Abstract

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is the first and most important vector-borne zoonotic disease transmitted by sand flies in Iran. As a parasitic disease in the Old World, it is a complex zoonosis with multiple vertebrate hosts and arthropod vectors of pathogenic flagellate protozoan in the genus of Leishmania in different parts of its range. Phlebotomine sand flies are proven as vectors of this parasite which can be transmitted through the bite of an infected female sand fly distributed in almost all parts of Iran. This research performed on all CL patients as that were registered into special forms by physicians and experts during the study period 2006–2013 in the county town of Fasa, Iran. Data were analyzed by Chi square test using SPSS 17 statistics software. Overall, 1,908 patients (59.18 %) lived in rural and 1,316 (40.82 %) lived in urban areas. All ages were between 1 and ≥30 year. The most frequent age group was ≥20 years (54.6 %). Sex ratio of patients was almost 1:1 (1,561; 48.42 % male vs. 1,663; 51.58 % female). Most of them (66.84 %) had wet lesions and those with dry lesions were less frequent (33.16 %). There was a significant difference between the frequencies of these two groups (P < 0.05). Hand ulcers were the most prevalent part of body (43.24 %). The highest prevalence rate (35.14 %) of lesions occurred in autumn. The unstable trend of this disease in different years and its relatively high disease burden affecting all age groups in Fasa with respect to other counties in Iran showed that it was most likely an endemic disease in this region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease due to a wide range of unicellular microparasites being transmitted by an even wider range of sand fly vectors infected with Leishmania (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) species. As a zoonosis with a wide variety of mammalian reservoir hosts including rodents, it occurs in at least three major cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral forms (Sacks 2001; Desjeux 2004).

Leishmaniasis is a cosmopolitan vector-borne disease affecting about 88 countries. It occurs in regions with warm temperate through subtropical to tropical climate (Ashford et al. 1992; Desjeux 1996). It is still one of the most problematic diseases in the world, affecting largely the poorest of the poor, mainly in developing countries of the Middle East (Molyneux 2004). About 2 million new cases are annually reported worldwide (World Health Organization 2010).

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL), after malaria, is the foremost important protozoan disease transmitted by sand flies in Iran (Moemenbellah-Fard et al. 2012). It occurs in two urban and rural forms with subtle disparity. The latter is a self-healing wet zoonotic CL (ZCL) caused by Leishmania (L.) major and chiefly transmitted by the sand fly Phlebotomus (Phlebotomus) papatasi from a rodent reservoir host to man (Azizi et al. 2012a, b, c). The urban dry form or anthroponotic CL (ACL) due to Leishmania (L.) tropica is mostly transmitted by the sand fly Phlebotomus (Paraphlebotomus) sergenti from an infected man (or a canine reservoir host) to a naive person.

Clinical manifestations of CL include a primary lesion at the site of insect bite which develops into a shallow ulcer with elevated edges. These lesions are usually discerned on nude areas of face and extremities. They may be accompanied with satellite lesions and local adenopathy. Self-healing of lesions may last several weeks to years and leads to flat atrophic scar.

Over 22,000 annual cases of CL are usually reported from the various parts of Iran where it should be noted that this is grossly underestimated (Yaghoobi-Ershadi et al. 2001). About 80 % of these cases are due to L. major parasites. More than half of the Iranian provinces have endemic foci of ACL and/or ZCL disease. The prevalence of CL in the endemic provinces of Khorasan, Fars, Isfahan, Yazd, Khuzestan and Kerman is high (Motazedian et al. 2002; Razmjou et al. 2009; Davami et al. 2010) and as such Ilam, Bushehr and Semnan have had high frequencies of cases in recent years. The incidence rate of cutaneous leishmaniasis has changed from 0.002 to 1.337 during the first decade of this century (Karimi et al. 2014). Northwest region of Iran, in contrast, has the lowest incidence of CL in the country.

CL prevalence is rising and new foci of disease transmission continue to emerge in Iran. To plan for disease control, comprehensive information about the effective factors in the disease epidemiology should be available, because this information will benefit and help in control programs. This study was thus conducted to investigate the epidemiological aspects of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Fasa county, Fars province, south of Iran.

Materials and methods

Study area

The present study was performed between April 2006 and April 2013 in healthcare centers of county town of Fasa with 53°40′E; 28°58′N coordinates and being 1,370 m above sea level. It is located in southeast of Fars province, south of Iran (Fig. 1). It has about 315,329 inhabitants living in an area of 4,188 km2. Fasa is a county town which lies 145 km to the southeast of Shiraz, the capital city of Fars province. The climate in this semiarid area covered mostly (93 %) by shrub lands is hot and humid with minimum and maximum temperatures of about 15 and 46 °C, respectively (average 30.3 °C). The relative humidity typically ranges from 11 % (dry) to 89 % (humid) over the course of the year. Wind speed varies from zero to 7 m/s annually. Most native people are engaged in agricultural activities.

Sampling and patients

This research was a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted over an eight-year study period in Fasa during which case definition remained constant. All the cases were identified as cutaneous lesishmaniases with wet or dry lesions. Both clinical and parasitological confirmations (lesion smear) were used to identify a case. All patients voluntarily consented to be examined for the cause of lesions. Prior to admission, an informed consent was obtained from each patient (aged >16 years) or the parents/guardians of each child examined. Sample size included all parasitological confirmed cases. All data were recorded in a few specific standardized forms. Patients’ information were collected by experienced staff which included such parameters as age, sex, job, place of residence, number, type, state and site of lesions, and season of disease transmission. The information was analyzed by Chi square test using SPSS 17.

Results

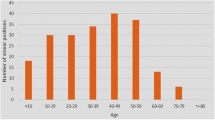

In this survey, a total of 3,224 individuals were diagnosed with both laboratory and clinical methods as cutaneous leishmaniasis patients. The sex ratio of patients was almost 1:1 (48.42 % males vs. 51.58 % females). Of these, 1,908 patients (59.18 %) lived in rural and 1316 (40.82 %) lived in urban areas (Table 1). All ages were grouped between 1 and ≥30 years. All age groups were, however, infected to varying degrees throughout each year. The abundance distribution of patients in their first three decades of life indicated that they were almost uniformly subjected to CL disease; each age-decade group had about the same quintile (i.e. ≈20 %) of patients. In contrast, some 1,134 (35 %) patients were in the age group of ≥30 years. There was a significant difference between the incidence of the disease in different age groups (P = 0.001). Most (62.5 %) of the patients were identified in the second half of the Iranian calendar year. The seasonal distribution of lesions indicated that patients were mostly referred to the local clinics during the colder months of the year (October–March).

Approximately, two-third of patients were diagnosed to have wet lesions characteristic of ZCL disease. There was a significant difference between the type of lesion and the incidence of disease (P = 0.041). No correlation was found between lesion type and sex or age (P > 0.05), but cases with wet lesions appeared to have multiple ulcers on their hands, feet or face. Most patients with wet lesions came from rural or suburban areas, while those with dry lesions mostly came from urban areas. A significant difference was also found between the frequencies of patients with wet type of CL lesion compared to those with dry type (P = 0.025). Most of these patients had only one (40 %), two (33.7 %), or three (22.9 %) lesions on their hands (43 %) compared with other categories of disease cases.

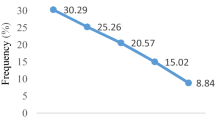

There was no clear delineation between patients in different occupational groups. Most (46.34 %) of them had miscellaneous occupations like driving, military activities, business etc. A clear majority (97.77 %) of disease cases had new active lesions, while only a negligible number (2.23 %) of cases showed scars after at least one year had elapsed from their initial inoculation with parasites by the sand fly vectors. On the other hand, the latter cases had already been treated. It was found that 36.23 % of patients had a history of travel to known endemic areas of leishmaniases. Some (7.26 %) of the infected cases had this disease within their family members. This infection showed an overall descending trend in the number of disease cases over the 8 year study period (Fig. 2). A clear majority (55.8 %) of patients were found in the first couple of years (2006-2007) of the study period.

Discussion

There was an overall reduction in the number of CL disease cases over an 8 year study period in the county town of Fasa, Fars province, southern Iran. It is, moreover, clear from the current study that about two-third of patients were identified to have wet lesions characteristic of ZCL disease. This finding was recently corroborated by a molecular report confirming the predominant distribution of L. major parasites in patients from this area (Sharafi et al. 2013). It is likely that the same strain of parasite was also isolated by molecular means from vector sand flies, P. (P.) papatasi (Parvin-Jahromi 2012), and possible rodent reservoir host, Tatera indica (Mehrabani et al. 2011). It remains, however, to be confirmed whether all these sympatric parasites were from the same or different genetic clusters infecting rodents, sand flies, and man (since no sequence analyses were done); a well-guarded statement could be that ZCL disease is prevalent in this area. Three different genetic clusters of L. major are known to occur in geographically distinct parts of Iran (Tashakori et al. 2011). The diverse pathogenic landscape of Iran seems to influence not only the distribution of reservoirs and vectors but also that of parasites with a low diversity of different genetic lineages (Parvizi et al. 2013).

In south and southeastern parts of Iran, where malaria is endemic (Moemenbellah-Fard et al. 2012), many vector control activities such as indoor residual spraying also lead to a reduction in transmission of ZCL disease cases. One key feature of the epidemiology of ZCL is the fact that it leads to lifelong protective immunity. In endemic areas, most native people get infected and become immune early in life; so any intervention to reduce transmission would ultimately result in a build-up of young non-immune individuals being susceptible to infection later in life. Any reduction of transmission would thus prepare the ground for an increase in ZCL disease burden and ages. Vector control is therefore not a reasonable option for the reduction of L. major parasites (Ashford 1999).

At least one-third of CL patients in this study suffered from dry ACL lesions emanating from L. tropica parasites. Most of these came from densely populated downhill urban and suburban areas where many risk factors such as brick wall type of housing alongside the presence of infected vectors, P. sergenti, contributed to the maintenance of a threshold community of human reservoir cases (Reithinger et al. 2010). There was thus a significant relationship between places of residence and incidence of disease. The asymptomatic patients from urban areas were exposed to the natural colonies of sand flies. Furthermore, upon travel to endemic areas, one could be exposed to sand fly bite as a result of which incidence of disease may upsurge (Desjeux 2001; Magill 2005). This finding has also been stated in previous reports (Nazari et al. 2012).

The results of this research confirmed that the incidence rate of disease in adult group (≥20) was the highest prevalence in CL (54.6 %) and incidence in children was lower than other age groups. This was in accordance with other previously-reported studies (Kassiri et al. 2012; Nazari et al. 2012). According to the present study, hand ulcers were the highest prevalent part of body (43.24 %). Since sand flies cannot bite human body through clothing due to their vestigial mouthparts, they are attracted to uncovered human skin such as hands and face where they can suck blood through relatively soft and delicate dermal areas. In endemic regions, this nuisance of sand fly bites could be exacerbated and/or misdiagnosed with those from other concomitant infectious vectors (Moemenbellah-Fard et al. 2014).

Finally personal protection is necessary to protect people against CL disease. Using diffusible repellents, case finding and treatment, vector control, animal reservoir control, insecticides impregnated bed nets, translocation of animal shelters and domestic animals to outdoors of human spaces and environmental modification can be effective for those in rural areas or individuals who work under field conditions (Maroli et al. 2013; Nateghi Rostami et al. 2013). Therefore this strategic approach in the fight against leishmaniasis should be considered in public health and educational programs for people. Media can raise the level of awareness of people on control of leishmaniasis too (Sarkari et al. 2014). In perspective, transmission modeling needs to be undertaken in such infectious disease systems to appreciate and elucidate better the dynamics of involved parameters (Parvizi et al. 2013).

References

Ashford RW (1999) Cutaneous leishmaniasis: strategies for prevention. Clin Dermatol 17:327–332

Ashford RW, Desjeux P, de Raadt P (1992) Estimation of population at risk of infection and numbers of cases of leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today 8:104–105

Azizi K, Abedi F, Moemenbellah-Fard MD (2012a) Identification and frequency distribution of Leishmania (L.) major infections in sand flies from a new endemic ZCL focus in southeast Iran. Parasitol Res 111:1821–1826

Azizi K, Moemenbellah-Fard MD, Kalantari M, Fakoorziba MR (2012b) Molecular detection of Leishmania major kDNA from wild rodents in a new focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in an oriental region of Iran. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis 12(10):844–850

Azizi K, Fakoorziba MR, Jalali M, Moemenbellah-Fard MD (2012c) First molecular detection of Leishmania major within naturally infected Phlebotomus salehi from a zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis focus in southern Iran. Trop Biomed 29:1–8

Davami MH, Motazedian MH, Sarkari B (2010) The changing profile of cutaneous leishmaniasis in a focus of the disease in Jahrom district, southern Iran. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 104:377–382

Desjeux P (1996) Leishmaniasis: public health aspects and control. Clin Dermatol 14:417–423

Desjeux P (2001) The increase in risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwide. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 95:239–243

Desjeux P (2004) Leishmaniasis: current situation and new perspectives. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 27:305–318

Karimi A, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Akhavan AA, Ghezelbash Z (2014) Spatial and temporal distributions of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae), vectors of leishmaniasis, in Iran. Acta Trop 132:131–139

Kassiri H, Sharifinia N, Jalilian M, Shemshad K (2012) Epidemiological aspects of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Ilam province, west of Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2(S1):S382–S386

Magill AJ (2005) Cutaneous leishmaniasis in the returning traveler. Infect Dis Clin North Am 19(1):241–266

Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charrel RN, Gradoni L (2013) Phlebotomine sand flies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med Vet Entomol 27:123–147

Mehrabani D, Motazedian MH, Hatam GR, Asgari Q, Owji SM, Oryan A (2011) Leishmania major in Tatera indica in Fasa, southern Iran: microscopy, culture, isoenzyme, PCR and morphologic study. Asian J Anim Vet Adv 6(3):255–264

Moemenbellah-Fard MD, Saleh V, Banafshi O, Dabaghmanesh T (2012) Malaria elimination trend from a hypo-endemic unstable active focus in southern Iran: predisposing climatic factors. Pathog Glob Health 106:358–365

Moemenbellah-Fard MD, Shahriari B, Azizi K, Fakoorziba MR, Mohammadi J, Amin M (2014) Faunal distribution of fleas and their blood-feeding preferences using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays from farm animals and human shelters in a new rural region of southern Iran. J Parasit Dis. doi:10.1007/s12639-014-0471-1

Molyneux DH (2004) “Neglected” diseases but unrecognized successes—challenges and opportunities for infectious disease control. Lancet 364:380–383

Motazedian MH, Noamanpoor B, Ardehali S (2002) Characterization of Leishmania parasites isolated from provinces of the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J 8:338–344

Nateghi Rostami M, Saghafipour A, Vesali E (2013) A newly emerged cutaneous leishmaniasis focus in central Iran. Int J Infect Dis 17:e1198–e1206

Nazari N, Faraji R, Vejdani M, Mekaeili A, Hamzavi Y (2012) The prevalence of cutaneous leishmaniases in patients referred to Kermanshah hygienic centers. Zahedan J Res Med Sci 14(8):77–79

Parvin-Jahromi H (2012) The faunestic study of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) and detection of vectors of cutaneous leishmaniasis using PCR in Fasa county, Fars province. M.Sc. thesis in medical entomology, School of Health, SUMS, Shiraz, Iran, 190 pp

Parvizi P, Alaeenovin E, Kazerooni PA, Ready PD (2013) Low diversity of Leishmania parasites in sand flies and the absence of the great gerbil in foci of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Fars province, southern Iran. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 107:356–362

Razmjou S, Hejazi H, Motazedian MH, Baghaei M, Emamy M, Kalantary M (2009) A new focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Shiraz, Iran. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 103:727–730

Reithinger R, Mohsen M, Leslie T (2010) Risk factors for anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis at the household level in Kabul, Afghanistan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4(3):e0000639

Sacks DL (2001) Leishmania-sand fly interactions controlling species-specific vector competence. Cell Microbiol 3(4):189–196

Sarkari B, Asgari Q, Shafaf MR (2014) Knowledge, attitude, and practices related to cutaneous leishmaniasis in an endemic focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis, southern Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 4(7):566–569

Sharafi M, Pezeshki B, Reisi A, Kalantari M, Naghizadeh MM, Dast-Manesh S (2013) Detection of cutaneous leishmaniasis by PCR in Fasa district in 2012. J Fasa Univ Med Sci 3(3):266–270

Tashakori M, Al-Jawabreh A, Kuhls K, Schönian G (2011) Multilocus microsatellite typing shows three different genetic clusters of Leishmania major in Iran. Microbes Infect 13(11):937–942

World Health Organization (2010) Report of a meeting of the WHO expert committee on the control of leishmaniases, Geneva. Tech Rep Ser 949:22–26

Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR et al (2001) Epidemiological study in a new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania major in Ardestan town, central Iran. Acta Trop 79:115–121

Acknowledgments

The present paper was extracted from the results of an approved M.Sc. student project (No: 90-3318 dated 12 July 2012) conducted by the first author, Mr. M. Khosravani. Thanks are due to the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology at SUMS, for permitting the use of facilities and financial support of this project at the university.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khosravani, M., Moemenbellah-Fard, M.D., Sharafi, M. et al. Epidemiologic profile of oriental sore caused by Leishmania parasites in a new endemic focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis, southern Iran. J Parasit Dis 40, 1077–1081 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-014-0637-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-014-0637-x