Abstract

The issues of food security and its specifics in high mountain regions are often neglected in national and international science and policy agendas. At the same time, local food systems have undergone significant transitions over the past two decades. Whereas subsistence agriculture still forms the economic mainstay in these regions, current dynamics are generally characterized by livelihood diversification with increased off-farm income opportunities and an expansion of external development interventions. A case study from Ladakh (Indian Himalayas) illustrates how changes of the political and socio-economic conditions have affected food security strategies of mountain households. In the cold, arid environment of Ladakh, where combined mountain agriculture is the dominant land use system, reduced importance of the subsistence base for staple foods is reflected in current consumption patterns. Seasonal shortfalls and low dietary diversity lead to micronutrient deficiencies, a phenomenon that has been described as “hidden hunger”. This paper describes determinants of the transition of the current food system, based on land-use analyses and quantitative and qualitative social research at the household, regional and national level. It shows how monetary income and governmental as well as non-governmental development interventions shape food security in this peripheral region. Focusing on the particular example of staple food subsidies through the Indian Public Distribution System, the paper illustrates and discusses how this national-level measure addresses food security and shows the implications for household strategies. Against the background of our findings we argue that tailor-made regional policies and programmes are needed to face the specific challenges in high mountain regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Food security has been an issue of worldwide concern for many decades. With policy measures, such as the Millennium Development Goals, and economic trends, such as the global food price crises in 2008, the issue has been back to the top headlines of the media and policy agendas (e.g. FAO 2009a, b; Pinstrup-Andersen 2009). During past food price crises, the rise in staple costs has especially affected vulnerable consumers. While the broad issue of food security has generally received attention, the particularities in high mountain regions have remained neglected (Jenny and Egal 2002). This is surprising, as 30-40% of the global mountain population is affected by poverty and hunger (Messerli 2004). Food issues are essential for mountain livelihoods, given the consequences on health, production and reproduction.

Food security encompasses the dimensions of availability of, access to, and utilization of food, as the most common definition of food security in use today, adopted at the World Food Summit in 1996, states: “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (FAO 1996). Moreover, this declaration stresses the issue of diversity beyond a certain amount of food consumed. Insufficient availability of vitamins and minerals can occur due to low consumption of vegetables, fruit or meat. This phenomenon of micronutrient deficiency has been described as “hidden hunger” (Kennedy et al. 2003; Shetty 2009).

Especially in the context of mountain environments – including their general characteristics of remoteness, political marginalization, a low level of market integration and limited agrarian resource potential – hidden hunger and a pronounced seasonality in the diet are prevalent. However, exact and consistent statistical data on health and nutritional indicators in these regions are rarely available. Available data often refer to the national level or are rather estimates, aggregates or extrapolations for mountain areas (Kreutzmann 2001, 2006a). Selected studies report on acute or chronic malnutrition and reduced birth weights in high mountain environments. Other studies have highlighted nutritional deficiencies such as protein-energy malnutrition and lack of micronutrients (Jenny and Egal 2002). Frequently, case studies in these regions are based on anthropometric indices for an evaluation of a prevailing situation (e.g. for the Indian Himalayas: Dutta and Pant 2003; Dutta and Kumar 1997). Besides anthropometric measurements, dietary diversity can be used as an indicator for food security (Faber et al. 2009; Hoddinott and Yohannes 2002).

Analyses of food security in the rural South have increasingly been based on multidimensional approaches (e.g. Herbers 1998; Cannon 2002; Tröger 2004) with a focus on vulnerability and livelihood concepts (DFID 1999; Berzborn and Schnegg 2007; Scoones 2009). However, most studies centre on local actors, choosing a household perspective. External processes are frequently tackled as a ‘black box’ and not adequately integrated into analysis (de Haan and Zoomers 2005). Finnis (2007) has argued for land-use practices and adaptation strategies of local farmers to be considered as embedded in economic processes and national policies. In recent years, the interdisciplinary GECAFS (Global Environmental Change and Food Systems) project, which is conceptually based on a food system approach, has drawn attention to political, socio-economic and ecological drivers in the analysis of the functioning of food systems (Ingram and Brklacich 2002; Ericksen 2008; Ingram et al. 2010). Such integrative approaches can provide an adequate background for complex food policy (Lang et al. 2009).

Choosing a case study from the high mountains of Ladakh, this paper aims to exemplify the interplay between local household strategies and the influences of government policies and non-governmental organizations from an integrated perspective. Ladakh’s Leh district in the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir, besides often being regarded as a peripheral location, is a region of geopolitical importance and rapid socio-economic change (Beek, van and Pirie 2008; Dame and Nüsser 2008). Therefore, a food security framework for high mountain regions was developed in this study which addresses place-based and non-place-based actors, local strategies and external interventions. The approach considered actors across different geographical scales and their relevance for the different food system components (Fig. 1). Our methodological approach relied on a combination of both quantitative and qualitative social research. First, the seasonal variation of nutrition patterns and dietary diversity were assessed through the analysis of food consumption and its change over time. Against a background of micronutrient deficiencies, the relevance of local land-use and market access are highlighted. We show how household strategies are influenced by government policies and non-governmental organisations through programmes to increase agricultural production and national food price policies. Here, the focus is set on the example of the Indian Public Distribution System to illustrate the impact of development intervention programmes.

Geographical setting of the case study

The high mountain region of Ladakh is characterized by a rugged topography at an average altitude of over 3000 m. It is separated from the Indian subcontinent by the Great Himalayan Range and edged by the Karakoram Range to the North. The western and central parts are dominated by incised valleys and mountain ranges of altitudes above 5000 m, whereas eastern Ladakh is characterized by the high altitude plateau of Changthang. Scattered settlements are located at altitudes between 2600 m and 4500 m. Due to the location in the rain shadow of the Himalayan Range, average annual precipitation is less than 100 mm in the upper Indus valley (Leh). Temperatures show high seasonal variation. While mean monthly values during the coldest winter months of January and February range between −15.6°C (Dras) and −5°C (Leh), monthly averages between 17.1°C (Dras) and 23.7°C (Kargil) are reached in July and August (Archer and Fowler 2004; GoI/IMD 1967). Agricultural production is entirely based on irrigation. Channels divert melt water from glaciers and snowfields or, where topography allows, from the main rivers to the settlement and land-use oases which are located along the river courses or in side valleys.

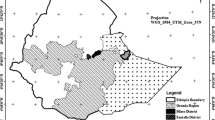

Today, Ladakh encompasses Kargil and Leh districts of the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir. The region is sparsely populated, with a total of 236 539 inhabitants in 2001 divided almost equally between the two districts.Footnote 1 Over the past decades, the region has faced a continuous increase in population. Latest census data show a yearly increase of 2.75% of total population for the Leh district between 1981 and 2001. The pace of growth is highest for the administrative capital Leh, where it accounts for an average of 5.92% over the same period of time (Goodall 2004). In 2001, Leh town accounted for 28 639 inhabitants, while the majority (88 593) of the population lived in rural settlements. Before partition and independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, the former kingdom of Ladakh had been ruled by the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir for more than a century. Ladakh, with its central market place, Leh, was a vital stop on the important trade and transit routes from the subcontinent to Central Asia (Rizvi 1999). Yet military confrontations between 1947 and 1949 due to territorial dispute over Kashmir between the young nation states of India and Pakistan changed the region’s position to an international borderland (Fig. 2) (Kreutzmann 2008; Lamb 1991). In 1962, border tensions with China escalated into military confrontation over the uninhabited Aksai Chin region. The emergence of border wars between India and Pakistan in 1965 and 1971, the Siachen conflict since 1984 (Ali 2002) as well as the Kargil crisis in 1999 expanded the region’s geostrategic significance (Aggarwal 2004). This borderland situation has resulted in massive investments in infrastructure, including the airport and road construction. Yet, for approximately half of the year, the region is only accessible by plane, as the two roads which connect Ladakh to lowland India via Srinagar or Manali remain closed for almost six months during the winter.Footnote 2

In this environment of limited agricultural resource potential, the population has sustained their livelihood on combined mountain agriculture (Ehlers and Kreutzmann 2000). Crop farming and animal husbandry together with gathering activities comprise the central pillars of livelihoods in these villages.Footnote 3 During the short agricultural season, between May and September, barley and wheat are cultivated as the main staple crops on irrigated terraces (Photo 1). These cereals are rotated with peas and sometimes mustard. In addition, vegetables – especially turnip, cabbage, potatoes, onions, carrots and green leafy vegetables – are cultivated in kitchen gardens. Single-cropping is dominant, as double-cropping is only possible below an altitude of approximately 3000 m. Wheat is cultivated in altitudes of up to approximately 3600 m (Labbal 2001 for Sabu village) to 3800 m (Osmaston 1994 for Stongde), while barley is grown at altitudes above 4000 m and up to approximately 4400 m (Osmaston 1994). Due to the climatic conditions, large forest areas are absent. Willow and poplar trees, especially along the water channels or at the margins of the arable patches, provide wood for heating, construction purposes, tools and fodder for animals. Fruit trees (especially apples and apricots) and the collection of wild herbs add to the land-use pattern. Crop farming and animal husbandry are interdependent components of the agricultural system. Livestock comprises yak, dzo (a yak and cow crossbreed), cattle, sheep and goats. Depending on the environmental resources of the settlements, animals are grazed on designated grasslands within the oases on a daily basis or at high pastures during the summer months. Alfalfa (Medicago spp.) and natural grass, grown on designated plots or margins of the cultivated area, leaves and straw fulfil the demand for winter fodder. Animal dung is used as fertilizer, animals provide draught power and transportation, and animal products are essential for the local diet (providing milk products and meat) as well as for clothing. In the absence of sufficient firewood, dung is a preferred heating source.

Methods

Empirical field work was carried out in the context of a wider research project between 2007 and 2010. The approach was based on a multilevel research perspective which allowed for in-depth information at the village level and analysis of political and socio-economic conditions.

For in-depth information on the rural settlements of Central Ladakh (Leh district), three case villages were chosen within the wider research project. This paper focuses on one of these villages - Hemis Shukpachan - which is at a 40 km distance from Leh, the district capital, and at the centre of the region. The location was selected on the basis of expert interviews and literature reviews which suggested that it is representative, most of its households practising combined mountain agriculture, albeit also having access to additional off-farm income. In March 2008, Hemis Shukpachan had a total population of 690 inhabitants. The village has mud road access and can be reached from Leh by bus once a day.Footnote 4 Basic infrastructure facilities are available, including limited access to electricity, primary and medium level schools as well as a primary health care centre.

As in other high mountain regions, exact and consistent statistical data on health and nutritional indicators in Ladakh are hard to come by. Food security in the study region has therefore been assessed through qualitative expert interviews and by comparison with questionnaire surveys undertaken in earlier studies. We focused on household food security, as intra-household food allocation differences are of minor significance in the study region. Data on characteristic food consumption from 1980 (Attenborough et al. 1994) were compared to our survey in 2008 to illustrate seasonal differences and dietary transitions over almost three decades. In 1980, Attenborough et al. (1994) surveyed standard food consumption patterns in the Zanskari village of Stongde. Based on household questionnaires (n = 30; multiple answers allowed), the relative importance of food items/dishes was established for the summer and the winter season.

For an assessment of current dietary patterns in rural Ladakh, our household survey from 2008 in the village of Hemis Shukpachan, included a section on dietary behaviour that used the same set of questions as in the 1980 study. A 24-hour recall and qualitative interviews were added for data triangulation. Questionnaire-based survey methods on food consumption do not allow the quantification of food intake. However, this tool permits detection of seasonal variation and has the advantage of combining the information of frequency of meal consumption with responses on the food preferences and dietary recommendations and 24-hour-recalls.

For the analysis of food security in Ladakh in the context of changing livelihoods and external conditions a combination of methods was chosen. At the village level, mapping of agricultural land use, standardised household interviews (n = 103) and qualitative methods were conducted. Group discussions, in-depth qualitative interviews and participatory observation that were carried out in a wider research context were used for triangulation. Where necessary, the work was supported by trained local research assistants who helped with translation and acted as contact persons. Given the research approach chosen, the analysis of non-place-based actors contributed a substantial part to the study. Therefore, thematically focused interviews with experts from government agencies and non-governmental organisations in Leh were conducted to gain information about specific aspects and dimensions of the food system. For an assessment of the market situation, a market survey in the district capital, Leh, was conducted. In addition, government documents and statistical data were accessed.

Seasonal variation in dietary patterns

In Ladakh, food consumption has primarily been based on products available from subsistence-oriented land-use and local storage facilities. Given the constraints on agricultural production, households rely on a small range of foods. Typical meals are preparations based on barley and wheat as staple crops which are combined with peas, potatoes, turnip and green leafy vegetables, some dairy products or limited amounts of meat (Table 1). Nomadic pastoralists of eastern Ladakh distinguish themselves by a higher consumption of animal products, while communities in settlement oases rely to a larger extent on barley as well as wheat (see also Rao and Casimir 2003). In the past, deficits which are grounded in the different production patterns have been compensated through barter and trade. Today, barter has a subordinate role while the majority of goods are accessed at the market (See: Access to markets in the periphery: selling cash crops, purchasing commodities).

According to expert interviews with leading doctors and high-ranking officers at the Chief Medical Office in Leh, neither persistent undernutrition nor starvation is prevalent today, yet malnutrition and subclinical undernutrition were reported. These were unanimously attributed to unbalanced diets, due to a lack of vegetables and fruit and protein-rich food items. While describing an overall situation of “rather mild malnutrition”, medical experts from the region stressed the continuing prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies including the lack of vitamin A, B6, B12 and folic acid (Interview Chief Medical Office 2008, Interview Physician 2009). The type of deficiencies varies across Ladakh due to differing dietary habits. Nomadic communities are exposed to a meat-rich diet. On the contrary, religious and social perceptions lead to a neglect of meat and cow milk consumption Buddhist communities, which was held responsible for protein-energy malnutrition and vitamin A deficiency (Interview Chief Medical Office 2008). These findings are supported by older studies, which have described micronutrient deficiencies (lack of iron, folic acid and vitamin B12); and found protein and energy deficiency was not widespread in the area (Wiley 2004 p. 60, 138; Attenborough et al. 1994 p. 403; Cvejic et al. 1997).

A general improvement of the nutritional situation was stated as follows: “A new trend has been there over the last 20–30 years: there is more awareness, horticulture and vegetable as well as fruit production have increased and socio-economic conditions have changed.” (Interview Chief Medical Office 2008). The few studies which include anthropometrical indicators for an evaluation of the situation in the study region support this evidence. Among the different indicators that rely on anthropometric data, those which evaluate the nutritional status of children below the age of six years are expected to be the most sensitive ones (Gerster-Bentaya 2009). Based on an anthropometric assessment of 477 children from the Ladakhi villages of Gya, Meeru, Igoo, Lamayuru and Wanla in 1983, Wilson et al. (1990) found 20% of the study participants to be of low weight-for-height. A study conducted by Cvejic et al. (1997) which was based on 152/198 children from Wanla area classified 53% of children below 12 months of age and more than 80% for children between 1 and 8 years as stunted (low height for age). In both surveys, the proportion of children with a critical nutritional status increased up to the age of three.

More recent studies have published data on birth outcomes. Here, the indicator of low birth weight indicated intrauterine growth retardation, which has been connected to nutritional patterns and maternal workload during pregnancy (Gerster-Bentaya 2009, Wiley 2004). For 145 hospital births in Leh in 1990, 17% of male and 37% of female Ladakhi newborns were of low birth weight (less than 2500 g; Wiley 2004). In contrast, the figures for 188 hospital births in 2006 given by Wahlfeld (2008) were 12.9% and 20.7%, respectively. As this decrease in newborns with low birth weight correlates with increased maternal mid-arm circumference, Wahlfeld suggested a change in nutritional and working patterns of the mothers.

The most striking issue, however, is the pronounced seasonality of dietary patterns. Data on standard food consumption patterns in the Zanskari village of Stongde from 1980 (Attenborough et al. 1994) showed a generally low dietary diversity with a heavy reliance on grain staples and a comparatively low level of rice consumption. Dietary patterns differed between the summer and the winter season. The availability of fresh vegetables was restricted to the summer months and imported goods ran out of stock after the closure of the passes. In general, only small amounts of rice and vegetables were consumed.

Against the background of interviews with Ladakhis who described the food patterns at that time, the findings of Attenborough et al. (1994) can be considered to reflect a situation characteristic for Ladakhi villages when subsistence-oriented agriculture was the main food source.Footnote 5 Until the beginning of the 1980s, most Ladakhis cultivated their own food and relied on the annual yields. In case of harvest failure, staples had to be borrowed from monasteries or well-off households and returned with high interest rates. Meals based on a high proportion of staples were enriched by limited amounts of vegetables available during the summer, as well as some wild herbs, fruits and sometimes meat. Rice was rarely used, and instead represented a favoured meal for festive occasions and a preferred food by families of higher social status. Elders further portrayed a situation of constraints in vegetable, rice and sugar availability and the need to skip meals in times of shortages. Product variety decreased significantly during the winter, when limited amounts of dried vegetables, stored potatoes, onions and roots as well as pulses were consumed along with staples. Likewise, Ladakhi smallholders described a general improvement over the past decades in terms of food quantity and diversity. Locals distinguished their perceived situation from the general state in “India”.

A comparison of characteristic food consumption in 1980 with our own survey in 2008 illustrated seasonal differences and dietary transitions over almost three decades. Our data depicts an increase in rice and vegetable consumption (Fig. 3). Nowadays, rice is the preferred staple during the summer months and different fresh vegetables add to the dietary pattern in this season. Results from the 24-hour dietary recall revealed that the consumption of rice tended to be underestimated, with 34% of the households having prepared a rice-based dish for lunch or dinner. However, the findings also showed a pronounced seasonality. During the winter, there was an increased consumption of cereals in the form of thukpa and paba. (For description of these and subsequently mentioned local food names see Table 1). Moreover, preferences for staple preparation changed with the seasons. While bread (tagi, including tagi khambir) and kholak were considered to be “light food” and are thus consumed between spring and autumn, paba and thukpa were considered ideal food for the winter and thought to give strength, the latter being appreciated for “heating the body”.Footnote 6 Tsampa was rarely mentioned as a meal, but rather referred to as an extra food item between meals.

Dietary patterns in the villages of Stongde 1980 (above) and Hemis Shukpachan 2008 (below). For descriptions of the various foods, please see Table 1

Today, despite the shift in dietary patterns towards more frequent preparation of rice and vegetables during the summer, the seasonality of food consumption is still remarkable. Ladakhis regarded this seasonality as the main nutritional issue. The following sections highlight the drivers of food system change and the periodic insecurities. While a variety of fresh vegetables and fruit is available from home gardens and local markets during the summer months, availability and affordability decrease in spring and autumn. As well as the availability of food through household production, the seasonal variation of dietary patterns reflects issues of market availability, caloric demands and the time required for meal preparation, both of the last two correlating with agricultural activities. By the end of the winter, when the passes to the lowland are still closed, even shops run out of stock of various products, such as eggs, milk or tea. Only those families who have members in the army that can provide them with fresh items or those who can afford the sky-high prices for plane-transported vegetables from the few traders in Leh are able to access such goods.Footnote 7 Besides land-use and markets, staple food subsidies play an essential role in the food system.

Household food strategies

Land-use change: Crop diversification and agricultural policies

Changing dietary habits are, in part, reflected in modifications of the land-use system over the past three decades. For centuries, subsistence-based mountain agriculture was the economic mainstay of the population and thus sustained local livelihoods. Products which were not produced within the household itself such as salt, tea and spices, were traded. While farming still constitutes the main pillar of food production and primary food source, land-use practices have been reconfigured (Dame and Mankelow 2010). Despite a general persistence in field structures given the limited water availability, cropping patterns have changed significantly. Farmers’ choice of cultivating wheat or barley as staples has increasingly favoured barley (Fig. 4). As wheat is easily available at subsidised rates through a government scheme (National policies: The case of the public distribution system (PDS) in Ladakh) and its yield is more risk-prone to yearly climatic variability than barley, it is becoming less popular among Ladakhi farmers. One interviewee stated: “Generally, we would produce more wheat. But here in the village, wheat doesn’t grow well and we get wheat from the ration store.” In addition, small-holders have chosen to continue the cultivation of barley due to its unavailability from the market and its cultural significance as a main ingredient of Ladakhi dishes. Moreover, certain quantities of barley are required for the production of chang, an alcoholic beverage produced by the household which is consumed and offered on many occasions.Footnote 8 The staples wheat and barley are rotated with peas, which are appreciated for their positive effect on soil nitrogen and for their taste and protein content when added to parched barley flour (tsampa).

Mustard is becoming re-established as a typical crop. Its oil is appreciated for use in lamps, women’s hair dressing and for cooking. However, the labour required for its extraction led to abandonment of the crop after the 1970s when edible oils and kerosene started to be readily available in the market. Today, farmers have begun to return to mustard cultivation owing to the introduction of oil pressing machines in the district capital, Leh. These allow the facile production of good quality oil.

The increase in preference for pulse consumption (dal, see Fig. 3) led to the introduction of lentils into the current cropping pattern. This step was fostered by subsidies for lentil seeds by the Agriculture Department. Key actors who have the goal of increasing agricultural production in the region are several government and non-governmental organisations. They influence farmer’s strategies and enhance changes in the land-use system. Their focus is on agricultural subsidies, watershed development and Hariyali (“greening”) programmes (Mankelow 2003). Government subsidies for seeds, fertilizer and machines have fostered the implementation of new inputs and technologies.

The comparison of dietary habits has shown a significant increase in vegetable consumption, especially during the summer months (Fig. 3). Interviewees pointed out that only a few households had a kitchen garden until recently and collected edible herbs from the mountains to diversify their diet. Many small-holders have started to grow a limited amount of fresh vegetables over the past decade. The range was extended from growing turnip, potato and cabbage to a variety of items including cauliflower, aubergine (brinjal), capsicum, tomato, carrots and salad. The Agriculture Department has again subsidised seeds to encourage the diversification of the vegetables grown. Another aspect clearly reflected in the changing dietary patterns is the construction of greenhouses and new storage facilities which extend the seasonal availability of vegetable products. These are supported through governmental horticulture programmes and non-governmental organisations working in Ladakh. The new technology should increase the local availability of fresh vegetables, especially during the winter months when the community relies on dried vegetables and stored roots as well as vegetable imports from the lowlands, which are sold at prohibitive prices due to air transportation costs. An increasing number of households have started to use polythene sheeting for the construction of such greenhouses. Comparatively well-off households, that can afford the cash investment, especially benefitted from the scheme. As financial assets are indispensable for programme participation, a certain number of already more vulnerable households were excluded.

Access to markets in the periphery: Selling cash crops, purchasing commodities

For mountain communities, access to markets is critical both for household consumption and trading activities. Ladakh is isolated owing to the closure of the mountain passes between November and April, which hinders the exchange of goods with the Indian lowlands. At the same time, the border situation impedes exchange with neighbouring countries. Within the region of Ladakh, the expansion of transport infrastructure and road networks is highly variable, ranging from villages on the main road, to villages with mud road access to settlements without road connection. In addition to differences in infrastructure, the institutions regulating market access are highly variable.

While agricultural production, aimed at sustaining the household’s food needs, with surpluses being bartered for food or non-food items has been traditional in Ladakh, the rise of the cash economy has created new markets. An increasing level of monetary income has led to cash availability for many mountain households and has thus made market participation possible. In recent years, a steady increase in off-farm employment has been witnessed. Data from household surveys showed that the vast majority of households (91.3% in the case of Hemis Shukpachan) had at least one member engaged in off-farm employment. Job opportunities in the administration and educational sector, wage labour employment and army recruitment as well as the booming tourism sector has led to livelihood diversification.

The region is characterised by a huge product influx from the Indian lowland. Purchasing of food and households items has become more and more relevant to Ladakhis during the past three decades. One interviewee exclaimed: “Today, everything is money, money, money.” The increase in income generation and commodification has led to re-establishment of Leh town as the main market place. Most of the larger villages have a village shop, but the range of available products remains limited. Villagers pointed out that the distance to the district capital is an important factor for decisions on purchasing activities. The shop in the village was of relatively lower importance if regular transport services were provided. For example, most inhabitants from Hemis Shukpachan preferred to travel to Leh to buy food and basic commodities. Often, such travel was combined with visits to authorities or family members. The product variety in Leh was another reason for purchasing from shops in the district capital. Food items which are frequently purchased for household consumption included tea, spices, instant soup and eggs. Several items such as meat, eggs and fresh vegetables as well as cooking gas are generally not available in the village shop. Moreover, the district capital offers a wide range of commodities from stationery and houseware to clothes. Most families fancy commodities which are considered to be ‘modern’, such as electronic devices or gas heaters. Despite these expenditures, monetary needs have risen especially due to an increase in demand for good education. As public education is often perceived to be of lower standard, interviewees spend large sums of household income for educational purposes in private schools.

Although a growing number of households have recently started to engage in commercial activities, marketing has remained on a comparatively low level until now. Our study confirmed that only a minority of households are engaged in marketing activities. For market access, different pathways were chosen. Fresh vegetables and fruit produced in kitchen gardens or on small plots were sold as cash crops at local markets. In most cases, smallholders sold their products directly, either along the main road or at the vegetable markets of the district capital, Leh (Photo 2), especially when regular transport services were available, or occasionally within the villages. Market surveys in Leh indicated that often a visit to the district capital for any other reason is used for bringing surplus products to the marketplace.

Selling of cash crops was generally restricted to surplus production. Although the availability of food from the market allowed farmers to spare part of their fields for vegetable production, cash cropping remained a minor activity compared to subsistence farming. Those who did not engage in marketing are mainly smaller households who have fewer active members involved in the labour market and thus less financial capital to replace lack of labour, or households with insufficient farm size to generate surpluses. Only few households specialised in vegetable production, adjusting it to fit market demands. This held especially true for households from Leh valley that had a member selling produce directly to the main bazaar. These households use greenhouses in springtime, allowing them to provide fresh vegetables at comparatively high prices before the opening of the mountain passes (Fig. 5).

Villagers with access to roads, proximity to army camps and main markets or inhabitants of the district capital have lower transaction costs and show a higher degree of market participation. The biggest market in Ladakh itself is the Indian Army, which is interested in local products for reducing the costs of food imports. However, this opportunity is only relevant for those settlements which are close to troop bases. In some villages, local farmer cooperatives have arranged fixed price agreements for each agricultural season and transportation costs have been provided by the army. Selling through middlemen is a rare phenomenon, few from Kashmir or Manali coming to Leh district during the summer to purchase larger quantities of selected goods.Footnote 9

Despite this general situation, attempts for broader marketing of products from the region have been made, including an experiment in flower cultivation and export in the mid 1990s (Interview Agriculture Department Leh, 2009) and recently a trial period for contract farming of potatoes.Footnote 10 Pepsi Co. India was the first (inter-)national company to introduce contracting in the region in 2007. This system has been a new possibility for some Ladakhi smallholders to gain on-farm income and to diversify livelihood strategies. Despite the fact that farmers’ expectations on yield and returns have only been fulfilled in a few cases, the majority of households have attested to their wish to continue the market-oriented cultivation of potatoes as a strategy to further diversify household income. For them, contracting facilitates market access for on-farm income generation. Yet, the international new actor in the agricultural sector – Pepsi Co. – had set targets for yields to be fulfilled for a continuation of the programme which were not met. In a local context where farmers lack alternatives for income generation from agricultural production, the benefits provided by a contract with guaranteed purchase and no transportation costs have led to a land-user’s strategy of “careful experimentation”.

The newest example for marketing of resource-based products from the high mountain region is the commercialisation of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides). The selling of sea buckthorn pulp to national and international companies has been started under the guidance of the Cooperatives Department. In 2010, the Leh declaration on the “National Sea Buckthorn Initiative” was adopted under a programme of India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests. For the next years, a vast expansion in the amount of sea buckthorn berries produced and sold has been envisaged. Government agencies hope to facilitate market access for income generation through such development programmes.

National policies: The case of the Public Distribution System (PDS) in Ladakh

Among the different development programmes implemented in Ladakh, the national Public Distribution System (PDS) serves as an example to illustrate the impact of external interventions on rural livelihoods. The PDS is one of several safety net programs in the region. It is the Government of India’s largest poverty reduction scheme and is therefore considered to be the most important economic instrument (Kochar 2005). As a system of food grain subsidies, it originates from the 1940s, when the British colonial government started to develop a food policy faced with the experience of the Second World War and the Bengal famine of 1943 (Mooij 1999a; Landy 2009). During the 1950s and 1960s, the system focused on coping with critical food shortages and price variation in urban settlements, but later expanded to rural areas. After 1964/1965, the programme has aimed at sustaining minimum prices to farmers, granting fair prices to vulnerable consumers and coping with critical food shortages (Mooij 1999a).

Programme evaluations from the 1980s and 1990s, which showed poor performance of the PDS together with an increasing fiscal deficit, led to the transformation of the scheme from a universal one into a targeted programme in 1997 (Mooij 1999c; Kochar 2005 p. 208).Footnote 11 Today, the PDS policy has three main functions: First, it promotes a price support policy and guarantees minimum procurement prices to farmers who sell food grains to the state. Second, it distributes subsidised food grains (rice, wheat flour and sugar) to vulnerable households in so-called “fair price shops”.Footnote 12 And third, it ensures food supplies at the macro level through the maintenance of food stocks.

The national government sets procurement prices at which the parastatal, Food Corporation of India (FCI), or state agencies purchase rice and wheat.Footnote 13 FCI and other agencies store the food grains and are responsible for their distribution to the states and Union Territories. Households that are accredited ration card holders are able to buy commodities from the ration stores (fair price shops). The PDS currently distributes subsidised rations to families below the poverty line (BPL), elders (Annapurna) and households classified as “poorest of the poor” (Antyodaya Anna Yojana; AAY).Footnote 14 Yet families above the poverty line (APL) can also be accredited ration card holders. Implementation of the PDS with regard to targeting schemes, additional subsidies or the diversion of food grains to the open market differs from state to state (Mooij 1999b).

The latest food price spike of 2008 illustrates the effects of the PDS. In December 2009, the press announced that “India’s food prices hit 10-year high”.Footnote 15 Between the financial yearsFootnote 16 2006/07 and 2008/09, the minimum support prices for wheat and rice rose significantly by 42.7% and 46.6%, respectively (Reserve Bank of India 2009, p. 67). During the price spike, the Indian government augmented the budget allocation for the PDS significantly, hence reducing price fluctuations and stabilizing the prices for staple crops.Footnote 17 In 2008/2009, the total offtake of wheat and rice from the central stocks under this scheme was 34,845,000 tonnes (GoI/Dept. Food and Public Distribution 2009, p.3). In that year, food subsidies released by the Indian government equalled a total of 436.68 billion rupees. During the fiscal years of 2007/2008 and 2008/2009 the annual increases in food subsidies were 31.2% and 39.7% respectively (Economic Survey of India 2009/2010, p. 204, accessed online, 11.10.2010: http://indiabudget.nic.in/es2009-10/esmain.htm).

According to Dev et al. (2004), the proportion of consumption of wheat and rice in Jammu and Kashmir state obtained from PDS to total consumption was above the Indian average.Footnote 18 In the State’s Leh district it was found to be even more significant. In 2007/2008, 23,938 households (i.e. more than 98% of the population) were holders of ration cards under the scheme. Yet in the land-based economy of Ladakh, the buying of food grains – whether from the market or under the PDS – had long been considered to be shameful for consumers “for being so poor” as one interviewee put it. Despite this unassertive beginning, the PDS is today among the most influential government schemes and the most significant with regard to food security in Ladakh. Leh district currently has over 133 ration stores with at least one in the vast majority of all villages (Fig. 6). For the year 2009/2010, a total of 465 tonnes of rice and 450 tonnes of wheat equivalent to about 1500 truck trips from the lowlands have been sanctioned for the district. This amount was still below the requirements calculated by the Department (Interview Department of Food & Supplies 2009). Given the inaccessibility of the region during six months of the year, the logistic requirements to ensure the provision of these quantities are considerable, especially in the case of road blockages during the summer months – such as in times of political unrest in the Vale of Kashmir or after floods and infrastructure damage. For example, in August 2010, the Department of Food and Supplies in Leh was facing difficulties in providing rations after roads had been cut due to massive flash floods. The situation was exacerbated by lower stocks caused by political tensions in Jammu and Srinagar which had led to road blockage earlier in the year. Moreover, additional food rations had to be distributed to people directly affected by the floods (Interview Department of Food & Supplies 2010).

Under the various categories of the PDS, a total of 106,246 beneficiaries were assigned in the district.Footnote 19 BPL and AAY households could purchase up to 3.5 kg of rice and wheat per head and month at subsidized rates and beneficiaries in the Annapurna category were granted 5 kg of rice and 5 kg of wheat free of cost each month. Our case study village in central Ladakh and its households were typical for the region: of a total of 103 households that participated in the household survey in 2008, only 11 did not buy food grains from the ration store. The 8 households that were not ration card holders mostly gave administrative problems as a reason.Footnote 20 The majority of households (70) fell under the BPL category, while some households were APL beneficiaries (17) and a few (8) were under AAY, most of the last being single-person-households. Due to the comparatively high market prices in the district, the economic incentive even for APL-households to purchase from ration stores remains high (Table 2). Thus, the vast majority of households (89.3%) in the study village accessed the ration store for the fulfilment of their food requirements. Interviewees ranked food acquisition from the ration store second after household agricultural production and considered this source more important than the local shop.

Villagers regarded the availability of food grains at the ration store as an advantage as it allowed them to avoid travelling to the market. They also evaluated the provision of food grains by the government as positive, as one villager put it: “There is no problem to get food, because of the rations.” However, some dissatisfaction with the programme existed.Footnote 21 Complaints included shortages of supply in certain stores and a lack of stores in very remote villages. Moreover, the misuse of the scheme due to the accreditation of several ration cards per household was reported. Families criticised the low quality of the food grains provided through the scheme as farmers tended to sell the better products outside government channels. In addition, Ladakhi farmers blamed the PDS as the cause for the unavailability of a market for locally produced staples in the district.

The preference for rice as opposed to “traditional food” was associated with various factors other than the economic. These included the new food preferences of the “younger generation” and their favouring “Indian” or “Western” lifestyles, the advantage of effortless preparation of rice as opposed to dishes based on homemade noodles. Similar to kholak (which remains uncooked), preparation time for rice is comparatively short and this is particularly appreciated during the summer months when agricultural work is intense. At the same time, people lamented the loss of “traditional” food which is considered to be more nutritious (“heavy”) and healthy.

Conclusion

The analysis of dietary patterns in Ladakh has illustrated changes in the food system over the past three decades. Besides an increase in dietary diversity, especially during the summer months, seasonality in the availability of food and access to food has been demonstrated. For vulnerable households, this seasonality leads to periodic food insecurity. Our evidence from Ladakh has shown how changing consumption patterns are connected to different dynamics. These encompass subsistence agriculture, the wider context of livelihood strategies and household assets, the advanced integration of the mountain region into a market economy and external actors with their initiatives.

The case of Ladakh illustrates the declining role of agricultural land-use as has been shown in studies from neighbouring mountain regions (e.g. Nüsser and Clemens 1996; Sinclair and Ham 2000; Kreutzmann 2006b). Today, the most important staples of the local diet are either produced by the households (barley, wheat) or purchased from ration stores (rice, wheat). Land-use strategies have changed towards an increase in vegetable cultivation. Different intervention programmes by the Agriculture Department and non-governmental organisations aim at higher production, e.g. through subsidies of seeds, greenhouse construction and new technologies. Surplus crops are sold for cash at local markets and contribute to on-farm income generation. Marketing activities are generally at a low level. Access to markets varies within the region as purchasing and vending options depend on infrastructure and market institutions as was also shown by Bürli et al. (2008) for the Moroccan Atlas.

Besides subsistence agriculture, monetary income is increasingly important for local household strategies. Diversification through off-farm employment is a strategy commonly employed in the rural South (Rigg 2006; Zimmerer 2007). Access to monetary income and the resultant possibility of purchasing foodstuffs enhance the diversification of dietary patterns. In the case of Ladakh, markets and shops in the district capital have become important sources of food and commodities. Rice, which cannot be produced locally, as well as wheat flour and sugar are bought from the market or from government “ration stores” at subsidised rates. Besides this economic incentive, changing preferences influence household decisions. Ladakhis consider rice to be a “modern” food and the ration store as an advantage for direct product availability in the village. As wheat has a higher risk of crop failure than barley, it is increasingly purchased while staple production is reduced to the cultivation of barley.

The state controls domestic staple prices through the PDS, thus aiming to reduce food insecurity in the country. Yet the efficiency of this program has been criticised and a combination of safety-net programs and increased income favoured for long-term food security (Ninno et al. 2007; Dorosh 2009). Moreover, the issues of “hidden hunger” and a strong seasonality of dietary patterns, which are characteristic for mountain environments, are not addressed by the PDS. The importance of the PDS for local households has created dependency on subsidised goods and is therefore contrary to programs aiming at self-sufficiency through increased agricultural production. Dependency on subsidies renders the population vulnerable should the national government decide on adjustment of the programme or major reforms.

The evidence from our case study in Ladakh has illustrated how food security is shaped by the interplay of local choices and external interventions. Individual households are embedded in webs of actors at the village level, but are also connected to government and non-government actors through the implementation of specific programmes (e.g. agricultural technology, food subsidies). Moreover, markets are shaped by the interaction of companies, traders and shopkeepers and thus influence choices at the village level.

The analysis suggests addressing the issue of malnutrition through tailor-made policies instead of narrow focuses on increased production or price support policies. It is considered critical to adapt policies and future development schemes to the regional specificities of mountain environments. As our evidence from Ladakh has shown, the implementation of targeted food subsidies does not respond to the important issue of micronutrient deficiencies. Instead, the challenge is to implement policies which take the different dimensions of the food system into account. Enhanced preservation and storage capacities, a growth in off-seasonal vegetable production, income opportunities and the advancement of education and nutritional knowledge should be priorities for supporting household strategies. Our studies show how the cropping of vegetables in home gardens has diversified local dietary patterns. Combined with information on health and nutrition and capacity-building on marketing skills, the promotion of vegetable cultivation can be more beneficial for mountain farmers (Jenny and Egal 2002; Bingen et al. 2003). State and national policies are in many cases not designed to take local demands, perceptions and aspirations into account. In the case of Ladakh, improved storage capacities to reduce the effects of seasonality are a field that has hitherto not been focused on. Another example is the formation of cooperatives and agreements on fixed market prices for cash crops which has been locally evaluated as a successful village-level strategy for rural income generation. The challenge remains to design policies which address food security at different scales and by the necessary breadth as well as to consider positive and negative effects of interventions (Maxwell and Slater 2003; Lang et al. 2009). It is therefore considered fruitful to focus studies on multiple levels and a number of drivers, which take the specific socio-economic and political developments of high mountain contexts into account (Fig. 1). This assessment of complex food systems can be the basis for food policies, which integrate environment, health and social relations and aim at sustainable food availability.

Notes

Until 1979, these two districts formed the conjoined district of Ladakh. Population of Leh district: 117,232. Population of Kargil district: 119,307 (Census of India 2001, accessed online, 27.08.2010: http://censusindia.gov.in/population_finder/Sub_Districts_Master.aspx?state_code=01&district_code=07)

Current infrastructure developments include the construction of a tunnel at Rohthang pass near Manali with the aim of creating an all-weather road access to Ladakh by 2015 (Times of India: IANS, June 28, 2010 “Rohtang Tunnel work launched”, accessed online, 21.07.2010: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/6101013.cms).

In adverse conditions this road is closed. Such conditions include heavy snowfall in winter as well as bridge destructions after flash floods. Since the most recent flash flood events, in August 2010, the village cannot be directly accessed by bus. The connection to Leh thus currently includes an additional three hours trek on foot.

In both locations the agricultural system was similar with identical ranges of plants that were single-cropped. Although villagers from Hemis Shukpachan have access to Leh for most of the time even during winter, this fact had no significant effect on dietary patterns as our interview data suggest. In the context of socio-economic change, the food and livelihood situation today varies much more between the different villages.

Meat consumption in Buddhist households increases during the winter and is considered ethically more correct than in times of vegetable abundance. Special food recommendations exist for elderly, pregnant and ill persons.

By the end of the winter, the cost of one kg of fresh vegetable (brinjal, cauliflower) is fivefold (100 IRP per kg) compared to the cost of the same vegetable during the summer (20 IRP per kg; Data from Leh 2009).

See Ripley (1995) on the social relevance of chang consumption.

The trade in Pashmina wool is an exception. See Ahmed (2004) for a detailed description of the Pashmina trade.

With the introduction of targeting, the government followed two objectives: Subsidies were to be for the benefit of the most vulnerable households and the overall costs of the programme were to be reduced. However, families above the poverty line continue to be granted access to food grains. The programme, de facto, still continues to work as a universal distribution system (Mooij 1999c).

This article focuses on staple foods. In addition, kerosene and sometimes edible oils are provided.

Procurement is especially from India’s “granaries” (Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh). See Economic Survey of India 2009–2010, p.199, accessed online, 31.08.2010:http://indiabudget.nic.in/es2009-10/esmain.htm.

The criteria vary between the states, given the difference in poverty line levels. Jammu & Kashmir poverty line was at 391.26 Indian Rupees per capita, per month in 2004/2005 (based on Mixed Recall Period, Reserve Bank of India 2009, p. 288).

BBC news online 18.12.2009, accessed online under: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/8419799.stm

In India, a fiscal year is from 1st April until 31st March of the following year.

The stabilization of prices within the country and an export ban on non-basmati rice has even contributed to the further increase of international prices (Dorosh 2009).

Shares of PDS staples of total consumption for statistical year 1999/2000: a) rice: 27.1% for rural population and 47% for urban population; b) wheat: 15.3% (rural) and 30.7% (urban).

PDS rations are granted to Tibetan refugees, but not to migrant labourers.

In individual cases, families reported having lost their ration cards, waited for a new ration card to be issued or lacked the assignment of a card e.g. due to uncompleted papers or lack of passport photographs.

Compare Mooij (1999c) for the implementation of the PDS in the states of Karnataka and Bihar.

References

Aggarwal, R. (2004). Beyond Lines of Control. Performance and Politics on the Disputed Borders of Ladakh, India. Durham: Duke University Press.

Ahmed, M. (2004). The Politics of Pashmina: The Changpas of Eastern Ladakh. Nomadic Peoples, 8(2), 89–106.

Ali, A. (2002). A Siachen Peace Park: The Solution to a Half-Century of International Conflict? Mountain Research and Development, 22(4), 316–319.

Archer, D. R., & Fowler, H. J. (2004). Spatial and Temporal Variations in Precipitation in the Upper Indus Basin, Global Teleconnections and Hydrological Implications. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 8(1), 47–61.

Attenborough, R., Attenborough, M., & Leeds, A. R. (1994). Nutrition in Stongde. In J. Crook & H. Osmaston (Eds.), Himalayan Buddhist Villages. Environment, Resources, Society and Religious Life in Zangskar, Ladakh (pp. 383–404). Bristol: University of Bristol.

Beek, M. van & Pirie, F. (Eds.). (2008). Modern Ladakh. Anthropological Perspectives on Continuity and Change (Vol. 20, Brill’s Tibetan Studies Library). Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Berzborn, S., & Schnegg, M. (2007). Vulnerability, Social Networks, and Resilience: Rural Livelihoods in the Richtersveld, South Africa. In B. Lohnert (Ed.), Social Networks: Potentials and Constraints (pp. 115–147). Saarbrücken: Verlag für Entwicklungspolitik.

Bingen, J., Serrano, A., & Howard, J. (2003). Linking Farmers to Markets: Different Approaches to Human Capital Development. Food Policy, 28(4), 405–419.

Bürli, M., Aw-Hassan, A., & Rachidi, Y. L. (2008). The Importance of Institutions in Mountain Regions for Accessing Markets: An Example from the Moroccan High Atlas. Mountain Research and Development, 28(4), 233–239.

Cannon, T. (2002). Food Security, Food Systems and Livelihoods: Competing Explanations of Hunger. Die Erde, 133(4), 345–362.

Cvejic, E., Ades, S., Flexer, W., & Gray-Donald, K. (1997). Breastfeeding Practices and Nutritional Status of Children at High Altitude in Ladakh. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 43, 376.

Dame, J., & Mankelow, J. S. (2010). Stongde Revisited: Land-Use Change in Central Zangskar. Erdkunde, 64(4), 355–370.

Dame, J., & Nüsser, M. (2008). Development Paths and Perspectives in Ladakh, India. Geographische Rundschau - International Edition, 4(4), 20–27. supplement.

Dev, S. M., Ravi, C., Viswanathan, B., Gulati, A., & Ramachander, S. (2004). Economic Liberalisation, Targeted Programmes and Household Food Security: A Case Study from India. IFPRI MTID Discussion Paper 68. Washington DC: IFPRI.

DFID (Department for International Development). (1999). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. London: DFID.

Dorosh, P. A. (2009). Price Stabilization, International Trade and National Cereal Stocks: World Price Shocks and Policy Response in South Asia. Food Security, 1, 137–149.

Dutta, A., & Kumar, J. (1997). Impact of Sex and Family Size on the Nutritional Status of Hill Children of Uttar Pradesh. The Indian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics, 31, 121–126.

Dutta, A., & Pant, K. (2003). The Nutritional Status of Indigenous People in the Garwhal Himalayas, India. Mountain Research and Development, 23(3), 278–283.

Ehlers, E., & Kreutzmann, H. (2000). High Mountain Ecology and Economy: Potential and Constraints. In E. Ehlers & H. Kreutzmann (Eds.), High Mountain Pastoralism in Northern Pakistan (Vol. 132, Erdkundliches Wissen) (pp. 9–36). Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag.

Ericksen, P. (2008). Conceptualizing Food Systems for Global Environmental Change Research. Global Environmental Change, 18, 234–245.

Faber, M., Schwabe, C., & Drimie, S. (2009). Dietary Diversity in Relation to Other Household Food Security Indicators. International Journal of Food Safety, Nutrition and Public Health, 2(1), 1–15.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations). (1996). Food: A Fundamental Human Right. Rome: FAO.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations) (2009a). More People than Ever Are Victims of Hunger. Online Press Release June 2009. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/newsroom/docs/pressreleasejune_en.pdf. Accessed 12 December 2009.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations). (2009b). The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Economic Crises - Impacts and Lessons Learned. Rome: FAO.

Finnis, E. (2007). The Political Ecology of Dietary Transitions: Changing Production and Consumption Patterns in the Kolli Hills, India. Agriculture and Human Values, 24, 343–353.

Gerster-Bentaya, M. (2009). Instruments for the Assessment and Analysis of the Food and Nutrition Security Situation at Micro and Meso Level. In K. Klennert (Ed.), Achieving Food and Nutrition Security. A Training Course Reader (3rd ed., pp. 111–136). Feldafing: InWent.

Goodall, S. K. (2004). Rural-to-urban Migration and Urbanization in Leh, Ladakh. Mountain Research and Development, 24(3), 220–227.

Government of India. Department of Food and Public Distribution. (2009). Annual Report 2008–2009. Department of Food and Public Distribution. Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. New Delhi: GoI.

Government of India. India Meteorological Department (GoI/IMD). (1967). Climatological Tables of Observatories in India (1931–1960). New Delhi: GoI.

Haan, L. J. de, & Zoomers, A. (2005). Exploring the Frontier of Livelihood Research. Development and Change, 36(1), 27–47.

Herbers, H. (1998). Arbeit und Ernährung in Yasin. Aspekte des Produktions-Reproduktions-Zusammenhangs in einem Hochgebirgstal Nordpakistans. (Vol. 123, Erdkundliches Wissen). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Hoddinott, J., & Yohannes, Y. (2002). Dietary Diversity as a Food Security Indicator. IFPRI. FCND Discussion Paper 136. http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/fcnbr136.pdf. Accessed 10 December 2010.

Imbruce, V. (2008). The Production Relations of Contract Farming in Honduras. GeoJournal, 73, 67–82.

Ingram, J., & Brklacich, M. (2002). Global Environmental Change and Food Systems - GECAFS: A New Interdisciplinary Research Project. Die Erde, 133, 427–435.

Ingram, J., Ericksen, P., & Liverman, D. (Eds.). (2010). Food Security and Global Environmental Change. London: Earthscan.

Jenny, A. L., & Egal, F. (2002). Household Food Security and Nutrition in Mountain Areas. An Often Forgotten Story. Rom: Nutrition Programmes Service, FAO-ESNP.

Kennedy, G., Nantel, G., & Shetty, P. (2003). The Scourge of "Hidden Hunger": Global Dimensions of Micronutrient Deficiencies. Food, Nutrition and Agriculture, 32, 8–16.

Kochar, A. (2005). Can Targeted Food Programs Improve Nutrition? An Empirical Analysis of India's Public Distribution System. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54, 203–235.

Kreutzmann, H. (2001). Development Indicators for Mountain Regions. Mountain Research and Development, 21(2), 132–139.

Kreutzmann, H. (2006a). People and Mountains: Perspectives on the Human Dimension of Mountain Development. Global Environmental Research, 10(1), 49–61.

Kreutzmann, H. (Ed.). (2006b). Karakoram in Transition. Culture, Development and Ecology in the Hunza Valley. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kreutzmann, H. (2008). Kashmir and the Northern Areas of Pakistan: Boundary-making along Contested Borders. Erdkunde, 62(3), 201–219.

Labbal, V. (2001). "Travail de la terre, travail de la pierre." Des modes de mise en valeur des milieux arides par les sociétés himalayennes. L’exemple du Ladakh. Unpublished PhD thesis, Université Aix-Marseille 1 - Université de Provence, Marseille.

Lamb, A. (1991). Kashmir. A Disputed Legacy 1846–1990. Hertingfordbury: Roxford Books.

Landy, F. (2009). Feeding India. The Spatial Parameters of Food Grain Policy. New Delhi: Manohar.

Lang, T., Barling, D., & Caraher, M. (2009). Food Policy. Integrating Health, Environment and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Little, P., & Watts, M. (Eds.). (1994). Living under Contract: Contract Farming and Agrarian Transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Madison.

Mankelow, J. S. (2003). The Implementation of the Watershed Development Programme in Zangskar, Ladakh: Irrigation Development, Politics and Society. (SOAS Occasional Paper 66). London: SOAS.

Maxwell, S., & Slater, R. (2003). Food Policy Old and New. Development Policy Review, 21(5–6), 531–553.

Messerli, B. (2004). Von Rio 1992 zum Jahr der Berge 2002 und wie weiter? Die Verantwortung der Wissenschaft und der Geographie. In W. Gamerith, P. Messerli, P. Meusburger, & H. Wanner (Eds.), Alpenwelt - Gebirgswelten. Inseln, Brücken, Grenzen. Tagungsbericht und Abhandlungen. 54. Deutscher Geographentag 2003. 28. September bis 4. Oktober 2003 (pp. 21–42). Heidelberg, Bern.

Mooij, J. (1999a). Food Policy and the Indian State. The Public Distribution System in South India. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Mooij, J. (1999b). Food Policy in India: The Importance of Electoral Politics in Policy Implementation. Journal of International Development, 11(4), 625–636.

Mooij, J. (1999c). Real Targeting: The Case of Food Distribution in India. Food Policy, 24(1), 49–69.

Namgail, T., Bhatnagar, Y. V., Mishra, C., & Bagchi, S. (2007). Pastoral Nomads of the Indian Changthang: Production System, Landuse and Socioeconomic Changes. Human Ecology, 35, 497–504.

Ninno, C. del, Dorosh, P. A., & Subbarao, K. (2007). Food Aid, Domestic Policy and Food Security. Contrasting Experiences from South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy, 32(4), 413–435.

Nüsser, M., & Clemens, J. (1996). Impacts on Mixed Mountain Agriculture in the Rupal Valley, Nanga Parbat, Northern Pakistan. Mountain Research and Development, 16(2), 117–133.

Osmaston, H. (1994). The Farming System. In J. Crook & H. Osmaston (Eds.), Himalayan Buddhist Villages. Environment, Resources, Society and Religious Life in Zangskar, Ladakh (pp. 139–198). Bristol: University of Bristol.

Pinstrup-Andersen, P. (2009). Food Security: Definition and Measurement. Food Security, 1(1), 5–7.

Porter, G., & Philipps-Howard, K. (1997). Comparing Contracts: An Evaluation of Contract Farming Schemes in Africa. World Development, 25(2), 227–238.

Rao, A., & Casimir, M. (Eds.). (2003). Nomadism in South Asia. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Reifenberg, G. (1998). Ladakhi Kitchen. Traditional and Modern Recipes from Ladakh. Leh: Melong Publications.

Reserve Bank of India. (2009). Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy. 2008–2009. Mumbai.

Rigg, J. (2006). Land, Farming, Livelihoods, and Poverty: Rethinking the Links in the Rural South. World Development, 34(1), 180–202.

Ripley, A. (1995). Food as Ritual. In H. Osmaston & P. Denwood (Eds.), Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5. Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth International Colloquia on Ladakh (pp. 139-198). New Delhi: Motilal Banardiss Publishers

Rizvi, J. (1999). Trans-Himalayan Caravans: Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods Perspectives and Rural Development. Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), 171–196.

Shetty, P. (2009). Incorporating Nutritional Considerations when Addressing Food Insecurity. Food Security, 1(4), 431–440.

Sinclair, J., & Ham, L. (2000). Household Adaptive Strategies: Shaping Livelihood Security in the Western Himalaya. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 21(1), 89–112.

Tröger, S. (2004). Handeln zur Ernährungssicherung im Zeichen gesellschaftlichen Umbruchs. Saarbrücken: Verlag für Entwicklungspolitik.

Wahlfeld, C. (2008). Auspicious Beginnings: A High Altitude Study of Antenatal Care Patterns and Birth Weight at Two Hospitals in the Leh District of Ladakh, India. Unpublished PhD thesis, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo.

Wiley, A. S. (2004). An Ecology of High-Altitude Infancy. A Biocultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, J. M., Campbell, m J, & Afzal, M. (1990). Heights and Weights of Children in Ladakh, North India. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 36, 271–272.

Zimmerer, K. (2007). Agriculture, Livelihoods, and Globalization: The Analysis of New Trajectories (and Avoidance of Just-So Stories) of Human-Environment Change and Conservation. Agriculture and Human Values, 24, 9–16.

Acknowledgements

The field survey was generously funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) in the context of the project “Food security in Ladakh: subsistence-oriented resource utilization and socio-economic change”. An earlier version of this paper has been presented and discussed at a workshop on “Food Security in High Mountains”, organized by the Mountain Research Initiative (MRI). The authors thank Markus Giger and Susanne Wymann von Dach for their comments on the manuscript. We thank the reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. We would like to express our gratitude to the people in Ladakh. We especially appreciate the help of Phuntsog Angmo (Hemis Shukpachan). Ravi Baghel (Heidelberg) has improved the English. We also thank Nils Harm (Heidelberg) for his contribution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dame, J., Nüsser, M. Food security in high mountain regions: agricultural production and the impact of food subsidies in Ladakh, Northern India. Food Sec. 3, 179–194 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-011-0127-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-011-0127-2