Abstract

Many Africans are presently confronted with nutritional insecurity as their diets are often deficient in essential vitamins and minerals owing to lack of sufficient consumption of fruit and vegetables. This results from problems of availability, affordability and lack of knowledge. There has been a substantive, long-term underinvestment in research and development of the horticultural sector in Africa with particular reference to those indigenous crops which are naturally high in nutritious vitamins and minerals. Lack of breeding effort, ineffective seed supply systems and an inadequate information, regulatory and policy framework have all contributed to the widespread occurrence of malnutrition on the continent. However, public sector research, development and policy amelioration efforts supported by a nascent private seed supply sector are now showing progress. Many new, improved, nutrient-dense indigenous and standard vegetable varieties are being released for which small-holder farmers are finding growing markets in both rural and urban settings. If such developments continue favourably for the next decade, it is expected that progress towards a reduction in poverty and malnutrition in Africa will be marked.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the midst of a worldwide recession and a phase of rapid price increases for agricultural commodities (Fan and Rosegrant 2008), Headey (2011) has projected that the number of undernourished people globally may now have surpassed 1 billion and the overall numbers of malnourished people globally may well exceed 2–3 billion (FAO 2009). Despite modest recent achievements in warding off hunger in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) through the provision of high-yielding staples, food demand has continued to outpace supply.

Unfortunately, the carbohydrate-rich staple crops relied upon by African consumers are often deficient in micronutrients essential for good human health, particularly vitamins A, C and E and iron, zinc and iodine. Increasingly therefore greater numbers of SSA’s population are experiencing malnutrition—an increase in their fruit and vegetable consumption would increase their opportunity to achieve a properly balanced diet. Keatinge et al. (2011) have made the case that the increasing lack of vegetable consumption worldwide is having a seriously deleterious effect on human health and that the likely attainment of many of the Millennium Development Goals is severely affected by this trend. This is demonstratively the case in SSA where under-nutrition and lack of fruit and vegetable consumption substantively affects children’s health and is a powerful contributor to child stunting and mortality. Additionally, diets containing amounts of carbohydrate that are excessive for good health are increasingly challenging adult populations in Africa with obesity and the concomitant risks of illness and premature mortality through serious non-communicable diseases such as type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Hossain et al. 2007).

A study on the patterns and determinants of dietary micronutrient deficiencies in the rural areas of East Africa showed that starchy staples provide somewhat more than 70% of the calorie intake of farmers in Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania (Ecker et al. 2010). This fact alone implies that sources of important micronutrients (such as fruit and vegetables) are not being consumed in sufficient amounts to provide the necessary vitamins and minerals for good health. A paradigm shift is now needed to examine the drivers and constituents of food insecurity not only as stand-alone entities, but also as part of an integrated framework with nutritional security to explore how livelihood adoption strategies can lead to better future strategies for poverty alleviation. This exemplifies the need for current global efforts on the biofortification of staples with micronutrients (Bouis et al. 2011) to be seen as fully complementary with the vegetable-based attempts to overcome malnutrition as advocated by this paper.

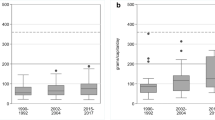

Vegetables are a vitally important source of micronutrients, fibre, vitamins and minerals and are essential components of a balanced and healthy diet. Yet, in most developing countries in Africa, production is still too low to provide their populations with even the minimum per capita consumption of 200 kg/person/year required for good health (Ali and Tsou 1997). In SSA, only 43% of this requirement is met which itself is difficult to comprehend as vegetables are clearly a major potential source of cash income for small-holder farmers and offer a much more effective way for subsistence farmers to grow themselves out of poverty than growing starchy staples alone (Chadha and Mndiga 2007).

Furthermore, plant breeding technologies and related sciences are now available to develop improved nutrient-rich and health-promoting vegetable varieties that can be consumed with major staples to provide better balanced diets and more piquant cuisines. Such an integrated dietary-driven approach will then counter the natural tendency to seek high yield and low production costs and instead select for better overall human nutrition. An example amongst vegetables bred for high yields and profits can be found in cabbage, which has a very long breeding/selection history that has produced several disease-resistant and high yielding varieties, but which offer very little in terms of nutritional content for improved human health (Keatinge et al. 2011). Davis and Riordan (2004) have claimed that reduced nutrient content is a long term historical trend in vegetable breeding which has instead been aimed at market considerations such as improved shelf-life (Sands et al. 2009).

AVRDC—The World Vegetable Center is the world’s leading international nonprofit research and development institute committed to alleviating poverty and malnutrition in developing countries through increased production and consumption of nutritious and health-promoting vegetables. It maintains the world’s largest public sector vegetable genebank, with a particular focus on hardy traditional vegetables important as food for the poor as well as wild relatives of common vegetables. Since 1992, its Regional Center for Africa, located in Arusha, Tanzania has been instrumental in breeding improved varieties of introduced and traditional vegetables such as ‘Tengeru 97’ and ‘Tanya’ tomato varieties (Solanum lycopersicum) and ‘DB3’ African eggplant (Solanum aethiopicum) for uptake and commercialization by private seed companies (Ojiewo et al. 2010a). The Center trains farmers, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, and other public sector partners in good production practices and vegetable seed systems to produce varieties that exhibit desirable nutritional and health promoting attributes in numerous African countries.

In this paper we discuss the constraints, complexity and positive contributions that the research, development and production of vegetables from both the public and the private sectors in partnership can make in addressing food and nutritional security in SSA and the mentoring role which AVRDC has continued to play in this regard in the region over the last 20 years and will continue to do so into the future.

Approaches to addressing malnutrition in SSA

The importance of simultaneous availability of multiple micronutrients

While efforts to alleviate hunger (undernourishment) require provision of food with sufficient energy (calorific) content, addressing malnutrition requires the provision and consumption of appropriate amounts of food that contains all essential nutrients required for a balanced diet. Consequently, the importance of simultaneous multiple micronutrient deficiencies on health in developing countries is gaining recognition. This is prompted by the disappointing responses often observed with single micronutrient supplements promoted by recent public health interventions to address malnutrition such as fortification of flour with iron and twice-yearly supplementation of pre-school children’s diets with vitamin A capsules.

Consequently, there is increasing emphasis on food-based approaches: biofortification and diet diversity. Biofortification uses plant breeding techniques to enhance the micronutrient content of staple foods and is a well-known approach that can supply micronutrients without any changes in dietary practices. The idea operates against the background in which fruit, vegetables, and animal products that are known to be rich in micronutrients are often unavailable to the poor owing to their relative expense. HarvestPlus, a Challenge Program of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) has been seeking varieties of more nutrient-dense staples since 2004 (Bouis et al. 2011).

Dietary diversification with vegetables offers a functional, complementary strategy to biofortification. It helps to provide nutritious and well-balanced diets but without the need for an extensive preliminary period of experimental plant breeding as it provides natural, readily-available nutrients in amounts adequate for promoting good health. Dietary diversification, in conjunction with nutrition education, focuses on improving the production, availability, the access to, affordability and utilization of foods with superior micronutrient density and ensuring their availability throughout the year. Besides improved nutrition, vegetables also add colour, flavour, and texture to meals, making diets based on bland, starchy staples more attractive and palatable.

Unfortunately, to date, the consumption levels of vegetables in SSA have been much lower than recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Currently, no SSA country meets the annual recommended level of consumption of vegetables and fruit (Table 1). Increased research to overcome production constraints and to revisit the cultivation of African traditional vegetables that are better adapted to prevailing environmental conditions could contribute to making these foods more available and affordable to the poor (Keatinge et al. 2011; Ojiewo et al. 2012). However, such research must also seek to reduce the consistent postharvest losses currently seen in vegetable crops and consumers must be given proper knowledge on how they can be prepared hygienically and to ensure the bioavailability of the micronutrients in the cooked dishes to be consumed.

The unique role of vegetables in ensuring food (and nutritional) security

Compared with most starchy staple crop production, evidence indicates that vegetable production is more profitable, increases employment and income-generating opportunities, and brings about increasing commercialization of the rural sector (Weinberger and Lumpkin 2007). Moreover, traditional “African” vegetables such as amaranth (Amaranthus spp., Fig. 1), cowpea leaves and pods (Vigna unguiculata), African nightshade (Solanum scabrum and S. villosum), spider plant (Cleome spp.), African eggplant (S. aethiopicum, S. anguivi and S. macrocarpon) and moringa (Moringa oleifera) are rich in micronutrients, antioxidants (Yang and Keding 2009), and other health-related phytochemicals. The antibiotic, probiotic and prebiotic properties of vegetables can restore the balance of beneficial decomposing bacteria in the digestive tract (Park et al. 2002; Erasto et al. 2004; Veluri et al. 2004). Enhanced consumption of vegetables and a greater diversity of available foods can help address the burden of chronic diseases. Increased fruit and vegetable consumption also has been widely promoted for their health benefits from non-nutrient phytochemicals associated with the prevention of chronic diseases (Steinmetz and Potter 1996). For example, diets rich in micronutrients and antioxidants are strongly recommended to supplement medicinal therapy in fighting HIV-AIDS (Friis 2006).

Traditional vegetables often provide higher amounts of provitamin A, vitamin C and several important minerals than common, intensively bred vegetables [cabbage (Brassica oleracea), cucumber (Cucumis sativus) etc.], both on a fresh weight basis and after preparation (Ojiewo et al. 2010a). Lin et al. (2009) found that for an individual to meet the dietary reference intake for pro-vitamin A, it would require consumption of either 16.3 kg of cabbage or 130 g of jute mallow (Corchorus spp.). AVRDC has identified and selected nutrient-rich vegetables among traditional and often underutilized vegetables to promote their greater use and consumption for better food and nutritional security. With usually shorter growing cycles than traditional staples, vegetables can be less affected by environmental threats such as drought. In addition, in general they require less space than staple crops and can maximize the use of natural resources when water and nutrients are scarce (Tenkouano 2011). As the growing trend in climatic uncertainty is experienced in SSA, the hardiness and drought tolerance of some traditional vegetables should become increasingly important. Interest in traditional vegetables has been growing in the region due to increased awareness of their nutritional and overall health benefits and this extends to the formulation and publication of improved recipes for their cooking and consumption (see for example, Gockowski et al. 2003; Weinberger 2007; Uusiku et al. 2010; Muhanji et al. 2011). This has raised demand for improved varieties and quality seeds. In response, the long term efforts of AVRDC have resulted in the release, for the first time in 2010, of seven new varieties of traditional vegetables in Tanzania (AVRDC 2011) and eight such new varieties in Mali (Ministère de l’Agriculture, République du Mali. 2011, Table 2).

Interlinkages between breeding and food and nutritional security

Farmers have long been producing seeds of local vegetable landraces due to spatial and temporal gaps in accessing quality seed from local markets, as private companies often have little interest in producing open-pollinated cultivars (Weinberger and Msuya 2004) which frequently results in farmers saving their own seed. Without proper seed production, processing technology, quality assurance, and management supervision, locally produced seeds by both individuals and communities are often infected by seed-borne or seed-transmitted viruses, fungi, bacteria and insects, and are genetically diverse (João 2010), thus reducing the quality of the seeds and the subsequent crops.

Kays and Dias (1995, 1996) noted that there were 392 vegetable crops cultivated worldwide while in Africa only about 20 of such crops are produced in intensive cropping systems (Siemonsma and Kasem 1994) and have thus attracted commercial breeding attention. Vegetable breeding should, at any point in time, be demand-driven to produce quality seed that meets both the social and financial objectives of African farmers while satisfying consumer tastes and preferences. Subsistence farmers typically seek varieties with good yield, disease and pest resistance, prolonged flowering for leafy-type vegetables, long seasonality of picking, uniformity and environmental stress resistance. Vendors and consumers, in contrast, look for quality, appearance, long shelf life, taste, nutritional value and affordability. Unlike most field crops, appearance and quality in vegetables is crucial. As worldwide health awareness increases and household incomes grow, increasing global demand for more nutritious and health-promoting vegetables, particularly in urban areas of SSA, is expected. Increased yields from good quality seed would increase farm household income, which is also expected to improve rural and peri-urban household purchasing power and enhance dietary diversity through consumption of other market-purchased food items.

Breeding for multiple pest resistance and abiotic stress tolerance

Vegetables are particularly vulnerable to a broad range of pathogens and insects. Effects range from only mild symptoms to catastrophic. Such biotic constraints are often difficult to control because their populations are variable in time, space and genotype (Strange and Scott 2005). Plant breeding is a tried and tested approach to manage such constraints but it remains a continuing task to retain levels of resistance owing to the constant evolution of damaging pathogen and pest species. Such plant breeding is now greatly facilitated by marker-assisted selection and yet in many traditional African vegetable species the identification of such markers is presently a very under-developed science. Consequently, there is an acute need at policy level to acknowledge the fact that plant pests seriously threaten food supplies and thus adequate and continued research resources should be devoted to their management and control. A typical constructive example is bacterial wilt resistant tomato lines recently developed by AVRDC that are currently undergoing on-farm trials by partner seed companies and public sector authorities in Eastern and Southern Africa. Options are also becoming available for combining multiple biotic and abiotic stress tolerances in single varieties and this additional complexity is a requirement from current vegetable breeding programs if robust varieties are to be produced. This required complexity of biotic and abiotic resistance can only be achieved quickly if conventional breeding is supported by molecular marker technologies and this clearly requires substantive additional modern research knowledge and investment if effective outputs and development outcomes are to occur.

Breeding for enhanced nutritional traits

Increased global emphasis on the need to combat micronutrient malnutrition (Keatinge et al. 2011) requires vegetable breeders to respond by developing nutrient-dense vegetables. These micronutrients must also be more available to be absorbed by the human body, either from consuming the fresh vegetables after food preparation, or through additional postharvest processing to enhance bioavailability. This adds a major additional set of challenges to the breeding and postharvest research process and underlines its considerable complexity if successful products are to emerge. The existence of the AVRDC genebank (the world’s largest public-domain collection of tropical vegetables now approaching 60,000 accessions and including more than 430 species of common and traditional vegetables) is a critical resource to provide the variability in traits needed for breeding programs. This is particularly true for Africa as the AVRDC collection holds the largest collection of African traditional vegetables worldwide and all lines are freely available to vegetable breeders in both the public and private sectors (Ojiewo et al. 2012). However, AVRDC’s vegetable breeding partners recognise that developing commercial varieties of crops with enhanced nutrition may come at the expense of commercially important qualities and thus may require a trade-off in what is typically known as the breeder’s dilemma (Sands et al. 2009). Informed knowledge of our partners’ diverse and variable needs in the vegetable value chain therefore becomes yet a further level of complexity in the production of AVRDC breeding program outputs but the Center recognises this to be a real-world requirement which has to be accommodated.

Vegetable breeding, seed regulatory and supply systems and policies in Africa

Vegetable breeding, seed supply systems and institutions

Vegetable breeding in the majority of SSA countries is practically nonexistent with capacity in the public sector having been severely reduced historically through lack of funding and privatisation. Vegetable seed production and multiplication systems remain beset by constraints, most importantly, access to quality seed of improved and adapted varieties. Small-holder farmers that dominate the vegetable production sector often rely on their own saved seed or seed secured through informal networks. Rohrbach et al. (2003) have estimated that less than 10% of the crop seed planted in Africa is purchased from the formal market each year. This partly stems from bureaucratic procedures associated with variety releases in some African countries (Table 3) where official trading authorization in seed requires varieties to be registered, which hinders local seed production and encourages importation, re-packing and selling of perhaps less-well adapted seed. In Tanzania, the share of seeds of traditional vegetables sold in the formal market is about 10% with only about 15 ha under formal seed production (Weinberger and Msuya 2004). Farmer saved seed and those from informal sources tend to be unreliable in terms of quality, quantity, and the varieties may not be tolerant/resistant to pests and diseases though in relative terms this seed is cheap. However, using this possibly poor quality seed takes up valuable land with crops of low potential productivity. Local seed enterprises will develop only when they can offer farmers a clear advantage over seed saving. Such advantage can take several forms, including convenience, access to superior varieties, and demonstrable seed quality. In Tanzania for example, although the majority of farmers (55 to 93%) are engaged in the cultivation of traditional vegetables, only about 11% of the total cropping area is then allocated to these crops. Their sale thus currently provides only supplemental income to farm households. Although 63% of farmers sell some traditional vegetables in the market, this produce only contributes about 14% of their household income (Weinberger and Msuya 2004; Keding et al. 2007).

Role of National Agricultural Research and Extension Systems (NARES)

Some public breeding organizations produce new vegetable varieties but in general concern is growing that the overall investment in public sector plant breeding of vegetables in SSA has severely declined to well below a functional minimum. This is particularly important for the development of new vegetable varieties to deal with regionally important pests and diseases that are not economic for private breeders to address. Sporadic efforts at evaluation and selection of germplasm of traditional vegetables have been carried out by some public sector research organizations, mostly in Eastern and Southern Africa and a few varieties have been produced (AVRDC 2008). Breeding and seed systems for traditional vegetables are, in general, better structured and developed in East and Southern Africa than in Western and Central Africa. Improvement of standard global vegetables has also been attempted, often through externally funded projects, but these require to be long term in order to be effective. In Tanzania, for example, national-level vegetable breeding is mainly done at the Horticultural Research Institute (HORTI)-Tengeru and to some extent in Sokoine Agricultural University and other agricultural research institutes. Currently, owing to lack of research investment, HORTI-Tengeru has no vegetable breeders or breeding programs, with the exception of maintaining already bred varieties. So little public sector vegetable breeding is presently done in SSA that many farmers are forced to rely on poorly yielding varieties, often imported and sometimes up to 80 years old (Keatinge and Easdown 2009).

Role of national seed regulatory systems

In view of the slow introduction of seed legislation in many countries in SSA, variety release requirements, seed certification standards, and conditions for import and export of vegetable seed are likely to remain unclear for some time. In West Africa the situation is compounded by government policies and regulations related to seed production and commercialization, which concentrate solely on field crops and do not take into account the specific technical requirements for vegetable crops, thus affecting the emergence of a strong and sustainable vegetable seed sector. Owing to the considerable diversity of vegetable crops, the vegetable seed market is very segmented and thin. In some countries such as Tanzania (Table 3), this has provided the impetus for AVRDC to provide advocacy and capacity building support aimed at facilitating strict standards for seed production and compliance with international standards and regulations for movement of seed between countries. Seed regulatory systems are based largely on individual country legislation dating from the 1990s and 2000s; however, in many cases this legislation is being improved and modified through resource and capacity development for production of formal (certified) seed. In Tanzania for example, seed certification includes quality declared seeds or truthfully labelled seed produced from the semi-informal sector. Nevertheless, although there is significant need and opportunity to facilitate a vibrant vegetable seed sector, the priority in implementation in most countries continues to be for seeds of starchy grain staples rather than for vegetable seed.

Role of private sector companies

Some international and regional seed companies based in Kenya, South Africa and to a lesser extent Tanzania have developed vegetable breeding and seed multiplication systems in support of, but often in competition with, growing numbers of local seed businesses. Most of these private seed businesses were formed as a result of reduced public sector capacity and often use public sector outputs and facilities. Few of these have developed breeding programmes and often sell uncertified seed without access to the necessary breeders or basic seed. Due to plant varietal protection rights, and the need to promote varieties with enhanced yields on farmers’ fields, most private seed and/or breeding companies prefer developing hybrid seeds rather than promoting open-pollinated improved seeds developed by international agricultural research institutes and NARES. This is not a demand-driven breeding approach, as open-pollinated varieties should ideally be able to compete with hybrids in an open market. This is exemplified by AVRDC’s two most popular open-pollinated tomato varieties in Eastern and Southern Africa, ‘Tengeru 97’ and ‘Tanya,’ for which their market demand has sometimes been so high that private seed companies have been unable to adequately forecast potential sales volumes. For other vegetables there is a growing trend for private seed companies to adopt advanced open-pollinated lines and varieties and develop hybrids from them for commercialization. Other private seed businesses are the seed merchants who focus on the import and resale of seed. Such seed material is often imported from South Africa or Europe but unfortunately cannot offer any guarantee that it is adapted to local conditions thus increasing the risks to the farmers as they may lose a substantial part of the crop due to pests and diseases or environmental issues, or the produce may not meet the needs of consumers. In contrast, Technisem, although headquartered in France, has its own seed multiplication and breeding programs in Senegal and Madagascar; it sends seed from the multiplication sites first to France for processing and packaging, then re-exports it to many countries in Africa.

Role of development Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

Development NGOs are not directly involved in vegetable breeding in Africa but several such as the Global Horticulture Initiative promote activities of institutions involved in breeding activities or work through partners throughout Africa through advocacy for improved horticulture and nutrition. Others, such as Farm Concern International (FCI) and African Farm Input Promotions (AFIP), collaborate with international and national research institutions to facilitate farmer access to seed of new and promising varieties. Some of these NGOs have supported farmer evaluation of new materials, the multiplication of farmer-selected varieties and their subsequent promotion and dissemination. It must be emphasized that NGOs need strong partnerships to effectively deliver improved seeds and modern production practices that require enhanced technology. Depending on the program goals of specific research institutions, the focus of some purely research-oriented institutions on the science of the problem and the focus of NGOs being on the delivery of the solution can sometimes lead to an unproductive conflict of interest. To this end, transparency in true partnerships are required that properly place value on both research and development outputs and outcomes.

Role of AVRDC—The World Vegetable Center

No country by itself in Africa has a major focus on vegetable production—and this is where AVRDC continues to play a vital role. AVRDC’s Regional Center for Africa, based in Arusha, Tanzania, is supported with offices located in Mali and Cameroon (until 2011 also in Madagascar and Niger which were closed due to lack of international research investment). These locations represent regional breeding units and outreach activities that are defined by the generic agroecological zones in SSA. The Center has been instrumental in breeding improved cultivars of standard and traditional vegetables that best suit the needs of farmers as well as consumer tastes and preferences. These include varieties for which integrated pest management helps to reduce pesticide input and varieties which have a longer shelf life which helps in commercialization by private seed companies to assure availability of quality seed.

AVRDC has established Innovation Platforms to foster the linkages between the many players in the vegetable value chain. For example in East Africa the Innovation Platform included the Tanzanian Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Tanzania’s Official Seed Certification Institute (TOSCI), HORTI-Tengeru, NGOs, the Tanzania Seed Traders Association (TASTA), the Tanzanian Horticulture Association (TAHA), representatives from private seed companies (Alpha Seeds and East African Seeds) and staff members from AVRDC. This Innovation Platform in Tanzania is presently chaired by the Registrar of Plant Breeders Rights of the Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives.

Managing vegetable genetic resources

The Center collects, conserves and distributes vegetable genetic resources. These resources are also subjected to systematic evaluation and characterization to identify desirable traits for enhanced food and nutritional security. Improved varieties are developed and crop management options advocated with the potential to expand eco-friendly production opportunities and meet market demand for nutritious vegetables. AVRDC’s genebank has the largest global public sector collection of tropical vegetable germplasm with germplasm being fully in the public domain and freely available to all partners. AVRDC’s genebank facilities in Arusha comprise a subset of the main genebank collection and currently consist of 4,177 accessions of vegetable species, many of these being traditional vegetables (Ojiewo et al. 2012). Conservation of vegetable accessions indigenous to tropical Africa and their evaluation for nutritional composition has been completed for more than 100 species (Yang and Keding 2009). Since 1992, improved vegetable varieties have also been one of the major success stories of AVRDC’s research and development program in the region, with thousands of seed packets having been distributed to both the public and private sector, to poor households to enable them to supplement their own nutrition, as well as to displaced or distressed individuals under the Center’s disaster relief program.

Participatory varietal selection and evaluation

AVRDC employs a participatory approach to variety selection. On-station and on-farm variety evaluations and organoleptic testing with various groups (farmers, students, NARES, NGOs, seed companies and other partners) are conducted throughout the breeding process. Seeds of advanced lines are distributed to partners for on-station, multi-locational and on-farm trials. Occasionally, logistical support is provided to seed company partners to conduct multi-locational trials following the field guidelines provided by AVRDC while at the same time adhering to the procedures of variety release and registration of specific countries. Following official variety release, seed companies may freely commercialize the variety subject to meeting the prevailing official seed certification standards. However, they are unable to claim exclusive rights to varieties that are wholly bred in the public sector. Feedback from actors along the vegetable value chain allows the Center to ensure that its vegetable breeding activities meet market/consumer demand appropriately.

Variety development involving standard vegetables focuses on tomato, onion, sweet pepper and chili pepper, with some evaluation work on cabbage at the Regional Center for Africa in Arusha. A good example of collaboration between partners in an Innovation Platform is the development and release of two tomato varieties, ‘Tanya’ and ‘Tengeru 97’ with HORTI-Tengeru. AVRDC provided the germplasm and necessary plant breeding and seed production expertise whilst HORTI-Tengeru was an active participant in the varietal release process. Ex-post variety evaluation studies show these two varieties are currently the most popular tomatoes grown in Tanzania as well as in several neighbouring countries. An impact assessment of these varieties on the livelihood of selected communities by the Tanzanian government revealed that there had been a considerable increase in area under production (81%) and in productivity (40%) and net income gains for an average producer of 21% in the 7 years after their release (Ojiewo et al. 2010a). Sixty-nine percent (69%) of farmers questioned grew the new varieties from 2002 to 2003 with the remaining 31% of respondents still growing old tomato varieties, seeds of which are principally produced outside Tanzania and imported into the country but for which disease tolerance is a major challenge (Ojiewo et al. 2010a).

Breeders and plant pathologists from AVRDC and its partners have contributed over the years by quickly and accurately identifying the causal organisms of diseases, understanding their virulence mechanisms and then providing accurate estimates of their relative severity and effects on yield. This contributes to the breeding programs that are tackling these constraints as well as feeding the necessary data into programs addressing the need for integrated crop management strategies to manage biotic and abiotic stresses. Several vegetables have been bred for resistance to such diseases that have been identified as being economically damaging. For example, two late blight (Phytophthora infestans) resistant tomato varieties, ‘Meru’ and ‘Kiboko’ were developed and released in 2007 and 2008, respectively (Ojiewo 2009; Ojiewo et al. 2010b). These two varieties produce good yields of quality tomatoes under cool wet climatic conditions, when otherwise there is total crop loss of late blight susceptible varieties. Two varieties with combined resistance to early blight (Alternaria solani) and late blight, ‘Tengeru 2010’ and ‘Duluti’ were also developed by AVRDC and have been recently released in Tanzania (Table 2) in collaboration with AVRDC’s public sector partners.

Development of vegetable production technologies to increase income

The Center has developed production manuals and leaflets that outline protocols for cultural practices on standard and traditional African vegetables. The manuals and leaflets describe varieties suitable for specific agroecological zones, sowing times, nursery preparation techniques, seedling transplanting, crop management, harvesting techniques and postharvest management. Based on earlier field experience of growing vegetables under home garden conditions and several AVRDC vegetable growing programs, a “healthy diet gardening kit” containing seeds of 18 nutritious vegetable crops was developed at the regional office in Arusha. Approximately 170 to 250 kg of vegetables can be produced from these seeds year-round on small 6 m × 6 m plots.

AVRDC researchers and farmers have worked together to develop African eggplant lines ‘Tengeru White’, ‘AB2’ and ‘RW14’ and the recently released, premium-priced, and sweet-tasting ‘DB3’ variety. These have been popularized in different countries through on-farm evaluations, demonstration plots, field days in Kenya and Tanzania, and agricultural trade fairs and shows. Breeders’ seed for these advanced lines has been distributed to partner research institutes, NGOs and seed companies for on-station testing followed by multilocation trials. Local seed companies began scaling-up seed production with research partners soon after the breeders seed was made available in an effort to fast-track the official variety release that finally took place in 2010 (Table 2). A recent study (prior to official variety release) suggests the new lines are already making a difference. The assessment of household participation in growing African eggplant in four villages in Tanzania’s Arumeru district found significantly higher incomes, particularly for women, than in villages not growing the new eggplants. A typical farmer can harvest 10–20 bags of ‘DB3’ eggplant (30 kg each) every week throughout the seven-month growing season and earn US $2,500 per hectare per year—almost twice the income possible from tomatoes (Fig. 2).

Improvement of the nutritional value of vegetables

AVRDC has identified and selected nutrient-rich lines of traditional vegetables to promote better food and nutritional security in SSA. Consumption levels of some of these nutrient-dense vegetables are still rather low, partly due to their relative bitterness. AVRDC has modified and published traditional cooking recipes and methods for popular crops such as amaranth, spider plant, African nightshade, Ethiopian mustard and African eggplant, which are now fuelling resurgence in consumption of traditional vegetables in SSA.

Poor dietary mineral bioavailability from prepared foods is a particular problem in diets based on unrefined cereals, starchy roots, and legumes, which often have high levels of inhibitors such as phytate, polyphenols, and crude fibers. Oxalate in green leafy vegetables also inhibits mineral uptake, particularly calcium. The Center has improved the nutritional value of traditional vegetables by modifying conventional recipes. These recipes have been published in leaflets and distributed to farmers directly or through partners. Using the concept of biofortication, AVRDC has developed a high beta-carotene tomato, which is being promoted in Mali and other countries in SSA. Consuming just one of these orange-coloured tomatoes can provide a person’s entire daily vitamin A requirement (Keatinge and Easdown 2009).

Capacity development

Training and building the capacity of all the players in the vegetable value chain is vital to ensure sustainable production of these crops. AVRDC has focused on this aspect which has become a major part of the Center’s work. It offers 3–6 months training and research opportunities to experienced senior scientists, graduates, and undergraduate students. While doing their research work they receive training in practical skills that will be essential in the development of their scientific careers, including disease screening, developing innovative production technologies, and using molecular tools in vegetable breeding. Training by the Center also targets progressive farmers, women’s groups, NGOs, and schools through short training courses in growing, processing, and the preservation and cooking of vegetables. Cropping patterns and schedules and vegetable growing guidelines are taught, and simple, easy-to-read production and recipe leaflets with nutritional information are distributed to farmers and their households. Training of private sector company partners includes seed production technologies and business management.

Public-private sector partnerships to link farmers to markets

To address the socioeconomic challenges along the vegetable value chain, AVRDC has actively supported the public and private sector by providing improved inbred lines that accelerate variety development, sharing the Center’s disease screening protocols, and conducting training in genetic improvement and seed production. To increase the availability of high quality seeds, location-specific alliances are best formed with those private companies capable of fulfilling the necessary breeding, selection, varietal registration, and marketing activities.

Through the Innovation Platforms, AVRDC has been instrumental in establishing collaborative networks of public and private sector stakeholders in vegetable research and development to learn from each other. These partnerships have afforded AVRDC a good understanding of the use and management of intellectual property rights and how to protect these rights to be sure the Center’s target clients are freely able to access the technologies they need. Working jointly with private and public partners and negotiating agreements has further underscored the importance of clarifying intellectual property rights beforehand to ensure an appropriate balance between public sector interests and incentives for the participating company is achieved. As part of the Center’s policy dialogue initiatives, two constraints to the rapid release of vegetable varieties were identified. These were inadequate regulatory procedures for official release and lack of access to foundation seed for the production of certifiable seeds by the private sector. These constraints were discussed at several meetings of the Innovation Platforms, notably in Tanzania, where proposed revisions to the Seed Act were submitted to the Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives for onward transmission to lawmakers. Under the stewardship of the Innovation Platform, consultations involving the TASTA, the Tanzania Agricultural Seed Agency (TASA), and TOSCI were held to resolve the issue of access to foundation seeds by the private sector. One emerging scenario is now the production of foundation seeds under license from TASA to allow supply to TASTA’s member seed companies for further multiplication into certifiable seeds. However, some issues remain to be resolved based around the private sector’s discomfort at what they perceive as a dual role for TASA, as the sole official provider of foundation seeds and then the marketer of certified seeds.

Enhancing consumption and utilization of vegetables

In the Center’s training workshops for women’s groups, participants learn improved methods for processing and cooking vegetables for maximum nutritional benefit. Often vegetables in SSA are cooked for so long that they lose most of their nutrients prior to consumption. With shorter cooking times demonstrated by the Center, workshop participants discover that food can taste better and require less fuel and time to prepare.

AVRDC collaborates with public and private sector partners such as HORTI-Tengeru and Farm Concern International (Kenya and Tanzania) to develop complementary postharvest loss prevention measures (selection of varieties with good transportation quality, shelf life and/or processing attributes, modified atmosphere packaging, packing systems, simple evaporative cooling, bicarbonate wash to control fruit decay) that are adapted to local conditions and needs to enhance consumption and utilization of vegetables for good health.

Role of national and regional seed trade associations

While expanding Africa's vegetable industry offers tremendous livelihood and health-promotion opportunities for farmers, it also presents significant challenges relating to the current policy and institutional regulatory framework. Government institutions have established Variety Release and Seed Certification Committees responsible for releasing varieties bred in the specific countries. In Tanzania for example, the committee meets once a year to release varieties which have passed the Distinctiveness, Uniformity and Stability (DUS) test and have added value in terms of productivity, adaptability, and tolerance/resistance to pests and diseases under the directive of TOSCI. National public and private seed trade associations provide a platform to address bottlenecks encountered in the seed business, and enhance farmers’ access to quality seed. Two important links then between the public and private sectors in Tanzania are TASTA and TAHA. TASTA is a trade organisation, required under World Trade Organization rules, that brings together seed traders. TAHA includes NGOs, farmers, traders, and people with an interest in vegetable production, marketing and promotion. TAHA promotes horticultural production through lobbying and advocacy, training, coordination of development projects, and representing stakeholders in various local and international fora.

There are a series of initiatives underway to facilitate the delivery of improved varieties and seed to small-scale farmers in Africa by supporting the development of regional seed markets and the establishment of viable seed companies that can serve those markets. For example, the African Seed Trade Association (AFSTA) arose out of a need to have a regionally representative body for the seed industry, which could also serve to promote the development of private seed enterprises in the region. Other notable regional bodies with similar initiatives include the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), the West Africa Seed Alliance (WASA), and the East and Southern Africa Seed Alliance (ESASA). Consistent with AVRDC’s goal to harmonize seed regulations, breed new varieties and facilitate their delivery to farmers, considerable synergy has been generated by working closely with several of such ongoing initiatives.

Future perspectives and concluding remarks

In addition to investing in research and development of vegetables, which is vital, African countries should also increase their investment in longer-term interventions such as dietary diversification, food sufficiency, and biofortification as complementary approaches to achieving global food and nutritional security. Such research and development investment must be effective to help small-holder farmers who represent the majority of undernourished and malnourished households in rural and peri-urban environments. Using a holistic and multidisciplinary approach, AVRDC has developed an array of international public goods, developed technologies that address the economic and nutritional needs of the poor, and have empowered farmers in many SSA countries to engage successfully in overcoming food and nutritional security challenges. These achievements are sustaining the increased productivity of the vegetable sector, and are being translated into greater prosperity for the rural and urban poor. In addition, they have promoted more diversified and balanced diets for low-income families, while safeguarding the environment. The active participation of vegetable industry investors and stakeholders is now needed for further promulgation of public awareness, accessibility, and use of nutritious, diverse, and health-promoting vegetables. AVRDC expects this will improve nutrition and health of both poor rural and urban consumers through greater consumption of vegetables with enhanced nutritional characteristics.

Future food and nutritional security and agricultural development aid policies should emphasize the integration of intervention efforts to increase production and consumption of health-promoting vegetables and address the chronic and emerging problems of malnutrition. Further substantial investment in vegetable breeding research based on the use of molecular markers is critical to the rapid and efficient development of more nutrient-rich vegetable varieties. Value chain enhancements built on strong public-private partnerships between research institutions, private sector seed companies, input delivery systems, and NGOs are also essential. Finally, a key need is for information systems that will inform consumers of the important role of vegetables in human nutrition and effectively link research, extension, farmers, and consumers as currently, national level statistics on vegetable production and consumption are essentially lacking in most countries in SSA. All countries in SSA must rise to the challenges outlined in this paper and thus make further positive progress through these means towards the attainment of all eight of the Millennium Development Goals.

References

Ali, M., & Tsou, S. C. S. (1997). Combating micronutrient deficiencies through vegetables - a neglected food frontier in Asia. Food Policy, 22, 17–38.

AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center. (2008). Vegetable breeding and seed systems for poverty reduction in Africa baseline study synthesis report on vegetable production and marketing (p. 33). Arusha: AVRDC.

AVRDC – The World Vegetable Center. (2011). New variety releases expand market options for Tanzania’s farmers. Fresh news from AVRDC—The World Vegetable Center pp. 1–3.

Bouis, H. E., Hotz, C., McClafferty, B., Meenakshi, J. V., & Pfeiffer, W. H. (2011). Biofortification: A new tool to reduce micronutrient malnutrition. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 32, S31–S40.

Chadha, M. L., & Mndiga, H. H. (2007). African eggplant—from underutilized to a commercially profitable venture. Acta Horticulturae, 752, 521–523.

Davis, D. R., & Riordan, H. D. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950–1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23, 669–682.

Ecker, O., Weinberger, K., & Qaim, M. (2010). Patterns and determinants of dietary micronutrient deficiencies in rural areas of East Africa. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 4, 175–194.

Erasto, P., Bojase-Moleta, G. A., & Majinda, R. R. T. (2004). Antimicrobial and antioxidant flavonoids from the root wood of Bolusanthus speciosus. Phytochemistry, 65, 875–880.

Fan, S., & Rosegrant, M. (2008). Investing in agriculture to overcome the world food crisis and reduce poverty and hunger. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Policy Brief No.3. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). (2009). FAOSTAT On-line. Rome: United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online at: http://faostat.fao.org/default.aspx [Accessed on February 09, 2010].

Friis, H. (2006). Micronutrient interventions and HIV infection: A review of current evidence. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 2, 1849–1857.

Ganry, J. (2009). Current status of fruits and vegetables production and consumption in francophone African countries - Potential impact on health. Acta Horticulturae:, 841, 249–256.

Gockowski, J., Mbazo’o, J., Mbah, G., & Moulende, T. F. (2003). African traditional leafy vegetables and the urban and peri-urban poor. Food Policy, 28(3), 221–235.

Headey, D. (2011). Rethinking the global food crisis: The role of trade shocks. Food Policy, 36, 136–146.

Hossain, P., Kawar, B., & Nahas, M. E. (2007). Obesity and diabetes in the developing world—A growing challenge. The New England Journal of Medicine, 356, 213–215.

João, S. D. (2010). Impact of improved vegetable cultivars in overcoming food insecurity. Euphytica, 176, 125–136.

Kays, S. J., & Dias, J. S. (1995). Common names of commercially cultivated vegetables of the World in 15 languages. Economic Botany, 49, 115–152.

Kays, S. J., & Dias, J. S. (1996). Cultivated vegetables of the world. Latin binomial, common names in 15 languages, edible part, and method of preparation. Athens: Exon Press.

Keatinge, J. D. H., & Easdown, W. J. (2009). Hidden hunger: Food security means balanced diets. Issues, 89, 35–39.

Keatinge, J. D. H., Yang, R.-Y., Hughes, J. d’A., Holmer, R. & Easdown, W. J. (2011). The importance of ensuring both food and nutritional security in attainment of the Millennium Development Goals. Food Security: The Science, Sociology and Economics of Food Production and Access to Food (in press).

Keding, G., Weinberger, K., Swai, L., & Mndiga, H. (2007). Diversity, traits and use of traditional vegetables in Tanzania. Technical bulletin No. 40 (p. 53). Shanhua: AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center.

Lin, L. J., Hsiao, Y. Y., Yang, R. Y., & Kuo, C. G. (2009). Evaluation of ivy gourd and tropical violet as new vegetables for alleviating micronutrient deficiency. CTA Horticulturae, 841, 329–333.

Ministère de l’Agriculture, République du Mali. (2011). Catalogue Officiel des Especes et Varietes. Tome III. Cultures maraîchères. Bamako, Mali : Ministère de l’Agriculture, Republique du Mali. pp 38.

Muhanji, G., Roothaert, R. L., Webo, C., & Stanley, M. (2011). International African indigenous vegetable enterprises and market access for small-scale farmers in East Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 9, 194–202.

Ojiewo, C. O. (2009). New late-blight resistant tomato. East African Fresh Produce Journal, Horticultural News. September/October 2009.

Ojiewo, C., Tenkouano, A., Oluoch, M., & Yang, R. (2010a). The role of AVRDC—The world vegetable centre in vegetable value chains. African Journal of Horticultural Science, 3, 1–23.

Ojiewo, C. O., Swai, I. S. Oluoch, Silué, D., Nono-Womdim, R., Hanson, P., Black, L., & Wang, T. C. (2010b). Development and release of late blight resistant tomato varieties Meru and Kiboko. International Journal of Vegetable Science, 16, 134–147.

Ojiewo, C., Tenkouano, A, Hughes J. d’A. & Keatinge, J. D. H. (2012). Diversifying diets: Using African indigenous vegetables to improve nutrition and health. In: J. Fanzo & D. Hunter (Eds.), Using agricultural biodiversity to improve nutrition and health. Earthscan publications (in press).

Park, J. C., Hur, J. M., Park, J. G., Kim, H. J., Kang, K. H., Choi, M. R., & Song, S. H. (2002). Inhibitory effects of various edible plants and flavonoids from the leaves of Cedrela sinensis on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. Journal of Food Science and Nutrition, 5, 170–173.

Rohrbach, D. D., Minde, I. J., & Howard, J. (2003). Looking beyond national boundaries: Regional harmonization of seed policies, laws and regulations. Food Policy, 28, 317–333.

Sands, D. S., Cindy, E. M., Dratz, E. A., & Pilgeram, A. L. (2009). Elevating optimal human nutrition to a central goal of plant breeding and production of plant-based foods. Plant Science, 177, 377–389.

Siemonsma, J. S., & Kasem, P. (Eds.). (1994). Vegetables. Plant Resources of South-East Asia (PROSEA) No. 8, vegetables (p. 412). Bogor: PROSEA Foundation.

Steinmetz, K. A., & Potter, J. D. (1996). Vegetables, fruit, and cancer prevention: A review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 96, 1027–1039.

Strange, R. N., & Scott, P. R. (2005). Plant diseases: A threat to global food security. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 43, 83–116.

Tenkouano, A. (2011). The nutritional and economic potential of vegetables. In World Watch Institute (Ed.), The state of the world 2011: Innovations that nourish the planet (pp. 27–35). Washington, DC: World Watch Institute.

Uusiku, N. P., Oelofse, A., Duodu, K. G., Bester, M. J., & Faber, M. (2010). Nutritional value of leafy vegetables of sub-Saharan Africa and their potential contribution to human health: A review. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 23, 499–509.

Veluri, R., Weir, T. L., Bais, H. P., Stermitz, F. R., & Vivanco, J. M. (2004). Phytotoxic and antimicrobial activities of catechin derivatives. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 10, 1077–1082.

Weinberger, K., & Lumpkin, T. A. (2007). Diversification into horticulture and poverty reduction: A research agenda. World Development, 35, 1464–1480.

Weinberger, K. (2007). Are indigenous vegetables underutilized crops? Some evidence from Eastern Africa and South East Asia. Acta Horticulturae, 752, 29–34.

Weinberger, K., & Msuya, J. (2004). Indigenous vegetables in Tanzania: Significance and prospects. AVRDC technical bulletin No. 31. Shanhua, Taiwan: AVRDC.

Yang, R. Y., & Keding, G. B. (2009). Nutritional contribution of important African vegetables. In C. M. Shackleton, M. W. Pasquini, & A. W. Drescher (Eds.), African indigenous vegetables in urban agriculture (p. 298). London: Earthscan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Afari-Sefa, V., Tenkouano, A., Ojiewo, C.O. et al. Vegetable breeding in Africa: constraints, complexity and contributions toward achieving food and nutritional security. Food Sec. 4, 115–127 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-011-0158-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-011-0158-8