Abstract

Nutrition-sensitive agriculture is a concept that aims to narrow the gap between available and accessible food and the food needed for a healthy and balanced diet for all people. It explicitly incorporates nutrition objectives into agriculture and addresses the utilization dimension of food and nutrition security, including health, education, economic, environmental and social aspects. Based on this concept, the present paper presents a synthesis of a recent desk study which took stock of innovative approaches to improve the positive nutrition-related impacts of agriculture and related food systems and provides recommendations for future programmes. By providing an overview on specific cross-cutting themes relevant to nutrition-sensitive agriculture and presenting examples from various countries on how nutrition objectives can be incorporated into the agro-food systems, the paper identifies commonalities and parameters that are entry points into a system within which local nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches will have a realistic chance of success. The variables in the system are interlinked and contribute to a balanced nutrition of the population. By changing or fine-tuning one or more of the entry points, the whole system can be improved. The paper also highlights the current fragmentation in approaches towards more nutrition-sensitivity in agriculture and concludes that, where collaborative approaches are undertaken, there is a greater likelihood that shared projects will be implemented and/or be successful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Predictions of a world population of 9 billion by the year 2050, changing lifestyles and affluence leading to the consumption of more animal products, land degradation and the expected increase in severe weather events which have an immediate effect on food production, and rising mineral oil prices which make the production of biofuels on food crop land ever more attractive, call for new concepts of agricultural food production. At the same time, almost 870 million chronically undernourished people, more than 2 billion people suffering from nutrient deficiencies and more than one billion overweight or obese people are a sign that strategies to improve nutrition have failed and urgently need to be revised (FAO 2012a). National and international efforts towards improved food and nutrition security are further influenced by pandemics, such as HIV/AIDS, which may have knock-on effects on agricultural production, socio-economic trends, such as urbanization, and the globalization of food systems.

The current global agro-food systems, which are predominantly based on grain production, will not be able to satisfy the increased demand for food quantity and quality in the decades to come unless more flexible, locally adapted systems are in place that provide food and nutrition security despite increased climate variability, social insecurity, land ownership shifts and resource degradation. The 2008 food price crisis was a wake-up call to the world community and the interpretation of its causes (e.g. Headey and Fan 2010) and has led to important insights into the fragility of the agriculture and food economy in many developing countries and the related fragility of social systems. Possible responses are integrated approaches which link agriculture, health and nutrition, education and other sectors focussing on more diversified, local production systems, and taking a more holistic view of the factors which contribute to both agricultural and food systems, i.e. the agro-food system as a whole. These include consideration of a more diverse range of food sources, processing methods and marketing channels, which could lead to more balanced and nutritious diets. The role of marketing needs to be investigated because of its dual role of providing cash to the producers who can use it to purchase nutritionally more valuable food and of providing consumers with fresh or processed food that can contribute to a balanced diet, provided they have access to it, can afford it and have the knowledge of how to use it. More bio-diverse agricultural systems, which include underutilized or minor grains, pulses, fruits, vegetables, root and tuber crops – in addition to the common staple crops – are thought to provide the means for a balanced diet and environmental resilience. Many of these alternative food crops not only diversify agro-ecosystems, they may also be adapted to extreme climatic conditions, provide resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses and produce harvestable yields where major crops may fail (e.g., Keatinge et al. 2010, Kahane et al. 2013). More diverse and integrated farming systems, such as agroforestry, agro-pastoral systems or integrated floodplain management offer interesting nutrition-sensitive alternatives because they provide a buffer against the effects of climate change. Finally, diversity of production might also provide protection from internal and external market disruptions and hence also buffer and stabilize the diets of consumers.

Nutrition-sensitive agriculture is a concept that expands the scope of the agro-food system to a system encompassing all elements from input delivery, production of food to distribution networks, storage, processing, retail and utilization including consumption with a special view to nutrition. Thus the scope expands from merely producing a sufficient amount of calories to taking into account vitamins, minerals and other micro-nutrients that are required for healthy living, environmentally sustainable food production, and food processing and utilization to ensure that the food reaches the consumers in an optimal state. But nutrition-sensitive agriculture goes beyond the production and provision of healthy food along the food chain. Because there are often specific vulnerable groups of people within local, national and regional communities who suffer most from insufficient availability of and access to nutritious food (e.g. tribal groups, women, children, sick or elderly people), nutrition-sensitive agriculture adopts approaches that recognize the specific vulnerability of these groups. These include recognition of basic human rights such as the “Human Right to Adequate Food” for all people (UNHCHR 2010), which has been written into many constitutions.

Nutrition-sensitive agriculture thus takes a systems approach, linking sectors and intervention levels while aiming to deliver nutrient-rich, diversified and balanced diets to all consumers throughout the year. By doing so, nutrition-sensitive agriculture puts a specific “nutrition lens” on agriculture with the aim of sensitizing the agricultural sector to the importance of nutrition and health aspects within food security and to better connect agriculture, health and nutrition sectors within the agro-food system. Thus, it incorporates fully the concept of food and nutrition security as currently accepted (CFS 2012), which includes the stable availability of and access to food as well as its utilization, including quality aspects. The concept also requires closer links between the agriculture, nutrition, health, environment and education sectors insofar as agriculture aims to provide healthy and nutritious food in a sustainable, environmentally-friendly manner. Consumers not only need to have access to this food, they also need to know how to use it for healthy living – as ultimately, healthy children learn better and healthy people perform more successfully in life. The challenge is that the boundaries of the term “nutrition-sensitive agriculture”, and thus responsibilities for action, are not clearly defined and the sectors often work in isolation from one another, thus compromising the potential for joined-up action.

A number of initiatives seek to foster cross-sectoral collaboration. These include high-level initiatives such as the Millennium Development Goals and the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the “2020 Vision for Food, Agriculture, and the Environment” initiative of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), which aims to develop a shared vision and consensus for action to meet future world food needs while at the same time reducing poverty and protecting the environment (Fan and Pandya-Lorch 2012), and the new collaborative research programme “Agriculture for Improved Nutrition and Health” of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) (IFPRI 2011). The United Nation’s “Scaling Up Nutrition” (SUN) initiative is a broad collaborative effort to address malnutrition, especially of children, by the World Bank, UNICEF, the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Food Programme (WFP) and a wide range of developing country partners, civil society organizations, and bilateral agencies (SUN 2010). The private sector is also active, for example with the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). The growing interest in nutrition-sensitive agriculture and food-based approaches is reflected in several in-depth reviews on the topic (e.g. Thompson and Amoroso 2011; FAO 2012b).

With this paper, the authors aim to synthesize experiences and insights of international experts in a consultative process and present general recommendations based on this process that help development professionals to design site and situation-specific nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions.

Approach

This paper presents a synthesis of an unpublished desk study conducted by the Food Security Center of the University of Hohenheim (Virchow 2013). For the study, desk reviews were commissioned from international experts to address specific cross-cutting themes (gender, plant breeding, production and processing, home and community gardens, urban agriculture, market integration) and to review case study examples from eight countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Cambodia, Egypt, Malawi, Mongolia, Philippines and South Africa).

This synthesis paper will provide example cases from the desk reviews, identify commonalities and entry points and formulate pragmatic recommendations to help development experts in the design of successful nutrition-sensitive agriculture initiatives in different locations. Recognizing that any approach will by necessity be location-specific, parameters were identified that are “must-have” cornerstones, within which local approaches will have a realistic prospect of success. One of the factors limiting our analysis and that of the country and thematic reviews, however, was a distinct lack of objective evidence on the impacts of various interventions on the health and nutrition status of people, caused partly by the design of the reviewed cases, a lack of statistically meaningful data, project designs that did not focus on nutrition in the first place, or a lack of strong monitoring and evaluation processes.

Entry points for fostering nutrition-sensitive agriculture

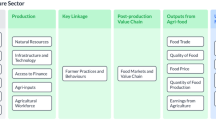

The crucial elements that were found to be relevant entry points to kick-start or improve nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches are depicted in Fig. 1 and include: (i) enabling policies and government structures expressing the political will to fight malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies, (ii) appropriate mechanisms for intersectoral and inter-organizational collaboration within the countries, (iii) increased awareness of nutrition-sensitive agriculture and capacity to design and implement relevant projects at different levels, (iv) appropriate focus on those groups who will benefit most from nutrition-sensitive approaches without being exclusive, and (v) an approach cognizant of the elements of the food chain and recognizing the links between its various elements from production through to consumption as well as relevant technological, economic and societal innovations.

They signify components within the agriculture-nutrition continuum through which positive changes can be triggered, keeping in mind that a nutrition-sensitive food system as a whole is interrelated and works best when all components are in place. Besides these elements, a range of external drivers, such as climate change, urbanization, pandemics etc., play important roles in supporting or threatening nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches although they cannot normally be directly influenced by the components of the system.

Enabling Policies

The political climate within a country is paramount to the focus and the success of development projects. Where policies exist that support nutrition-sensitive approaches and where active government processes stimulate joint agriculture-nutrition approaches, there is a relatively high likelihood of success in implementing such programmes and projects with the theoretical implication of improved, nutrient-rich and balanced diets, and eventually, improved health status of consumers. However, the sustainability of such initiatives relies heavily on sustained political will.

The case of Brazil (Maluf et al. 2013) illustrates the potential of policy changes. The reforms introduced by the Lula Government were targeted at strengthening the family farming sector and creating and securing formal jobs and are credited with improving the nutritional status of large parts of the society. National legislation towards the establishment of a National System for Food and Nutrition Security explicitly mentioned the right of access to good quality food and strives towards sustainable strategies of food production, distribution and consumption. Central to this goal were strengthening small-holder family farms and the respect for the diversity of cultures and livelihoods. The “Zero Hunger Program”, launched in 2003, was a starting point in internalizing integrated nutrition-sensitive approaches which were formalized with the National Law for Food and Nutrition Security. The Brazilian case also demonstrates the value of developing national nutrition-sensitive legislation not in a vacuum but in interaction with civil society, whose members promote and advocate new approaches in dialogue with the government, although this may be a slow and thorny process.

Other examples include the effect of the ratification of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Cambodia, which triggered the setting up of nutrition-focused institutions within the agricultural sector (Darith and Sopheap 2013). In the Philippines, the country’s food security programme was boosted with an Executive Order by the President in 2009 (Executive Order 776) encouraging the production of high-quality food by charging all governors and mayors to set aside funding for the programme and to designate project supervisors in their respective areas (Zamora et al. 2013). Such high-level political influence is not always the case but certainly has an important impact on the implementation (though not necessarily on the success) of nutrition-sensitive agriculture projects. South Africa has recently developed its National Development Plan which calls for a range of interventions across the entire agro-food systems, including linkages with the education and health sectors, to reduce hunger and malnutrition. A Food Security Policy premised on the Bill of Rights in the Constitution is currently being developed (McLachlan and Landman 2013).

In contrast, in Mongolia, where policies and development programmes are centrally planned and executed, a move towards more quality-oriented production systems was more difficult to realize, as illustrated by the case of the Third Virgin Land Campaign, which operates at a comparatively large scale and focusses on increasing the yield of export crops (Baast 2013).

Mechanisms for collaboration

Cases reported in the country reviews which were considered as relatively successful in terms of incorporating elements of nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches, always involved partners from different sectors, such as public and private sectors, government and non-governmental agencies and/or line ministries within government (e.g. health, agriculture, education). In several countries, the increasing awareness of a need to connect the entire agro-food system have led to the development of agencies that foster closer interaction at sectoral level among agriculture, nutrition and health. However, in many countries these sectors are still disjointed. A critically important role in the implementation of nutrition-focused initiatives is played by community-based organizations and by NGOs, in particular in the health sector (e.g. through community health programmes, health education, home food processing) but also in agricultural production (e.g. home gardens, small animal rearing) and post-harvest handling education programmes. There is evidence that where government actively supports or initiates a programme, which is then implemented jointly by government and civil society/NGO partners, these initiatives have higher prospects of sustainable success than those supported by single concerns .

A few examples from different countries show the range of collaborative arrangements in place. In Cambodia (Darith and Sopheap 2013), the government has actively supported the establishment of a number of bodies to ensure effective implementation of joint food security and nutrition approaches, including CARD (Council for Agricultural and Rural Development), the National Food Security Forum, the Technical Working Group on Food Security and Nutrition (a joint mechanism for food security and nutrition coordination), and the Food Security and Nutrition Information System which was established within CARD to serve as a national entry portal to all relevant information on food security and nutrition in Cambodia. A good example of a highly intersectoral collaborative project in Cambodia is the MDG-Fund Joint Programme for Children, Nutrition and Food Security (Jeddere-Fisher and Khin Meng Kheang 2011).

In the Philippines (Zamora et al. 2013), a National Food and Agriculture Council (NFAC) was created as early as 1969 and a separate National Nutrition Council (NNC) in 1974. In 1988, the NNC was reorganized and its administrative responsibility was transferred to the Department of Agriculture, underlining the important link between agriculture and nutrition.

Similarly, Brazil (Maluf et al. 2013) has set up an Interministerial Chamber for Food and Nutrition Security (CAISAN) as the governmental body with the responsibility for coordinating food and nutrition security-related actions among 19 State Ministries. The National Council for Food and Nutrition Security (CONSEA) is an intersectoral space where 38 civil society representatives coming from different social sectors, professions and regions meet with officials from these 19 Ministries to discuss, design and evaluate programmes and actions that focus on the many dimensions of food and nutrition security. This framework operates by cascading down from Federal (national), through State to municipal levels. Despite a certain degree of coordination that has taken place, integrating nutrition into agricultural and rural development policies is an ongoing challenge in the agendas of CONSEA and CAISAN. The possibilities and difficulties for establishing joint actions that connect agriculture, health, nutrition and social sectors, with a view to forging closer links between food production and healthy eating, are illustrated by these two bodies (Burlandy et al. 2010).

In Mongolia (Baast 2013), the National Programme on Food Security emphasizes collaboration between government sectors, including the Ministry of Industry and Agriculture, the State Professional Inspection Agency, the Ministry of Health, the Agency for Standardization and Metrology, the Ministry of Population Development and Social Protection, the Ministry of Environment and Green Development, the Ministry of Education and Science and the National Emergency Management Agency. By defining substantial involvement of the Ministry of Industry and Agriculture in addressing nutritional aspects, the programme also contributes to a paradigm shift within the food and agriculture sectors in favour of nutrition-sensitive agriculture in contrast to the common ambition of maximizing production regardless of the significance of such trends for nutrition.

The case of Malawi (Msiska 2013) on the other hand illustrates that splitting agriculture and nutrition may prove beneficial if it allows specific attention to be given to nutrition-sensitive approaches. The Food and Nutrition Security Policy was initially developed as a joint agriculture/nutrition framework but the Cabinet decided to split it into two separate frameworks, to give adequate attention to each of the two issues and especially to raise the profile of nutrition security. The split was also recognition of the fact that agricultural growth does not automatically translate into the desired national nutrition outcomes. Following the split, the Department of Nutrition, HIV and AIDS within the Office of the President and Cabinet was tasked to develop a comprehensive National Nutrition Policy and Strategic Plan (NNPSP). At the same time, specific nutrition objectives, committing the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security and its stakeholders to promote a number of nutrition-related interventions, were also incorporated into the country’s Agriculture Sector Wide Approach (ASWAp) which was developed under the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security. Thus nutrition objectives were incorporated in both strategic documents.

The private sector plays an important role as partner in the entire food chain, from seed supply to processing, food fortification and sale. Although formal mechanisms to engage with the private sector were rarely identified by the reviews, several examples indicated that public-private partnerships were implemented, for example in Brazil (Curralero and Santana 2007, cit. in Maluf et al. 2013) and South Africa (Lahiff et al. 2012, cit. in McLachlan and Landman 2013).

Awareness creation/capacity building

Awareness creation about the role of agriculture in household nutrition takes place at different levels. It includes the sensitization of decision-makers about a link between nutrition and agriculture that goes beyond food security, as well as increasing the capacity of groups of vulnerable people to produce, handle and prepare food that has higher nutritional value and to consume nutritious and balanced diets. Specific awareness-raising projects have been initiated in most of the surveyed countries to some extent. The above-mentioned interlinkage and interdependency of the different entry points is especially obvious for awareness creation: positive impacts on the nutrition behaviour of consumers and their health status can only be realised when the consumers are enabled and entitled to sufficient high-quality food.

Capacity building and education programmes, specifically for women and young mothers, have already been implemented on a large scale for “pure” nutrition projects – with a specific focus on the nutrition of infants and young children. For example, one of the elements of the above-mentioned Cambodian MDG-Fund Joint Programme is the development and implementation of a nationwide comprehensive Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) plan comprising mass media, interpersonal communication and social mobilization for breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation for women during pregnancy and after birth. Next steps towards nutrition-sensitive agriculture are the inclusion into training programmes of elements of agricultural production, processing and utilization and the setting up of demonstration sites, for example through school gardens. There are many programmes in the countries targeting women as the key household food providers and children as the next generation of nutrition-sensitive citizens. Schools in particular play a very important role in capacity building on nutrition aspects as well as in providing nutritious food to the young and vulnerable through school meals or school garden projects. Most of the country reviews reported on training and awareness raising programmes for women in food processing and home gardening, some initiated through government programmes and some through NGOs.

In the Philippines, there are examples of the promotion of nutritious crops by using folk songs, theatre and simple slogans that seem to have widespread success, such as “FAITH gardening” (= food always in the home), “BIG” (Bio-intensive gardens; a school garden project) and coining of the term “MACK-P plant” for a set of nutritious vegetables. The “Adopt-a-Station” programme was launched in Region XII to encourage all radio and TV stations in the region to establish vegetable gardens and to promote the importance of backyard gardening to the general public (Zamora et al. 2013).

Another approach was taken in South Africa, where the Food Price Monitoring committee plays an important role in monitoring food prices of a balanced basket of regularly consumed foods. This initiative has been operating since 2005 and has built up a valuable database on market dynamics. It has also generated increased attention to food price trends in rural and urban areas of the country (McLachlan and Landman 2013).

Stakeholders

Most of the projects considered in the reviews are directly focused on nutrition-vulnerable or disadvantaged groups, including women, children, sick and elderly, tribal groups, poor urban (slum) dwellers and others. Although a specific focus on these vulnerable groups is justified to ensure their direct support and empowerment, it is also important to involve and engage the entire community (family, village etc.) to achieve sustainable change and impact.

Women

Because household nutrition is still mostly the domain of women in rural communities it is appropriate to take stock of how well women are integrated in decision-making capacities and whether their specific nutrition needs and responsibilities are recognized and addressed. By taking a ‘human rights based approach’, i.e. viewing food security, poverty and nutrition as a human rights issue, Beuchelt (2013) demonstrated that a gender perspective is necessary to make nutrition-sensitive agriculture work. A look at the possible trade-offs of innovations shows that many promising interventions may actually weaken the rights of women, for example by promoting higher yielding improved maize varieties, which benefited men but disadvantaged women because the cooking time of the new varieties was longer and thus required more firewood, implying more labour input by the women.

Often overlooked is the fact that, although there are a host of projects focusing on women, the extension service in many countries is male-dominated. In hierarchical and gender-segregated societies, training tends to be targeted at the men, in the – often naïve – assumption that the knowledge is then diffused to the female household members. In fact, it is very difficult for the extension officers to directly reach women and interact with them in a meaningful way. Participatory extension approaches have been successfully used to break through this barrier. As described by Msiska (2013), female extension officers are employed in Malawi with the specific task to promote nutrition education amongst women and female farmers on nutrition and health issues. In addition, efforts have also been made to involve male farmers in nutrition extension programmes through the male extension staff.

An important element in gendered approaches is also the provision of opportunities for women to earn income, as this will often be transformed into better household nutrition via the purchase of higher-quality food. Although the evidence is often weak, a direct positive link has been shown between higher earnings by female household members and child nutrition, whereas this was not the case for male income earners (World Bank 2009; Birkenberg 2013). Similarly, a link could be established between women’s control over land and physical assets and increased agricultural productivity, and improved child health and nutrition (Quisumbing 2003).

In Bangladesh (Rahman and Islam 2013), the NGOs Proshika and BRAC, working in separate projects with the Department for Livestock Services (DLS), made a special provision for rural women to generate employment and income through different development, employment and income generating programmes, for which micro-loans were made available. Poultry production on a small scale as in the Smallholder Livestock Development Project (SLDP), the Poultry for Nutrition Project (PNP) and the Participatory Livestock Development Project (PLDP) was useful in improving local backyard poultry under scavenging and semi-intensive systems, where women traditionally play the more important role. Through the project interventions, women were able to operate and manage technical enterprises such as broiler, layer and duck farms efficiently with a high return on investment.

The review from Egypt (Yordy and Laamrani 2013) suggested that the nutrition situation of women in particular might be improved in traditional households by taking advantage of the roles of women in the family, which is focused on the house and home garden. The women’s traditional role gives them few opportunities to consume nutrient-dense foods such as meat (which is primarily served to male members of the family). But interventions focussing on the women’s sphere of responsibility – household gardens and tending to small animals and poultry – can provide opportunities to foster increased dietary diversity and the consumption of more nutritious food. Even if differences in the quantity and quality of food that women consume vis-à-vis men continue, it is possible to ensure a base level of nutrition when women have a role in its production for the household and do not rely entirely on the cash brought home by men. Expanding the sphere of activities that women undertake may thus indirectly help to insure that the entire household has access to a more diverse diet.

Children

Recognition of the importance of sufficient vitamin and mineral nutrition in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life from conception to 2 years of age has led to a number of specific food supplementation projects for this age group. Older children are often included in projects that focus on nutrition education, for example by developing school gardens that also contribute to healthier school meals. South Africa and the Philippines reported on several projects in that respect. However, many of these projects have only started recently so that a possible link to a better nutritional status of children has not yet been established. A Brazilian review (Maluf et al. 2013) showed how increased awareness of nutritional principles, together with government incentives, has led to change. The National School Meal Programme (PNAE) had originally been launched in 1954 but was changed significantly in 2003. It is an impressive example of an integrated approach that supports farmers, local entrepreneurs and the children.

Urban consumers

In countries and regions with a growing urban population there is also an increasing focus on urban consumers. Inhabitants of informal settlements are amongst the most vulnerable in terms of undernutrition, while a city lifestyle increasingly leads to an unbalanced diet and malnutrition. The “nutrition transition” – away from a diverse diet based on fresh agricultural products towards a diet including heavily processed foods, low in fibre and rich in trans fats, sugars and salt – is now also being observed in many developing countries. It is more prevalent in urban than in rural areas. Increased cases of obesity (Popkin 2001), cardiovascular diseases (Reddy and Katan 2004) and diabetes have been linked to the nutrition transition (Dans et al. 2011, McLachlan and Landman 2013) together with severe economic consequences (Sage 2012). In Egypt, government subsidies especially on wheat and sugar may have inadvertently played an important role in this development (Yordy and Laamrani 2013).

Specific examples addressing the nutrition transition and urban consumers are documented from several countries. The South African review (McLachlan and Landman 2013) highlighted several initiatives through which healthy, organically grown food, often produced in local communities, was distributed or sold to urban consumers. For example, the association Abalimi Besekhaya works with poor informal settlements around Cape Town on sustainable food production and sells the produce on a weekly basis to markets in Cape Town City. However, links to better nutrition have not yet been measured.

The Philippines review (Zamora et al. 2013) also showcased several projects for urban consumers, amongst them the aforementioned Executive Order 776 (Rolling Out the Backyard Food Production Programmes in the Urban Areas), which was issued by the President to boost the government’s food security programme and at the same time generate employment for the poor by strongly promoting backyard food production in urban areas. The EO was issued to strengthen backyard food production as part of the Comprehensive Livelihood and Emergency Employment Programme (CLEEP). Information about nutrition indicators is not available.

In Brazil, the Inter-Sectoral Plan for Prevention and Control of Obesity promotes lifestyles (such as more physical exercises) and proper and healthy nutrition. The programme aims to facilitate access of the population to healthy and appropriate food (such as cereal and legume staples, fruits and vegetables, fish or minimally processed foods) and to strengthen local food production, provisioning and consumption, thus reinforcing the interaction between agriculture and nutrition (Maluf et al. 2013).

Food chain

Whilst the focus of nutrition-sensitive agriculture at one end of the food chain is the production of nutritious food, at the other end it focusses on local, regional or global marketing and finally, on the consumption of safe and nutritious produce. So far, efforts have been made to enhance the livelihoods of food producers and other actors in the agro-food systems from production through to marketing and consumption, but these efforts have rarely been nutrition-sensitive nor have they incorporated the explicit purpose of achieving nutritional goals (Hawkes and Ruel 2012). Furthermore, value-chain approaches to agricultural development currently tend to perceive the chain primarily as being responsive to consumer demand, rather than recognizing the influence the chain can also have on consumption patterns. However, there is a mutual influence: consumption patterns can influence what is being produced; at the same time, production and post-production activities up to the supply of specific nutritious food items in the market (from neighbourhood stores to supermarkets) can influence what is being consumed. Recognizing that so far the importance of nutritious food has not been valued, this section will examine examples throughout the food chain in which elements of the chain can have positive impacts on the nutritional value of food.

Production

Nutrition-sensitive initiatives and projects in agriculture often focus on research and the promotion of improved agronomic practices or inputs, such as efforts to develop and/or promote crops that have high content of relevant vitamins or minerals. One example is orange-fleshed sweet potato which has higher provitamin A/beta carotene content compared to the traditional white-fleshed varieties that are commonly grown in some African countries. Other examples include iron-rich cereals and beans. Higher nutrient contents in crops can also be achieved through agronomic practices, for example by modifying the soil pH in order to make micronutrients more available to plants. These approaches are complemented by calls for sustainable, often organic, production as a first step towards nutrition-sensitive agriculture as this reduces the danger of pesticide residues and contamination of food, soils and water with other chemicals (e.g., Keding et al. 2013).

In addition, increased agrobiodiversity plays a very important role in nutrition-sensitive production approaches. For example, a clear link between vegetable diversity on the farm and diversity in the diet has been established (e.g., Figueroa et al. 2009; Masset et al. 2012). Harvest calendars help to assess periods of high supply of specific crops, which can be matched against demand. Specific “nutritional calendars” can map nutrition requirements (Keding et al. 2013). For example, a project run by the NGO LI-BIRD in Nepal carried out an inventory of existing plant species and developed nutritional calendars, which showed which nutrients were available throughout the year from the plants in the home gardens. Following discussion with farmers, the project then developed “diversity kits”, i.e., seed packs with species that could supplement and balance the nutrients that were already available from the gardens (Gautam et al. 2009).

Although not yet fully integrated into the nutrition-sensitive agriculture debate, livestock keeping, including poultry and dairy cattle, and aquaculture also have great potential to combat micronutrient and vitamin malnutrition. Meat, eggs and fish are rich sources of animal proteins, essential fatty acids, vitamins and minerals. It has been documented that the rearing of small animals, keeping of dairy cattle and pond aquaculture can increase household consumption of protein, vitamins and minerals (e.g., Roos et al. 2007; Rahman and Islam 2013).

Breeding and seed systems

Plant and animal breeding play an important role in nutrition-sensitive agriculture. Christinck (2013) described how the more successful nutrition-sensitive approaches to plant breeding have become more holistic and include producers, consumers and other stakeholders from the early conceptualization of breeding programmes. Plant breeding efforts to improve nutrition can address several entry points, for example improving yield and yield stability under marginal production conditions, adding value to varieties to improve their marketability and thus provide income opportunities for producers, improving the nutritional value of food crops by purposively including nutritional aspects into selection schemes (“biofortification”), or reducing any negative effects on human health and nutrition by removing anti-nutritional or harmful substances and reducing negative effects on the environment (and thus also on human health) by selecting cultivars that require less pesticide or fertilizer inputs.

A renewed consideration of underutilized or neglected crops can also be of importance for nutrition-sensitive agriculture. Many local crops or varieties compare favourably with “modern” ones in terms of yield and quality, especially under marginal conditions. In addition, they may be used as medicines or traditional health boosters. Often, there is specific knowledge linked to the production, processing and use of these crops that is in danger of being lost together with the varieties (Jaenicke and Azam-Ali 2009).

In addition to, or possibly even more important than, developing new improved crop varieties, is a functioning seed system that allows for unimpeded access to quality seed (or other forms of planting material) for vulnerable groups. Thus, seed production and diffusion to specific user groups should be considered from the outset of a breeding programme, and are of great importance for priority setting, i.e. in view of variety types to be developed. These links could thus be of growing importance for a nutrition-sensitive plant breeding approach.

Increasing micronutrient content has been successful in various crops. Notable examples include “New Rice for Africa” (NERICA) and orange-fleshed sweet potato (OFSP) derived from classical breeding and/or biotechnology, and “Golden Rice”, a transgenic (GM) crop. However, it has been recognized that crop introductions in isolation will not lead to sustainable and positive effects on the nutritional status of vulnerable groups. Instead, the entire food chain needs to be addressed, including processing, marketing and education programmes (Low et al. 2009). Although recent information is available about the positive effect of introducing biofortified crops on health status, mainly from HarvestPlus (Hotz et al. 2012), most projects to date have been limited pilot projects and comprehensive impact assessments are still outstanding.

Home and community gardens and urban agriculture

The concept behind home and community gardens, in which fruits, vegetables and other crops are grown in confined spaces, often together with poultry and small animals, is to bring nutrient-dense and nutritious food closer to consumers. Gardens have scope to address all three components of malnutrition – undernutrition, insufficient micronutrient and mineral intake, and overnutrition – and are therefore suitable approaches where obesity and undernutrition both present a public health problem and where other conditions (such as space and infrastructure) are conducive to gardening (Weinberger 2013). Home gardens are often the domain of women who traditionally have the role of family food providers. A focus on home gardens can thus provide an entry point towards better nutrition in several ways: by making available nutritious foods, by providing (surplus) produce for the market and thus opportunities to earn cash and by raising the awareness of women of safe processing and use of the produce. An added benefit is the protection of genetic diversity and in situ conservation of local crops through home gardens (Trinh et al. 2003). Community gardens, such as school, neighbourhood, hospital or prison gardens often combine the production of food with an educational component. Weinberger (2013) elaborates how home and community gardens can effectively contribute to social, economic and environmental development.

The country reviews collated in Virchow (2013) provide several examples where home and community gardens provide an entry point for better nutrition, with the most prominent being the successful household food production project that the international NGO, Helen Keller International (HKI), has implemented since the early 1990s in several Asian countries, including Bangladesh, Philippines and Cambodia. There is evidence that small children in households participating in gardening activities in Bangladesh increased vitamin A intake from fruits and vegetables 3-fold (Iannotti et al. 2009) and that improved night vision amongst the children could be related to improved nutrition (Talukder et al. 2010). The project also led to a 48-percent increase in the consumption of eggs, a rich source of bioavailable, pre-formed vitamin A.

These observations support a common expectation that the production of a diverse range of crops and small animals will increase home consumption of vitamins and minerals, which in turn is expected to automatically improve the nutritional status of household members. However, whilst links between the availability of agrobiodiversity in the fields and consumption of diverse foods have been established, it is much more difficult to find a direct link between agrobiodiversity at the home level and health and nutrition outcomes (Figueroa et al. 2009; Termote et al. 2012) although isolated studies making this link exist (e.g. Remans et al. 2010). Recent reviews, cited by Weinberger (2013), conclude that it is often the design and lack of statistical power of the experiments that prevent conclusive interpretation of the data (Masset et al. 2012; Girard et al. 2012).

Home-production of food in urban areas is seen as a particularly powerful means to support healthy eating by consumers who often cannot afford to buy nutrient-dense food. Urban agriculture is an increasing activity for various groups with different backgrounds and objectives, and is specifically of importance for low income groups with regard to the provision of nutritious food items (Gerster-Bentaya 2013). Zezza and Tasciotti (2010) observed, in a review of representative household survey data for 15 developing or transition countries, that urban households engaged in farming activities tend to consume greater quantities of food (sometimes up to 30 % more) and have a more diversified diet, as indicated by an increase in the number of food groups consumed. A relatively higher consumption of vegetables, fruits and meat products compared to the same economic groups translated into an overall higher calorie availability as well as higher energy intake. However, challenges to urban gardening include polluted production areas (disused industrial sites, empty plots in high-density housing areas, near highways with heavy traffic), use of waste water for irrigation (danger of contamination with bacteria, pesticides, heavy metals) and environmental hazards (lack of sanitation in animal keeping, spraying of pesticides in densely populated areas). Urban agriculture will only have a chance if its multifunctional potentials for production, social inclusion, income generation as well as leisure and provider of ecosystem services are recognized within the context of urban development and liveable cities (Gerster-Bentaya 2013).

Processing and Marketing

Sustainable production is complemented by safe processing for home consumption, storage or sale. Processing is a means for increasing the shelf life of food, its palatability or digestibility, its transportability or its availability to certain consumer groups. Through food processing, both at home and industrially, the (nutritional) value of the produce can be increased and postharvest losses can be reduced, although there may also be nutrient losses during processing (Hawkes and Ruel 2012).

Food fortification is a specific form of processing with the aim of improving the nutritional value of food; often staple foods are fortified because these foodstuffs are widely available and consumed and thus provide a good means to reach all groups within society. Examples include iodized salt, vitamin A-enriched vegetable oils and iron-enriched breakfast cereals. Food fortification is sometimes seen as a less sustainable approach than the promotion of a diverse diet but it is also promoted as necessary and cost-effective in situations where access to non-staple food is difficult for poor or sick people (Keding et al. 2013; Rahman and Islam 2013).

Although marketing – besides processing – may not strictly belong to “agriculture” it is part of the food chain and entails opportunities to foster nutrition-sensitive agriculture. There are two distinct aspects to marketing regarding the provision of nutritious food to consumers, be it locally or internationally: first, the existing markets for declared and certified healthy and nutritious food. They provide consumers with access to high-quality produce and products and also provide incentives to producers and processors to supply such goods (generally through higher prices compared to similar products with less nutritious value). The second aspect is that of empowerment of specific groups by providing them with cash earning opportunities along and beyond the entire food chain. Although direct links between increased income and improved nutrition remain controversial (Birkenberg 2013), there is some evidence that cash income can provide certain consumer groups with the flexibility to purchase quality food to which they otherwise would not have access and thus add nutritional value to their diets.

Market instruments, such as premiums for specific nutrient content, can also be employed to stimulate the nutritious quality of production and processing. This is already common in many countries for industrially processed goods, such as premiums on fat and protein content in milk, protein content of bread, wheat or brewing barley but – to the knowledge of the authors – so far has not been reported widely for vitamins and minerals. Despite not being in the core of the nutrition-sensitive agricultural approach, other quality criteria attributed to ecological and safe production and processing, as well as other social and ethical standards, could influence the nutritional status of consumers and hence be relevant.

McLachlan and Landman (2013) provided an overview on the market structure in South Africa. Four supermarket chains cover 90 % of the corporate retail sector, which makes up between 55 and 68 % of the food market. Supermarkets ensure the availability of high quality produce at low prices, because of the large volumes of produce they are able to procure and sell. This benefits poor consumers. However, small-scale producers and small processing enterprises are disadvantaged, because they cannot guarantee the quality, safety standards, volume or consistent supply required by supermarkets. In addition to supermarkets, alternative marketing channels are being discussed to address this issue, such as farmers' markets or vegetable box schemes. Extension and training to improve the quality and productivity of small-scale farmers' production and to strengthen marketing cooperatives through which small-scale farmers are able to improve their market access and increase their bargaining position are also used.

An example of the combination of public incentives for smallholder production and improved nutrition is the food procurement programme (PAA) in Brazil. It operates along the entire food chain, including the specification of procurement options. This example is particularly interesting as it operates on a large scale. Significant benefits are presented to producers and retailers because the government scheme guarantees demand and thus offers the participants security in forward planning. Another important aspect of this on-going programme is that it has already stimulated the diversification of food production and the conservation of biodiversity by supporting regional food production and consumption (Maluf et al. 2013).

Baast (2013) elaborated on the imperfection of markets in Mongolia, where increased demand does not always automatically lead to increased supply. Interventions were necessary to lower the risk of production, for example by assisting animal herders with insurance schemes and farmers with the setting up of small-scale dairy farms, which reduced the risks of production and provided a more constant supply of nutritious food to consumers.

Recommendations

The reviews prepared for this desk study and analysis of significant literature led to the following recommendations, directed at development professionals. These recommendations should help to put a specific nutrition lens on agricultural research and development projects or programmes. As mentioned above, nutrition-sensitive agriculture takes a systems approach and links sectors and intervention levels, while aiming to deliver nutrient-rich and balanced diets to all consumers (Fig. 1). Although the entry points will always be context-specific, guidance is provided for project design and implementation by outlining possible general entry points. In this context it is important to note that – although the system works best when all factors are in place – small and important changes can well happen at local scale by working on one or two entry points. The current lack of a comprehensive supporting framework for nutrition-sensitive agriculture in most countries should not lead to inactivity.

Entry point “Enabling policies”

-

The Human Right to Adequate Food, including the Human Rights Principles (i.e. transparency, empowerment, participation, accountability), should be given strong consideration, and any policies affecting nutrition should routinely be subjected to human rights assessments prior to as well as after their implementation.

-

Incentives for improved quality, productivity, diversity and competitiveness of domestic agricultural production should be targeted more clearly towards nutrition aspects.

Entry point “Mechanisms for collaboration”

-

In order to support relevant projects and programmes, public and private funding organizations should set up funding streams that focus on nutrition-sensitive agriculture and target the various aspects of food and nutrition security and the relevant impact pathways in a systemic way. Appropriate guidelines and incentives should be provided to foster sustainable institutional partnerships.

-

Because of the multi-dimensional aspect of nutrition-sensitive approaches, collaboration across line ministries and authorities is a crucial element of success. It is recognized that the coordination amongst sectors can create difficult discussions and decisions as it involves political trade-offs in budgetary processes. Mechanisms and space thus need to be created that allow for such discussions to take place and that foster joint planning, programming and evaluation.

Entry point “Awareness and capacity”

-

Conservation, use and further development of agrobiodiversity as a basis for food and nutrition security worldwide is an issue that should be in the responsibility of society as a whole. It is not an issue to be left to single actors. Therefore, broadly implemented and coordinated public awareness schemes could stimulate and support local or regional initiatives that are active in this field.

-

Awareness should be raised amongst all, from the people affected by food and nutrition insecurity to those who can make decisions for large-scale change, about specific nutritional aspects. This also includes capacity building at all levels of the agro-food system as well as strengthening the extension sector.

-

Studies and projects need to be designed so that meaningful data and knowledge can be generated. This also includes relevant monitoring and evaluation processes, which should be built into research, and development programmes from the outset. Findings should be clearly communicated to policy-makers, consumers and other stakeholders in order to support advocacy.

Entry point “Focus on appropriate beneficiary groups”

-

The complexity of gender dynamics within households and their central role in the agricultural and non-agricultural economies need to be acknowledged. Therefore, nutrition-sensitive agricultural interventions must take into account the specific needs of the individual household members to be successful. This includes gender-oriented participatory extension approaches such as household and couple approaches.

-

School feeding programmes hold great promise for connecting nutrition-sensitive agriculture/gardening with nutrition education. These and other food assistance programmes should be expanded and designed in a way that integrates local producers and provides local incentives for the production of healthy and nutritious food.

Entry point “Elements of the food chain”

-

Nutrition-sensitive agriculture needs to operate along the entire food value chain and it is crucial that the concept of "the food value" chain incorporates nutritional values and – where applicable – health values.

-

Home and community gardens play an important role in producing nutritious food directly where it is needed but they also have limitations due to prevailing opportunity costs (e.g., where space and time for production is limited). Gardening activities should thus be critically assessed and only supported where appropriate.

-

Value chains that foster the inclusion of smallholders, small-scale processors and service providers need to be strengthened as these have the potential for the provision of consumers with sufficient and nutritious food at affordable prices, and additional income generating opportunities, especially for women.

-

The use of traditional or “underutilized” crops and animal breeds should be considered as nutritious alternatives and additions to improved varieties of staple crops and breeds. Doing so could strengthen local agro-food systems and make them better able to cope with climatic changes while at the same time maintaining traditional knowledge and strengthening local cohesion.

-

Where they exist, legal obstacles to widespread use of seed of local and improved crop varieties need to be removed in order to provide a basis for widespread adoption and use of nutritionally valuable crops.

-

A major effort should be made to survey food availability and food consumption on a regional level, based on clearly defined and accepted indicators, in order to track progress and be able to provide tailor-made solutions to fill (seasonal) nutrition gaps for specific regions and specific user groups.

Conclusions

Sustainable strategies for a nutrition-sensitive agriculture and for food-based approaches to improve the nutrition and health status of poor people require the incorporation of explicit nutritional objectives into agriculture, health, education, economic, environmental and social protection policies.

The production of nutrient-rich fruits, vegetables and grains and the keeping of small animals have proved in many of the reviews underlying this synthesis paper to have a clear effect on the consumption patterns of participating families as a step towards better nutrition. In addition, the most successful programmes and projects have an integrated food chain approach, linking capacity development for the safe production of healthy food with the development of short value chains that foster local procurement. Finally, processing and transport infrastructures are particularly important where production and consumption areas are further apart, such as is often the case in urban settings, to ensure that food quality is not compromised. These programmes are also highly collaborative and bring together stakeholders from the policy, research and development arenas.

The reviews further confirm that nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches can support particular groups within society, such as communities and households that are at risk of malnutrition, without making them dependent on government hand-outs. Children are in the focus of school gardening programmes where the production of nutritious food can be combined with educational efforts to raise awareness of the links between agriculture and nutrition, and where directions for healthy eating can be set for future generations.

However, the focus of many such programmes on self-help capacities and actions directed towards vulnerable groups, such as tribal groups, women, elderly and sick people, should not lead to disregard for the deeper causes of hunger and malnutrition: seed packages for home or community gardens cannot be the right answer if women generally lack access to land, employment, health services and education. Thus, many such initiatives can become part of a strategy for nutrition-sensitive agriculture, but the overall and multidimensional analysis of nutritional problems in a society nevertheless needs to be approached on a broader political scale.

The particular strength of nutrition-sensitive agriculture is that it paves a way for making a multidimensional approach to improving food and nutrition security of vulnerable people a reality, and putting it into practice. Single measures proposed in this paper have been identified and implemented previously, but measuring investment in agricultural production or food value chains against individual people’s nutritional outcomes (instead of other criteria such as monetary return on investments) is something new. In this sense, nutrition-sensitive agriculture sets improvements regarding the nutritional, social and health status as the “ultimate standard” against which any actions taken have to prove their effectiveness. This concept is thus highly convergent with the Right to Food and the strategic guidelines of national and international development policies for enhancing food and nutrition security in various action fields.

However, measuring agricultural investments against people’s nutrition status is limited by methodological difficulties and proving that the efforts and initiatives described above have a positive influence on the health status of people is hampered by a lack of clear evidence. Although there is a host of anecdotal evidence, statistically valuable datasets are rare. In order to promote nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches more forcefully, rigorous monitoring and impact evaluations need to be included in research and development programmes at all levels.

The paper has also highlighted the current fragmentation in approaches towards more nutrition-sensitivity in agriculture. Although awareness of the need for collaborative approaches is rising, the reality is that sectors are usually operating in isolation from one another, thus missing important opportunities, e.g. for establishing innovative agriculture-nutrition/health linkages. Where national coordination offices have been created, joint projects are more visible and as a whole more successful.

Together with other global developments, such as population growth, income structures and dietary changes, the effects of climate change put enormous pressure on agricultural systems with knock-on effects into other areas, as seen in the 2008 food price crisis. The authors believe that there is a need for a paradigm change away from grain cropping in monocultures towards more diverse production systems that include locally developed and locally adapted crop and animal varieties and locally adapted input methods so that more options are available. Substantial capacity strengthening will be required in order to implement and assess these options.

Although nutrition-sensitive agriculture is a cornerstone of improved nutrition and better health of consumers in general, and of vulnerable groups in particular, it is important to recognize that the approach of nutrition-sensitive agriculture on its own will not solve the problem of malnutrition worldwide. While in the agricultural sector awareness needs to be raised for more nutrition-sensitive value chains from production to storage, processing and consumption, close interaction with initiatives in the other sectors involved (health, environment, education, etc.) is essential for jointly addressing the severe threat from micro-nutrient deficiency.

References

Baast, E. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture in Mongolia: old paradigms and new challenges. A case study. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Beuchelt, T. (2013). Can nutrition-sensitive agriculture be successful without being gender-sensitive? A human rights perspective. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Birkenberg, A. (2013). Market integration, smallholders and nutrition: A review. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Burlandy, L., Rocha, C. & Maluf, R. (2010). Integrating nutrition into agricultural and rural development policies: the Brazilian experience of building an innovative food and nutrition security approach. Paper presented at the International Symposium of Food and Nutrition Security, FAO, Rome, December 7–9 2010.

CFS (2012). Coming to terms with terminology. Revised Draft 25th July 2012. Committee on World Food Security.

Christinck, A. (2013). Plant breeding for nutrition-sensitive agriculture – an appraisal of developments in plant breeding. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Curralero, C. B. & Santana, J. A.(2007). The Food Acquisition Program in the South and Northeast Regions. In: Vaitsman, J. & Paes-Sousa, R. (Eds.) Evaluation of MDS Policies and Programs—Results. Vol. 1, Food and Nutritional Security. Brasilia: Secretariat for Evaluation and Information Management Ministry of Social Development and the Fight against Hunger.

Dans, A., Ng, N., Varghese, C., Tai, E. S., Firestone, R., & Bonita, R. (2011). The rise of chronic non-communicable diseases in southeast Asia: time for action. The Lancet, 377(9766), 680–689.

Darith, S., & Sopheap, S. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture in Cambodia (A case study. Chapter in: Virchow, D. (Ed.) Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health). Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Fan, S., & Pandya-Lorch, R. (Eds.). (2012). Reshaping Agriculture for Nutrition and Health. An IFPRI 2020 book. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

FAO. (2012a). The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2012. Economic growth is necessary but not sufficient to accelerate reduction of hunger and malnutrition. Rome: FAO.

FAO (2012b). Synthesis of Guiding Principles on Agriculture Programming for Nutrition. Draft September 2012. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome. www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/wa_workshop/docs/Synthesis_of_Ag-Nutr_Guidance_FAO_IssuePaper_Draft.pdf

Figueroa, B. M., Tottonell, P., Giller, K. E., & Ohiokpehai, O. (2009). The contribution of traditional vegetables to household food security in two communities of vihiga and migori districts, Kenya. Acta Horticulturae, 806, 57–64.

Gautam, R., Suwal, R., & Sthapit, B. R. (2009). Securing family nutrition through promotion of home gardens: underutilized production systems in Nepal. Acta Horticulturae, 806, 99–106.

Gerster-Bentaya, M. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive urban agriculture. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Girard, A. W., Self, J. L., McAuliffe, C., & Olude, O. (2012). The effects of household food production strategies on the health and nutrition outcomes of women and young children: a systematic review. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 26(s1), 205–222.

Hawkes, C. & Ruel, M.T. (2012). Chapter 9 (pp. 73–81) in: Fan, S. & Pandya-Lorch, R. (eds) 2012. Reshaping Agriculture for Nutrition and Health. An IFPRI 2020 book. IFPRI. Washington, DC.

Headey, D., & Fan, S. (2010). Reflections on the Global Food Crisis. How Did It Happen? How Has It Hurt? And How Can We Prevent the Next One. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

Hotz, C., Loechl, C., de Brauw, A., Eozenou, P., Gilligan, D., Moursi, M., et al. (2012). A large-scale intervention to introduce orange sweet potato in rural Mozambique increases vitamin A intakes among children and women. British Journal of Nutrition, 108, 163–176.

Iannotti, L., Cunningham, K., & Ruel, M. (2009). Diversifying into healthy diets (Homestead food production in Bangladesh. pp. 145–151 in. Millions fed - Proven successes in agricultural development). Washington, DC: IFPRI.

IFPRI (2011). Agriculture for improved nutrition and health. A revised proposal submitted to the CGIAR Consortium Board by IFPRI on behalf of [11 further CGIAR Centres]. October 2011. www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/crp4proposal_final_oct06_2011.pdf. Accessed 30 January 2013.

Jaenicke, H., & Azam-Ali, S. (2009). Crop diversity as a contribution to building resilience. Presentation made at the CGIAR Science Forum. The Netherlands: Wageningen.

Jeddere-Fisher, K., & Kheang, K. M. (2011). Independent mid-term evaluation of the “Joint program for children, food security and nutrition in Cambodia”. New York: MDG-F Secretariat.

Kahane, R., Hodgkin, T., Jaenicke, H., Hoogendoorn, C., Hermann, M., Keatinge, J.D.H., d’Arros Hughes, J., Padulosi, S. & Looney, N. (2013). Agrobiodiversity for food security, health and income. Agronomy for Sustainable Development Article 147. doi:10.1007/s13593-013-0147-8.

Keatinge, J. D. H., Waliyar, F., Jamnadass, R. H., Moustafa, A., Andrade, M., Drechsel, P., et al. (2010). Re-learning old lessons for the future of food – By bread alone no longer: diversifying diets with fruit and vegetables. Crop Science, 50, 51–62.

Keding, G., Schneider, K., & Jordan, I. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture as a key concept for sustainable diets: challenges in production, processing and utilisation of foods. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Lahiff, E., Davis, N. & Manenzhe, T. (2012). Joint ventures in agriculture: Lessons from land reform projects in South Africa. London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

Low, J., Kapinga, R., Cole, D., Loechl, C., Lynam, J. & Andrade, M. (2009). Challenge Theme Paper 3: Nutritional Impact with Orange-Fleshed Sweetpotato (OFSP). CIP Social Sciences Working Paper 2009 (1).

Maluf, R. S., Burlandy, L., Santarelli, M., Schottz, V., & Speranza, J. S. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture in Brazil. The Brazilian experience in promoting food and nutrition sovereignty and security: contributions to the debate on nutrition-sensitive agriculture. A case study. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Masset, E., Haddad, L., Cornelius, A., & Isaza-Castro, J. (2012). Effectiveness of agricultural interventions that aim to improve nutritional status of children: systematic review. British Medical Journal, 344, 1–7.

McLachlan, M., & Landman, A. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture in South Africa: a case study. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Msiska, F. B. M. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture in Malawi; a review of innovative approaches, opportunities and challenges. A case study. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: ood Security Center.

Popkin, B. M. (2001). The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world. Journal of Nutrition, 131(3), S871–S873.

Quisumbing, A. R. (Ed.). (2003). Household decisions, gender and development: a synthesis of recent research. DC: IFPRI. Washington.

Rahman, K. M. M., & Islam, M. A. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture in Bangladesh. A case study. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Reddy, K. S., & Katan, M. B. (2004). Diet, nutrition and the prevention of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Public Health Nutrition, 7(1A), 167–186.

Remans, R., Flynn, D. F. B., DeClerck, F., Diru, W., Fanzo, J., Gaynor, K., et al. (2010). Exploring new metrics: Nutritional diversity of cropping systems. In B. Burlingame & S. Dernini (Eds.), Sustainable diets and biodiversity. Directions and solutions for policy, research and action (pp. 134–149). Rome: FAO.

Roos, N., Wahab, M. A., Chamnan, C., & Thilsted, S. H. (2007). The role of fish in food-based strategies to combat vitamin a and mineral deficiencies in developing countries. The Journal of Nutrition, 137, 1106–1109.

Sage, C. (2012). The interconnected challenges for food security from a food regimes perspective: Energy, climate and malconsumption. Journal of Rural Studies. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.02.005. Accessed 17 April 2012.

SUN. (2010). Scaling-up nutrition. A framework for action. First Edition.(September 2010).

Talukder, A., Haselow, N.J., Osei, A.K., Villate, E., Reario, D., Kroeun, H., SokHoing, L., Uddin, A., Dhunge, S. & Quinn, V. (2010). Homestead food production model contributes to improved household food security and nutrition status of young children and women in poor populations. Field Actions Science Reports [Online], Special Issue 1.

Termote, C., Bwama Meyi, M., Dhed’a Djailo, B., Huybregts, L., Lachat, C., Kolsteren, P. & Van Damme, P. (2012). A biodiverse rich environment does not contribute to a better diet: a case study from DR Congo. PLoS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030533

Thompson, B. & Amoroso, L. (2011). Combating Micronutrient Deficiencies: Food-based Approaches. FAO and CABI.

Trinh, L. N., Watson, J. W., Hue, N. N., De, N. N., Minh, N. V., Chu, P., et al. (2003). Agrobiodiversity conservation and development in Vietnamese home gardens. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 97, 317–344.

UNHCHR (2010). The Right to Adequate Food. Human Rights Fact Sheet 34. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet34en.pdf. Accessed 8 February 2013.

Virchow, D. (Ed.). (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: a pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Weinberger, K. (2013). Home and community gardens in Southeast Asia: potential and opportunities to contribute to nutrition-sensitive food systems. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

World Bank. (2009). Gender in agriculture sourcebook. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yordy, C., & Laamrani, H. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture in Egypt. Household level food choices in Upper Egypt: from cereal subsidies to household gardens. A case study. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Center.

Zamora, O. B., de Guzman, L. E. P., Saguiguit, S. L. C., Talavera, M. T. M., & Gordoncillo, N. P. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture in the Philippines. A case study. Chapter. In D. Virchow (Ed.), Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health. Stuttgart: Food Security Cente.

Zezza, A., & Tasciotti, L. (2010). Urban agriculture, poverty, and food security: empirical evidence from a sample of developing countries. Food Policy, 35(4), 265–273.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Sector project Agricultural Policy and Food Security of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH for the desk study “Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A pillar of improved nutrition and better health” and the contributions of the team of invited experts in developing the study.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaenicke, H., Virchow, D. Entry points into a nutrition-sensitive agriculture. Food Sec. 5, 679–692 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-013-0293-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-013-0293-5