide rumination was negatively associated with both mindfulness (b = −1.69 95 % CI, −2.98, −0.45) and nonattachment (b = −4.87, 95 % CI −6.47, −3.27), and positively related to depressive symptoms (b = 2.68, 95 % CI 1.45, 3.95).

Mediated paths and total effects were tested as the product of coefficients in the same saturated path model estimated in Mplus v.6.1 (Muthen & Muthen 2010), using the software’s facility for maximum likelihood estimation in the context of missing data. The null hypothesis is that the sum of the two indirect paths—from the independent vairables (mindfulness and nonattachment) to the mediator (depressive symptoms) and from the mediator to the outcome (suicide rumination) is equal to zero, indicating no indirect effect. Due to the inclusion of a censored variable (suicide rumination), we used mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimation. We tested for the significance of indirect (mediated) effects using the percentile bootstrap with 3,000 draws to generate empirical confidence intervals for the products of the coefficients composing the mediated paths, one of the methods recommended by MacKinnon (2008) for specific indirect effects.

The total effect of mindfulness on suicide rumination was negative and significant, with a point estimate of −2.53, 95 % CI −3.75, −1.32, standardized estimate of −0.20. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, this effect was significantly mediated by depressive symptoms, ab = −0.84, 95 % CI −1.38, −0.40. Similarly, the total effect of nonattachment on suicide rumination was negative and significant, with a point estimate of −5.98, 95 % CI −7.54, −4.45, standardized estimate of −0.40. As expected, this effect was also significantly mediated by depressive symptoms, ab = −1.11, 95 % CI −1.77, −0.54.

Discussion

The current study examined the Buddhist concepts of mindfulness and nonattachment as features of adaptive cognitive styles that may be inversely associated with suicidal rumination through depressive symptoms. The results supported the proposed hypotheses. Depressive symptoms were negatively associated with both mindfulness and nonattachment and positively associated with suicidal rumination. There was an inverse association between suicidal rumination and both mindfulness and nonattachment. The relations between both nonattachment and mindfulness and suicidal rumination were partially mediated via depressive symptoms. Each of these findings is discussed in turn below.

Considerable research has supported the notion that depressive symptoms are positively associated with suicidal rumination (O’Connor & Noyce 2008; Smith et al. 2006; Surrence et al. 2009). The current findings add to this literature and extend it by identifying two potential features of adaptive cognitive styles which may affect this association. The two cognitive style features examined in the current study, mindfulness, and nonattachment, come from the Buddhist tradition. Although conceptually linked, these factors showed independent associations with suicidal rumination both via indirect effects on depressive symptoms and via alternative mechanisms.

The use of mindfulness-based psychotherapies as a mechanism to reduce depression is becoming increasingly popular (Hofmann et al. 2010). Mindfulness involves focusing on current thoughts, feelings, and sensations (Ekman et al. 2005). This present focused orientation is inversely associated with negative emotional experiences and an adaptive cognitive style. This may reduce both past oriented negative cognitions (i.e., rumination) and future oriented negative cognitions (i.e., worry). Previous research has shown that increasing mindfulness results in lower rates of depressive symptoms (Crane et al. 2008; Hofmann et al. 2010; Kuyken et al. 2008). In addition, mindfulness is increasingly being used as a treatment for suicidal outcomes (Hargus et al. 2010; Williams et al. 2006; Williams & Swales 2004). Consistent with the notion that mindfulness is an important facet of psychological health, we found an inverse association between mindfulness and depressive symptoms. It was hypothesized that this relation may serve as a protective factor against suicidal rumination. Although this was true, the association between mindfulness and suicidal rumination was not fully mediated by depressive symptoms. In fact, mindfulness also exhibited a strong direct effect on suicidal rumination. Thus, mindfulness appears to reduce suicidal rumination via two distinct pathways. Given that mindfulness has also been inversely associated with other forms of psychological distress (Bowlin & Baer 2012; Britton et al. 2012; Hofmann et al. 2010; Kiken & Shook 2012), future research may seek to examine the effects of mindfulness on other forms of psychological health, such as anxiety and stress, to identify additional protective mechanisms on suicidal rumination.

The concept of nonattachment is far less researched than that of mindfulness. Nonetheless, research has shown that nonattachment is positively associated with overall psychological well-being (Sahdra et al. 2010). Furthermore, this concept is characterized as a form of mental flexibility and acceptance, key features of adaptive cognitive styles which protect against depressive symptoms (Southwick et al. 2005). Thus, we hypothesized it may be inversely associated with suicidal rumination via reduced depressive symptoms. This hypothesis was supported. Although as with mindfulness, the association between nonattachment and suicidal rumination was not fully mediated by depressive symptoms. In fact, nonattachment showed a robust inverse association with suicidal rumination, which was much stronger than the inverse association between mindfulness and suicidal rumination (the bivariate associations also mirror this relation). Given the limited research on nonattachment, it is difficult to definitively say why this occurs. Nonattachment represents an individual’s mental flexibility and ability to detach from unhealthy mental fixations. This may be particularly important for suicidal rumination. Examining the extent to which nonattachment affects other suicidal outcomes is warranted. Future research may also benefit by identifying additional mechanisms through which nonattachment affects suicidal rumination. For example, research examining the association between nonattachment and other aspects of adaptive cognitive styles (e.g., negative attention biases, ideal-self discrepancies, negative automatic thoughts, etc.) may provide additional insights into the robust direct inverse association observed between nonattachment and suicidal rumination. Finally, previous research has shown that interpersonal insecurity (i.e., thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) is associated with suicidal outcomes (Van Orden et al. 2008). Given that nonattachment shares some similarities with the Western concept of secure interpersonal functioning, it may be interesting to evaluate its association with suicidal outcomes in the context of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior (Joiner & Silva 2012; Joiner et al. 2009).

Limitations

Although our findings contribute to the extant literature and clinical practice by exploring a theory-driven model of risk factors for suicide rumination in college students, there are limitations to the study worth noting. First, the sample consisted predominantly of young adult European–American college students at a single university, and so the results may not be generalizable to other samples, such as clinical inpatients, older adults, and minorities. Future research that replicates our findings in other samples, including a college student sample currently receiving psychological or psychiatric treatment, would allow for cross-validation of the current results. Second, although we included a measure of social desirability as a covariate in the analyses, the current study was limited to self-report data, which raises the potential problem of response bias. This socially desirable responding may increase the chances of finding associations that are due to shared method variance, rather than demonstrating real relations among constructs. Future studies should utilize a multimodal data collection strategy with college students such as conducting interviews with the participants in addition to administering self-report questionnaires.

Third, there are other possible mediators that may also account for the relation between mindfulness, nonattachment and suicide rumination. Variables to consider might include hopelessness and reasons for living. Fourth, given that the suicide rumination scale of the SAEI-28 has been found to be most strongly associated with suicidal ideation and behaviors, we did not examine the other three subscales as outcomes in the current study. However, we encourage researchers to investigate associations between suicide risk and protective factors and the maladaptive expression, reactive distress, and adaptive expression subscales of the SAEI-28 in addition to the suicide rumination subscale in future studies. Fifth, data collection was cross-sectional, which precludes conclusions about the causal nature of the independent and mediating variables. Based on study design, we can only conclude that these variables are associated with each other; therefore, further longitudinal research is warranted to verify that the hypothesized pathways are correct.

Finally, there are two separate measurement issues which must be considered in the interpretation of the current findings. First, there has been much research and discussion lately on the measurement of mindfulness (Baer et al. 2006a, 2008b; Bohlmeijer et al. 2011; Brown & Ryan 2004; Grossman 2008). In general, research has suggested mindfulness comprises a five-factor model. The current measure (i.e., the MAAS) appears to tap into one primary mindfulness dimension, “awareness of action” (see Baer et al. 2006a). Although this facet is consistently related to psychological wellbeing and inversely related to depressive outcomes (Baer et al. 2006b; Bohlmeijer et al. 2011; Bowlin & Baer 2012), it may not be the only facet associated with suicidal rumination. Further, alternative facets/measures of mindfulness may show no relation with depression or suicidal rumination. For example, “observing,” a facet of mindfulness not tapped by the MAAS (Baer et al. 2006a), has been shown to be more related to stress than depressive symptoms (Bowlin & Baer 2012). Thus, future research may seek to examine the observed associations using a more comprehensive measure of the mindfulness construct. The last issue involves the theoretical underpinning proposed here. We hypothesized that mindfulness (as measured by the MAAS) operates to reduce depression via diminishing one feature of ruminative style. Although we did observe a negative association with suicidal rumination, we did not test associations with hypothesized precursors in the Response Style theory of depression (e.g., depressive rumination). This may represent the “alternative mechanism” discussed above, and future research should seek to evaluate the extent to which mindfulness mediates the association between theoretically relevant precursors and depressive symptoms/suicidal propensity.

Treatment Implications

Despite these limitations, the current findings hold several important treatment implications. Consistent with previous treatment research, it appears that mindfulness conveys a strong protective effect on depressive symptoms (Hofmann et al. 2010), which is a robust predictor of suicidal ideation (Arria et al. 2009; Lamis & Lester 2012, 2013). Although the current findings do not explicitly test the effects of mindfulness on depression or suicidal rumination, they do add additional rationale for the selection of mindfulness-based therapies as a treatment option for college student populations with depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts. The research on nonattachment is quite limited. There have been no previous studies examining nonattachment in a treatment context. The current findings suggest that nonattachment may be an influential factor in psychological well-being. The concept of nonattachment focuses on maintaining mental flexibility and acceptance which results in a degree of separation from mental fixations and a reduction in cognitive rigidity which may cause psychological distress. Reducing cognitive rigidity is often a goal (arguably the primary goal) of psychotherapy. Thus, incorporating aspects of nonattachment into a cognitive–behavioral-based approach may be beneficial for individuals at risk for suicide. Furthermore, a treatment approach that utilizes both mindfulness and nonattachment may provide added benefit as these concepts appear to influence depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts through different pathways. However, future research should examine this idea in a carefully controlled trial before any true treatment implications can be reached.

Summary and Conclusions

In summary, the current study examined two Buddhist concepts, mindfulness and nonattachment, as potential protective factors in the depression–suicidal rumination association. Both were found to have direct associations with suicidal rumination as well as indirect associations through diminished depressive symptoms. Our findings suggest that both mindfulness and nonattachment may be important concepts in the treatment of depression and suicidal thinking. Thus, incorporating these concepts into treatment protocols may increase treatment efficacy. However, there is currently no treatment research on nonattachment. Future research may seek to examine ways in which nonattachment can be instilled through a psychotherapeutic process. Furthermore, identifying ways in which nonattachment conveys protective effects may be particularly interesting. In conclusion, the findings suggest that these two Buddhist concepts may be particularly important for overall psychological health.

References

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: a theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358–372. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.96.2.358.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Whitehouse, W. G., Hogan, M. E., Panzarella, C., & Rose, D. T. (2006). Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(1), 145–156. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.115.1.145.

Arria, A. M., O’Grady, K. E., Caldeira, K. M., Vincent, K. B., Wilcox, H. C., & Wish, E. D. (2009). Suicide ideation among college students: a multivariate analysis. Archives of Suicide Research, 13(3), 230–246. doi:10.1080/13811110903044351.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., & Krietemeyer, H. (2006a). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006b). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. doi:10.1177/1073191105283504.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008a). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008b). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. doi:10.1177/1073191107313003.

Beck, A. T. (1987). Cognitive models of depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 1(1), 5–37.

Bisconer, S. W., & Gross, D. M. (2007). Assessment of suicide risk in a psychiatric hospital. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(2), 143–149. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.2.143.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph077.

Bohlmeijer, E., ten Klooster, P. M., Fledderus, M., Veehof, M., & Baer, R. A. (2011). Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment, 18(3), 308–320. doi:10.1177/1073191111408231.

Bormann, J. E., Thorp, S. R., Wetherell, J. L., Golshan, S., & Lang, A. J. (2012). Meditation-based mantram intervention for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized trial. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. doi:10.1037/a0027522.

Bowlin, S. L., & Baer, R. A. (2012). Relationships between mindfulness, self-control, and psychological functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 411–415. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.050.

Britton, W. B., Shahar, B., Szepsenwol, O., & Jacobs, W. J. (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy improves emotional reactivity to social stress: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 365–380. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2011.08.006.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present:mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Perils and promise in defining and measuring mindfulness: observations from experience. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 242–248. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph078.

CDC. (2009). Suicide and self-inflicted injury. Washington D.C: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Chioqueta, A. P., & Stiles, T. C. (2007). The relationship between psychological buffers, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: identification of protective factors. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 28(2), 67–73. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.28.2.67.

Chödrön, P. (2003). Comfortable with uncertainty: 108 teachings on cultivating fearlessness and compassion. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Christopher, M. S., Neuser, N. J., Michael, P. G., & Baitmangalkar, A. (2012). Exploring the psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 124–131. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0086-x.

Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., Duggan, D. S., Hepburn, S., Fennell, M. V., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and self-discrepancy in recovered depressed patients with a history of depression and suicidality. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(6), 775–787. doi:10.1007/s10608-008-9193-y.

Creemers, D. H. M., Scholte, R. H. J., Engels, R. C. M. E., Prinstein, M. J., & Wiers, R. W. (2012). Implicit and explicit self-esteem as concurrent predictors of suicidal ideation, depressive symptoms, and loneliness. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43(1), 638–646. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.006.

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24(4), 349–354. doi:10.1037/h0047358.

Davis, R. N., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and nonruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(6), 699–711. doi:10.1023/a:1005591412406.

de Silva, P. (1986). Buddhism and behaviour change: implications for therapy. In G. Claxton (Ed.), Beyond therapy: the impact of Eastern religions on psychological theory and practice (pp. 217–231). Dorset England: Prism Press.

Ekman, P., Davidson, R. J., Ricard, M., & Wallace, B. A. (2005). Buddhist and psychological perspectives on emotions and well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 59–63.

Forman, E. M., Herbert, J. D., Moitra, E., Yeomans, P. D., & Geller, P. A. (2007). A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Behavior Modification, 31(6), 772–799. doi:10.1177/0145445507302202.

Frewen, P. A., Evans, E. M., Maraj, N., Dozois, D. J. A., & Partridge, K. (2008). Letting go: mindfulness and negative automatic thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(6), 758–774. doi:10.1007/s10608-007-9142-1.

Garber, J., & Carter, J. S. (2006). Major depression. In R. T. Ammerman (Ed.), Comprehensive handbook of personality and psychopathology (Vol. 3, pp. 165–216). Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley.

Garber, J., Clarke, G. N., Weersing, V. R., Beardslee, W. R., Brent, D. A., Gladstone, T. R. G., et al. (2009). Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(21), 2215–2224. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.788.

Grossman, P. (2008). On measuring mindfulness in psychosomatic and psychological research. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 64(4), 405–408. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.02.001.

Hankin, B. L., Oppenheimer, C., Jenness, J., Barrocas, A., Shapero, B. G., & Goldband, J. (2009). Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: review of processes contributing to stability and change across time. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(12), 1327–1338. doi:10.1002/jclp.20625.

Hargus, E., Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., & Williams, J. M. G. (2010). Effects of mindfulness on meta-awareness and specificity of describing prodromal symptoms in suicidal depression. Emotion, 10(1), 34–42. doi:10.1037/a0016825.

Hirsch, J. K., Conner, K. R., & Duberstein, P. R. (2007). Optimism and suicide ideation among young adult college students. Archives of Suicide Research, 11(2), 177–185. doi:10.1080/13811110701249988.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. doi:10.1037/a0018555.

Holma, K. M., Melartin, T. K., Haukka, J., Holma, I. A. K., Sokero, T. P., & Isometsä, E. T. (2010). Incidence and predictors of suicide attempts in DSM-IV major depressive disorder: a five-year prospective study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(7), 801–808. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050627.

Joiner, T. E., Jr., & Silva, C. (2012). Why people die by suicide: further development and tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior. In P. R. Shaver & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), Meaning, mortality, and choice: the social psychology of existential concerns (pp. 325–336). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association.

Joiner, T. E., Jr., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Selby, E. A., Ribeiro, J. D., Lewis, R., et al. (2009). Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 634–646. doi:10.1037/a0016500.

Just, N., & Alloy, L. B. (1997). The response styles theory of depression: tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(2), 221–229. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.106.2.221.

Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006.

Kiken, L. G., & Shook, N. J. (2012). Mindfulness and emotional distress: the role of negatively biased cognition. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 329–333. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.031.

Kuyken, W., Byford, S., Taylor, R. S., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., et al. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 966–978. doi:10.1037/a0013786.

Lamis, D. A., & Lester, D. (2012). Risk factors for suicidal ideation among African American and European American College Women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36(3), 337–349. doi:10.1177/0361684312439186.

Lamis, D. A., & Lester, D. (2013). Gender differences in risk and protective factors for suicidal ideation among college students. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 27, 62–77. doi:10.1080/87568225.2013.739035.

Levi, F., La Vecchia, C., Lucchini, F., Negri, E., Saxena, S., Maulik, P. K., et al. (2003). Trends in mortality from suicide, 1965–99. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108(5), 341–349. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00147.x.

Liverant, G. I., Kamholz, B. W., Sloan, D. M., & Brown, T. A. (2011). Rumination in clinical depression: a type of emotional suppression? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 35(3), 253–265. doi:10.1007/s10608-010-9304-4.

MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, N.J. Earlbaum.

May, A. M., Klonsky, E. D., & Klein, D. N. (2012). Predicting future suicide attempts among depressed suicide ideators: a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.009.

Mikulas, W. L. (2007). Buddhism & Western psychology: fundamentals of integration. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 14(4), 4–49.

Miotto, P. P., & Preti, A. A. (2008). Suicide ideation and social desirability among school-aged young people. Journal of Adolescence, 31(4), 519–533. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.004.

Miranda, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2007). Brooding and reflection: rumination predicts suicidal ideation at 1-year follow-up in a community sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(12), 3088–3095. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.07.015.

Morrow, J., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1990). Effects of responses to depression on the remediation of depressive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(3), 519–527. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.3.519.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2010). Mplus User’s Guide, v 6.1. Los Angeles, CA.: Muthen and Muthen, UCLA.

Naragon-Gainey, K., Watson, D., & Markon, K. E. (2009). Differential relations of depression and social anxiety symptoms to the facets of extraversion/positive emotionality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(2), 299–310. doi:10.1037/a0015637.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.100.4.569.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115–121. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1993). Effects of rumination and distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cognition and Emotion, 7(6), 561–570. doi:10.1080/02699939308409206.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Morrow, J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1993). Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(1), 20–28. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.102.1.20.

O’Connor, R. C., & Noyce, R. (2008). Personality and cognitive processes: self-criticism and different types of rumination as predictors of suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(3), 392–401. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.007.

Osman, A., Kopper, B. A., Barrios, F., Gutierrez, P. M., & Bagge, C. L. (2004). Reliability and Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory--II with Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatients. Psychological Assessment, 16(2), 120–132. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.120.

Osman, A., Gutierrez, P. M., Wong, J. L., Freedenthal, S., Bagge, C. L., & Smith, K. D. (2010). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Suicide Anger Expression Inventory—28. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(4), 595–608. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9186-5.

Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (2001). Metacognitive beliefs about rumination in recurrent major depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 8(2), 160–164. doi:10.1016/s1077-7229(01)80021-3.

Ramel, W., Goldin, P. R., Carmona, P. E., & McQuaid, J. R. (2004). The effects of mindfulness meditation on cognitive processes and affect in patients with past depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(4), 433–455. doi:10.1023/b:cotr.0000045557.15923.96.

Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(1), 119–125. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38:1<119::AID-JCLP2270380118>3.0.CO;2-I.

Rosenberg, L. (2004). Breath by breath: the liberating practice of insight meditation. Boston, MA, USA: Shambhala.

Rubin, J. B. (1996). Psychotherapy and Buddhism: toward an integration. New York, NY, USA: Plenum Press.

Sahdra, B. K., Shaver, P. R., & Brown, K. W. (2010). A scale to measure nonattachment: a Buddhist complement to Western research on attachment and adaptive functioning. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(2), 116–127. doi:10.1080/00223890903425960.

Schwartz, A. J. (2006). College student suicide in the United States: 1990–1991 through 2003–2004. Journal of American College Health, 54(6), 341–352. doi:10.3200/jach.54.6.341-352.

Shahar, B., Britton, W. B., Sbarra, D. A., Figueredo, A. J., & Bootzin, R. R. (2010). Mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: preliminary evidence from a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(4), 402–418. doi:10.1521/ijct.2010.3.4.402.

Smith, J. M., Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (2006). Cognitive vulnerability to depression, rumination, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: multiple pathways to self-injurious thinking. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 36(4), 443–454. doi:10.1521/suli.2006.36.4.443.

Southwick, S. M., Vythilingam, M., & Charney, D. S. (2005). The psychobiology of depression and resilience to stress: implications for prevention and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 255–291. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143948.

Spanierman, L. B., & Heppner, M. J. (2004). Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites Scale (PCRW): Construction and Initial Validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(2), 249–262. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.51.2.249.

Surrence, K., Miranda, R., Marroquín, B. M., & Chan, S. (2009). Brooding and reflective rumination among suicide attempters: cognitive vulnerability to suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(9), 803–808. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.001.

Sutton, J. M., Mineka, S., Zinbarg, R. E., Craske, M. G., Griffith, J. W., Rose, R. D., et al. (2011). The relationships of personality and cognitive styles with self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 35(4), 381–393. doi:10.1007/s10608-010-9336-9.

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Gordon, K. H., Bender, T. W., & Joiner, T. E., Jr. (2008). Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 72–83. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.76.1.72.

Wallace, B. A., & Shapiro, S. L. (2006). Mental balance and well-being: building bridges between Buddhism and Western psychology. The American Psychologist, 61(7), 690–701. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.61.7.690.

Wells, A., & Papageorgiou, C. (1998). Relationships between worry, obsessive-compulsive symptoms and meta-cognitive beliefs. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(9), 899–913. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00070-9.

Wilcox, H. C., Arria, A. M., Caldeira, K. M., Vincent, K. B., Pinchevsky, G. M., & O’Grady, K. E. (2010). Prevalence and predictors of persistent suicide ideation, plans, and attempts during college. Journal of Affective Disorders, 127(1–3), 287–294. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.017.

Williams, J. M. G., Duggan, D. S., Crane, C., & Fennell, M. J. V. (2006). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of recurrence of suicidal behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(2), 201–210. doi:10.1002/jclp.20223.

Williams, J. M. G., & Swales, M. (2004). The use of mindfulness-based approaches for suicidal patients. Archives of Suicide Research, 8(4), 315–329. doi:10.1080/13811110490476671.

Zisook, S., Downs, N., Moutier, C., & Clayton, P. (2012). College students and suicide risk: prevention and the role of academic psychiatry. Academic Psychiatry, 36(1), 1–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.10110155.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lamis, D.A., Dvorak, R.D. Mindfulness, Nonattachment, and Suicide Rumination in College Students: The Mediating Role of Depressive Symptoms. Mindfulness 5, 487–496 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0203-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0203-0