Abstract

This study explores what China’s central government has done in relation to education for sustainable development (ESD) and what Chinese higher education institutions (HEIs) have achieved in terms of ESD in response to SDG4. This is a qualitative case study focusing on China’s central government and Beijing Normal University (BNU). The main form of data analyzed was documents. In total, we collected 48 policy documents, six speech transcripts and work statements, and 167 news releases. The results show that ESD has not been implemented holistically in China. Educational sectors promoted ESD because sustainable development has been emphasized in the national political strategy. However, the specific meaning of sustainable development in the educational sector is unclear, and the implementation has not been systematic. Overall, more attention has been paid to the natural dimension of ESD than to the social dimension. At BNU, ESD activities are conducted through three mechanisms: a coercive mechanism, a professional mechanism, and a cultural mechanism. Health, culture, and environmental protection have received more attention than social equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the start of the new millennium, sustainable development has attracted considerable attention worldwide. Education serves as a significant tool to raise public awareness of sustainable development and to provide the knowledge and skills related to sustainable development. Consequently, people have gradually become aware of the importance of education for achieving sustainable development (McKeown et al., 2002; Orr, 1994). In 2015, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) adopted the Incheon Declaration for Education 2030 and set out “Towards inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning for all” as a new vision for the next 15 years, which was confirmed as the fourth sustainable development goal (SDG) for education (abbreviated as SDG4). SDG4 involves not only the distribution of educational resources but also the content of education for sustainable development (ESD). As emphasized in Target 4.7, all levels of education are expected to provide “the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development” (United Nations, 2015).

Although the idea of ESD has been widely disseminated, it will not be fully achieved until it is entirely embedded in local educational practices in all countries. In many countries, multiple measures have been adopted to promote and implement ESD, especially in higher education institutions (HEIs) (Abad-Segura & González-Zamar, 2021; Baughan, 2015; Fiselier et al., 2018; Sterling & Scott, 2008). As the biggest developing country, China has responded to ESD issues quickly and positively (C. Li, 2018). Description and analysis of how China conducts ESD in its HEIs can provide rich information on how ESD can be contextualized and coordinated with the indigenous social background in developing countries. However, the current attention paid to ESD practices in China is insufficient.

The immense capacity of the state in China, which is widely recognized (Edin, 2003), means that the greatest source of motivation and power for promoting ESD in China is the central government. Although there are numerous autonomous ESD activities led by HEIs, the influence of official policy is significant. Against this backdrop, in this study, we aim to answer two research questions: how has ESD been articulated by China’s central government and what have Chinese HEIs achieved in terms of ESD in response to SDG4? These two research questions are answered through analysis of China’s education policy and a case study of Beijing Normal University (BNU), which is engaged in ESD. This study provides a descriptive analysis of ESD policy in China and the ESD practice of Chinese HEIs and increases our understanding of the measures to promote ESD in China and the problems China faces.

Literature review

ESD and policies

Public policies support, guide, and sometimes constrain the implementation of ESD. Previous studies have criticized the hegemonic effect of the discourse on ESD and analyzed multiple discourses that articulated ESD in policy documents (Bengtsson, 2016; Blewitt, 2005; González-Gaudiano, 2016; Læss⊘e, 2010; Rauch & Steiner, 2006). For example, Blewitt (2005) analyzed a major national ESD initiative in the UK and found that there was tension between a managerial approach to protecting development and an ecological and synoptic methodology in keeping with the values of ESD.

Furthermore, many researchers have analyzed the content of ESD policies in various countries and the problems encountered during implementation (Bamber et al., 2016; Kuzich et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2013; Nomura & Abe, 2009; Summers et al., 2005; Tilbury, 2007). Examples include the comparative analyses of ESD policies in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland (Bamber et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2013), and an analysis of the supports and challenges shaping a school’s implementation of ESD in Australia (Kuzich et al., 2015).

Although previous studies have made numerous contributions to the literature, studies on ESD in China are scarce. Given that China’s national policy is noteworthy for its power, in this study, we attempt to address this gap.

ESD and higher education

Higher education has remarkable and direct influences on society. To date, ESD researchers have mainly focused on intra-university elements, such as the curriculum and instruction, campus operations, and activities aimed at achieving sustainability, and the perceptions and opinions of teachers and students regarding ESD.

Curriculum and instruction are important aspects of the transfer of knowledge and the cultivation of students’ understanding of ESD. Researchers have explored how universities in various countries integrate the notion of ESD into their curriculum and instruction (Argento et al., 2020; Fiselier et al., 2018; Paletta & Bonoli, 2019). For instance, Katayama et al. (2018) reviewed accumulated data on sustainable development-related teaching in all 193 HEIs in Turkey, and Lozano (2010) analyzed more than 5800 course descriptions from 19 schools at Cardiff University and called for a more balanced, synergistic, trans-disciplinary, and holistic perspective to promote the incorporation of sustainable development-related teaching into the curricula.

Campus operations and activities are crucial aspects of ESD practices that cultivate students’ emotive and practical understanding of sustainable development. Hayles (2019) explored the operation of an internship program on campus-based sustainability, and reported positive changes in students’ behavior regarding sustainability. The obstacles to implementing ESD holistically in universities were also identified and analyzed. For example, Nicolaides (2006) identified various obstacles to effective environmental management systems and ESD, including people’s fear of change, institutional inertia, and a lack of senior management consciousness with regard to what constitutes an environmentally friendly institution.

Furthermore, examining perceptions and ideas regarding ESD in HEIs can help us understand the effects of ESD practices and identify problems. Cotton et al. (2007) investigated lecturers’ views on sustainable development and concluded that while many lecturers found the language of ESD inaccessible, they expressed a high level of support for sustainable development. Students’ and teachers’ self-perceived level of sustainability awareness was also investigated (Cho, 2019; Saqib et al., 2020; Savelyeva & Douglas, 2017).

Overall, previous studies have mainly focused on Western countries, with most attention paid to the curriculum and instruction practices (Barth & Rieckmann, 2016; Weiss & Barth, 2019). By contrast, in this study, we analyze the case of China from the macro policy perspective.

ESD and China

As the biggest developing country in the world, China has made substantial progress in terms of sustainable development. However, compared with the outcomes in other countries, ESD in China has not attracted adequate attention from scholars, especially ESD in China’s universities and the macro policy environment in which the universities are situated.

In previous studies, some scholars have focused on pre-school education, basic education, and adult education (Chan et al., 2009; Luo et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2010). Zhou (2021) verified that the kindergarten curriculum in China incorporated the environmental dimension of ESD, but ignored its social and economic dimensions. Regarding basic education, Zhang (2010) identified various ways in which China’s schools actively shifted from environmental education to education for sustainable development during the period 1998–2009. Yao (2018, 2019), who examined adult education, emphasized that a blended learning environment combining online learning and in-person learning could facilitate ESD.

Scholars who have examined higher education in China have mainly focused on intra-university factors such as the curriculum and campus operations, while downplaying the role of the macro policy background (Qian et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). Yuan and Zuo (2013) surveyed students from Shandong University in an effort to identify the factors that students believed to be either important or unimportant in relation to ESD. Tan et al. (2014) summarized the transformation from an energy- and resource-efficient campus to a green campus in China, including how it was accomplished and deficiencies in the process. Some scholars who conducted international comparisons argued that ESD in China required pedagogical change (Lu & Zhang, 2013), was shaped by political ideology and traditional social values (Asif et al., 2020), and needed to combine international and endemic knowledge (Kovaleva et al., 2019).

Defining ESD and theoretical framework

Since 1992, the term ESD has been enriched and developed constantly. ESD “empowers learners to make informed decisions and responsible actions for environmental integrity, economic viability and a just society for present and future generations, while respecting cultural diversity” (UNESCO, 2014). While there are multiple interpretations of ESD over the years (Ferreira, 2009; Hopkins & McKeown, 2003; Scott, 2015; Stables & Scott, 2002), the need for ESD to address specific knowledge, skills and values is pertinent (Alexander et al., 2018). Therefore, this study defines ESD as the educative activities that are explicitly designed to improve its participants' awareness of sustainable development. It helps all learners acquire the knowledge, skills, perspectives, and values required by citizens to lead productive lives, make informed decisions and assume active roles locally and globally in facing and resolving global challenges (UNESCO, 2015), and its themes include “human rights, gender equality, health, comprehensive sexuality education, climate change, sustainable livelihoods, and responsible and engaged citizenship, based on national experiences and capabilities” (UNESCO, 2015, p. 19).

In terms of means to promote ESD in HEIs, previous research highlights three main types of practice: formal curriculum (Ceulemans & Severijns, 2019; Fiselier et al., 2018; Katayama et al., 2018), informal curriculum (Hayles, 2019; Savelyeva & Douglas, 2017), and campus curriculum (Mcmillin & Dyball, 2009; Nicolaides, 2006). The formal curriculum involves courses and academic programs, the informal curriculum involves various activities that influence the wider student experience, and the campus curriculum involves learning opportunities arising from the university campus itself (Hopkinson et al., 2008). The production and implementation of the curriculum take place within the educational policy context (Ball, 2012, p. 133). Public policy includes not only the official enactments of government, usually in the form of rules, regulations, laws, ordinances, and administrative decisions, but also informal practices (Fowler, 2000, p. 5). Besides, it involves “the inactions of the government, not simply what the government does” (Cibulka, 1994). In China, though the local participation of universities in curriculum development is allowed, the central government still formulates the broad framework and overall plans for education through public policy, including regulations on the curriculum (Qi, 2011, p. 29). Therefore, the national policy context influences the way HEIs implement ESD and the content of the ESD curriculum (Franco et al., 2019; Nomura & Abe, 2009; UNESCO, 2020).

Consequently, in addition to the formal, informal, and campus curriculum provided by HEIs for ESD, this study also pays attention to ESD policies, which are defined as systems of official guidelines, informal practices and inactions to direct, facilitate, and regulate the practice of ESD. Accordingly, we construct the theoretical framework to guide the data collection and analysis of this study (see Fig. 1).

Research method

We undertook a qualitative case study focusing on the Chinese central government and BNU, which is a comprehensive, research-intensive university focusing on basic disciplines in sciences and humanities. The 2020 QS World University Rankings ranked BNU 277th among world universities and 10th among Chinese mainland universities. As the first university in China to award master’s and doctoral degrees in education, BNU has played an important role in improving the quality of educational innovation in China, preparing professional teachers and future educators, and housing the think tank underlying China’s education system. BNU has served as a leader in the educational field, and the educational practices here have usually been imitated by other normal universities in China. Not merely has BNU acted as an advocate that implements public educational policy actively, but also as an entrepreneur that promotes educational policy change. Therefore, the implementation of ESD policy and ESD practices learned from BNU could be informative.

The main form of data analyzed are documents. Three types of documents were collected: policy documents published by UNESCO, the China State Council (CSC), the China Ministry of Education (CMOE), and BNU; public speeches and work statements; and news releases issued by the CSC, the CMOE, and BNU. First, we looked through all the policy documents, public speeches, and news releases on the website of CMOE since 1998 and all the news releases, public announcements, and class schedules on the website of BNU since 2004. Then, we selected those documents that referred to the term “ESD (Ke chixu fazhan jiaoyu)” and those documents that involved any themes of ESD mentioned above even if they did not use the term ESD directly. What is more, if other policies were mentioned in the documents above, we also searched for the original documents and added them to the list. In total, 48 policy documents, six speech transcripts and work statements, 167 news releases and public announcements, and 172 class schedules were collected.

All of the documents were carefully read and then coded using MAXQDA 2020. The documents are categorized by the organizations that publish them, and we classified them into three types: international, national, and university documents. For each type of document, the first step was open coding (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). Each document was read and coded separately to identify original ESD themes. Then, axial coding was conducted by considering the connections among the original themes. Finally, all of the codes were integrated and reconsidered to generate an explanatory framework.

Research results

Through the analysis of the policy documents, we find that the ideal of sustainable development in China is driven by national policy. As a way to achieve the national strategy of sustainable development, ESD in China’s educational policy is symbolized and fragmented, and the connotations of ESD are environmental-centered. According to the data from the case of BNU, the implementation of ESD is mechanism-guaranteed in HEIs.

National-policy-driven sustainable development in China

Sustainable development has become an ideal that is taken for granted by China’s policy-makers. For example, the Declaration for Building a Sustainable Development Campus stated that “achieving comprehensive, coordinated and sustainable development has become the broad consensus of the whole society” (CMOE, 2008a).

Sustainable development is not only generally mentioned in policy texts as an ideal, but is also integrated into the national strategy guiding China’s development. Sustainable development was first included in China’s national development strategy in 1994 when the central government published China’s Agenda 21: White Paper on China’s Population, Environment, and Development, which marked the adoption of sustainable development as a national strategy. Soon after, in the Outline of the Ninth 5 Year Plan (1996–2000) for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-range Objectives to the Year 2010, sustainable development was cited as one of the nine major principles guiding the national economy and social development (P. Li, 1996). Since then, the importance of sustainable development has been emphasized in each new 5 Year Plan.

Although since 1994 every Chinese president has recognized the significance of sustainable development, they have adopted different interpretations of the term. Therefore, the political discourse in relation to contextualizing sustainable development within China’s national strategy has changed over time (see Table 1).

During the three periods shown in Table 1, the relationship between economic development and sustainable development has gradually shifted from the affiliation of the latter with the former to their dialectical unification to reflect these different interpretations. However, resources and the environment have always been the core issues in relation to sustainable development. Meanwhile, social justice is rarely considered in relation to sustainable development under China’s national strategy.

Symbolized and fragmented ESD in China’s educational policy

In 1995, the third president of China, Jiang Zemin, decided to implement the Strategy for Invigorating China Through Science and Education (Kejiao Xingguo Zhanlve) as a national strategy, underlining “the importance of education and science and technology in promoting economic and social development” (Strategy for Invigorating China, 2019). Since then, the implementation of education policy has been regarded as a means toward the end of achieving China’s national development goals. Therefore, the philosophy of education pertains to the political philosophy of the nation. In most of the major education policies, a statement is included at the beginning of the text outlining the conformity between the policy and the national development strategy by way of providing the rationale for the policy.

This paradigm also exists in the field of ESD. Because of the affiliated role of education in serving the development of the economy and society, ESD is also treated as a way to achieve China’s SDGs. As an important national strategy, sustainable development is often mentioned in ESD policies to demonstrate that the education system has fulfilled its obligation to facilitate China’s sustainable development. As the interpretation of sustainable development changes, the method of mentioning sustainable development in ESD policies alters accordingly. Table 2 shows the different interpretations of sustainable development in ESD policies at different stages.

It can be seen from Table 2 that the interpretations of sustainable development in ESD policies are different in response to changes in the interpretations of sustainable development in China’s national strategy. Before 2003, the declared national strategy on sustainable development in relation to ESD policy was the Sustainable Development Strategy (SDS), which was implemented from 1993 to 2003; from 2005 to 2010, the declared national strategy on sustainable development in relation to ESD policy was the Scientific Outlook on Development (SOD), which was implemented from 2003 to 2013; and from 2014 to 2020, the declared national strategy on sustainable development in relation to ESD policy was the Construction of Ecological Civilization (CEC), which was implemented in 2013 and has continued to the present day. Furthermore, the UN Agenda and SDGs are rarely quoted in China’s ESD policy (they are mentioned in only three out of 17 policy documents), indicating the translation of sustainable development from a global discourse to a local one in terms of China’s ESD policy.

However, the frequent mention of sustainable development has not led to a comprehensive explanation of what it means within the education sector. Sustainable development is generally only used as a label by China’s central government in most education policies, and the education department has followed a global, even symbolic, ideal of sustainable development presented by the central government without a concrete conceptualization of what ESD involves.

Consequently, without a concrete understanding of ESD, the implementation of ESD is often fragmented and desultory. Apart from the Guidelines for the Implementation of Environmental Education in Primary and Secondary Schools, which have not been revised since they were published in 2003, we were unable to find any national guidelines on ESD. However, this does not mean that there has been no attention paid to ESD. From 2014, the term “Ecological Civilization Education (ECE)” began to appear frequently in education policies, seemingly reflecting the emphasis placed on ESD. From 2014 to 2017, ECE was required to be incorporated into moral education and Chinese traditional culture education, and in 2019, the only specific policy on ESD, the Notice on Implementing Xi Jinping’s Ecological Civilization Thought in Primary and Secondary Schools and Enhancing Ecological Environmental Awareness, was published. Nonetheless, this trend seems to be more political than professional under the guise of implementing Xi Jinping’s thoughts on ecological civilization. ESD has not yet been presented as a separate educational module in China, and it is unlikely that ESD will be implemented continually and systematically at the different levels of education.

Environmental-centered ESD in China

As mentioned above, there has been neither a specific interpretation nor a holistic implementation of ESD in relation to China’s education policy. Nonetheless, it is still possible to infer the connotations of ESD in China by analyzing two types of information: the use of the term “sustainable development” and synonymous terms in policy texts, and the learning content of ESD, that is, what knowledge and ideas are emphasized in ESD. The results suggest that the critical issues in relation to ESD include environmental awareness, environmental action, and benevolence.

Environmental awareness

Environmental awareness is the fundamental aspect of China’s ESD. In almost all policy documents regarding ESD, the protection of the environment is seen as a prerequisite for achieving sustainable development. First, environmental degradation is regarded as one of the greatest obstacles to sustainable development. Second, environmental protection education is an indispensable part of ESD. Almost every policy involving ESD includes environmental awareness or environmental protection in the learning content. Interestingly, protecting the environment is not only a subordinate aspect of sustainable development, but sometimes also used as a synonym for implementing sustainable development. For example, the Notice on the Issuance of the Guidelines for the Implementation of Environmental Education in Primary and Secondary Schools states: “…It is the consensus of the world today to protect the environment and implement sustainable development strategies” (CMOE, 2003).

In this excerpt, both environmental protection and sustainable development are emphasized. This is not an isolated instance. In a speech at the 2008 “Sustainable Development Campus Seminar,” Vice Minister of Education Wu Qidi stated: “College students are the future of the country…their environmental awareness and sustainable development awareness will directly affect the effectiveness of our country’s sustainable development in the future” (CMOE, 2008b).

Mentioning environmental awareness alongside sustainable development awareness implies the ambiguous relationship between environmental protection and sustainable development in China’s ESD policy, which leads to a logical conundrum. On the one hand, this ambiguity reflects the lack of attention paid to ESD, as mentioned earlier, but on the other hand, it once again highlights the importance of environmental protection in the eyes of policy-makers when implementing sustainable development.

Environmental action

Environmental awareness can be achieved mainly through teaching students how to protect the environment. Therefore, environmental action is also an important issue. The environmental actions that are emphasized in China’s ESD policy include developing new technologies and living a sustainable lifestyle.

The level of emphasis on technologies differs at the various levels of education. Prior to university, the key point is to help students understand the technological advancement as a double-blade sword: the development of new technologies improves people’s lives but also damages the environment. In higher education, the focus changes from the evaluation of technologies to the process of developing new technologies. Higher education institutions are asked to “strengthen the research and application of energy-saving and environmental protection technologies” and “conduct scientific research and develop technologies under the principle of sustainable development” (CMOE, 2008a).

Another aspect of environmental action involves teaching students to adopt a sustainable lifestyle, through actions such as saving water, electricity, food, and other resources, sorting their garbage, and minimizing consumption. Of these actions, frugality has been emphasized to a greater or lesser degree over the years, with policy amendments relating to this issue published in 2005, 2008, 2011, 2013, and 2020. This is possible because diligence and thrift have always been regarded as traditional virtues of the Chinese people.

Benevolence

Environmental and ecological issues are of primary importance in China’s ESD policy. By contrast, social issues are rarely mentioned. In the Guidelines for the Education of Excellent Traditional Chinese Culture published in 2014, it was stated that educators should (CMOE, 2014, para. 18):

“Carry out social care education focusing on benevolence and selflessness. Guide young students to correctly handle the relationship between individuals and others, individuals and society, and individuals and nature, learn to be kind, understand others, respect the elderly, love the young, support the disabled, care for the society, respect nature, and cultivate the spirit of collectivism and awareness of ecological civilization.”

The term “ecological civilization” has underpinned the localization of sustainable development by China’s central government since 2013. Here, the natural and social dimensions of sustainable development are intertwined and recontextualized into Chinese traditional culture. As one of China’s traditional spirits, benevolence is the ideal way for many Chinese people to deal with interpersonal relationships. Therefore, the juxtaposition of “individuals and others,” “individuals and society,” and “individuals and nature,” and the co-occurrence of “respect nature” and other social behaviors such as “learn to be kind,” “understand others,” and “care for the society” reflect the dual nature of sustainable development in China. On the one hand, it involves a harmonious relationship between people and nature, while on the other hand, it involves harmonious relationships among people, which is closely related to benevolence in Chinese traditional culture. However, this duality has not been systematically and logically integrated into China’s current ESD policy.

In summary, the social dimension of sustainable development, which calls for social solidarity and social justice, such as cultural diversity, global citizenship, human rights, and gender equality, has gone unheeded in China’s ESD policy, with relevant issues only being mentioned sporadically in current policy documents. Meanwhile, the natural dimension of sustainable development, which involves environmental protection and low-carbon lifestyle, is always in the spotlight. In contrast to China’s approach, UNESCO’s policy document treats ESD as including a group of concepts related to not only a sustainable lifestyle and the protection of the environment, but also social justice including human rights, gender equality, cultural diversity, and global citizenship (UNESCO, 2014, 2015). This implies the interdependence of economic, social, and environmental development processes. Compared with the UNESCO statement, China’s ESD policy rarely mentions issues such as human rights and gender equality.

Mechanism-guaranteed ESD implementation: the case of BNU

BNU is committed to promoting ESD in multiple ways. In 2008, BNU joined the Declaration of Building Sustainable Development Campus along with 31 other universities and promised to “integrate the concept of sustainable development into the whole process of talent cultivation.” In 2012, BNU joined the Partnership for SDGs online platform organized by the UN and conducted a sustainability project to encourage research on and teaching of sustainable development at BNU from 2012 to 2015. In general, BNU implements ESD through three mechanisms: coercive mechanism, professional mechanism, and cultural mechanism, corresponding to three types of ESD activities: political activities, teaching activities, and club activities.

Coercive mechanism

Because of the integration of sustainable development into China’s national strategy, sustainable development is treated as a political idea that should be inculcated to each college student. Thus, ESD plays an important role to fulfil the political task and spread political beliefs. In this way, ESD is implemented through regulation and students must participate in obligatory ESD activities to avoid punishment. These political activities in relation to sustainable development embody a coercive mechanism aimed at promoting ESD. Complying with policies from the central government, BNU conducts two types of political activities in relation to ESD: ideological and political education, and Party branch activities.

Ideological and political education. In China, each college student must participate in ideological and political education. The Theoretical System of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics (TSSCC) is an important element of the content of ideological and political education.Footnote 1 As noted earlier, the notion of sustainable development has been contextualized in terms of China’s national strategy and has been translated into various political discourses during different periods. Table 1 shows that the ideal of sustainable development has been promoted in the form of SDS, SOD, and CEC at various times. Because of its high level of embeddedness in both the national strategy and Party theory, sustainable development is automatically included in the ideological and political education curriculum. At BNU, students must attend one lecture and participate in two activities during their sophomore year. From September 2018 to January 2021, BNU conducted 34 lectures and 34 practical activities. Of these, eight lectures and 13 practical activities were related to ESD and included five themes: cultural diversity, the environment, global citizenship, health, and social equity.

Party branch activities. As the sole ruling party in China, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has more than 90 million members, including more than 1.9 million college students, and more than 4.5 million basic Party organizations (2019 Statistical Bulletin, 2020). Each university is required to set up student Party branches to educate, manage, and supervise student CPC members. Each student CPC member must participate in at least 32 h of learning activities organized by the Party branch each academic year.

At BNU, student CPC members are required to learn the TSSCC, including SOD and CEC.Footnote 2 There are two main forms of learning activities: theoretical learning and practical learning. Each student Party branch is required to organize theoretical learning activities at least once every three months. The topics of the theoretical learning change over time in response to changes in national strategy and Party theory. Student Party branches are encouraged to conduct practical learning activities, including volunteering, visits, investigations, and competitions. For example, a student Party branch organized a practical activity called “Living a Green Life,” which involved a visit to the 2019 International Horticultural Exhibition in Beijing. The university provides a certain amount of funding to each Party branch to support its practical activities.

Since college students are required to study national strategy and Party theory, in both of which the notion of sustainable development is embedded, learning about sustainability is compulsory, and is achieved through political activities. This is a notable way of implementing ESD in China. Nonetheless, sustainable development is merely an optional theme in political activities at BNU, and may not be emphasized given the wide range of political issues to be addressed.

Professional mechanism

When conducting ESD through the professional mechanism, BNU treats sustainable development as relevant knowledge that can be communicated to students on the basis of academic autonomy. At BNU, there are multifarious academic activities focused on ESD, such as the curriculum, lectures, study-abroad programs, professional practice, and academic forums. For the various types of academic activities, the arrangement of curriculum for undergraduates is the best manifestation of the efforts made at the university level to support ESD. We analyzed courses on sustainability for undergraduates during the academic year from September 2020 to June 2021.Footnote 3

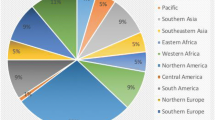

Although BNU does not provide any specific ESD module, there are 172 courses offered to students that include themes related to sustainability. After coding, we divided these courses into 6 categories according to their content: comprehensive sexuality education (e.g. Human Sexuality), cultural diversity (e.g. Comparison of Chinese and Foreign Cultures), environment/ecology/resources (e.g. Natural Resource Conservation), global citizenship (e.g. Global Climate Change and Responsibility of College Students), health (e.g. Developmental Biology and Human Health), and social equity (e.g. Educational Equity and Public Policy) (see Table 3). In terms of the number of courses offered, environment/ecology/resources, health, and cultural diversity are the three most prominent themes, with much less attention paid to comprehensive sexuality education, global citizenship, and social equity.

At BNU, undergraduates are required to take courses from the general courses module and the professional courses module. The content of the former corresponds to the general knowledge and attitude on sustainability, which is arranged by the university, and the content of the latter corresponds to the professional knowledge and values on sustainability, which is arranged at the discretion of different departments.

The general courses module includes six sub-modules: Nationalism and Values (NV), International Vision and Multiple Civilizations (IVMC), Classics Study and Cultural Inheritance (CSCI), Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM), Art and Aesthetics (AA), and Social Development and Civic Responsibility (SDCR). Table 4 shows the number of ESD courses on different themes in these six sub-modules.

It can be seen from Table 4 that SDCR covers all six themes, indicating that civic responsibility is seen as a multidimensional concept at BNU. Meanwhile, how to keep healthy is seen as important general knowledge to achieve sustainability. However, neither specific curriculum module, nor teaching programs on ESD have been conducted by the university, which means that teachers have not received any support from the university to promote ESD in teaching.

In terms of the professional knowledge of ESD, only five themes are involved. As shown in Table 5, knowledge of the natural dimension of sustainable development receives more attention than the social dimension, which continues the disproportion in the national ESD policy. In addition, most ESD courses are offered as elective courses, and only 13 of the 22 departments (59%) offer professional courses on ESD. Thus, more attention should be paid to ESD by more departments in the professional course module in the future.

Cultural mechanism

Club activities in relation to sustainable development embody the cultural mechanism aimed at promoting ESD, in which sustainable development is treated as a cultural ideal about what the world should be and what kind of life people should live. The establishment of clubs focused on the subject of sustainable development and the organization of club activities involving sustainable development reveal the voluntary acceptance and local practice of sustainability by club members. Club activities at BNU are mainly focused on sustainable lifestyles and involve two themes: environmentally friendly lifestyles and healthy lifestyles.

Environmentally friendly lifestyles. Several clubs aim to promote environmentally friendly lifestyles through long-term programs and a range of ad hoc activities.

The White Dove Green Environmental Protection Center (WDGEPC) is a department of the White Dove Youth Volunteer Association, the biggest student volunteer agency at BNU. The WDGEPC manages seven long-term programs aimed at promoting knowledge regarding environmental protection and initiating action in relation to environmental protection (see Table 6).

Some small clubs also organize activities to promote environmentally friendly lifestyles from time to time. These activities are more interesting, with the aim of attracting participants, for instance, debating competitions and quiz contests on the theme of environmental protection.

Healthy lifestyles. More than 10 clubs have been established at BNU to promote physical health and mental health. The two most representative activities organized each year are the “Sunshine Sports Training Camp (SSTC)” and “Mental Health Day (MHD).”

The SSTC is run by the BNU Student Union Association each year and lasts for an entire semester. The SSTC consists of five sub-camps corresponding to five common sports in China: Strength Training Camp, Yoga Camp, Table Tennis Camp, Basketball Camp, and Aerobics Camp. Students can join a camp and spend 60–120 min on training each week. To encourage and help students to live healthy lives, professional coaches are invited to direct the training of participants.

The MHD was originally established by BNU in 2000, and was then formally designated National Student Mental Health Day by the CMOE in 2004. A series of activities such as psychodrama, lectures, and a psychological public service competition are held every April and May by more than 10 faculties and departments to guide students in paying attention to their mental health.

In summary, the implementation of political activities, academic activities, and club activities represents a combination of coercive, professional, and cultural approaches to promoting ESD at BNU, in which sustainable development is treated as a political idea, general and professional knowledge, and cultural ideal. However, the university has not made a comprehensive effort to promote ESD. Furthermore, attention is unevenly divided among various sustainable development themes, with greater emphasis on environmental protection, health, cultural diversity, and sustainable lifestyles than on social justice, gender equality, and global citizenship. Consequently, ESD is still not treated holistically at BNU.

Conclusion and Discussion

In this study, we examined what China’s central government has done in relation to ESD and how the Chinese HEIs have implemented ESD. Our analysis revealed that ESD has not been implemented holistically in China. Educational sectors emphasized ESD because sustainable development is a part of the national political strategy. However, in the educational sector, the specific meaning of sustainable development is not articulated in an integrated framework, and the implementation is not designed systematically. Overall, more attention is paid to the natural dimension of ESD than to the social dimension. At BNU, ESD activities are conducted through three mechanisms: a coercive mechanism, a professional mechanism, and a cultural mechanism. Health, culture, and environmental protection have received more attention than social equity.

In line with existent studies that found ESD policy as a global discourse was recontextualized when it was adopted in different regions (Martin et al. 2013), we also identified a discrepancy between China’s and UN’s ESD policies: whereas the latter is more comprehensive, the former has an intensive focus on the natural dimension and inattention of the social dimension of sustainable development. Our finding resonates with Zhou’s (2021) conclusion that such imbalance existed in curriculum, and indicates the possible link between unbalanced curriculum and unbalanced policies, which is not well explored by previous studies.

Another problem that scholars already found was the lack of specific instruction guidance and incentive mechanism in policy (Kuzich et al., 2015). Similarly, we only found one document in 2003 that specified the content and method of teaching for environmental protection, without articulating the values of ESD or encouraging teachers to prioritize ESD in their agendas. Moreover, in China’s educational policies ESD is marginalized and does not constitute an independent theme, and the core values of ESD are, at best, ambiguously articulated in policy documents.

At the university level, scholars have long noticed the institutional inertia for ESD policy change (Nicolaides, 2006), the over-specialization of the ESD curriculum (Lozano, 2010) and the lack of a good top-level design for university ESD policies (Tan et al., 2014). Our analysis on university policy documents showed that these problems were likely interconnected in Chinese context. Without university-level coordination, each department just conducted ESD within their disciplinary boundaries, without enough incentives to experiment on interdisciplinary collaboration, which corroborates Lozano and other researchers’ (2015) finding that HEIs has been “compartmentalized and not holistically integrated throughout the institutions.”

Previous studies also found the influence of political ideology on ESD in China, with a special emphasis on teacher’s classroom instruction (Asif et al., 2020). By contrast, our research highlights not only the effect of political factors on teaching and learning sustainable development, but also the capacity of political institutions, such as the student Party branch of the Communist Party of China, to mobilize students to engage in ESD, which is a “hidden curriculum” that previous studies usually ignore.

In addition, scholars like Lu and Zhang (2013) advocated for applying bottom-up approach to transform ESD in Chinese universities. According to the result of our research, the variety of activities that student clubs organized and the irreplaceable role they played for promoting ESD have already demonstrated that such bottom-up approach did exist and make a difference in China.

In general, we found that the attention that the government paid to ESD was insufficient. In education policies, sustainable development was not prioritized. Besides, the university mainly passively implemented government policies without the initiative of institutional change. The deficiency of institutional and financial support largely explains why the university lacks incentive for such change. Based on these findings, this study suggests that multi-agent participation should be encouraged in China to promote ESD. At the national level, policymakers should attach more importance to ESD and establish a supportive institutional environment. There should be stronger mobilization from the government to inspire institutionalized practice on ESD, e.g. special funds should be established to motivate ESD degree programs. A holistic conceptualization of ESD is also needed in educational policy, which calls for equal emphasis on both the natural dimension and the social dimension of sustainability in ESD practice. At the university level, more frequent communication between different departments should be encouraged to achieve a general consensus on how to promote ESD in the cultivation of students and the ESD curricular integration from the university is essential. Furthermore, more resources should be provided to enable teachers and students to explore multiple forms of ESD practice from the bottom up.

In this study, we explored the meaning of ESD as seen by the central government of China and the mechanisms through which ESD is implemented in Chinese HEIs. Theoretically, this helps us to understand how ESD is transformed from a global notion into local political discourse. Practically, it can assist the decision-making process and lead to improvements in China’s ESD practices. Future research opportunities exist to compare the interpretation of ESD from different countries, especially the multiple ways in which different countries internalize ESD in national policy. What is more, future research can also be undertaken to explore the relationship between national policy and ESD practice in HEIs from the perspective of stakeholders in universities, e.g. how do administrators, teachers, and students understand national ESD policy and how does their understanding influence their ESD practice. Finally, more studies should be conducted to access the effects of ESD practice and programs in HEIs.

Data availability

Policy documents, public speeches, work statements, and news releases are obtained from the website of the China State Council (https://www.gov.cn/), the China Ministry of Education (http://www.moe.gov.cn/), and Beijing Normal University (https://www.bnu.edu.cn/).

Notes

In China, almost every generation of the leading collective of the CPC develops their own theory (collectively labeled as the Theoretical System of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics) to guide Party members and determine the direction of China’s development. After 1978, the second-generation leading collective developed Deng Xiaoping Theory; after 1989, the third-generation leading collective developed the Theory of Three Representations; after 2002, the fourth-generation leading collective developed the Scientific Outlook on Development; after 2012, the fifth-generation leading collective developed Xi Jinping’s Thoughts on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. The national strategies in each period come from the Theoretical System of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics decided by each generation of the leading collective of the CPC.

The documents and news releases we found on the BNU website were dated from 2008 to 2020. Since there were no documents prior to 2003, there is no information about SDS.

In China’s universities, the first semester generally runs from September until January of the following year, and the second semester runs from February until June.

References

2019 Statistical Bulletin of the Communist Party of China. XINHUANET. Retrieved June 30, 2020, from http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-06/30/c_1126178928.htm

Abad-Segura, E., & González-Zamar, M.-D. (2021). Sustainable economic development in higher education institutions: A global analysis within the SDGs framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 294, 126133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126133

Alexander, L., Julia, H., & Byun, W. J. (2018). Issues and trends in Education for Sustainable Development. UNESCO Publishing.

Argento, D., Einarson, D., Mårtensson, L., Persson, C., Wendin, K., & Westergren, A. (2020). Integrating sustainability in higher education: A Swedish case. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21(6), 1131–1150. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-10-2019-0292

Asif, T., Guangming, O., Haider, M. A., Colomer, J., Kayani, S., & Amin, N. (2020). Moral education for sustainable development: Comparison of university teachers’ perceptions in China and Pakistan. Sustainability, 12(7), 3014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12073014

Ball, S. J. (2012). Politics and policy making in education: Explorations in sociology. Routledge.

Bamber, P., Bullivant, A., Glover, A., King, B., & McCann, G. (2016). A comparative review of policy and practice for education for sustainable development/education for global citizenship (ESD/GC) in teacher education across the four nations of the UK. Management in Education, 30(3), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020616653179

Barth, M., & Rieckmann, M. (2016). State of the art in research on higher education for sustainable development. Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development (pp. 100–113).

Baughan, P. (2015). Sustainability policy and sustainability in higher education curricula: The educational developer perspective. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(4), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1070351

Bengtsson, S. L. (2016). Hegemony and the politics of policy making for education for sustainable development: A case study of Vietnam. The Journal of Environmental Education, 47(2), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2015.1021291

Blewitt, J. (2005). Education for sustainable development, governmentality and learning to last. Environmental Education Research, 11(2), 173–185.

Ceulemans, G., & Severijns, N. (2019). Challenges and benefits of student sustainability research projects in view of education for sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(3), 482–499. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2019-0051

Chan, B., Choy, G., & Lee, A. (2009). Harmony as the basis for education for sustainable development: A case example of Yew Chung International Schools. International Journal of Early Childhood, 41(2), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03168877

Cho, M. (2019). Campus sustainability: An integrated model of college students’ recycling behavior on campus. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(6), 1042–1060. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-06-2018-0107

Cibulka, J. G. (1994). Policy analysis and the study of the politics of education. Journal of Education Policy, 9(5), 105–125.

CMOE. (2003). Zhongxiaoxue huanjing jiaoyu shishi zhinan (shixing) [Notice on the issuance of the guidelines for the implementation of environmental education in primary and secondary schools]. Retrieved November 25, 2020 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s7053/200310/t20031013_181773.html

CMOE. (2008a). Jianshe ke chixu fazhan xiaoyuan xuanyan [Declaration for building sustainable development campus]. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A14/A14_other/2008a04/t2008a0403_75828.html

CMOE. (2008b). Zai jianshe ke chixu fazhan xiaoyuan yantaohui shang de jianghua [A speech at the Sustainable Development Campus Seminar]. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A14/A14_other/2008b04/t2008b0403_75827.html

CMOE. (2014). Wanshan zhonghua chuantong youxiu wenhua jiaoyu zhidao gangyao [Guidelines for the education of excellent traditional Chinese culture]. Retrieved November 26, 2020, from http://old.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s7061/201404/166543.html.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21.

Cotton, D. R. E., Warren, M. F., Maiboroda, O., & Bailey, I. (2007). Sustainable development, higher education and pedagogy: A study of lecturers’ beliefs and attitudes. Environmental Education Research, 13(5), 579–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701659061

Edin, M. (2003). State capacity and local agent control in China: CCP cadre management from a township perspective. The China Quarterly, 173, 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009443903000044

Ferreira, J. (2009). Unsettling orthodoxies: Education for the environment/for sustainability. Environmental Education Research, 15(5), 607–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903326097

Fiselier, E. S., Longhurst, J. W. S., & Gough, G. K. (2018). Exploring the current position of ESD in UK higher education institutions. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 19(2), 393–412. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-06-2017-0084

Fowler, F. C. (2000). Policy studies for educational leaders: An introduction. Merrill. https://books.google.com.hk/books?id=B-KeAAAAMAAJ

Franco, I., Saito, O., Vaughter, P., Whereat, J., Kanie, N., & Takemoto, K. (2019). Higher education for sustainable development: Actioning the global goals in policy, curriculum and practice. Sustainability Science, 14(6), 1621–1642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0628-4

González-Gaudiano, E. J. (2016). ESD: Power, politics, and policy: “Tragic optimism” from Latin America. The Journal of Environmental Education, 47(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2015.1072704

Hayles, C. S. (2019). INSPIRE sustainability internships: Promoting campus greening initiatives through student participation. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(3), 452–469. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-03-2019-0111

Hopkins, C., & McKeown, R. (2003). Education for sustainable development: An international perspective. In Education and sustainability: Responding to the global challenge (Vol. 4, p. ijshe.2003.24904bae.007). ROSSEELS

Hopkinson, P., Hughes, P., & Layer, G. (2008). Sustainable graduates: Linking formal, informal and campus curricula to embed education for sustainable development in the student learning experience. Environmental Education Research, 14(4), 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802283100

Katayama, J., Örnektekin, S., & Demir, S. S. (2018). Policy into practice on sustainable development related teaching in higher education in Turkey. Environmental Education Research, 24(7), 1017–1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1360843

Kovaleva, T. N., Maslova, Y. V., Kovalev, N. A., Karapetyan, E. A., Samygin, S. I., Kaznacheeva, O. K., & Lyashenko, N. V. (2019). Ecohumanistic education in Russia and China as a factor of sustainable development of modern civilization. Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valore, 6, 1–23.

Kuzich, S., Taylor, E., & Taylor, P. C. (2015). When policy and infrastructure provisions are exemplary but still insufficient: Paradoxes affecting education for sustainability (EfS) in a custom-designed sustainability school. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 9(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408215588252

Læss⊘e, J. (2010). Education for sustainable development, participation and socio-cultural change. Environmental Education Research, 16(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903504016

Li, P. (1996). Outline of the ninth five-year plan (1996–2000) for National economic and social development and the long-range objectives to the year 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2021, from http://www.china.org.cn/95e/95-english1/2.htm

Li, C. (2018). The sustainable development education and Chinese experiences. Journal of Northwest Normal University (social Sciences), 55(2), 73–82.

Lozano, R. (2010). Diffusion of sustainable development in universities’ curricula: An empirical example from Cardiff University. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(7), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.07.005

Lozano, R., Ceulemans, K., Alonso-Almeida, M., Huisingh, D., Lozano, F. J., Waas, T., Lambrechts, W., Lukman, R., & Hugé, J. (2015). A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.048

Lu, S., & Zhang, H. (2013). A comparative study of education for sustainable development in one British university and one Chinese university. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 15(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-11-2012-0098

Luo, J. M., Ngok, L., & Qiu, H. (2018). Education for sustainable development in Hong Kong: A review of UNESCO Hong Kong’s experimental schools. 8.

Martin, S., Dillon, J., Higgins, P., Peters, C., & Scott, W. (2013). Divergent evolution in education for sustainable development policy in the United Kingdom: Current status, best practice, and opportunities for the future. Sustainability, 5(4), 1522–1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5041522

McKeown, R., Hopkins, C. A., Rizi, R., & Chrystalbridge, M. (2002). Education for sustainable development toolkit environment and resources center. University of Tennessee Knoxville.

Mcmillin, J., & Dyball, R. (2009). Developing a whole-of-university approach to educating for sustainability: Linking curriculum, research and sustainable campus operations. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 3(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/097340820900300113

Nicolaides, A. (2006). The implementation of environmental management towards sustainable universities and education for sustainable development as an ethical imperative. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 7(4), 414–424. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370610702217

Nomura, K., & Abe, O. (2009). The education for sustainable development movement in Japan: A political perspective. Environmental Education Research, 15(4), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903056355

Orr, D. (1994). Environmental literacy: Education as if the earth mattered. Human Scale Education.

Paletta, A., & Bonoli, A. (2019). Governing the university in the perspective of the United Nations 2030 Agenda: The case of the University of Bologna. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(3), 500–514. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2019-0083

Qi, T. (2011). Moving toward decentralization? Changing education governance in China after 1985. In A. W. Wiseman & T. Huang (Eds.), The impact and transformation of education policy in China (pp. 19–41). Emerald Group Publishing.

Qian, J., Wang, Y., & Li, F. (2019). Establishing transdisciplinary minor programme as a way to embed sustainable development into higher education system: Case by Tongji University, China. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(1), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-05-2018-0095

Rauch, F., & Steiner, R. (2006). School development through education for sustainable development in Austria. Environmental Education Research, 12(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620500527782

Saqib, Z. A., Zhang, Q., Ou, J., Saqib, K. A., Majeed, S., & Razzaq, A. (2020). Education for sustainable development in Pakistani higher education institutions: An exploratory study of students’ and teachers’ perceptions. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21(6), 1249–1267. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-01-2020-0036

Savelyeva, T., & Douglas, W. (2017). Global consciousness and pillars of sustainable development: A study on self-perceptions of the first-year university students. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 18(2), 218–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-04-2016-0063

Scott, W. (2015). Education for sustainable development (ESD): A critical review of concept, potential and risk. Schooling for Sustainable Development in Europe, 47–70.

Stables, A., & Scott, W. (2002). The Quest for Holism in Education for Sustainable Development. Environmental Education Research, 8(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620120109655

Sterling, S., & Scott, W. (2008). Higher education and ESD in England: A critical commentary on recent initiatives. Environmental Education Research, 14(4), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802344001

Strategy for invigorating China through science and education. (2019). China Keywords. Retrieved April 6, 2019 from http://www.china.org.cn/english/china_key_words/2019-04/16/content_74687671.htm.

Summers, M., Childs, A., & Corney, G. (2005). Education for sustainable development in initial teacher training: Issues for interdisciplinary collaboration. Environmental Education Research, 11(5), 623–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620500169841

Tan, H., Chen, S., Shi, Q., & Wang, L. (2014). Development of green campus in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 64, 646–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.019

Tilbury, D. (2007). Monitoring and evaluation during the UN decade of education for sustainable development. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 1(2), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/097340820700100214

UNESCO. (2014). UNESCO roadmap for implementing the global action programme on education for sustainable development. UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2015). Education 2030 framework for action. UNESCO.

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1

UNESCO. (2020). Global education monitoring report 2020: Inclusion and education‐All means all. Paris: UNESCO.

Wang, J., Yang, M., & Maresova, P. (2020). Sustainable Development at higher education in China: A comparative study of students’ perception in public and private universities. Sustainability, 12(6), 2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062158

Weiss, M., & Barth, M. (2019). Global research landscape of sustainability curricula implementation in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(4), 570–589. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-10-2018-0190

Yang, G., Lam, C.-C., & Wong, N.-Y. (2010). Developing an instrument for identifying secondary teachers’ beliefs about education for sustainable development in China. The Journal of Environmental Education, 41(4), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960903479795

Yao, C. (2018). How a blended learning environment in adult education promotes sustainable development in China. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 58(3), 480–502.

Yao, C. (2019). An investigation of adult learners’ viewpoints to a blended learning environment in promoting sustainable development in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 220, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.290

Yuan, X., & Zuo, J. (2013). A critical assessment of the higher education for sustainable development from students’ perspectives – a Chinese study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 48, 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.10.041

Zhang, T. (2010). From environment to sustainable development: China’s strategies for ESD in basic education. International Review of Education, 56(2–3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9159-7

Zhou, D. (2021). Explore the notion of education for sustainable development in early childhood education in China. Pacific Early Childhood Education Research Association, 15(1), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.17206/apjrece.2021.15.1.77

Acknowledgments

We thank Geoff Whyte, MBA, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Tohoku University-Tsinghua University Collaborative Research Fund 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, ZZ and GL; Methodology, ZZ, GL; Data collection, GL; Data analysis and interpretation: GL and ZZ; Writing—original draft preparation, GL and YX; Writing—review and editing, YX and ZZ; Supervision, ZZ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, G., Xi, Y. & Zhu, Z. The way to sustainability: education for sustainable development in China. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 23, 611–624 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09782-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09782-5