Abstract

This study examined the influence of concurrent racism and sexism experiences (i.e., gendered racism) on African American women’s suicidal ideation and behavior in the context of disadvantaged socioeconomic status. Drawing on a stress process framework, the moderating effects of ethnic identity and skin color were explored using multiple regression analyses. Data were from 204 low-income African American women in the B-WISE (Black Women in a Study of Epidemics) project. Findings suggested that experiencing gendered racism significantly increased these women’s risk for suicidal ideation or behavior, though only among women with medium or dark skin color. Also, having strong ethnic identity buffered the harmful effects of gendered racism. The moderating properties of skin color and ethnic identity affirmation likely operate through psychosocial pathways, blocking internalization of negative stereotypes and reducing the level of distress experienced in response to gendered racism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past three decades, there have been alarming spikes in suicide in African American populations. Between 1981 and 1994, the suicide rate for African Americans 18–29 increased by 169 %, while the rate for European Americans in the same age group rose by only 18 % during this period (CDC 2011). Though the incidence of suicide-related mortality for both European and African American women is low (about 6.2 and 2.1 per 100,000, respectively; CDC 2011), the rate of suicide attempt is higher for women than for their male counterparts (Joe et al. 2006). African American women have the highest rate of medically treated suicide attempts, defined as attempts with consequences severe enough to require medical intervention (Spicer and Miller 2000). This pattern suggests that African American women may engage in more serious self-harm than women of other races, constituting a significant public health concern.

A Conceptual Model of Suicide Risk in Low-Income African American Women

We currently have a limited understanding of the combinations of culturally specific experiences and social psychological characteristics associated with suicide risk and resiliency among African American women, prompting calls for additional research in this area (Joe et al. 2006; Poussaint and Alexander 2000). The existing literature points to the fundamental role of social statuses in the patterning of mental health outcomes, with differential exposure to stressors and access to coping resources as intervening mechanisms (Phelan et al. 2010). We employ a stress process framework to conceptualize the influence of race and gender-related stressors on suicidal ideation and behavior. There is ample support for this approach to suicide research, with a number of empirical studies demonstrating linkages between stressful life events (e.g., widowhood or job loss) or chronic strain (e.g., poverty or family discord) and suicidal ideation or behavior (Conwell et al. 2002; Dube et al. 2001; Evans et al. 2004; Maris 1997; Moscicki 1997). For example, using a large epidemiological dataset, Feskanich et al. (2002) found a nearly fivefold increase in risk of suicide among women in a high stress category relative to those reporting low stress.

Importantly, “the stressors to which African American women are exposed and their appraisals of stressors reflect this population’s distinct history, sociocultural experiences, and position in society (Woods-Giscombe and Lobel 2008: 173).” Because gender, race, and SES influence degree of exposure, experiences, and reactions to stressors (Foreman et al. 1997; Jackson 2002; Jackson et al. 2005; Pearlin 1999; Wethington et al. 1987), it is critical to develop models that are tailored specifically to vulnerable race/gender/class subgroups. To address this gap in the literature, we test a model of suicide risk and resilience among low-income African American women that is rooted in theories of stress and coping. We argue that racist and sexist life events constitute unique stressors for low-SES African American women, who are in a vulnerable position of structural disadvantage with respect to race, class, and gender. Those who experience higher levels of discrimination and threats to their self-esteem, sense of control, and positive racial and gender identity may be more likely to turn to suicide as an expression of frustration or as a potential relief from their difficult circumstances.

Yet, many low-income African American women are resilient in the face of persistent racism and sexism. We draw on stress theory and moderating factors to explain why some women in this position are at greater risk for suicidality than others. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) argue that resources operate through (1) modifying situations that give rise to stress; (2) influencing the meaning of stressors such that they become less threatening; or (3) reducing the level of psychological distress that occurs in response to the stressor. Thus, stressors should have a substantially reduced effect in the presence of these resources, which allow individuals to effectively manage or neutralize stress before it affects physical or psychological health.

Social psychologists emphasize that the efficacy of coping resources depends on the match between the psychosocial characteristic or trait and the nature of the stressor (Lazarus 1999; Morrison and O’Connor 2005). When examining how women cope with race and gender-related stressors, it is critical to consider mechanisms that could influence racial and gender identity and experiences. Consistent with this idea, we include ethnic resources (i.e., ethnic identity achievement and affirmation, as well as participation in ethnic communities and cultural experiences) in our conceptual model as potential protective factors for suicide among low-SES African American women. For instance, having pride about being African American might enable women to reframe a racist slight as the behavior of an ignorant individual rather than a valid threat to her self-worth, reducing the stress response to such events. In contrast, ethnic pride would probably not be an effective protectant when experiencing a stressor such as marital discord, while valuing one’s role as a spouse might be.

Likewise, our model incorporates the moderating effects of skin color. Colorism (i.e., the privileging of lighter over darker skin within a racial group) and its link to the feminine beauty ideal have important and understudied influences on African American women’s racial and gender identities. By examining skin color, we are not attempting to reduce the effects of racism to “blacker” or “whiter.” We acknowledge that the social construction of racial phenotypes is more complex than this. Rather, we meaningfully consider the importance of skin color for people’s racial and gender experiences and identities. Because skin color has been shown to be a particularly salient factor for low-SES women of color relative to African American men or affluent African American women (Thompson and Keith 2001), this trait is an important component of our conceptual model. In sum, while our set of moderators is not intended to be exhaustive, ethnic resources and skin color are excellent candidates for protective factors against race and gender-related stressors since they impact how African American women experience race, class, and gender in the U.S.

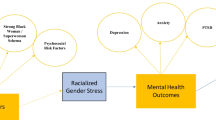

The conceptual model described above is presented in Fig. 1 and is derived from Pearlin’s (1999) theory and depiction of the stress process involving stressors, moderating resources, and mental health outcomes in the context of social and economic statuses. In what follows, we review the literature supporting relationships outlined in this model. Then, we present results testing these relationships using data from 204 primarily low-income African American women in the B-WISE (Black Women in the Study of Epidemics) project.

A stress model of suicide in low-income African American women (adapted from Pearlin 1999)

Gendered Racism and Suicide Risk

There has been very little research investigating risk and protective factors for suicide among low-income African American women, and no studies have empirically linked racism or sexism experiences to suicidal ideation or behavior. Thus, we look to the broader literature on mental health consequences of racial and gendered stressors for guidance. Since depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychological distress, and other mental health problems are strongly correlated with suicidal ideation and behavior (Kessler et al. 2001; Moscicki 2001), we expect to identify similar mechanisms and base our expectations of the relationship between race and gender-related stressors and suicide outcomes on this body of research.

According to Brown (2003), adverse mental health outcomes among African American women may be linked to stress associated with the intersection of gender, racial, and socioeconomic disadvantages relative to more privileged social statuses. Here, we argue that low-SES African American women’s experiences of racism and sexism constitute stressors that increase suicidality, though the impact of these stressors may be contingent on levels of culturally specific risk and protective factors. Low-SES African Americans are disproportionately vulnerable to major racist life events like employment discrimination (Clark et al. 1999; Foreman et al. 1997). Also, some research suggests that SES moderates the impact of racism on health outcomes such that it has a stronger effect among low-SES African Americans relative to high-SES African Americans or other race-SES subgroups (Feagin 1991). Thus, low-SES African American women are probably exposed to more overt racism than those who are socioeconomically advantaged and may also possess fewer resources with which to cope with these stressors (Feagin 1991; Foreman et al. 1997; Pearlin 1999).

Anderson’s (1991) theory of acculturative stress and Clark and colleagues' (1999) biopsychosocial model integrate research on social psychological aspects of racism and acculturation with traditional perspectives on social stress and psychopathology. Anderson (1991) argues that “conflicts in values, beliefs, and patterns of behavior lead to tensions between two or more autonomous cultures” (p. 696). In the U.S., African American cultural values and behaviors are often undervalued or at odds with the dominant European American culture, resulting in persistent threats to the self-concept and ethnic identity of African Americans.

While episodic stress derives from discrete and relatively infrequent experiences of direct racism and sexism, African American women are also vulnerable to daily hassles in the form of more subtle and often unintentional degradations and exclusions (Harrell 2000). Termed microaggression, brief and subtle verbal, behavioral, and environmental slights and insults by European Americans toward African Americans have been called the “new face of racism” (Sue et al. 2008). The psychological effects of these experiences on African Americans are particularly harmful because the individual is left to decipher the perpetrator’s message and may question their own perceptions. Likewise, the “invisibility syndrome” has been used to describe the effects of dominant negative attitudes and stereotypes that conceal the talents, contributions, and true identities of African Americans, leading to considerable stress and confusion about being African American and about one’s place in the world (Franklin et al. 2006).

The stress associated with racial microaggressions as well as more over forms of racism has significant adverse consequences for African Americans (Brown 2003; Clark et al. 1999; Utsey and Hook 2007; Williams and Williams-Morris 2000). Substantial empirical research has linked racism experiences to psychological distress and depression (Jackson et al. 1996; Kessler et al. 1999; Landrine and Klonoff 1996; Sellers et al. 2003) and has suggested that these are more powerful risk factors than other kinds of stressful life events (Utsey et al. 2008). Scholars have documented the traumatic nature of racist incidents and challenged traditional conceptions of PTSD, urging psychologists to broaden their conceptualization to encompass racism as a psychosocial stressor (Bryant-Davis 2005; Sanchez-Hycles 1999).

African American women experience microaggressions and stress on the basis of both race and gender. This phenomenon has been termed racialized sexism (Hooks and Mesa-Bains 2006), as well as gendered racism (Thomas et al. 2008). African American women experience a unique form of double jeopardy (Beale 1995) that involves sexual objectification, second-class citizenship, and assumed inferiority across multiple settings outside of their communities (Sue 2010). For African American women, efforts to cope with simultaneous racism and sexism (hereafter termed gendered racism) require substantial identity and emotion work, often resulting in high levels of stress and depression (Jones and Shorter-Gooden 2003). For African American women, gendered racial identity has greater salience compared to the separate constructs of racial or gender identity, indicating that both of these social statuses simultaneously influence perceptions of self and psychological distress (Thomas et al. 2011). Quantitative research supports these findings, suggesting that racism and sexism experiences are highly correlated and that African American women are more likely to experience and be distressed by sexism (Klonoff and Landrine 1995; Landrine et al. 1995) and racism (Greer et al. 2009; Moradi and Subich 2003) than European American women and African American men, respectively.

When examined as separate constructs, the adverse effects of racism and sexism have received mixed support. Some studies have found that when racism and sexism are examined as separate predictors of psychological distress among African American women, sexism emerges as the only significant correlate (Moradi and Subich 2003; Szymanski and Stewart 2010). However, King (2003) found that racism and the interaction of racism and sexism are significant correlates of psychological distress among African American women. Furthermore, Krieger (1990) found that both racism and sexism result in adverse health outcomes for African American women. As a result of these mixed findings, scholars have suggested examining racism and sexism as a single construct (Moradi and Subich 2003). Among the few studies that have examined gendered racism, results demonstrate adverse mental health consequences for African American women, increasing psychological distress and symptoms of PTSD (Buchanan and Fitzgerald 2008; Moradi and Subich 2003). Therefore, African American women who perceive both racism and sexism appear to be at an increased risk for psychological distress, potentially leading to suicidal ideation and behavior.

The Protective Role of Ethnic Resources

For African Americans, who have historically been subjected to racial and economic oppression, culturally specific resources may be uniquely relevant (Gibbs 1997). Early in the development of theories of race and ethnicity, Du Bois (1903) recognized the importance of racial identity and attitudes in determining African Americans’ well-being. It is from the interplay between one’s own racial identity and broader European American society that the meaning and impact of being African American are constructed (Sellers et al. 2003). While exposure to racism can influence the meaning of being African American, so, too, can cultural experiences and subjectivities stemming from African Americans’ historical and contemporary circumstances. In other words, a strong and positive racial identity and community can alter the effects of racism on African Americans’ self-concepts and level of distress, blocking internalization of negative racial stereotypes and experiences. Thus, culturally specific psychosocial factors may be a key resource, having the potential to buffer the adverse impact of stressors associated with disadvantaged statuses (Scott 2003; Sellers et al. 2006).

Positive ethnic identity—feeling connected to one’s ethnic heritage and having an affirmative sense of pride and belonging to one’s ethnic group—has been identified as protective of mental health among African Americans. Ethnic identity is a multidimensional construct that includes ethnic group behaviors, as well as knowledge and awareness of cultural beliefs and traditions of one’s ethnic group (Phinney and Ong 2007). Phinney (1992) identifies ethnic behaviors and practices, affirmation and belonging, and ethnic identity achievement as critical components of ethnic identity development. A strong ethnic identity helps neutralize feelings of marginalization and devaluation that may develop in response to status-based threats to a positive self-concept (Outten et al. 2009; Verkuyten 2010). Thus, ethnic and other culturally specific resources may be uniquely relevant and salient for socioeconomically disadvantaged African Americans confronting racism-related stressors.

Empirical research provides evidence that ethnic identity and cultural practices can act as stress buffering mechanisms. Simply exploring one’s ethnic identity was recently found to enhance psychological well-being in a large sample of minority adults (Ghavami et al. 2011). Other research suggests that positive ethnic identity moderates the effects of race-related stress on psychological well-being (Iwamoto and Liu 2010; Utsey et al. 2008) and on depression with suicidal ideation among African American adults (Walker et al. 2008). In addition, positive ethnic identity is inversely related to the internalization of societal beauty ideals among African American young adult women (Rogers Wood and Petrie 2010). These findings support the need for an examination of ethnic identity as a stress buffering mechanism.

Skin Color and Colorism

Skin color may also play a role in the stress process for socioeconomically disadvantaged African American women. Differences in skin tone often give rise to colorism, or preferences for light complexion within a racial or ethnic group (Bodenhorn 2006; Hochschild and Weaver 2007; Keith and Thompson 2003). Systematic complexion advantages accruing to lighter skin African Americans date back to slave trade in the U.S. and persist today (Lake 2003; Russell et al. 1993). The American media has fueled negative stereotypes and discrimination through the portrayal of African Americans with dark skin as lacking civility, having lower intelligence, and being less than human (Feagin 2001). These stereotypes and the legacy of the American slave trade have produced a socioeconomic color gradient in the U.S. such that African Americans with lighter skin have higher levels of income, occupational prestige, and education than those with dark skin, on average, as well as higher marriage rates (Hunter 1998; Keith and Thompson 2003; Hochschild and Weaver 2007).

In addition, light skin and associated European American features are central components of the American feminine beauty ideal (Patton 2006). Definitions of beauty are socially constructed, varying across time and cultures. Beauty ideals reflect and reproduce racial, socioeconomic, and gender stratification, with marginalized and less powerful groups being held to the physical standards of the privileged European American majority (Saltzberg and Chrisler 1997). In the U.S., research suggests that lighter skin is perceived as more attractive than darker skin and Afrocentric characteristics by the majority of Americans, regardless of race (Bond and Cash 1992; Maddox 2004). Consequently, African American women with darker skin are oppressed on the basis of both race and nonconformity with the racist feminine beauty ideal. Given the role of colorism in structuring educational attainment and income, economic strain and classism add additional elements of risk for darker women of color.

The effects of skin color on the stress process and mental health may work through at least two mechanisms. First, because African American women with darker skin are afforded less social status and prestige than their lighter peers, they may be more likely to internalize negative stereotypes and prejudices. Using data from the National Survey of Black Americans, Thompson and Keith (2001) found that women with darker skin have lower self-esteem, especially if they have lower SES. These findings suggest that women with darker skin may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of racism and sexism if they do not possess social psychological coping resources. Additionally, darker African Americans may be more likely to perceive or experience discrimination and other race-related stressors than their lighter counterparts, increasing the impact of these experiences on health outcomes (Keith and Herring 1991; Klonoff and Landrine 2000). For example, using data from the Detroit Area Study, Hersch (2006) found that African Americans with light skin report substantially better treatment by European Americans than those with medium or dark skin, and they attributed this behavior to their light skin color.

In sum, though the relationship between racism and mental health is well-established, empirical research has rarely been extended to suicidal ideation or behavior. In addition, there have been numerous recent calls for research exploring risk and protective factors for suicide in African American women, noting a particular need to understand “culturally relevant factors…beyond social support and religiosity (Walker 2007, p. 389).” To address these gaps in knowledge, we explore the effects of gendered racism experiences on socioeconomically disadvantaged African American women’s suicidal ideation and behavior, focusing on the moderating role of ethnic resources and self-reported skin color. Based on the research reviewed above, we expect to find that gendered racism is associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior and that this relationship is stronger among women reporting medium-to-dark skin and those lacking ethnic resources. Understanding how skin color may impact the appraisal of stress and overall psychological well-being of low-SES African American women is a significant contribution toward the assessment and prevention of suicide risk in this vulnerable population. Furthermore, this research presents a challenge to public health professionals in drawing attention to the role of colorism, an emerging focus in health research.

Method

Participants

Data used in these analyses were from the first wave of the B-WISE (Black Women in the Study of Epidemics) project, which was conducted by an interdisciplinary research team at the University of Kentucky. This study measured risk and protective factors in the epidemiology of African American women’s health outcomes. Parallel data were collected from prisoners and probationers to make comparisons across criminal justice status. The total sample size is 643, but only the community sample was used in these analyses (n = 206).

After dropping two cases due to random missing data, the final analysis sample contained 204 observations. Mean age was 36.39 years. Mean years of education was 12.75, with 20 % of respondents reporting a high school diploma or GED; 39 %, some college or technical school; and 15 %, a college degree or higher. The mean annual household income was $20,850. About 56 % of the women in the sample reported working full- or part-time for pay, and 25 % indicated that a spouse or romantic partner contribute money to their household income. Only about 13 % of the women in the sample were married, but 56 % were in a relationship.

Recruitment

Recruitment for the community sample was conducted using newspaper ads and fliers posted in various communities with a large African American population in Kentucky. Eligibility criteria included: (1) self-identifying as an African American woman; (2) being at least 18 years old; and (3) not currently being in the criminal justice system. In addition, because of the high rate of drug use among prisoners, substance-using women were oversampled. A stratified sampling procedure was used to recruit drug users and non-users (based on self-report data) until a target sample of 100 women in each cell was reached. Eligible women participated in face-to-face interviews conducted by trained female African American interviewers in a private location.

Measures

Suicidality

Suicidal ideation or behavior was measured using a dichotomous variable. This was coded from two survey items asking whether a respondent had ever (1) experienced “serious thoughts of suicide,” including having a plan for taking her own life (suicidal ideation) and (2) had carried out suicidal gestures or attempts (suicidal behavior). Response options for these two survey items were “yes” or “no.” The dichotomous variable was coded 1 if suicidal ideation or behavior was reported, and 0 if neither. Suicidal ideation and behavior were combined because the small proportion of respondents who had attempted suicide (9 %) may lead to biased logistic regression estimates.Footnote 1

Gendered Racism

Experiences of gendered racism were measured using the Schedule of Sexist Events (SSE; Klonoff and Landrine 1995) and the Schedule of Racist Events (SRE; Landrine and Klonoff 1996). These instruments contained 13 and 17 items, respectively. They asked whether respondents ever experienced a series of events “because you are a woman” or “because you are black” (e.g., unfair treatment by employers, teachers, coworkers, neighbors, friends, partners/significant others, etc.). These were combined into one scale of lifetime gendered racism experiences because (1) existing research and theory suggests that it is often difficult to distinguish whether unfair treatment is due to race or gender (e.g., King 2003; Thomas et al. 2008; (2) the racism and sexism scales were highly correlated (r = 0.61, p < 0.001) and contain numerous identical items that are strongly associated; (3) when included separately in regression models, there was evidence of multicollinearity; (4) both scales were significant predictors of suicidality when included in two separate regression models. These analyses and additional information about scale coding are available upon request (also see Perry et al. 2012). The combined gendered racism scale is highly reliable, with an alpha of 0.90.

The mean lifetime SSE and SRE scores in our sample were 40.04 and 33.94, respectively. These were significantly different (p < 0.001) from the means of 50.80 and 43.19 reported by scale creators Klonoff and Landrine (1995, 1999) using samples of 228 women of color and 277 African American women, respectively. The women in our sample had lower levels of education and income than the samples described by these authors, which may explain the lower perceptions of sexism and racism. If racism and sexism experiences in our sample were less frequent compared to the general population of African American women, these analyses may have underestimated the effects of gendered racism on suicidal ideation and behavior.

Socio-Demographic and Mental Health Variables

Socioeconomic status (SES) and mental health status were included as control variables in models predicting suicidality. Some research has demonstrated a positive relationship between SES and suicide, and SES may also play a role in vulnerability to and perceptions of racism (Agerbo et al. 2002; Agerbo et al. 2006; Foreman et al. 1997; Sigelman and Welch 1991a, b). Moreover, suicidal ideation and behavior are key features of some psychiatric disorders, and over 90 % of suicide victims had depression or some other psychiatric illness (Agerbo et al. 2002, 2006; Moscicki 2001).

Education and household income were employed as measures of SES. Education was coded in years, with annual household income coded in thousands of dollars. Alternative strategies for coding and operationalization were explored (e.g., personal income, being on public assistance, work status, education level as dichotomous variables representing degrees), but did not improve model fit and did not change the results of the analysis. In addition, age was initially included as a control variable, but was dropped from final models due to non-significance.

Two dichotomous variables measured mental health and substance abuse history. These were coded 1 if a respondent reported that she had a lifetime history of (1) illicit drug problems, abuse, or dependence and (2) nervous or mental health problems. Response categories for the original survey items were “yes” and “no.” A variety of different measures of illicit drug use (e.g., past year and past month drug use) and mental health problems (e.g., self-reported anxiety and depression) were initially included in regression analyses. However, the two variables described above were retained in final models because choice of measures did not impact the effects of other independent variables.

Ethnic Resources

Aspects of ethnic identity were captured using the multigroup ethnic identity measure (Phinney 1992). This measure was comprised of 10 items with response to categories ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”) and contained two distinct subscales. The ethnic affirmation subscale assessed the degree to which individuals feel a sense of ethnic belonging and pride (α = 0.90). It contained items such as “I feel good about my cultural or ethnic background,” and “I feel a strong attachment toward my own ethnic group.” The ethnic identity achievement subscale measured the extent to which one acknowledges and understands the lived and historical meaning of their ethnic identity (α = 0.73). Items included “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means to me,” and “I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs.”

In addition, Phinney’s (1992) measures of ethnic behavior, which were combined in the original subscale, were included as two separate dichotomous variables because they are conceptually distinct. These measured whether a respondent (1) was a member of an ethnic community (i.e., participated in organizations or social groups primarily comprised of or practiced by members of one’s own ethnic group) and (2) participated in cultural practices specific to one’s ethnic group. Because the original response categories for these two variables ranged from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”), these could have been included in the models as a series of dichotomous variables. However, these categories were collapsed into one dichotomous variable per measure to increase model degrees of freedom. These variables never achieved significance regardless of how they were coded, and choice of dichotomous variable coding did not alter other regression results.

Self-Reported Skin Color

A dichotomous variable measuring self-reported skin color was coded 1 if the respondent felt they had “light” or “very light” skin and 0 if the respondent identified their coloring as “medium,” “dark,” or “very dark.” Because only 3 women reported very light skin and 2 reported very dark skin, these were combined with larger adjacent categories to avoid problems with small cell sizes. Also, a Wald test for equality of coefficients suggested that the effects of medium and dark skin were statistically indistinguishable (X 2 = 0.02, p = 0.89). The medium (49 % of respondents) and dark (21 % of respondents) categories were combined because collapsing categories facilitated the interpretation of moderation results.

Analysis

Analyses presented here examined relationships between gendered racism experiences, ethnic resources, and suicidal ideation and behavior. Comparisons to Census data suggest that the B-WISE sample is not representative of African American women nationally. Specifically, results presented here were based on a sample with a lower SES and marriage rate than all African American women living in the U.S. In addition, because of the stratified sampling technique, about 50 % of the sample reported past year illegal drug use.Footnote 2 Since the high number of drug users in the sample could introduce bias, a dichotomous variable indicating whether the respondent had a self-reported history of illicit drug problems was included in all models. SES and marital status were also included to correct for the non-representative sample, though these controls did not change substantive findings.

Relationships between covariates were assessed using Pearson’s correlations for two continuous variables, t-tests for one binary and one continuous variable, and Chi-square tests for two binary variables. To determine the extent to which gendered racism predicts suicidal ideation or behavior, binary logistic regression models were computed using Stata 11. A baseline model regressed suicidality on the gendered racism life events scale, controlling for SES and mental health variables. If gendered racism had a significant effect on suicidality when SES and mental health variables were included in the model, it could be determined that the explanatory power of gendered racism was not confounded by or attributable to the relationship between SES or mental health and perceived gendered racism experiences. Next, ethnic resources and skin color were added to the baseline model, allowing for the identification of potential mediating relationships. For this full model, variance inflation factors were calculated to assess multicollinearity. These suggested that the level of collinearity was not problematic.

To explore whether ethnic resources moderated the relationship between gendered racism and suicidality, models with interaction terms were explored. These determine whether gendered racism had unique effects at different levels of a given covariate. One set of multiplicative terms (gendered racism*categorical covariate) was added to the baseline model, and this was repeated for each covariate. Consistent with the dummy variable method, categorical variables were created for continuous covariates by dividing the distribution into three approximately equal groups using tertiles. Where two groups demonstrated a similar effect of gendered racism, they were combined. Only models with significant interaction terms were presented in tables and text.Footnote 3 To facilitate the interpretation of interactive models, figures of predicted probabilities at each level of the moderating variable were presented following the regression results.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on independent and dependent variables. Measures of association revealed significant relationships between some of these covariates. Years of education and household income were positively correlated (r = 0.30, p < 0.001). Women with higher levels of education (t = 2.61, p < 0.01) and household income (t = 2.07, p < 0.05) were more likely to report a history of drug problems. Mental illness and drug abuse history were also associated (X 2 = 9.51, p < 0.01). Higher levels of education were also associated with belonging to ethnic community (t = −2.06, p < 0.05) and strong ethnic practices (t = −2.81, p < 0.01).

In addition, all measures of ethnic resources and skin color were significantly related. Ethnic identity achievement and affirmation were positively correlated (r = 0.69, p < 0.001). Ethnic identity achievement was associated with belonging to an ethnic community (t = −5.21, p < 0.001) and engaging in strong cultural practices (t = −7.20, p < 0.001), as is ethnic affirmation (t = −9.90, p < 0.001; and t = −4.06, p < 0.001, respectively). Likewise, women who belonged to an ethnic community were more likely to report strong cultural practices (X 2 = 12.31, p < 0.001). Finally, women with self-reported medium-to-dark skin had higher levels of ethnic affirmation (t = 2.49, p < 0.05) and ethnic identity achievement (t = 2.97, p < 0.01) and were more likely to report strong cultural practices (X 2 = 4.30, p < 0.05).Footnote 4

Table 2 presents results from logistic regression models examining the effects of gendered racism and ethnic resources on suicidal ideation and behavior. According to Model 1, experiencing additional gendered racism events was associated with a significant increase in the odds of reporting suicidal thoughts or behaviors (OR = 1.06, p < 0.01), controlling for socioeconomic and mental health status. Also, higher levels of household income were associated with lower odds of suicidality (OR = 0.97, p < 0.05), and women with a self-reported history of mental health problems were predicted to be over three and a half times more likely than those without to experience suicidal thoughts or behaviors (OR = 3.56, p < 0.01). Neither education nor drug problems achieved statistical significance.

The effects of ethnic resources are presented in Models 2–4 (See Table 2). According to Model 2, none of the measures of ethnic resources were statistically significant, providing no evidence that these had a direct effect on suicide risk in the current sample. However, there were significant interactions between gendered racism experiences and both ethnic affirmation and skin color. Specifically, we found that strong feelings of ethnic affirmation and belonging moderated the adverse effects of gendered racism on suicidality (p < 0.05; see Model 3). As depicted in Fig. 2, gendered racism had a very modest positive influence on the predicted probability of suicidal ideation and behavior among low-SES African American women with high levels of ethnic affirmation, and a very strong effect for those with moderate to low levels of affirmation.

Moreover, findings in Model 4 (See Table 2) provide evidence that gendered racism had differential effects on suicidality for low-SES African American women who self-reported light skin relative to those with medium-to-dark skin (p < 0.01). Specifically, additional gendered racism experiences had a modest negative relationship to suicidal ideation and behavior such that African American women with lighter skin reporting high levels of gendered racism had a predicted probability of suicidality that approached zero (see Fig. 3). Alternatively, gendered racism had a strong, nearly linear adverse influence among women reporting medium-to-dark skin, such that those at the highest levels had a predicted probability of suicidality of about 75 %.

In attempt to explain the moderating effect of skin color, the relationship between skin color and gendered racism experiences was examined using a two-sample t test. Findings suggested that low-SES African American women with medium-to-dark skin reported levels of gendered racism that were not significantly different from women with light skin (t = 0.74, p = 0.46). However, compared to women with light skin, those with medium-to-dark skin reported significantly higher levels of positive feelings toward their ethnic group (t = 2.37, p < 0.05) and stronger ethnic identity achievement (t = 3.14, p < 0.01).

Discussion

Our findings point to a strong, positive association between negative life events attributed to gendered racism and risk for suicidality among socioeconomically disadvantaged African American women. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Agerbo et al. 2002, 2006; Moscicki 2001), these results suggest that even in this relatively low-income sample, those with higher SES were at lower risk for suicidality. Also, those with a history of mental health problems were over three times as likely as those without to report suicidal ideation or behavior. However, gendered racism exerted a substantial independent effect on suicidality above and beyond the predictive power of SES and mental health history, reducing concerns about the potential confounding influence of these factors.

The effect of gendered racism in the current study provides additional empirical evidence linking African Americans’ experiences of racism to mental health problems (e.g., Jackson et al. 1996; Kessler et al. 1999). Gendered racism may operate through social psychological pathways, causing women to internalize negative stereotypes that threaten a positive self-concept, sense of control, proactive coping, and other social psychological resources (Aneshensel et al. 1991; Wallace et al. 2011). In addition, as a source of stress, gendered racism may have direct adverse effects on cognitive and emotional functioning through psychobiological pathways (e.g., acute neuroendocrine response, allostatic load; Massey 2004). It is important to note that distress and related psychosocial outcomes are a normative response to systematic oppression in racist and sexist societies and do not reflect deficits or failures on the part of individual women. As a pervasive feature of the social condition of socioeconomically disadvantaged African American women, gendered racism experiences may shape biological and psychological processes in ways that impact health trajectories and well-being.

Ethnic Protective Factors

Existing research suggests that culturally specific psychosocial factors may be a key resource for racial/ethnic minorities, potentially moderating the adverse effects of stressors associated with their disadvantaged status (Rogers Wood and Petrie 2010; Scott 2003; Sellers et al. 2006; Utsey et al. 2008; Walker et al. 2008). Along these lines, Walker (2007) attributes the recent rise in suicide rates among African Americans to acculturation, arguing that adopting the cultural norms and behaviors of European Americans and eschewing longstanding cultural buffering mechanisms may be maladaptive for members of this population. Yet, our results provide no statistically significant support for direct benefits of ethnic identity in this sample of low-SES African American women.

Despite the lack of evidence for a direct effect of ethnic resources, we did identify a moderating effect of ethnic affirmation. That is, the adverse impact of gendered racism experiences was substantially attenuated in the presence of strong, positive feelings about being African American. Feeling good about one’s ethnicity may be particularly effective in helping low-SES African American women externalize racist or sexist slights and humiliations, reducing the likelihood that these events will have a negative impact on self-concept. If a person has invested time and cognitive resources in strengthening a valued identity, occasional devaluation of that identity by others may have minimal effects. Moreover, possessing a sense of collective identity with other African Americans may lead to feelings of belonging and acceptance. These feelings may minimize the impact of racial and socioeconomic oppression, particularly if these negative experiences promote bonding and a common understanding among members of a disadvantaged group.

The Role of Self-Reported Skin Color

Perhaps the most interesting result to emerge from this research is the protective influence of self-reported skin color. Specifically, we found that among low-SES African American women who classified their skin tone as medium or dark, experiencing gendered racism substantially increased risk for suicidality, while there was no significant effect among those reporting light skin. Skin color has played a significant role in the life chances of African Americans since the American slave trade when the biracial offspring of European American masters were thought to be more intelligent and were afforded numerous privileges not available to their darker peers (Lake 2003; Russell et al. 1993). Research indicates that today, lighter skinned African Americans tend to have higher educational attainment, occupational prestige, and income and that the effects of skin tone on stratification outcomes exceed those of even parental SES (Keith and Thompson 2003). Moreover, light skin color may be particularly influential for African American women since whiteness is a critical aspect of the racialized feminine beauty ideal in the U.S. (Hunter 1998). Given the triple status disadvantage associated with being African American, female, and socioeconomically disadvantaged, having lighter and more European features may have an especially strong effect on the psychological well-being and life chances of these women.

Research suggests that because lighter skin is predictive of better stratification outcomes, having this physical trait may actually decrease the level of racism and sexism experienced by women (Hunter 1998). Klonoff and Landrine (2000) found that African Americans with dark skin were 11 times more likely to experience frequent racial discrimination than their lighter skinned counterparts. Patterns such as harsher sentencing in the criminal justice system and reduced likelihood of holding elected office (Hochschild and Weaver 2007) on the basis of colorism also reflect greater vulnerability to racism among those with dark skin. If African Americans with lighter skin women attain higher SES and are afforded increased prestige as a function of their attractiveness, they may be less likely to be in social roles and contexts (e.g., racially segregated neighborhoods, low-skill employment, single motherhood, etc.) that increase vulnerability to overt and institutionalized racist and sexist life events and stressors (Clark et al. 1999). Along the same lines, even if light skin does not actually reduce the vulnerability of low-SES African American women to gendered racism, it might cause them to be less sensitive to or perceptive of prejudice and discrimination (Klonoff and Landrine 2000). These processes may increase vulnerability of low-SES African American women reporting darker skin to suicidality or other adverse mental and physical health outcomes in the face of racism and other stressors.

Yet, results indicate that the women in this sample with self-reported light skin did not actually experience or perceive significantly lower levels of gendered racism events than those with medium or darker skin. Rather, while women with light skin reported experiencing similar levels of gendered racism events, these had no adverse effect on suicide risk in this group. Moreover, though it seems possible that the protective effects of light skin were actually confounded by ethnic affirmation (also identified as a buffering mechanism in our sample), findings disconfirm this explanation, as well. In fact, individuals with self-reported medium-to-dark skin had significantly higher levels of positive feelings toward their ethnic group and ethnic identity achievement relative to those with light skin. In other words, it is not the case that the increased vulnerability of women with medium-to-dark skin to the adverse effects of gendered racism can be explained by negative feelings about being African American or weaker commitment to the African American ethnic identity, both of which were protective resources.

In light of these results, a potential explanation for the moderating effects of self-reported light skin color relates to differential levels of distress in response to gendered racism. This may occur for two reasons. First, coping with multiple status disadvantages may lead to increased sensitivity to the adverse psychological effects of race and gender-based prejudice and discrimination, particularly in this low-SES sample (Thompson and Keith 2001). Existing research suggest that African American women are more likely to experience psychological distress in response to sexism (Klonoff and Landrine 1995; Landrine et al. 1995) and racism (Greer et al. 2009; Moradi and Subich 2003) than either European American women or African American men. Thus, it is possible that low-SES women with darker skin, who do not enjoy the status benefits conferred to African American women with more European features, are more likely to internalize prejudice, humiliation, and traumatic events related to racial or gender oppression. Indeed, research suggests that African Americans with lighter skin receive preferential treatment even within their own families and communities—social contexts in which African American women have traditionally sought affirmation—leaving those of darker complexion with feelings of low self-esteem (Thompson and Keith 2001, 2004). Internalized racism or preference for whiteness does not imply weakness or inadequacies on the part of disadvantaged groups or individuals. Rather, it is an inevitable response to systematic oppression and one tool through which dominant groups justify and maintain their privilege (Pyke 2010).

Second, a stronger stress response among women with self-reported medium-to-dark skin may relate to differences in strength of racial identity achievement in the current sample. Hochschild and Weaver (2007) note that individuals with a strong racial identity “look at the world through a racial lens” and “invoke a racial connotation in interpreting complex situations and subtle interpersonal cues” (p. 13). Because lighter and darker-skinned African Americans share a similar fate in relation to European Americans and a history of racial oppression, they are equally likely to perceive gendered racism. Yet, if race holds a higher place in the identity hierarchies of low-SES African American women with darker skin, threats to a positive racial identity may be more distressing. Ultimately, in-depth qualitative or social psychological research is needed to adjudicate between potential explanations and provide a more nuanced understanding of the role of skin color in the stress process.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has several notable limitations. First, the measures of suicidality, mental health status, and substance abuse status were dichotomous, prohibiting a more fine-grained examination of severity. However, alternative coding and measures did not alter results. In addition, these data examine the effects of negative life events attributed to gendered racism, but to not adequately capture microaggressions. Future research should examine these more subtle and ambiguous experiences of racism and sexism. Also, the measure of skin color was self-reported and may not have reflected actual skin color. However, a woman’s perception of her own skin color is likely to be more a powerful predictor of feelings of self-worth, stress response, and other social psychological processes than an external evaluation. Nonetheless, future research should explore whether the moderating effect of self-reported skin color holds for more objective measures.

Also, the data used here were not based on a nationally representative sample of African American women. Specifically, marriage rates, percent college educated, and household income were lower than national averages for African American women based on census reports. These differences were likely a result of sampling largely in racially and socioeconomically segregated neighborhoods with a high proportion of African Americans. In addition, because the community sample was drawn to make comparisons to a sample of women in prison, a disproportionate percentage of respondents were illicit drug users. It is important to note that controlling for income, education, marital status, and drug use did not change the substantive findings. However, readers should use caution when interpreting results and be aware that findings cannot be extended to African American women in higher socioeconomic strata.

In addition, because this research was cross-sectional, the directionality of effects could not be determined. Women exhibiting suicidal ideation and behavior probably have a more pessimistic outlook than those with better mental health, increasing their likelihood of perceiving racism and sexism in interpersonal interactions and negative life events. Similarly, factors potentially correlated with suicidality—including low self-esteem and perceived control—might have affected reactions to gendered racism among women in the sample (Clark et al. 1999). Given these methodological limitations, a key contribution of this study is to serve as a starting point for more in-depth, longitudinal, nationally representative research on suicide in African American women. Future research should work to identify the complex pathways linking suicide and related mental health outcomes to social status, structural constraints and vulnerabilities, experiences of institutional and interpersonal racism and sexism, and cultural protective factors specific to particular ethnic groups.

Despite these limitations, this research makes several important contributions, examining cultural risk and protective factors for suicidality among low-SES African American women (Walker 2007). While research on the mental health consequences of racism is not new, this analysis adds gender and SES components and also extends this literature to suicide—a topic rarely investigated in samples of African American women. Moreover, this analysis moves beyond simply documenting gender and racial mental health disparities, exploring the moderating effects of ethnic identity and skin color. We found evidence for the proposed conceptual model (See Fig. 1), lending support to the importance of the match between moderators and stressors. These findings are compelling and suggest a need to better understand the role of colorism in coping with racism and sexism and in the identities of low-SES African American women.

Finally, our findings have significant public health implications. They contribute to the knowledge of antecedents of suicide among African American women who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, facilitating the development of more effective, culturally specific interventions for this population. Also, our research suggests that low-SES women with darker skin who are vulnerable to racism and sexism may be at high risk for suicidal ideation or attempt. These findings are important for practitioners in their assessment of suicide risk and prevention of suicide in this group.

Notes

Analyses were conducted separately for suicidal ideation and behavior. Results for suicidal behavior were in the same direction as findings for the combined measure, but did not consistently achieve statistical significance. Using the combined measure provides better model fit as suggested by the Bayesian Information Criterion and likelihood ratio Chi-square test. Findings for suicidal ideation mirrored those for the combined measure, with estimates and standard errors that consistently achieved significance. Full results are available upon request.

Only about one-third of the sample used drugs in the past month, and the majority of activity reported was occasional marijuana use as opposed to use of other “hard” drugs.

Though socioeconomic-, mental health-, and substance abuse status could all justifiably serve as moderators in the relationship between gendered racism and suicidal ideation and behavior, these interactions were not statistically significant.

Though skin color and ethnic resources were significantly associated, the degree of variation between these measures and the regression results presented below suggested that they are conceptually distinct.

References

Agerbo, E., Nordentoft, M., & Mortensen, P. B. (2002). Familial, psychiatric, and socioeconomic risk factors for suicide in young people: Nested case-control study. British Medical Journal, 325, 1–5.

Agerbo, E., Qin, P., & Mortensen, P. B. (2006). Psychiatric illness, socioeconomic status, and marital status in people committing suicide: A matched case-sibling-control study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 776–781.

Anderson, L. P. (1991). Acculturative stress: A Theory of relevance to Black Americans. Clinical Psychology Review, 11, 685–702.

Aneshensel, C. S., Rutter, C. M., & Lachenbruch, P. A. (1991). Social structure, stress, and mental health: Competing conceptual and analytic models. American Sociological Review, 56, 166–178.

Beale, F. (1995). Double jeopardy: To be black and female. In B. Guy-Sheftall (Ed.), Words of fire: An anthology of African American feminist thought. New York, NY: New Press.

Bodenhorn, H. (2006). Colorism, complexion homogamy, and household wealth: Some historical evidence. American Economic Review, 96, 256–260.

Bond, S., & Cash, T. F. (1992). Black beauty: Skin color and body images among African-American college women. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22, 874–888.

Brown, D. R. (2003). A conceptual model of mental well-being for African American women. In D. R. Brown & V. M. Keith (Eds.), In and out of our right minds (pp. 1–19). New York: Columbia University Press.

Bryant-Davis, T. (2005). Racist incident-based trauma. The Counseling Psychologist, 33, 479–500.

Buchanan, N. T., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2008). Effects of racial and sexual harassment on work and the psychological well-being of African American women. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13, 137–151.

Center for Disease Control; CDC. (2011). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system, 1981–1998. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans. American Psychologist, 54, 805–816.

Conwell, Y., Dubertstein, P. R., & Caine, E. D. (2002). Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 193–204.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). Souls of black folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg.

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Chapman, D. P., Williamson, D. F., & Giles, W. H. (2001). Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span. Journal of the American Medical Association, 307, 883–885.

Evans, E., Hawton, K., & Rodham, K. (2004). Factors associated with suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 957–979.

Feagin, J. R. (1991). The continuing significance of race: Antiblack discrimination in public places. American Sociological Review, 56, 101–116.

Feagin, J. R. (2001). Racist America. Roots, current realities, & future reparations. New York NY: Routedge.

Feskanich, D., Hastrup, J. L., Marshall, J. R., Colditz, G. A., Stampfer, M. J., Willett, W. C., et al. (2002). Stress and suicide in the Nurses’ Health Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 95–98.

Foreman, T. A., Williams, D. R., & Jackson, J. S. (1997). Race, place, and discrimination. Perspectives on Social Problems, 9, 231–261.

Franklin, A. J., Boyd-Franklin, N., & Kelly, S. (2006). Racism and invisibility: Race-related stress, emotional abuse and psychological trauma for people of color. In L. V. Blitz & M. P. Greene (Eds.), Racism and racial identity: Reflections on urban practice in mental health and social services. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Ghavami, N., Fingerhut, A., Peplau, L., Grant, S. K., & Wittig, M. A. (2011). Testing a model of minority identity achievement, identity affirmation, and psychological well-being among ethnic minority and sexual minority individuals. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 79–88.

Gibbs, J. T. (1997). African American suicide: A cultural paradox. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 27, 68–79.

Greer, T. M., Laseter, A., & Asiamah, D. (2009). Gender as a moderator of the relation between race-related stress and mental health symptoms for African Americans. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 295–307.

Harrell, S. P. (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of People of Color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 42–57.

Hersch, J. (2006). Skin tone effects among African Americans: Perceptions and reality. The American Economic Review, 96, 251–255.

Hochschild, J. L., & Weaver, V. (2007). The skin color paradox and the American racial order. Social Forces, 86, 643–670.

Hooks, B., & Mesa-Bains, A. (2006). Homegrown: Engaged cultural criticism. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Hunter, M. (1998). Colorstruck: Skin color stratification in the lives of African American women. Sociological Inquiry, 68, 517–535.

Iwamoto, D. K., & Liu, M. W. (2010). The impact of racial identity, ethnic identity, Asian values, and race-related stress on Asian Americans and Asian international college students’ psychological well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 79–91.

Jackson, F. M. (2002). Considerations for community-based research with African American women. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 561–564.

Jackson, J. S., Brown, T. N., Williams, D. R., Torres, M., Sellers, S. L., & Brown, K. (1996). Racism and the physical and mental health status of African Americans: A thirteen year national panel study. Ethnicity and Disease, 6, 132–147.

Jackson, F. M., Hogue, C. R., & Phillips, M. T. (2005). The development of a race and gender-specific stress measure for African-American women: Jackson, Hogue, Phillips contextualized stress measure. Ethnicity and Disease, 15, 594–600.

Joe, S., Baser, R. E., Breeden, G., Neighbors, H. W., & Jackson, J. S. (2006). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among Blacks in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 296, 2112–2123.

Jones, C., & Shorter-Gooden, K. (2003). Shifting: The double lives of black women in America. New York: Harper Collins.

Keith, V., & Herring, C. (1991). Skin tone and stratification in the black community. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 760–778.

Keith, V. M., & Thompson, M. S. (2003). Color matters: the importance of skin tone for African American women’s self-concept in Black and White America. In D. R. Brown & V. M. Keith (Eds.), In and out of our right minds. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kessler, R. C., Mickelson, K. D., & Williams, D. R. (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 208–230.

Kessler, R. C., Borges, G., & Walters, E. E. (2001). Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 617–626.

King, K. R. (2003). Racism or sexism? Attributional ambiguity and simultaneous membership in multiple oppressed groups. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 223–247.

Klonoff, E., & Landrine, H. (1995). The schedule of sexist events: A measure of lifetime and recent sexist discrimination in women’s lives. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 439–472.

Klonoff, E., & Landrine, H. (1999). Cross-validation of the Schedule of Racist Events. Journal of Black Psychology, 25, 231–254.

Klonoff, E., & Landrine, H. (2000). Is skin color a marker for racial discrimination?: Explaining the skin color-hypertension relationship. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23, 329–338.

Krieger, N. (1990). Racial and gender discrimination: Risk factors for high blood pressure? Social Science and Medicine, 30, 1273–1281.

Lake, O. (2003). Blue veins and Kinky hair: Naming and color consciousness in African America. Westport, CT: Kraeger.

Landrine, H., & Klonoff, E. (1996). The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22, 144–168.

Landrine, H., Klonoff, E., Gibbs, J., Manning, V., & Lund, M. (1995). Physical and psychiatric correlates of gender discrimination: An application of the Schedule of Sexist Events. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 473–492.

Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. New York: Springer.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Maddox, K. B. (2004). Perspectives on racial phenotypicality bias. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 383–401.

Maris, R. W. (1997). Social and familial risk factors in suicidal behavior. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20, 519–550.

Massey, D. (2004). Segregation and stratification: A biosocial perspective. The DuBois Review, 1, 7–25.

Moradi, B., & Subich, L. M. (2003). A concomitant examination of the relations of perceived racist and sexist events to psychological distress for African American women. The Counseling Psychologist, 31, 451–469.

Morrison, R., & O’Connor, R. (2005). Predicting psychological distress in college students: The role of rumination and stress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 447–460.

Moscicki, E. K. (1997). Identification of suicide risk factors using epidemiologic studies. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20, 499–517.

Moscicki, E. K. (2001). Epidemiology of completed and attempted suicide: Toward a framework for prevention. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 1, 310–323.

Outten, H. R., Schmitt, M. T., Garcia, D. M., & Branscombe, N. R. (2009). Coping options: Missing links between minority group identification and psychological well-being. Applied Psychology, 58, 146–170.

Patton, T. O. (2006). Hey girl, am I more than my hair?: African American women and their struggles with beauty, body image, and hair. Feminist Formations, 18, 24–51.

Pearlin, L. I. (1999). Stress and mental health: A conceptual overview. In A. V. Horwitz & T. L. Scheid (Eds.), A handbook for the study of mental health (pp. 161–175). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Perry, B. L., Pullen, E., & Oser, C. B. (2012). Too much of a good thing? Psychosocial resources, gendered racism, and suicidal ideation among low-socioeconomic status African American women. Social Psychology Quarterly. doi:10.1177/0190272512455932

Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., & Tehranifar, P. (2010). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, S28–S40.

Phinney, J. S. (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A New Scale for Use with Diverse Groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176.

Phinney, J., & Ong, A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281.

Poussaint, A. F., & Alexander, A. (2000). Lay my burden down: Suicide and the mental health crisis among African-Americans. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Pyke, K. D. (2010). What is internalized racial oppression and why don’t we study it? Acknowledging racism’s hidden injuries. Sociological Perspectives, 53, 551–572.

Rogers Wood, N. A., & Petrie, T. A. (2010). Body dissatisfaction, ethnic identity, and disordered eating among African American women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 141–153.

Russell, K., Wilson, M., & Hall, R. (1993). The color complex: The politics of skin color among African Americans. New York: Anchor Books.

Saltzberg, E. A., & Chrisler, J. C. (1997). Beauty is the beast: Psychological effects of the pursuit of the perfect female body. In D.Estelle (Ed.), Reconstructing gender: A multicultural anthology (pp. 134–145). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing.

Sanchez-Hycles, J. V. (1999). Racism: Emotional abusiveness and psychological trauma for ethnic minorities. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 1, 69–87.

Scott, L. D. (2003). The relation of racial identity and racial socialization to coping with discrimination among African American adolescents. Journal of Black Studies, 33, 520–538.

Sellers, R. M., Caldwell, C. H., Schmeelk-Cone, K. H., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2003). Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 302–317.

Sellers, R. M., Copeland-Linder, N., Martin, P. P., & Lewis, R. L. (2006). Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 187–216.

Sigelman, L., & Welch, S. (1991). Black Americans’ views of racial inequality: The dream deferred. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Spicer, R. S., & Miller, T. R. (2000). Suicide acts in eight states: Incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 1885–1891.

Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Sue, D. W., Nadal, K., Capodilupo, C., Lin, A., Torino, G., & Rivera, D. (2008). Racial microaggressions against Black Americans: Implications for counseling. Journal of Counseling and Development, 86, 330–338.

Szymanski, D., & Stewart, D. (2010). Racism and sexism as correlates of African American women’s psychological distress. Sex Roles, 63, 226–238.

Thomas, A. J., Witherspoon, K. M., & Speight, S. L. (2008). Gendered racism, psychological distress, and coping styles of African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 307–314.

Thomas, A. J., Hacker, J. D., & Hoxha, D. (2011). Gendered racial identity of Black young women. Sex Roles, 64, 530–542.

Thompson, M. S., & Keith, V. M. (2001). The blacker the berry: Gender, skin tone, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. Gender & Society, 15, 336–357.

Thompson, M. S., & Keith, V. M. (2004). Copper brown and blue black: Colorism and self-evaluation. In C. Herring, V. M. Keith, & H. W. Horton (Eds.), Skin deep: How race and complexion matter in the “color-blind”. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Utsey, S. O., & Hook, J. N. (2007). Heart rate variability as a physiological moderator of the relationship between race-related stress and psychological distress in African Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 13, 250–253.

Utsey, S. O., Giesbrecht, N., Hook, J., & Stanard, P. M. (2008). Cultural, sociofamilial, and psychological resources that inhibit psychological distress in African Americans exposed to stressful life events and race-related stress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 49–62.

Verkuyten, M. (2010). Assimilation ideology and situational well-being among ethnic minority members. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 269–275.

Wallace, S. A., Townsend, T. G., Glasgoq, Y. M., & Ojie, M. J. (2011). Gold diggers, video vixens, and jezebels: Stereotype images and substance use among urban African American girls. Journal of Women's Health, 20, 1315–1324.

Walker, R. L. (2007). Acculturation and acculturative stress as indicators for suicide risk among African Americans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 386–391.

Walker, R. L., Wingate, L. R., Obasi, E. M., & Joiner, T. E. (2008). An empirical investigation of acculturative stress and ethnic identity as moderators for depression and suicidal ideation in college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 75–82.

Wethington, E., McLeod, J., & Kessler, R. C. (1987). The importance of life events for explaining sex differences in psychological distress. In R. C. Barnett, L. Biener, & B. K. Baruch (Eds.), Gender and stress (pp. 144–154). New York: Free Press.

Williams, D. R., & Williams-Morris, R. (2000). Racism and mental health: The African American experience. Ethnicity and Health, 5, 243–268.

Woods-Giscombe, C. L., & Lobel, M. (2008). Race and gender matter: A multidimensional approach to conceptualizing and measuring stress in African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 173–182.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA22967).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perry, B.L., Stevens-Watkins, D. & Oser, C.B. The Moderating Effects of Skin Color and Ethnic Identity Affirmation on Suicide Risk among Low-SES African American Women. Race Soc Probl 5, 1–14 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-012-9080-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-012-9080-8