Abstract

The extent to which rumination mediates the relation between mindfulness skills and depressive symptoms in nonclinical undergraduates (N = 254) was examined. Measures of mindfulness (Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills), ruminative brooding and reflective pondering (Ruminative Response Scale), and depressive symptomatology (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology) were administered. The contribution of mindfulness and rumination subscales was investigated in mediation analyses using the bootstrapping methodology. The relations among the mindfulness scales and rumination and depressive symptomatology were investigated. The results suggest that brooding partially mediated the relation from awareness to depressive symptomatology and from depressive symptomatology to awareness (higher levels of awareness result in lower levels of brooding and, as a result, lower levels of depressive symptomatology and vice versa). Brooding fully mediated the relation from accepting without judgment to depressive symptomatology (higher levels of accepting without judgment result in lower levels of brooding, which results in lower levels of depressive symptomatology). Brooding partially mediated the relation from depressive symptomatology to accepting without judgment (higher levels of depressive symptomatology result in higher levels of brooding and thus in lower levels of accepting without judgment). Reflective pondering fully mediated the relation from depressive symptomatology to observing (higher levels of depressive symptomatology result in higher levels of reflective pondering and thus in higher levels of observing). Mindful observing was negatively correlated with awareness and accepting without judgment. Mindful describing was unrelated to rumination. The current study helps clarify the relations between mindfulness and depression, as influenced by rumination. A necessary step will be to investigate these relations in a clinical population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is considered a leading cause of disability, resulting in major personal and social burden (World Health Organization 2008). A number of evidence-based therapies have been developed for the treatment of depression, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and short-term psychoanalytic therapy. Recently, mindfulness has gained increased popularity in the treatment of depression. Mindfulness is the practice of directing one’s attention to the present moment, observing and accepting thoughts, feelings, and sensations without judgment (Bishop et al. 2004). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) has been shown to reduce depression relapse in individuals who have experienced three or more depressive episodes (Ma and Teasdale 2004; Teasdale et al. 2000). Moreover, MBCT has also been shown to significantly reduce depressive symptoms immediately following intervention in depressed patients, compared to a waitlist control condition (Shahar et al. 2010). These findings suggest that mindfulness may have beneficial effects on depressive symptomatology. However, the exact processes by which mindfulness may influence depressive symptoms have not been fully elucidated. One promising candidate is rumination (e.g., Watkins et al. 2007).

Rumination is defined as repetitively thinking about a depressed mood and its causes, implications, and consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991). Rumination may be used as a strategy to deal with negative mood, but, paradoxically, often leads to a further decrease in mood (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema 1991; Treynor et al. 2003). As such, rumination has been considered an important maintenance factor in depression. Rumination remains elevated in depressed individuals even after depression treatment (Watkins et al. 2007). More specifically, several correlational, experimental, and longitudinal studies have shown that rumination is associated with longer and more severe periods of depressed moods (for comprehensive reviews, see Lyubomirsky and Tkach 2004; Nolen-Hoeksema 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008; Watkins 2008). Further, therapeutic techniques that specifically target rumination in individuals with residual depression have been shown to result in decreases in rumination and depressive symptoms (Watkins et al. 2007).

Recently, rumination has been seen as a multidimensional construct and the question has arisen whether rumination is entirely maladaptive. Treynor et al. (2003) were the first to conceptualize rumination into two components in a nonclinical sample: brooding and reflective pondering. Brooding refers to a “passive comparison of one’s current situation with some unachieved standard” (Treynor et al. 2003, p. 256). Brooding is also “moody” and engaging in brooding is done anxiously and gloomily. Reflective pondering, on the other hand, refers to “a purposeful turning inward to engage in cognitive problem solving to alleviate one’s depressive symptoms” (Treynor et al. 2003, p. 256). Reflective pondering is contemplative, yet neutrally valenced. Treynor et al. (2003) showed that reflective pondering was associated with more depressive feelings at present but less over time, whereas brooding was associated with more depressive feelings both at present and over time. Thus, reflective pondering may eventually lead to effective problem solving and relief of negative mood, whereas brooding does not. Treynor et al. (2003) have even recommended that future studies investigating rumination and depression should look at brooding and reflective pondering separately because these two components have different relations with depressive symptomatology (i.e., looking at rumination as a whole may result in a loss of information).

Several studies have confirmed the pattern of results originally found by Treynor et al. (2003) regarding the two factors of rumination. For instance, Burwell and Shirk (2007) have found that brooding, but not reflective pondering, is related to the development of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Moreover, brooding has been shown to mediate the relation between negative cognitive styles and depressive symptomatology, whereas reflective pondering did not (Lo et al. 2008). Another example comes from a study by Joormann et al. (2006), in which they confirmed the two-factor model of rumination set out by Treynor et al. (2003), but in a clinical sample of depressed patients, instead. To specifically determine if brooding was maladaptive and reflective pondering was adaptive, the authors investigated the relation between the two components of rumination and cognitive biases. Their results showed that brooding, but not reflective pondering, was related to biased attention for negative stimuli (e.g., sad faces).

While it may seem that brooding is the maladaptive form of rumination, the picture is complicated by several recent studies that suggest that reflective pondering is also maladaptive. For example, Verhaegen et al. (2005) have found a relation between reflective pondering and current levels of depression. Furthermore, Joormann et al. (2006) have cautioned that, in depressed individuals, reflective pondering and brooding can easily perpetuate each other. In a similar vein, it has been stated that reflective pondering may easily become maladaptive in individuals with a negative self-schema (Ingram et al. 1998). Therefore, brooding and reflective pondering may not occur in complete isolation in the individual, which could explain why reflective pondering is not necessarily adaptive (especially in depressed individuals; Takano and Tanno 2009). To date, the current consensus is that reflective pondering is generally a maladaptive process to engage in, despite some exceptions to the rule (see Watkins 2008).

Besides the relation between rumination and depressive symptomatology, evidence also suggests a relation between rumination and mindfulness. More specifically, individuals who score high on measures of mindfulness have lower scores on measures of rumination (Williams 2008) and mindfulness training has resulted in a significant pre–post decrease in rumination in otherwise healthy individuals experiencing significant amounts of stress (Jain et al. 2007). Whereas being mindful entails directing attention to the present moment in a nonjudgmental and accepting way, rumination is solely focused on and guided by past negative experiences, which inevitably draw attention away from the present moment. By cultivating mindfulness skills, one becomes skilled in directing attention to the present moment, which may facilitate directing attention away from ruminative thoughts. Furthermore, by practicing mindfulness, one becomes less judgmental of experiences (Barnard and Curry 2011; Dunkley and Grilo 2007; Germer 2009; Kiken 2011; Michalak 2011), thereby allowing ruminative thinkers to become less critical in their thinking. Moreover, mindfulness also creates cognitive defusion (Germer 2009), a process which enhances the ability to observe thought patterns, thereby enabling awareness of dysfunctional thought patterns (e.g., rumination). Another important aspect of cognitive diffusion in relation to rumination concerns the self-concept. Rumination and its impact on depressive symptoms is largely the result of ruminative thoughts defining the self (e.g., Lee-Flynn 2011; Moberly and Watkins 2008; Rüsch et al. 2010). Through mindfulness, the individual no longer identifies himself or herself by (critical, self-focused) thoughts. These theoretical mechanisms provide pathways through which increases in mindfulness levels could lead to decreases in rumination and, as a result, decreases in depressive symptoms. Conversely, through the same mechanisms, a depressed mood may foster more rumination which leads towards less present-focused and more judgmental awareness, thereby creating a less mindful state.

Taken together, it may be reasonable to suggest that rumination may mediate the relations between mindfulness and symptoms of depression. Accordingly, the aim of the current study was to examine the extent to which rumination mediates the relation between mindfulness skills and depressive symptoms. In the current study, levels of mindfulness skills, rumination, and depressive symptoms were measured cross-sectionally by self-report questionnaires. It was expected that both components of rumination (brooding and reflective pondering) would mediate the relations between mindfulness skills and depressive symptoms. In other words, higher levels of mindfulness skills were expected to result in lower levels of depressive symptomatology, via lower levels of brooding and reflective pondering. Conversely, higher levels of depressive symptomatology were expected to result in lower levels of mindfulness skills, via higher levels of brooding and reflective pondering. Finally, the relation between various mindfulness concepts was investigated, in order to further clarify the processes involved in mindfulness.

Method

Participants and Procedure

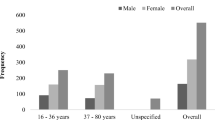

A total of 254 undergraduates (47 males, 207 females) of Maastricht University (The Netherlands) participated in this study and provided written consent. Mean age of the sample was 21.4 years (SD = 2.3). Individuals were compensated for their participation by course credit. All participants completed a set of questionnaires (see the “Measures” section) in a counterbalanced order. Respondents completed the measures in a conference room in groups of five to ten students. An experimenter was available to provide assistance and to ensure confidential, independent responding.

Measures

Mindfulness Skills

The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS; Baer et al. 2004) was used to measure mindfulness skills. The KIMS was designed to measure the general tendency to be mindful in daily life and is applicable to the general population, regardless of meditation practice. The participants rate 39 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (almost always or always true). The KIMS consists of the following four scales. The observing scale includes items relating to observing both internal and external sensations (e.g., “I pay attention to whether my muscles are tense or relaxed”; “I pay attention to sensations, such as the wind in my hair or sun on my face”). The describing scale includes items relating to describing experiences, feelings, and thoughts. (e.g., “I am good at finding the words to describe my feelings”; “I’m good at thinking of words to express my perceptions, such as how things taste, smell or sound”). The awareness scale includes items relating to focusing on the present moment, activities, and experiences (e.g., “When I’m doing something, I’m only focused on what I’m doing, nothing else”; “When I’m reading, I focus all my attention on what I’m reading”). Finally, the accepting without judgment scale includes items relating to accepting feelings, thoughts, and experiences without labeling them as inappropriate, bad, unacceptable, etc. (e.g., “I think some of my emotions are bad or inappropriate and I shouldn’t feel them”; “I tend to evaluate whether my perceptions are right or wrong,” with both of these items being reverse coded). The reliability and validity of the KIMS are supported (Baer et al. 2004).

Rumination

The Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991; Raes et al. 2003) was used to measure rumination. The RRS includes 22 items describing responses to depressed mood that are self-focused, symptom-focused, and focused on the possible causes and consequences of dysphoric mood (e.g., “Think about how sad I feel” and “Go someplace alone to think about my feelings”). Each item is rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The RRS is a reliable and valid measure of rumination (for an overview, see Luminet 2004). Although the complete RRS was administered, it was analyzed based on the brooding and reflective pondering subscales, each composed of five different items from the RRS (for details, see Treynor et al. 2003). Examples of brooding items include “Think, what am I doing to deserve this?” and “Think, why can’t I handle things better?,” whereas examples of reflective pondering items include “Analyze recent events to try to understand why you are depressed” and “Write down what you are thinking and analyze it.” Treynor et al. (2003) found the subfactors brooding and reflection to be reliable.

Depressive Symptoms

The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS; Rush et al. 2003) was used to measure symptoms of depression. The QIDS is a 16-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (e.g., mood, concentration, self-criticism, suicidal ideation, interest, energy/fatigue, sleep disturbance, decrease/increase in appetite/weight, and psychomotor agitation/retardation). Items are rated based on the past 7 days and are scored on a scale of 0 to 3. The total score ranges from 0 to 48. The reliability and validity of the QIDS are good and have been well documented (e.g., Rush et al. 2003).

Statistical Analysis

Mediation was assessed by examining indirect effects as employed by Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) bootstrapping procedure (with N = 5,000 bootstrap resamples). Bootstrapping circumvents the normality assumption applied to the indirect effect, which holds for the causal steps approach to mediation by Baron and Kenny (1986) and the use of the Sobel test (normal theory-based). Moreover, the model specified by Preacher and Hayes (2008) enables a determination of which mediator(s) is responsible for the mediating effect. In assessing indirect effects, 95 % (bias-corrected and accelerated) confidence intervals for the parameter estimates of the indirect effects were calculated. A parameter estimate of an indirect effect is significant in the case zero is not contained in the confidence intervals.

Eight bootstrapping analyses were conducted to investigate the mediating effect of rumination in the relation between mindfulness and depressive symptomatology. For all analyses, the mediators were the rumination subscales, brooding and reflective pondering. For the first four analyses, the independent variables were the four KIMS subscales and the dependent variable was depressive symptomatology. For each bootstrapping analysis, one KIMS subscale was tested while controlling for the other three KIMS subscales. This restrictive analysis was chosen to investigate the effects of the KIMS subscales partialled out for each other. For the next four analyses, the independent variable was depressive symptomatology and the dependent variables were the four KIMS subscales. Finally, it is important to note that only the significant results have been reported below.

Results

General Findings

All variables were standardized for the purpose of the mediation analysis. Scores of depressive symptomatology (QIDS) were transformed (using a logarithmic transformation) to a normal distribution as the data were positively skewed (skewness, 0.974; standard error, 0.153). Table 1 presents the general descriptive statistics, ratings of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas), and a correlation matrix of the measures under investigation. Please note that transformed values of the QIDS were used for the correlational analyses. Independent-samples t tests did not reveal significant gender differences on these measures. All measures showed adequate to good internal consistency (see alphas; see Table 1).

Relations Between Mindfulness, Rumination, and Depression

The subscales awareness and accepting without judgment of the KIMS showed a significant negative correlation with the rumination scales brooding and reflective pondering, whereas the observing subscale of the KIMS showed a significant positive correlation with both rumination scales. The describing subscale of the KIMS showed no significant correlation (see Table 1).

The awareness, accepting without judgment, and describing subscales of the KIMS all showed significant negative correlations with depressive symptomatology. Observing showed no significant correlation with depressive symptomatology. Both rumination scales, brooding and reflective pondering, were significantly positively correlated with depressive symptomatology (see Table 1). These correlations will help to clarify the results of the bootstrapping analysis.

Results of Bootstrapping Analyses

Regarding the mediating role of rumination from mindfulness skills to depressive symptomatology, brooding was a significant mediator in the relationship from the KIMS subscale awareness to depressive symptomatology (95 % CI, −0.11 to −0.01). So, greater levels of awareness result in lower levels of brooding and, as a result, in lower levels of depressive symptomatology. Brooding was also a significant mediator in the relationship from the KIMS subscale accepting without judgment to depressive symptomatology (95 % CI, −0.15 to −0.03). Therefore, greater levels of accepting without judgment result in lower levels of brooding and, as a result, in lower levels of depressive symptomatology. The direct effect of awareness on depressive symptomatology, controlling for brooding, was significant (p = 0.002), suggesting partial mediation; higher levels of awareness directly result in lower levels of depressive symptomatology. The direct effect of accepting without judgment on depressive symptomatology was nonsignificant (p = 0.096), indicating full mediation.

Concerning the role of rumination from depressive symptomatology to mindfulness skills, brooding was a significant mediator in the relationship from depressive symptomatology to the KIMS subscale awareness (95 % CI, −0.12 to −0.01). Thus, higher levels of depressive symptomatology result in higher levels of brooding and thus in lower levels of awareness. Further, brooding was a significant mediator in the relationship from depressive symptomatology to the KIMS subscale accepting without judgment (95 % CI, −0.22 to −0.01). In other words, higher levels of depressive symptomatology result in higher levels of brooding and, therefore, in lower levels of accepting without judgment. The direct effect of depressive symptomatology on awareness, controlling for brooding, was significant (p < 0.001), suggesting partial mediation. So, higher levels of depressive symptomatology directly result in lower levels of awareness. The direct effect of depressive symptomatology on accepting without judgment was significant (p = 0.049), also suggesting partial mediation and indicating that higher levels of depressive symptomatology also directly result in lower levels of accepting without judgment. Reflective pondering was a significant mediator in the relationship from depressive symptomatology to the KIMS subscale observing (95 % CI, 0.01–0.11). Therefore, higher levels of depressive symptomatology result in higher levels of reflective pondering and, as a result, in higher levels of observing. The direct effect of depressive symptomatology on observing, controlling for reflective pondering, was nonsignificant (p = 0.581), indicating full mediation. No other significant associations were found.

Relations Among the KIMS Subscales

The KIMS subscales describing, awareness, and accepting without judgment showed significant positive correlations with each other (see Table 1). The KIMS subscale observing showed a significant positive correlation with describing but significant negative correlations with awareness and accepting without judgment.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of rumination (i.e., brooding and reflective pondering) in the mutual relationships between mindfulness skills and symptoms of depression. Mediation analyses showed that brooding partially mediated the relationship between awareness and depressive symptomatology in both directions and from depressive symptomatology to accepting without judgment. Further, brooding fully mediated the relationship from accepting without judgment to depressive symptomatology. Reflective pondering fully mediated the relationship from depressive symptomatology to observing.

Investigation of the Main Concepts (Mindfulness, Rumination, and Depressive Symptomatology)

Awareness and accepting without judgment were the only KIMS subscales that were consistently associated with brooding and depressive symptomatology. The negative relation of awareness with rumination may be explained by awareness’ focus on the present moment. Contrary to rumination, present-focused awareness comprises the individual’s ability to focus entirely on the “here and now,” without drifting into past or future thoughts. Further, the individual no longer identifies with his or her thoughts and, instead, becomes what has been termed the “observing self” (e.g., “I am not my thoughts or emotions; rather I am the observer of thoughts and emotions”; Deikman 1982). From this perspective, it is possible to observe thought processes as separate from the self and, thus, to be fully in the present moment and see it clearly (unaffected by interpretations). The mediation analyses show that greater brooding may also relate to less awareness (i.e., being preoccupied and identified with thoughts).

As the direct effect of awareness on depressive symptomatology was significant, it is likely that awareness and depressive symptomatology may impact one another directly. When feeling down, some individuals may identify with the negative thoughts (e.g., “I am a sad person”). This identification with the depressed mood may lead to further decreases in mood and to feelings like hopelessness (e.g., Lee-Flynn 2011; Moberly and Watkins 2008; Rüsch et al. 2010). In contrast, by practicing awareness, individuals become aware of these dysfunctional thought patterns. Moreover, individuals become aware of these dysfunctional thought patterns for what they truly are: merely (transient) thoughts. This realization alone may lighten the emotional weight of the negative thoughts and may, therefore, lead to an increase in mood. Likewise, a depressed mood may make it challenging for one to practice awareness, as the individual may struggle to “solve” the depressed mood state, which is seen as a part of the self that needs challenging or fixing. Thus, increasing the mindfulness skill awareness may buffer against depressive symptoms.

The direct effect of depressive symptomatology on accepting without judgment was significant. Accepting without judgment may be beneficial because it trains the individual to accept, rather than to struggle against, his or her thoughts and interpretations—unlike a ruminative way of thinking. When the individual accepts these thoughts, without judgment, they can be more easily let go of (thus preventing a ruminative cycle). Also, whereas rumination is engaged in as a coping mechanism to solve a discrepancy between a current state and an ideal state, accepting without judgment trains the individual to be okay with this discrepancy and to stay in contact with the present moment.

Although brooding influenced the mutual relationships between mindfulness skills (awareness and accepting without judgment) and depressive symptomatology, reflective pondering only influenced the relationship from depressive symptomatology to the mindfulness skill observing. According to this relation, the greater the amount of reflective pondering, the greater the amount of observing. On one hand, these findings could be explained by the way observing is measured by the KIMS. Many of the KIMS observing items reflect self-focused observing (e.g., “I pay attention to whether my muscles are tense or relaxed”) which is similar to self-focused attention. Self-focused attention has been shown to be prominent in individuals with depressive symptoms (Ingram 1990). Thus, it is possible that reflective pondering may foster the self-focused observing that is captured by this KIMS subscale. On the other hand, it may also be possible that reflective pondering is indeed a constructive process (e.g., Joormann et al. 2006), one that might go hand in hand with beneficial skills such as greater mindful observing; it could then also be said that brooding is in fact the “greater of two evils” of rumination (e.g., Treynor et al. 2003). Of course, longitudinal research will be required in order to investigate this notion further.

Finally, it is likely that one or more underlying factors not measured in this study could have an effect on mindfulness and depressive symptomatology as well. One candidate is neuroticism, the tendency to experience negative states related to the self, the body, or emotions (Watson 2000). Fetterman et al. (2010) have stated that neuroticism systematically undermines mindfulness as it fosters worrying about future threats (Watson and Clark 1984) and impedes the ability to experience the present moment (Borkovec et al. 1998; Feltman et al. 2009). Some authors have also argued that rumination is a manifestation of neuroticism (Segerstrom et al. 2000) and is related to mood variability, depressive symptoms, and depression vulnerability (e.g., Saklofske et al. 1995). Other aspects that might affect the relations between mindfulness, rumination, and depressive symptoms may include emotional abilities such as emotional regulation or emotional intelligence (e.g., Fernandez-Berrocal et al. 2006). Finally, negative self-thinking may also mediate the relations between mindfulness and depressive symptoms (e.g., Verplanken et al. 2007). Negative self-thinking has been studied in terms of content (i.e., negative self-thoughts) and process (i.e., the way a person thinks). Negative self-thinking becomes habitual when it is frequent, uncontrollable, mentally efficient, and when it is engaged in without awareness. It has been shown that habitual negative self-thinking (i.e., the process aspect) is related to depression and mindfulness even when controlling for the content aspect of negative self-thinking (Verplanken et al. 2007). It may be interesting to incorporate habitual negative self-thinking in the study of mindfulness and depression in future research.

Analysis of the KIMS Subscales

Mindful observing was negatively associated with accepting without judgment, which has also been found in previous studies (e.g., Baum et al. 2010). In addition, a negative association between observing and awareness was also found which may be explained by the KIMS measurement of observing as described earlier. Describing was not significantly associated with brooding or reflective pondering, but did correlate with the remaining KIMS subscales. Similar to speculations regarding observing (Shapiro et al. 2006), Hansen et al. (2009) suggested that describing, taken on its own, is often judgmental in nature. It is only when describing is combined with a certain level of awareness and accepting without judgment that it is truly beneficial. Another important point is that the KIMS conceptualizes describing as taking place at an interpersonal level (e.g., “I am good at finding the words to describe my feelings”) which may encompass a healthier method of dealing with emotions (i.e., sharing with others). The unexpected findings regarding the relations between the KIMS subscales may raise alarm regarding the content validity of the KIMS. However, these patterns will have to be interpreted cautiously, given the limitations of the current study.

Limitations

The main limitation to the current study is that the mediation analysis was done on cross-sectional data, which allow for assessing indirect effects, rather than real mediation effects. Therefore, future research should also focus on experimental studies to examine and manipulate the underlying causal mechanisms of mindfulness and rumination on depression. Another limitation to the current study is that the sample population was a nonclinical population, so it remains to be determined if the current findings can be replicated in a clinical population. One motivation to use a nonclinical population is that the mechanisms underlying subclinical levels of depression are interesting in their own right. While many individuals suffer from clinical levels of depression, subclinical levels of depression should also be understood as they are common and may have an impact on an individuals’ functioning (e.g., Ornel et al. 1993; Wells et al. 1989, 1992). Furthermore, depressive symptomatology can be seen as a continuum, with lower levels in healthy populations and higher levels in clinical populations. In other words, variations in depressive symptomatology exist in both populations and depressive symptomatology is not exclusive to clinical populations. Therefore, the second motivation for using a nonclinical population is that the current results might provide a theoretical basis from which to better understand the underlying mechanisms in a clinical population; these mechanisms may or may not be similar. As the relation between mindfulness skills, rumination, and depressive symptoms have been found in a student sample, the next important step will be to conduct future research in samples with greater levels of depressive symptoms. Another point that needs to be addressed concerns the chosen theoretical model. Although a theoretical rational for the current model has been provided, other models cannot be ruled out. One possibility is that mindfulness may work as a mediator in the relation between rumination and depression. However, investigating this alternative model is beyond the scope of the current study. Finally, future studies may incorporate other possible factors, such as neuroticism or negative self-thinking, which may help clarify these relations.

The exact processes by which mindfulness may influence depressive symptoms had not been fully elucidated in the extant literature. The current study aimed to investigate the role of rumination (i.e., brooding and reflective pondering) in the mutual relationships between mindfulness skills and symptoms of depression. Despite its limitations, the current study’s results do suggest that brooding may be a mediator in the relation between mindfulness skills (awareness and accepting without judgment) and depressive symptomatology and that reflective pondering may be a mediator in the relation between depressive symptomatology and mindfulness skills (observing). Therefore, this study provides an initial indication of the intricate relations between mindfulness skills, rumination, and depression and offers a better understanding of how the components of these concepts influence one another. It will be an interesting and necessary step to investigate whether similar relations exist in a clinical population and, if so, how this knowledge can be used to improve clinical practice.

References

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report. The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment, 11, 191–206.

Barnard, L. K., & Curry, J. F. (2011). Self-compassion: conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15, 289–303.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Baum, C., Kuyken, W., Bohus, M., Heidenreich, T., Johannes, M., & Steil, R. (2010). The psychometric properties of the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills in clinical populations. Assessment, 17, 220–229.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241.

Borkovec, T. D., Ray, W. J., & Stoeber, J. (1998). Worry: A cognitive phenomenon intimately linked to affective, physiological, and interpersonal behavioural processes. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 561–576.

Burwell, R. A., & Shirk, S. R. (2007). Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: Associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms, and coping. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 56–65.

Deikman, A. J. (1982). The observing self: Mysticism and psychotherapy. Boston: Beacon.

Dunkley, D. M., & Grilo, C. M. (2007). Self-criticism, low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and over-evaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 139–149.

Fetterman, A. K., Robinson, M. D., Ode, S., & Gordon, K. K. (2010). Neuroticism as a risk factor for behavioural dysregulation: A mindfulness-mediation perspective. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 301–321.

Feltman, R., Robinson, M. D., & Ode, S. (2009). Mindfulness as a moderator of neuroticism-outcome relations: A self-regulation perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 953–961.

Fernandez-Berrocal, P., Alcaide, R., Extremera, N., & Pizarro, D. (2006). The role of emotional intelligence in anxiety and depression among adolescents. Individual Differences Research, 4, 16–27.

Germer, C. K. (2009). The mindful path to self-compassion: Freeing yourself from destructive thoughts and emotions. New York: Guilford.

Hansen, E. H., Lundh, L. G., Homman, A., & Wångby-Lundh, M. (2009). Measuring mindfulness: Pilot studies with the Swedish versions of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale and the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38, 2–15.

Ingram, R. (1990). Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and a conceptual model. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 156–176.

Ingram, R. E., Miranda, J., & Segal, Z. V. (1998). Cognitive vulnerability to depression. New York: Guilford.

Jain, S., Shapiro, S. L., Swanick, S., Roesch, S. C., Mills, P. J., & Bell, I. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination and distraction. Annals of Behavioural Medicine, 33, 11–21.

Joormann, J., Dkane, M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2006). Adaptive and maladaptive components of rumination? Diagnostic specificity and relation to depressive biases. Behaviour Therapy, 37, 269–280.

Kiken, L. G. (2011). Looking up: Mindfulness increases positive judgments and reduces negativity bias. Social Psychology and Personality Science, 2, 425–431.

Lee-Flynn, S. C. (2011). Daily cognitive appraisals, daily affect, and long-term depressive symptoms: The role of self-esteem and self-concept clarity in the stress process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 268.

Luminet, O. (2004). Measurement of depressive rumination and associated constructs. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 187–215). Chichester: Wiley.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Tkach, C. (2004). The consequences of dysphoric rumination. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 21–42). Chichester: Wiley.

Lo, C., Ho, S. M. Y., & Hollon, S. D. (2008). The effects of rumination and negative cognitive styles on depression: A mediation analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 487–495.

Ma, S. H., & Teasdale, J. D. (2004). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 31–40.

Michalak, J. (2011). Buffering low self-esteem: The effect of mindful acceptance on the relationship between self-esteem and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 751–754.

Moberly, N. J., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Ruminative self-focus and negative affect: An experience sampling study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 314–323.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569–582.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster. The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 115–121.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424.

Ornel, J., Von Korff, M., Van Den Bink, W., Katon, W., Brilman, E., & Oldehinkel, T. (1993). Depression, anxiety, and social disability show synchrony of change in primary care patients. American Journal of Public Health, 83, 385–390.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Raes, F., Hermans, D., & Eelen, P. (2003). De Nederlandstalige versie van de Ruminative Response Scale (RRS-NL) en de Rumination on Sadness Scale (RSS-NL). Gedragstherapie, 30, 147–163.

Rüsch, N., Corrigan, P. W., Todd, A. R., & Bodenhausen, G. (2010). Implicit self-stigma in people with mental illness. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198, 150–153.

Rush, A. J., Triveldi, M. H., Ibrahim, H. M., Carmody, T. J., Arnow, B., Klein, D. N., Markowitz, J. C., Ninan, P. T., Kornstein, S., Manber, R., Thase, M. E., Kocsis, J. H., & Keller, M. B. (2003). The 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Society of Biological Psychiatry, 54, 573–583.

Saklofske, D. H., Kelly, I. W., & Janzen, B. L. (1995). Neuroticism, depression, and depression proneness. Personality and Individual Differences, 18, 27–31.

Segerstrom, S. C., Tsao, J. C. I., Alden, L. E., & Craske, M. G. (2000). Worry and rumination: Repetitive thought as a concomitant and predictor of negative mood. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 671–688.

Shahar, B., Britton, W. B., Sbarra, D. A., Figueredo, A. J., & Bootzin, R. R. (2010). Mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Preliminary evidence from a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3, 402–418.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 372–386.

Takano, K., & Tanno, Y. (2009). Self-rumination, self-reflection, and depression: Self-rumination counteracts the adaptive effect of self-reflection. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 260–264.

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., Ridgeway, V. A., Soulsby, J. M., & Lau, M. A. (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 616–623.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259.

Verhaegen, P., Joormann, J., & Khan, R. (2005). Why we sing the blues: The relation between self-reflective rumination, mood, and creativity. Emotion, 5, 226–232.

Verplanken, B., Friborg, O., Wang, C. E., Trafimow, D., & Woolf, K. (2007). Mental habits: Metacognitive reflection on negative self-thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 526–541.

Watkins, E. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 163–206.

Watkins, E., Scott, J., Wingrove, J., Rimes, K., Bathurst, N., Steiner, H., Kenell-Webb, S., Moulds, M., & Malliaris, Y. (2007). Rumination-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for residual depression: A case series. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2144–2154.

Watson, D. (2000). Mood and temperament. New York: Guildford.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465–490.

Wells, K. B., Stewart, A., Hays, R. D., Burnam, M. A., Rogers, W., Daniels, M., Berry, S., Greenfield, S., & Ware, J. (1989). The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 262, 914–919.

Wells, K. B., Burnam, M. A., Rogers, W., Hays, R., & Camp, P. (1992). The course of depression in adult outpatients: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Archive of General Psychiatry, 49, 788–794.

Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Mindfulness, depression and modes of mind. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 721–733.

World Health Organization (2008). The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The contribution of Alleva was supported by NWO grant 404-10-118: Novel strategies to enhance body satisfaction.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alleva, J., Roelofs, J., Voncken, M. et al. On the Relation Between Mindfulness and Depressive Symptoms: Rumination as a Possible Mediator. Mindfulness 5, 72–79 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0153-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0153-y