Abstract

Ending hunger and alleviating poverty are key goals for a sustainable future. Food security is a constant challenge for agrarian communities in low-income countries, especially in Madagascar. We investigated agricultural practices, household characteristics, and food security in northeast Madagascar. We tested whether agricultural practices, demographics, and socioeconomics in rural populations were related to food security. Over 70% of respondents reported times during the last three years during which food for the household was insufficient, and the most frequently reported cause was small land size (57%). The probability of food insecurity decreased with increasing vanilla yield, rice yield, and land size. There was an interaction effect between land size and household size; larger families with smaller land holdings had higher food insecurity, while larger families with larger land had lower food insecurity. Other socioeconomic and agricultural variables were not significantly related to food insecurity, including material wealth, education, crop diversity, and livestock ownership. Our results highlight the high levels of food insecurity in these communities and point to interventions that would alleviate food stress. In particular, because current crop and livestock diversity were low, agricultural diversification could improve outputs and mitigate food insecurity. Development of sustainable agricultural intensification, including improving rice and vanilla cultivation to raise yields on small land areas, would likely have positive impacts on food security and alleviating poverty. Increasing market access and off-farm income, as well as improving policies related to land tenure could also play valuable roles in mitigating challenges in food security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Food insecurity, malnutrition, and environmental degradation are global challenges facing low- and middle-income countries, especially in the tropics (Schipanski et al., 2016). Over 800 million people were undernourished in 2017, and 1/3 were from sub-Saharan Africa (UNDP, 2020). Food insecurity and malnutrition disproportionately affect women and children, making them a high-risk population, and increases the risk of infection with other diseases globally (FAO et al., 2020). Simultaneously, unsustainable farming practices are reducing agricultural output (Messerli, 2000, 2006; Styger et al., 2007), and causing the loss of natural habitats, species extinctions, and the deterioration of ecosystem services (Powers & Jetz, 2019). Therefore, achieving the sustainable development goals requires transdisciplinary research and outreach at the nexus of health, agriculture, and conservation.

Madagascar exemplifies many of the challenges facing tropical low-income countries. Marked inequality exists in both health and economic opportunities. Approximately 40% of women are anemic, and 50% of children are malnourished (FAO, 2020; Golden et al., 2011; Golden et al., 2020). Farmers face challenges of food security from many causes, including extreme weather patterns (Harvey et al., 2014). Variation in relative wealth can have large impacts on natural resource use and participation in agricultural markets. Farmers with larger land holdings and family labor were able to invest more in land use intensification and participation in cash crop markets than other farmers, which reduced their need to clear new land for agriculture (Laney & Turner, 2015). Women tend to own less land and have fewer rights to land than men, and households with a single female head may be at a significant disadvantage in terms of economics and access to agricultural land (Widman, 2014). Education is also an important factor in sustainable development and remains a challenge for rural communities, where a primary school education can be difficult to obtain (Harvey et al., 2014). All these socioeconomic factors put farmers in Madagascar at high risk for food insecurity and point to the potential for inequalities, especially among genders.

The agricultural sector is inextricably tied to socioeconomic characteristics and food security. In Madagascar, 64% of the population were employed in agriculture in 2019 (World Bank and ILOSTAT, accessed June 2020). Subsistence agriculture is the only livelihood for most people in the rural countryside. Unsustainable farming practices, especially shifting agriculture on steep slopes with short fallow periods, put pressure on natural resources and biodiverse hotspots (Borgerson et al., 2018; Borgerson et al., 2019; Golden et al., 2011; Laney & Turner, 2015; Messerli, 2006; Styger et al., 2007). Crop yields are decreasing due to declining soil health, and traditional methods are becoming less productive (Harvey et al., 2014; Laney & Turner, 2015; Messerli, 2006; Styger et al., 2007; Styger et al., 2009). Malagasy farmers typically rely on three main food crops: rice, maize, and cassava (Harvey et al., 2014). Further, low yields in staple crops, especially rice, often do not sustain households throughout the year. Methods of agriculture that sustainably increase yields and regenerate degraded lands have not had widespread adoption in Madagascar, such as improved rice agriculture (Jones et al., 2021; Stoop et al., 2002) and agroforestry (Messerli, 2006; Rosenstock et al., 2019). Agricultural productivity is clearly an important factor to understanding smallholder farmer food security. We investigated how this constellation of agricultural factors affects farmer food security.

Cash crops can generate income to help lift households out of relative poverty. In the SAVA region of northeast Madagascar, 50–65% of the world’s vanilla is cultivated by approximately 70,000 smallholder farmers in the foothills of biodiverse rainforests (percentages based on OEC data between the years 2000–2017, Brown, 2009; Hänke et al., 2018; Hending et al., 2019; Laney & Turner, 2015). Generating over 800 million USD annually in international exports in 2017 (OEC data accessed 2020), this single cash crop creates economic opportunities that can alleviate poverty and food insecurity by having cash income to buy food in addition to their subsistence agriculture (Laney & Turner, 2015). Therefore, higher yields of this and other cash crops may improve food security in this system because farmers will have a valuable product with which to earn income or barter to supplement subsistence production. Vanilla agriculture is, however, labor intensive and requires specialized knowledge (Hänke et al., 2018; Laney & Turner, 2015). Further, there are heterogeneities among farmers in the degree of economic benefits from vanilla cultivation, such that some farmers have high productivity and income, while a large proportion have a relatively low yield and income-earning potential (Hänke et al., 2018; Martin, Wurz, et al., 2020a, Martin, Osen, et al., 2020b). Extreme weather events, like cyclones, have the potential to devastate crops (Brown, 2009), and theft is a growing problem (Neimark et al., 2019). The value of vanilla on the international market is also subject to extreme volatility, making income at the farm gate highly unpredictable (Hänke et al., 2018). Vanilla agriculture therefore has a high potential for income generation, but is not without its potential drawbacks in terms of market volatility and socio-cultural consequences.

The solutions to these problems require interdisciplinary research and policy reform for sustainable development (Jones et al., 2019). We conducted research on food security, agricultural practices, and household characteristics in the SAVA region of Madagascar. Our goal was to understand how agricultural productivity, demographics, household assets, and other factors affect food insecurity among smallholder farmers. Our research at the intersection of food security, agriculture, and natural resource management has important applications for conservation policy in relation to land use.

Thus, the aim of our work was to understand the relationships between food security, agricultural practices and socioeconomics in rural communities around the SAVA region. We tested hypothesized effects of agricultural practices and household characteristics on food insecurity as follows (Fig. 1).

-

1)

Agricultural factors: food insecurity decreases with increasing land size, the diversity of food and cash crops as well as livestock, and the yield of rice and vanilla.

-

2)

Socioeconomic factors: Food insecurity increases with the number of people in the household, lower wealth, and is higher for households with single female heads, compared to households with male heads or pairs living together. Food insecurity decreases with higher education level.

2 Materials and methods

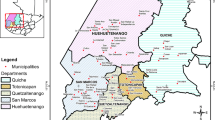

We conducted this study in three communities: Manantenina, Mandena, and Matsobe (Fig. 2).

Map of survey villages in the northeast SAVA region of Madagascar. Study villages are shown in blue, and one of the major cities in the region, Andapa, is labelled with a triangle. The other major city nearby, Sambava, is off the map to the east. The Marojejy National Park boundary is also shown. The tree cover (>50% canopy closure of trees >5 m height), as of the year 2010, and the forest loss between the years 2000 and 2018 are shown at 30 m resolution, based on the data from Hansen et al. (2013). The inset shows the SAVA region

Study design

The survey team included RJY and NAFR as the primary enumerators, local Malagasy researchers from each village, and AO, CF, and MM. Data were collected during the months of June and August, in Mandena in 2018, and in Manantenina and Matsobe in 2019. In each of the three communities, we conducted social surveys for randomly selected households. In Mandena, a drone image of the village was overlaid with a grid system (100X100m cells), which was used to first randomly sample grids, and then randomly sample households within grids, in proportion to the number of houses in those grids. In Manantenina, a member of the research team who lived in the village provided a complete list of all village households, which was used to randomly sample households. In Matsobe, 2018–2019 census data were used to randomly select households. If no members of the randomly selected household could be found, that household was substituted for an available neighbor.

All surveys were administered in the local dialect of Malagasy, and informed consent was given by all study participants prior to taking the survey. RJY or AFR and/or a local research team member, fluent in the local dialect, conducted the informed consent and survey with the study participant. The survey was conducted using Qualtrics software on Samsung tablets, and had an average duration of 60 min to complete. Study participants were compensated with 1000 Ariary (MGA, approximately 0.30 USD) in mobile phone credit upon survey completion.

Food insecurity

Questions about food insecurity were modified from a prior study of agrarian socioeconomics in Malawi (Ward et al., 2018). We asked respondents if they had times when there was not enough food to feed the family over the past three years. We note that in Malagasy culture, when referring to food security generally, the interpretation is whether there was enough rice for the household, since rice is the staple food. To address the causes of food insecurity, options on the survey included small land size, lack of money, the cost of food in the local markets, extreme natural events (i.e., cyclones, droughts, insect or rodent pest outbreaks), as well as allowing the respondent to give any other reason for food insecurity.

Socioeconomic characteristics

Standard data on demographics of households were collected using a survey adapted from the Demographic and Health Survey instrument (ICF International, 2012). These variables included the number of individuals in the household, their ages in years, gender, education level, and main activity (farming, wage labor, etc.), and whether farmers reported other wage-earning activities other than their subsistence farming. To assess material wealth, we also collected data on the ownership of common household assets, such as radio, television, telephone, generator, solar panels, and farming tools including shovels, axes, plows. We asked about the household materials used to build the walls, roof, and floor, including natural products that were collected such as bamboo, raffia, and Ravinala, and purchased materials including wood planks, aluminum sheets, or cement. To create composite asset indicators, we used principal components analysis (PCA) to summarize the data on household assets and household building materials into orthogonal axes that best captured the variance in the data (Appendix Table 1). As an alternative measure, we summed the number of assets the respondent reported. Households were classified as having a single female head if the respondent was female, identified herself as the head of the household, and reported that she was either not married nor living with a partner, or was a widow.

Agricultural practices

Questions about agricultural practices included the types of crops grown, how farmers grew rice (low-land flooded paddies, on hillsides, or both), and domestic animal ownership (the number of animals owned for livestock, poultry, and other animals, enumerated between 1 and 5 or more than 5 individual animals). The size of farm land was assessed by asking farmers about the input of rice that would be required to grow rice on their land, based on a conversion that approximately 15 kg is used to farm one ha (pers. comm. with local stakeholders). Rice and vanilla harvests were calculated in kg.

To calculate crop diversification, we enumerated the total number of crops the farmers reported growing in the last year, as well as the total number of cash crops (coffee, cloves, cacao, and vanilla). We also calculated the proportion of the top five crops grown by the respondent, based on the five most commonly grown crops across all respondents. We divided these proportions among the top five food and cash crops. Lastly, we used a PCA to summarize the crop data into two axes that best separated farmers according to those that grow similar crops (Appendix Table 2). We quantified variation in domestic animal ownership as the sum of domestic animals owned, as well as the richness and diversity (Shannon diversity index) of all domestic animals owned (cattle, pigs, goats, poultry). We also conducted a PCA of domestic animals owned to use the first PC as a composite score of domestic animal ownership (Appendix Table 3).

Analyses

All data were examined for outliers that were due to errors, and in general log transformations were applied to the data to approximate normal distributions and reduce the influence of extreme values. We used generalized linear models to test whether food insecurity (binary variable) was predicted by livestock and crop diversity, rice and vanilla harvests, land size, the material asset scores, education, whether the head of the household was a single female or not, and household size. All continuous variables were standardized before analyses (z-score transformation). We tested for interactions between significant variables when plotting the results suggested that an interaction effect may be present. We included the village identity as a fixed effect. We used the “dredge” function in the R package MuMIn (Bartoń, 2013) to compare models of all combinations of the variables listed above to determine the candidate set that best fit the data based on the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) score. The initial model included the variables listed above, as well as interactions of land size with household size, and vanilla yields with rice yields. Model averaging was then used to determine the size of the effect of each independent variable on food insecurity, weighting by the AIC weight. All models were evaluated for the fit of the data to the model, and violations of assumptions by testing for outliers, ensuring predictor variables were not multicollinear via intercorrelations < |0.50|, examining the distribution of residuals, and goodness of fit tests.

3 Results

Our sample included over 350 people in three villages (Table 1). In education, 49% of respondents had a primary school education, 8% had no formal school education, and less than half had higher education. Male respondents had a higher likelihood of a higher than secondary school education than female respondents (chi-square, adjusted p for pairwise comparisons = 0.03), but otherwise there were no differences between genders in education levels. Thirty-one percent of households had a single female head (either never married, separated, or widowed). Significantly more people obtained their water from rivers and streams than piped water or wells (73%, chi-square = 256.39, df = 2, p < 0.001).

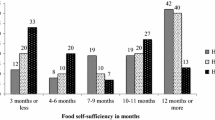

Most respondents reported small farms (median = approximately 4 ha, first quartile = 2 ha). Almost all respondents (92–95%) grew crops in the last year, and approximately 50% were women. Seventy-five percent grew rice and 76% grew vanilla, while few farmers grew crops like beans (1–20%) or vegetables (0–7%). We ranked the crops grown by the frequency of responses, and found that 50% of respondents grew only two of the top five crops, rice and vanilla (Fig. 3). Harvests of the two staple crops, rice and vanilla, did not differ significantly between households with a single-female head and other households (Wilcox test, rice harvest: W = 24,780, p = 0.13, vanilla harvest: W = 28,444, p = 0.28).

Up to 76% of respondents reported that they did not have enough food to feed the family during the previous three years. More than half (57%) reported that food insecurity was due to small arable land size, significantly more frequently than other causes of food insecurity (e.g., lost crops due to weather events, not enough money, or food in the market too expensive, chi-square = 786.48, df = 12, p < 0.001). In the analyses to follow, we tested which predictor variables had the strongest effects on the binary food insecurity dependent variable, especially focusing on the variables that relate to socioeconomics and agricultural practices.

The best fitting model explained 20% of the variance in food insecurity. The model included household size, land size, rice and vanilla harvests, and the interactions between household size and land size, and rice and vanilla harvests (Fig. 4). The probability of food insecurity increased with increasing household size (model averaged coefficient = 0.74, p = 0.002), and decreased with larger harvests of vanilla and rice, as well as land size (vanilla coefficient = −0.61, p < 0.01; rice coefficient = −0.48, p = 0.02; land coefficient = −0.50, p = 0.01, Fig. 4). There were also interaction effects (Fig. 5). Respondents that had higher yields of both vanilla and rice had significantly lower probability of food insecurity than farmers who had low yields on both, or high vanilla but low rice yields (Fig. 5a). Further, respondents that had small land size and large household size had a significantly higher probability of food insecurity than respondents with small land and small household size (Fig. 5b). The effect of household size on food insecurity decreased as land size increased such that when land size was large, there was no difference in food insecurity in relation to household size (Fig. 5b). For reference, 47% of respondents had land size smaller than the mean, 41% of respondents had household size larger than the mean, and 13% of respondents had both smaller land size and larger household size than the mean.

Effects of predictor variables on food insecurity in Madagascar. Food insecurity among farmers increased with the number of individuals in the household but decreases with the yield of vanilla and rice, and land size. The interaction effects between land size and household size, as well as rice and vanilla harvests, decrease food insecurity. There were no significant effects of other variables such as wealth indicators, education, single female households, and other variables not shown (Appendix Tables 4 and 5). Points represent the coefficient estimate and the standard error based on model averaging of the best candidate models (delta AIC <2, Appendix Table 5). Results based on logistic regression of data from 232 respondents

Interaction effects predicting the probability of food insecurity. Lines indicate the results of the logistic regression of the four variables and the interaction terms, with one of the independent variables discretized based on the mean value and ± 1 standard deviation. The shaded ribbons around lines indicate the 95% confidence interval around the estimated regression line. (A) The interaction between vanilla and rice yields indicates that the probability of food insecurity was lowest for respondents with both high yields of vanilla and rice, while those respondents with high vanilla yields but low rice yields had higher probability of food insecurity. (B) The interaction between land size and household size indicates that when land size is small, larger households have a higher probability of food insecurity than smaller households. When land size is large, there is no difference in the probability of food insecurity between large and small households

The number and diversity of livestock and crops, with multiple measures, were not significantly related to the probability of food insecurity (Appendix Tables 4 and 5). Food insecurity did not differ significantly between single female headed households and households with male heads or female heads with a partner (coefficient = 0.02, p = 0.95). Further, there was no effect of education, nor of household asset ownership (Appendix Tables 4 and 5). Food insecurity also did not differ across study villages.

4 Discussion

Food security is a major challenge for the agrarian communities we sampled in the SAVA region of Madagascar. Over 70% of respondents reported experiencing household food insecurity during a three-year time period. Farmers largely reported small land size as the cause of food insecurity, and our results showed quantitatively that farmers with larger farms had a lower probability of food insecurity. In addition, agricultural outputs, especially rice and vanilla harvests, decreased the probability of food insecurity. Increasing household size was related to increased food insecurity, unless coupled with larger land size. These results highlight the interactions between the socioeconomic and agricultural dimensions of food insecurity in this system.

Food insecurity is a tremendous global health challenge, and some of the patterns observed in this study are common across systems in low- and middle-income countries. The trend observed in Madagascar illustrates the high levels of food insecurity, which is affecting large areas of sub-Saharan Africa. For example, in Malawi, Benin, and Madagascar, more than 70% of respondents reported moderate to high food insecurity (Adjimoti & Kwadzo, 2018; Harvey et al., 2014; Mango et al., 2018). In contrast to patterns observed in other countries, we found a strong relationship between food insecurity, land size and household size. These variables were not significant predictors of food insecurity in Malawi or Benin, though small land size in general is still an important reason for food insecurity (Adjimoti & Kwadzo, 2018; Mango et al., 2018). Surprisingly, there was no difference in food insecurity related to the gender of the respondent or head of household, while in cross-cultural studies, women tend to experience food insecurity more often than men (Sinclair et al., 2019). In the studies of continental African populations mentioned above, higher education, off-farm income, and crop diversification significantly decreased food insecurity, while in our study, those variables were not significantly related to food insecurity. We discuss the possible mechanisms operating behind these factors below. These contrasting patterns illustrate that the drivers of food insecurity can be highly specific to different regions, and highlight the difficulty of applying generalized policy measures to meet the goal of ending hunger globally.

Variables found to be predictive of food insecurity in other low-income settings surprisingly did not have effects in this study, which will require further research to disentangle interacting factors. For example, single-female households did not report higher food insecurity than other households. This may be correlated to the finding that vanilla and rice harvests did not differ significantly between those groups. Further research should investigate the factors that could increase the resilience of single-female households and other such vulnerable groups in this population. For some variables, a lack of variation may explain the lack of effect on food insecurity. Opportunities to earn wage income are limited in this system, such that we cannot detect effects on food insecurity. We found that only 10% of farmer respondents had other forms of income, and thus there may not have been opportunities for income diversification in this study system. Similarly, for education, few respondents (<10%) achieved higher than primary school education, while almost all other respondents went to primary school. These observations make it difficult to detect patterns if they exist. These surprising findings offer new avenues for research to understand the factors affecting food security in northeast Madagascar.

The strong effect of land size on food insecurity has important implications for land tenure policy in Madagascar. The traditional system of land inheritance involves partitioning the parents’ land among their children (Laney & Turner, 2015; Omrane, 2018), and women tend to inherit less land than men (Widman, 2014). Thus, as future generations inherit smaller, fragmented parcels, farmers will need to produce more from less area, clear unclaimed forest, or rent / buy land, which is relatively expensive (Omrane, 2018). In addition, legally recognized landholdings are relatively rare because government policies to legalize land rights have had mixed success, making farmers’ rights to the land tenuous (Bellemare, 2013). Borrowing and loaning land is a common system for local economics, and is negotiated among community members (Laney, 2002; McConnel, 2009). Farmers can rent or borrow land from others, and then share the harvest they produce with the owner as payment, thereby reducing the amount of harvest available for the household. The land fragmentation problem is also a frequent theme affecting agricultural systems in other countries (Andersson Djurfeldt & Sircar, 2018), with effects on productivity and efficiency (Place, 2009). Though larger fields may produce larger harvests, productivity generally decreases with increasing land size due to the inefficiencies of input use on larger fields, especially when they are in fragmented parcels (Frelat et al., 2016). The downstream effects of land tenure systems on food security highlight the links between agriculture, health, governance, and well-being.

Further complicating the need for arable land is the need to conserve natural habitats. Many farmers have had to change their land-use strategies because of protected area management, as observed in this study system and in nearby sites in Madagascar (Llopis et al., 2019; Rakotonarivo et al., 2017). The villages in this study were situated adjacent to a national park, which affects their access to forested lands that might have otherwise been transformed for cultivation (Laney, 2002; McConnel, 2009). These cultural land tenure systems and resource management activities therefore affect the land size of future generations, which could impact their food security.

The strong positive association between food insecurity and the number of people in the household observed in this study has also been highlighted in food insecure communities across Africa (Akerele et al., 2013; Frelat et al., 2016; Misselhorn, 2005). In contrast, larger families for social support and labor in fields can increase food security. In this study, we showed that larger families (4+ members of the household) with small landholdings (<7 ha) had higher food insecurity than smaller families (<4 members) with small land, but as land size and productivity increased, there was less impact of family size on food insecurity. The interaction effects observed between household size and land size on decreasing food insecurity, as well as positive correlations between household size, land size, and harvests, demonstrate the importance of family size to these subsistence communities. Indeed, availability of family members for labor is an important component of social capital in both rice and cash crop agriculture (Laney & Turner, 2015). These associations are well known in the other rural settings, leading to debate over the directions of cause and effect (Clay & Johnson, 1992).

One intervention that could potentially improve food security in Madagascar, especially for households with small land holdings (almost 50% of the study sample), is increased access to women’s reproductive health care infrastructure and family planning (Starbird et al., 2016). Increasing access is an important step towards empowering women to make choices that are also important for their health (Gaffikin & Engelman, 2018; Robson et al., 2017). Family planning has been integrated into many population and environmental health programs to address issues of population growth and limited natural resources across geographic settings (Gaffikin & Engelman, 2018; Kock & Prost, 2017). In Madagascar, several international conservation and reproductive health NGOs, including Marie Stopes International, support family planning activities in rural communities (Robson et al., 2017). Such family planning interventions have had positive impacts in several sites (Gaffikin & Engelman, 2018), but they are not without their drawbacks and ethical concerns. Interventions must be framed within the local context and culture, and it is critical that participants are well informed and consenting (Baker-Médard & Sasser, 2020). Family planning can be one dimension of sustainable development that would alleviate food stress in this system, but only within the cultural and socioeconomic context.

Land and agricultural outputs are also important for socio-cultural reasons related to local economics (Laney & Turner, 2015). Rice is a fundamental staple to the Malagasy diet and culture, and is not only an important food source, but a source of income when portions of yields are sold in markets, as well as a way to pay for expenses and debts. In our study, increasing rice production was significantly related to decreased probability of food insecurity. To improve food security in this population, given declining land size, action is needed to sustainably intensify agricultural productivity. The common systems of rice agriculture in these areas, including both rainfed hillside rice involving shifting agriculture and lowland flooded paddy rice, are not sustaining households with enough food, in addition to degrading the natural and agricultural environment. Rice yields in many parts of Madagascar are declining due to eroding soil fertility (Styger et al., 2009). In shifting agriculture systems, the soil and natural vegetation need as long as 10 years in fallow to regenerate, compared to the 2–5 year fallow that is commonly practiced in Madagascar (Styger et al., 2007). Low input, low productivity swidden practice is deeply rooted in traditional systems of land tenure and claiming land (McConnell, 2002; McConnell et al., 2004), as well as an economically effective insurance policy that buffers farmers from market fluctuations in cash crop values (Laney & Turner, 2015).The importance of rice in this socio-cultural system and low yields are contributing to food insecurity.

There is a growing body of literature supporting the utility of conservation and regenerative agriculture techniques, including agroforestry, to improve productivity and sustainability (Lal, 2020; Rosenstock et al., 2019). These technologies have been piloted, and evidence exists for their efficacy in Madagascar (Messerli, 2000, 2006). Specifically, to increase soil fertility, farmers can use locally-made compost and manure, grow cover crops and keep soil covered as long as possible throughout the year, and strategically plant trees to amend soils, produce biomass, and reduce erosion. Conservation agriculture techniques including systematic crop rotations, mulching and minimum tillage as well as choosing appropriate varieties, and proper water management can all improve yields individually and in combination (Balasubramanian et al., 2007). Techniques such as the system of rice intensification (SRI) have shown two- to three-fold increases in rice yields by managing soils and water, optimizing plant root health, and increasing the bioavailable nutrients (Stoop et al., 2002). Adopting farmers have benefited from the increased yield and low starting inputs in terms of seeds and land size. Persistent barriers to widespread adoption of SRI include lack of access to irrigated valley-bottom land compared to hillsides, the increased labor intensity of SRI compared to traditional techniques, the complexity of the system, and a lack of extension services (Moser & Barrett, 2003). To improve the sustainability of land management in Madagascar, greater attention must be paid to the local context and rules governing land use, rather than only focusing on national policies repressing the use of forests and fire (Horning, 2005; Kull, 2002). Greater extension services are required to disseminate these new technologies to a broader audience, with consistent, long-term monitoring and consultation to realize their potential, as exemplified in other countries (Styger et al., 2011). Madagascar has a new, national initiative to increase sustainable agriculture extension services, supported by the World Bank, which could realize these goals (Jones et al., 2021). Sustained skills development to strengthen the capacity of rural farmers to adopt new techniques coupled with innovations to adapt techniques to local contexts can increase farmer resilience to food stress.

Growing few staple crops increases farmers’ vulnerability to low yields and catastrophic events like cyclones, pests, and droughts. Crop and livestock diversification can improve farmer resilience to such variability (Adjimoti & Kwadzo, 2018; Ijaz et al., 2019; Mango et al., 2018). In this system, crop diversity was relatively low across all respondents, and farmers were heavily reliant on a few staple foods, specifically rice, banana, and cassava. Further, domestic animal ownership was relatively rare, with most respondents owning less than five chickens, and only 10–45% owning cattle or pigs. By diversifying crops and livestock, farmers can spread their yield across the year, buffer themselves from extreme weather, and increase profitability (Rosa-Schleich et al., 2019). Diversified home vegetable gardens can substantially improve food security and nutritional outcomes, even in small spaces (Baliki et al., 2019; Galhena et al., 2013; Keatinge et al., 2011). These skills can be disseminated through workshops that teach about polyculture, crop rotation, and domestic animal husbandry. Such activities have been highly successful in other African settings (Leakey, 2018), and have begun in the SAVA region. Numerous fruit and vegetable crops are accessible and valuable in the SAVA region (Fig. 3), including fruit trees, vegetables and legumes, and tubers like cassava, and sweet potatoes.

Food crops are key to nutrient-dense diets, but cash crops can also alleviate food insecurity via revenue that can be used to purchase food. In this region, local markets with diverse food crops are available, with relatively good access to roads (Fig. 2). Vanilla agriculture is especially important in the SAVA region (Hänke et al., 2018), and 45–90% of farmers across the three villages in our sample reported growing vanilla. Given the economic value, this crop can create substantial revenue for impoverished, food insecure households. If farmers have cash debts to repay, they can often do so with portions of their vanilla harvest. The cash income can offset the inadequate food supply from smallholder subsistence activities (Laney & Turner, 2015), and the positive effect of vanilla yield on food security in our findings illustrates this point. Nevertheless, we found that farmers that produced less rice reported higher levels of food insecurity than those who produce more rice, even when vanilla production was high. This is most likely due to the subsistence system in the study area, in which most or all rice is for household consumption (Laney & Turner, 2015), and thus a low yield will directly translate to food insecurity. The volatility of vanilla prices and prevalence of theft (Hänke et al., 2018) may explain why farmers with high vanilla yields and low rice yields still report higher food insecurity than farmers who produce more rice. Therefore, vanilla agriculture may be one component of diversified agriculture to alleviate poverty and food insecurity in this system, within the framework of the interaction with rice harvests, described above. Other important cash crops include coffee (Laney & Turner, 2015), cocoa, cloves, pepper, cinnamon, and other spices (Fig. 3, Martin, Wurz, et al., 2020a, Martin, Osen, et al., 2020b).

A comprehensive program is needed to alleviate food insecurity, as well as improve human and environmental health in this setting. Holistic interventions that increase the productivity of home gardens with fruit, vegetable, and cash crops increase and diversify yields and food security for smallholder farmers, though they are not without their barriers (Baliki et al., 2019; Keatinge et al., 2011; Messerli, 2006). Increasing farm productivity is only one variable in a holistic framework. Income from off-farm labor and market access may have a greater impact on food security in parts of Africa than agricultural intensification (Frelat et al., 2016). A holistic paradigm would require international-, national-, and regional-level policies to increase equity and fair pricing of agricultural products along the value chains from international trade to the farmer to address the issues of price volatility that affect vanilla farmers, as described above. Further, improved land tenure policy is needed for farmers to have security in their land ownership. Agricultural extension services are needed to disseminate the values and skills of new and diversified cropping systems, coupled with skills development in agroforestry. These efforts will have positive impacts on people and the environment in this setting, leading to a more sustainable future.

Data availability

De-identified data are published on figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14619273.v1.

References

Adjimoti, G. O., & Kwadzo, G. T.-M. (2018). Crop diversification and household food security status: Evidence from rural Benin. Agriculture and Food Security, 7(1), 82.

Akerele, D., Momoh, S., Aromolaran, A. B., Oguntona, C. R. B., & Shittu, A. M. (2013). Food insecurity and coping strategies in south-West Nigeria. Food Security, 5(3), 407–414.

Andersson Djurfeldt, A., & Sircar, S. (2018). Gendered land rights and access to land in countries experiencing declining farm size. https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/16593/

Baker-Médard, M., & Sasser, J. (2020). Technological (Mis) conceptions: Examining birth control as conservation in coastal Madagascar. Geoforum, 108, 12–22.

Balasubramanian, V., Sie, M., Hijmans, R. J., & Otsuka, K. J. A. i. a. (2007). Increasing rice production in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities. Advances in Agronomy, 94, 55–133.

Baliki, G., Brück, T., Schreinemachers, P., & Uddin, M. N. (2019). Long-term behavioural impact of an integrated home garden intervention: Evidence from Bangladesh. Food Security, 11(6), 1217–1230.

Bartoń, K. (2013). MuMIn: multi-model inference. In CRAN

Bellemare, M. F. (2013). The productivity impacts of formal and informal land rights: Evidence from Madagascar. Land Economics, 89(2), 272–290.

Borgerson, C., Johnson, S. E., Louis, E. E., Holmes, S. M., Anjaranirina, E. J. G., Randriamady, H. J., & Golden, C. D. (2018). The use of natural resources to improve household income, health, and nutrition within the forests of Kianjavato, Madagascar. Madagascar Conservation & Development, 13(1), 45–52.

Borgerson, C., Razafindrapaoly, B., Rajaona, D., Rasolofoniaina, B. J. R., & Golden, C. D. (2019). Food insecurity and the unsustainable hunting of wildlife in a UNESCO world heritage site. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3, 99.

Brown, M. L. (2009). Madagascar's cyclone vulnerability and the global Vanilla economy. In E. C. Jones & A. D. Murphy (Eds.), The political economy of hazards disasters (Vol. 27, pp. 241–266). Altamira Press.

Clay, D. C., & Johnson, N. E. (1992). Size of farm or size of family: Which comes first? Population Studies, 46(3), 491–505.

FAO. (2020). FAOSTAT Madagascar. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#country/129

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO. (2020). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets.

Frelat, R., Lopez-Ridaura, S., Giller, K. E., Herrero, M., Douxchamps, S., Djurfeldt, A. A., Erenstein, O., Henderson, B., Kassie, M., Paul, B. K., Rigolot, C., Ritzema, R. S., Rodriguez, D., van Asten, P. J. A., & van Wijk, M. T. (2016). Drivers of household food availability in sub-Saharan Africa based on big data from small farms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(2), 458–463.

Gaffikin, L., & Engelman, R. (2018). Family planning as a contributor to environmental sustainability: Weighing the evidence. Current Opinion in Obstetrics Gynecology, 30(6), 425–431.

Galhena, D. H., Freed, R., & Maredia, K. M. (2013). Home gardens: A promising approach to enhance household food security and wellbeing. Agriculture & food security, 2(1), 1–13.

Golden, C. D., Fernald, L. C., Brashares, J. S., Rasolofoniaina, B. R., & Kremen, C. (2011). Benefits of wildlife consumption to child nutrition in a biodiversity hotspot. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(49), 19653–19656.

Golden, C. D., Rice, B. L., Randriamady, H. J., Vonona, A. M., Randrianasolo, J. F., Tafangy, A. N., Andrianantenaina, M. Y., Arisco, N. J., Emile, G. N., Lainandrasana, F., Mahonjolaza, R. F. F., Raelson, H. P., Rakotoarilalao, V. R., Rakotomalala, A. A. N. A., Rasamison, A. D., Mahery, R., Tantely, M. L., Girod, R., Annapragada, A., Wesolowski, A., Winter, A., Hartl, D. L., Hazen, J., & Metcalf, C. J. E. (2020). Study protocol: A cross-sectional examination of socio-demographic and ecological determinants of nutrition and disease across Madagascar [Clinical Study Protocol]. 8(500). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00500

Hänke, H., Barkmann, J., Blum, L., Franke, Y., Martin, D. A., Niens, J., Osen, K., Uruena, V., Witherspoon, S. A., & Wurz, A. (2018). Socio-economic, land use and value chain perspectives on vanilla farming in the SAVA Region (north-eastern Madagascar): The Diversity Turn Baseline Study (DTBS). U. report.

Hansen, M. C., Potapov, P. V., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S. A., Tyukavina, A., Thau, D., Stehman, S., Goetz, S. J., & Loveland, T. R. (2013). High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science, 342(6160), 850–853.

Harvey, C. A., Rakotobe, Z. L., Rao, N. S., Dave, R., Razafimahatratra, H., Rabarijohn, R. H., Rajaofara, H., & MacKinnon, J. L. (2014). Extreme vulnerability of smallholder farmers to agricultural risks and climate change in Madagascar. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1639), 20130089.

Hending, D., Andrianiaina, A., Maxfield, P., Rakotomalala, Z., & Cotton, S. (2019). Floral species richness, structural diversity and conservation value of vanilla agroecosystems in Madagascar. African Journal of Ecology, 58, 100–111.

Horning, N. R. (2005). The cost of ignoring rules: Forest conservation and rural livelihood outcomes in Madagascar. Forests, Trees Livelihoods, 15(2), 149–166.

ICF_International. (2012). Survey organization manual for Demographic and Health Surveys.

Ijaz, M., Nawaz, A., Ul-Allah, S., Rizwan, M. S., Ullah, A., Hussain, M., Sher, A., & Ahmad, S. (2019). Crop diversification and food security. In M. Hasanuzzaman (Ed.), Agronomic crops: Volume 1: Production technologies (pp. 607–621). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9151-5_26

Jones, J. P., Ratsimbazafy, J., Ratsifandrihamanana, A. N., Watson, J. E., Andrianandrasana, H. T., Cabeza, M., Cinner, J. E., Goodman, S. M., Hawkins, F., & Mittermeier, R. A. (2019). Last chance for Madagascar’s biodiversity. Nature Sustainability, 2(5), 350–352.

Jones, J.P.G., Rakotonarivo, S., and Razafimanahaka, J.H. (2021). Forst conservation in Madagascar: Past, present, future. EcoEvoRxiv, 31 March. 2021. Web.

Keatinge, J. D. H., Yang, R. Y., Hughes, J. D. A., Easdown, W. J., & Holmer, R. (2011). The importance of vegetables in ensuring both food and nutritional security in attainment of the millennium development goals. Food Security, 3(4), 491–501.

Kock, L., & Prost, A. (2017). Family planning and the Samburu: A qualitative study exploring the thoughts of men on a population health and environment programme in rural Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 14(5), 528.

Kull, C. A. (2002). Madagascar aflame: Landscape burning as peasant protest, resistance, or a resource management tool? Political Geography, 21(7), 927–953.

Lal, R. (2020). Regenerative agriculture for food and climate. Journal of Soil Water Conservation, 75(5), 123A–124A.

Laney, R. M. (2002). Disaggregating induced intensification for land-change analysis: A case study from Madagascar. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 92(4), 702–726.

Laney, R., & Turner, B. L. (2015). The persistence of self-provisioning among smallholder farmers in Northeast Madagascar. Human Ecology, 43(6), 811–826.

Leakey, R. R. (2018). Converting ‘trade-offs’ to ‘trade-ons’ for greatly enhanced food security in Africa: Multiple environmental, economic and social benefits from ‘socially modified crops’. Food Security, 10(3), 505–524.

Llopis, J. C., Harimalala, P. C., Bär, R., Heinimann, A., Rabemananjara, Z. H., & Zaehringer, J. G. (2019). Effects of protected area establishment and cash crop price dynamics on land use transitions 1990–2017 in North-Eastern Madagascar. Journal of Land Use Science, 14(1), 52–80.

Mango, N., Makate, C., Mapemba, L., & Sopo, M. (2018). The role of crop diversification in improving household food security in Central Malawi. Agriculture and Food Security, 7(1), 7.

Martin, D. A., Wurz, A., Osen, K., Grass, I., Hölscher, D., Rabemanantsoa, T., Tscharntke, T., & Kreft, H. (2020a). Shade-tree rehabilitation in vanilla agroforests is yield neutral and may translate into landscape-scale canopy cover gains. Ecosystems, 1–15.

Martin, D. A., Osen, K., Grass, I., Hölscher, D., Tscharntke, T., Wurz, A., & Kreft, H. (2020b). Land-use history determines ecosystem services and conservation value in tropical agroforestry. Conservation Letters, 13(5), e12740.

McConnel, W. (2009). Modeling human agency in land change in Madagascar: A review and prospectus. Madagascar Conservation Development, 4(1), 13–24.

McConnell, W. J. (2002). Misconstrued land use in Vohibazaha: Participatory planning in the periphery of Madagascar's Mantadia National Park. Land Use Policy, 19(3), 217–230.

McConnell, W. J., Sweeney, S. P., & Mulley, B. (2004). Physical and social access to land: Spatio-temporal patterns of agricultural expansion in Madagascar. Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment, 101(2–3), 171–184.

Messerli, P. (2000). Use of sensitivity analysis to evaluate key factors for improving slash-and-burn cultivation systems on the eastern escarpment of Madagascar. Mountain Research Development, 20(1), 32–41.

Messerli, P. (2006). Exploring innovative strategies for livelihoods in a slash-and-burn context in Madagasar: Experiencing the role of human geography in sustainability-oriented research. Geographica Helvetica, 61(4), 266–274.

Misselhorn, A. A. (2005). What drives food insecurity in southern Africa? A meta-analysis of household economy studies. Global Environmental Change, 15(1), 33–43.

Moser, C. M., & Barrett, C. B. (2003). The disappointing adoption dynamics of a yield-increasing, low external-input technology: the case of SRI in Madagascar. Agricultural Systems, 76(3), 1085–1100.

Neimark, B., Osterhoudt, S., Blum, L., & Healy, T. (2019). Mob justice and ‘The civilized commodity’. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 1-20.

Omrane, M. (2018). Sociodemographic pressure on land in Madagascar. In P. V. (Ed.), Population Studies and Development from Theory to Fieldwork (Vol. 7, pp. 109–132). Springer.

Place, F. (2009). Land tenure and agricultural productivity in Africa: A comparative analysis of the economics literature and recent policy strategies and reforms. World Development, 37(8), 1326–1336.

Powers, R. P., & Jetz, W. (2019). Global habitat loss and extinction risk of terrestrial vertebrates under future land-use-change scenarios. Nature Climate Change, 9(4), 323–329.

Rakotonarivo, O. S., Jacobsen, J. B., Larsen, H. O., Jones, J. P. G., Nielsen, M. R., Ramamonjisoa, B. S., Mandimbiniaina, R. H., & Hockley, N. (2017). Qualitative and quantitative evidence on the true local welfare costs of Forest conservation in Madagascar: Are discrete choice experiments a valid ex ante tool? World Development, 94, 478–491.

Robson, L., Holston, M., Savitzky, C., & Mohan, V. (2017). Integrating community-based family planning services with local marine conservation initiatives in Southwest Madagascar: Changes in contraceptive use and fertility. Studies in Family Planning, 48(1), 73–82.

Rosa-Schleich, J., Loos, J., Mußhoff, O., & Tscharntke, T. (2019). Ecological-economic trade-offs of diversified farming systems – A review. Ecological Economics, 160, 251–263.

Rosenstock, T. S., Dawson, I. K., Aynekulu, E., Chomba, S., Degrande, A., Fornace, K., Jamnadass, R., Kimaro, A., Kindt, R., & Lamanna, C. (2019). A planetary health perspective on agroforestry in sub-Saharan Africa. One Earth, 1(3), 330–344.

Schipanski, M. E., MacDonald, G. K., Rosenzweig, S., Chappell, M. J., Bennett, E. M., Kerr, R. B., Blesh, J., Crews, T., Drinkwater, L., & Lundgren, J. G. (2016). Realizing resilient food systems. BioScience, 66(7), 600–610.

Sinclair, K., Ahmadigheidari, D., Dallmann, D., Miller, M., & Melgar-Quiñonez, H. (2019). Rural women: Most likely to experience food insecurity and poor health in low- and middle-income countries. Global Food Security, 23, 104–115.

Starbird, E., Norton, M., & Marcus, R. (2016). Investing in family planning: Key to achieving the sustainable development goals. Global Health: Science and Practice, 4(2), 191–210.

Stoop, W. A., Uphoff, N., & Kassam, A. (2002). A review of agricultural research issues raised by the system of rice intensification (SRI) from Madagascar: Opportunities for improving farming systems for resource-poor farmers. Agricultural Systems, 71(3), 249–274.

Styger, E., Rakotondramasy, H. M., Pfeffer, M. J., Fernandes, E. C., & Bates, D. M. (2007). Influence of slash-and-burn farming practices on fallow succession and land degradation in the rainforest region of Madagascar. Agriculture, Ecosystems, Environment, 119(3–4), 257–269.

Styger, E., Fernandes, E. C., Rakotondramasy, H. M., & Rajaobelinirina, E. (2009). Degrading uplands in the rainforest region of Madagascar: Fallow biomass, nutrient stocks, and soil nutrient availability. Agroforestry Systems, 77(2), 107–122.

Styger, E., Aboubacrine, G., Attaher, M. A., & Uphoff, N. (2011). The system of rice intensification as a sustainable agricultural innovation: Introducing, adapting and scaling up a system of rice intensification practices in the Timbuktu region of Mali. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 9(1), 67–75.

UNDP. (2020). Goal 2: Zero Hunger. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/

Ward, P. S., Bell, A. R., Droppelmann, K., & Benton, T. G. (2018). Early adoption of conservation agriculture practices: Understanding partial compliance in programs with multiple adoption decisions. Land Use Policy, 70, 27–37.

Widman, M. (2014). Land tenure insecurity and formalizing land rights in Madagascar: A gender perspective on the certification program. Feminist Economics, 20(1), 130–154.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Malagasy Institute pour la Conservation des Ecosystems Tropicaux and the Duke Lemur Center SAVA Conservation for logistical support, and the Direction Regional du Sante Publique for permission to conduct the research. We greatly appreciate the communities in which this study was conducted for welcoming us into their villages, their homes, participating in our studies, and teaching us about Malagasy culture. In particular we thank the following individuals who made this work possible: Desiré Razafimatratra, Tonkasina Jacques Harrison, Edouard Mazandry, Desire Rabary, Ramisely Ndrianjafy, Dimbisoa Armand, Tiomily Velomarina, Herlin Edmond, Seraphin Intemany, Francine Rasoanesy. We thank Thio Rosin Fulgence for helpful feedback that improved the quality of the manuscript, R. Fitzgerald and L. Regula for assistance in field work, C. Novack for help in data processing, and two anonymous reviewers whose valuable feedback improved the quality of the manuscript. This is Duke Lemur Center publication # 1481.

Code availability

Code for running analyses are provided for the R statistical environment on figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14619282.v1.

Funding

Duke University Bass Connections grant, the Duke University Provost Collaboratory program, and the NIH-NSF-NIFA Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Disease award (5R01-TW011493-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

James Herrera, Randall Kramer, Michelle Pender, and Charles Nunn designed the study, Rabezara Jean Yves, Ny Anjara Fifi Ravelomanantsoa, Miranda Metz, Courtni France, and Ajile Owens collected data, James Herrera analyzed the data and wrote the first draft, all authors contributed to the final draft and approve submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and data security statement

Before conducting research, we secured all permit documents related to ethical review of the methodology (Duke University IRB 2017–1366, in-country permits 245-ICTE/18 and 313-ICTE/19). Data were entered directly in a Samsung tablet using Qualtrics, and then downloaded onto a secure server at Duke University. Names were replaced with a unique identity number. All survey instruments were adapted to the local context so that they were culturally mindful and sensitive to the mental and physical well-being of the participants. Research assistants, drawn from the population in SAVA and neighboring regions, were trained in the administration of the survey instruments and in ethical data collection and security. The research assistants all signed contracts of confidentiality in which they attested to rigorous standards of data security.

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 179 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herrera, J.P., Rabezara, J.Y., Ravelomanantsoa, N.A.F. et al. Food insecurity related to agricultural practices and household characteristics in rural communities of northeast Madagascar. Food Sec. 13, 1393–1405 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01179-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01179-3