Abstract

Background/Objectives

Depression and hopelessness are frequently experienced in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and are generally associated with lessened physical activity. The aim of this study was to quantify the associations between sarcopenia as determined by SARC-F with both depression and hopelessness.

Design and Setting

This multicenter cohort study involving cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses was conducted in a university hospital and four general hospitals, each with a nephrology center, in Japan.

Participants

Participants consisted of 314 CKD patients (mean age 67.6), some of whom were receiving dialysis (228, 73%).

Measurements

The main exposures were depression, measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire, and hopelessness, measured using a recently developed 18-item health-related hope scale (HR-Hope). The outcomes were sarcopenia at baseline and one year after, measured using the SARC-F questionnaire. Logistic regression models were applied.

Results

The cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses included 314 and 180 patients, respectively. Eighty-nine (28.3%) patients experienced sarcopenia at baseline, and 44 (24.4%) had sarcopenia at the one-year follow-up. More hopelessness (per 10-point lower, adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.33, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.12–1.58), depression (AOR: 1.87, 95% CI 1.003–3.49), age (per 10-year higher, AOR: 1.70, 95% CI 1.29–2.25), being female (AOR: 2.67, 95% CI 1.43–4.98), and undergoing hemodialysis (AOR, 2.92; 95% CI, 1.41–6.05) were associated with a higher likelihood of having baseline sarcopenia. More hopelessness (per 10-point lower, AOR: 1.69, 95% CI 1.14–2.51) and depression (AOR: 4.64, 95% CI: 1.33–16.2) were associated with a higher likelihood of having sarcopenia after one year.

Conclusions

Among patients with different stages of CKD, both hopelessness and depression predicted sarcopenia. Provision of antidepressant therapies or goal-oriented educational programs to alleviate depression or hopelessness can be useful options to prevent sarcopenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sarcopenia is a muscle disorder characterized by low muscle quantity or quality and low muscle function, such as strength, and its secondary form can develop in advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) and dialysis as a result of aging or inflammatory processes observed in organ failure (1). Indeed, the prevalence of sarcopenia in CKD is significant. For example, the prevalence of sarcopenia determined by bio-impedance and handgrip strength is reported to be 5.9% in advanced CKD and 12.7% in hemodialysis (2, 3). Considering the prognostic impact of sarcopenia on mortality and/or hospitalization shown in these populations (3, 4), identifying modifiable risk factors for sarcopenia and developing preventive strategies is important. In addition to physical factors, psychological factors such as depression or hopelessness can be viewed as potential risk factors for sarcopenia, but they have been poorly investigated in both the general population and CKD.

That depression is correlated with sarcopenia was shown by a recent systematic review involving community and outpatient settings (5). In particular, one study involving elderly hemodialysis patients showed a strong association between depression and sarcopenia (6). Apart from depression, hopelessness is another psychological state that reflects a loss of value or future goals that is more likely to be experienced by patients with advanced CKD right before requiring dialysis and those receiving dialysis (7, 8). Although several studies suggest that persons experiencing hopelessness as well as depressive individuals are less likely to adhere to prescribed exercise (9, 10) and are less physically active (11), whether depression and hopelessness are independently associated with future sarcopenia in CKD remains unclear for two reasons. First, as acknowledged in the systematic review (5), only cross-sectional association between sarcopenia and depression was confirmed in the general population and CKD (5, 6) and second, disentangling hopelessness and depression has rarely been tested in the context of sarcopenia, probably because hopelessness may be regarded as a severe form of depression in the clinical setting (12). Clarifying the association of hopelessness and/or depression with future sarcopenia is clinically important as it may serve as a basis for the establishment of interventions to improve depression and hopelessness and effectively prevent sarcopenia.

Therefore, using data from the Hope Trajectory and Disease Outcome Consortium (HOTDOC) study, a multicenter cohort study was conducted to examine the associations between hopelessness and depression with the prevalence and incidence of sarcopenia among patients with advanced CKD and dialysis.

Methods

Setting and participants

The HOTDOC study was a multicenter cohort study conducted at a university hospital and four general hospitals, each of which had a nephrology center. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of St. Marianna University (Number 3209) and Fukushima Medical University (Number 2417). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. All of the participants were adults (mean age 67.6) with CKD who were being treated by nephrologists at the participating centers. Some did not require dialysis, while others were receiving hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Those with a psychiatric condition that could impair their ability to understand or respond to verbal or written instructions (e.g., advanced dementia, schizophrenia, intellectual disability) were not included.

Main exposures

The main exposures were depression and hopelessness. Depression was measured using the Japanese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (13). The CES-D includes 20 items with each item being rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, with 1 meaning “less than 1 day” (0 points) and 4 meaning “5–7 days” (3 points). The coefficient alpha was 0.84 (14). A total score of 16 or higher was considered to indicate depression (15). Hopelessness was measured using the health-related hope scale (HR-Hope). It measures hope among people with chronic diseases (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) (14). The HR-Hope includes 18 items with each item being rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale. Respondents are instructed to «Please answer the questions below while keeping in mind how you feel about your future health prospects.» The respondents score each item on a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 meaning “I don’t feel that way at all” and 4 meaning “I strongly feel that way.” For this study, the mean score of all 18 items was computed. For patients without family, the two items related to family were not applicable; thus, the scale score was computed as the mean of the remaining 16 items. Next, the mean score was transformed to a score between 0 and 100. Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.93. Scores on the HR-Hope scale were moderately correlated with scores on both domains of the Snyder hope scale (16). In addition, the HR-Hope scale was more sensitive to changes in socio-clinical status than the Snyder hope scale (14).

Outcomes

The main outcome was sarcopenia, measured by SARC-F as used in other studies (17). SARC-F is a self-report questionnaire and comprises five items — strength, assistance walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls—with responses for each item ranging from 0 to 2 points (Supplementary Table S3). A total score of 4 or higher is considered to indicate probable sarcopenia (17, 18). Use of SARC-F is recommended by working groups such as the European Working Group on Sarcopenia Older Persons and the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia to screen for sarcopenia (1, 19). SARC-F has a high ability to diagnose sarcopenia (specificity = 90–94 %) (20). In this study, a validated Japanese version of SARC-F was used (21).

For the cross-sectional analysis, the identified outcome was the prevalence of sarcopenia. The incidence of sarcopenia one year after the baseline survey was considered the outcome in the longitudinal study.

Covariates

Confounding variables were those suspected of being associated with both HR-Hope and sarcopenia based on evidence from the literature and clinical expertise. These variables included age, sex, diabetic nephropathy as the primary renal disease, body mass index (BMI), treatment status (nondialyzed, peritoneal dialysis, or hemodialysis), comorbidities (such as cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and malignancy), working status as a proxy for socioeconomic status, presence of family as a proxy for loneliness, and depression. Working status was determined by asking, «During the past 4 weeks, did you work at a paying job?» to which the patients answered “yes” or “no.” Presence of family was determined by asking, «Do you have any family?» to which participants could respond “yes” or “no”.

Data collection

Participants were patients registered between February 2016 and September 2017, and questionnaire surveys were conducted three times: during the registration period and then one and two years later. For this study, second and third questionnaire survey data were used as data on sarcopenia and were collected on those two occasions. The questionnaire was administered at each participating center, and the patients were asked to complete it at home. If the patients could not write due to visual impairment or physical disability, they were asked to verbally complete the form with the aid of a trained research assistant who did not inform them of the hypothesis.

Data on demographic factors, primary renal disease, BMI, and comorbidities, except for age and dialysis duration (only for patients receiving hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis), were extracted from medical records during the first questionnaire survey. Data on age and dialysis duration were based on the second questionnaire survey.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/SE, version 15 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). Baseline characteristics were summarized as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. A histogram was graphed for the HR-Hope scores. The distribution of sarcopenia at baseline by quartile-defined categories of HR-Hope scores was graphed. Trends across those categories of HR-Hope scores were analyzed using a non-parametric trend test for sarcopenia at baseline.

The associations of HR-Hope with sarcopenia at baseline were analyzed using logistic regression to estimate the adjusted odds ratio (AOR). Age, sex, diabetic nephropathy, BMI, treatment status, comorbidities, working status, presence of family, and depression were entered into the multivariate analyses as covariates. Subsequently, the association of HR-Hope with sarcopenia at the one-year follow-up was analyzed using logistic regression models. The covariates included those used for the cross-sectional analysis and sarcopenia determined at baseline. Data were addressed by a multiple imputation approach to generate five imputed datasets using chained equations methods, assuming that the analyzed data were missing at random (22, 23). To derive effect estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from the multiple imputed data, the mean for each of the five estimates for coefficients of each model was determined, and variances of the five estimates were pooled according to Rubin’s rules (24).

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

Among 321 participants, 314 were included in the cross-sectional analysis; seven were excluded due to incomplete or missing responses to the HR-Hope or SARC-F (Supplementary Figure S1). The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 67.6, and 102 (23%) of the patients were women. The mean HR-Hope score was 59.5 (standard deviation [SD]: 18.8). HR-Hope scores were normally distributed (Figure 1). Eighty-nine patients experienced sarcopenia at baseline, with a prevalence of 28.3%.

Associations of hopelessness and depression with prevalent sarcopenia

Figure 2 shows the distribution of prevalent sarcopenia, by quartile-defined categories of HR-Hope scores. Prevalence of sarcopenia was higher among participants with lower HR-Hope scores (p = 0.016). This association was unchanged after adjustment for likely confounders (adjusted OR per ten-point lower 1.33, 95% CI 1.12–1.58 for prevalent sarcopenia, Table 2). Participants with depression had more prevalent sarcopenia than those without depression, independently of HR-Hope score (adjusted OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.003–3.49). The older the participant, the higher the prevalence of sarcopenia (adjusted OR per ten-year difference 1.70, 95% CI 1.29–2.25). Women had more prevalent sarcopenia than men (adjusted OR 2.67, 95% CI 1.43–4.98). Participants who had been receiving hemodialysis had more prevalent sarcopenia than did participants who did not require dialysis (adjusted OR 2.92, 95% CI 1.41–6.05). Participants with cerebrovascular disease had a higher prevalence of sarcopenia than participants without cerebrovascular disease (adjusted OR 2.64, 95% CI 1.14–6.09).

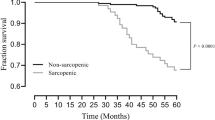

Associations of hopelessness and depression with sarcopenia at one year

Of the patients included in the cross-sectional analysis (n = 314), 134 did not participate in the follow-up survey because of death (n = 23), referral to other facilities (n = 14), change in treatment modality (n = 5), hospitalization during the one-year follow-up survey (n = 2), or unknown reasons (n = 90). Therefore, 180 patients were included in the longitudinal analysis. Except for treatment modality, baseline characteristics were similar between those who completed the follow-up survey and those who did not (Supplementary Table S4). Those who completed the follow-up were more likely to be on hemodialysis. Forty-four (24.4%) patients had sarcopenia at the one-year follow-up. In the logistic regression model adjusted for covariates including baseline sarcopenia, participants with lower HR-Hope scores at baseline were more likely to have sarcopenia at one year (adjusted OR per ten-points lower 1.91, 95% CI 1.32–2.76, adjusted model 1 in Table 3). After additional adjustment for depression, this association was unchanged (adjusted OR per ten-points lower 1.69, 95% CI 1.14–2.51, adjusted model 2 in Table 3). Independent of the HR-Hope score, participants with depression at baseline were more likely to have sarcopenia at one year than those without depression at baseline (adjusted OR 4.64, 95% CI 1.33–16.2).

Discussion

We found that both depression and hopelessness were associated with sarcopenia at baseline and one year later among patients with advanced CKD and dialysis. These findings highlight the importance of integrating consideration of psychological aspects into clinical practice throughout the different stages of CKD to prevent sarcopenia.

Our findings regarding the association between depression and sarcopenia align well with those of previous studies conducted among elderly hemodialysis patients and the general population (5, 6). However, our study differs in several aspects. First, although previous studies have shown cross-sectional associations of sarcopenia with depression (5, 6), our study was additionally able to show the prediction of one-year sarcopenia by depression and directly addressed the call for validating the causal relationship between depression and sarcopenia noted in a systematic review study (5). Our findings support the presence of a pathogenic pathway in which depression might directly cause sarcopenia, at least in patients with advanced CKD and dialysis. Second, an independent association of hopelessness with sarcopenia has not previously been examined. Therefore, our findings provide evidence of a novel pathogenic pathway in which sarcopenia develops in nephrology settings. Such an association independent of depression suggests that hopelessness is an entity distinct from depression (11) with consequences distinct from those associated with depression (25). This notion is potentially important because hopelessness can be observed in the absence of depression (11), and the notion is further supported by findings of previous research showing the predictive role of hopelessness on the development of cardiovascular risks such as hypertension and myocardial infarction is independent of depression (25, 26). A number of explanations are possible for the predictive association between hopelessness and sarcopenia: as was shown in the general population, hopelessness may increase levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) (12), and low-grade inflammation in turn leads to protein degradation and muscle wasting that is observed in advanced CKD and dialysis (6, 27). Hopeless or depressive patients are less likely to adhere to prescribed exercise (9) and less likely to engage in physical activities even during leisure time (11). Additionally, given that the HR-Hope scale to measure hopelessness probes patients’ prospects for adjusting their personal health goals or developing personal lifestyle strategies to deal with their actual disease condition (14), patients with hopelessness as measured by the scale may cope poorly with their kidney disease.

We believe that the present findings may influence the activities of nephrology physicians and co-medical staff for several reasons. Both depression and hopelessness are potentially modifiable factors that can prevent sarcopenia. First, antidepressant therapies such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (sertraline) and cognitive behavioral therapy have been shown to reduce depressive symptoms even in dialysis (28). However, patients’ acceptance of these therapies is not always satisfactory (28), and the efficacy of sertraline is inconsistent (29). Further studies are warranted to determine whether long-term antidepressant therapies result in improvement in depressive symptoms and prevention of sarcopenia. Second, an education program to foster hope is a possible way to enhance self-management for the prevention of sarcopenia, as has been suggested in the field of management of musculoskeletal disorders (30). Specifically, nephrology physicians and co-medical staff can communicate with their patients about how their purpose in life (which can be captured using the “something to live for” domain items in the HR-Hope scale) or daily functioning is interrupted by CKD or its treatment. Thus, clinicians can encourage patients to think about what they believe to be personally important among the interrupted things they listed and to set realistic and achievable goals (31). If clinicians suggest specific exercise programs or nutritional regimens, patients can choose the suggestions and incorporate and maintain some specific strategies to achieve their goals. Maintenance of such strategies would ultimately result in preservation of muscle mass and function and prevent sarcopenia. Indeed, in studies of patients with chronic back pain, patient-led goal setting and education intervention were shown to be efficacious in reducing disability and pain (31). Third, our findings on characteristics associated with sarcopenia can be used to identify cases of sarcopenia among patients with advanced CKD and dialysis. Not only well-known risk factors for sarcopenia, such as being older, being female, and having cerebrovascular disease, but also conditions requiring hemodialysis should receive more attention for several reasons. Compared to peritoneal dialysis, there are more patients who have difficulty in receiving dialysis therapy on its own; in addition, protein loss and rapid fluid removal during hemodialysis result in muscle waiting and fatigue. Therefore, more frequent screening for sarcopenia may be required for hemodialysis patients than commonly thought.

This study has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first cohort study showing independent associations of sarcopenia with depression and hopelessness among patients with different stages of CKD (i.e., those with advanced CKD and those requiring dialysis) with adjustment for potential confounding variables. Second, the multicenter design increases the generalizability of our findings to other Japanese facilities.

Several limitations of the study warrant mention. First, the definition of sarcopenia in this study was based on the SARC-F questionnaire. Although SARC-F has high specificity for diagnosing sarcopenia, its sensitivity is admittedly low (1, 20). However, SARC-F has a higher sensitivity for diagnosing severe sarcopenia, as determined by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia’s 2019 update (19), and is useful for detecting low handgrip strength and low gait speed among hemodialysis patients (32). Second, the definition of depression was based on a self-reported scale (i.e., CES-D) rather than a structured clinical interview. However, the CES-D scale was validated against a structured clinical interview method for diagnosing depression among hemodialysis patients (33). Third, hopelessness as measured by the HR-Hope scale may be affected by spiritual and religious factors. However, we believe that any effects of spiritual or religious factors on the associations found in this study are insignificant, as all study participants were Japanese, among whom few regularly engaged in personal religious activities (34). Fourth, the number of patients not included in the longitudinal study for unknown reasons (n = 90) was not negligible. This might limit the applicability of the associations reported in the present study. Patients who could not participate in the follow-up survey were less likely to be on dialysis than those who could participate, although other baseline characteristics did not differ among them (Supplementary Table S4). Further study including a large sample of CKD patients would be warranted to validate the present findings. Fifth, data on some potential predictors of sarcopenia, such as detailed nutritional or socioeconomic measures, were not collected. However, we adjusted for BMI and working status as proxies for nutrition status and socioeconomic status, respectively. Thus, the association of depression with sarcopenia or hopelessness with sarcopenia is not likely to be confounded by nutritional or socioeconomic status. In addition, the use of BMI collected one year prior to baseline may have contributed to the misclassification of BMI.

Conclusion

Depression as well as hopelessness as captured by the HR-Hope scale were associated with a higher likelihood of having sarcopenia at baseline and after one year. In addition, patients receiving hemodialysis were associated with a higher likelihood of having sarcopenia at baseline than those with CKD not requiring dialysis. Careful attention to patients with vulnerable characteristics and the development of cognitive behavioral therapy or goal-oriented educational programs to alleviate depression or hopelessness are critical for preventing sarcopenia among patients with CKD.

References

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyere O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019;48(1):16–31.

Lamarca F, Carrero JJ, Rodrigues JC, Bigogno FG, Fetter RL, Avesani CM. Prevalence of sarcopenia in elderly maintenance hemodialysis patients: the impact of different diagnostic criteria. J Nutr Health Aging 2014;18(7):710–7.

Pereira RA, Cordeiro AC, Avesani CM, Carrero JJ, Lindholm B, Amparo FC, et al. Sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease on conservative therapy: prevalence and association with mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015;30(10):1718–25.

Giglio J, Kamimura MA, Lamarca F, Rodrigues J, Santin F, Avesani CM. Association of sarcopenia with nutritional parameters, quality of life, hospitalization, and mortality rates of elderly patients on hemodialysis. J Ren Nutr 2018;28(3):197–207.

Chang KV, Hsu TH, Wu WT, Huang KC, Han DS. Is sarcopenia associated with depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Age Ageing 2017;46(5):738–46.

Kim JK, Choi SR, Choi MJ, Kim SG, Lee YK, Noh JW, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with sarcopenia in elderly patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin Nutr 2014;33(1):64–8.

Kurita N, Wakita T, Ishibashi Y, Fujimoto S, Yazawa M, Suzuki T, et al. Association between health-related hope and adherence to prescribed treatment in CKD patients: multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 2020;21(1):453. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-02120-0

Billington E, Simpson J, Unwin J, Bray D, Giles D. Does hope predict adjustment to end-stage renal failure and consequent dialysis? Br J Health Psychol 2008;13(4):683–99.

Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, Romanelli J, Richter DP, Bush DE. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2000;160(12):1818–23.

Blumenthal JA, Williams RS, Wallace AG, Williams RB, Jr., Needles TL. Physiological and psychological variables predict compliance to prescribed exercise therapy in patients recovering from myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med 1982;44(6):519–27.

Valtonen M, Laaksonen DE, Laukkanen J, Tolmunen T, Rauramaa R, Viinamäki H, et al. Leisure-time physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness and feelings of hopelessness in men. BMC Public Health 2009;9(1):204.

Mitchell AM, Pössel P, Sjögren E, Kristenson M. Hopelessness the “active ingredient”? Associations of hopelessness and depressive symptoms with interleukin-6. Int J Psychiatr Med 2013;46(1):109–17.

Shima S, Shikano T, Kitamura T, Asai M. New self-rating scale for depression. Clin Psychiatry 1985;27(6):717–23 (in Japanese).

Fukuhara S, Kurita N, Wakita T, Green J, Shibagaki Y. A scale for measuring health-related hope: its development and psychometric testing. Ann Clin Epidemiol 2019;1(3):102–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.37737/ace.1.3_102

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1(3):385–401.

Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, et al. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991;60(4):570–85.

Merchant RA, Chen MZ, Wong BLL, Ng SE, Shirooka H, Lim JY, et al. Relationship between fear of falling, fear-related activity restriction, frailty, and sarcopenia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020:68(11):2602–8.

Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. SARC-F: a simple questionnaire to rapidly diagnose sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14(8):531–2.

Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020; 21(3): 300–7.e302.

Ida S, Kaneko R, Murata K. SARC-F for screening of sarcopenia among older adults: A meta-analysis of screening test accuracy. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19(8):685–9.

Kurita N, Wakita T, Kamitani T, Wada O, Mizuno K. SARC-F validation and SARC-F+EBM derivation in musculoskeletal disease: the SPSS-OK study. J Nutr Health Aging 2019;23(8):732–8.

van der Heijden GJMG, Donders AR, Stijnen T, Moons KG. Imputation of missing values is superior to complete case analysis and the missing-indicator method in multivariable diagnostic research: A clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59(10):1102–9.

van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med 1999;18(6):681–94.

Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for non response in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987.

Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Salonen JT. Hypertension incidence is predicted by high levels of hopelessness in Finnish men. Hypertension 2000;35(2):561–7.

Everson SA, Goldberg DE, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Pukkala E, Tuomilehto J, et al. Hopelessness and risk of mortality and incidence of myocardial infarction and cancer. Psychosom Med 1996;58(2):113–21.

Honda H, Qureshi AR, Axelsson J, Heimburger O, Suliman ME, Barany P, et al. Obese sarcopenia in patients with end-stage renal disease is associated with inflammation and increased mortality. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86(3):633–8.

Mehrotra R, Cukor D, Unruh M, Rue T, Heagerty P, Cohen SD, et al. Comparative efficacy of therapies for treatment of depression for patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 2019;170(6):369–79.

Hedayati SS, Gregg LP, Carmody T, Jain N, Toups M, Rush AJ, et al. Effect of sertraline on depressive symptoms in patients with chronic kidney disease without dialysis dependence: the CAST randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318(19):1876–90.

Veres A, Bain L, Tin D, Thorne C, Ginsburg LR. The neglected importance of hope in self-management programs—a call for action. Chronic Illn 2014;10(2):77–80.

Gardner T, Refshauge K, McAuley J, Hübscher M, Goodall S, Smith L. Combined education and patient-led goal setting intervention reduced chronic low back pain disability and intensity at 12 months: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2019;53(22):1424–31

Marini ACB, Perez DRS, Fleuri JA, Pimentel GD. SARC-F is better correlated with muscle function indicators than muscle mass in older hemodialysis patients. J Nutr Health Aging 2020;24(9):999–1002.

Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Kuchibhatla M, Kimmel PL, Szczech LA. The predictive value of self-report scales compared with physician diagnosis of depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2006;69(9):1662–8.

Roemer M. Religious affiliation in contemporary Japan: untangling the enigma. Rev Relig Res 2009;50(3):298–320.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly thank the following researchers, research assistants, and medical staff members for their assistance in collecting the questionnaire-based and clinical information used in this study: Ms. Asako Tamura, Ms. Yuka Masuda, and Ms. Takae Shimizu (St. Marriana University, Kawasaki-City, Kanagawa); Takayuki Nakamura, MD and Eiko Hashimoto, RN (JCHO Nihonmatsu Hospital, Nihonmatsu-City, Fukushima); Atsushi Kyan, MD and Masashi Saito, CE (Shirakawa Kosei General Hospital, Shirakawa-City, Fukushima); Ms. Lisa Shimokawa and Ms. Miyuki Sato (Fukushima Medical University Hospital, Fukushima-City, Fukushima).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributions: Research idea and study design: NK, TW, YS, YI; data acquisition: NK, YI, SF, M Yazawa, TS, KK, M Yanagi, HK; data analysis and interpretation: NK, TW, YS, YI; statistical analysis: NK; supervision or mentorship: YS, YI. Each author contributed important intellectual content during article drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Ethical Standards: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical guidelines for Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects in Japan.

Additional information

Financial Disclosure: This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number: JP16H05216 and JP18K17970).

Sponsor’s role: The funder had no role in the study design, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Impact Statement: We certify that this work is a novel clinical research contribution. We believe that its novelty and impact lie in the fact that existing literature has not investigated the predictive aspect of hopelessness for sarcopenia, differentiating it from depression amongst CKD and dialysis patients. The findings will allow clinicians and caregivers to create interventions that alleviate depression and hopelessness among CKD and dialysis patients, thus preventing sarcopenia.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kurita, N., Wakita, T., Fujimoto, S. et al. Hopelessness and Depression Predict Sarcopenia in Advanced CKD and Dialysis: A Multicenter Cohort Study. J Nutr Health Aging 25, 593–599 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1556-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1556-4