Abstract

Life-course transitions are important drivers of mobility, resulting in a concentration of migration at young adult ages. While there is increasing evidence of cross-national variations in the ages at which young adults move, the relative importance of various key life-course transitions in shaping these differences remains poorly understood. Prior studies typically focus on a single country and examine the influence of a single transition on migration, independently from other life-course events. To better understand the determinants of cross-national variations in migration ages, this paper analyses for Australia and Great Britain the joint influence of five key life-course transitions on migration: (1) higher education entry, (2) labour force entry, (3) partnering, (4) marriage and (5) family formation. We first characterise the age profile of short- and long-distance migration and the age profile of life-course transitions. We then use event-history analysis to establish the relative importance of each life-course transitions on migration. Our results show that the age structure and the relative importance of life-course transitions vary across countries, shaping differences in migration age patterns. In Great Britain, the strong association of migration with multiple transitions explains the concentration of migration at young adult ages, which is further amplified by the age-concentration and alignment of multiple transitions at similar ages. By contrast in Australia a weaker influence of life-course transitions on migration, combined with a dispersion of entry into higher education across a wide age range, contribute to a protracted migration age profile. Comparison by distance moved reveals further differences in the mix of transitions driving migration in each country, confirming the impact of the life-course in shaping migration age patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Migration is an age-selective process, young adults being the most mobile group. The propensity to migrate typically peaks at young adult ages and then steadily declines with increasing age (Rogers and Castro 1981). Underpinning these regularities is a collection of life-course transitions, such as entry to the labour force and partnership formation, which often trigger a change of residence (Mulder 1993; Warnes 1992a). While there is a large body of literature that examines the age variation in migration streams between regions within individual countries (Bracken and Bates 1983; Plane and Heins 2003; Rogers and Castro 1981), it is only recently that comparative studies have revealed systematic variations between countries in the aggregate age profile of migration. In particular, internal migration in Asia is strongly concentrated in the early twenties, whereas in Europe and North America migration peaks at older ages and is spread across a wider age range (Bell and Muhidin 2009). At the same time, there are differences in migration ages among countries at similar levels of development (Ishikawa 2001), and among countries within the same region (Bernard et al. 2014a; Kawabe 1990).

In an early attempt to compare migration age patterns between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, Warnes (1992b) suggested that differences in the timing of life-course transitions underpin cross-national variations in migration age patterns, but he did not empirically tested this proposition. Drawing on this early work, recent studies have endeavoured to explain variations in migration ages by examining the association between the age structure of migration and that of the life-course. Bernard et al. (2014b) compared 27 countries with diverse migration age patterns and showed that the age profile of migration broadly mirrors the age-structure of key transitions. Another line of enquiry has attempted to identify differences in the extent to which particular life-course transitions are connected with mobility choices. Mulder and Clark (2002) compared the link between entry into higher education and departure from the parental home in Germany, the Netherlands and the United States. Similarly, Mulder and Wagner (1998) examined the move to first home ownership and its association with marriage and childbirth in Germany and the Netherlands. While this work suggests that particular transitions differ in their influence on mobility, it has yet to establish the relative importance of a series of key life-course events in shaping migration age profiles in different countries. The extent to which the influence of particular transitions varies with the distance moved, and in turn contributes to variations in migration ages, also remains to be established.

This paper seeks to address these deficiencies by measuring the joint impact of the five key life-course transitions to adulthood, and establishing their relative influence on migration. We adopt a comparative perspective, contrasting Great Britain and Australia. Using closely comparable datasets, we explore how the influence of life-course transitions on migration differs between countries, and link these to the broader socio-economic context. We focus on aggregate migration, which captures all moves between regions within a country, as the most appropriate basis for cross-national comparisons (Bell et al. 2002).

To these ends, we adopt a proximate determinants framework adapted from the fertility literature (Bongaarts 1978), which situates life-course transitions as intermediaries between the broader socio-economic context and migration outcomes. We further extend the existing literature by differentiating between short- and long-distance migration, the ultimate aim being to enhance understanding of cross-national variations in migration age patterns. This work forms part of a project (author identifying reference), an international collaborative program of research, which aims to develop and implement a set of rigorous statistical indicators of internal migration that can be used to make comparisons between countries across several dimensions, including age, and explain cross-national variations.

To establish the association between the age patterns of migration and those of life-course transitions, we first characterise the age profile of migration and the age profile of five key transitions that are concentrated at young adult ages and effectively mark the passage to adulthood: higher education entry, labour force entry, cohabitation, marriage and first child bearing. We consider two forms of union formation separately because cohabitation often serves either as an alternative to or as a prelude to marriage in most industrialised nations (Heuveline and Timberlake 2004) and because the timing of these two transitions differ (Baxter and Evans 2013). We then use event-history analysis to establish the relative importance of these transitions in shaping short- and long-distance migration age profiles in each country. Finally, we link the significance of specific transitions to migration within each country to cross-national variations in migration ages.

The paper is organised as follows. Section “Theoretical background” presents the conceptual framework linking migration age patterns to life-course transitions and contextual factors. The third section describes the panel “Data and the methods” used. The fourth section examines the “Age distribution of migration and of life-course events” as a first step in understanding the linkages between the age structure of migration and that of the life-course. Section “Migration and life-course events: What is the link?” reports the results of the event-history analysis, and explains how differences in the relative importance of particular transitions contribute to variations in migration age patterns. Section “Socio-economic context: What influence?” discusses the influence of contextual factors on the life-course, and hence mobility. In last section concludes with recommendations for future comparative research.

Theoretical background

The propensity to move varies markedly across the life-course (Rogers and Castro 1981). As shown in Fig. 1, migration intensity typically peaks in the young adult years as this age span contains critical life-course transitions (Rindfuss 1991). Five such transitions typically recognised are entering higher education, taking up a first employment, entering a union, getting married, and forming a family, all of which may trigger individuals to move (Mulder 1993). As such, geographic mobility itself marks an important stage in the transition to adulthood and independence, bringing with it the opportunity to construct a new identity, free from family ties and connections to the home space (Giddens 1991).

For many young adults, the move away from home to pursue further education is the first step in the transition to independent living (Mulder and Clark 2002). Such moves are common in many industrialised nations as prospective students select higher education institutions according to suitability, reputation (Faggian et al. 2007; McCann and Sheppard 2001) and accessibility (Bornholt et al. 2004; Hoare 1991; James et al. 1999). After graduation, students capitalise on their investment in human capital and either stay in their region of study, move elsewhere, or return to their parental home (Venhorst et al. 2011). The propensity to move is especially high immediately after graduation (Corcoran et al. 2010; Dotti et al. 2013; Faggian et al. 2013; Haapanen and Tervo 2009), as students maximise employment opportunities.

Union formation also plays a central role in shaping the life-course and driving mobility (Courgeau 1985; Flowerdew and Al-Hamad 2004; Mulder and Wagner 1993), particularly over short-distances. On forming a co-residential union, at least one of the partners has to move to establish a new household, although it is not uncommon that both partners move to a new joint home (Manning and Smock 2005). Evidence from the United Kingdom suggests that 80 % of individuals change residence within a year of forming a partnership (Flowerdew and Al-Hamad 2004; Grundy 1992). Subsequently, the birth of a first child often leads to a change of residence to accommodate new housing needs (Clark and Huang 2003). In some instances, family formation can trigger long-distance migration (Kulu 2008; Lindgren 2003).

Building on evidence that certain life-course transitions are instrumental in generating moves (Mulder 1993; Warnes 1992a) and that variations in the structure of the life-course are attributable to the combined effect of institutional arragements, social welfare policies, cultural heritage and economic conditions (Buchmann and Kriesi 2011), Bernard et al. (2014b) proposed a conceptual framework according to which contextual factors shape the structure and timing of life-course transitions, which in turn determine migration age patterns. Adapted from Bongaarts’ model of proximate determinants of fertility (1978), this framework suggests that life-course transitions act as intermediaries between contextual factors and migration, and they are therefore referred to as proximate determinants. Shifts in relative cohort size, recessionary periods or increases in educational participation exert indirect effects on migration ages by altering the timing of various life-course transitions that are linked to migration. For instance, the establishment of compulsory education and the progressive extension of education to older ages during the twentieth century restructured the transition to adulthood in Europe by extending childhood dependency and labour force entry to later in life, leading to a shift in the age profile of migration to older ages (Warnes 1992b). In a similar manner, mobility among young adults is delayed and its intensity diminished for larger cohorts (Milne 1993; Pandit 1997) because of increased competition for employment and housing opportunities among young adults, which in turn delays labour force entry and family formation (Jeon and Shields 2005). Similarly, recessionary periods may act indirectly by postponing entry into the labour force (Easterlin et al. 1978) and delaying new household formation (Sobotka et al. 2011). Application of this framework to 27 countries with diverse migration age patterns showed that the age profile of migration broadly mirrors the age-structure of the life-course (Bernard et al. 2014b).

Such studies, however, are descriptive; they explored these links by comparing measures of the timing and spread of transitions to the age and intensity at peak migration, but did not consider the relative influence of each life-course transition on migration. Greater attention is therefore needed to the relation between migration and the life-course transitions that accompany the transition to adulthood to identify differences in the extent to which particular transitions are connected with migration and how these variations, in turn, contribute to cross-national differences in migration age patterns. To address this gap, we apply the proximate determinants framework proposed by Bernard et al. (2014b) and use event-history analysis to quantitatively link life-course transitions to migration in Australia and Great Britain in order to establish the extent to which the relative importance of life-course transitions on migration varies between countries. Because the young adult years correspond to the period of the life course during which the majority of moves take place (Rogers and Castro 1981) and during which cross-national differences in migration are concentrated (Bell and Muhidin 2009; Bernard et al. 2014a), we focus on the five transitions shown to be key markers in the transition to adulthood (Gauthier 2007) and important triggers of spatial mobility (Mulder 1993): higher education entry, labour force entry, union formation, marriage and first childbearing (Fig. 2).

The Proximate Determinants of Migration Age Patterns. Source: Bernard et al. (2014b)

Data and methods

Longitudinal datasets

To establish the relationship between migration and life-course events, we use nationally-representative annual longitudinal household surveys from the two countries, the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, conducted since 2001, and the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), run since 1991. Comparing Australia and Great Britain brings the particular advantage that the BHPS and the HILDA survey have similar designs. Both include individuals living in boarding schools and university colleges, and record the place of residence of household members who are away from home, living in study-related accommodation (Watson and Wooden 2002), thereby capturing moves for educational purposes. Each survey collects the respondent’s place of usual residence at successive waves by tracking households who moved to a different location and individuals who left their original household. They also report the respondent’s educational, employment, marital and parental status at each wave. At the time of the analysis, a total of 9 waves were available for Australia and 17 for Great Britain.

We define migration as a change of usual place of residence between two consecutive waves, which corresponds to an interval of about a year. Each survey reports place of residence based on different administrative units: states in Australia and government office regions in Great Britain. Differences in the number and shape of geographic zones is commonly recognised as the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) (Wrigley et al. 1996). This is particularly problematic for cross-national comparisons as zonal systems vary across countries, making it difficult to compare spatial units across countries (Bell et al. 2002). To minimise the effect of differences in these spatial frameworks, we measure migration as a change of residence, irrespective of whether it occurs within or between administrative units, and denote this measure ‘all moves’. This is the closest possible approximation we can get to the all-changes-of-address measure, which is the most consistently reliable gauge of migration between countries (Bell et al. 2015). In Australia, this captures all changes of statistical division of residence, within or between states, and in Great Britain it measures all changes of local authority, within and between government office regions. Despite differences in land area and settlement patterns, migration intensities in the two countries are similar at this level of spatial scale. In Australia, 6.9 % of young adults aged 17–35 changed statistical division of residence within a year, while in Great Britain 7.9 % changed local authority of residence. To take into account the fact that reasons for moving vary with distance (Baccaïni and Courgeau 1996; Bogue et al. 2009; Long 1988; Niedomysl 2011), we also conduct the analysis distinguishing between long- and short-distance migration. A move between major spatial units (e.g. states in Australia) is classified as long-distance migration, whereas a move between minor spatial units (e.g. statistical division within a state in Australia) is classified as short-distance migration. Table 1 summarises the spatial framework used for each country.

A total of 5718 individuals aged 17–35 were interviewed in the first wave of HILDA, of which 48.6 % completed all 9 waves, which corresponds to an average annual attrition of 8.5 %. This level is in line with other longitudinal surveys such as the Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth (LSAY), which recorded a retention rate of 44.8 % over 8 annual waves (Rothman 2009). However, as many as 85.8 % of individuals in the original sample were interviewed in at least two consecutive survey waves and are therefore included in the analysis. In Great Britain, of the 3744 individuals aged 17–35 interviewed at the first wave of the BHPS, 58.5 % completed the first 9 waves and 44.4 % completed all 17 waves.

Rates of attrition are known to be higher among migrants than non-migrants (Alderman et al. 2001), thus some moves are inevitably missed. However, a number of recent studies that have examined the association between migration and key life-course events in the British and Australia contexts have assessed that attrition does not bias the analysis of geographic mobility when using data from the BHPS (Buck 2000; Rabe and Taylor 2010) and HILDA (Sander and Bell 2014). The addition of a binary indicator of attrition and interaction terms between the attrition dummy and all other explanatory variables in regression analysis of migration showed that predictors of both short- and long-distance moves do not differ between non-attrited and attrited households. Non-respondents are more likely to reside in high population density regions, where flat and multi-unit dwellings hinder survey participation (Groves and Couper 1998). While attrition has been shown to be higher in London and Sydney than other regions of Great Britain (Uhrig 2008) and Australia (Waston and Wooden 2004), the application of sample weights ensures that both samples remain geographically representative over time (Watson and Wooden 2009). In addition, the analysis of attrition within the PSID in the United States showed that, in a regression context, attrition is likely to affect the intercept terms but has relatively little effect on the slopes of key coefficients (Fitzgerald et al. 1998).

Analytical strategy

We use event-history analysis to quantify the relative importance of each life-course transition on migration and restrict the analysis to individuals who were aged between 17 and 35 in at least one of the waves, which corresponds to the period of life where the transitions of interest typically occur. We do not consider departure from the parental home as it is commonly associated with other transitions such as higher education entry, labour market entry and union formation (Mulder et al. 2002; Patiniotis and Holdsworth 2005; Yi et al. 1994). We define a life-course transition as a change in status between two consecutive survey waves, which corresponds to about a 1-year interval. Entry into some statuses, such as being in the labour force, does not preclude subsequent exit (Shanahan 2000). While some transitions are reversible, the transition into a status never previously held incurs obligations that are generally lasting, making a first status change a “binding transition” (Modell et al. 1976). For instance, the first commitment to regular work imposes long-lasting obligations and creates self-binding commitments, such as financial independence, that are not easily reversible. Getting married or becoming a parent also incur permanent obligations and enduring relationships despite the reversible nature of marriage. Hence, we define life-course transitions as the first transition into a status never held before (e.g. first entry into the labour force and first union formation), and disregard subsequent events of a similar type.

As noted above, migration and life-course transitions are defined as discrete events: a change of residence between two waves and a change of status between two waves. We have therefore pooled observations across waves to perform a discrete-time event-history analysis based on person-wave data, in which individual characteristics are recorded at each wave, and model the probability of a transition associated with a change of residence in the same year. When different transitions occur within the same year, which is the case for less than 20 % of all transitions recorded in both countries, they are allocated equal probabilities. We use a logistic regression framework to establish the association between migration and individual characteristics (Mulder and Wagner 1998, 2001; Reed et al. 2010). This model provides a satisfactory approximation for continuous-time models (Allison 1982; Yamaguchi 1991) and allows for time-varying independent variables, with covariates being measured at each discrete time-interval (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004), a feature particularly useful for examining the determinants of migration. In a logistic regression model framework, the predicted probability of moving p by individual i in year t is specified as follows (Gujarati and Porter 2009):

where Xit = (X1it,…,XKit) is a time-varying covariate vector, Zi = (Z1i,…,ZLi) is a time-constant covariate vector, βk = (βi,…, βK) and γl = (γ1,…, γL) are the respective coefficients, and α is the constant term. Time-varying covariates include life-course transitions: higher education entry, labour market entry, union formation and first childbearing. Drawing on previous studies, we have selected a set of individual-level control variables shown to exert an influence on mobility choices (Borjas 1994; Sjaastad 1962). Among the independent variables are measures of sex, age, age squared (to account for the non-linear effect of age), educational attainment (primary, secondary and tertiary), log of income, household status (being the head or the spouse of the head of the household or not), housing tenure (renting versus owning), place of birth (domestic versus overseas) and birth cohort. All these variables are time-varying and therefore updated at each time unit, with the exception of sex, place of birth and birth cohort, which are time-constant. We also control for survey wave and region of residence,Footnote 1 and include a measure of remoteness for Australia.Footnote 2 To take into account potential differences between males and females, we also run separate regressions for males and females. Survey respondents were not sampled independently, but from within households. Correlated observations violate standard assumptions of independence in statistical analysis, resulting in understated standard errors. We correct for the clustering of young adults within households using Huber-corrected standard errors based on the clustered sandwich estimator (Eicker 1967; Huber 1967).

Age distribution of migration and life-course events

We first examine the age profile of migration by plotting the proportion of individuals who moved at each single year of age. Migration intensities were normalised to sum to unity across all ages so that the comparison of age profiles would be independent of variations in overall migration levels. Figure 3 shows that in both countries the shape of the curve follows the general age pattern of migration (Rogers and Castro 1981), characterised by a peak at young adult ages, followed by a decline in the propensity to migrate thereafter. While migration peaks at 23 in both countries, in Great Britain migration activity is concentrated within a narrower age range. In Great Britain 75 % of moves occur between the ages of 17–35, compared to 60 % in Australia.

Normalised Age profiles of migration. Note: Authors’ calculations based on one-year interval migration data reported by single-year age groups. Migration data was normalised to sum to unity and smoothed using kernel regression (Bernard and Bell 2015)

Comparison of migration age patterns by distance moved reveals more pronounced differences between Great Britain and Australia. Figure 3 shows that migration over both short and long distances is concentrated within a narrower age range in Great Britain. These differences are especially visible for long-distance migration, with a stronger concentration of mobility at young adult ages in Great Britain than in Australia. Migration intensity declines sharply in the mid-twenties in Great Britain, but remains at a relatively high level until age 40 in Australia. With regard to timing, long-distance migration peaks at a younger age in Great Britain (20) than in Australia (24), but the opposite is true is for short-distance migration, which peaks at 21 in Australia and 24 in Great Britain. Migration age profiles by sex (see “Appendix 1”) show only minimal differences between men and women in both countries.

To identify the extent to which variations in migration age patterns reflect differences in the age structure of the life-course, we next plot the proportion of individuals who underwent a particular transition at each single year of age. These transition rates were normalised to sum to unity so that the comparison of age profiles would be independent of variations in the overall incidence of transitions. The age distribution of these transitions rates, as shown in Fig. 4, provides an indication of timing, i.e. how early or late in life individuals experience particular transitions within a country. We compute from those data the median age at which each transition occurs. To gauge the extent to which transitions within a population are concentrated within a narrow age range or spread more widely, we also plot the cumulative proportion of the population who completed a transition by single year of age. To gauge the spread of life-course transitions, we compute the interquartile range measured as the difference between the ages at which 25 and 75 % of the population have completed a particular transition. Median ages and interquartile ranges are reported in Fig. 4.

Normalised transition rates by age. Note: Authors’ calculations based on one-year interval migration data reported by single-year age groups. Migration data was normalised to sum to unity and smoothed using kernel regression. The x-axis represents single years of age and the y-axis represents the proportion of individuals who completed a transition

It is apparent that Australia and Great Britain share a number of common patterns, including a concentration of status changes at young age adult ages. For instance, the median age at entry into higher education is 19 years in both countries, and more than half the transitions to higher education occur between 17 and 20 in Australia and Great Britain. Comparison of median ages suggests a similar progression to other aspects of adult roles, starting with the passage from education to the labour market in the early twenties, followed by union and family formation in the mid to late-twenties. In both countries, less than 20 % of all transitions occur within the same year. In Australia, simultaneous transitions are mainly entry into partnership and marriage (4.8 % of all transitions) and education and labour market entry (3.1 %). In Great Britain, union formation and first childbirth (6.7 %) are the most closely synchronised, followed by partnership and labour market entry (1.6 %).

Age distributions reveal, however, pronounced variations between Australia and Great Britain. As indicated by interquartile ranges, most transitions are spread within a wider age range in Australia, in particular entry into higher education. It takes 8 years for the central 50 % of Australian youths to enter higher education, which is double the age-spread of Great Britain. As a result, only 20 % of individuals enter higher education after age 20 in Great Britain, compared to 40 % in Australia. The age distribution of entry into the labour force mirrors these differences, with 60 % of young adults being economically active by 20 in Great Britain compared to 50 % in Australia. Hence, the median age at labour market entry is 22 in Australia, 2 years later than in Great Britain. While Australia and Great Britain exhibit union and family formation curves of broadly similar shapes, with median ages between 24 and 29, those transitions are slightly shifted to older ages in Australia.

Graphical examination of the age distribution of migration and life-course events suggests that migration age profiles align well with some life-course transitions, which are likely explanations for differences in the specific ages at which migration occurs within each country. In particular, the strong concentration of migration activity in the early twenties in Great Britain parallels a relatively early and concentrated transition to higher education. In Australia, the wider dispersion of most life-course transitions across the age spectrum is a likely explanation for its more protracted migration age profile. However, while some life-course transitions align well with migration age profiles, others do not. For example, marriage and first childbirth are protracted and relatively late transitions in Great Britain, despite its early and concentrated migration age profile. Hence, it seems that particular transitions exert different levels of influence on migration, and more nuanced analysis is needed to establish the extent to which particular transitions shape migration in each country. In the next section, we present the results of event-history analyses, which aim to establish the relative importance of each life-course event in driving migration in Australia and Great Britain.

Migration and life-course events: What is the link?

Before reporting the results of the regression analysis, we briefly review the proportion of individuals in Australia and Great Britain who have experienced transitions of interest. Figure 5 reports the proportion of a population who have reached a particular status by age 35. It shows that educational attainment is the only difference between Australia and Great Britain, with 51 % of individuals attaining is higher education by age 35 in Great Britain, compared to 62 % in Australia. Thus, it is not the incidence of these transitions that underpins differences in each country’s migration age profiles.

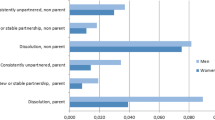

Figure 6 reports the odds-ratios of each life-course transition for all moves, which indicate the probability of moving associated with a particular transition. It shows that entry into higher education is the main driver of migration among young adults in both countries, increasing the likelihood of changing region of residence by a factor of 3.4 in Great Britain and 2.7 in Australia. In both countries, migration among young adults is also driven, albeit to a lesser extent, by entry into the labour market, particularly in Great Britain where it increases the likelihood of changing region by 3.1, compared to 1.5 in Australia. Further cross-national differences emerge when considering union formation, which raises the odds of moving by a factor of 3.1 in Great Britain, compared to 1.7 in Australia. While the association between marriage and migration is not statistically significant in Australia, it increases the chance of moving 1.5 times in Great Britain. The stronger connection between migration and union formation than marriage in both countries can be readily explained by cohabitation increasingly being the norm before marriage (Duvander 1999). A recent cross-national comparison of 16 industrialised nations showed that cohabitation led to marriage for 61 % of never-married women aged 15–44 (Heuveline and Timberlake 2004). Therefore, the transition from informal union to marriage does not normally entail a change of residence. Event-history analysis for males and females separately (“Appendix 2”) revealed minimal differences by sex.

Three factors appear to shape the concentration of migration within a narrow age range in Great Britain: (1) the strong association between migration and three life-course transitions, namely entry into higher education, entry into the labour market and union formation, (2) the alignment of the age at which two of the aforementioned transitions peak, namely higher education and labour force entry, and (3) the concentration of the transition with the strongest impact on migration, entry into higher education, within a very narrow age range. As previously shown in Fig. 3, Great Britain is characterised by a high concentration of migration activity in the early twenties and relatively low levels of mobility beyond 30, the age by which most individuals have transitioned to adult roles. In comparison, the protracted age profile of migration in Australia is triggered mainly by transitions dispersed across a much wider age range than in Great Britain, in particular entry into higher education.

We now turn to the influence of life-course events by distance moved. Figure 7 displays the odds-ratios associated with each transition separately for short- and long-distance migration. Figure 8 juxtaposes the age profiles of short- and long-distance migration to facilitate interpretation. Figure 7 shows that entry into higher education is the main trigger of short-distance migration in Australia, where it increases the probability of moving by a factor of 2.9. Other transitions either have a moderate impact (union formation has an odds-ratio of 1.6) or an impact that is not statistically significant (labour market entry, marriage and first childbirth). Over long distances, all life-course transitions have a low impact in Australia, with odds-ratios not exceeding 1.8. These results suggest that the prevalence of entry into higher education over short distances is associated with an early migration peak at age 21, whereas a weak association of all transitions with long-distance migration is reflected in a protracted age profile and peak at age 24.

Age profiles of migration over short and long distances. Note: Authors’ calculations based on one-year interval migration data reported by single-year age groups. Migration data was normalised to sum to unity and smoothed using kernel regression (Bernard and Bell 2015)

In Great Britain, union formation is the main trigger of short-distance moves, increasing the probability of moving by a factor of 3.6. Over long distances, mobility is strongly associated with economic transitions. Higher education entry and labour market entry raise the odds of moving by factors of 4.6 and 3.2 respectively. Higher employment-related mobility over long distances in Great Britain than in Australia is probably linked to the higher levels of mobility for educational purposes. These differences are likely to reflect variations between the two countries in the nature and prevalence of student migration (Bornholt et al. 2004; Holdsworth 2009; Mills 2006). Evidence suggests that graduates who left their region of origin to pursue further education are more likely to move long-distance to take up work in comparison to those who studied in their region of origin (Faggian et al. 2007), as the psychological and emotional costs of moving are relatively lower (DaVanzo 1983; Newbold 1997). In Great Britain, the influence of family-related transitions over long-distance mobility is much weaker than that of economic transitions, yet union formation increases the odds of moving by a factor of 2.3 and becoming a parent reduces the propensity to move by a factor of two. Based on these results, the strong concentration of long-distance moves in the early twenties appears to be driven by two factors. The first factor is the concentration of the main driver of migration, higher education entry, within a very narrow age range. Three quarters of British youth enter higher education by age 20. The second factor is the alignment of this transition with labour market entry, which peaks at a similar age. In comparison, the age structure of short-distance migration follows the late and protracted age profile of union formation, the transition with the strongest impact on migration.

In both countries, the age profile of short-distance moves is broadly similar to that for longer distances. Migration is consistently concentrated within a narrower age range in Great Britain, reflecting relatively brief life-course transitions, in particular higher education entry. This result is consistent with prior evidence that the age profile is largely scale-independent. For instance, Rogers and Castro (1981) and Plane and Heins (2003) found that the shape of the age profile of local mobility in the United States closely matched that of longer-distance migration. Bell and Muhidin (2009) reported a similar finding from comparing the age profiles of migration between minor administrative units in 19 countries with those of migration between major administrative units in the same countries. Nevertheless, it is clear from our results that subtle differences are to be found. For example, while long-distance migration peaks at a younger age in Great Britain (20) than in Australia (24), the opposite is true is for short-distance migration, which peaks at 21 in Australia and 24 in Great Britain. These differences appear to reflect variations in the mix of life-course transitions driving migration by distance moved. In particular, entry into higher education is the main trigger of short-distance migration in Australia whereas it is associated with long-distance migration in Great Britain. These differences are to some extent the result of variations in spatial frameworks as Australia and Great Britain are very different not only in geographic area but also in the size and distribution of their respective populations (Stillwell et al. 2000). Hence, moves between statistical divisions within states can take place over long distances in Australia whereas moves between local authorities in Great Britain entail shorter distances. Importantly, moves between Statistical Divisions in Australia capture only a small proportion of local residential mobility, which is generally thought to be driven by family-related transitions.

Socio-economic context: What Influence?

It is apparent that cross-national variations in migration age patterns are strongly shaped by differences in the influence of particular life-course transitions on mobility combined with variations in the age-structure of these transitions. This result is consistent with the proximate determinants framework proposed by Bernard et al. (2014b), according to which the structure and timing of the life course act as intermediaries between contextual factors and migration. The question that follows is how the broader socioeconomic context shapes the transition to adulthood, and hence mobility.

Australia and Great Britain have similar liberal welfare systems (Esping-Andersen 1990), where the market is the principal regulator of labour supply, and the state does relatively little to encourage or discourage participation in the labour force through social and fiscal policy (Mayer 2001). They also have similar value systems (Inglehart and Baker 2000), characterised by emphasis on self-expression (subjective well-being, tolerance, political activism, and quality of life concerns) over survival (economic and physical security), and their legal systems, which guide the ages at which adolescents are responsible for their own decisions, are all based on English common-law. However, despite broadly similar socio-economic structures, differences exist with respect to the age structure of entry into higher education and the strength of its association with migration. Because this transition is the main driver of migration among young adults in both countries, we explore how contextual factors may shape entry into higher education.

Geographic mobility has long been perceived as a critical part of the transition to higher education in the United Kingdom (Allatt 1993), and the majority of students move away from their parental home to pursue higher education (Christie 2007; Patiniotis and Holdsworth 2005), often over long distances. While moving for university is perceived as a rite of passage in the United Kingdom (Holdsworth 2006, 2009), educational markets are largely confined to individual states within Australia, and 60 % of students enrol in universities that are geographically convenient rather than moving from the parental home (Bornholt et al. 2004). As a result, entry into higher education is less strongly associated with migration overall, and where moves do take place they are likely to be over short distances.

This is partly the product of differences in geographic size and in the distribution of opportunities. Great Britain is much smaller in land area and has a more evenly distributed population than Australia. An individual in Australia moving between two cities to enter higher education or the labour market is more constrained to move further, because of the distance between major cities, than a corresponding individual in Britain. Nevertheless, higher education does drive mobility for young Australians, and more than a third of students who enrolled in their region of origin changed residence (Bornholt et al. 2004). The fact that Australians are less likely to move long-distance for educational motives may also explain the dispersion of entry into higher education across a wider age range. The absence of a cultural impetus to move away for university provides more possibilities for deferring entry into higher education in favour of other transitions such as labour market entry.

The institutionalised connections between school and work exert a strong influence on the transitions into and out of higher education (Mayer 2001). While in some countries the transition from school to work is organised around a standardised educational and training system with institutionalised pathways between educational and occupational systems (Heinz 1999), in other countries those linkages are less structured, with qualifications not closely relating to specific occupations, and requiring students to construct their own pathway (Mortimer and Krüger 2000). The spread of entry into higher education across a wider age range in Australia suggests that school and employment transitions are less closely coupled than in Great Britain. Data from our samples indicate that in Australia about 40 % of young adults are employed before entering higher education compared to only 17 % in Great Britain, which possibly contributes to the tightly scheduled educational transition among British young adults. Hence, the nature of the educational system and its linkages to the labour market in Great Britain appear to be conducive to a tightly scheduled sequencing of entry into higher education immediately preceding labour market entry. This in turn contributes to a concentration of migration activity among British youths within a narrow age range.

Conclusion

The persistent shape of the migration age profile has long suggested an intrinsic connection between life course and migration events as they typically occur at similar ages. We have also known that certain transitions are likely to trigger spatial mobility. What has been less clear until now is the relative significance of various life-course transitions on migration behaviour. Testing the connection between migration and multiple life-course transitions in a cross-national context has allowed us to tease out the extent of these linkages and the ways in which they vary in different contextual settings.

Using Australia and Great Britain as case studies, we have shown that variations in migration age patterns among young adults are shaped by differences between countries in the age structure of particular life-course transitions, and in the way these transitions combine. We have found that a strong association of migration with multiple life-course transitions results in a concentration of migration at young adult ages, whereas a weak association is reflected in protracted migration age patterns. When a single transition drives migration, its age distribution shapes that of migration but the alignment of multiple influential transitions amplifies the concentration of migration at young adult ages. In Great Britain, for example, the transitions to higher education, work and partnership all increase the probability of moving by a factor of 2 or more, so that three-quarters of long-distance moves occur between ages 17 and 35, whereas in Australia long-distance migration is more widely dispersed across ages, reflecting the limited influence of life-course transitions, all of which are characterised by low odds-ratios. The concentration of mobility in the early twenties in Great Britain is reinforced by the fact that the main drivers of long-distance migration, higher education and labour market entry, peak at similar early ages. In contrast, short-distance migration in Great Britain follows the late and protracted age profile of union formation, the main driver of moves over short distances. In Australia, on the other hand, most moves associated with the transition to higher education occur between regions within states, and it is this transition that dominates the age profile of short distance migration.

Taking a comparative approach underlines the utility of applying a Bongaarts-inspired framework to the study of migration. Separating the broader socio-economic context from the immediate drivers of migration has enabled us to isolate the pathways and the mechanisms by which these dynamics shape mobility. Thus, it appears that despite broadly similar socio-economic structures, pronounced differences exist between Australia and Great Britain in the mix of life-course transitions underpinning mobility among young adults. In particular, differences in the prevalence of student mobility and the displacements involved, coupled with variations in the age structures of higher education entry, seem to be key factors shaping differences in migration age patterns.

A promising direction for future work is application of the proximate determinants framework to a more heterogeneous group of countries, as the socio-economic context in which young adults’ lives are embedded varies widely among countries in different cultural settings and at different levels of human development. A second possibility is to track selected countries over time. The relationship between age and migration propensity is likely to evolve over time following patterns specific to different levels of socio-economic development (Warnes 1992b). Assessment of the extent to which long-term changes in the life course, such as the progressive extension of education to older ages and the delay in union and family formation, are associated with changes in the age structure of migration within individual countries would further enhance understanding of the role played by life-course transitions in shaping migration. While it is well established that life-course transitions evolve over time in response to changing economic circumstances, social norms, and institutional forces, the methodology adopted in this paper provides a framework to assess how these changes have combined to shape and reshape the age profile of migration.

Notes

For Australia, regions of residence are New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and other (ACT, Northern Territory and Tasmania). For Britain regions of residence are England, Wales and Scotland.

Remoteness is classified into four categories (major city, inner regional, outer regional and remote) based on the statistical local authority of residence.

References

Alderman, H., et al. (2001). Attrition in longitudinal household survey data. Demographic Research, 5(4), 79–124.

Allatt, P. (1993). Becoming privileged: The role of family processes. In I. Bates & G. Riseborough (Eds.), Youth and inequality. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Allison, P. D. (1982). Discrete-time methods for the analysis of event histories. Sociological Methodology, 13(1), 61–98.

Baccaïni, B., & Courgeau, D. (1996). The spatial mobility of two generations of young adults in Norway. International Journal of Population Geography, 2(4), 333–359.

Baxter, J., & Evans, A. (2013). Negotiating the life-course: Stability and change in life pathways. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bell, M., & Muhidin, S. (2009). Cross-national comparisons of internal migration. Human Development Research Paper 2009/30. New York: United Nations.

Bell, M., et al. (2002). Cross-national comparison of internal migration: Issues and measures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 165(3), 435–464.

Bell, M., Charles‐Edwards, E., Kupiszewska, D., Kupiszewski, M., Stillwell, J., & Zhu, Y. (2015). Internal migration data around the world: Assessing contemporary practice. Population, Space and Place, 21(1), 1–17.

Bernard, A., & Bell, M. (2015). Smoothing internal migration age profiles for comparative research. Demographic Research, 32(33), 915–948.

Bernard, A., Bell, M., & Charles-Edwards, E. (2014a). Improved measures for the cross-national comparison of age profiles of internal migration. Population Studies, 68(2), 179–195.

Bernard, A., Bell, M., & Charles-Edwards, E. (2014b). Life-course transitions and the age profile of internal migration. Population and Development Review, 40(2), 231–239.

Bogue, D. J., Liegel, G., & Kozloski, M. (2009). Immigration, internal migration, and local mobility in the US. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Bongaarts, J. (1978). A framework for analyzing the proximate determinants of fertility. Population and Development Review, 4(1), 105–132.

Borjas, G. J. (1994). The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature, 32(4), 1667–1717.

Bornholt, L., Gientzotis, J., & Cooney, G. (2004). Understanding choice behaviours: Pathways from school to university with changing aspirations and opportunities. Social Psychology of Education, 7(2), 211–228.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., & Jones, B. S. (2004). Event history modeling: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bracken, I., & Bates, J. (1983). Analysis of gross migration profiles in England and Wales: Some developments in classification. Environment and Planning A, 15(3), 343–355.

Buchmann, M. C., & Kriesi, I. (2011). Transition to adulthood in Europe. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 481–503.

Buck, N. (2000). Using panel surveys to study migration and residential mobility. In D. Rose (Ed.), Researching social and economic change. Routledge: London.

Christie, H. (2007). Higher education and spatial (im) mobility: Nontraditional students and living at home. Environment and Planning A, 39(10), 2445.

Clark, W. A., & Huang, Y. (2003). The life course and residential mobility in British housing markets. Environment and Planning A, 35(2), 323–340.

Courgeau, D. (1985). Interaction between spatial mobility, family and career life-cycle: A French survey. European Sociological Review, 1(2), 139–162.

Corcoran, J., Faggian, A., & McCann, P. (2010). Human capital in remote and rural Australia: The role of graduate migration. Growth and Change, 41(2), 192–220.

DaVanzo, J. (1983). Repeat migration in the United States: Who moves back and who moves on? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 65(4), 552–559.

Dotti, N. F., Fratesi, U., Lenzi, C., & Percoco, M. (2013). Local labour markets and the interregional mobility of Italian university students. Spatial Economic Analysis, 8(4), 443–468.

Duvander, A.-Z. E. (1999). The transition from cohabitation to marriage a longitudinal study of the propensity to Marry in Sweden in the Early 1990s. Journal of Family Issues, 20(5), 698–717.

Easterlin, R. A., Wachter, M. L., & Wachter, S. M. (1978). Demographic influences on economic stability: The United States experience. Population and development review, 4(1), 1–22.

Eicker, F. (1967). Limit theorems for regressions with unequal and dependent errors. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (pp. 59–82). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism (Vol. 6). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Faggian, A., Comunian, R., Jewell, S., & Kelly, U. (2013). Bohemian graduates in the UK: Disciplines and location determinants of creative careers. Regional Studies, 47(2), 183–200.

Faggian, A., McCann, P., & Sheppard, S. (2007). Human capital, higher education and graduate migration: An analysis of Scottish and Welsh students. Urban Studies, 44(13), 2511–2528.

Fitzgerald, J., Gottschalk, P., & Moffitt, R. A. (1998). An analysis of sample attrition in panel data: The Michigan Panel study of income dynamics. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Flowerdew, R., & Al-Hamad, A. (2004). The relationship between marriage, divorce and migration in a British data set. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(2), 339–351.

Gauthier, A. H. (2007). Becoming a young adult: An international perspective on the transitions to adulthood. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 23(3), 217–223.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Groves, R. M., & Couper, M. P. (1998). Nonresponse in household interview surveys. New York: Wiley.

Grundy, E. (1992). ‘The household dimension in migration research. In A. G. Champion & T. Fielding (Eds.), Migration processes and patterns (Vol. 1, pp. 165–174). London: Research Progress and Prospects, Belhaven.

Gujarati, D., & Porter, D. C. (2009). Basic econometrics. Singapore: McGraw-Hill.

Haapanen, M., & Tervo, H. (2009). Return and onward migration of highly educated: Evidence from residence spells of Finnish graduates. Jyväskylä: School of Business and Economics, University of Jyväskylä.

Heinz, W. R. (1999). From education to work: Cross national perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heuveline, P., & Timberlake, J. M. (2004). The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(5), 1214–1230.

Hoare, T. (1991). University competition, student migration and regional economic differentials in the United Kingdom. Higher Education, 22(4), 351–370.

Holdsworth, C. (2006). ‘Don’t you think you’re missing out, living at home?’ Student experiences and residential transitions. The Sociological Review, 54(3), 495–519.

Holdsworth, C. (2009). Going away to uni’: Mobility, modernity, and independence of English higher education students. Environment and Planning. A, 41(8), 1849.

Huber, P.J (1967), ‘The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (Vol. 1, 221–233) Berkeley: University of California Press.

Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 19–51.

Ishikawa, Y. (2001). Migration turnarounds and schedule changes in Japan, Sweden and Canada. Review of Urban & Regional Development Studies, 13(1), 20–33.

James, R., Baldwin, G., & McInnis, C. (1999). Which University? The factors influencing the choices of prospective undergraduates. Canberra: Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne.

Jeon, Y., & Shields, M. P. (2005). The Easterlin hypothesis in the recent experience of higher-income OECD countries: A panel-data approach. Journal of Population Economics, 18(1), 1–13.

Kawabe, H. (1990). Migration rates by age group and migration patterns: Application of Rogers’ migration schedule model to Japan, the Republic of Korea, and Thailand. Tokyo: Institute of Developing Economies.

Kulu, H. (2008). Fertility and spatial mobility in the life course: Evidence from Austria. Environment and Planning A, 40(3), 632–652.

Lindgren, U. (2003). Who is the counter-urban mover? Evidence from the Swedish urban system. International Journal of Population Geography, 9(5), 399–418.

Long, L. (1988). Migration and residential mobility in the United States The Population of the United States in the 1980s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2005). Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 989–1002.

Mayer, K. U. (2001). The paradox of global social change and national path dependencies: Life course patterns in advanced societies. In A. E. Woodward & M. Kohli (Eds.), Inclusions and exclusions in European societies (pp. 89–110). London: Routledge.

McCann, P., & Sheppard, S. (2001). Public investment and regional labour markets: the role of UK higher education. In Public investment and regional economic development: essays in honour of Moss Madden (pp. 135–53).

Mills, J. (2006). Student residential mobility in Australia: An expiration of higher education-related migration. St Lucia: The University of Queensland.

Milne, W. J. (1993). Macroeconomic influences on migration. Regional Studies, 27(4), 365–373.

Modell, J., Furstenberg, F., & Hershberg, T. (1976). Social change and transitions to adulthood in historical perspective. Journal of Family History, 1(1), 7–32.

Mortimer, J. T., & Krüger, H. (2000). Pathways from school to work in Germany and the United States. In Handbook of the Sociology of Education (pp. 475–497).

Mulder, C. H. (1993). Migration dynamics: A life course approach. Amsterdam: Thesis Publisher.

Mulder, C. H., & Clark, W. (2002). Leaving home for college and gaining independence. Environment and Planning A, 34(6), 981–1000.

Mulder, C. H., Clark, W. A. V., & Wagner, M. (2002). A comparative analysis of leaving home in the United States, the Netherlands and West Germany. Demographic Research, 7, 565–592.

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (1993). Migration and marriage in the life course: a method for studying synchronized events. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 9(1), 55–76.

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (1998). First-time home-ownership in the family life course: A West German–Dutch comparison. Urban Studies, 35(4), 687–713.

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (2001). The connections between family formation and first-time home ownership in the context of West Germany and the Netherlands. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 17(2), 137–164.

Newbold, K. B. (1997). Primary, return and onward migration in the US and Canada: Is there a difference? Papers in Regional Science, 76(2), 175–198.

Niedomysl, T. (2011). How migration motives change over migration distance: Evidence on variation across socio-economic and demographic groups. Regional Studies, 45(6), 843–855.

Pandit, K. (1997). Demographic cycle effects on migration timing and the delayed mobility phenomenon. Geographical Analysis, 29(3), 187–199.

Patiniotis, J., & Holdsworth, C. (2005). ‘Seize that chance!’ Leaving home and transitions to higher education. Journal of Youth Studies, 8(1), 81–95.

Plane, D. A., & Heins, F. (2003). Age articulation of US inter-metropolitan migration flows. The Annals of Regional Science, 37(1), 107–130.

Rabe, B., & Taylor, M. (2010). Residential mobility, quality of neighbourhood and life course events. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 173(3), 531–555.

Reed, H. E., Andrzejewski, C. S., & White, M. J. (2010). Men’s and women’s migration in coastal Ghana: An event history analysis. Demographic Research, 22(25), 771–812.

Rindfuss, R. R. (1991). The young adult years: Diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography, 28(4), 493–512.

Rogers, A., & Castro, L. J. (1981), Model migration schedules. In Research Report RR-81-30. Laxenburg, Austria: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Rothman, S. (2009). Estimating attrition bias in the year 9 cohorts of the longitudinal surveys of australian youth. LSAY Technical Reports (Technical Report No 48).

Sander, N., & Bell, M. (2014). Migration and retirement in the life-course: An event-history approach. Journal of Population Research, 31(1), 1–27.

Shanahan, M. J. (2000). Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual review of sociology, 26, 667–692.

Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The costs and returns of human migration. The Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 80–93.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 267–306.

Stillwell, J., et al. (2000). A comparison of net migration flows and migration effectiveness in Australia and Britain: Part 1, total migration patterns. Journal of Population Research, 17(1), 17–38.

Uhrig, S. C. (2008) The nature and causes of attrition in the British Household Panel Study. No. 2008-05. ISER Working Paper Series, 2008.

Venhorst, V. A., Van Dijk, J., & Van Wissen, L. (2011). An analysis of trends in spatial mobility of Dutch graduates. Spatial Economic Analysis, 6(1), 57–82.

Warnes, A. M. (1992a). Migration and the life course. In T. Champion & T. Fielding (Eds.), Migration processes and patterns: Research progress and prospects (Vol. 1, pp. 175–187). London: Belhaven Press.

Warnes, A. M. (1992b). Age-related variation and temporal change in elderly migration. In A. Rogers (Ed.), Elderly migration and population redistribution (pp. 35–55). London: Belhaven Press.

Waston, N., & Wooden, M. (2004). Sample attrition in the HILDA survey. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 7(2), 293–308.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2002). Assessing the quality of the HILDA survey wave 1 data. HILDA Project Technical Paper Series (No. 4/02) Melbourne: The University of Melbourne.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2009). Identifying factors affecting longitudinal survey response. Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, 1, 157–182.

Wrigley, N., et al. (1996). Analysing, modelling and resolving the ecological fallacy. In P. Longley & M. Batty (Eds.), Spatial analysis, modelling in a GIS Environment (pp. 23–40). Cambridge: GeoInformation International.

Yamaguchi, K. (1991). Event history analysis (Vol. 28). Newbury Park: Sage.

Yi, Z., et al. (1994). ‘Leaving the parental home: Census-based estimates for China, Japan, South Korea, United States, France, and Sweden. Population Studies, 48(1), 65–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Fig. 9.

Age profiles of migration by sex. Note: Authors’ calculations based on 1-year interval migration data reported by single-year age groups. Migration data was normalised to sum to unity and smoothed using kernel regression (Bernard and Bell 2015). The x-axis represents single years of age and the y-axis represents migration intensities

Appendix 2

See Table 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bernard, A., Bell, M. & Charles-Edwards, E. Internal migration age patterns and the transition to adulthood: Australia and Great Britain compared. J Pop Research 33, 123–146 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-016-9157-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-016-9157-0